Abstract

Background

Early postnatal exposure to general anesthesia (GA) may be detrimental to brain development, resulting in long-term cognitive impairments. Older literature suggests that in utero exposure of rodents to GA causes cognitive impairments in the first- as well as in the second-generation offspring never exposed to GA. Thus, we hypothesize that transient exposure to GA during critical stages of synaptogenesis causes epigenetic changes in chromatin with deleterious effects on transcription of target genes crucial for proper synapse formation and cognitive development. We focus on the effects of GA on histone acetylase (HAT) activity of cAMP-responsive element binding protein (CREB) Binding Protein (CBP) and the histone-3 acetylation status in the promoters of the target genes Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and c-Fos known to regulate the development of neuronal morphology and function.

Methods

7 day-old rat pups were exposed to a sedative dose of midazolam followed by combined nitrous oxide and isoflurane anesthesia for 6 hours. Hippocampal neurons and organotypic hippocampal slices were cultured in vitro and exposed to GA for 24 hours.

Results

GA caused epigenetic modulations manifested as histone-3 hypoacetylation (decrease of 25-30%, n=7-9) and fragmentation of CBP (2-fold increase, n=6) with 25% decrease of its HAT activity, which resulted in down-regulated transcription of BDNF (0.2 to 0.4-fold, n=7-8) and c-Fos (about 0.2-fold, n=10-12). Reversal of histone hypoacetylation with sodium butyrate blocked GA-induced morphological and functional impairments of neuronal development and synaptic communication.

Conclusions

Long-term impairments of neuronal development and synaptic communication could be caused by GA-induced epigenetic phenomena.

Keywords: isoflurane, histone acetylation, learning and memory, synaptic transmission, CBP, CREB

Introduction

Exposure of very young children to general anesthesia (GA) is becoming a common occurrence. Although this practice traditionally was considered innocuous, rapidly emerging animal1-4 and human5-7 findings suggest that GA could be detrimental to synaptogenesis, resulting in long-term cognitive impairments. Older literature suggested similar long-lasting effects; in utero exposure of rodents to GA caused cognitive impairments not only in the first generation offspring, but also in the second generation offspring never exposed to GA but born to dams exposed to GA in utero.8 This result suggests that a transient exposure to GA during a critical period of neuronal remodeling causes changes that become embedded in the genetic information resulting in the impairment of proper and timely neuronal development.

Epigenetic mechanisms translate environmental influences into changes in the expression of target genes having significant roles in brain development. For example, administration of ethanol, the oldest anesthetic known to mankind, during critical stages of brain development causes significant chromatin remodeling9,10 in the promoters of several target genes – Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and c-Fos in particular - responsible for long-term cognitive impairments.10,11 Epigenetic changes are critical for long-term memory storage; inhibition of histone deacetylase (HDAC), which removes acetyl groups from lysines on histone tails, increases histone acetylation, which in turn increases the expression of c-Fos and BDNF genes, thus enhancing new memory formation.12,13

Of particular interest for this study is the finding that modulation of the cAMP response element-binding (CREB) protein, a transcription factor that regulates the expression of several genes required for acquisition and storage of new memories, causes cognitive impairments.14,15 In fact, the human disease Rubinstein-Tayby syndrome, which is clinically manifested as significant mental retardation16 was found to be caused by dysfunctional and down-regulated CREB-binding protein (CBP).17 CBP also plays an important role as a histone acetyl transferase (HAT), which acetylates specific lysine residues in histones, thereby generating epigenetic changes that disrupt repressive chromatin structure. Collectively, these findings suggest that drugs or diseases that promote epigenetic changes could induce long-term molecular signals leading to the impairment of neuronal development.

Here we show that exposure to GA during critical stages of synaptogenesis modulates the expression and function of the key transcription factors CBP and CREB. We suggest that the CBP and CREB modulation, in turn, causes epigenetic changes manifested as histone hypoacetylation leading to down-regulated transcription of the target genes c-Fos and BDNF that play an important role in neuronal development.11,18 We used our routine in vivo anesthesia protocol that causes impairment of synaptogenesis19 and cognitive deficits1 in which postnatal day (P) 7 rats are exposed to a sedative dose of midazolam (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (9 mg/kg, i.p.) followed by 6 h of combined nitrous oxide (70%) and isoflurane (0.75%).

Materials and Methods

Animals

We used 7 day-old (P7) Sprague-Dawley rat pups (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) for all experiments since this age is when rat pups are most vulnerable to anesthesia-induced neuronal damage2. Our routine anesthesia protocol was as follows: experimental rat pups were exposed to 6 h of anesthesia and controls were exposed to 6 h of mock anesthesia (vehicle + air). After the administration of anesthesia, rats were reunited with their mothers until sacrifice – within the first two hours or at 24 h post-anesthesia (at P8). They were divided randomly into three groups: one group for assessing expression of several proteins using the Western blotting technique, the second group for gene expression studies using real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays and the third group for functional studies of histone acetylase (HAT) and deacetylase (HDAC) activity using an enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA). Our randomization process was designed to provide each group with roughly equal representation of pups from each dam.

The experiments were approved by the Animal Use and Care Committee of the University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA and were done in accordance with the Public Health Service's Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used.

Anesthesia administration

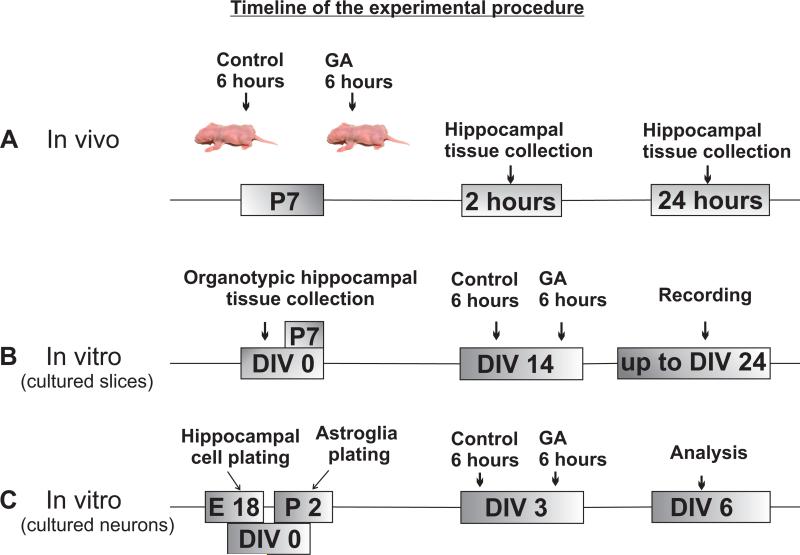

Considering that the length of GA exposure in the in vitro system could not be reliably (and directly) correlated with the length of exposure in the in vivo system, we chose two distinct time points reported in previous studies to result in robust anesthesia-induced developmental neurotoxicity - 6 h-exposure in animals1 and 24-h exposure in hippocampal cultures.20,21 We reasoned that if epigenetic changes are to be considered relevant to previously reported impairments in neuronal and glial development and survival, we should detect robust epigenetic changes caused by the same respective durations of exposure. The flow diagram of the timing of anesthesia administration as well as the tissue collection and processing is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline of the experimental procedures for in vivo and in vitro general anesthesia (GA) exposures and tissue collection.

To achieve general anesthesia we used our routine anesthesia combination whereby P7 rat pups received a single injection of midazolam (9 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) followed by 6h of nitrous oxide (70%), isoflurane (0.75%), and oxygen (approximately 30%). For control experiments, air was substituted for the gas mixture. The measured fraction of inspired oxygen in both control and experimental conditions was 0.29-0.30. Nitrous oxide and oxygen were delivered using a calibrated flowmeter. Isoflurane was administered using an agent-specific vaporizer that delivers a set percentage of anesthetic into the anesthesia chamber. Midazolam was dissolved in 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) just before administration. For control animals, 0.1% DMSO was used alone. To administer a specific concentration of nitrous oxide/oxygen and isoflurane in a highly controlled environment, an anesthesia chamber was used. Rats were kept normothermic and normoxic while glucose homeostasis was maintained within normal limits throughout the experiment.2,3 After initial equilibration of the nitrous oxide/oxygen/isoflurane or air atmosphere inside the chamber, the composition of the chamber gas was analyzed with an infrared analyzer (Datex Ohmeda, Madison, WI) to establish the concentrations of nitrous oxide, isoflurane, carbon dioxide, and oxygen.

Western blot studies

For protein quantification, we dissected the hippocampus proper (which included hippocampus and subiculum) immediately after the brains were removed from the individual pups using a dissecting scope (10x magnification). Tissue was collected on ice and was snap-frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. The protein concentration of the lysates was determined with the Total Protein kit using the Bradford method (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). 10-25 μg of total protein was heat-denatured, and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) through 4-20% Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gradient gels (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Separated proteins were transferred to polyvinidine difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA), blocked at room temperature for 1 h in 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) followed by incubation at 4 °C overnight with primary antibodies: rabbit polyclonal anti-CBP (1:750, A-22: sc-369, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX), rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-CREB (1:2500, Ser133: 06-519, Millipore, Billerica, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-CREB (1:1000,AB3006, Millipore, Billerica, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-c-Fos (1:1000, K-25: sc-253, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX), rabbit polyclonal anti-acetyl-Histone H3 (1:3000, 06-599, Millipore, Billerica, MA), mouse monoclonal anti-lamin A/C (1:500, clone 14:05- 714, Millipore, Billerica, MA), anti-Histone 3 (1:3500 Millipore, Billerica, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-BDNF (1:1000, N20-SC-546, Santa Cruz Biotechnology or anti-BDNF (1:1000, ANT-010) (Alomone labs, Israel), with anti-β-actin (1:10000 Sigma Aldrich) or anti-glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 1:16500 Millipore, Billerica, MA) antibodies as loading controls.

Membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies - goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse IgG (1:10000, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX). Immunoreactivity was detected using enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Super Signal west Femto; Thermo Scientific, UT). Images were captured using GBOX (Chemi XR 5, Syngene, MD) and gels were analyzed densitometrically with the computerized image analysis program ImageQuant 5.0 (GE Healthcare, Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Enzymatic activity of HATs and HDACs

HATs and HDACs activities were measured using commercially available HAT/HDAC Activity Assay ELISA kits (Epigentek, New York, USA) with a colorimetric detection method according to manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 10 μg of hippocampus proper nuclear extract was used and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, CA, USA). All experiments were performed in triplicate. The enzyme activities were calculated using a standard curve and were expressed as activity per hour per mg of protein (A·h−1mg−1). To measure HAT activity of CBP we first isolated CBP using an immunoprecipitation kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), then used a colorimetric ELISA assay kit (Epigentek), which measures the ratio between acetylated and unacetylated histones. This ratio is directly proportional to the CBP's HAT activity. Absorbance at 450 nm was determined using a spectrophotometer.

