Summary

Matched case-control studies are popular designs used in epidemiology for assessing the effects of exposures on binary traits. Modern studies increasingly enjoy the ability to examine a large number of exposures in a comprehensive manner. However, several risk factors often tend to be related in a non-trivial way, undermining efforts to identify the risk factors using standard analytic methods due to inflated type I errors and possible masking of effects. Epidemiologists often use data reduction techniques by grouping the prognostic factors using a thematic approach, with themes deriving from biological considerations. We propose shrinkage type estimators based on Bayesian penalization methods to estimate the effects of the risk factors using these themes. The properties of the estimators are examined using extensive simulations. The methodology is illustrated using data from a matched case-control study of polychlorinflated biphenyls in relation to the etiology of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Keywords: Bayesian lasso, Bayesian ridge, Empirical Bayes, Hierarchical Bayes, Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Two-stage lasso

1. Introduction

Nested or matched case-control studies are popular cohort designs used to assess the effect of exposure(s) in epidemiologic applications. By selecting a subset of the available controls that are ’close’ match to the cases in confounding characteristics, nested case-control studies can provide significant savings in resources while presenting results that are less biased than the traditional all-comers analysis. In some situations, the number of exposures of interest is small, such as family history, smoking status etc. in a study of incidence of certain type of cancers. Often, however, we have multiple exposures that are also potentially related in a non-trivial manner. Such exposures can arise as a collection of single item responses about lifestyle from a large survey questionnaire, as presence/absence of genes in a discovery framework, or as a combinflation of environmental and genetic risk factors (Witte et al. 1994, Satagopan et al. 2011). Modern epidemiologic studies increasingly rely on biological pathway information to express the collective effect of exposures (Thomas 2005). Regression analysis using individual exposure variables can result in inflated Type I error and possible masking of effects due to correlation between exposures (Robins and Greenland 1986). Data reduction methods such as principal components analysis, multidimensional scaling, latent class modeling etc. are used to group several similar variables. These exploratory methods, however, are entirely data-driven, and are frequently not replicated in a new wave of samples. Often, thus epidemiologists and clinical investigators rely on prognostic factors grouped using a thematic approach, with themes deriving from biological considerations (Thomas 2005). This is the premise of our current investigation.

Consider a 1:1 matched case-control study comprising of N matched strata. Indexing the subjects in the i-th stratum as i1 and i2, let the odds of them being a case be oddsi1 and oddsi2, respectively. The conditional log-likelihood contribution of the i-th stratum is then

| (1) |

where δi1 = 1 or 0 according as subject i1 is a case or a control. The usual logit formulation

translates (1) to the familiar expression

| (2) |

where δi2 = 1−δi1, β = (β1, …, βp)′ is the vector of regression coefficients, and (Xi1,1, …, Xip,1)′, (Xi1,2, …, Xip,2)′ are the collection of co-variates corresponding to the case and the control, respectively (Breslow et al. 1978). The regression parameters β can be estimated through standard p-variable maximization of the log-likelihood . The ensemble of covariates X will typically contain the exposures of interest as well as the potential confounders. For simplicity of exposition, we shall assume the absence of confounders. The thematic dimension-reduction approach consists of applying a linear transformation

| (3) |

where W is a p × K matrix of known constants; typically K is considerably smaller than p. The K × 1 association parameter vector γ in the reduced model corresponds to X through the equation

| (4) |

To distinguish (4) from the full model parameters, we shall refer to the association parameters in (2) as βfull henceforth. The method here is akin to the classic reduced rank regression technique that has been popularized by Anderson (1951), and has been used in the contexts of multivariate linear regression (Reinsel and Velu 1998), generalized linear models (Yee and Hastie 2003) and survival models (Fiocco, Putter, and van Houwelingen 2005) among others. In the presence of possibly collinear prognostic factors, reduced rank regression offers a parsimonious and efficient alternative.

The investigation in the current article is motivated by a matched case-control study of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). Polychlorinflated biphenyls (PCBs) have received attention as a risk factor for NHL due to their ubiquitous presence in the environment and widespread exposure to these chemicals by the general population in industrialized countries (Engel et al. 2007). PCBs exhibit a variety of biological activities and many have long biological half-lives. Hence, their adverse effect on health, particularly NHL, is of great concern. In this paper, we consider data on thirty six PCB congeners available from the Janus cohort of the Cancer Registry of Norway (Engel et al. 2007). Our interest is on the association between disease status and serum concentrations of these congeners. In order to avoid potential inflation in Type I error or loss of power that may be induced by evaluating all congeners individually, we consider Wolff’s system for grouping the congeners into four categories based on their known or anticipated biological activities (Wolff et al. 1997). The effect on the bias and precision of the estimates resulting from such reduction is the focus of our study.

The properties of reduced rank estimates are intimately connected to W. A smaller K (number of columns of W) imposes greater degree of clustering and consequently less exibility on the association coefficients. For example, when K = 1, βred is simply a constant multiple of W. Thus a weight matrix W that is too coarse in grouping the exposure variables can result in inflated false positive findings and biased conclusions. The gain in precision associated with the approach can be severely offset by this bias. The primary objective of the present investigation is to exploit the bias-variance trade-off between the full and reduced model maximum likelihood estimates (MLEs) to construct estimators with improved performance.

In Section 2, we employ an empirical Bayes type shrinkage to construct estimators that provide an improvement over the traditional full model MLEs. Section 3 contrasts this approach with a Bayesian penalization approach in the presence of multiple and potentially collinear predictors. In Section 4, we implement the prescribed methodology to the Janus NHL data to obtain insights into the properties of these methods in a real data setting. Section 5 presents a simulation study to examine the properties of the various methods. The investigation is concluded in Section 6 with some summary remarks.

