Abstract

Elongator protein 3 (Elp3) is the enzymatic unit of the elongator protein complex, a histone acetyltransferase complex involved in transcriptional elongation. It has long been shown to play an important role in cell migration; however, the underlying mechanism is unknown. Here, we showed that Elp3 is expressed in pre-migratory and migrating neural crest cells in Xenopus embryos, and knockdown of Elp3 inhibited neural crest cell migration. Interestingly, Elp3 binds Snail1 through its zinc-finger domain and inhibits its ubiquitination by β-Trcp without interfering with the Snail1/Trcp interaction. We showed evidence that Elp3-mediated stabilization of Snail1 was likely involved in the activation of N-cadherin in neural crest cells to regulate their migratory ability. Our findings provide a new mechanism for the function of Elp3 in cell migration through stabilizing Snail1, a master regulator of cell motility.

Elongator protein 3 (Elp3) is the catalytic subunit of the Elongator complex that is involved in transcriptional elongation. Elp3 facilitates RNA polymerase II transcription through the acetylation of the N-terminal tail of histone H3. Elp3 contains a C-terminal histone acetyltransferase (HAT) domain that is essential for the ability of the Elongator to acetylate histones in vitro1,2. In addition to its role in transcriptional elongation, Elp3 is involved in many other biological processes. For example, Saccharomyces cerevisiae Elp3 was shown to modulate transcriptional silencing and modulate DNA repair3. In Drosophila neurons, Elp3-dependent acetylation of Bruchpilot, an ELKS family member, is required for the regulation of the structure of presynaptic densities and neurotransmitter release efficiency4. In mouse neurons, Elp3 is found to regulate cell motility and motor-based trafficking via the acetylation of α-tubulin5. Interestingly, Elp3 was also reported to be involved in the regulation of cell migration6, and depletion of Elp3 leads to the decreased migratory ability of melanoma-derived cells7. However, the underlying mechanism of Elp3 to regulate cell migration remains elusive. Elp3 also contains an N-terminal radical S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) binding domain and has been reported to be involved in DNA demethylation8.

Neural crest cells have been a classical model to study cell migration in vivo9. Neural crest cells are induced along the border between the neural and non-neural ectoderm by the interplay of several signaling pathways, including BMP (bone morphogenetic protein), FGF (fibroblast growth factor) and Wnt (Wingless-type protein)10. After induction and specification, neural crest cells undergo an epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), delaminate from neighboring tissues and migrate throughout the embryo, producing various derivatives, including craniofacial bone and cartilage, pigment cells, glia and neurons of the periphery neural system, to name a few11. The EMT of neural crest cells is regulated by a group of evolutionarily conserved transcription factors, including Snail1 (Snail), Snail2 (Slug), and Twist112,13, which modulate cell-cell adhesion and cell polarity to enable the cells to delaminate, accomplish EMT and ensure proper migration.

The zinc-finger transcription repressor Snail1 is a key regulator of EMT that represses the expression of epithelium-specific adherent proteins such as E-cadherin, Muc1, Claudin, and Occludin14. However, Snail1 can also act as an activator to stimulate mesenchymal gene transcription15. Especially, CREB-binding protein (CBP) has been shown to acetylate Snail1 and prevent repressor complex formation, facilitating the transactivator function of Snail116.

Snail1 is crucial for neural crest migration during embryonic development and has been implicated in the EMT associated with tumor progression17,18,19,20. Due to its critical role in development and tumor metastasis, the expression of Snail1 is finely controlled at both the transcriptional and protein levels. The Snail1 protein is labile with a half-life of approximately 25 minutes21. The stability of Snail1 is regulated by several ubiquitin E3 ligases, including β-Trcp1, Fbxl14/Fbxl5 and Mdm222. Snail1 phosphorylation in the central domain by glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) promotes β-Trcp-mediated protein ubiquitination and degradation21. Fbxl14 and Fbxl5 are two F-box ubiquitin ligases involved in Snail1 degradation. During hypoxia, the expression of Fbxl14 and Fbxl5 is down-regulated, and Snail1 becomes stabilized22. Snail1 protein stability is also controlled by inflammatory cytokines through the activation of NF-κB, which then induces the expression of COP9 signalosome 2 (CSN2) to prevent the interaction of Snail1 with GSK-3β/β-Trcp23.