Hippocampal cell culture and cultured slice preparations

Hippocampal cells were co-cultured with astroglia using a “SANDWICH” method. Primary cultures of astrocytes were prepared from 1-2-day old Sprague-Dawley rat pups.22 Briefly, we freed brain tissue from meninges and dissected away the cerebellum, olfactory bulb, and brainstem under a laminar flow hood. Remaining tissue was chopped finely in a drop of calcium- and magnesium-free Hank's balanced salt solution (CMF-HBSS; Gibco BRL), then tissue pieces were transferred to a 50 ml conical centrifuge tube (Corning, Corning, NY) in a final volume of 15 ml CMF-HBSS with 2.5% trypsin (Gibco BRL) and 1% DNAse (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and incubated in a 37 ° C water bath for 5 minutes, swirling the tube occasionally. After centrifugation at 120 x g for 5 minutes to remove enzymes and lysed cells, the pellet was resuspended in Glia medium (Minimum Essential Medium with Earle's salts containing 10% horse serum (Gibco BRL), 6% glucose, and penicillin- streptomycin (Gibco BRL). The plated density was approximately 7.5 × 106 cells per 75-cm2 flask (Corning). Cultures were grown in an incubator in a constant humidified atmosphere of 5% carbon dioxide and 95% air at 37 ° C . Medium was changed the day after plating and every third day thereafter. When the cells were near confluence (usually within 7-10 d), astroglia were harvested and passaged into 60-mm dishes at approximately 105 cells/dish. The day of plating was designated as Day-1 in vitro 0 (DIV0). When cells reached 40%-70% confluence, they were ready to be co-cultured with neurons. Glia medium was removed one day before co-culturing and replaced with Neuronal Maintenance Medium containing Neurobasal Medium (Gibco BRL), GlutaMAX- I supplement and B27 serum-free supplement for preconditioning.

To prepare hippocampal primary cultures, we used E18 rat fetuses. Their brains were dissected and placed in a dish containing CMF-HBSS. The neurons were dissociated using 2.5% trypsin. Cell density was determined using a hemocytometer and 1.5×105 hippocampal cells were plated per 60 mm dish using poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in neuronal Maintenance Medium for a low density culture. After 3-4 h the dishes were examined to ensure that most of the cells had attached, and then coverslips were inverted so that the paraffin feet are resting on the bottom of the dish. The ratio of astrocyte:neurons was about 2:3 (1 × 105:1.5 × 105 per 60 mm culture dish) and did not vary substantially from one culture dish to another. We allowed the glia and neuronal co-culture to grow for 3 days. Neurons that are dead or dying do not remain attached to the bottom of the dish; they float and are readily removed with each change of a medium. This assures that dead or dying neurons are eliminated before a given treatment is initiated. The screening prior to any given experiment was done by an experienced experimenter to assure similar neuronal densities between the dishes without disturbing neuronal viability. The dishes were then randomized before being assigned to any given experimental condition to avoid selection bias.

For in vitro treatments of the co-cultures we followed the following protocol: One hour prior to anesthesia exposure the hippocampal glia “sandwich” co-cultures were treated with 5 mM Sodium butyrate (NaB; Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Japan). Hippocampal neurons and glia co-cultures were then exposed to anesthesia for 24 h at DIV3 in a chamber at 37 ° C with a humidified atmosphere using 25 μg/ml midazolam, 0.75% isoflurane, 70% nitrous oxide, and about 30% oxygen. Sham control dishes were kept in a chamber at 37 ° C in a humidified atmosphere containing air. The chamber design enabled the gas composition to which culture dishes were exposed to be analyzed continuously using an infrared analyzer (Datex Ultima, Chalfont, St. Giles, United Kingdom). After 24 h, the dishes were taken out of the anesthesia chamber, medium was changed immediately and dishes were placed in an incubator. We allowed the cells to grow for up to 3 days after anesthesia for confocal imaging (Zeiss, Germany). Since the dead or dying neurons do not remain attached and, thus, are removed with each medium change, only live neurons were stained, counted and analyzed for branching as described in the Histological Assessment.

Organotypic hippocampal cultured slices were prepared from postnatal 6–7 day-old male and female Sprague Dawley rats, per our previous studies.23,24 All procedures for animal surgery and maintenance were performed following protocols approved by the Animal Care & Use Committee of the University of Virginia and in accordance with US National Institutes of Health guidelines. The hippocampi were dissected out in ice-cold Hepes-buffered Hanks’ solution (pH 7.35) under sterile conditions, sectioned into 400 μm slices with a tissue chopper, and explanted onto a Millicell-CM membrane (0.4-μm pore size; Millipore, Billerica, MA). The membranes were then placed in 750 μl of MEM culture medium containing (in mM): Hepes, 30; glutamine, 1.4; D-glucose, 16.25; NaHCO3, 5; CaCl2, 1; MgSO4, 2; plus 20% heat-inactivated horse serum, 1 mg/ml insulin, and 0.012% ascorbic acid at pH 7.28, with a final osmolarity 320 mM.

Histological Assessment

Coverslip cultures were taken from 3 different dishes of neuronal co-culture sandwich preps obtained from a total of 15 pups. Neurons were fixed with cold (4 °C) paraformaldehyde at 4% in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). After fixation, permeabilization was done with 0.2% Triton X-100 containing 5% donkey serum for one hour at room temperature on a slow shaker. To stain neurons, we incubated cultures overnight at room temperature with Map2 primary antibody (Sigma Cat #M9942) diluted at 1:2000 in blocking solution followed by secondary antibody Alexa 488 (Invitrogen; 1:2000). To label glial cells, the cultures were rinsed and incubated with glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (Sigma; 1:800) followed by secondary antibody Alexa 594 (Invitrogen; 1:2000). The coverslips were mounted using the fluorescence mounting medium vectashield plus DAPI (Vector labs). The microglia contamination determined when using ‘sandwich’ co-cultures is approximately 4%.22

Immunostained coverslip cultures were examined with a confocal microscope (Zeiss, Germany). Coverslips were taken from 3 different dishes of neuronal co-culture sandwich preps obtained from a total of 15 pups. Five pictures were taken from areas of each coverslip using the same pattern (in the center and at 12, 3, 6 and 9 o'clock in a clockwise fashion). We counted the number of neurons in each scene and expressed it per μm2. Neurons were identified based on their morphology as revealed by the Map2 staining, and analysis of dendritic branching was made by counting the number of primary branches on each neuron using Image-Pro Plus software. The histological analyses were done in blinded fashion.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from hippocampal tissue with TRIZOL (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA (2 μg) was converted to first strand cDNA using the RT2 First Strand kit (Qiagen). The resulting cDNA was subjected to PCR analysis in a final volume of 25 L containing RT2SYBR Green qPCR Mastermix and BDNF (exon IV) primer.12 RT-PCR amplifications were performed in an iQ5 real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad) at 50 °C for 30 min, 95 °C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 60 s, 57 °C for 60 s, 72 °C for 60 s, and then 70 °C for 10 min. To amplify the c-Fos gene, conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 60 s with primers.25 qPCR Primers for ®-Tubulin (Forward: AGCAACATGAATGACCTGGTG, Reverse: GCTTTCCCTAACCTGCTTGG) or ®-actin (PPR06570C Qiagen) were included in every analysis as endogenous controls to check for total mRNA amount and differences in inter-assay amplification efficiency. Each sample was run in triplicate and the mean values of each CT were used for further calculations. Quantification was performed by the 2-ΔCT method26 and the changes in mRNA levels of BDNF exon IV (Forward: TGCGAGTATTACCTCCGCCAT, Reverse: TCACGTGCTCAAAAGTGTCAG); and c-Fos (Forward: GGAATTAACCTGGTGC TGGA, Reverse: TGAACATGGACGCTGAAGAG) were expressed relative to the control values.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (CHIP)

ChiP assays were performed using the ChIP Kit (catalog # 17-610, #17-245; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) according to the supplier's recommendations with slight modifications. Rat hippocampal tissue was removed using a dissecting microscope, minced with a razorblade to ~1 mm-sized pieces, and suspended in ice-cold PBS containing protease inhibitors. Tissue was cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde (Sigma) for 10 min at room temperature and the reaction was quenched with 0.125 M glycine for 5 min at room temperature. Cross-linked tissues were rinsed twice with cold PBS, collected and placed in cell lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors for 15 min at 4 °C, and homogenized twice for 10 sec on ice. Pelleted nuclei were re-suspended in nuclear lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors. Chromatin was then sonicated using a Branson Sonifier 250 using a small probe at 50% output for 15 sec (1 sec on / 1 sec off) for 10 cycles each in an ice bath. Fragmented chromatin was analyzed by electrophoresis through a 1.5% agarose gel to confirm efficient sonication (generation of ~ 500 200-bp-fragments). Collected chromatin was diluted 10-fold in ChIP dilution buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail and 1% of the material was reserved for “input” control. Immunoprecipitation was performed at 4 °C overnight by rotation with magnetic protein A beads and anti-H3ac (Upstate, 06-599) or normal rabbit IgG as a control (Upstate, PP-64b). The magnetic beads were pelleted and washed two times with a low-salt wash buffer, then a high-salt wash buffer, then lithium- chloride immune complex wash buffer, and then with Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer.

DNA was eluted using the ChIP elution buffer, then crosslinks were reversed with proteinase K treatment for 2 h at 65 °C in an Eppendorf Thermomixer for 10 min at 95 °C. For the final step, samples were eluted using spin columns in 30 μl of TE elution buffer.

Acetylated Histone 3 in c-Fos and BDNF-IV promoters was assessed by measuring the gene expression levels in immuno-precipitated DNA using real time (RT)- PCR. Triplicates of 1 μl purified DNA and 1% input DNA (diluted 10-fold) were analyzed with iTaq Universal SYBR green supermix using ChIP-qPCR analysis in the CFX96 Connect real-time PCR system (BIORAD). The following primer pairs were used: for c-Fos, forward: AAA ACT GGA GTT TAT TTT GGC, and reverse: CAC AGA CAT CTC CTC TGG; BDNF-IV, forward: CTC CGC CAT GCA ATT TCC AC, and reverse: GCC TTC ATG CAA CCG AAG TA. Promoter occupancy was plotted as fold enrichment (2−ΔCT) over input after subtracting the background signal from the IgG control. ChIP-PCR also was controlled using the GAPDH promoter.

