Abstract

Among the many pathophysiologic consequences of traumatic brain injury are changes in catecholamines, including dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. In the context of TBI, dopamine is the one most extensively studied, though some research exploring epinephrine and norepinephrine have also been published. The purpose of this review is to summarize the evidence surrounding use of drugs that target the catecholaminergic system on pathophysiological and functional outcomes of TBI using published evidence from pre-clinical and clinical brain injury studies. Evidence of the effects of specific drugs that target catecholamines as agonists or antagonists will be discussed. Taken together, available evidence suggests that therapies targeting the catecholaminergic system may attenuate functional deficits after TBI. Notably, it is fairly common for TBI patients to be treated with catecholamine agonists for either physiological symptoms of TBI (e.g. altered cerebral perfusion pressures) or a co-occuring condition (e.g. shock), or cognitive symptoms (e.g. attentional and arousal deficits). Previous clinical trials are limited by methodological limitations, failure to replicate findings, challenges translating therapies to clinical practice, the complexity or lack of specificity of catecholamine receptors, as well as potentially counfounding effects of personal and genetic factors. Overall, there is a need for additional research evidence, along with a need for systematic dissemination of important study details and results as outlined in the common data elements published by the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke. Ultimately, a better understanding of catecholamines in the context of TBI may lead to therapeutic advancements.

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, catecholamine, dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine, therapy

1. Introduction

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) is a significant public health problem in the United States. In 2010 alone, an estimated 2.5 million TBI cases presented for treatment and it is likely that many more cases went unreported (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). The mechanism of injury varies greatly and includes motor vehicle accidents, falls, and gunshot wounds, to name a few; the unpredicatable nature of TBI complicates the establishment of preventative measures. Thus it is imperative to identify effective treatments that prevent secondary injury (NIH, 1998). While TBI has become a largely survivable condition, an estimated 50% of TBI survivors live with long-term functional deficits (Kraus et al., 2005; Thurman et al., 1999). Post-TBI, deficits are common in several functional domains, including: learning (e.g. information processing), memory (short- and long-term), executive function (e.g. problem solving; impulse control) and/or other areas (e.g. language; attention; agitation; mood/affect) (Arciniegas et al., 2000; Dyer et al., 2006; Oddy et al., 1985; Sun and Feng, 2013). TBI survivors have elevated rates of mental health symptoms including: depression (Jorge et al., 2004; Moldover et al., 2004; Seel et al., 2003), agitation (Bogner et al., 2015), impulsivity, and verbally aggressive behavior (Dyer et al., 2006). Cognitive, behavioral, and mood symptoms are distressing and challenging to cope with. These symptoms may also impair the survivor’s ability to return to pre-injury roles (e.g. work, family, social) and contribute to caregiver burden (Binder, 1986).

Though changes in behavior may occur without measurable changes in physiology, the aforementioned TBI long-term deficits are often accompanied by changes in key brain structures known to control the functions affected, including the hippocampus, thalamus, and frontal cortex (Bramlett and Dietrich, 2002; Lifshitz et al., 2007; Vertes, 2006). Beyond the brain structures themselves, there are post-TBI alterations in brain cell communication via changes in underlying neurotransmitter systems; pathologic changes in these systems represent potential therapeutic targets for novel TBI therapies. The focus of this invited review is limited to one family of neurotransmitters: the catecholaminergic system. Catacholamines neurotransmitters fall into the monoamine family, which are derived from aromatic amino acids (e.g. L-tyrosine) and have a characteristic structure comprised of an amino group connected to a ring by a short double carbon chain. Catecholamines bind to adrenergic receptors (e.g. α; β), which are found throughout the body. This system is known to be altered following TBI; an acute catecholamine surge can be detected in the form of increased plasma levels (Hamill et al., 1987; Tran et al., 2008; Woolf et al., 1987). Moreover, there are commercially available drugs that target these neurotransmitters either directly or indirectly. In fact, some catecholamines (e.g. norepinephrine; dopamine) are commonly administered vasopressors used to raise cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) and mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) after TBI; use of catecholamines has been associated with clinically-relevant increases in CPPs that varied depending on which catecholamine was given in studies of pediatric- (Di Gennaro et al., 2011) and adult-(Sookplung et al., 2011) TBI. There is also clinical evidence associating use of norepinephrine- and dopamine-agonist stimulants with less severe agitation after TBI (Bogner et al., 2015). Despite the association between catecholamine therapy outcomes, relatively little causal evidence exists and what has been published is largely limited to pre-clinical trials. Moreover, there is no consensus regarding how to best exploit catecholamine therapies to promote TBI recovery given the diversity of TBI patients and complexities of clinical care.

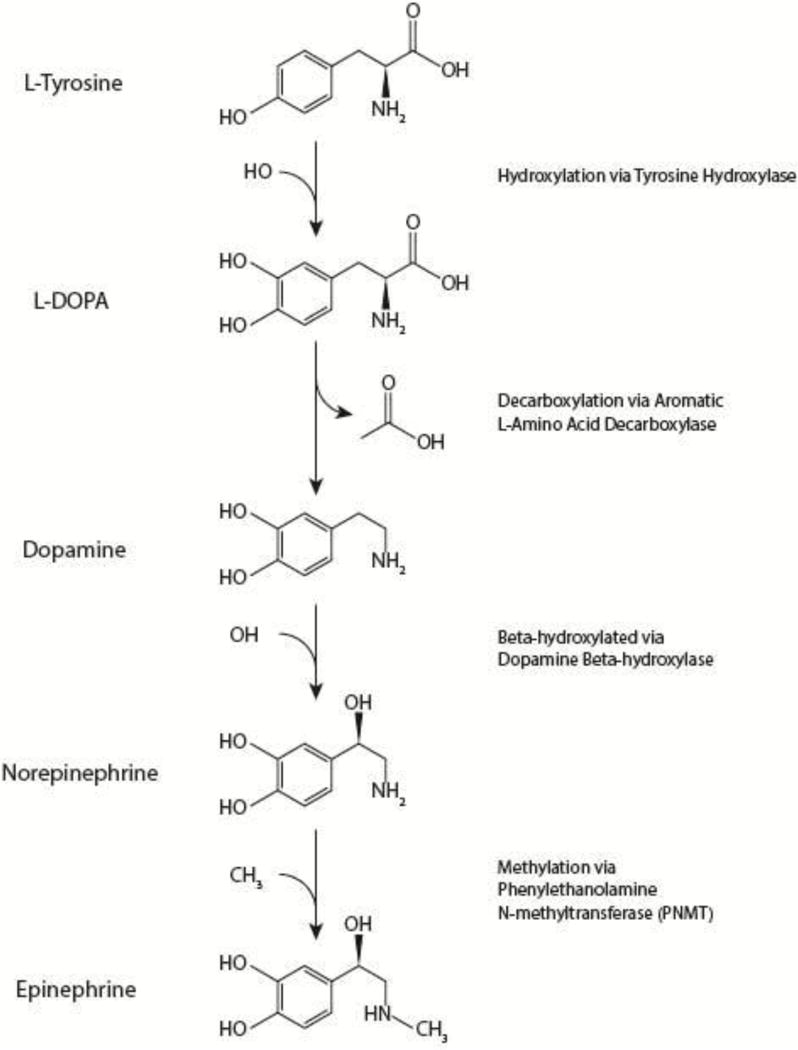

The purpose of this review is to synopsize the evidence regarding therapeutic applications of catecholamines in the context of pre-clinical and clinical TBI. The evidence cited will come from pre-clinical research, which represents the bulk of the available data; however, when available, published clinical evidence will be incorporated. In this reveiw, three main catecholamines will be discussed in detail: dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. In the context of TBI, dopamine is the best studied catecholamine and will thus be emphasized in this review; epinephrine and norepinephrine will be discussed in less detail due to the relative dearth of published evidence. Moreover, other less common catecholamines were excluded from this review due to insufficient evidence specific to TBI. It is also notable that the 3 neurotransmitters emphasized in this review are produced in a sequential pathway starting with L-tyrosine which is processed into L-dihydroxyphenyalanine (L-DOPA), dopamine, norepinephrine, and eventually epinephrine (see Figure 1). For each catecholamine discussed, a brief overview will be provided with attention given to evidence specific to the changes reported in the context of TBI. For each catecholamine, broad classes of drugs (e.g. agonist; antagonist) will be discussed, emphasizing evidence specific to therapeutic effects reported in the context of TBI and similar conditions.

Figure 1. Production of Dopamine (DA), Norepinephrine (NE), and Epinephrine (EPI).

The amino acid L-tyrosine is hydroxylated to form L-dihydroxyphenyalanine (L-DOPA), which is decarboxylated into DA, which goes on to be β-hydroxylated into NE, and finally methylated to form EPI.

2. Dopamine

2.1 Overview

Of the catecholamines found within the CNS, dopamine (DA) is most common (Cosentino and Marino, 2013; Vallone et al., 2000), Two brain regions are primarily responsible for DA synthesis, the substantia nigra pars compacta and the ventral tegmental area (Dalley and Roiser, 2012; Nieoullon, 2002; Seamans and Yang, 2004; Vallone et al., 2000). Several detailed descriptions of dopamine synthesis have been published previously and a summary is provided in Figure 1 (Elsworth and Roth, 1997; Fernstrom, 1983; Icard-Liepkalns et al., 1993; Milner and Wurtman, 1986; Misu and Goshima, 1993). Dopamine has several receptors to which it binds (e.g. D1, D2, D3, D4). Some drugs bind selectively or preferentially to one or more receptor subtype, as will be discussed in section 2.2 and 2.3.