Here, we show that knockdown of Elp3 inhibits neural crest cell migration in Xenopus embryos. Elp3 binds Snail1 through its zinc-finger domain and inhibits its ubiquitination by β-Trcp. We show evidence that Elp3-mediated stabilization of Snail1 is likely involved in the activation of N-cadherin in neural crest cells to regulate their migratory ability.

Results

Elp3 is required for neural crest migration in Xenopus

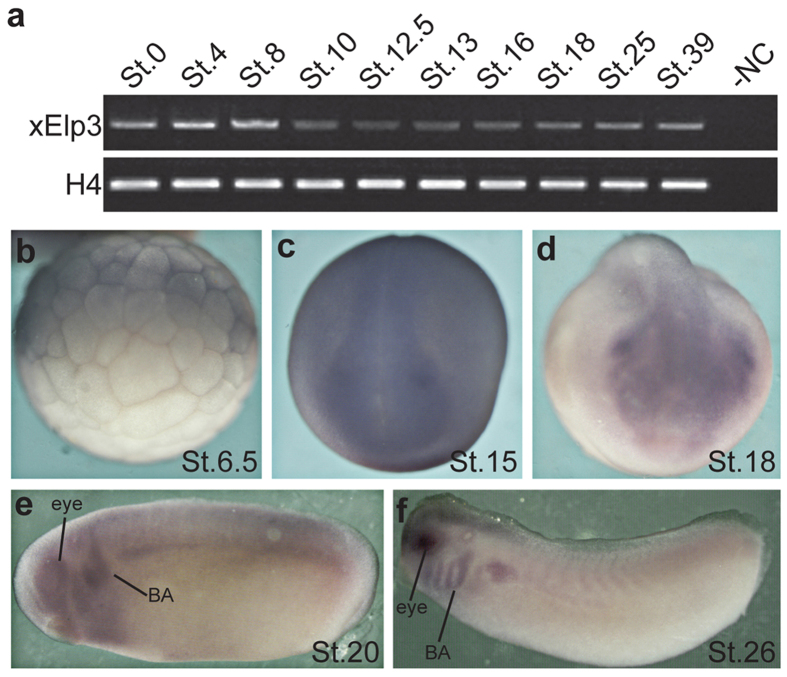

We investigated the expression pattern of Elp3 in Xenopus laevis embryos at various stages. RT-PCR results indicated that xElp3 is maternally expressed, and the expression is maintained throughout the stages that we examined (Fig. 1a). By in situ hybridization, xElp3 transcripts were detected at the animal pole of stage 6.5 embryos (Fig. 1b). Subsequently, xElp3 was expressed in the neural plate region (Fig. 1c) and then in the migrating cranial neural crest territory (Fig. 1d). At stages 20 and 26, xElp3 was detected in the branchial arches, eyes, and prospective brain region (Fig. 1e,f).

Figure 1. Expression of the Elp3 during early Xenopus development.

(a) RT-PCR analysis of Elp3 expression at different stages (St.0 to St.39). (b–f). Whole-mount in situ hybridization of xElp3. Elp3 transcript is detected in the animal pole at St.6.5 (b, lateral view, animal pole to the top). At St.15, Elp3 is expressed at the anterior neural plate and its border (c, dorsal view, anterior to the bottom), and at the late neurulation, Elp3 is most abundant in cranial neural crest (d, frontal view, dorsal to the top). At tailbud stage, Elp3 is mainly expressed in the branchial arches (BA) and eyes (e,f).

