Abstract

Objectives

To describe the methodology, challenges, and baseline characteristics of a prevention development trial entitled “Reducing Pain, Preventing Depression”.

Design

Sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART) comparing sequences of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and physical therapy for knee pain and prevention of depression and anxiety. Participants were followed for 12 months for new episode depression or anxiety.

Setting

Late-Life Depression Research Clinic.

Participants

Individuals 60 and older with knee osteoarthritis and subsyndromal depression, defined as PHQ-9 score of at least “1” (which included the endorsement of one of the cardinal symptoms of depression [low mood or anhedonia]), and no diagnosis of MDD per SCID.

Intervention

Sequential randomization to CBT, physical therapy, or enhanced usual care.

Measurements

Depression and anxiety severity and characterization of new episodes were assessed with the PHQ-9, GAD-7, and the PRIME-MD. Knee pain was characterized with the Western Ontario McMaster Arthritis Index. Response was defined as at least “Very Much Better” on a Patient Global Impression of Change.

Results

At baseline (n=99), average age=71, 61.62% are female, and 81.8% are Caucasian. The average PHQ-9 = 5.6 and average GAD7= 3.2. The majority were satisfied with the interventions and study procedures. We describe the challenges and our solutions which will be used in a confirmatory clinical trial of efficacy.

Conclusions

A SMART design for depression and anxiety prevention, utilizing both CBT and physical therapy, appears to be feasible and acceptable to participants. The methodological innovations of this project may advance the field of late-life depression and anxiety prevention.

Keywords: DEPRESSION, PREVENTION, PAIN, ANXIETY, LATE-LIFE

Introduction

Medical illness, functional disability, family and personal histories of mood disorders, social isolation, life stressors, bereavement, and neurodegenerative disorders are all putative risk factors for new onset major depressive disorder (MDD) and anxiety disorders in older adults. Osteoarthritis (OA) pain and associated disability are risk factors for a major depressive episode and possibly anxiety disorders,1 and treating OA pain and disability may reduce the severity of comorbid MDD and anxiety.2 Indeed, among older adults with MDD, a significantly higher proportion report pain that is disabling compared to those without MDD.3 Patients living with both conditions also have significantly worse health-related quality of life, greater somatic symptom severity, and higher prevalence of other pain disorders than chronic pain patients without depression.4 It is plausible that reducing pain and disability could actually prevent new onset cases of MDD and anxiety disorders, although this has not yet been tested. Since anxiety disorders increase risk for MDD5 and both conditions worsen comorbid medical burden and disability6, prevention interventions should aim to reduce the risk of developing both depression and anxiety in late-life.

Learning-based interventions such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)13 or a knee-specific physical therapy (Manual Therapy and Supervised Exercise14; EXERCISE) are routinely prescribed along with analgesics for both pain control and improved functioning. Both CBT and EXERCISE are behaviorally activating, improve self-efficacy, and reduce learned helplessness.15 These qualities make them rational choices for a prevention study of new episode MDD and anxiety disorders.

The order effect of these interventions on preventing MDD and anxiety disorders is also not known. Initial exposure to CBT may enhance attention to psychological health, motivation, and problem solving, thus enabling individuals who are first exposed to CBT to make better use of EXERCISE (compared with those exposed to EXERCISE followed by CBT). This order effect, however, is not established. Indeed, exposure to EXERCISE before CBT may engage participants who are otherwise not psychologically minded, preparing them to be more open to a psycho-behavioral intervention such as CBT. Since the clinical approach for non-responders to an intervention usually involves continued exposure or a switch, testing sequences of interventions is indicated to inform care.

Implementing and testing such complex interventions entails substantial methodological and logistic challenges; this is especially the case among older adults in whom individual variability is high and, often intervention tolerance may be low because of frailty or other geriatric-specific syndromes. Using a sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART)16 approach, we are attempting to address this set of unique methodological challenges as we seek to prevent new onset depression and anxiety in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. In order to guide future protocols, we describe here the trial methodology, intervention development, and procedural challenges and solutions experienced during the course of this study.