2. Empirical Bayes Approach

Empirical Bayes (EB) is a popular frequentist approach dating back to the early work by Robbins (1955) that borrows strength from the Bayesian paradigm to provide improved inference. The parametric version of EB, adopted in the current article, was popularized through a series of articles by Efron and Morris (1971, 1972). Despite some of its shortcomings noted in the literature, the EB approach remains a popular inferential tool for statisticians to date.

In this section, we present a parametric EB type approach to assess the association with the exposure variables. The idea is to borrow strength from the full and the reduced model estimators, both of which have merits of their own. Henceforth, we shall denote the full model MLEs based on (2) by β̂full. The reduced model MLEs are obtained by computing the MLE’s γ̂ first and subsequently using (4) to yield

| (5) |

When W is the identity matrix, we should have βfull = βred. In general, the difference r = βfull − βred is a nonzero quantity. This motivates an alternative expression for βfull, denoted βB, as:

| (6) |

that can be estimated by plugging in βred from (5) along with an estimate of r. Note first that the MLE of r is simply r̂ = β̂full − β̂red. The approximate sampling distribution of r̂ can be specified as r̂ | r ~ N(r, Σ), where Σ is the asymptotic variance-covariance matrix of r̂. In order to follow the EB path, we assume a prior distribution of r as r ~ N(0, A). Consequently the posterior distribution of r is r | r̂ ~ N (A(Σ + A)−1r̂, (Σ−1 + A−1)−1). A Bayes estimator of β under squared error loss is then given by

| (7) |

The weighted version in (7) demonstrates that the shrinkage of the Bayes estimator towards β̂full or β̂red depends on the relative magnitudes of the variance-covariance matrices Σ and A. A relatively dominant Σ compared to A implies a less precise r̂. In that case βB is pulled more towards the reduced model estimator. The reverse happens when the relative contribution of the prior variability A is larger in the total variability of the marginal distribution of r̂. Equation (7) can be re-expressed as

| (8) |

Since marginally, r̂ ~ N(0, Σ + A), we may estimate R ≡ (Σ + A) in (8) by its sample counterpart r̂r̂′. This, however, may lead to the undesirable situation where the estimator of A = R − Σ is not non-negative definite. On the other hand, imposing the constraint of non-negative definiteness on the estimator of R − Σ in general would lead to cumbersome and un-intuitive conditions. Instead we adopt the conservative approach of estimating A by

| (9) |

which ensures non-negativity. This is the multivariate analog of the strategy adopted by Mukherjee and Chatterjee (2008) where the authors focus on the univariate gene-environment interaction parameter for a case-control study. In fixed-effects linear regression model with independent, homoscedastic error structure, the choice of (9) as the empirical estimator of A gives rise to the optimal shrinkage estimator of β in the class

where M is a p × p matrix that minimizes the expected squared error loss (Satagopan et al. 2011). A crucial observation in the linear regression case is that the representation β̂full = β̂red + r̂ provides an orthogonal decomposition, a phenomenon that does not carry over to the matched case-control framework. Nonetheless, we use Equation (9) as an EB version of A. Another EB estimator is obtained by setting A = τ2Ip, with Ip being the p × p identity matrix. This is tantamount to assuming that the components of r constitute a sequence of independent and identically distributed random variables. The estimated A is given by

| (10) |

We need to also estimate Σ in order to compute the EB estimate of β in (7). Now

| (11) |

We demonstrate in the Web Appendix the steps to estimate the terms in (11). Equations (9) and (10), along with the estimated Σ generates the corresponding EB estimators for βfull.

In order to assess any possible improvement in efficiency over the MLEs, one needs to estimate the sampling variability of the EB estimators. Using standard large-sample theory, the asymptotic normality of the EB estimators follow from the joint normality of (β̂full, β̂red). In view of (7), the large-sample variance depends on Σ which is a non-trivial function of both β̂full and β̂red. The derivation of the variance of β̂B is consequently cumbersome, and does not lend to any easy approximation. For our applications in this article, we shall estimate the variance and the confidence intervals for the components of β̂B using the bias corrected bootstrap (BCa) approach (Efron and Tibshirani 1993).

3. Bayesian Approach

The EB procedure in the previous section has its roots in a Bayes-type shrinkage argument. In this section, we present a hierarchical Bayesian approach to the estimation problem. Noting that our motivating example consists of multiple exposures that are possibly related to each other, we present a Bayesian framework that mimics the penalization approach. Stemming from the original work by Tibshirani (1996), Park and Casella (2008) and Hans (2009) independently advanced the Bayesian version of lasso (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator), a method that generates L1-penalized least squares estimates. Although studied primarily in linear models, there has been limited use of Bayesian Lasso in other contexts such as binary probit regression (Bae and Mallick 2004). We propose two different lasso approaches under the Bayesian framework, each motivated from a different objective.

3.1 Two-Stage Lasso Regression

Traditionally lasso and other related penalization methods focus on variable selection from a large collection of predictors. Here we adopt a modification of the Bayesian lasso, noting that one of our primary objectives is to shrink the difference between the full and reduced model parameters towards zero. In the first stage, we obtain β̂red, the MLEs of βred based on (4). In the second stage βfull is estimated via the L1-penalized objective function

| (12) |

where l(βfull) is the log-likelihood of the matched case-control data re-expressed to emphasize its dependence on βfull, while βs and β̂red,s are the s-th components of βfull and β̂red, respectively, and θ > 0 is a penalty parameter. The criterion in (12) can be recast in a Bayesian mould in the following way. Consider the hierarchical prior specification:

βs | β̂red,s, θ, σ2, ; σ2 > 0, τs > 0 independently for each s = 1, …, p.

- τs | θ are i.i.d. Rayleigh(θ2) with probability density function

- θ2 has a Gamma(a, b) distribution with probability density function

σ2 has an inverse-Gamma distribution parameterized by c1 and c2.