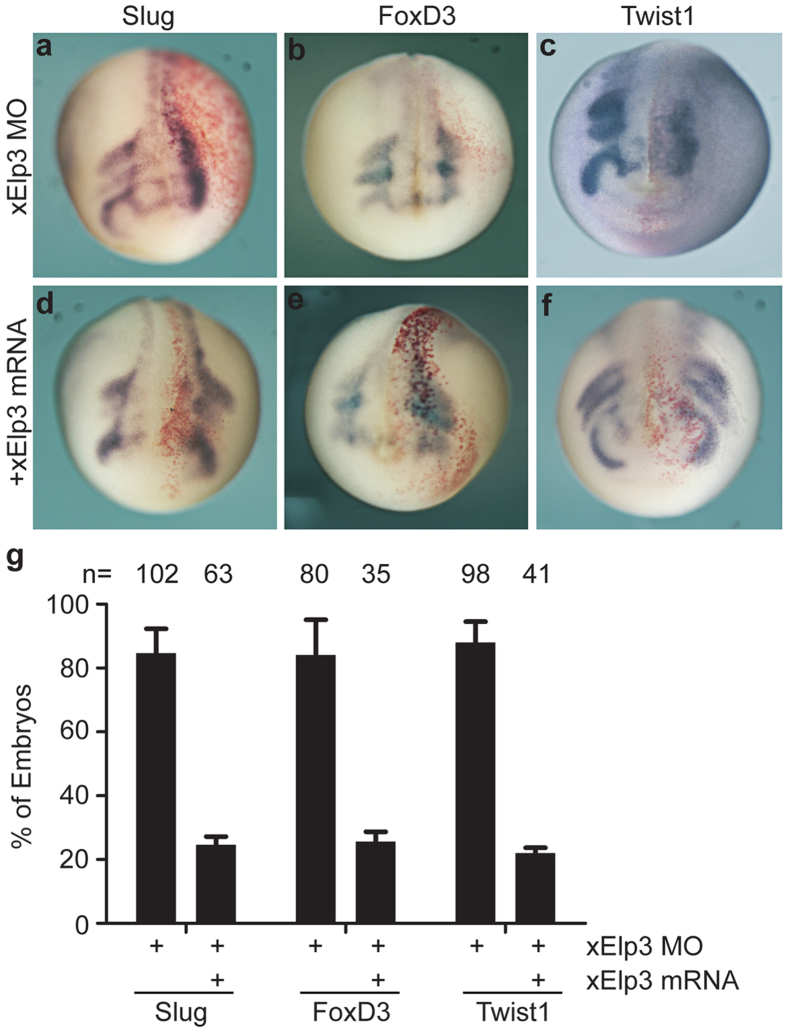

To study the potential role of Elp3 in Xenopus neural crest development, we used specific morpholino (MO) to block the expression of endogenous Elp3. The MO efficiently blocked the expression of a GFP reporter mRNA harboring the Elp3 target sequence (data not shown). When probed with the neural crest-specific markers Slug, FoxD3 and Twist1, we found that the neural crest cells failed to migrate away from the medial region on the MO-injected side (Fig. 2a–c,g). Co-injection of Xenopus Elp3 mRNA restored the migratory property of neural crest cells in the Elp3 morphants, confirming the specificity of the Elp3 morpholino (Fig. 2d–f,g).

Figure 2. Knockdown of Elp3 inhibits cranial neural crest migration in Xenopus.

(a–f) Elp3 MO (25 ng) with or without Elp3 mRNA (0.2 ng) was injected into one cell of four-cell-stage embryos, and whole-mount in situ hybridization with probes for neural crest markers was processed at St.19–21. LacZ mRNA was co-injected to trace the injected sides (stained red on the right sides). (g) Percentages of embryos with reduced migration of neural crest as shown in (a–f). The results are from three independent experiments (error bars represent SDs).