Methods

Overall Study Design and Specific Aims

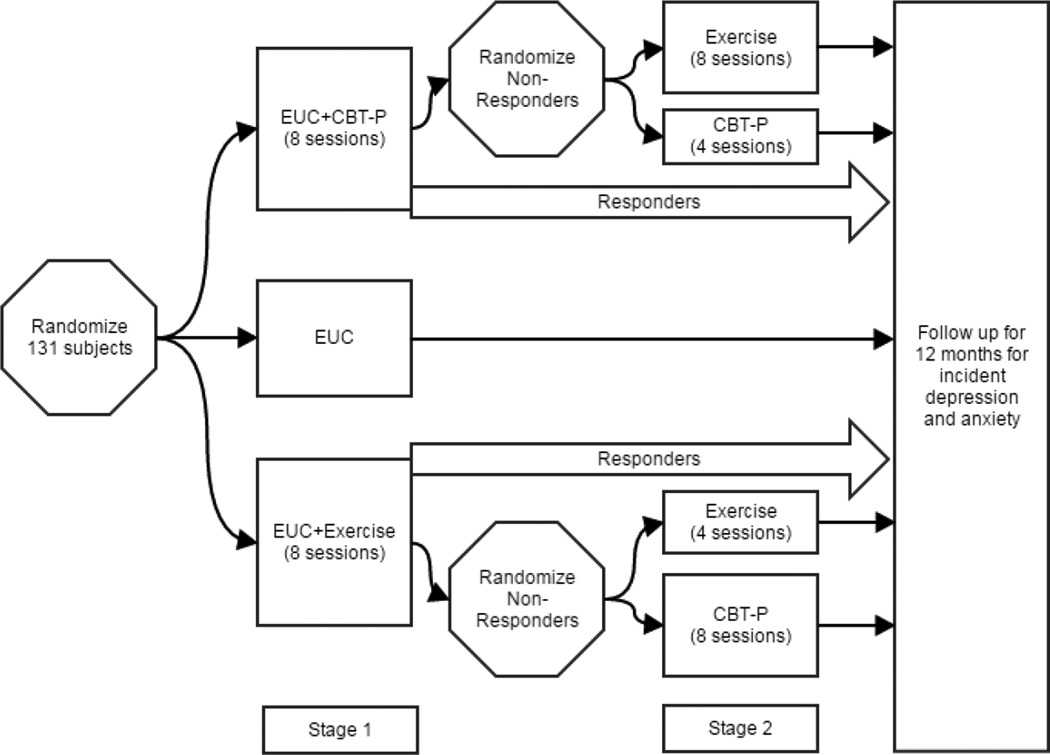

This is a two-stage adaptive treatment design project. Stage 1 compares the relative effectiveness of 8 sessions of CBT, 8 sessions of EXERCISE, and Enhanced Usual Care (EUC17,18; the control condition) (Figure 1). Non-responders to stage 1 then proceed to stage 2 in which they may be randomized to 8 sessions of the alternative intervention or 4 additional sessions of the intervention received during stage 1. All participants are then followed for 12 months after the end of their final intervention for new episodes of MDD and anxiety disorders. The overarching aims are to 1) develop a patient-centered new onset depression and anxiety prevention intervention for older adults living with knee osteoarthritis (CBT), 2) explore if improving pain and disability prevents new onset MDD and anxiety disorders during one-year follow-up among at-risk seniors with knee OA, and 3) permit an estimation of relative effectiveness of CBT, EXERCISE, and EUC as well as order-effects of the active prevention interventions. We also plan to follow participants receiving EUC to obtain benchmark estimates of new episode MDD and anxiety disorders.

Figure 1.

Study Design

CBT: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Pain

EUC: Enhanced Usual Care

Participants

Our target enrollment was 135 participants > 65 years old. While pain and associated disability are risks for depression, the majority of individuals living with these problems do not become depressed or anxious. This led us to a blended selective/indicated approach to depression and anxiety prevention by including individuals most at risk of new onset depression and anxiety disorders – those with subthreshold symptoms. Thus, in addition to having knee arthritis, participants also endorsed symptoms of subthreshold depression as determined by the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)19 scores of at least “1” (with one of the cardinal symptoms of depression [low mood or anhedonia] endorsed for at least several days for the past 2 weeks, and no diagnosis of current or partial remission MDD as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)20 interview). Participants could have a history of major depression and anxiety disorders, but not within the past 12 months. Including subjects with recent disorders would confuse the prevention of a new episode from the treatment of a partially remitted earlier episode.

Sources of recruitment include primary care, online, print, and radio advertisements, and university-affiliated research registries. After recruiting the first four participants for iterative development of CBT (see below), we began recruitment of the next 131 participants for Stage 1 of the adaptive prevention study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria and rationale for each entry criterion are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria and Rationale for These Decisions

| Inclusion Criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|

| ≥ age 60 | Prevention strategies (i.e., engagement and interventions) for older adults are different than for younger adults |

| Meets accepted clinical criteria for knee OA based on the American College of Rheumatology 1986 clinical criteria guidelines.28 |

We debated requiring radiographic evidence of knee osteoarthritis, but given that the clinical criteria (knee pain and 3 of the following: > 50 years old, < 30 minutes morning stiffness, crepitus on active motion, bony tenderness, bony enlargement, no palpable warmth of synovium) are what generate distress in patients (not abnormal radiographs), this approach to diagnosis seemed most relevant. |

| Western Ontario and McMaster University Arthritis Index (WOMAC) pain subscale score in the range of 7–15. |