Electrophysiological studies

Modulation of hippocampal synaptic transmission was assessed with electrophysiological patch-clamp recordings by focusing on synaptic GABAA-mediated currents. We used hippocampal slices from P7 rat pups and cultured for up to 2 weeks following the procedure described by McCormack et al.27 Slices were exposed to our routine GA protocol (25 ug/ml midazolam, 70% nitrous oxide and 0.75% isoflurane for 24 h). GABA-dependent miniature inhibitory post-synaptic currents (mIPSCs) were recorded in pyramidal neurons of the CA1 hippocampal region up to 10 days post-treatment in the presence of 1 μM tetrodotoxin (TTX) (to block action potentials) and 5 μM NBQX (2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo[f]quinoxaline-2,3-dione) and 50μM d-APV (d-2R)-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid); [to block AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid) and NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) currents, respectively)].

Statistical analysis

Comparisons among groups were made using unpaired two-tailed t test, with the exception of electrophysiological studies that were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. Using the standard version of GraphPad Prism 5.01 software (Media Cybernetics, Inc, Bethesda, MD), we considered p<0.05 to be statistically significant. All data are presented as means + SD. No experimental data were missing or lost to statistical analysis. The sample sizes reported throughout the Results and in the Figure Legends represent biological replicates and were based on previous experience.1,4,19 In response to concerns raised by reviewers, the sample size was increased for several experiments, but no attempts were made to adjust for interim analyses.

Results

To begin to decipher GA-induced epigenetic changes during synaptogenesis, we first examined whether early exposure to our routine anesthesia protocol modulates the protein expression and function of two transcription factors, CREB and CBP, both known to be exquisitely sensitive to changes in neuronal activity and best understood as transcription factors linking epigenetic with classic gene regulatory mechanisms.14,15,17

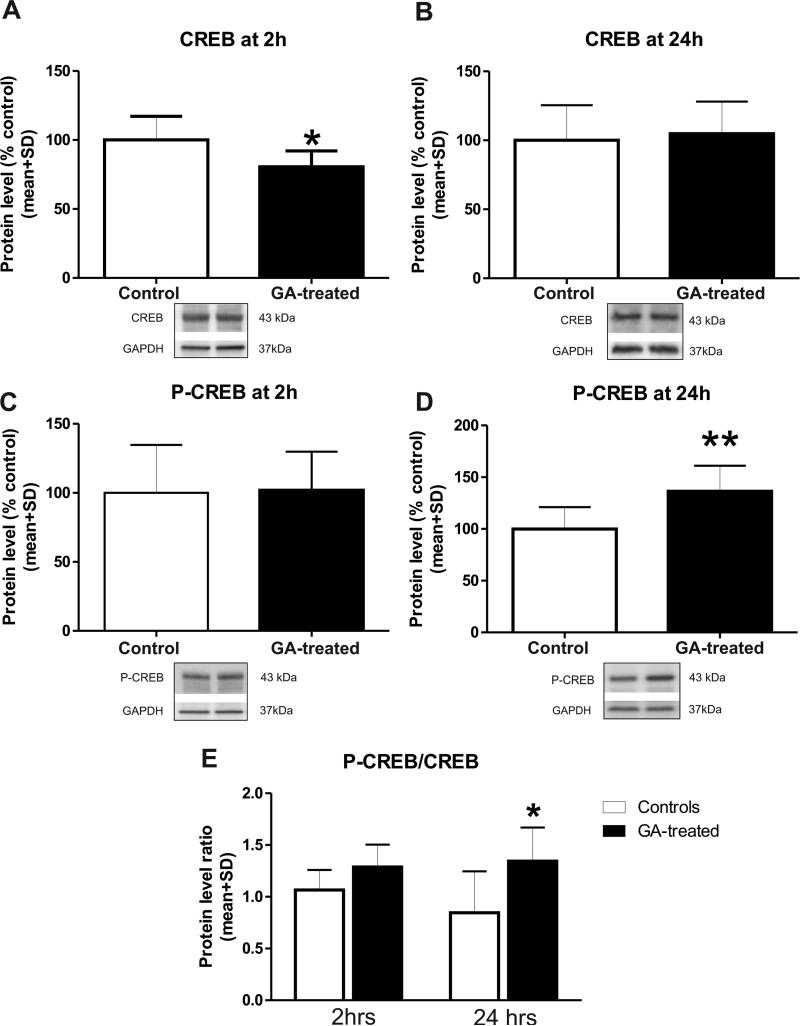

We found that there is a significant decrease in total CREB protein expression (Figure 2) at 2 h (Fig. 2A, p=0.048, n=6 per data point) and no change at 24 h post-GA (Fig. 2B, p=0.72, n=7). The levels of activated (phosphorylated) CREB protein in hippocampal complex were not changed at the 2 h time point (Fig. 2C, n=10; p=0.884) but were increased significantly at the 24 h time point (Fig. 2D; **, p=0.002; n=10). Consequently, the ratio between phosphorylated and total CREB was increased in GA-treated animals compared with their respective controls at 2- and 24 h time points (Fig. 2E; *, p=0.0246 at 24h), suggesting that GA promotes CREB activation.

Figure 2. Anesthesia increases phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding (CREB) in the immature hippocampus after 24 h.

The expression of CREB total and phosphorylated protein fractions was estimated by Western blotting in fresh hippocampal tissue obtained from P7 rat pups soon at 2 h or 24 h (at P8) post-anesthesia or sham treatment. The protein levels were expressed as percent change from sham controls after normalization to glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). (A) Anesthesia caused a significant decrease in total CREB protein expression at 2 h (*, p=0.044; n=6). (B) Anesthesia caused no change in total CREB expression at 24 h (p=0.72; n=7). (C) Anesthesia caused no change in the level of activated (phosphorylated) CREB protein in developing hippocampus at 2 h (p=0.884; n=10). (D) Anesthesia significantly increased the level of activated (phosphorylated) CREB protein in developing hippocampus at 24 h (**, p=0.002; n=10). (E) Calculated ratio between phosphorylated and total CREB was significantly increased in anesthesia-treated animals compared with their respective controls at 24 h (*, p=0.025).

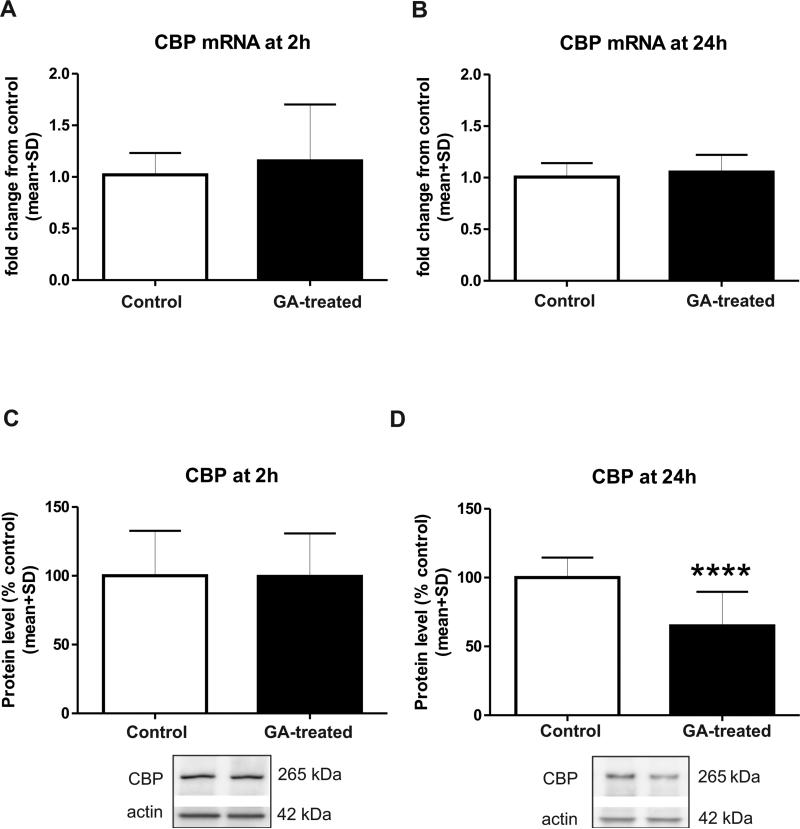

The expression of CBP mRNA in the hippocampal complex was not changed (Figure 3) at either 2 h (Fig. 3A) or 24 h (Fig. 3B) post-GA compared with controls; however, we found that the expression of full length CBP protein (270 kD) was not changed at 2 h post-GA (Fig. 3C) but was significantly reduced at 24 h (about 35%) (Fig. 3D), as compared with controls (Fig. 3A, n=6, p=0.58; Fig. 3B, n=6, p=0.59; Fig. 3C, n=12, p=0.97; and Fig. 3D, n=17; ***, p=0.0001).

Figure 3. Anesthesia decreases expression of full-length cAMP-responsive element binding protein (CBP) in the immature hippocampus.

Real time PCR shows that anesthesia does not affect expression of CBP mRNA in developing hippocampus at 2 h (A; p=0.584; n=6) or 24 h (B; p=0.591; n=6), as compared with age-matched controls. Western blot analysis shows that anesthesia does not affect the expression of full length CBP protein (270 kD) at 2 h (C; p=0.972; n=12) but that it causes significant (****, p=0.0001) reduction at 24 h (D; n=17), as compared with age-matched controls.

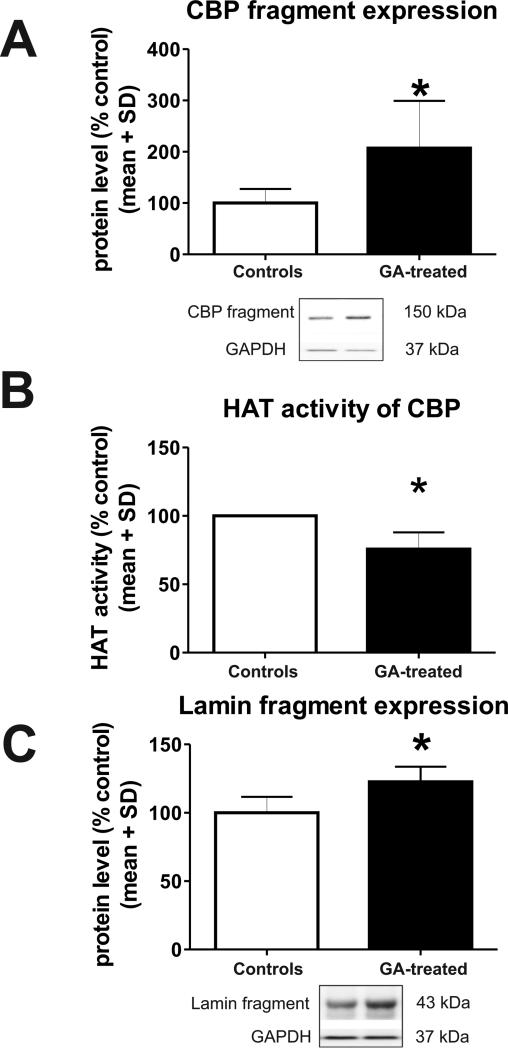

These findings suggest that GA exposure may cause post-translational down-regulation in full length (270 kDa) CBP protein expression, possibly due to CBP fragmentation. The increased production of 148 kDa fragments was of particular interest since it commonly occurs as a result of apoptotic neuronal damage. To address the possibility that GA, which is known to induce apoptotic neurodegeneration, could be causing CBP fragmentation, we quantified the expression of 148 kDa fragments (Figure 4) 24h post- GA and found a significant (*, p=0.021) increase (over 200%) in GA–treated animals compared with controls (Fig. 4A, n=6). Since undue fragmentation can lead to impaired HAT function of CBP, we assessed its activity at 24 h post-GA and found it to be significantly decreased (by about 25%; *, p=0.026) in animals treated with GA (Fig. 4B, n=3). Since there was a significant increase (over 20%; n=4; *, p=0.029) in the expression of fragmented lamin (41-50 kDa; Fig. 4C), a chromatin organization component and well- known substrate of activated caspase-6, it seems likely that CBP fragmentation is caused, at least in part, by GA-induced caspase-6 activation.