In addition to receptors, the DAergic system includes several notable structures throughout the CNS. The ascending DAergic pathways is comprised of two parts: 1) the nigrostriatal pathway and 2) the mesocorticolimbic pathway (Alexander and Crutcher, 1990; Graybiel, 1990; Haber et al., 2006, 2000), both pathways are important for various functional outcomes known to be relevant to TBI symptomatology. The nigrostriatal system has been implicated in spatial learning/memory. Lesions to the nigrostriatal pathway are associated with alterations in behavioral strategy selection when faced with spatial navigation challenges such as the Morris water maze (Mura and Feldon, 2003). Moreover, the nigrostriatal system also has a role in reward processing (Wickens et al., 2007). Some of the cognitive symptoms associated with TBI, that also occur in Parkinson’s Disease (PD), have been attributed to the characteristic nigrostrial system changes underlying PD pathology (Ridley et al., 2006; Tamaru, 1997). The mesocorticolimbic pathway plays an important role in memory consolidation (Cools et al., 1993; Ploeger et al., 1994, 1991; Setlow and McGaugh, 1998), motivation (Baldo and Kelley, 2007; Mitchell and Gratton, 1994; Salamone, 1994), and addiction (Berridge, 2006; Di Chiara and Bassareo, 2007; Ikemoto, 2007; Salamone et al., 2005; Sutton and Beninger, 1999). This system has been implicated in neuropsychiatric disorders and conditions more boardly related to stress and mood (Abi-Dargham and Moore, 2003; Sonuga-Barke, 2005; Tidey and Miczek, 1996; Viggiano et al., 2003). In the context of TBI, less is known about the role of the mesocorticolimbic system. However, evidence from another neurocritical care disorder, stroke, has found damage to this region is associated with fatigue (Tang et al., 2013, 2010), a symptom experienced by an estimated 80% of TBI survivors (Cantor et al., 2013).

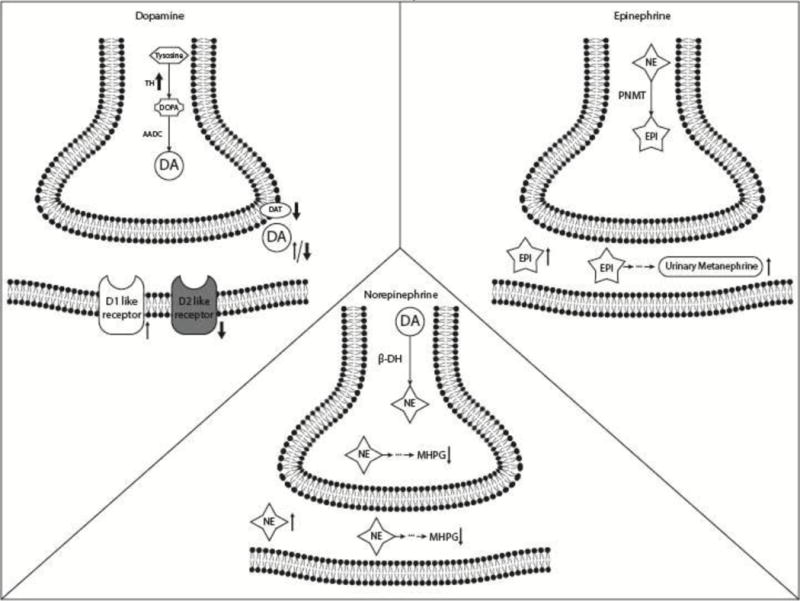

There are also several published changes to the DAergic system after TBI. Acutely, DA levels are elevated in several parts of the brain, whereas in the long-term, DA levels are depressed (Huger and Patrick, 1979; Kline et al., 2004; McIntosh et al., 1994). Changes in gray and white matter comprising the DAergic system have been reported after TBI (Bramlett and Dietrich, 2002; Hutson et al., 2011; J. M. Meythaler et al., 2001; Reeves et al., 2007). Other pathophysiological changes in the dopaminergic (DAergic) system after TBI include altered DA: production (Kobori et al., 2006), activity (Kobori et al., 2006; Shin et al., 2012), transmission (Henry et al., 1997; Huger and Patrick, 1979; Kline et al., 2004; McIntosh et al., 1994), and metabolism (Massucci et al., 2004). Metabolism of DA in microglial cells is altered within the first day of TBI and persists out to two weeks (Redell and Dash, 2007). Longer-term evidence of disrupted DA metabolism after TBI is suggested by chronic changes in DA transporter (DAT) expression (Wagner et al., 2009, 2005b); DAT binding was reduced 4–5 months following a TBI (Donnemiller et al., 2000; Wagner et al., 2007), without overt physiological damage (See Figure 2). Further evidence supporting the role of DA in TBI pathology surrounds the neuroprotective events occurring within certain brain regions (e.g. hippocampus; thalamus) which require interaction between DA and glutamate (Centonze et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2007; Granado et al., 2008; O’Carroll et al., 2006). The known effects of TBI on the DAergic system have led to trials of drugs targeting DA as agonists, antagonists, or via indirect mechanisms (as described in sections 2.2, 2.3 and 2.4). Though translation is limited, the promise of DAergic therapies was included in The Neurotrauma Foundation (NTF) report covering the foundation’s therapeutic recommendations for TBI (Warden et al., 2006)

Figure 2. Key changes to catecholamine systems after TBI.

This figure highlights several notable changes within the three major catecholamine neurotransmitters discussed in this review: DA, NE, and EPI. In the figure, up arrow denotes an increase and down arrow denotes a decrease; bold arrows denote chronic changes and non-bold arrows denote acute changes. Notable changes to the DAergic system after TBI include acute spike in DA, chronic depletion of DA, acute increase in D1-like receptors, chronic decreases in D2-like receptors, chronic increase in tyrosine hydroxylatse (TH), and chronic decrease in dopamine trasporter (DAT) function. Changes to the NE system after TBI include acute spikes in NE levels and decreased turnover of NE to 3-methoxy-4 hydroxyphenylglycol (MHPG). Post-TBI changes to the epinephrine system include an acute spike in epinephrine levels and decreased excretion as urinary metanephrine.

2.2 Dopamine Agonists

To-date, a number of preclinical TBI studies have been conducted testing DA agonists, most of which began therapy within a day of TBI and continued chronically. Based on the available evidence, DAergic agnonists have shown promise for the treatment of TBI both acutely and into the long-term (Bales et al., 2009; Gualtieri and Evans, 1988; Kaelin et al., 1996; Zweckberger et al., 2010), a few key examples of which are discussed below, sorted by specific agonist drug. In addition to the agonists described in 2.2.1, 2.2.2, and 2.2.3, dopamine is sometimes given in the form of Inotropin therapy, which acts via alpha-1 and beta-1 receptors. Inotropin therapy is known to have drug-drug interactions with several classes of drugs including some that may be administered as part of TBI management or for treatment of a comorbid condition (e.g. halogenated hydrocarbon anesthetics; monoamine oxidase inhibtitors; phenytoin; triclyclic antidepressants); thus, dopamine is typically agonized using one of the drugs listed below instead.

2.2.1 Bromocriptine

Bromocriptine is an agonist specific to the D2 receptor, which is known to protect neurons in the cortex from the toxic effects of glutamate (Kihara et al., 2002). Bromocriptine treatment following experimental TBI enhanced working and spatial memory; these changes were associated with reduced oxidative damage (Kline et al., 2004, 2002). The Neurotrauma Foundation (NTF) recommendations include bromocriptine, which has also been found to be positively associated with favorable outcomes related to executive functioning (Warden et al., 2006). In a placebo-controlled crossover study of 24 TBI survivors, bromocriptine was found to improve executive function and duel-task performance, though other assessments of cognitive function showed no effect (McDowell et al., 1998). A recent clinical study used functional MRI (fMRI) verbal working memory task to compare TBI survivors to health controls 1 month after initial injury testing the effects of bromocriptine on verbal working memory performance; though healthy controls had better memory performance after bromocriptine administration, responsivity to this DAergic drug was not evident in TBI survivors (McAllister et al., 2011).