A lower score of 7 includes participants with clinically relevant symptoms of knee OA. For example, a score of 7 could be a patient with either moderate to severe symptoms on one or two items, or someone who may be minimally to moderately impaired on each item. Higher scores suggest either moderate difficulty with all items or severe impairment on several items. Participants with scores > 15 may have symptoms so severe that CBT or EXERCISE may not provide substantial benefit. |

| PHQ-9 greater than 0, with at least one of the cardinal symptoms of depression (low mood or anhedonia) endorsed. |

Indicated prevention trials include individuals who are experiencing early or subthreshold symptoms of the condition of interest. We acknowledge that the majority of older adults with knee OA do not develop MDD or anxiety disorders. However, those with subthreshold depression, along with the knee OA, may be at increased risk of conversion to a syndromal depression or anxiety disorder. Requiring endorsement of depressed mood or anhedonia suggests that these participants may have a diathesis to a mood or anxiety disorder. |

| Modified Mini Mental State (3MS) Examination ≥>/= 80.30 |

Scores < 80 on the 3MS are highly suggestive of dementia. Scores ≥ 80 include participants with both normal cognition and mild cognitive impairment. To increase generalizability, we wanted to include participants with and without mild cognitive impairment. A prevention trial for individuals with dementia may require a different approach. |

| Has or is willing to establish care with a personal physician prior to any experimental procedures. |

Because participants may be randomized to EXERCISE, which includes aerobic conditioning as part of a home exercise program, for participant safety (in particular cardiac safety), we required permission of their primary care physician for participation. |

| Exclusion Criteria | |

| Episode of MDD within the past year. | As this is a study of indicated depression prevention, we did not want to enroll participants currently experiencing a partially treated episode of MDD. The lack of MDD within the past year was established by SCID. |

| Currently taking an antidepressant | Current use of antidepressant pharmacotherapy could prevent new onset MDD and anxiety disorders above any effect from CBT or EXERCISE. |

| Currently taking an anti-anxiety medicine > 4 times/week for the past 4 weeks. |

Sustained use of anti-anxiety medicine could prevent new onset anxiety disorders. |

| Lifetime history of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, or substance use disorder within the past 12 months. |

These individuals require treatments beyond the scope of a depression prevention project. |

| Receiving knee-related workers compensation or involved in knee pain-related litigation. |

Individuals involved with these kinds of litigation may experience secondary gain that could interfere with improvement. |

Interventions

Randomization and Sequence of Interventions

We use permuted block randomization with the list of consented participants maintained by the data manager. Participants are randomized using a 2:2:1 allocation (i.e., 2 participants randomized to either CBT or EXERCISE for every 1 subject randomized to EUC). As this is treatment development work, our reason for this allocation procedure is to gain more clinical experience with CBT and EXERCISE. Stage 1 for participants randomized to prevention interventions: Simultaneous to receiving EUC (which is provided for all participants, see below), participants are randomized to receive 8 weeks of either CBT or EXERCISE. Each session lasts 45–60 minutes. CBT is delivered at the PCP’s office, the offices of the Late-Life Depression Prevention Center, in the participant’s home, or via SKYPE or telephone. The location of where CBT is delivered is documented, as these data inform feasibility and scalability. EXERCISE is delivered at the Clinical and Translational Science Institute for Physical Therapy, a state-of-the art rehabilitation facility staffed with master’s and doctoral-level physical therapists. Stage 2: Stage 1 non-responders (defined below) are randomized to an additional 4 sessions of the same intervention or 8 sessions of the alternative intervention (Figure 1). This will allow us to explore if switching to a full dose of the alternative intervention or extending the current intervention is more efficacious for prevention. All participants, regardless of response status, are followed for 12 months for new onset MDD or anxiety disorder after completion of prevention interventions in Stage 1 or Stage 2, or for those randomized to EUC alone.

Enhanced Usual Care (EUC)

All participants, including those randomized to EUC, have information mailed to their PCP describing the best practice approach for providing analgesia for knee osteoarthritis.21 For all participants, incidental findings during scheduled blinded assessments (i.e., new onset depression or anxiety or worsened pain or cognition) are relayed to their PCP. We acknowledge that while the choice and dosing of analgesics are not standardized, this approach reflects the array of medication regimens required for analgesia and provided in primary care, and is consistent with a collaborative care approach.22 We track the type and dosage of both scheduled and as-needed medications (opioids and non-opioids) and other somatic interventions (e.g., acupuncture, injections).

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Pain (CBT)

Training the Interventionists

Clinicians experienced in providing manualized psychotherapy to older adults (supervised weekly by JQM) provide CBT. The intervention modules are: 1) combating demoralization; 2) teaching coping skills and problem solving techniques; 3) shifting self-view to that of an active, resourceful, and competent person and encouraging behavioral activation; 4) learning to alter associations between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that do not promote analgesia and identifying how to change automatic, maladaptive thoughts; 5) learning relaxation skills; and 6) facilitating maintenance and generalization of skills. As insomnia is prevalent in older adults and those with pain, a modified version of Brief Behavioral Treatment of Insomnia (BBTI)23 is included if participants score > 5 on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) at baseline.24 The inclusion of modified BBTI has not increased the number of sessions or exposure to CBT. Participants can decide to focus on BBTI instead of one of the other modules, in the spirit of a personalized intervention. All CBT sessions are audiotaped and 20% then randomly selected for fidelity ratings by JQM to assure maintenance of treatment specificity and integrity.