Figure 4. Anesthesia causes significant post-translational changes in cAMP-responsive element binding protein (CBP) in the immature hippocampus.

(A) Anesthesia induces significant increase in the 148 kDa CBP in the developing hippocampus at 24 h as compared with age- matched controls (n=6; *, p=0.021) suggestive of enhanced fragmentation. (B) Anesthesia causes significant decrease in CBP histone acetylase (HAT) activity at 24 h (*, p=0.026) in developing hippocampus as compared with age-matched controls (n=3). (C) Anesthesia causes significant increase in the expression of fragmented lamin (41-50 kDa), a chromatin organization component and well-known substrate of activated caspase-6 (n=4, *, p=0.029).

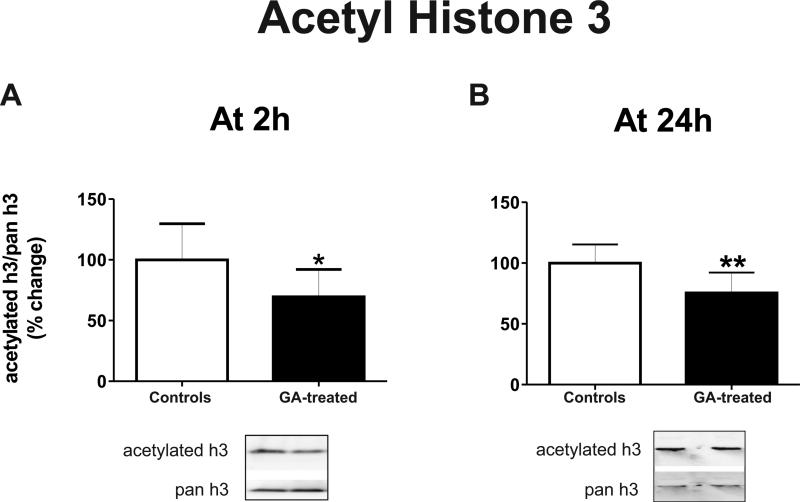

Since CBP is an important HAT enzyme regulating the degree of histone acetylation, and because its protein expression and HAT activity were down-regulated significantly by GA, we hypothesized that this effect may result in histone hypoacetylation. We probed the effect of GA on histone-3 (H3) acetylation, with a special focus on lysine residue 14 (H3K14), the most common target of CBP acetylation28 and one implicated in learning.29,30 The level of acetylated H3 was reduced significantly (about 25-30%, Figure 5) in the hippocampal complex at 2 h (Fig. 5A left panel; n=7 controls, n=8 GA-treated; *, p=0.042) and at 24 h (Fig. 5B right panel; n=9 per group; **, p=0.005) after exposure of rats to GA as compared with controls. Since the activity of the HDAC families of enzymes, known to regulate histone de-acetylation, was not changed after GA exposure (data not shown; n=5), the observed decrease in histone acetylation may be due mostly to a decrease in CBP protein and its HAT activity.

Figure 5. Anesthesia causes significant hypoacetylation of histone-3 (H3) in the immature hippocampus.

Anesthesia causes significant hypoacetylation at lysine residue 14 of histone-3 (H3K14) at 2 h (left panel; n=7-8; *, p=0.042) and at 24 h as compared with age-matched controls (n=9; **, p=0.005).

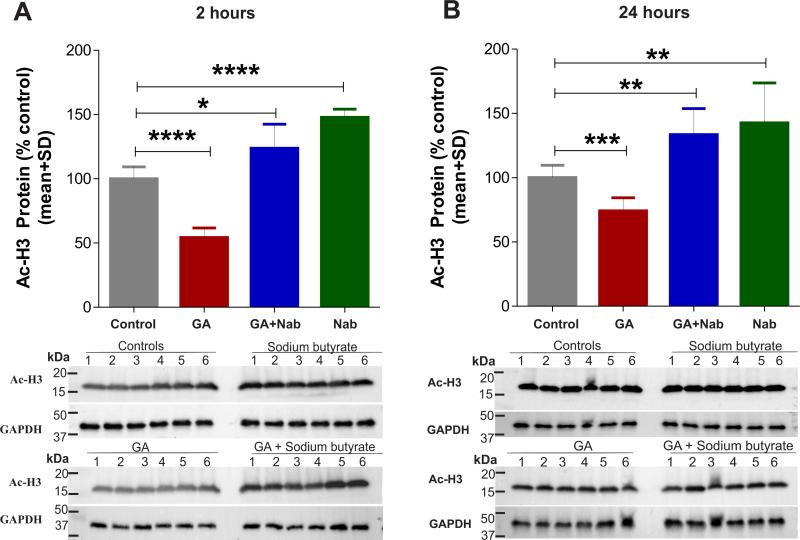

To determine whether the GA impairment of H3 acetylation might be mediated, in part, via effects on HDAC, we administered the global HDAC inhibitor NaB at 1.2 g/kg, ip31 60 minutes before tissue collection and measured the level of acetylated H3 2 h and 24 h post-GA (Figure 6). The GA-induced decrease in acetylation of H3 at 2 h (about 50%; ****, p=0.0001; n=6) (Fig. 6A) was not only completely reversed with NaB, but there was a significant increase in acetylation of H3 as compared with that in sham controls (about 24%; *, p=0.019; n=6). As expected, NaB alone caused increased acetylation of H3 as compared with that in sham controls (about 30%; ****, p=0.0001; n=6). At 24 h, the GA-induced decrease in acetylated H3 (about 25%; ***, p=0.001, Fig. 6B) was not only reversed with NaB but there was significant increase in acetylation of H3 compared with that in sham controls (about 33%; **, p=0.004; n=6). Again, NaB in the absence of GA increased acetylation of H3 as compared with that in sham controls (about 43%; **, p=0.009; n=6).

Figure 6. The global HDAC inhibitor sodium butyrate reverses general anesthesia (GA)-induced histone-3 hypoacetylation in the immature hippocampus.

Sodium butyrate (NaB) (at 1.2 g/kg, i.p.) was given 60 minutes before the tissue collection. (A) The GA-induced H3 hypoacetylation (****, p=0.0001; n=6) is not only completely reversed, but there is a significant increase in acetylated H3 as compared with sham controls (*, p=0.019; n=6). NaB alone, at this dose, also caused upregulation of acetylated H3 as compared with sham controls (****, p=0.0001; n=6 rat pups per data point). (B) NaB also reversed the GA-induced decrease in acetylated H3 at 24 h (***, p=001; n=6), and also resulted in significant increase in acetylated H3 compared with sham controls (**, p=0.004; n=6). Again, NaB alone caused an increase in acetylated H3 as compared with sham controls (**, p=0.009; n=6).

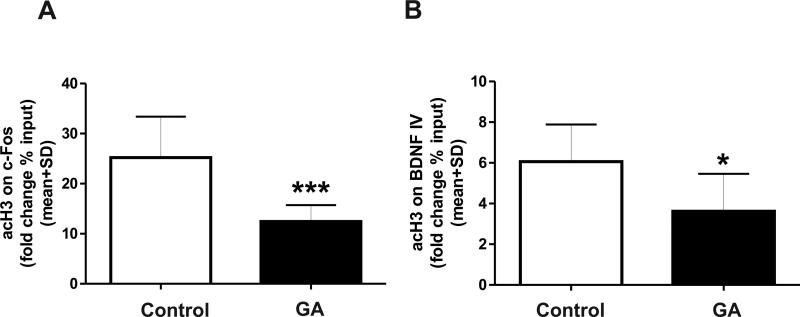

Although GA caused global H3 hypoacetylation, the hypoacetylated status of H3 in CREB binding sites of the promoter regions of c-Fos and BDNF target genes remained to be examined. Hence, we performed individual loci-specific ChIP assays and quantified the amount of DNA associated with hypoacetylated H3 on c-Fos and on exon IV of the BDNF gene (Figure 7). GA significantly decreased the expression of acetylated H3 at c-Fos (Fig. 7A, n=8; ***, p=0.001), at the BDNF promoter (Fig. 7B, n=6; *, p=0.043, and at the CREB transcription start sites, thus confirming that H3 hypoacetylation is not only global but also specific for our target genes c-Fos and BDNF.

Figure 7. Anesthesia causes histone-3 hypoacetylation in cAMP response element-binding (CREB) binding sites in the promoter regions of target genes c-Fos and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the immature hippocampus.

We used individual loci-specific ChIP assays and quantified the amount of DNA associated with hypoacetylated H3 on c-Fos and exon IV for BDNF genes. (A) Anesthesia significantly decreased the expression of acetylated histone-3 in the c-Fos promoter at the CREB transcription start sites (n=8; ***, p=0.001). (B) Anesthesia significantly decreased the expression of acetylated histone-3 in the BDNF promoter at the CREB transcription start sites (n=6; *, p=0.04).