2.2.2 Amantadine

Amantadine is another agonist of the DAergic system (Gianutsos et al., 1985; Von Voigtlander and Moore, 1971), which, like bromocriptine, was recommended by the NTF (Warden et al., 2006). In addition to its role as a DA agonist, amantadine is known to antagonize N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) type glutamate receptors; this non-specific nature of amantadine complicates studying the effects and underlying mechanism of this drug in the context of brain injury (Kornhuber et al., 1994). Amantadine has been well studied in the context of both pre-clinical and clinical TBI where it has been found to support cognitive function (Stelmaschuk et al., 2015). In the context of pre-clinical TBI modeled using controlled cortical impact (CCI), amantadine has been found to ameliorate post-CCI Morris water maze deficits; yet, it did not significantly improve motor deficits with the injury parameters and treatment regimens trialed (Dixon et al., 1999). Following fluid percussion injury (FPI) in rats, a higher dose of amantadine treatment was associated with higher survival rates of CA2 and CA3 pyramidal neurons, along with beneficial effects on cognitive testing (Wang et al., 2013). Another FPI study found that after amantadine therapy there was both attenuation of DA-release deficits and subsequent functional deficits (Huang et al., 2014). In clinical trials, amantadine is associated with beneficial outcomes on measures of agitation (Chandler et al., 1988) as well as overall rate of functional recovery assessed using the Disablity Rating Scale (Giacino et al., 2012). In a study of severe TBI patients amantadine treatment was associated with better outcomes on Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and Glascow Outcomes Scale (GOS), along with lower mortality when compared to standard-of-care controls (Saniova et al., 2004). Though overall amantadine seems to be a promising therapy (Spritzer et al., 2015; Stelmaschuk et al., 2015), some studies have failed to find significant effects on TBI outcomes including irritability (Hammond et al., 2015).

2.2.3 Dopamine Agonists Used in Parkinson’s Disease

Other agonists of the DAergic pathway, such as ropinirole and pramipexole, have demonstrated protective effects in the context of PD (Schapira, 2009), indicating possible therapeutic applications in TBI. These agonists act by binding to DA receptor and are implicated in the prevention of oxidative stress (Nair and Sealfon, 2003). In the context of TBI, pramipexole has been used to treat certain symptoms of sleep disorders, specifically sleep-related limb movements (Castriotta and Murthy, 2011). In addition to acting on DA several receptor subtypes (D2, D3, and D4) with preferential binding to D3 (Piercey, 1998), pramipexole may have additional effects on neurotrophic factors (Du et al., 2005). One study of pramipexole found treatment reduced death of nigrostriatal neurons following ischemia (Hall et al., 1996). In a pediatric TBI study, pamipexole resulted in faster rates of change on the Coma/Near Coma Scale, Western NeuroSensory Stimulation Profile, and Disability Rating Scale (Patrick et al., 2006).

2.2.4 Stimulants

Methylphenidate (MPD) is associated with rapid processing and improved attention (Warden et al., 2006) and has been trialed as a TBI therapeutic with conflicting results (Mooney and Haas, 1993; Speech et al., 1993). Specifically, MPD inhibits DAT, and taking MPD has been associated with improved memory and attention when administered in the long-term after brain injury (Gualtieri and Evans, 1988; Lee et al., 2005; Pavlovskaya et al., 2007). Additional evidence suggests that administration of MPD is also associated with favorable cognitive outcomes (Kaelin et al., 1996; Plenger et al., 1996; Whyte et al., 2004). In the context of cortical ablation and impact, MPD treatment ameliorates deficits in cognitive function observed after experimental brain injury induced using CCI or ablation (Kline et al., 2000, 1994). Spikes in DA observed following MPD administration are associated with better cognitive outcomes after experimental TBI (Schiffer et al., 2006; Volkow et al., 2004). In TBI clinical trials, MPD has demonstrated therapeutic benefits(Volz, 2008). Both pre-clinical and clinical studies suggest that the drug works via DAT blockade (Volkow et al., 2002a, 2002b, 1998).

Amphetamine (AMPH) has many cellular effects including stimulating DA release and blocking reuptake (Kahlig and Galli, 2003), leading to elevated extracellular DA and subsequently prolonged striatal DAergic signaling (Calipari and Ferris, 2013). In addition, DA removes unwanted cellular debris (e.g. free fatty acids; lactate) from the cortex and hippocampus (Dhillon et al., 1998). After TBI, AMPH is known to be involved in post-injury plasticity and synaptogenesis (Goldstein, 2003; Ramic et al., 2006); these reported benefits may be related to the induction of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Griesbach et al., 2008). It is also known that AMPH leads to decreased utilization of cerebral glucose after experimental TBI (Queen et al., 1997). Recovery after pre-clinical TBI is accelerated with AMPH treatment (Barbay and Nudo, 2009; Chudasama et al., 2005; Dhillon et al., 1998; Hovda et al., 1989; M’Harzi et al., 1988). Unfortunately, translating AMPH to clinical care is difficult because it impacts other monoamines (Fleckenstein et al., 2007); moreover it is well- established that the drug has the potential for abuse and dependence. Further complicating the use of AMPH is the fact that D2 agonists are commonly used to treat TBI patients yet they may counteract the effects of AMPH (Feeney et al., 1982). Methamphetamine, a stimulant which binds has also been evaluated in experimental TBI with mixed results (Rau et al., 2012; Shen et al., 2011).

2.2.5 Reuptake Inhibitors

Further evidence that the DAergic system contributes to post-TBI inflammation comes from drug trials demonstrating decreased inflammation can be achieved by targeting DA pathways; for example, the selective norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor buproprion (Stahl et al., 2004), which is used traditionally to treat depression, has also been found to have anti-inflammatory effects following brain injury (Brustolim et al., 2006). However, there remains some concern that there is a role for inflammatory cells in post-TBI neuroprotection which may complicate treatment with anti-inflammatory agents (Ekdahl et al., 2009; Kriz, 2006). In the context of PD, degeneration of DA neurons may be related to elevated cytokines (e.g. TNF, IL-1beta, IL-6, and TGF-alpha) and decreased neurotrophins (e.g. BDNF) which contributes to inflammation (Färber and Kettenmann, 2005; Nagatsu et al., 2000). Similarly, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been trialed in the context of TBI. In a mouse model, fluoxetine has been found to promote neurogenesis and moderate epigenetic factors, though no effects on functional outcomes were detected (Wang et al., 2011). A rat model did find beneficial effects on functional outcomes of TBI with chronic SSRI treatment (Mahesh et al., 2010). In clinical studies, the SSRI sertraline was trialed but no beneficial effects were detected (Baños et al., 2010; J. Meythaler et al., 2001); another clinical study showed little improvement when sertraline was compared to placebo (Ashman et al., 2009). Conversely, one study showed transient beneficial effects of sertraline on depression; though significant group differences were seen at 3 months, the trend did not persist over time when assessed out to 1 year (Novack et al., 2009). Taken together, existing evidence suggests that DA may moderate inflammatory processes within the brain, though there is a need for additional research.

2.3 Dopamine Antagonists

Interestingly, there are also reported benefits associated with administration of DA antagonists. For example, beneficial effects have been published in several neurological conditions including models of brain lesion, ischemia, and excitotoxicity (Armentero et al., 2002; Okada et al., 2005; Yamamoto et al., 1994; Zou et al., 2005). Following concussive injury in mice, acute treatment (15 min) with selective antagonists of the D2 receptor lead to beneficial effects; moreover, an additive effect of treatment was noted when D1 and D2 receptors were antagonized in combination (Tang et al., 1997). Compared to DA agonists, the therapeutic effects of DA antagonists after brain injury remain less clear, though acute administration may have anti-excitoxicity effects. Overall, there is a need for future research aimed at testing various DA antagonists.

Some commonly prescribed antipsychotics antagonize dopamine receptors, including haloperidol (Moe et al., 2011) and risperidone (Janssen et al., 1988). Both are used in TBI patients, often not for treatment of psychosis or agitation, but rather for their sedative effects (Stanislav, 1997). Some studies using D2 receptor antagonists have found treatment was associated with poorer outcomes, as was true in some trials of haloperidol and risperidone (Hoffman et al., 2008). In a recent case study, when risperidone was perscribed to a 69 year old male who sustained a TBI 5 months prior and had developed symptoms of aggression, development of Parkinson-like symptoms were reported (Kang and Kim, 2013). In a trial of haloperidol in experimental TBI, delayed motor recovery was observed (Feeney et al., 1982; Goldstein and Bullman, 2002). It is also worth acknowledging that TBI survivors prescribed amphetamine (AMPH) may take haloperidol to counteract the adverse effects of AMPH therapy (Feeney et al., 1982).

3. Norepinephrine

3.1 Overview

Norepinephrine (NE), also called noradrenaline, is the second catecholamine to be discussed in detail in this review. NE, like epinephrine (see Section 4), pays an important role in the fight or flight response. Indeed, both neurotransmitters bind to adrenergic receptors and share other important similarities; however, NE is better-studied in the context of TBI. NE is believed to play a role in TBI recovery and the neurobehavioral symptoms experienced by survivors (Mahesh et al., 2010). One study in cats found spikes in NE following TBI (Rosner et al., 1984) as depicted in Figure 2. Clinically, TBI survivors often receive NE therapy for its vasopressive effects and one study found that NE levels in the CSF and plasma were elevated in TBI survivors treated with NE as well as some individuals who did not receive therapeutic NE; interestingly, the spike in plasma levels was independent of whether or not the blood-brain-barrier remained intact (Mautes et al., 2001). In this study, no evidence of toxicity from NE therapy was reported, nor were there correlations between GCS and NE levels. Pre-clinical evidence suggests lower turnover of NE after experimental TBI in rats, measured as the ratio of 3-methoxy-4 hydroxyphenylglycol (MHPG) to NE (see Figure 2); these changes in MHPG were reported at the injury site as well as in the cerebral cortex both rostral and caudal to the site of impact (Levin et al., 1995). A later study used high-performance liquid chromatography to determine the ratio of MHPG:NE and found that in most brain regions, levels restored to that of sham by 2 hours after experimental TBI (Dunn-Meynell et al., 1998).