Integrating out (i) with respect to (ii) yields the conditional Laplace prior

which, along with l(βfull), results in (12) apart from the multiplier σ. The formulation is analogous to Park and Casella (2008) in the context of linear models. Unlike the linear model application however, the scale parameter σ2 here is a prior parameter. In that sense the approach adopted here can be thought of as a hierarchical Bayesian procedure. Note that the two-stage procedure does not constitute a proper Bayesian analysis as it is conditional on running a first stage reduced rank model to obtain β̂red. Yet this is consistent with our main objective of leveraging information from the reduced dimension model.

Full Conditional Distributions

The parameters of interest βfull and the variances can be estimated via posterior simulation. While the posterior distributions are not in standard form, the particular choice of priors yield tractable full conditional distributions for most parameters and can easily be embedded in a standard Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) setup (Gilks 2005). Below we indicate the full conditional distribution of all relevant parameters. Details of the derivation are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

β: The full conditional distribution of βj can be shown to be log-concave, and can be sampled from using Metropolis Hastings algorithm quite efficiently.

-

: The full conditional distribution of is inverse-Gaussian with parameters

Further, are distributed independently of each other.

θ2: The full conditional distribution of θ2 is .

σ2: The full conditional distribution of σ2 is inverse-Gamma with parameters shape = c1 + p/2 and , where Dτ is the p × p diagonal matrix with , s = 1, …, p as the diagonal entries.

3.2 Bayesian Lasso Regression

The two-stage lasso, which is a hybrid of frequentist and Bayesian approaches, can be thought of as a variant of the EB. A more formal Bayesian analysis can be carried out by using a prior formulation that does not rely on β̂red. Consider the hierarchical prior specification for βfull:

Conditionally βs | γ, θ, σ2,, and

γ | σ2 ~ N(0, σ2IK),

where is the s-th row of the W matrix and IK is the K × K identity matrix. This formulation adopts the premise that a priori the reduced rank model is valid on an average. With the rest of the prior specifications as before, the full conditional distribution of γ turns out to be Normal with mean vector and variance . Further the full conditional of σ2 still remains inverse-Gamma with the shape and scale parameters updated as the new shape = c1 + (p + K)/2 and new scale given by

The full conditional distribution of remains unchanged with β̂s,red replaced by .

3.3 Bayesian Ridge Regression

Lasso has been criticized in the literature to have weakness as a variable selector in presence of multi-collinearity. Although variable selection is not the main focus of this investigation, we will compare the standard lasso with a ridge-type penalty that will replace (12) with the criterion function . This turns out to be a special case of the lasso formulation where the ’s are assumed degenerate variables taking a constant value, say . In the prior specification for Bayesian lasso, we can simply drop the prior for τs and proceed. In the following sections we use the notation β̂two, β̂lasso, and β̂ridge to refer to the estimators from the two-stage lasso, Bayesian lasso, and Bayesian ridge methods, respectively.

4. Janus NHL Study

We implemented various estimation methods described in this article on a dataset of organochlorines and non-Hodgkins lymphoma from the Janus Cohort of Norwary (Engel et al. 2007), the motivating example for our investigation. The cohort, established in 1972, includes 317,000 men and women who provided blood samples during routine county health examinations in Norway (90%) and as Red Cross blood donors in Oslo (10%) (Langseth et al. 2009). A total of 194 cases with sufficient blood serum for PCB measurements collected between 1972 and 1978, and who had no previous cancer diagnoses at the time of recruitment, were identified by the Cancer Registry of Norway as having a diagnosis of NHL at least 2 years after recruitment and before the year 1999. One unaffected control was matched to each NHL case by sex, date of health examination (±3 months), county of residence and age (±1 year) at the time of health examination. Thirty six PCB congeners were measured using the blood serum from these individuals. In this paper we consider data on the concentrations of these congeners available from 190 complete case-control pairs.

For illustrating our proposed method, we dichotomized each congener based on the congener-specific medians among the controls. The system described by Wolff et al. (1997) combines the congeners into three clusters representing (i) estrogenic properties (6 congeners), (ii) antiestrogenic/immunotoxic/dioxinlike properties (5 congeners), and (iii) enzyme-inducing properties (9 congeners). Sixteen unassigned congeners were collectively referred to as “un-known” in our analyses. The 36 × 4 W matrix represents the total number of PCBs in a cluster the person is exposed to (Supplementary Table S1). All analyses were adjusted for two potential confounders, namely, body mass index (normal/overweight/obese) and smoking status (never/past/current).

4.1 Analyses

We obtained the MLEs β̂full and β̂red and the associated 95% confidence intervals by fitting conditional logistic regression models using equations (2), (3), and (4). The EB estimates EB1 and EB2 were obtained via equations (8)–(10). The corresponding 95% confidence intervals were obtained using a bias-corrected bootstrap approach with 1000 resampled data sets, each consisting of 190 case-control pairs sampled at random from the NHL data.

The hierarchical Bayes estimates β̂two, β̂lasso and β̂ridge were obtained using a MCMC approach by running a chain of length 50,000, sub-sampled every 50th iteration after an initial burn-in of 4,000 samples. For our prior specification we took c1 = c2 = 2, yielding a Gamma distribution for σ−2 a priori with mean = 1, and variance = 1/2. Further, we took a = 5, b = 1, in the gamma prior formulation in step (iii) in Section 3.1. For the ridge regression, we took . We can make statements about statistical significance of the congeners under the MLE and EB methods based on whether or not 0 is included in the confidence intervals. Such statements are not meaningful under hierarchical Bayes methods. Instead, to quantify the strength of association between the individual congeners and disease risk, we calculate the posterior association summaries P(β̂s > 0|data) for s = 1, ⋯, 36 congeners, and examine if these summaries are greater than some desired cut-off (say, 95% or 80%). However, since the estimated effects may be positive or negative in practical settings, we calculated max {P(β̂s > 0|data), P(β̂s < 0|data)} as our posterior association summaries.