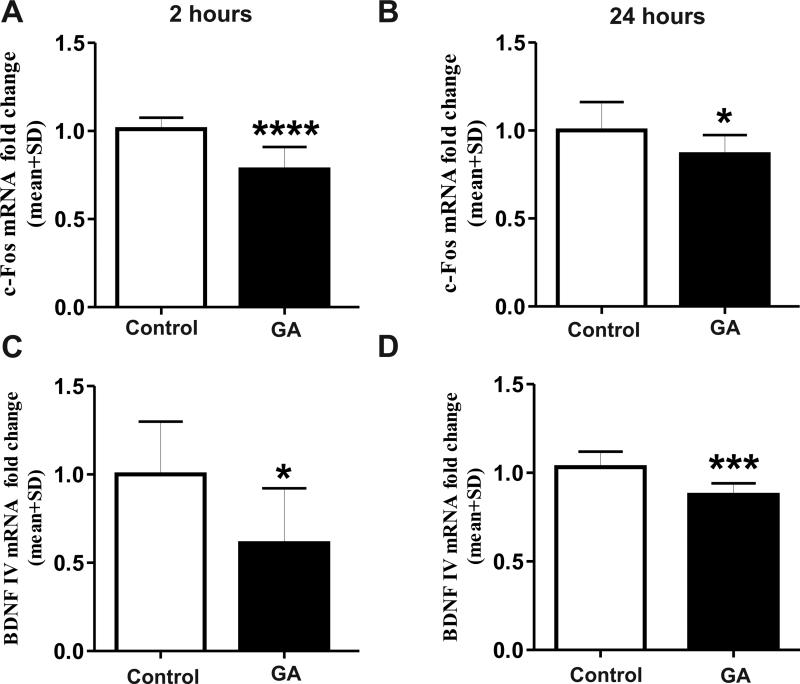

Since H3 hypoacetylation results in more condensed chromatin structure, we reasoned that GA exposure would decrease the transcription of c-Fos and BDNF genes.

To evaluate this notion we measured their mRNA expressions (Figure 8). As shown in Fig.8A, GA caused significant decrease (about 30%) in c-Fos mRNA at 2 h post-GA (Fig. 8A; ***, p=0.0001; n=10) and 24 h later (about 20%, Fig. 8B; *, p=0.025; n=12). Similarly, the expression of BDNF mRNA was decreased significantly at 2 h (about 40%, Fig. 8C; *, p=0.028; n=7-8) and at 24 h post-GA (about 20%, Fig. 8D; ***, p=0.001; n=8) compared with that in sham controls.

Figure 8. Anesthesia decreases transcription of target genes c-Fos and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the immature hippocampus.

Using real time PCR, we determined the mRNA expression of c-Fos (A and B) and BDNF (exon IV; C and D). Anesthesia exposure caused significant decrease in c-Fos mRNA at 2 h (****, p= 0.0001; n=10; A) and at 24h (*, p=0.025; n=12; B). Similarly, the expression of BDNF mRNA was significantly decreased at 2 h (*, p=0.028; n=7-8; C) and at 24 h after anesthesia (***, p=0.001; n=8; D) as compared with sham controls.

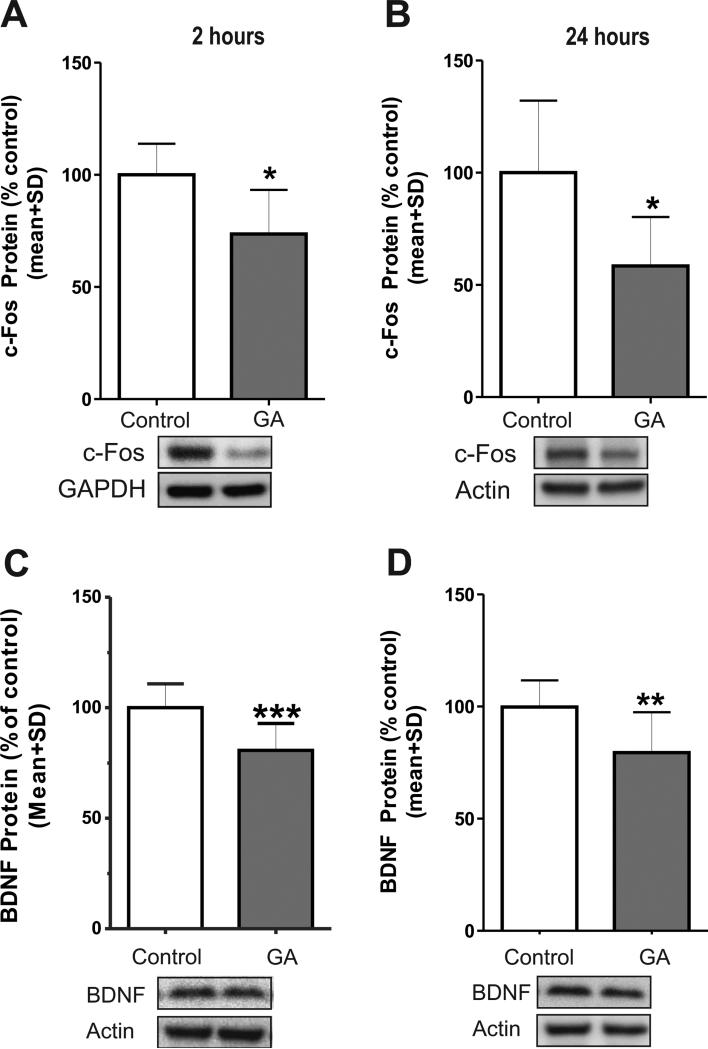

To further assess the outcomes of GA-induced H3 hypoacetylation of the target genes c-Fos and BDNF, we determined whether expression the respective proteins was decreased as well (Figure 9). We found that expression of c-Fos protein measured at 2 h (Fig. 9A, *, p=0.02; n=6) and at 24 h (Fig. 9B, *, p=0.015; n=7) post-GA was decreased significantly (approximately 35% and 40% decrease, respectively, as compared with controls). Similarly, levels of BDNF protein were down-regulated significantly both at 2 h (Fig. 9C, about 25%; ***p=0.0002; n=14) and at 24 h (Fig. 9D; **, p=0.0016; n=14) as compared with that in sham controls.

Figure 9. Anesthesia down-regulates expression of c-Fos and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) protein in the immature hippocampus.

We used Western blotting to assess the protein levels of c-Fos (A and B) and BDNF (C and D). Anesthesia caused a decrease in expression of c-Fos when measured at 2 h (A; *, p=0.02; n=6) and at 24 h (B; *, p=0.015; n=7) as compared with age-matched controls. Anesthesia causes a decrease in BDNF protein when measured at 2 h (C; ***, p=0.0002; n=14) and at 24 h (D; **, p=0.0016; n=14), as compared with aged-matched sham controls.

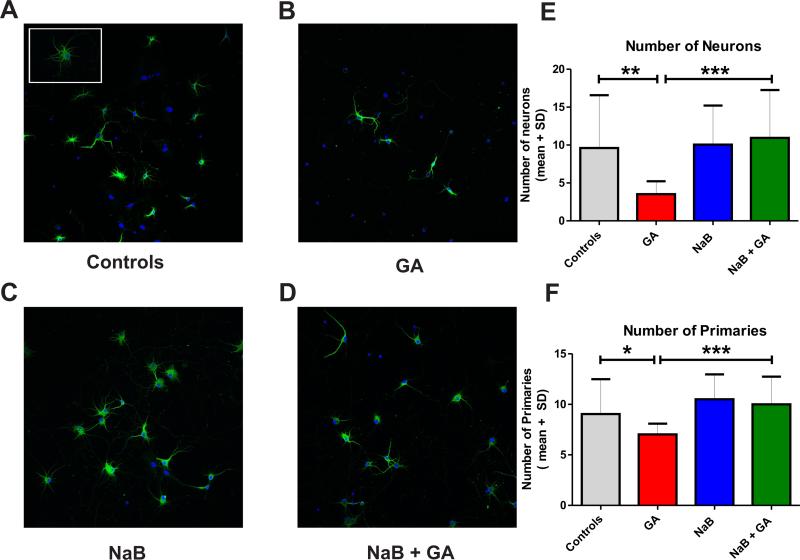

Since c-Fos and BDNF play important roles in morphological development and synaptic communication of immature neurons and since GA appears to cause epigenetic modulations of these genes, we probed two functional links between these effects. To investigate the relationship between modulation of histone acetylation and morphological changes in developing neurons, we focused on dendritic arborization, a hallmark of synaptogenesis and neuronal circuitry formation (Figure 10). For ease of studying neuronal morphology and dendritic arborization, we used our in vitro system of hippocampal neurons (see Methods). We found that at 3 days post treatment, when compared to controls (Fig. 10A; see the insert of a well-developed arboretum typical of control neurons), hippocampal cells exposed to a similar GA cocktail as in our in vivo studies (25 μg/ml midazolam, 70% nitrous oxide and 0.75% isoflurane for 24 h) exhibit significant impairment in arborization (Fig. 10B). This impairment is manifested as decreased numbers of primary branches, thus giving neurons a bipolar instead of a stellar appearance. The HDAC global inhibitor NaB (at 5 mM) had no effect alone (Fig. 10C) but when co-administered with GA, resulted in a complete abolishment of the GA-induced impairment in dendritic arborization (Fig. 10D). Quantification revealed that GA induced a significant decrease in neuronal density compared with controls (**, p=0.0028; n=15 scenes per data point; Fig. 10E), an effect that was abolished completely with NaB (GA alone vs. GA+NaB, ***, p=0.0002; n=15 neurons per data point). The quantification suggests lesser complexity of dendritic branching in GA-treated neurons (*, p=0.041; n=13-15 neurons per data point), an impairment that was completely reversed with NaB (Fig. 10F; GA alone vs. GA+NaB, ***, p=0.0005; n=15 neurons per data point; green fluorescence/MAP-2 to label neurons; red fluorescence/DAPI staining for nuclei; mag. 20x). These data suggest that GA impairs neuronal survival and morphological development and that this impairment is influenced by the state of histone acetylation. It is noteworthy, though, that the dendritic branching of cultured neurons depends not only on epigenetic influences but on intrinsic regulators as well- most notably spatial microenviromental cues and neuronal interactions which are controlled by neuronal density. Hence, our findings regarding GA-induced epigenetic effects on branching morphogenesis should be considered in view of GA-induced decrease in neuronal density.

Figure 10. Anesthesia-induced impairment of morphological development in cultured hippocampal neurons is reversed with the restoration of histone-3 acetylation status.

We used cultured hippocampal neurons from E18 rat fetuses and expose them to anesthesia (25 μg/ml midazolam, 70% nitrous oxide and 0.75% isoflurane for 24 h) at DIV 3. (A) Normal morphological appearance of hippocampal neurons in culture is typically stellar with well-developed neuronal processes forming a rich arboretum. (B) Three days post anesthesia treatment, hippocampal cells exhibit significant impairment in arborization, shown as decreased number of primary branches, thus giving neurons a bipolar instead of a stellar appearance (Fig. 10B). (C) Compared to controls the global histon deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor sodium butyrate (NaB, at 5 mM) had no effect on dendritic arborization. (D) NaB co-administered with anesthesia caused a complete abolishment of the anesthesia-induced impairment in dendritic arborization. (E) The quantification shows that anesthesia caused a significant decrease in neuronal density compared with controls (**, p=0.002; n=15 scenes per data point), an effect that was abolished completely with NaB (***, p=0.0002; n=15 scenes per data point). (F) The quantification of primary processes showed that anesthesia caused a significant decrease in the number of primary dendritic branches (*, p=0.04; n=13-15 neurons per data point), an impairment that was reversed completely with NaB (***, p=0.0005; n=15 scenes per data point) (green fluorescence, MAP-2 to label neurons; red fluorescence, DAPI staining for nuclei; mag. 20x).