3.2 Agonists

Catecholamine agonists are often used after TBI to maintain CPP; one pediatric study found NE was more commonly administered to older pediatric patients (Di Gennaro et al., 2011). Another study examined 13 severe TBI patients, over half (n=8) of whom had symptoms leading to the prescription of NE therapy, which binds to alpha-1, alpha-2, beta-1, beta-2, and beta-3 receptors; analysis revealed that NE treatment within the first two days of TBI was associated with slower return to normal vasomotor reactivity (Haenggi et al., 2012). Moreover, adding dobutamine, which stimulates beta-1 receptors, to NE therapy failed to produce significant effects (Haenggi et al., 2012). A third study tested the effects of verapamil, which blocks voltage-dependent calcium channels, in combination with NE after FPI and found that combinatorial therapy resulted in a restoration of regional cerebral blood flow at the location of the injury and elsewhere in the cortex compared to untreated injured rats (Maeda et al., 2005).

Despite the beneficial effects of NE on CPP, there are some adverse effects associated with NE treatment including an increase in interleukin 6 after experimental TBI, beyond the spike due to the injury itself (Stover et al., 2003). Another potential consequence of NE therapy is an alteration in creatinine clearances (CrCl) both while NE treatment is being administered and following it’s discontinuation (Udy et al., 2010); it is hypothesized that these changes in CrCl may impact renal excretion of other drugs used to treat TBI and any existing comorbid conditions. Another study stimulated isolated platelets obtained from 36 healthy volunteers and 11 TBI patients categorized as being in critical condition. The research team found that NE infusion was less effective in TBI patients during the first week of injury; in the second week post-injury TBI patients’ platelets exhibited hyper-susceptibility to NE exposure which coincided with increased intracranial pressure (ICP) and reduced saturation of blood within the jugular vein (Tschuor et al., 2008). The authors conclude that the differences observed over time in this study may be reflective of alterations in receptor levels over time (Tschuor et al., 2008). A clinical study tested the serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor milnacipran and found it reduced depression and improved cognitive function (Kanetani et al., 2003). Overall, there is a need for additional evidence surrounding the efficacy and safety of NE therapy after TBI.

3.3 Antagonists

In addition to the beta blockers described in Section 4 of this review, alpha blockers have also been tested in TBI. For example, in experimental TBI, pretreatment with prazosin, a blocker of post-synaptic α-1 adrenergic receptors, has been associated with increased hippocampal edema 1 day after injury; this study suggests that alpha-1-adrenoreceptor blockade after TBI produces deleterious effects (Dunn-Meynell et al., 1998). The authors of this study caution that blocking NE release may compound TBI pathology. Taken together, it suggests that the spike in endogenous NE after TBI may be protective (Dunn-Meynell et al., 1998).

4. Epinephrine

4.1 Overview

Epinephrine (EPI), also called adrenaline, is a catecholamine produced by chromaffin cells within the adrenal medulla as well as in some neurons (von Bohlen und Halbach and Dermietzel, 2006). The presence of EPI within the brain is well-established (Beart, 1979; Gunne, 1962; Vogt, 1954), as is the ability of neural tissue to produce EPI (Ciaranello et al., 1969; Hökfelt et al., 1973; Pohorecky et al., 1969). Relative to the other catecholamines discussed in this review, EPI is found in low concentration within the brain (Beart, 1979; Gunne, 1962). EPI is produced by methylation of NE by phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT), an endogenous enzyme as depicted in Figure 1 (Pohorecky and Baliga, 1973); several drugs are known to inhibit this PNMT (Fuller et al., 1971; Sall and Grunewald, 1987), though the effect of these drugs in the context of TBI remains unknown. EPI is implicated in the fight or flight response (Peet et al., 2013) and is up-regulated when the CNS processes stressful stimuli. EPI is also believed to underlie the stress response observed in post-traumatic stress disorder, a common co-morbidity in TBI survivors (Toth et al., 2013). TBI is known to result in an acute spike in EPI levels as depicted in Figure 2 (Lang et al., 2015; Rosner et al., 1984). Preclinical trials suggest strain-specific differences in PNMT exist. For example, in F344 rats activity of this enzyme is more than four times that in BUF rats; notably, in this study enzyme rates were inversely proportional to receptor density (Perry et al., 1983). In a publication studying clinical TBI, the authors reported a four-to-five-fold increase in EPI levels among TBI survivors with a GCS of 3–4; however, the same study found that TBI survivors with a GCS greater than 11 experienced either no spike or only a slight elevation (Hamill et al., 1987). In addition to TBI affecting the endogenous release of EPI, evidence suggests TBI impacts its metabolism of as well. Specifically, after pediatric TBI, epinehrine excretion in the form of urinary metanephrine (see Figure 2) increases when compared to healthy control and children diagnosed with ADHD (Konrad et al., 2003). The effect of this increased metabolism is yet to be fully determined including whether this has any pathophysiological consequences. Additional research characterizing post-TBI changes in EPI that occur after TBI is warranted, including studies trialing agonists and antagonists, as described in sections 4.2 and 4.3, respectively.

4.2 Agonists

Notably, EPI and the synthetic form, phenylephrine (a direct α-1 adrenergic agonist), is administered to TBI patients, not to target brain pathology, but rather because of its actions as a vasopressor. However, not all patients receiving a vasopressor are given EPI, as vasopressor selection depends on several factors. Moreover, published evidence suggests that EPI is often not the most common post-TBI pressor choice among prescribers. One study found that physians were more likely to prescribe EPI for their younger pediatric TBI patients, but tended to favor norepinephrine or phenylephrine for older pediatric patients (Di Gennaro et al., 2011). Compared to dopamine agonists, discussed in section 2.2, evidence is more limited rearding EPI agonists after TBI. It is notable that EPI has several clinical contraindications (e.g. sulfate sensitivity; diagnosis with closed-angle glaucoma) and several drugs that epinephrine is known to interact with (e.g. tricyclic antidepressants, halogenated anesthetics, and beta blockers). Similarly, phenylephrine has known interactions with tricyclic antidepressants as well as monamine oxidase inhibitors. Also worth noting is that EPI binds to the majority of adrenergic receptors; thus, EPI may result in systemic effects more so than agonists specific to a more limited number of receptor subtypes, such as dopamine and norepinephrine, as discussed in section 2.2 and 3.2, respectively.

4.3 Antagonists

Relatively little is known regarding therapeutic applications of drugs that block the activity of EPI. Though not specific to EPI, beta-adrenergic blockade has been trialed after TBI with some success. For example, a large study of 2601 TBI patients, including 506 patients treated with beta blockers found that beta blocker users had substantially lower mortality compared to their untreated counterparts (Schroeppel et al., 2010); the authors conclude that beta blockers may be an inexpensive and safe way to prevent mortality after TBI. Another study found improved survival with beta blocker treatment after TBI (Cotton et al., 2007).

Beta blockers have also been used for symptomatic relief of TBI-related intestinal dysfunction and reduced permeability, two related symptoms associated with the surge of EPI seen in TBI. One study trialing the beta blocker labetalol in a rat model reported improved intestinal permeability after experimental TBI, along with reduced SNS hyperactivity as evidenced by plasma EPI levels at 3 acute and subacute timepoints (Lang et al., 2015). A systematic review study examined the use of beta-2 receptor antagonists after TBI and concluded that many of the published studies were limited by poor methodology and/or small sample size; however, overall the evidence suggests that beta-2 receptor blockade may reduce cerebral edema and lead to attenuation of TBI-induced functional deficits (Ker et al., 2009). Evidence from a study examining genetically modified mice lacking the β2-adrenergic receptor found that knockout mice had favorable outcomes after ischemia-induced brain injury (Han et al., 2009). Overall, evidence suggests adrenergic blockade after TBI may be beneficial, though additional research is needed.

5 Remaining Gaps and Future Research Directions

Both pre-clinical and clinical evidence suggest that targeting the catacholaminergic system after TBI may ameliorate cellular and functional dysfunction. Of the three main catecholamines (dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine) described in this review (see: sections 2, 3, and 4, respectively), DA is the most extensively studied and has the most promising evidence to date. There are several phase I and phase II clinical trials indicating the benifical effects of targeting dopamine. Still, there is limited evidence surrounding the beneficial role epinephrine and norepinephrine can play post TBI.

Additional evidence is needed regarding therapeutic targeting of catecholamines after TBI. Studies are strengthened by inclusion of both acute and chronic timepoints. Similarly, rigor and thoughtful study design are important in generating high-quality evidence surrounding the roles of catecholamine agonists and antagonists, as well as drugs that target catecholamines indirectly. For example, care should be given to selection of the treatment regimens (e.g. dosage, timing, duration, route) based on available literature, known drug properties, and any patient contraindications; this will be relevant to the quest to successfully translate novel TBI therapeutics to the bedside. Part of this effort should include further examination of combination therapy, for example, simultaneous targeting of D1 and D2 receptors.