4.2 Results

Only three congeners, PCB128, PCB167 (both antiestrogenic congeners) and PCB151 (un-known biological activity) were deemed statistically significant based on the full model analysis (see Table 1). The reduced model MLEs β̂red were considerably attenuated. Lengths of the 95% confidence intervals were substantially smaller than the full model MLEs β̂full. Despite that, the intervals for all congeners included 0. This clearly points towards the bias induced by the reduced method. Note that there were only four distinct β̂red values, each representing a grouping cluster. Given the overwhelming lack of signal within a given cluster, the non-significance of β̂red is not surprising. To obtain further insights into the reduced model MLEs, we examined the magnitudes of the components of r̂ = β̂full − β̂ red. For the NHL data, r̂ ranged from −1.578 to 0.787 (mean = 0.004, median = 0.015, standard deviation = 0.545), suggesting some modest discrepancies in the estimates for at least some of the congeners.

Table 1.

Parameter estimates and 95% confidence intervals (in parentheses) for MLE, EB1 and EB2 analyses. The empirical Bayes analyses use W from Supplementary Table 1. Results shown are only for the congeners found significant in the full ML analysis.

| Group | Congener | MLE | EB | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β̂full | β̂red | EB1 | EB2 | ||

| Anti Estrogenic | PCB128 | 0.611 (0.02, 1.203) |

0.146 (−0.008, 0.3) |

0.597 (−1.116, 1.262) |

0.427 (−0.487, 0.886) |

| PCB167 | 0.933 (0.175, 1.691) |

0.146 (−0.008, 0.3) |

0.909 (−0.941, 1.755) |

0.428 (−0.279, 0.885) |

|

| Unknown | PCB151 | −0.835 (−1.461, 0.209) |

−0.075 (−0.202, 0.051) |

−0.812 (−1.655, 0.5) |

−0.489 (−0.965, 0.274) |

The EB1 estimates were similar to β̂full. To understand this, we examined the vector Σ(Σ + A)−1 r̂, which plays a crucial role on the magnitude of the EB estimates (8). For EB1, we have A = r̂r̂T. It follows (see, e.g. Rao 1973) that

| (13) |

Thus, EB1 uniformly shrinks the components of r̂ towards 0. The amount of shrinkage is identical for all the components and depends upon the magnitude of the scalar r̂TΣ−1r̂. For the NHL data, this scalar was 31.84, which amounts to multiplying each component of r̂ by 1/32.84 = 0.03 i.e., 97% shrinkage. Thus the components of the vector Σ(Σ + A)−1 r̂ were close to 0 for the NHL data, drawing the EB1 estimates close to β̂full. In contrast, the EB2 estimates were attenuated relative to β̂full. For EB2, we have Σ (Σ + A)−1 r̂ = (AΣ−1 + I)−1r̂, where . Thus the amount of shrinkage of the components of r̂ is non-constant which in turn results in a non-uniform attenuation of β̂full. The 95% confidence intervals of both EB1 and EB2 estimates were considerably wider than those of β̂full and included 0, demonstrating variance inflation for these estimates due to the dependence of Σ and r̂ on β̂full and β̂red (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 2 shows partial results of the hierarchical Bayesian analyses. For each PCB congener, this table shows the estimated values of the posterior mean, posterior median (in italics) and 95% Bayesian credible interval (in parentheses). The lengths of the credible intervals of the hierarchical Bayesian methods were smaller than the lengths of the confidence intervals of β̂full. However, they were wider than the confidence intervals of β̂red, which may be due to the fact that, unlike the Bayesian methods, the reduced model does not account for variance inflation associated with the hierarchical nature through which the effects are estimated. The posterior mean and median of each congener were fairly close, suggesting that the distributions were not skewed. In general, the posterior means were attenuated relative to β̂ full. The posterior association summaries were greater than 95% for PCB128, PCB167, and PCB151 under all the three hierarchical Bayes methods. In addition, PCB049, PCB187 (both estrogenic congeners), PCB099 (enzyme inducing congener) and PCB209 (unknown biological activity) had posterior association summaries > 80% under all three methods. Results for all congeners are relegated to Supplementary Table S3.

Table 2.

Mean, median (in italics), and 95% Bayesian credible intervals (in parentheses) for Bayesian ridge, Bayesian lasso and Two-stage lasso methods. These analyses use W from Supplementary Table 1. The only congeners shown are those with posterior association summaries > 80%.

| Group | Congener | Bayesian Ridge | Bayesian Lasso | Two Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estrogenic | PCB049 | −0.348, −0.34 (−1.094, 0.373) |