Adapting and Revising the Intervention

To ensure intervention fidelity, we use group supervision and one-on-one feedback using evaluations of randomly selected 20% of audiotapes of CBT sessions. CBT adherence ratings assessing quality are completed by the intervention supervisor, using two sessions for each case — an early session (1–3) and a later session (4–8). Following a batch of ratings, corrective feedback is provided. We also developed a treatment fidelity scale to document the absence of intervention contamination effects. Using this scale, ratings are completed on seven consecutive minutes of the session starting five minutes into the session. Sessions are rated independently by two raters for the presence of CBT elements.

The content and ordering of the modules, components of the manual, and appearance and content of participant handouts were all reviewed and modified on a weekly basis over the course of the first 3 months of the project. Since this is an intervention development project, we assumed there would continue to be adjustments to the intervention as we continued to elicit feedback from the participants and clinicians. Indeed, during the course of the project, adjustments to CBT have been made to account for degrees of cognitive impairment, difficulty with movement, insomnia, and transportation. The principles of each module were articulated to the participants. Also, we developed graphics to communicate the content of and connections between modules and the gate control theory of pain26 as well as the proposed mechanism via which each module may reduce pain and stress and improve functioning.

EXERCISE

The EXERCISE intervention is a combination of supervised exercise therapy and manual therapy techniques. The supervised exercise component represents state-of-the-art evidence-based practice guidelines14,27,28 and combines aerobic and strengthening exercises.14,27,28 The manual therapy techniques involve the application of manual force from the therapist.29 These techniques include a series of motions of the tibia with respect to the femur that are needed for normal knee flexion and extension. The manual therapy techniques also include lower extremity stretching exercises delivered by the therapist. Detailed descriptions of the manual therapy techniques and intervention philosophy utilized in this study are available in manual therapy textbooks.30 In addition, all participants are instructed in a home exercise program with the goal to be independent in the home exercise program by week 8.

Schedule of Assessments, Criteria for Response and Booster Sessions

Independent evaluators assess participants by phone or in person. Participants are assessed at six time points (T1-T6) (Table 2). We defined clinically significant response to the active interventions (unique from the primary aim of prevention of MDD and anxiety disorders as diagnosed with the blended PRIME-MD/MINI Neuropsychiatric interview) as 1) much better or 2) very much better on a Patient Global Impression of Change (P-GIC) that ranged from 1–7. The wording of the P-GIC is: “Check the circle that best describes how you have felt overall since you began participating in this research study.” We selected the P-GIC as criteria for response because since participants endorsed both knee pain and mild emotional distress, only using percent improvement of pain as the response criterion could miss other improvements valued by participants, such as improvement in insomnia, psychological stress, or self-efficacy. Pain, stiffness, depression, anxiety, and the Western Ontario and McMaster University Arthritis Index are also assessed at these time points. We plan to calculate degree of correlation between the P-GIC and each of these measures to learn more about whether these variables change in concordant directions.

Table 2.

Baseline and Follow-up Assessments (T1 – T6): Self-report or blinded Independent Assessors

| Domain | Measure |

|---|---|

| Psychiatric Diagnosis | SCID at baseline, MINI/PRIME-MD at every three months in follow-up (Note: The MINI/PRIME-MD is used to assess syndromal depression and anxiety disorders at every follow-up). |

| Knee Osteoarthritis Diagnosis | American College of Rheumatology clinical criteria for knee osteoarthritis at baseline |

| Depression severity | Patient Health Questionnare-9 (PHQ-9)* |

| Anxiety | Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)* |

| Medical burden/Medication Check List/Vitals |

Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS-G)** Cornell Service Index* Medication List Update* Vitals (Weight, Blood pressure, Hip and Waist Circumference, History of Falls)** Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C)* |

| Disability | Late-Life Functional Disability Inventory (LL-FDI) * |

| Functional status, physical performance | Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) ** |

| Insomnia | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)* |

| Overall Body Pain | Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS-20)* |

| Knee Pain and Disability | Western Ontario and McMaster University Arthritis Index (WOMAC)* Patient Global Assessment of Functioning* Patient Global Assessment of Pain Severity* Catastrophizing Subscale of the Coping Strategies Questionnaire** |

| Cognitive Status | Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status** Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System** Modified Mini Mental State Examination at baseline |

| Social Isolation/Support | Interpersonal Support Evaluation List* |

| Problem Solving Skills | Social Problem Solving Inventory (SPSI)** |

| Biosignatures | Inflammatory Cytokines* (IL6, TNF alpha) + mRNA Transcription (blood draw)* Genetic data only collected at T1 |

| Global Health | Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC)* RAND-12* Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE)* |

| Satisfaction | 5 questions to rate satisfaction plus comment field administered at study Completion |