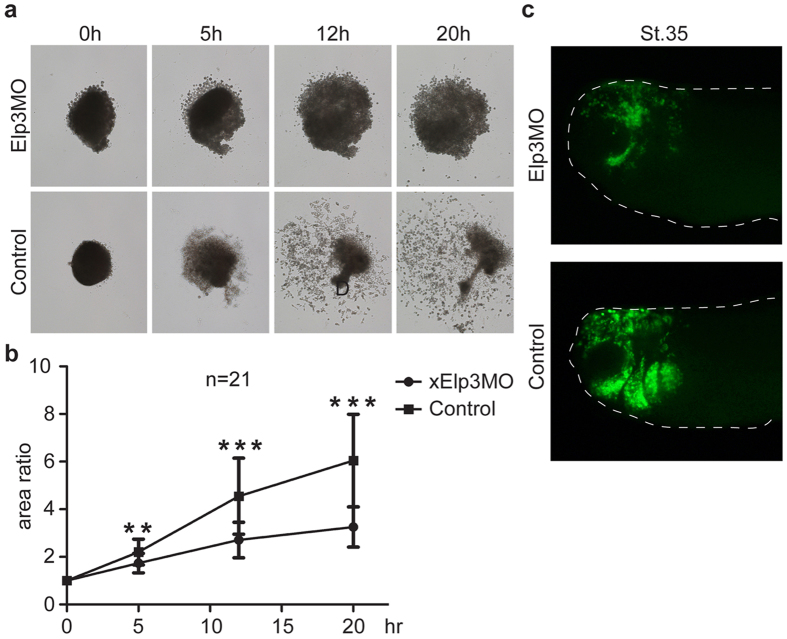

We tested the migratory ability of neural crest cells from the Elp3 morphants in the cranial neural crest (CNC) explant assay. When cultured in vitro, Xenopus CNC cells dissociated and migrated away from the explants on a fibronectin substrate. Indeed, the cells from wild-type neural crest explants migrated from the explants to a considerable distance within a short period (Fig. 3a,b). By contrast, the cells of explants from the Elp3 morphants remained within the explants during the examined period, although they dissociated somewhat (Fig. 3a,b). When GFP-labeled neural crest cells were transplanted into the dorsal region of a host embryo, the grafted cells migrated out efficiently, following prescribed trajectories (Fig. 3c). However, grafted cells from similar regions of the Elp3 morphants mostly stayed where they were transplanted (Fig. 3c), further supporting a role of Elp3 in neural crest migration.

Figure 3. Elp3 is required for cranial neural crest (CNC) migration in explants and transplantation experiments.

(a) CNC explants were dissected from early neurula embryos, plated on FN (10 μg/ml), and imaged at 0, 5, 12, and 20 h. The surface areas of each explant at every image point were measured, and the ratios of the areas to the values at 0 hour are shown by the line plot (b). The data were represented as the means ± standard deviation (SD). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, two-tailed T-test. (c) GFP mRNA (100 pg) was injected into one cell at the 4-cell stage with or without Elp3 morpholino (25 ng). At St.15–16, GFP-labeled CNC explants were dissected and grafted into normal host embryos. The status of the fluorescent neural crest was imaged at the tailbud stage (St.35).

At tadpole stages, the head cartilages in the Elp3 morphants frequently became smaller and malformed while the pigmentation of the embryo was generally normal (data not shown). The modest phenotypic effects on neural crest cell derived tissues suggest the possibility that the effect of Elp3 knockdown might be transient, which delays rather than blocks neural crest migration.

Elp3 stabilizes Snail1

Snail1 is a key inducer of EMT and regulator of neural crest migration. The N-terminal SNAG domain of Snail1 plays an important regulatory role and mediates protein-protein interaction by mimicking the structure of the histone H3 tail24. Because histone H3 is also an Elp3 substrate, we tested whether Elp3 could interact with Snail1 to function in neural crest development.