−0.182, −0.17 (−0.646, 0.245) |

−0.162, −0.133 (−0.64, 0.215) |

| PCB187 | −0.457, −0.456 (−1.285, 0.293) |

−0.241, −0.216 (−0.799, 0.21) |

−0.166, −0.138 (−0.677, 0.239) |

|

| Anti Estrogenic | PCB128 | 0.522, 0.52 (0.044, 1.034) |

0.368, 0.355 (0.033, 0.771) |

0.357, 0.33 (0.056, 0.747) |

| PCB167 | 0.608, 0.604 (0.061, 1.208) |

0.348, 0.325 (−0.022, 0.841) |

0.343, 0.31 (−0.008, 0.866) |

|

| Enzyme Ind. | PCB099 | 0.4, 0.388 (−0.258, 1.101) |

0.233, 0.225 (−0.224, 0.746) |

0.175, 0.143 (−0.213, 0.658) |

| Unknown | PCB151 | −0.598, −0.589 (−1.114, −0.118) |

−0.353, −0.332 (−0.803, 0.022) |

−0.341, −0.311 (−0.841, −0.002) |

| PCB209 | −0.28, −0.278 (−0.857, 0.33) |

−0.178, −0.151 (−0.673, 0.198) |

−0.189, −0.153 (−0.645, 0.149) |

In summary, both the reduced model MLEs and hierarchical Bayes estimates were atten- uated but had substantial precision gains over the full model MLEs. The reduced model analysis failed to identify any significant congener while the hierarchical Bayes methods unequivocally suggested the same congeners found significant in the full model ML analysis as having strong association with NHL. Further, the Bayes methods identified four additional signals those were not picked up by the full model analysis. Since the reduced model MLEs and the hierarchical Bayes estimates are attenuated, a pivotal question is whether the precision gains of these estimates translate to better sensitivity for identifying the disease-related risk factors and better specificity for identifying the null risk factors relative to the full model MLEs. In the following section we investigate this issue using an extensive simulation study. Since EB tends to yield conservative inference, we do not conduct further investigations of its properties in our simulations.

5. Simulation

We conducted simulation studies to compare the ML estimators β̂full, β̂red, and the Bayes estimators β̂two, β̂lasso, and β̂ridge. Data on a total of F binary variables from N matched case-control pairs were generated such that the first T variables were associated with disease risk and the remaining F −T were null (i.e., not associated with the disease). In order to describe the simulation setup, denote the T disease-associated variables as (Xi,1, Xi,2, ⋯, Xi,T), where i ∈ {1, 2} indexes the individuals in a case-control pair. To produce a case-control pair, we first generated T independent Bernoulli variables with probability p = P(Xi,t = 1), t = 1, ⋯, T. The null variables, denoted Xi,j (j = T + 1, ⋯, F), were generated independently conditional upon the T disease-associated variables with probability P(Xi,j = 1|Xi,1, ⋯, Xi,T) = exp(Ai)/{1+exp(Ai)}, where . The F −T null variables were not causally related to disease risk, although they were generated to be correlated with the disease-related variables. We pre-specified an integer value 0 < T1 < T and obtained two disease risk factors as and . The conditional probability of being a case is:

| (14) |

where I(․) is the indicator function. We generated a uniform random variable U and assigned the case label to the first person in the pair if m < U, otherwise we assigned it to the second. This procedure was repeated independently to obtain N case-control pairs. In our setup, the T variables are associated with disease via a threshold model. In the binary context, this translates to the presence of more than one of the exposure variables in the respective groups. This model is motivated by observations in the health sciences where risk factors such as gene expressions must be under- or over-expressed below or above a certain level in order for them to increase disease risk.

The odds ratio parameters η1 and η2 allow us to tune the relative strength of association between the two risk factors and case-control status. Following McKelvey and Zavonia (1975), the proportion of explained variation in risk, denoted ρ2, is defined as

| (15) |

This measure has parallels to the concept of R2 in linear regression. In an application, one would calculate ρ2 by plugging the estimated values of η1 and η2 into (15), conditional upon the observed values of the risk factors. By contrast, η1 and η2 are fixed in our simulations and we use the theoretical variance p × (1 − p) of the Xij’s to evaluate the right hand side of (15). Rewriting η2 = ψ × η1, for given values of ρ2 and ψ, η1 is given by:

| (16) |

where θ1 = 1 − (1 − p)T1 − T1 × p × (1 − p)T1−1, and θ2 = 1 − (1 − p)T−T1 − (T − T1) × p × (1 − p)T−T1−1.

In our simulations, we set N = 100, F = 20, T = 10, T1 = 5, and p = 0.50. Further, we considered ψ ∈ {0.50, 1, 2} and ρ2 ∈ {0, 0.05, 0.10, 0.20}. Note that ρ2 = 0 represents the case when none of the variables are associated with disease risk. When ρ2 = 0, we have m = 0.5 in (14), indicating a completely random assignment independent of the risk factors. We generated one hundred data sets under each parametric configuration (ψ, ρ2). Here the strength of association can be compared across the risk factors through ψ only. When ψ = 0.50 (or 2), the first T1 = 5 variables have stronger (or weaker) signal than the next T − T1 = 5 variables.

We considered W to be a matrix of dimension F × 2, with the first column equaling 1 for the first T1 entries and 0 for the remaining F − T1 entries. The first T1 entries of the second column of W are zero, followed by 1 for the subsequent T −T1 entries and zero for all the remaining F − T + T1 entries. Each simulated data was fitted using the additive model described in (2) with all F variables as covariates. First we obtained β̂full and β̂red. The Bayesian estimates were obtained using MCMC methods and prior specifications as used for the analysis of the NHL data (see Section 4.1).

We compared the performances of the various analytic methods using their sensitivity and specificity. For the ML methods, sensitivity was defined as the empirical proportion of the true disease risk factors for which the 95% confidence interval excluded 0, averaged across the 100 simulated data sets. The specificity of these methods was similarly defined as the average empirical proportion of the null risk factors for which the 95% confidence interval included 0. The sensitivity and specificity of the full Bayes methods were obtained as follows. For each βs (s = 1, ⋯, F), we calculated the posterior association summary P(β̂s > 0|data) as the empirical proportion of positive values for that variable in the 1,000 MCMC samples. Sensitivity was the fraction of the true disease risk factors for which the posterior association summary exceeded some cutpoint, averaged across the 100 simulated data sets, and we considered cutpoints of 80% and 95%. Specificity was the fraction of the null risk factors for which the posterior association summary did not exceed the cutpoint of interest. When ψ ≠ 1, we calculated sensitivity separately for the true disease risk factors that had weak and strong signals.