Baseline and every three months in follow-up

Baseline and every six months in follow-up

Responders to Stages 1 and 2 are followed for 12 months (from the end of the intervention) for conversion to new onset MDD or anxiety disorder. Based on work by Rovner,31 responders receive booster sessions at 6 and 9 months following the end of the prevention intervention(s). If participants receive both interventions, then they can select the booster session they prefer. Stage 2 non-responders are referred to their PCP with pain treatment recommendations (based on expert guidelines). Non-responders are also followed for 12 months for the development of new onset MDD or anxiety disorder.

Planned analysis

Cox regression models will be used to assess whether study groups differ reliably on risk of the outcome events (MDD and anxiety disorders), adjusting for participant characteristics as needed. We also plan to estimate the number needed to prevent, with a 95% confidence interval, comparing CBT, EXERCISE, and controls who received EUC. Since the actual number of “events” (e.g., incident syndromal depression or anxiety) may be few, we will also explore changes in symptoms severity, using continuous measures of depression and anxiety. To assess a difference in reduction in pain, we will use Kaplan-Meier methods to report the estimated percentage of participants achieving the endpoint over time, defined as at least a 30% improvement on the pain subscale of the WOMAC. The log-rank test will be used to test the primary event across the three groups (CBT-P, EXERCISE, and EUC).

Considering that we are using SMART methodology,16 we will also use statistical methods for dynamic treatment regime (also known as adaptive treatment strategy) to compare sequenced interventions. Specifically, we will estimate the effect of treatment sequence “Treat with CBT-P for 8 weeks, if does not respond, use EXERCISE intervention” in reducing pain compared to other sequences. For these comparisons, we will use inverse-probability-weighting and g-estimation.33,34