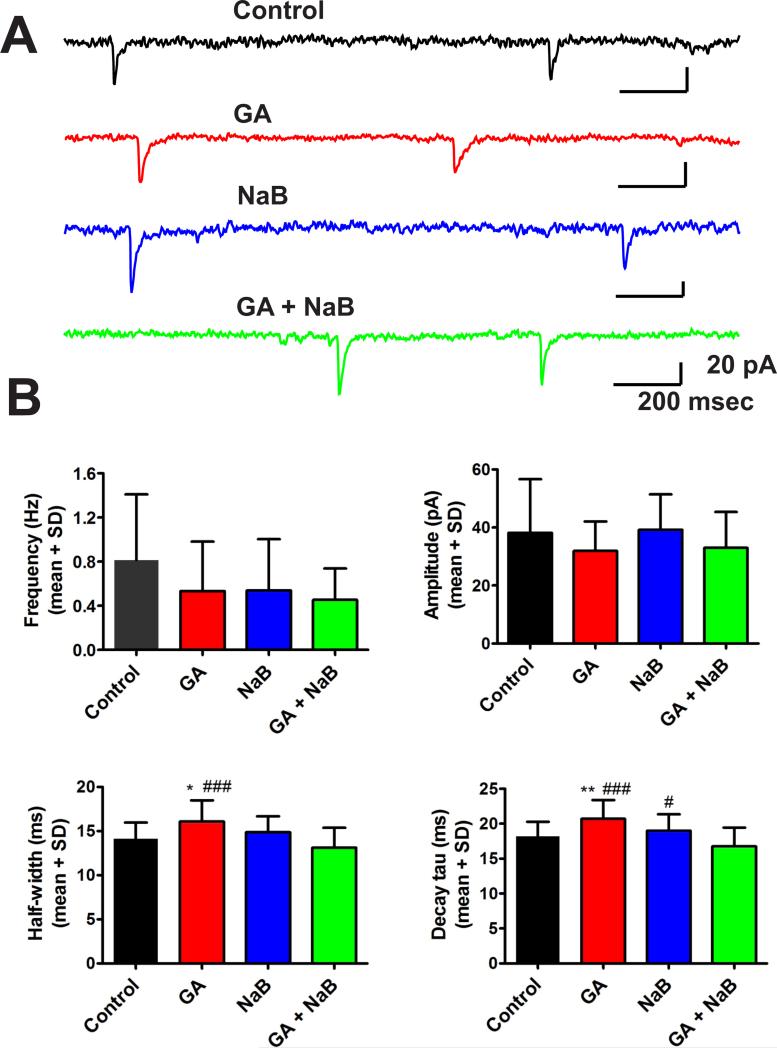

To determine whether the well-known GA-induced impairment of neuronal synaptic transmission could be restored if the histone acetylation status were restored, we made electrophysiological patch-clamp recordings of synaptic GABAA-mediated currents using hippocampal slices from P7 rat pups and cultured for up to 2 weeks.27 Slices were exposed to our routine GA protocol (25 μg/ml midazolam, 70% nitrous oxide and 0.75% isoflurane for 24 h). Miniature inhibitory post-synaptic currents (mIPSCs) were recorded in pyramidal neurons of the region comprising hippocampal CA1 and subiculum up to 10 days post-treatment (Fig. 11) in the presence of 1 μM tetrodotoxin (TTX) (to block action potentials) and 5 μM NBQX and 50 μM d-APV (to block AMPA and NMDA currents, respectively). Original traces of mIPSCs from representative hippocampal neurons in controls (black trace), GA (red trace), NaB (blue trace) and GA+NaB (green trace) experimental groups are depicted in Fig. 11A. Bar graphs showing averages from multiple experiments of the frequency, amplitude, half-width and decay of recorded mIPSCs are depicted in Figure 11B for the four groups as follows: controls (black bars, n=22 neurons), GA (red bars, n=23 neurons), NaB (blue bars, n=16 neurons) and NaB + GA (green bars, n=20 neurons). The first two parameters measured (frequency and amplitude) were not affected significantly by different treatments, as assessed by one-way ANOVA. On the other hand, one-way ANOVA revealed a significant slowing (about 15%) of current kinetics by GA treatment as compared with the control group (half-width of GA vs. controls: F(3,77)=7.64, p<0.001, and the decay time of GA vs. controls: F(3,77)=9.47, p<0.001). The post hoc analysis further revealed that these parameters were increased significantly in neurons exposed to GA compared with the sham group (*, p=0.014 and **, p=0.006, respectively), suggesting alterations in postsynaptic GABAA receptor-mediated currents. Importantly, NaB had no significant effect when applied alone, yet the addition of NaB to GA reversed the half-width and the decay time values to the control level, as evidenced by comparison to the sham group (p=0.383 and p=0.251, respectively) and GA alone (***, p<0.001 for both parameters).

Figure 11. Anesthesia-induced impairment of inhibitory synaptic neurotransmission in hippocampal slice cultures is reversed with the restoration of histone-3 acetylation status.

(A) Representative sample of original miniature inhibitory post-synaptic currents (mIPSC) traces from controls- (black), general anesthesia (GA)- (red), sodium butyrate (NaB)- (blue) and GA+NaB-treated (green) hippocampal neurons. (B) Plots describing frequency, amplitude, half-width and decay tau of all mIPSC events in the following groups: black bars (controls, n=22 neurons), red bar (GA, n=23 neurons), blue bars (NaB, n=16 neurons) and green bars (NaB+GA, n=20 neurons). All symbols represent means ± SD; *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01 vs. controls; #, p<0.05; ###, p<0.001 vs. GA+NaB, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test.

In studies of action potential-independent miniature synaptic events, it is generally accepted that any changes in the frequency of events reflect presynaptic mechanisms whereas alterations of event amplitudes and/or kinetics usually reflect postsynaptic mechanisms. Hence our data suggest that GA alters postsynaptic neurotransmission and that this alteration is influenced by the state of histone acetylation.

Discussion

Exposure of the immature brain to GA during critical stages of synaptogenesis causes substantial epigenetic modulations manifested as H3 hypoacetylation and impairment of CBP activity resulting in down-regulated expression of the important target genes BDNF and c-Fos. Reversal of histone hypoacetylation with the global HDAC inhibitor NaB improves GA-induced morphological and functional impairments of neuronal development and synaptic communication. These findings suggest that GA-induced epigenetic modulations could be responsible for the long-term impairments of neuronal development and synaptic communication that we and others have been reporting for over a decade.

Activity-dependent transcription is the mechanism by which neurons convert brief cellular changes into stable alterations in brain function that constitute a form of ‘molecular memory’.32 Enzymatic modifications (e.g. acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation) of amino acids in the N-terminus of histones lead to dramatic changes in chromatin structure.33 Our findings suggest that GA exposure causes H3 hypoacetylation of N-terminal lysines, an epigenetic change known to result in the condensed conformation of chromatin less conducive to transcription.34 We show that the transcription of two target genes of interest, BDNF and c-Fos, was indeed decreased by GA, a change that occurred at least in part due to histone hypoacetylation in their promotor regions. Conversely, it has been shown that the up-regulation of histone acetylation by inhibition of HDAC enzymes (which remove acetyl groups from lysines on histone tails) increases the expression of genes critical for memory formation (BDNF in particular).13

Histone acetylation levels are determined by a balance of the activities of histone acetyl transferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), each family comprised of several isoforms.35 Although our study was not designed to scrutinize GA-induced effects on each isoform, we show that GA does not have an overall effect on the activity of the HDAC family. Hence, we think that hypoacetylation most likely is caused by GA-induced down-regulation of CBP, the best characterized HAT33 and a co-activator of the transcription factor CREB. CBP targets BDNF and c-Fos promoters and facilitates their transcription a) via acting as a scaffolding protein interacting directly with components of the RNA polymerase II complex and recruiting them to the gene promoter, and b) via its intrinsic HAT activity, which results in chromatin relaxation.9 Thus, CBP is a link between epigenetic mechanisms and classic gene regulatory mechanisms. CREB and CBP are regulated by neuronal activity and their interaction is critical for transcription of genes essential for brain development. We suggest that GA-induced down-regulation of CBP expression and its HAT activity results in H3 hypoacetylation in the promoter regions of target genes BDNF and c-Fos, which in turn inhibits their transcription.

Interestingly, our data suggest that down-regulation of CBP protein expression most likely is caused by CBP degradation to fragments having impaired HAT activity.36 Although the exact mechanism of CBP fragmentation remains to be determined, activation of apoptotic cascades, in particular, the activation of caspase-6, was shown to increase CBP cleavage, suggesting that CBP is very sensitive to apoptotic activation.37 Considering that GA exposure during critical stages of synaptogenesis results in massive apoptotic activation as shown previously1 and increase in fragmentation of lamin (Fig. 4), a substrate of activated caspase-6, it is reasonable to propose that GA-induced CBP fragmentation during critical stages of synaptogenesis might be an apoptosis-induced phenomenon. Excessive CBP fragmentation has been implicated in Alzheimer's disease and was reported to promote amyloid accumulation.37

It is noteworthy that a similar decrease in CBP protein expression also has been reported in heterozygous CBP mutant mice, which have significantly reduced content of acetylated histones and prominent learning deficits.38 It is intriguing and worrisome that a single exposure to GA during critical stages of synaptogenesis could mimic epigenetic changes observed in CBP mutant mice.

Modulation of neuronal activity impacts several kinase pathways that drive c-Fos and CREB phosphorylation, thus controlling their interaction with CBP and leading to transcriptional activation or inhibition at specific promoters. Both c-Fos and CREB are exquisitely sensitive to changes in neuronal activity, and CREB is the best understood of the transcription factors that regulate changes in gene expression necessary for acquisition and storage of new memories.14,15 Our data show that the triple anesthetic cocktail causes significant down-regulation of c-Fos and CREB proteins in developing hippocampus, and suggest that this effect may be mediated via modulation of neuronal activity. We found that GA increased the Ser-133-phosphorylated (activated) fraction of CREB. Although surprising considering GA-induced epigenetic changes, our observation is similar to one made by Barrett and colleagues39 regarding CREB activation accompanying down-regulated CBP expression. They showed that neurons lacking CBP maintained phosphorylation of the transcription factor CREB, yet failed to activate CREB/CBP-mediated gene expression. It is possible that the phosphorylation of CREB is maintained in an attempt to compensate for GA-induced decrease in CBP content and activity.