There are several barriers to developing and testing novel TBI therapeutics. TBI is clinically complex and includes diverse pathophysiological processes including inflammation, cell death, excitotoxicity, and multiple changes to catecholamines, to name a few. Thus, the development of drugs will be complex and require transdisciplinary collaboration. Further, there are several known factors complicating translation of catecholaminergic and other therapies to TBI care (Tolias and Bullock, 2004), including confounding effects of genetic variability (Yue et al., 2015), polytrauma in human TBI patients (Capone-Neto and Rizoli, 2009; Ladanyi and Elliott, 2008), drug reactions (Muir, 2006), and issues related to breaches in the blood–brain barrier (Folkersma et al., 2009; Whalen et al., 1998).

There are also additional challenges to targeting catecholamines specifically. For example, because of the shared production pathway of DA, NE, and EPI (see Figure 1), drugs targeting this pathway by blocking tyrosine hydroxylation or L-DOPA decarboxylation, will be non-specific and lower endogenous DA, NE, and EPI (Fuller, 1982). Similarly, drugs targeting DA β-hydroxylation will lower endogenous NE and EPI. Only PNMT inhibition would be specific to lowering EPI, by stopping methylation of NE to EPI. Administering exogenous catecholamines is complicated by the fact that many of the catecholamines bind to several receptor subtypes; for example, α-1 and β-1 receptors bind to DA, NE, and EPI, while α-2 respond to NE and EPI, and β-2 respond to EPI specifically. Additionally, there is the potential for systemic (therapeutic and adverse) effects of treatment due to the fact that catecholaminergic receptor subtypes are found throughout the body. For example, α-1 receptors are located in vasculature, bladder, and eyes; α-2 receptors are found within pre-synaptic nerve terminals; and β-1 receptors are located in the heart and kidneys. Overall, targeting the catecholaminergic system represents a complex, but potentially beneficial therapeutic avenue to promote TBI recovery.

Replication of promising experimental findings and expansion of the work to other models and eventually human trials will be facilitated by thorough dissemination of study findings; this includes detailed reporting of important experimental endpoints in research publications and presentations, as outlined in the recently published 2nd version of the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke’s Common Data Elements for TBI research (National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke, 2015; Smith et al., 2015). To promote clinical relevance and translatability, personal and genetic characteristics that may affect response to therapies targeting the catacholamines should be considered; when possible, stratified analysis by genotype or control for genetic variation should be used (Wagner et al., 2007). For example, because sex differences in TBI outcomes have been reported, sex is an important factor to consider when trialing DA therapies (Ratcliff et al., 2007; Slewa-Younan et al., 2004). Indeed, sex-specific differences in outcome have been reported (Wagner et al., 2007). Similarly, genetic variation and differential expression in DAT and other DA-, NE-, and EPI- related genes including the enzymes responsible for synthesis and metabolism of these compounds may be relevant when trialing novel therapies for effectiveness and adverse effects (Failla et al., 2013; Zhuang et al., 2001). There is known genetic variation in the catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) gene which encodes an enzyme responsible for degrading catecholamines; clinically, variation in COMT has been associated with cognitive impairment after mild TBI (Yue et al., 2015); variation in other genes related to pharmacogenomic response (e.g. CYP2C9; VKORC1) should also be explored. Understanding the role of molecular genetic and genomic factors may be relevant in the quest to successfully translate catecholamine-targeting drugs to TBI clinical care. Furthermore, gene-gene and gene-environment interactions should be considered, including the effects of environmental enrichment (experimental rehabilitation) on catecholamines and outcomes of brain injury (Shin et al., 2013; Wagner et al., 2005a).

6 Conclusion

Existing evidence suggests that TBI pathology results in several changes to the catecholamine system including downregulation of D2 receptors, upregulation of D1 receptors, and spikes in EPI, NE, and DA levels as depicted in Figure 2. Subsequently, researchers have tested several drugs targeting catecholamines directly or indirectly using pre-clinical models and clinical trials as described throughout this review and summarized in Table 1. For example, indirect and direct targeting of DA after TBI has been associated with beneficial effects on memory, learning, executive function, and other aspects of cognition (Armstead et al., 2013). Notably, evidence is more limited regarding the role of epinephrine agonists, NE agonists (Forsyth and Jayamoni, 2003), and monoamine agonists more broadly (Forsyth et al., 2006). Overall, additional evidence is needed regarding how to best target the catecholaminergic system to improve outcomes of TBI. Pre-clinical studies are useful in exploring cellular targets of drugs and providing preliminary evidence regarding the safety and efficacy of catecholamine-targeting drugs for improving functional outcomes. Additional clinical evidence is especially needed to confirm safety and of these drugs for treating human TBI and ultimately translate these therapies to clinical care.

Table 1.

Summary of all studies included in this review which therapeutically targeted catechoamines after traumatic brain injury. The therapeutic agent name, mechanism of action/target receptor(s), study subjects, doses tested, and outcomes are included.

| Agent Name | Mechanism/Target | Study Subjects | Doses Tested | Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amantadine | Increases DA release; blocks DA reuptake. Binds NMDA receptor | Patients with severe TBI (N=74) divided into treated and untreated groups | Standard therapy + 200 mg amantadine administered intravenously twice daily for 3 days, starting 3 days after initial hospitalization | In the group of patients with severe brain injuries treated with standard therapy plus amantadine the outcome GCS was higher and the case fatality rate lower than in the group treated with standard therapy alone. | Saniova, et al., 2004 |

| Patients with severe TBI (N=184) treated with amantadine (N=87) or placebo (N=97) | 100mg of amantadine for 2 weeks (vs. placebo) which was increased to 150mg week 3 and 200mg week 4 | Amantadine accelerates recovery as assessed using the disability rating scale in patients with severe TBI. | Giacino, et al., 2012 | ||

| 2 individuals recovering from TBI who were experiencing behavioral problems that were difficult to treat | Amantadine therapy as part of TBI management | Amantadine treatment reduced symptoms of agitation and aggression. | Chandler, et al., 1988 | ||

| 168 TBI patients (6+ months post-injury) divided into amantadine (N=82) or placebo (N=86) | 100 mg of amantadine given twice daily over a 60-day treatment course | TBI survivors and clinicians reported lower irritability at the 60 day follow-up assessment. | Hammond, et al., 2015 | ||

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats (N=42) exposed to CCI or sham | Daily treatment with 10 mg/kg amantadine (vs. placebo) administered for 18 days | Amantadine did not promote motor recovery or hippocampal neuron survival; amantadine modestly improved MWM performance | Dixon, et al., 1999 | ||

| Rats (N=130) exposed to FPI or sham | 15, 45, or 135 mg/kg/day of amantadine administered intraperitoneally 3 times daily for 16 consecutive days | Treatment with 135mg/kg/improved learning and cognition and preserved hippocampal neurons. | Wang, et al., 2013 | ||

| Rats (N=130) exposed to cortical FPI or sham broken down into subgroups based on parameters & measures | Chronic subcutaneous infusion with 3.6mg/kg/day of amantadine or saline vehicle at a release rate of 0.15 mL/hr | Amantadine ameliorated post-injury dopamine-release deficits as well as cognitive and motor deficits as assessed using novel object recognition and other behavioral tests | Huang, et al., 2014 | ||

| Pramipexole | DA Agonist at D2, D3, and D4 | Children and adolescents (N=25) experiencing a low-level of responsiveness at least 1 month after TBI | Treated with pramipexole or amantadine with a dosage that was based on age and increased over 4 weeks and then weaned for the next 2 weeks | Amantadine and pramipexole were similarly effective without significant side effects. Both dopamine agonists supported restoration arousal, awareness, and communication. The authors conclude that both DA agonists accelerated rehabilitation after brain injury, warranting additional study | Patrick, et al., 2006 |

| Bromocriptine | Agonist at D2 | Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats exposed to CCI or sham (N=74 across 2 experiments with group sizes of 5–15) | 5 mg/kg intraperitoneal bromocriptine or vehicle administered 15 minutes pre-injury | Bromocriptine was associated with reduced lipid peroxidation and enhanced spatial learning on the MWM | Kline, et al., 2004 |

| Adult male rats exposed to CCI or sham (N=73 across 2 experiments with group sizes of 10–17) | 5 mg/kg intraperitoneal bromocriptine (vs. vehicle) starting 24 hr post-injury, with continued daily injections | Bromocriptine treatment following experimental TBI enhanced working and spatial memory assessed via MWM. CCI+ bromocriptine was associated with more morphologically intact CA3 neurons than the injured vehicle-treated group | Kline, et al., 2002 | ||

| 24 TBI survivors at least 4 weeks post-injury at time of testing | 2.5 mg bromocriptine (vs. placebo) in crossover study | Bromocriptine improved executive function and duel-task performance; other assessments of cognitive function showed no effect of treatment | McDowell, et al., 1998 | ||

| 26 mild TBI survivors (1 month post-injury) + 31 healthy controls | 1.25 mg oral bromocriptine (vs. placebo) | Among healthy controls, bromocriptine led to better memory performance; TBI survivors were not responsive. | McAllister, et al., 2011 | ||

| Methamphetamin e | Stimulant that agonizes several receptors including trace amine-associated receptor 1 and alpha-2 | Adult male Wistar rats (N=34) exposed to severe TBI modeled using lateral FPI (vs. sham) | Intravenous bolus 0.845mg/kg of methamphetamine (vs. saline) given 3 hours post-injury followed by continuous intravenous infusion 6.7 microliters/hour | Low-dose methamphetamine treatment reduced behavioral and cognitive consequences of TBI as assessed using neurological severity score, the foot fault test, and MWM. Methamphetamine treatment was also associated with reduced apoptotic cell death and an increase in immature neurons. | Rau et al., 2012 |