Early Results

Recruitment

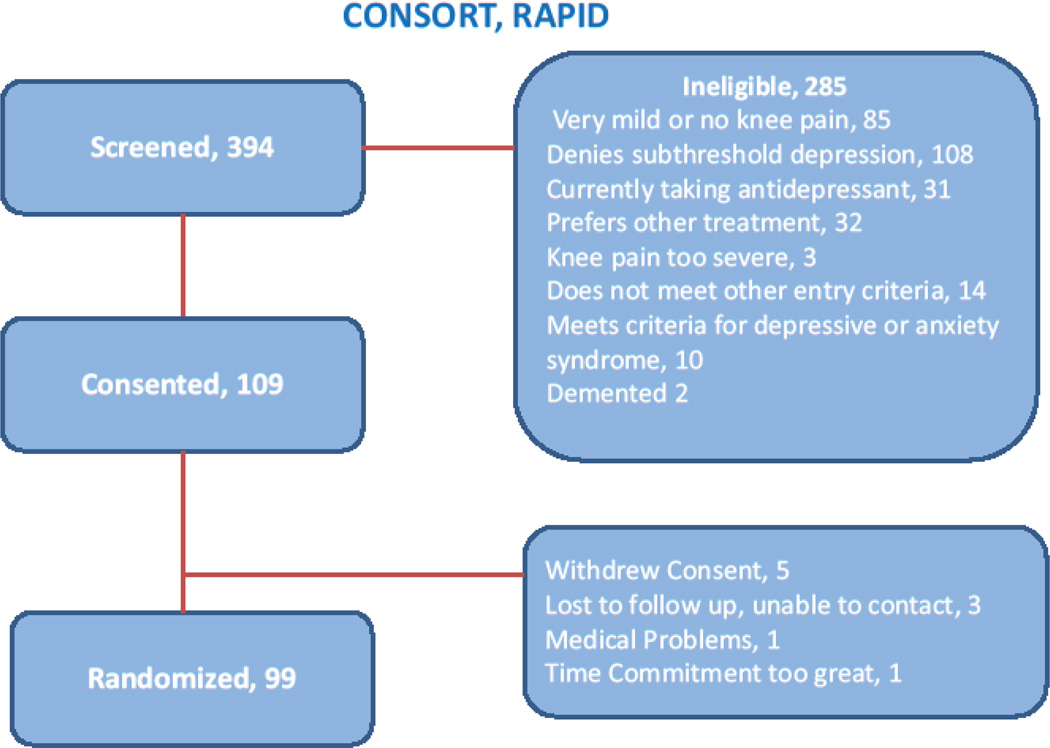

As of December 2014, we have recruited 73% (n=99) of our expected sample (Figure 2). Because of a delayed start, the need for 12 months of follow-up, and the fact that this is a treatment development and not efficacy testing experiment, we halted recruitment at this time. Forty-seven percent of screened participants have been recruited from direct-to- consumer advertisements (radio, newspaper, and advertisements on public transportation), university-affiliated late-life research registry (32%), primary care (8%), and other sources (13%). These sources of recruitment are different from our recently completed depression prevention study of older adults living with high emotional stress in which 45% were recruited from primary care and approximately 20% were recruited from community outreach endeavors.35 The percentage of individuals who phoned in and were screened over the phone found to be ineligible for further evaluation was 74%. The primary reasons for ineligibility were knee pain not severe enough (28%), items 1 or 2 on the PHQ-9 (depressed mood or anhedonia) not endorsed (21%), PHQ-9 score = 0 (18%), and currently taking an antidepressant and not willing to discontinue it (11%). Table 3 lists descriptive characteristics of participants at baseline.

Figure 2.

Consort Diagram

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics (n = 99)

| Variable | Descriptive Statistic |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71.0 (7.6) |

| % Female | 61.6 (n=61) |

| % European American | 81.8 (n=81) |

| Education (years) | 14.9 (2.6) |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 31.7 (8.8) |

| Cumulative Illness Rating Scale: Total (range = 0–52, higher = worse) | 8.6 (3.4) |

| Cumulative Illness Rating Scale: Count (range = 0–13, higher = worse) | 5.6 (2.1) |

| RAND12 Mental Health Component (t score: mean = 50; SD = 10, higher is better) |

47.7 (8.3) |

| RAND12 Physical Health Component (t score: mean = 50, SD = 10; higher = better) |

34.6 (7.3) |

| Short Physical Performance Battery (range 0–12; higher = better) | 9.0 (2.5) |

| Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) pain subscale (range 0–20, higher = worse) |

9.1 (2.0) |

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (range 0–27, higher = more depression) |

5.6 (2.1) |

| Generalized Anxiety Questionnaire (GAD7) (range 0–21; higher = more anxiety) |

3.2 (2.7) |

| Interpersonal Support Evaluation List – modified 12 item (range 0–48; higher = more supports) |

40.4 (5.6) |

Participant Satisfaction

Following T6 (12 months), participants are asked to complete a brief satisfaction survey. The survey questions, rated on a scale from highly dissatisfied to highly satisfied, were created to inform the success of future studies by assuring the interventions are patient-centered and that participants are satisfied with: 1) flexibility in scheduling appointments; 2) helpfulness of the therapist; 3) frequency of appointments; 4) usefulness in managing pain; and 5) usefulness in managing stress. The survey also includes a free text box where participants can share their thoughts about how the project can be improved. Table 4 summarizes these data to date.

Table 4.

Satisfaction Survey Results of 46 Participants Who Exited the Study After 1 Year of Participation.

| Flexibility in scheduling study appointments |

Helpfulness of the therapist |

Frequency of appointments |

Usefulness in managing pain |

Usefulness in managing stress |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average score (SD)* |

3.9 (0.4) | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.5 (0.7) | 3.2 (1.0) | 3.3 (1.0) |

Theoretical range: 1 (highly dissatisfied) – 4 (highly satisfied)

While in general the responses were positive, the results indicated there may be room for improvement in management of pain. However, the average score ranged between satisfied to highly satisfied, and given the challenge of treating chronic pain, this is encouraging. The free text responses suggest varying degrees of satisfaction with the project. We have used these responses to: 1) be more direct about the mental illness prevention goals of the study, since at least one subject felt we were using knee pain as a “hook” to enroll participants; and 2) during the consent process, more explicitly describe how we think CBT may help with both pain control and prevention of both MDD and anxiety disorders.

Lessons Learned and Adjustments Made During the Course of the Project

Since this prevention intervention development project is a blend of public health (prevention of depression) and clinical care (improving knee pain and disability) and is being conducted in preparation for a confirmatory R01, we expected that many changes to the protocol would be required during the project. Table 5 lists the many challenges to the successful implementation and completion of the protocol and how we resolved these challenges without compromising internal validity. Our multidisciplinary team meets on a weekly basis during which methodological and procedural issues from ongoing trials are discussed. Solutions to challenges are discussed among the staff (who usually bring the challenges to the meeting), the principal investigator, and biostatistician. Using this approach we address the feasibility and burden concerns of staff while assuring the specific aims of the PI are being met and that any adjustments to the protocol will not interfere with the analytic plan. Many of the challenges described in Table 5 can be categorized as: 1) minimizing subject burden; 2) optimizing retention and minimizing early attrition; 3) minimizing missing data and adding assessments; 4) adjusting time frames during which data may be collected; 5) assuring participant safety; and 6) addressing threats to internal validity of the study such as assuring entry criteria are met before randomization.

Table 5.