Figure 1 shows the sensitivity and specificity as a function of the signal (ρ2) of the true disease risk factor. These results are shown for simulations with ψ = 2. The two columns of Figure 1 correspond to 80% and 95% probability cutoffs, respectively, for calculating sensitivity and specificity for the hierarchical Bayesian methods. Sensitivity increased as ρ2 increased for both strong and weak signals. Throughout, β̂full had the lowest sensitivity. All the three hierarchical Bayesian methods considered had higher sensitivity than the ML methods under an 80% cut-off. Both β̂lasso and β̂ridge had slightly smaller sensitivity than β̂red under a 95% cut-off. Among the hierarchical Bayesian methods, β̂two performed the best, while β̂lasso and β̂ridge yielded comparable results. Under 80% cutoff, the sensitivities of β̂lasso and β̂ridge were slightly smaller than that of the two-stage approach for detecting risk factors with strong signals. Good specificity (> 80%) was maintained by all the hierarchical Bayesian methods. Further, β̂lasso had higher specificity than β̂ridge under all the scenarios considered. This may be attributed to the fact that under Bayesian lasso, the prior for β is a mixture of normal and exponential distributions, which has a higher variation than the corresponding normal distribution (the prior distribution under the Bayesian ridge approach). The specificities of β̂two and β̂lasso were similar.

Figure 1.

Simulation results for sensitivity and specificity of the maximum likelihood and hierarchical Bayesian methods. Sensitivity is shown separately for risk factors having strong and weak signals. There are 10 true predictors (5 each with strong and weak signals) and 10 null predictors. These results are based on simulations with ψ = 2. In each figure, the horizontal axis is the variation in risk explained by the risk factors (ρ2), which determines the signal of the true disease risk factors.

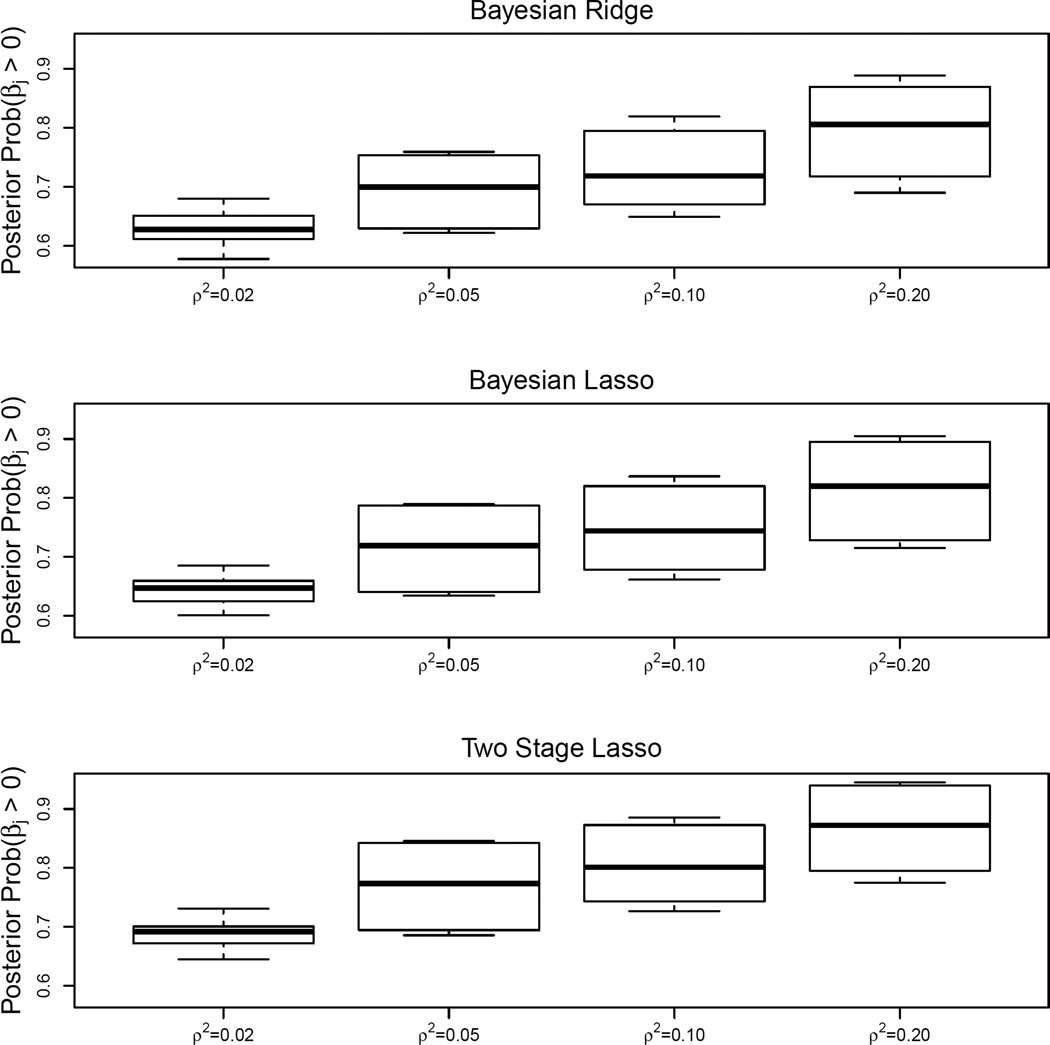

Figure 2 shows boxplots of the empirical estimates of the average posterior association summaries P(βs > 0|data) for the 10 true disease-related factors across different hierarchical Bayesian approaches. The posterior summaries increased as ρ2 increased for all three methods. For a given ρ2, β̂two had slightly higher average posterior summary than β̂lasso or β̂ridge. Figure 3 shows the boxplots of these average posterior summaries for the 10 null risk factors across the different Bayesian approaches. These summaries were close to 50%, as expected, under a broad range of values of ρ2 for β̂lasso and β̂ridge. For β̂two, the average posterior summary tended to deviate away from the 50% mark considerably with increasing ρ2.

Figure 2.