HDAC inhibitors have been used in attempt to increase or ‘normalize’ histone acetylation and relax chromatin structure to improve access to transcription factors and, thus, lead to increased gene transcription.40,41 We used the global HDAC inhibitor NaB, which crosses the blood-brain barrier42,43 but does not have particular specificity for any of the HDAC isoforms, in a proof-of-concept experiment to argue that GA-induced histone hypoacetylation, and consequent impairment in neuronal development and synaptic neurotransmission, could be reversed with restoration of H3 acetylation. It is noteworthy that NaB also exhibits other biological effects such as anti-inflammatory44-46 and neuroprotective effects;45,46 it may stabilize the blood-brain barrier after a stroke45 and also was shown to stimulate neurogenesis.47 Hence, further studies are needed to scrutinize the role of isoform-specific and more selective HDAC inhibitors in reversing GA-induced histone hypoacetylation.

Epigenetic changes are critical for long-term memory storage.12,13 For instance, the down-regulation of CBP protein together with significant reduction in histone acetylation were accompanied by impaired late phase hippocampal long-term potentiation and learning deficits35,38,48 similar to those described post-GA exposure1. Furthermore, CBP mutations have been shown to result in reduced CBP protein content and in histone acetylation accompanied by impaired late phase hippocampal long-term potentiation and learning deficits.38,39,48 Considering that early exposure to GA causes significant impairment in dendritic arborization, a morphological substrate for the formation of neuronal connections and synaptogenesis, and that it jeopardizes the survival of existing dendritic spines and synapses as well as the formation of new ones,19, 49-51 our findings with NaB suggest that histone hypoacetylation is an important factor in functional impairments of synaptic neurotransmission in developing hippocampus.4 Indeed, they suggest that GA alters presynaptic neurotransmission and that this alteration is influenced by the state of histone acetylation. Since GABAA currents represent the main excitatory drive in developing hippocampal neurons,52 we suggest that GA-induced slowing of mIPSC kinetics could induce lasting and perhaps excessive depolarization that could hamper brain development and, in part, explain observed impairments in long-term potentiation we have reported previously.1

Many epigenetic changes can be detected long after the initial environmental or pharmacological influences are removed. However, c-Fos and BDNF belong to the immediate early gene family and undergo very rapid epigenetic modifications53,54 necessitating an early analysis of the histone acetylation status of their respective promotors (in particular at the CREB binding site), as we have done in this study. Despite the rapid (and in several models, transient) epigenetic changes in c-Fos and BDNF promotors, these modulations have long-lasting influence via the activator protein (AP)-1 complex and AP-1 binding region on promoters of numerous later response genes that participate in processes crucial for neuronal development and survival.55

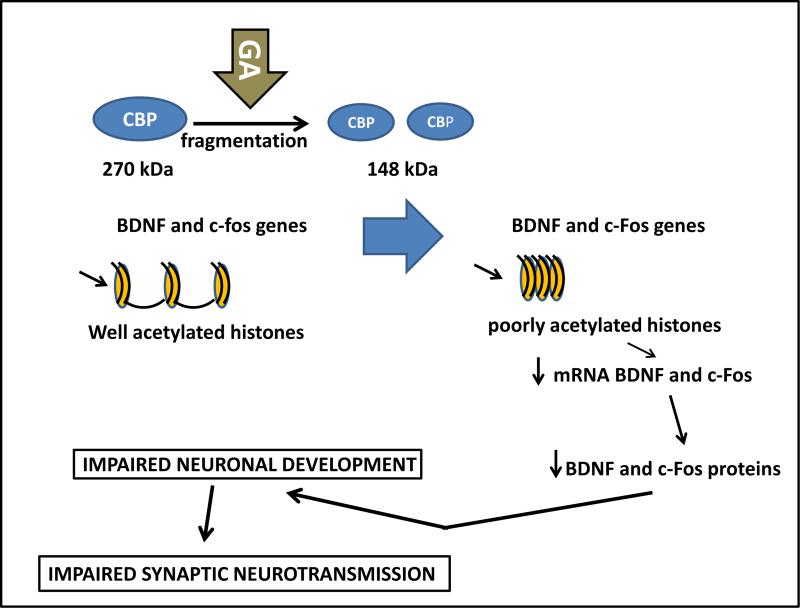

Based on our findings, we propose a cascade of events initiated by GA-induced epigenetic modulations (Fig. 12). By promoting CBP degradation, GA induces significant down-regulation of full length CBP protein, which results in a decrease in its HAT activity. This, in turn, causes H3 hypoacetylation, an epigenetic change that leads to more condensed chromatin structure less conducive to transcription of the target genes BDNF and c-Fos. Inhibition of c-Fos and of BDNF transcription has been shown to involve changes in chromatin structure brought about by post-translational histone modification similar to the ones we report here56-58. BDNF and c-Fos are critical for cognitive development;56,59 they modulate the strength of existing synaptic connections, act in the formation of new synaptic contacts56,60,61 and are modulated by an early exposure to GA.49,62,63

Figure 12. Proposed cascade of epigenetic events responsible for anesthesia-induced neurotoxicity during critical stages of synaptogenesis.

Anesthesia promotes excessive cAMP-responsive element binding protein (CBP) degradation (fragmentation from 270 kDa to 148 kDa) thus down-regulating full length CBP protein with consequent decrease of its histone acetylase (HAT) activity. This decreased HAT activity, in turn, causes histone-3 hypoacetylation, an epigenetic change that leads to more condensed chromatin structure less conducive to transcription of the target genes brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and c-Fos. BDNF and c-Fos are critical for neuronal morphological development. An impairment in proper dendritic arborization leads to impaired neuronal connectivity resulting in faulty formation of neuronal circuities and compromised synaptic neurotransmission.

Our anesthesia protocol, a reliable model for studying developmental neurodegeneration, uses several anesthetics in combination, as is done in clinical anesthesia. Therefore, we are unable to assign the relative contribution of each agent to the epigenetic modulations we describe. Further studies with individual anesthetics may help to decipher their relative importance; however, their promiscuous nature still may hamper our ability to discern the specific mechanisms that may be important in epigenetic modulations.

In conclusion, we show that exposure to GA during critical stages of synaptogenesis results in significant epigenetic modulations manifested as post- translational modification of H3 acetylation status. Although still unconfirmed, it is reasonable to propose that long-lasting1,64 and transgenerational8 impairments in cognitive development reported after an early exposure to GA could be caused by the epigenetic changes.

Box Summary.

What we already know about this topic

Exposure of rodents to general anesthesia in utero causes cognitive impairments not only in the first generation offspring, but also in the second generation offspring born to dams exposed to general anesthesia in utero.

What this article tells us that is new

Exposure to general anesthesia during critical stages of synaptogenesis modulated expression and function of the key transcription factors, cAMP-responsive element binding (CREB) protein binding protein (CBP) and CREB.