Methodological Challenges Experienced During the Study and Solutions

| PROBLEM or CHALLENGE | SOLUTION |

|---|---|

| Subject burden. |

|

| 10/18/11 Unclear randomization procedure. |

|

| Timing of booster sessions |

|

|

2–10–12 First participant consented and randomized. | |

| Clinical and research management of participants who become syndromal |

If a subject develops MDD or anxiety disorder they will exit the intervention but continue in follow-up. |

| Timing of initiation of follow-up phase |

|

| Unclear description about depression symptoms and treatment history at entry into study |

|

| Assessment of outcomes of interest |

|

| Capture of serious adverse event data. Reminder about anxiety disorders as outcome of interest. Missing items. |

|

| Measuring participant engagement |

|

| Low rates of serial blood draws for biomarkers |

|

| Retention during follow-up |

|

| Collection of nutritional supplement data. |

|

| Management of participants who start an antidepressant during participation. |

|

| Emerging concerns about participant burden |

|

| Management of drop-outs. |

|

| Window of time allowed for collection of follow-up data. |

|

| Assurance that entry criteria have been met prior to randomization |

|

| Further evaluation of alcohol misuse |

|

| Management of delay between screening and baseline. |

|

| Management of participants randomized but who never received any intervention. |

|

Discussion

Two unique qualities of this depression prevention project deserve highlighting. First, this may be the only study of depression prevention to utilize formal SMART methodology. Such trials are individually tailored interventions that specify how the intensity or type of treatment should change depending on the participant’s needs. For example, this project will guide our understanding of how such interventions for prevention of depression and anxiety disorders can: 1) Adapt treatment to a patient’s chronic and/or changing course; 2) Deliver appropriate treatment when needed most; 3) React to non-adherence or side-effect profiles; 4) Reduce treatment burden and deliver only what is necessary; 5) Deliver early treatments with positive and durable downstream prevention effects; and 6) Sift through available treatment options.16 This may lead to more personalized prevention care over time.

The second characteristic which distinguishes this prevention project from others is the utilization of a unique multidisciplinary team approach. Our clinical research group is comprised of geriatric psychiatrists and other types of clinical mental health professionals, physical and occupational therapists, a geriatrician, an epidemiologist, an expert in community behavioral health, biostatisticians, and a geropsychologist. Given the complex etiology and natural history of depression and anxiety disorders, a team with expertise in these varied disciplines is needed to guide effective prevention efforts. Unlike other depression prevention work in at-risk older adult populations such as post-stroke36, macular degeneration37, and high psychological stress35 all of which focused on improving problem solving skills, our project compared a behaviorally activating but non-psychological intervention (EXERCISE) with a pain-specific psychosocial intervention (CBT). This type of work, which may have greater generalizability and acceptability by a subsample of our at-risk group, can only be done well with expertise from relevant disciplines.

A lesson learned in this treatment development trial is that older adults with knee arthritis and subsyndromal depression are interested in efforts to maintain their independence and improve their mental health. Engaging patients in an intervention that may both treat a nuisance condition (like pain) but also has mental health-promoting qualities (like CBT and EXERCISE) appears to be an efficient approach to optimizing both physical and mental health. A related lesson learned from this project with relevance for the field of prevention research is where and how participants may be most efficiently recruited. Unlike many of our treatment trials in which we rely heavily of community-based primary care physicians to refer symptomatic patients, in this prevention trial our recruitment succeeded because of direct-to-consumer advertising. Given the challenges of recruitment for all types of studies (both treatment and prevention), effective implementation of recruitment initiatives early on in the trial is critical for achieving recruitment milestones.

Perhaps the greatest limitation to our project is the fact that follow-up is limited to one year. Our study follows participants for a similar length of time as most other prevention protocols. For example, a recent meta-analysis of 32 randomized controlled trials examining the effects of preventive interventions in participants without diagnosed depression described a 21% decrease in incidence over 1–2 years in prevention groups compared to control groups.38 This is a substantial reduction in incidence, and the field is now poised to assess participants for longer periods of follow-up. This is important, because in a three year observational study of incident depression, Schoevers et al described that in older adults, subsyndromal symptoms of depression were associated with a risk of almost 40% of developing a depressive episode.39 Pending the results of this protocol, in our next depression and anxiety prevention program, we plan to monitor participants for at least 3 years.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jacqueline Stack, MS for study coordination and Amy E. Begley, MS for data analyses.

Funding: This study was funded by NIH P30 MH090333, AG033575, UL1RR024153 and UL1TR000005.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: Receipt of medication supplies for investigator-initiated studies from Pfizer and Reckitt Benckiser. Dr. Butters served as a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline from whom she received remuneration for participating in cognitive diagnostic consensus conferences for a clinical trial; the remaining authors report no disclosures.