| Adult male CD1 mice (N=88) exposed to mild TBI modeled using temporal weight drop injury (vs. sham) broken into subgroups based on sacrifice time point | 5 mg/kg methamphetamine (vs. saline) administered intraperitoneally 30 min prior to injury | In this study administration of low-dose methamphetamine exacerbated the deficits in dopamine turnover occurring after experimental brain injury. Suppression of locomotor response was also worsened following treatment as assessed using locomotor activity chambers for up to 72 hours. | Shen et al., 2011 | ||

| Lisuride | DA agonist binds D2, D3, and D4 (among other receptors) | Male Sprague-Dawley rats (N=70) exposed to TBI modeled using TBI (vs. sham) | 0.3 mg/kg loading dose followed by 0.5 mg/kg/day maintenance doses lisuride (vs. placebo) administered via subcutaneous implanted osmotic pumps for the study duration (7 days) | Lisuride reduced the number of post-TBI seizures and the seizures that did occur were shorter than those in untreated animals. The loading dose lowered blood pressure but the contusion volumes and behavioral performance did not differ across the groups. | Zweckberger, et al., 2010 |

| Methylphenidate | DA & NE reuptake inhibitor; binds and blocks DA and NE transporters | 15 TBI patients who received methylphenidate as part of a double-blind, controlled, crossover trial | Methylphenidate treatment continued in the patients for a year | Methylphenidate led to modest improvement of some symptoms was reported although the crossover design led to some carryover effects. | Gualtieri et al., 1988 |

| 38 adult males who had experienced TBI and were beyond the rapid recovery period in a single-bind pre-test/post-test placebo-controlled trial | Subjects received methylphenidate (30 mg/day) or placebo for a 6 week treatment period | Methylphenidate was well-tolerated and a significant drug/time interaction effect was reported; less impairment on general psychopathology and memory tests was also reported, though other measures (e.g. attention) were unchanged. | Mooney, et al., 1993 | ||

| 11 patients with acute TBI in a prospective multiple baseline design | Patients were administered increasing doses of methylphenidate, which reached a 15 mg dose twice daily after 1 week | Methylphenidate treatment was well-tolerated and associated with modestly improved recovery as assessed using the Disability Rating Scale. Treatment also led to improvements in attention and cognition as assessed using validated tests including: Digit Span, Mental Control, and Symbol Search. | Kaelin, et al., 1996 | ||

| 12 closed head injury patients assessed 14+ months post-injury in a double-blind placebo-controlled, crossover trial | Methylphenidate (0.3 mg/kg) administered twice daily (vs. placebo) | No significant differences were reported on tests of learning, cognitive processing, attention, or social behavior. | Speech, et al., 1993 | ||

| N=6 TBI patients examined before, during, and after methylphenidate therapy | Methylphenidate treatment with dosage increasing over 2 weeks (5–10mg) followed and then reduced over an additional 2 weeks | A visual spatial attention task revealed that TBI patients had relatively worse performance on leftward hemifield shifts (vs. right) and that the difference in left and right performance was ameliorated by methylphenidate. | Pavlovskaya et al., 2007 | ||

| 30 mild-to-moderate TBI patients randomized to 3 treatment groups (n=10/group) | Methylphenidate starting at 5 mg/day, and increasing to 20mg/kg in a week vs. placebo. *Note also tested sertraline (included later in this table) @2 5mg/day then 100 mg/day at 1 week) | Methylphenidate reduced depressive symptoms, cognitive dysfunction, and daytime sleepiness after TBI without otherwise altering recovery. *Sertraline reduced depressive symptoms only. Methylphenidate was better tolerated. | Lee, et al., 2005 | ||

| 23 patients with mild to severe TBI in a doubleblind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial | Treatment with methylphenidate (30 mg/kg) or placebo starting the day after baseline assessment and for 30 days thereafter | Methylphenidate enhanced the rate but not the overall extent of recovery as assessed using the Disability Rating Scale and assessments of vigilance. | Plenger et al., 1996 | ||

| Male Sprague-Dawley (N=24) rats exposed to CCI (vs. sham) | Methylphenidate (5 mg/kg) or vehicle intraperitoneally 24hrs post-TBI and daily for 18 days | Methylphenidate did not improve motor recovery as assessed using the beam balance or beam walking task, but it did improve learning on the MWM. | Kline et al., 2000 | ||

| 34 patients with attention problems in the post-acute phase of moderate-to-severe TBI divided into a pilot & replication sample in a double-blind, placebo controlled, crossover study | Methylphenidate (0.3 mg/kg twice daily); 24.4 mg (range, 15–40); one day washout before crossover | Beneficial effects were found on 5 of the 13 attentional factors 3 of which were significant in the replication sample. Several variables showed no significant treatment effect and those that did had a small-to-moderate effect size. | Whyte et al., 2004 | ||

| Adult rats (N=45) exposed to unilateral sensorimotor cortex lesion | Amphetamine (2 mg/kg) vs. vehicle given with physio-therapy (PT) on days 2 and 5 post-injury; PT continued twice daily for 3 weeks | Amphetamine treated rats had better performance on forelimb reaching and ladder rung walking. Amphetamine was also found to increase the growth of axons in the deafferented basilar pontine nuclei. | Ramic et al., 2006 | ||

| Amphetamine | Indirect activation of D1 and A2 receptors (among others) and potent agonist of trace amine-associated receptor 1. Promotes DA release and prevents reuptake via binding to DAT. | Rats (N=48) exposed to CCI (vs. sham) | Amphetamine (1mg/kg/day) or saline vehicle administered via an ALZET pump for 7 days | Amphetamine led to elevated BDNF, an increased ratio of P-synapsin-to-total synapsin, and decreased carbonyl groups on proteins but did not improve motor function. | Griesbach et al., 2008 |

| Rats (N=25) exposed to unilateral contusion injury (vs. sham) broken into subgroups by treatment | Amphetamine (2 mg/kg) administered as a single intraperitoneal injection 24 hours post-injury | Amphetamine accelerated recovery, increased CMRglu, and partly reduced hypometabolism. | Queen et al., 1997 | ||

| Rats (N=30) exposed to lateral FPI (vs. sham) | Amphetamine (4 mg/kg) administered intraperitoneally 5 minutes post-injury (vs. saline) | Amphetamine attenuated the increased lactate and free fatty acid levels in the ipsilateral left cortex and hippocampus at 30 min and 60 min after injury. | Dhillon et al., 1998 | ||

| Cats (N=23) exposed to bilateral visual cortex ablation | Amphetamine (5mg/kg) alone or with 0.4mg/kg haloperidol (vs. saline control) | Amphetamine led to rapid, enduring recovery after visual cortex ablations; 2 of the treated cats performed to the level of binocular vision. Haloperidol blocked amphetamine’s effects. | Hovda et al., 1989 | ||

| Rats exposed to fimbria lesion | Amphetamine (0.5 mg/kg) given prior to testing and daily thereafter (vs. control) | Performance on tasks was impaired after fimbria lesion and amphetamine attenuated deficits. | M’Harzi et al., 1988 | ||

| Rats (N=111) exposed to unilateral motor cortex ablation (vs. sham) | Amphetamine (0.5-, 1-, 2-, or 4- mg/kg) vs. saline administered 24 hours post injury | Amphetamine accelerated recovery which was blocked by haloperidol* (*also in table) or post-amphetamine restraint. | Feeney et al., 1982 | ||

| Haloperidol | Anti-psychotic that binds D1, D2, D3, D4, D5, and A1 receptors among other receptors; antagonizes DA | TBI patients (N=3) undergoing rehabilitation | Tapering therapy with antipsychotic (thorazine vs. haloperidol) therapy | Participants were assessed on baseline, prior to tapering, and 1 and 3 weeks post-discontinuation using a variety of neuropsychiatric tests. The magnitude of improvement was better after thorazine discontinuation (vs. haloperidol). | Stanislav et al., 1997 |

| Rats (N=142) undergoing unilateral suction ablation to the sensorimotor cortex (vs. sham) | Haloperidol (0.1, 1.0, or 10.0 mg/kg), clozapine (0.1, 0.6, 1.0, or 10.0 mg/kg) or placebo, given intraperitoneally in a single dose 24 hr post-TBI | In control animals, there was no significant effect of haloperidol or clozapine on motor outcome; all haloperidol doses slowed motor recovery which persisted after 2 weeks. Rats given a single dose of clozapine of 1.0 or 10.0 mg/kg had poorer recoveries, though only the highest dose differed from controls and the effect was no longer seen by 2 weeks. | Goldstein & Bullman, 2002 | ||

| Risperidone | Atypical anti-psychotic; DA antagonist with anti-adrenergic and other properties; binds D1, D2, D3, D4, D5, and several alpha receptors | A single 69 year old male patient who sustained a TBI 5 months prior with symptoms of aggression and delusion | 2mg risperidone per day. After 2 weeks he was given 10 mg of donepezil daily for cognitive impairment | Risperidone improved his symptoms by 2 weeks. After 6 weeks on risperidone and donepezil he exhibited Parkinsonianism in the absence of decreased dopamine transporter function; the adverse symptoms disappeared rapidly after discontinuation. | Kang & Kim, 2013 |