CBP and CREB modulation may, in turn, cause epigenetic changes manifested as histone hypoacetylation, leading to down-regulated transcription of the target genes c-Fos and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which play an important role in neuronal development.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Health/ The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child and Human Development (NIH/NICHD) R0144517 (to Vesna Jevtovic-Todorovic), and R0144517-S (to Vesna Jevtovic-Todorovic), Bethesda, MD, USA; Harold Carron endowment (to Vesna Jevtovic-Todorovic), John E. Fogarty Award 007423-128322 (to Vesna Jevtovic-Todorovic), National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; and March of Dimes National Award, USA (to Vesna Jevtovic-Todorovic) and NIH/NIGMS R01 GM102525 (to Slobodan Todorovic). Vesna Jevtovic-Todorovic was an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association, National Award, USA. Guangfu Wang was supported in part by a postdoctoral fellowship (no. 310443) from the Epilepsy Foundation.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Hartman RE, Izumi Y, Benshoff ND, Dikranian K, Zorumski CF, Olney JW, Wozniak DF. Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. J Neurosci. 2003;23:876–882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00876.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yon J-H, Daniel-Johnson J, Carter LB, Jevtovic-Todorovic V. Anesthesia induces neuronal cell death in the developing rat brain via the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways. Neuroscience. 2005;35:815–827. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yon J-H, Carter LB, Reiter RJ, Jevtovic-Todorovic V. Melatonin reduces the severity of anesthesia-induced apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;21:522–530. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanchez V, Feinstein SD, Lunardi N, Joksovic PM, Boscolo A, Todorovic SM, Jevtovic-Todorovic V. General Anesthesia Causes Long-term Impairment of Mitochondrial Morphogenesis and Synaptic Transmission in Developing Rat Brain. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:992–1002. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182303a63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilder RT, Flick RP, Sprung J, Katusic SK, Barbaresi WJ, Mickelson C, Gleich SJ, Schroeder DR, Weaver AL, Warner DO. Early exposure to anesthesia and learning disabilities in a population-based birth cohort. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:796–804. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000344728.34332.5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Block RI, Thomas JJ, Bayman EO, Choi JY, Kimble KK, Todd MM. Are anesthesia and surgery during infancy associated with altered academic performance during childhood? Anesthesiology. 2012;117:494–503. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182644684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ing CH, DiMaggio CJ, Malacova E, Whitehouse AJ, Hegarty MK, Feng T, Brady JE, von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Davidson AJ, Wall MM, Wood AJ, Li G, Sun LS. Comparative analysis of outcome measures used in examining neurodevelopmental effects of early childhood anesthesia exposure. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:1319–32. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chalon J, Tang CK, Ramanathan S, Eisner M, Katz R, Turndorf H. Exposure to halothane and enflurane affects learning function of murine progeny. Anesth Analg. 1981;60:794–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo W, Crossey EL, Zhang L, Zucca S, George OL, Valenzuela CF, Zhao X. Alcohol exposure decreases CREB binding protein expression and histone acetylation in the developing cerebellum. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pascual M, Do Couto BR, Alfonso-Loeches S, Aguilar MA, Rodriguez-Arias M, Guerri C. Changes in histone acetylation in the prefrontal cortex of ethanol-exposed adolescent rats are associated with ethanol-induced place conditioning. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:2309–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murawski NJ, Klintsova AY, Stanton ME. Neonatal alcohol exposure and the hippocampus in developing male rats: effects on behaviorally induced CA1 c-Fos expression, CA1 pyramidal cell number, and contextual fear conditioning. Neuroscience. 2012;206:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lubin FD, Roth TL, Sweatt JD. Epigenetic regulation of BDNF gene transcription in the consolidation of fear memory. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10576–10586. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1786-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stafford JM, Lattal KM. Is an epigenetic switch the key to persistent extinction? Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011;96:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kida S, Josselyn SA, Peña de Ortiz S, Kogan JH, Chevere I, Masushige S, Silva AJ. CREB required for the stability of new and reactivated fear memories. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:348–55. doi: 10.1038/nn819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pittenger C, Huang YY, Paletzki RF, Bourtchouladze R, Scanlin H, Vronskaya S, Kandel ER. Reversible inhibition of CREB/ATF transcription factors in region CA1 of the dorsal hippocampus disrupts hippocampus-dependent spatial memory. Neuron. 2002;34:447–62. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00684-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubinstein JH, Taybi H. Broad thumbs and toes and facial abnormalities: A possible mental retardation syndrome. Am J Dis Child. 1963;105:588–608. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1963.02080040590010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petrij F, Giles RH, Dauwerse HG, Saris JJ, Hennekam RC, Masuno M, Tommerup N, van Ommen GJ, Goodman RH, Peters DJ, Breuning MH. Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome caused by mutations in the transcriptional co-activator CBP. Nature. 1995;376:348–51. doi: 10.1038/376348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaliszewska A, Kossut M. Npas4 expression in two experimental models of the barrel cortex plasticity. Neural Plast. 2015;2015:175701. doi: 10.1155/2015/175701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lunardi N, Ori C, Erisir A, Jevtovic-Todorovic V. General anesthesia causes long-lasting disturbances in the ultrastructural properties of developing synapses in young rats. Neurotox Res. 2010;17:179–88. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9088-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanders RD, Xu J, Shu Y, Januszewski A, Halder S, Fidalgo A, Sun P, Hossain M, Ma D, Maze M. Dexmedetomidine attenuates isoflurane-induced neurocognitive impairment in neonatal rats. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:1077–85. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819daedd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vutskits L, Gascon E, Potter G, Tassonyi E, Kiss JZ. Low concentrations of ketamine initiate dendritic atrophy of differentiated GABAergic neurons in culture. Toxicology. 2007;234:216–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goslin K, Asmussen H, Banker G. Rat hippocampal neurons in low-density culture. In: Banker G, Goslin K, editors. Culturing Nerve Cells. 2nd ed. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1998. pp. 339–70. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim CS, Hoang ET, Viar KE, Stornetta RL, Scott MM, Zhu JJ. Pharmacological rescue of Ras signaling, GluA1-dependent synaptic plasticity, and learning deficits in a fragile X model. Genes & Development. 2014;28:273–289. doi: 10.1101/gad.232470.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qin Y, Zhu Y, Baumgart JP, Stornetta RL, Seidenman K, Mack V, van Aelst L, Zhu JJ. State-dependent Ras signaling and AMPA receptor trafficking. Genes & Development. 2005;19:2000–2015. doi: 10.1101/gad.342205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar A, Choi K-H, Renthal W, Tsankova NM, Theobald DEH, Truong H-T, Russo SJ, LaPlant Q, Sasaki TS, Whistler KN, Neve RL, Self DW, Nestler EJ. Chromatin remodeling is a key mechanism underlying cocaine-induced plasticity in striatum. Neuron. 2005;48:303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(T) (–delta delta C) method. Methods. 2011;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCormack SG, Stornetta RL, Zhu JJ. Synaptic AMPA receptor exchange maintains bidirectional plasticity. Neuron. 2006;50:75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levenson JM, O'Riordan KJ, Brown KD, Trinh MA, Molfese DL, Sweatt JD. Regulation of histone acetylation during memory formation in the hippocampus. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40545–59. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402229200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peleg S, Sananbenesi F, Zovoilis A, Burkhardt S, Bahari-Javan S, Agis-Balboa RC, Cota P, Wittnam JL, Gogol-Doering A, Opitz L, Salinas-Riester G, Dettenhofer M, Kang H, Farinelli L, Chen W, Fischer A. Altered histone acetylation is associated with age-dependent memory impairment in mice. Science. 2010;328:753–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1186088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itzhak Y, Liddie S, Anderson KL. Sodium butyrate-induced histone acetylation strengthens the expression of cocaine-associated contextual memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2013;102:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardingham GE, Arnold FJ, Bading H. A calcium microdomain near NMDA receptors: on switch for ERK-dependent synapse-to-nucleus communication. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:565–566. doi: 10.1038/88380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robinson AJ, Nestler EJ. Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction. Nature Neuroscience. 2011;12:623–637. doi: 10.1038/nrn3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rudenko A, Tsai LH. Epigenetic modifications in the nervous system and their impact upon cognitive impairments. Neuropharmacology. 2014;80:70–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrett RM, Wood MA. Beyond transcription factors: the role of chromatin modifying enzymes in regulating transcription required for memory. Learn Mem. 2008;15:460–7. doi: 10.1101/lm.917508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen WF, Krishnan K, Lawrence HJ, Largman C. The HOX homeodomain proteins block CBP histone acetyltransferase activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(21):7, 509–22. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7509-7522.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rouaux C, Jokic N, Mbebi C, Boutillier S, Loeffler JP, Boutillier AL. Critical loss of CBP/p300 histone acetylase activity by caspase-6 during neurodegeneration. EMBO J. 2003;22:6537–49. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Korzus E, Rosenfeld MG, Mayford M. CBP histone acetyltransferase activity is a critical component of memory consolidation. Neuron. 2004;42:961–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barrett RM, Malvaez M, Kramar E, Matheos DP, Arrizon A, Cabrera SM, Lynch G, Greene RW, Wood MA. Hippocampal focal knockout of CBP affects specific histone modifications, long-term potentiation and long-term memory. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1545–56. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gurvich OL, Baranov PV, Gesteland RF, Atkins JF. Expression levels influence ribosomal frameshifting at the tandem rare arginine codons AGG_AGG and AGA_AGA in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:4023–32. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.12.4023-4032.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Machado-Vieira R, Ibrahim L, Zarate CA., Jr Histone deacetylases and mood disorders: epigenetic programming in gene-environment interactions. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2011;17:699–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00203.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grayson DR, Kundakovic M, Sharma RP. Is there a future for histone deacetylase inhibitors in the pharmacotherapy of psychiatric disorders? Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77:126–35. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.061333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minamiyama M, Katsuno M, Adachi H, Waza M, Sang C, Kobayashi Y, Tanaka F, Doyu M, Inukai A, Sobue G. Sodium butyrate ameliorates phenotypic expression in a transgenic mouse model of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1183–92. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huuskonen J, Suuronen T, Nuutinen T, Kyrylenko S, Salminen A. Regulation of microglial inflammatory response by sodium butyrate and short-chain fatty acids. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:874–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim HJ1, Rowe M, Ren M, Hong JS, Chen PS, Chuang DM. Histone deacetylase inhibitors exhibit anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects in a rat permanent ischemic model of stroke: multiple mechanisms of action. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:892–901. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.120188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berni Canani R, Di Costanzo M, Leone L. The epigenetic effects of butyrate: potential therapeutic implications for clinical practice. Clin Epigenetics. 2012;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1868-7083-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chuang DM, Leng Y, Marinova Z, Kim HJ, Chiu CT. Multiple roles of HDAC inhibition in neurodegenerative conditions. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:591–601. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Valor LM, Pulopulos MM, Jimenez-Minchan M, Olivares R, Lutz B, Barco A. Ablation of CBP in forebrain principal neurons causes modest memory and transcriptional defects and a dramatic reduction of histone acetylation but does not affect cell viability. J Neurosci. 2011;31:1652–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4737-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Head BP, Patel HH, Niesman IR, Drummond JC, Roth DM, Patel PM. Inhibition of p75 neurotrophin receptor attenuates isoflurane-mediated neuronal apoptosis in the neonatal central nervous system. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:813–25. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819b602b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Briner A, De Roo M, Dayer A, Muller D, Habre W, Vutskits L. Volatile anesthetics rapidly increase dendritic spine density in the rat medial prefrontal cortex during synaptogenesis. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:546–56. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181cd7942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Briner A, Nikonenko I, De Roo M, Dayer A, Muller D, Vutskits L. Developmental Stage-dependent persistent impact of propofol anesthesia on dendritic spines in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:282–93. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318221fbbd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pfeffer CK, Stein V, Keating DJ, Maier H, Rinke I, Rudhard Y, Hentschke M, Rune GM, Jentsch TJ, Hübner CA. NKCC1-dependent GABAergic excitation drives synaptic network maturation during early hippocampal development. J Neurosci. 2009;29(11):3419–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1377-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kwon B, Houpt TA. Phospho-acetylation of histone H3 in the amygdala after acute lithium chloride. Brain Res. 2010;1333:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hendrickx A, Pierrot N, Tasiaux B, Schakman O, Kienlen-Campard P, De Smet C, Octave JN. Epigenetic regulations of immediate early genes expression involved in memory formation by the amyloid precursor protein of Alzheimer disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sung YJ, Wu F, Schacher S, Ambron RT. Synaptogenesis regulates axotomy-induced activation of c-Jun-activator protein-1 transcription. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6439–49. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1844-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reul JM. Making memories of stressful events: a journey along epigenetic, gene transcription, and signaling pathways. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:5. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang Y, Doherty JJ, Dingledine R. Altered histone acetylation at glutamate receptor 2 and brain-derived neurotrophic factor genes is an early event triggered by status epilepticus. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8422–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08422.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsankova NM, Berton O, Renthal W, Kumar A, Neve RL, Nestler EJ. Sustained hippocampal chromatin regulation in a mouse model of depression and antidepressant action. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:519–25. doi: 10.1038/nn1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lu Y, Christian K, Lu B. BDNF: a key regulator for protein synthesis-dependent LTP and long-term memory? Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;89:312–23. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thoenen H. Neurotrophins and neuronal plasticity. Science. 1995;270:593–598. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lu B, Figurov A. Role of neurotrophins in synapse development and plasticity. Rev Neurosci. 1997;8:1–12. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.1997.8.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lu LX, Yon JH, Carter LB, Jevtovic-Todorovic V. General anesthesia activates BDNF-dependent neuroapoptosis in the developing rat brain. Apoptosis. 2006;11:1603–15. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-8762-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kidambi S, Yarmush J, Berdichevsky Y, Kamath S, Fong W, Schianodicola J. Propofol induces MAPK/ERK cascade dependant expression of c-Fos and Egr-1 in rat hippocampal slices. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:201. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boscolo A, Starr JA, Sanchez V, Lunardi N, DiGruccio MR, Ori C, Erisir A, Trimmer P, Bennett J, Jevtovic-Todorovic V. The abolishment of anesthesia-induced cognitive impairment by timely protection of mitochondria in the developing rat brain: the importance of free oxygen radicals and mitochondrial integrity. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;45:1031–41. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]