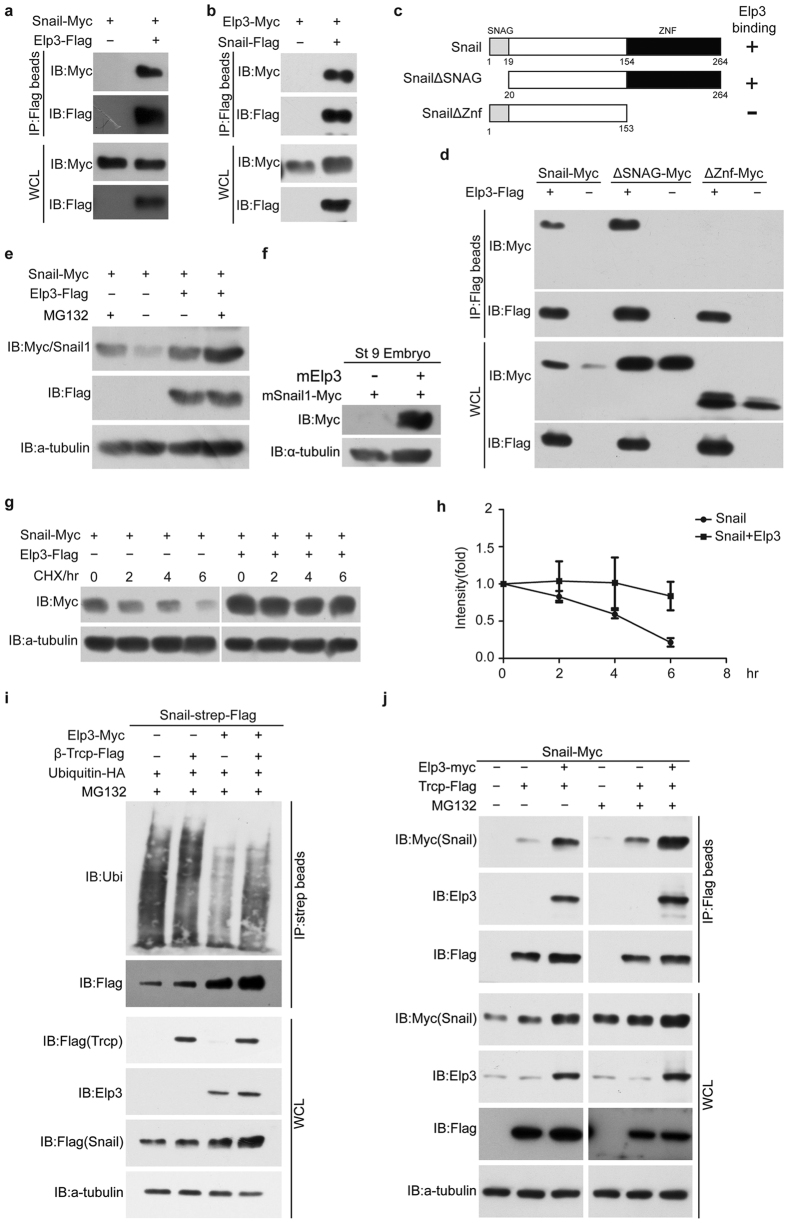

First, we tested whether Elp3 interacts with Snail1. In co-IP assays carried out in mammalian cells, Elp3 could pull down Snail1 and vice versa (Fig. 4a,b). Unexpectedly, the zinc finger domain, not the SNAG domain of Snail1, is indispensable for the interaction (Fig. 4c,d). Snail1 is an unstable protein because it is rapidly polyubiquitinated and degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasomal pathway. Interestingly, co-expression of Elp3 in HEK293 cells or Xenopus embryo dramatically increased the protein level of Snail1 (Fig. 4e,f). We also used a series of cycloheximide-based protein chases to test the protein stability of Snail1 with or without Elp3. Snail1 was clearly stabilized in the presence of Elp3 (Fig. 4g,h). These findings indicated that Elp3 could interact with Snail1 and stabilize it.