Box plots of the posterior probabilities P(βs > 0|data) for the 10 risk factors (5 having strong and 5 having weak signals) associated with the outcome based on data simulated with ψ = 2. The posterior probabilities are shown for analyses based on Bayesian ridge (top plot), Bayesian lasso (middle plot), and two stage lasso (bottom plot) methods. The horizontal axis in each plot is the true explained variation (ρ2).

Figure 3.

Box plots of the posterior probabilities P(βs > 0|data) for the 10 null risk factors based on data simulated with ψ = 2. The posterior probabilities are shown for analyses based on Bayesian ridge (top plot), Bayesian lasso (middle plot), and two stage lasso (bottom plot) methods. The horizontal axis in each plot is the true explained variation (ρ2).

5.1 Correlated Predictors

The findings reported above are made in the context of non-null predictors that act independently of each other. In reality, several of these predictors can be potentially correlated. In order to reflect this, we extend our simulation by generating non-null correlated predictors using a simple shared-frailty type algorithm. Specifically we generate T dichotomous variables X1, X2, …, XT following the two-stage strategy: Xi|U ~ i.i.d. Bernoulli(Up) and U ~ Beta(q, q), where Beta(q, q) is parameterized to have mean 1/2 and variance 1/(8q+4). We took q = 0.1 and p = 0.5 in our simulation, which yielded Corr(Xi, Xj) = 0.27, i ≠ j, i, j = 1, 2, …, T. We maintained T = 10 and F = 20 for ease of comparison with the independent case.

Supplementary Figures S1, S2 and S3 are drawn as direct comparators to Figure 1–3 in the main article. The patterns are generally similar across the scenarios. A comparison of Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S1 reveals that β̂full continue to be the one with worst sensitivity, while β̂red suffers from poor specificity, especially for larger ρ2. The performances of the Bayesian estimators are comparable, with the two-stage lasso performing best among them. This pattern is fairly consistent with that observed for the independent predictors case. The sensitivities are appreciably lower, however, compared to the independent case. The relative performance with regards to posterior association summaries are quite similar to that observed above. Estimates for the correlated case tend to be higher than those for the independent case when dealing with the non-null predictors.

5.2 Role of W

It is important to note that the performance of the estimators are sensitive to the choice of the clustering matrix W. This may have a critical implication when the true underlying cluster generating data does not match the prescribed structure of W. In order to compare the performance of the various methods under such a potential mismatch, we took W to be a F × 1 vector of all ones in our analytic model and carried out the entire analysis with data generated according to Section 5.1. Supplementary Figures S4, S5 and S6 provide the findings contrasting Figure 1 – 3, respectively. Supplementary Figure S4 shows that the sensitivities suffer substantially, presumably caused by the dilution effect of pooling all null and non-null covariates in a single cluster. A notable exception is observed for the case of β̂red for which the sensitivities increase quickly as a function of increasing ρ2. While this may point towards a superior performance of β̂red, in reality it is a function of the extreme clustering (β̂red is a constant multiple of the vector of ones). This becomes evident when one examines the specificities of β̂red, which are essentially complementary to the sensitivities, yielding the worst values. Specificity for the remaining estimates remain high irrespective of the amount of explained variation. The posterior association summaries in Supplementary Figure S5 show patterns that are similar to those in Figure 2, demonstrating increasing signal as a function of increasing ρ2. For the corresponding summaries for the null covariates, Bayesian ridge turns out to be most robust as the estimates derived from either of the remaining methods tend to drift away from the 50% line (Supplementary Figure S6).

5.3 Summary Findings

Several observations emerge from the simulation results. When the clustering matrix W match the underlying data generating scheme, the Bayesian approaches, especially the two-stage lasso perform fairly well (nearly always comparable to or better than the full maximum likelihood) with regards to sensitivity and specificity. Although the two-stage lasso has high sensitivity and specificity, it performs poorly in terms of the posterior association summary measure for the null predictors. In contrast, both the Bayesian ridge and Bayesian lasso have posterior association summaries that do not deviate considerably from the 50% mark for the null predictors. When there is a mismatch between the data generating W and the analytical one, the sensitivity-specificity criterion can be potentially misleading as demonstrated by our example. When a moderate to large proportion of variation in the data is explained by the exposures, the posterior association summary turns out to be a more reliable indicator of the signal. In this context, the Bayesian ridge is the most robust approach. The robustness prevailed even for the case of strongly correlated predictors.

6. Concluding Remarks

In this article, we have investigated Bayesian approaches to construct estimators of exposure association that can potentially have better performance than the traditional frequentist estimators such as MLE or EB. The methodology adopted are slight variants of approaches that have previously appeared in the literature. The novelty in the investigation lies in the context of application. The explosion of research in functional genomics is increasingly providing us with valuable information with biological pathways through which genetic and environmental exposures may contribute to disease etiology. These higher level pathway data facilitate a prognostic clustering of putative risk factors in a principled manner. It is anticipated that incorporating these data into analyses can facilitate a better understanding of disease risk factors (Thomas 2005). Reduced rank regression is a widely accepted practice in clinical epidemiology for incorporating pathway information in data analyses. A systematic study of full and reduced model MLEs, empirical and hierarchical Bayes in this context can shed light on practical benefits and limitations of these approaches. The main contribution of this article is in making initial strides towards such an investigation.

Both the full and reduced model MLEs suffer from issues relating to bias and precision. The shrinkage type estimation adopted in this article is geared towards improvement on these accounts. While EB estimation is based on the same philosophy, EB does not directly account for high levels of collinearity. Further, the standard error estimation in EB is, in general, a challenging issue. The Bayesian estimators in this article tackle the issue of associated predictors from a penalization angle. Further, the Bayesian approach, being based on model averaging, avoids having to confront standard error estimation of complex functions of the MLEs. The success of Bayesian modeling, of course, relies on an accurate prior model specification.