| Male rats (N=54) receiving CCI (vs. sham). | Risperidone (0.45 mg/kg), haloperidol (0.5 mg/kg)* (also in table), or vehicle (1mL/kg) administered intraperitoneally daily starting 24 hr post-injury and continuing for 19 days | Both antipsychotics led to poorer learning assessed using MWM, and risperidone also led to delayed motor recovery; there was no effect on histological outcomes. | Hoffman et al., 2008 | ||

| Fluoxetine | Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor binds to DAT among other receptors | Adult male C57BL/6 mice (N=145) exposed to CCI (vs. sham) | Fluoxetine (10 mg/kg/day) for a total of four weeks administered intraperitoneally | Fluoxetine enhanced hippocampal Neuroplasticity but did not improve outcomes on behavioral tests including the Catwalk-assisted gait test and Barnes Maze. | Wang et al., 2011 |

| Escitalopram | Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor | Adult male Wistar rats (N=12) exposed to TBI modeled using weight drop impact acceleration TBI (vs. sham) | Escitalopram (10mg/kg), venlafaxine (10mg/kg), bupropion (20mg/kg), and amitriptyline (10mg/kg) were tested | Chronic treatment with the antidepressants tested (escitalopram and venlafaxine) was associated with lower depressive/anxiogenic-like behavior assessed using a neuropsychiatric battery after experimental TBI. | Mahesh et al., 2010 |

| Sertraline | Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor; DA reuptake inhibitor (not tight binding). Binds alpha-1 (antagonist) | 99 individuals who had experienced TBI within the past 8 weeks, some of whom received placebo (N=50) and others sertraline (N=49) | Sertraline (50 mg) vs. placebo therapy administered orally for 3 months | Sertraline did not improve cognitive function (vs. placebo) assessed via a testing battery (e.g. Wechsler Memory Scale, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Symbol-Digit Modalities Test, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, and Neurobehavioral Functioning Inventory). No adverse effects occurred. | Baños et al., 2010 |

| 11 patients with severe TBI (and presumed diffuse axonal injury) occurring due to a motor vehicle crash within 2 weeks | Sertraline (100 mg/day) for 2 weeks (vs. placebo) | Recovery was similar across the groups on measures of alertness, agitation, & cognition (Orientation Log, Agitated Behavior Scale, & Galveston Orientation Test); no adverse effects were reported. | Meythaler et al., 2001 | ||

| 52 patients who had survived a mild, moderate, or severe TBI (17+/−14 years ago) who were also diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder | Sertraline (25 mg starting dose which was increased to a therapeutic level up to 200mg) or placebo, administered orally every day for 10 weeks | Both groups improved over time on measures of mood, anxiety, and QO (e.g. HAM-D; Beck Anxiety Inventory; Life-3 Quality of Life); 59% of the experimental group and 32% of the placebo group responded to the treatment for depression, though the groups did not differ significantly. | Ashman et al., 2009 | ||

| 99 individuals with TBI within the 8 weeks; N=50 got placebo (N=50) and N=49 sertraline | Sertraline (50 mg) administered daily for 3 months by mouth | In the first 3 months, the placebo group had greater depressive symptoms than those receiving sertraline; after discontinuation no difference was found (out to 1 year). | Novack et al., 2009 | ||

| Norepinephrine | Agonist that binds alpha-1, alpha-2, beta-1, beta-2, and beta-3 receptors | TBI patients with normal serum creatinine concentrations (N=20) | Observational study of some patients who received norepinephrine therapy (varied dose) for cerebral perfusion pressure | 85% of the sample exhibited augmented creatinine clearances. Multivariate analysis identified several factors associated with augmented clearance including NE use among other personal and treatment factors | Udy et al., 2010 |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats (N=35) exposed to experimental TBI (N=20) or sham (N=15) | Norepinephrine infusion (vs. saline control) for 90 minutes at either 4 or 24 hr post-TBI | TBI increased IL-6 (vs. sham); NE therapy increased IL-6 at 7 and 27 hr post-TBI in plasma and at 7 hr. post-TBI in CSF. | Stover et al., 2003 | ||

| TBI patients (N=11) and healthy volunteers (N=36) provided platelets for this study | Norepinephrine was administered to some TBI patients as part of their clinical care (varied dose) | During the first week after TBI, norepinephrine-mediated stimulation of isolated platelets was reduced compared to control). During the second week P-selecting and microparticle-positive platelets were lower in TBI survivors. | Tschuor et al., 2008 | ||

| Pediatric patients with moderate-to-severe TBI (N=82) | This retrospective study compared vasopressors including varied doses of NE, phenylephrine, etc. | NE or phenylephrine in older patients (EPI in younger). NE was associated with higher CPP and lower intracranial pressure (at 3hr). | Di Gennaro et al., 2001 | ||

| 13 severe TBI patients; some (n=8) of whom received NE and dobutamine) due to a clinical indication | Some of the patients in this retrospective study received NE and dobutamine treatment as part of their clinical management (doses varied) | Patients who did not receive catecholamine treatment had a mean VMR index that recovered within 48–72 hr of injury which was not true with NE treatment. Adding dobutamine to NE failed to significantly change vasomotor reactivity in this study. | Haenggi et al., 2012 | ||

| Young male Sprague-Dawley rats (N=30) exposed to lateral FPI (vs. sham) | Intravenous NE (20 microgram/mL/min) + verapamil (200 micrograms/kg/min) | In rats treated with VE+NE all cortical areas measured showed near normal reactivity of the vasculature to direct cortical stimulation. | Maeda et al., 2005 | ||

| Milnacipran | Serotonin/NE reuptake Inhibitor; acts as a serotonin agonist | 10 adult TBI patients | Milnacipran was administered to patients at a dose of 30–150 mg in a 6 week open study verapamil | Adverse effects were experienced by one patient experienced side effects, though they were not serious, but none were deemed serious. Patients on milnacipran had improvement in cognitive function as on the Mini Mental Status Exam. | Kanetani et al., 2003 |

| Prazosin | NE antagonist; blocker of post-synaptic alpha-1 receptors; | Adult male rats (N=24) exposed to unilateral cerebral contusion (vs. sham) | Prazosin (3 mg/kg) or the NE-reuptake blocker desmethylimipramine (10 mg/kg) vs. vehicle administered intraperitoneally 30 minutes prior to TBI | Pre-treatment with prazosin resulted in edema in the striatum and hippocampus at 24 hr compared to the other groups. The authors conclude that the increase in NE after TBI plays an important role and that blocking this can be detrimental. | Dunn-Meynell et al., 1998 |

| Beta blockers | Antagonist at beta-1, beta-2, and/or beta-3 receptors | This retrospective study examined medical records of 2601 TBI patients including 506 treated at a Level 1 Trauma Center using beta blockers | Some of the records reviewed (N=506) were from people who received beta blockers (varied doses) as part of their TBI clinical management | After adjusting for age, injury severity, and transfusions multivariable analysis revealed beta blocker treated led to lower mortality. | Schroeppel et al. 2010 |

| TBI patients from the American College of Surgeons database (N=420) inpatient 4–30 days, some received beta blockers (N=174) some did not (N=246) | Beta-blocker exposure defined as any beta-blocker regimen (varied doses) lasting 2+ days | There was a higher survival with beta blocker treatment, which is especially notable since the group receiving beta blockers was older, and older TBI patients usually have higher mortality. | Cotton et al., 2007 |

Acknowledgments

This work was generously supported by several grants, including: R01NS079061, R01NS091062, VA RR&D #B1127-1, F31NR014957 and T32NR009759. Additional support for this work was provided by grants from the following foundations and professional societies: The Pittsburgh Foundation, Sigma Theta Tau International Eta Chapter, the International Society for Nurses in Genetics, and the American Association of Neuroscience Nursing/Neuroscience Nursing Foundation. The authors would like to thank Marilyn K. Farmer and Amanda Savarese for their continued editorial support and Michael D. Farmer for generously volunteering his time and talents to make the figures.