Figure 4. Elp3 interacts with and stabilizes Snail1 through inhibiting its ubiquitination.

(a,b) Co-IP assays showing the interaction between Snail1 and Elp3. (c) Schematic representation of the Snail1 deletion constructs. (d) In co-IP experiments, Elp3 pulled down full length and ∆SNAG Snail1 efficiently, but not ∆Znf Snail1. (e) Co-expression of Elp3 stabilizes Snail1 in 293 cells with or without MG132 treatment (10 μM). The cells were lysed 48 hours after transfection and processed for Western blot analysis. MG132 was added 6–8 hours prior to harvesting. (f) Co-expression of mElp3 stabilizes mSnail1 in Xenopus embryo. The injected embryos were lysed at stage 9 and processed for Western blot analysis. (g,h) Elp3 affects the stability of Snail1. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids. At 48 hours post transfection, cycloheximide (CHX) was added to all of the samples, and the cells were then harvested at the timepoints indicated (0 h, 2 h, 4 h, and 6 h). The levels of Snail1 were determined by Western blotting using the anti-Myc antibody (g). In all cases, α-tubulin was used as a loading control. The relative levels of Snail1 were quantified densitometrically and normalized against α-tubulin (h). The data shown in (h) were the average of three independent experiments and represented as the means ± standard error of mean (SEM). (i) Elp3 inhibits Snail1 ubiquitination. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected using the indicated plasmids and were treated for 4–5 hours with MG132 before harvesting. Snail1 proteins were immunoprecipitated using Strep-Tactin beads and were probed with an anti-ubiquitin antibody. (j) Co-IP experiments showing that Elp3 does not interfere with the Snail1/β-Trcp interaction. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids and then were treated for 6–8 hours with or without MG132 before harvesting. The proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag M2 beads and then were detected with the antibody against different tags. WCL, whole cell lysate. IB, immunoblot. IP, immunoprecipitation. CHX, cycloheximide.

Next, we tested whether Elp3 attenuates the ubiquitination of Snail1. In HEK293 cells, exogenously expressed Snail1 was heavily poly-ubiquitinated, while co-expression of Elp3 clearly decreased the level of ubiquitinated Snail1 (Fig. 4i), even in the presence of overexpressed β-Trcp (Fig. 4i), a key E3 ubiquitin ligase that mediates the ubiquitination and degradation of Snail1. We then tested whether Elp3 inhibited the β-Trcp-Snail1 interaction to inhibit Snail1 ubiquitination. Intriguingly, we found that β-Trcp binds Snail1 properly in the presence of Elp3, and the three proteins likely formed a ternary complex (Fig. 4j).