We have confined our discussion to 1:1 matching throughout the article primarily for the simplicity of exposition. The added complexity in dealing with m : n matching is purely computational, and not methodological. Further, the close tie between the likelihood expressions of the nested case-control study and proportional hazards regression in the context of time-to-event analysis speaks to a broader applicability of the developed methodology.

In the NHL data analysis, we have considered each congener to be a binary risk factor. Alternative ways of measuring the congeners, e.g. as continuous values or as categorical based on quantiles are available in literature (Engel et al. 2007). While the choice of an appropriate measurement for the congeners may itself constitute a vast and interesting investigation, the focus of our work here is on understanding the statistical properties of the shrinkage estimators under a given choice of measurement. Our investigations suggest that the Bayesian ridge is a robust estimator of the effects of the individual risk factors when it is of interest to incorporate thematic information about the risk factors into the analysis, but the accuracy of the user-specified themes is not known.

In the simulation studies of Section 5, we discuss the case where the null and the non-null covariates equal in number (10 null and 10 non-null variables). We have also run a number of additional scenarios where the number of null covariates dominate (say 4 or 5 times the number of non-null covariates). We found similar results - overall the Bayesian estimators continue to perform better than the full and reduced model MLEs and the empirical Bayes methods, with the Bayesian ridge emerging as a robust approach under a broad range of parametric configurations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The first two authors contributed equally to this work. The first author’s work was supported in part by research grant R01CA137420, Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA008748 from the National Cancer Institute, and grant UL1RR024996 from the Clinical and Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. The second author’s work was supported in part by the GI SPORE grant P50CA130810 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the offcial views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials

Web Appendices, Supplementary Tables, and Supplementary Figures referenced in Sections 2, 4, and 5 are available with this paper at the Biometrics website on Wiley Online Library. This website also includes computer programs for the proposed EB method based on the R programming language (R Core Team 2014), and computer programs for the Bayesian methods based on the WinBUGS software version 1.4.3 (Lunn et al. 2000) with an interface to R using rjags(http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rjags).

Contributor Information

Jaya M. Satagopan, Email: satagopj@mskcc.org.

Ananda Sen, Email: anandas@umich.edu.

References

- Anderson TW. Estimating linear restrictions on regression coefficients for multivariate normal distributions. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1951;22:327–351. [Google Scholar]

- Bae K, Mallick BK. Gene selection using a two-level hierarchical Bayesian model. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3423–3430. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow NE, Day NE, Halvorsen KT, Prentice RL, Sabai C. Estimation of multiple relative risk functions in matched case-control studies. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1978;108:299–307. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Morris C. Limiting the risk of Bayes and empirical Bayes estimators–Part I: The Bayes case. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1971;66:807–815. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Morris C. Limiting the risk of Bayes and empirical Bayes estimators–Part II: The empirical Bayes case. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1972;67:130–139. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman and Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Engel LS, Laden F, Anderson A, Strickland P, Blair A, Needham L, Barr D, Wolff M, Helzlsouer K, Hunter D, Lan Q, Cantor K, Comstock G, Brock J, Bush D, Hoover R, Rothman N. Polychlorinated biphenyl levels in peripheral blood and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: A report from three cohorts. Cancer Research. 2007;67:5545–5552. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiocco M, Putter H, van Houwelingen JC. Reduced rank proportional hazards model for competing risks. Biostatistics. 2005;6:465–478. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxi022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilks WR. Markov chain Monte Carlo. John Wiley and Sons; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hans C. Bayesian lasso regression. Biometrika. 2009;96:835–845. [Google Scholar]

- Langseth H, Gislefoss R, Martinsen JI, Stornes A, Lauritzen M, Andersen A, Jellum E, Dillner J. The Janus Serum Bank - From sample collection to cancer research. Oslo: Cancer Registry of Norway; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lunn D, Thomas A, Best N, Spiegelhalter D. WinBUGS - a Bayesian modelling framework: concepts, structure and extensibility. Statistics and Computing. 2000;10:325–337. [Google Scholar]

- McKelvey R, Zavonia W. A statistical model for the analysis of ordinal level dependent variables. The Journal of Mathematical Sociology. 1975;4:103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee B, Chatterjee N. Exploiting gene-environment independence for analysis of case-control studies: An empirical Bayes type shrinkage estimator to trade-off between bias and efficiency. Biometrics. 2008;64:685–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park T, Casella G. The Bayesian Lasso. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2008;103:681–686. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rao CR. Linear Statistical Inference and its Applications. New York: Wiley; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Reinsel GC, Velu RP. Multivariate reduced-rank regression: theory and applications. New York: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins H. Proceedings of the 3rd Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability. Vol. 1. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1955. An empirical Bayes approach to statistics; pp. 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM, Greenland S. The role of model selection in causal inference from nonexperimental data. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1986;123:392–402. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satagopan JM, Zhou Q, Oliveria SA, Dusza SW, Weinstock MA, Berwick M, Halpern AC. Properties of preliminary test estimators and shrinkage estimators for evaluating multiple exposures: application to questionnaire data from the study of nevi in children. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series C (Applied Statistics) 2011;60:619–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9876.2011.00762.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DC. The need for a systematic approach to complex pathways in molecular epidemiology. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2005;14:557–559. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-3-EDB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani RJ. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1996;58:267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Witte JS, Greenland S, Haile RW, Bird CL. Hierarchical regression analysis applied to a study of multiple dietary exposures and breast cancer. Epidemiology. 1994;5:612–620. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199411000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff M, Camann D, Gammon M, Stellman S. Proposed PCB congener groupings for epidemiological studies. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1997;105:13–14. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9710513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee T, Hastie TJ. Reduced-rank vector generalized linear models. Statistical Modelling. 2003;3:15–41. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.