References

- Abi-Dargham A, Moore H. Prefrontal DA transmission at D1 receptors and the pathology of schizophrenia. Neuroscientist. 2003;9:404–16. doi: 10.1177/1073858403252674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GE, Crutcher MD. Functional architecture of basal ganglia circuits: neural substrates of parallel processing. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:266–71. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90107-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arciniegas D, Topkoff J, Silver J. Neuropsychiatric Aspects of Traumatic Brain Injury. Curr Treat Opin Neurol. 2000;2:169–186. doi: 10.1007/s11940-000-0017-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armentero MT, Fancellu R, Nappi G, Blandini F. Dopamine receptor agonists mediate neuroprotection in malonate-induced striatal lesion in the rat. Exp Neurol. 2002;178:301–5. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.8033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead WM, Riley J, Vavilala MS. Dopamine prevents impairment of autoregulation after traumatic brain injury in the newborn pig through inhibition of Up-regulation of endothelin-1 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:e103–11. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182712b44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashman TA, Cantor JB, Gordon WA, Spielman L, Flanagan S, Ginsberg A, Engmann C, Egan M, Ambrose F, Greenwald B. A randomized controlled trial of sertraline for the treatment of depression in persons with traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:733–40. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo BA, Kelley AE. Discrete neurochemical coding of distinguishable motivational processes: insights from nucleus accumbens control of feeding. Psychopharmacol. 2007;191:439–59. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0741-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales J, Wagner A, Kline A, Dixon C. Persistent cognitive dysfunction after traumatic brain injury: A dopamine hypothesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:981–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baños JH, Novack TA, Brunner R, Renfroe S, Lin HY, Meythaler J. Impact of early administration of sertraline on cognitive and behavioral recovery in the first year after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2010;25:357–61. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181d6c715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbay S, Nudo RJ. The effects of amphetamine on recovery of function in animal models of cerebral injury: a critical appraisal. Neuro Rehabilitation. 2009;25:5–17. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2009-0495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beart PM. Adrenaline The cryptic central catecholamine. Trends Neurosci. 1979;2:295–297. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(79)90115-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW. Neural substrates of psychostimulant-induced arousal. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2332–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder LM. Persisting symptoms after mild head injury: a review of the postconcussive syndrome. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1986;8:323–46. doi: 10.1080/01688638608401325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogner J, Barrett RS, Hammond FM, Horn SD, Corrigan JD, Rosenthal J, Beaulieu CL, Waszkiewicz M, Shea T, Reddin CJ, Cullen N, Giuffrida CG, Young J, Garmoe W. Predictors of Agitated Behavior During Inpatient Rehabilitation for Traumatic Brain Injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:S274–S281.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett HM, Dietrich WD. Quantitative structural changes in white and gray matter 1 year following traumatic brain injury in rats. Acta Neuropathol. 2002;103:607–14. doi: 10.1007/s00401-001-0510-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brustolim D, Ribeiro-dos-Santos R, Kast RE, Altschuler EL, Soares MBP. A new chapter opens in anti-inflammatory treatments: the antidepressant bupropion lowers production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:903–7. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calipari ES, Ferris MJ. Amphetamine mechanisms and actions at the dopamine terminal revisited. J Neurosci. 2013;33:8923–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1033-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor JB, Gordon W, Gumber S. What is post TBI fatigue? Neuro Rehabilitation. 2013;32:875–883. doi: 10.3233/NRE-130912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone-Neto A, Rizoli SB. Linking the chain of survival: trauma as a traditional role model for multisystem trauma and brain injury. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009;15:290–4. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32832e383e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castriotta RJ, Murthy JN. Sleep disorders in patients with traumatic brain injury: a review. CNS Drugs. 2011;25:175–85. doi: 10.2165/11584870-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Fact Sheet [WWW Document] Inj Prev Control Trauma Brain Inj. 2015 URL http://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/get_the_facts.html (accessed 9.29.15)

- Centonze D, Gubellini P, Picconi B, Calabresi P, Giacomini P, Bernardi G. Unilateral dopamine denervation blocks corticostriatal LTP. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:3575–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.6.3575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler MC, Barnhill JL, Gualtieri CT. Amantadine for the agitated head-injury patient. Brain Inj. 1988;2:309–11. doi: 10.3109/02699058809150901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Bohanick JD, Nishihara M, Seamans JK, Yang CR. Dopamine D1/5 receptor-mediated long-term potentiation of intrinsic excitability in rat prefrontal cortical neurons: Ca2+-dependent intracellular signaling. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:2448–64. doi: 10.1152/jn.00317.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudasama Y, Nathwani F, Robbins TW. D-Amphetamine remediates attentional performance in rats with dorsal prefrontal lesions. Behav Brain Res. 2005;158:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciaranello RD, Barchas RE, Byers GS, Stemmle DW, Barchas JD. Enzymatic synthesis of adrenaline in mammalian brain. Nature. 1969;221:368–9. doi: 10.1038/221368a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools AR, Ellenbroek B, Heeren D, Lubbers L. Use of high and low responders to novelty in rat studies on the role of the ventral striatum in radial maze performance: effects of intra-accumbens injections of sulpiride. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1993;71:335–42. doi: 10.1139/y93-052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino M, Marino F. Adrenergic and dopaminergic modulation of immunity in multiple sclerosis: teaching old drugs new tricks? J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:163–79. doi: 10.1007/s11481-012-9410-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton BA, Snodgrass KB, Fleming SB, Carpenter RO, Kemp CD, Arbogast PG, Morris JA. Beta-Blocker Exposure is Associated With Improved Survival After Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. J Trauma-Injury Infect Crit Care. 2007 doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31802d02d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Roiser JP. Dopamine, serotonin and impulsivity. Neuroscience. 2012;215:42–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon HS, Dose JM, Prasad RM. Amphetamine administration improves neurochemical outcome of lateral fluid percussion brain injury in the rat. Brain Res. 1998;804:231–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00639-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Bassareo V. Reward system and addiction: what dopamine does and doesn’t do. Curr Opin Phamacol. 2007;7:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Gennaro JL, MacK CD, Malakouti A, Zimmerman JJ, Armstead W, Vavilala MS. Use and effect of vasopressors after pediatric traumatic brain injury. Dev Neurosci. 2011;32:420–430. doi: 10.1159/000322083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon C, Kraus M, Kline A, Ma X, Yan H, Griffith R, Wolfson B, Marion D. Amantadine improves water maze performance without affecting motor behavior following traumatic brain injury in rats. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 1999;14:285–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnemiller E, Brenneis C, Wissel J, Scherfler C, Poewe W, Riccabona G, Wenning GK. Impaired dopaminergic neurotransmission in patients with traumatic brain injury: a SPECT study using 123I-beta-CIT and 123I-IBZM. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27:1410–4. doi: 10.1007/s002590000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du F, Li R, Huang Y, Li X, Le W. Dopamine D3 receptor-preferring agonists induce neurotrophic effects on mesencephalic dopamine neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:2422–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn-Meynell AA, Hassanain M, Levin BE. Norepinephrine and traumatic brain injury: a possible role in post-traumatic edema. Brain Res. 1998;800:245–252. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00524-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer KFW, Bell R, McCann J, Rauch R. Aggression after traumatic brain injury: analysing socially desirable responses and the nature of aggressive traits. Brain Inj. 2006;20:1163–73. doi: 10.1080/02699050601049312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekdahl CT, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Brain inflammation and adult neurogenesis: the dual role of microglia. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1021–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsworth JD, Roth RH. Dopamine synthesis, uptake, metabolism, and receptors: relevance to gene therapy of Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 1997;144:4–9. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.6379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Failla MD, Burkhardt JN, Miller MA, Scanlon JM, Conley YP, Ferrell RE, Wagner AK. Variants of SLC6A4 in depression risk following severe TBI. Brain Inj. 2013;27:696–706. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2013.775481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Färber K, Kettenmann H. Physiology of microglial cells. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:133–43. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney DM, Gonzalez A, Law WA. Amphetamine, haloperidol, and experience interact to affect rate of recovery after motor cortex injury. Science. 1982;217:855–7. doi: 10.1126/science.7100929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernstrom JD. Role of precursor availability in control of monoamine biosynthesis in brain. Physiol Rev. 1983;63:484–546. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1983.63.2.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleckenstein AE, Volz TJ, Riddle EL, Gibb JW, Hanson GR. New insights into the mechanism of action of amphetamines. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:681–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkersma H, Boellaard R, Vandertop WP, Kloet RW, Lubberink M, Lammertsma AA, van Berckel BNM. Reference tissue models and blood-brain barrier disruption: lessons from (R)-[11C]PK11195 in traumatic brain injury. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1975–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.067512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth R, Jayamoni B. Noradrenergic agonists for acute traumatic brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD003984. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth RJ, Jayamoni B, Paine TC. Monoaminergic agonists for acute traumatic brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD003984. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003984.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller RW. Pharmacology of brain epinephrine neurons. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1982;22:31–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.22.040182.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller RW, Mills J, Marsh MM. Inhibition of phenethanolamine N-methyltransferase by ring-substituted .alpha.-methylphenethylamines (amphetamines) J Med Chem. 1971;14:322–325. doi: 10.1021/jm00286a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacino JT, Whyte J, Bagiella E, Kalmar K, Childs N, Khademi A, Eifert B, Long D, Katz DI, Cho S, Yablon SA, Luther M, Hammond FM, Nordenbo A, Novak P, Mercer W, Maurer-Karattup P, Sherer M. Placebo-controlled trial of amantadine for severe traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:819–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianutsos G, Chute S, Dunn JP. Pharmacological changes in dopaminergic systems induced by long-term administration of amantadine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1985;110:357–61. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90564-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein LB. Neuropharmacology of TBI-induced plasticity. Brain Inj. 2003;17:685–94. doi: 10.1080/0269905031000107179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein LB, Bullman S. Differential effects of haloperidol and clozapine on motor recovery after sensorimotor cortex injury in rats. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2002;16:321–5. doi: 10.1177/154596830201600402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granado N, Ortiz O, Suárez LM, Martín ED, Ceña V, Solís JM, Moratalla R. D1 but not D5 dopamine receptors are critical for LTP, spatial learning, and LTP-Induced arc and zif268 expression in the hippocampus. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:1–12. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]