References

- 1.DeVellis BM. Depression in rheumatological diseases. Baillieres Clinical Rheumatology. 1993;7(2):241–257. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3579(05)80088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and Pain Comorbidity: A Literature Review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(20):2433–2445. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Docking RE, Fleming J, Brayne C, et al. Epidemiology of back pain in older adults: prevalence and risk factors for back pain onset. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011 Sep;50(9):1645–1653. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnow BA, Hunkeler EM, Blasey CM, et al. Comorbid depression, chronic pain, and disability in primary care. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68(2):262–268. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000204851.15499.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bittner A, Goodwin RD, Wittchen HU, Beesdo K, Hofler M, Lieb R. What characteristics of primary anxiety disorders predict subsequent major depressive disorder? J Clin Psychiatry. 2004 May;65(5):618–626. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0505. quiz 730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karp J, Reynolds C. Depression, pain, and aging. FOCUS. 2009;7:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchtemann D, Luppa M, Bramesfeld A, Riedel-Heller S. Incidence of late-life depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012 Dec 15;142(1–3):172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meller I, Fichter MM, Schroppel H. Incidence of depression in octo- and nonagenerians: results of an epidemiological follow-up community study. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience. 1996;246(2):93–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02274899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2003 Mar;58(3):249–265. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.m249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luppa M, Sikorski C, Luck T, et al. Age- and gender-specific prevalence of depression in latest-life--systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2012 Feb;136(3):212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryant C, Jackson H, Ames D. The prevalence of anxiety in older adults: methodological issues and a review of the literature. J Affect Disord. 2008 Aug;109(3):233–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Beurs E, Beekman AT, van Balkom AJ, Deeg DJ, van Dyck R, van Tilburg W. Consequences of anxiety in older persons: its effect on disability, well-being and use of health services. Psychol Med. 1999 May;29(3):583–593. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reid MC, Otis J, Barry LC, Kerns RD. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic low back pain in older persons: a preliminary study. Pain Medicine. 2003;4(3):223–230. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deyle GD, Henderson NE, Matekel RL, Ryder MG, Garber MB, Allison SC. Effectiveness of manual physical therapy and exercise in osteoarthritis of the knee. A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2000;132(3):173–181. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-3-200002010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seligman ME. Learned helplessness. Annual review of medicine. 1972;23:407–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.23.020172.002203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy SA. An experimental design for the development of adaptive treatment strategies. Statistics in Medicine. 2005;24(10):1455–1481. doi: 10.1002/sim.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unutzer J, Hantke M, Powers D, et al. Care management for depression and osteoarthritis pain in older primary care patients: a pilot study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;23(11):1166–1171. doi: 10.1002/gps.2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.AGS Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(8):1331–1346. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dobscha SK, Corson K, Perrin NA, et al. Collaborative Care for Chronic Pain in Primary Care: A Cluster Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2009 Mar 25;301(12):1242–1252. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.377. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Germain A, Shear MK, Hall M, Buysse DJ. Effects of a brief behavioral treatment for PTSD-related sleep disturbances: a pilot study. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 2007;45(3):627–632. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerns RD, Otis JD, Marcus KS. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain in the elderly. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2001;17(3):503–523. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(05)70083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melzack R, Wall P. Pain mechanisms: A new theory. Science. 1965;150:971–979. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3699.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deyle GD, Allison SC, Matekel RL, et al. Physical therapy treatment effectiveness for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized comparison of supervised clinical exercise and manual therapy procedures versus a home exercise program. Physical Therapy. 2005;85(12):1301–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ottawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for therapeutic exercises and manual therapy in the management of osteoarthritis. Physical Therapy. 2005;85(9):907–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moss P, Sluka K, Wright A. The initial effects of knee joint mobilization on osteoarthritic hyperalgesia. Manual Therapy. 2007;12(2):109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maitland G. Peripheral Manipulation. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rovner B, Casten R. Preventing late-life depression in age-related macular degeneration. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16(6):454–459. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31816b7342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1979;47(2):343–352. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bembom O, van der Laan MJ. Statistical methods for analyzing sequentially randomized trials. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2007 Nov 7;99(21):1577–1582. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ko JH, Wahed AS. Up-front versus sequential randomizations for inference on adaptive treatment strategies. Stat Med. 2012 Apr 30;31(9):812–830. doi: 10.1002/sim.4473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Thomas SB, Morse JQ, et al. Early intervention to preempt major depression among older black and white adults. Psychiatr Serv. 2014 Jun 1;65(6):765–773. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson RG, Jorge RE, Moser DJ, et al. Escitalopram and problem-solving therapy for prevention of poststroke depression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008 May 28;299(20):2391–2400. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.20.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rovner BW, Casten RJ, Hegel MT, et al. Low Vision Depression Prevention Trial in Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Ophthalmology. 2014 Jun 25; doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Zoonen K, Buntrock C, Ebert DD, et al. Preventing the onset of major depressive disorder: a meta-analytic review of psychological interventions. Int J Epidemiol. 2014 Apr;43(2):318–329. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schoevers RA, Smit F, Deeg DJ, et al. Prevention of late-life depression in primary care: do we know where to begin? Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Sep;163(9):1611–1621. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998 Sep 14;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]