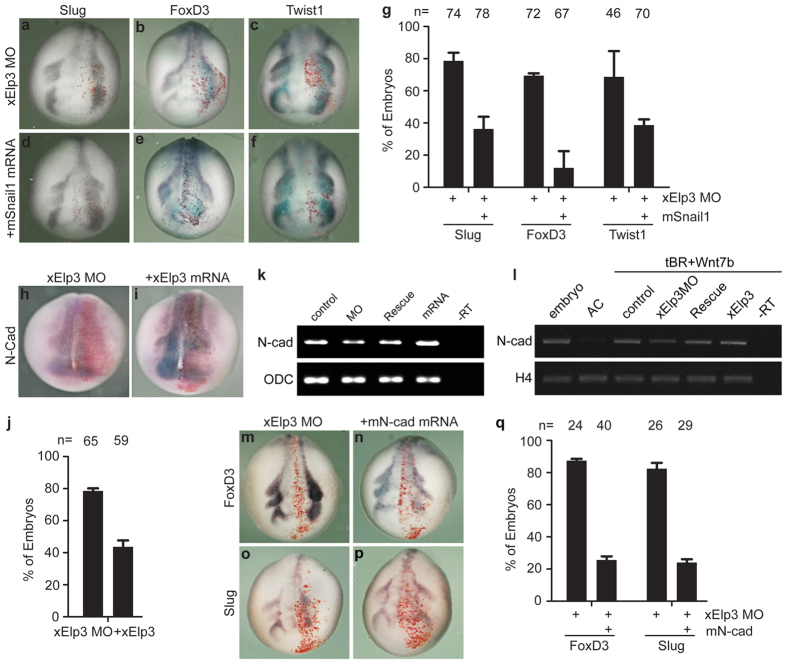

We tested whether overexpression of Snail1 could rescue the migratory ability of neural crest cells in the Elp3 morphants. Indeed, co-injection of mouse Snail1 (mSnail1) mRNA restored the migration of neural crest cells in the Elp3 morphants, as indicated by staining for the neural crest markers Slug, FoxD3 and Twist1 (Fig. 5a–g). Slug (Snail2) is another member of the Snail family transcription factors involved in neural crest induction and migration18,25, which shares similar C2H2 zinc finger motifs with Snail1. We tested whether Elp3 also interacts with Slug. Indeed, mElp3 pulled down efficiently xSlug in a co-IP experiment (Supplementary Fig. S1a), and co-expression of xSlug also rescues the phenotype of Elp3 morphants (Supplementary Fig. S1b,c).

Figure 5. Snail1 or N-cadherin rescues neural crest migration in the Elp3 morphants.

(a–f) Co-injection with mSnail1 mRNA (0.5 ng) rescues the migration of neural crest cells in the Elp3 morphants. (g) Percentages of embryos with reduced migration of neural crest as shown in (a–f). The results are from three independent experiments (error bars represent SDs). (h,i) Knockdown of Elp3 by morpholino down-regulates the N-cadherin level, while co-injection with Elp3 mRNA (0.2 ng) restores its expression. (j) Percentages of embryos with reduced expression of N-cadherin as shown in (h,i). The results are from three independent experiments (error bars represent SDs). (k) The expression levels of N-cadherin in embryos injected with Elp3 morpholino and Elp3 mRNA at St 13. Both cells of the 2-cell stage embryos were injected with Elp3 morpholino (12.5 ng/cell) alone, together with rescue mRNA (0.1 ng/cell), or Elp3 mRNA (0.5 ng/cell) alone. Total RNAs from whole embryos were subjected to RT-PCR analysis for the expression of the indicated genes (cycle numbers: ODC, 24; N-cadherin, 32). (l) Elp3 is required for the expression of N-cadherin in induced animal caps. The embryos were injected animally at 2-cell stage with tBR (0.2 ng/embryo) and Wnt7b (0.5 ng/embryo) to induce neural crest fate. Elp3 morpholino and/or mRNA were co-injected as indicated. Animal caps were dissected at stage 9 and harvested when control embryos reached St 19–21. Total RNAs from the animal caps were subjected to RT-PCR analysis for the expression of the indicated genes (cycle numbers: histone H4, 24; N-cadherin, 31). (m–p) Co-injection with mN-cadherin mRNA (0.1 ng) rescues the migration of neural crest cells. LacZ mRNA was co-injected to trace the injected sides (stained red on the right sides). (q) Percentages of embryos with reduced migration of neural crest as shown in (m–p). The results are from three independent experiments (error bars represent SDs).

Snail1 typically triggers EMT through the transcriptional repression of E-cadherin26 and by activating mesenchymal genes, including N-cadherin27. Interestingly, knockdown of Elp3 reduced N-cadherin expression on the injected sides, and this defect could be rescued by supplementing with xElp3 mRNA (Fig. 5h–j). The result was confirmed by semi-quantitative PCR assay in control and injected whole embryos at stage 13 (Fig. 5k). In animal caps injected with tBR and Wnt7b to induce neural crest fate28, knockdown of Elp3 also reduced the expression of N-cadherin, which was restored when xElp3 mRNA was co-injected (Fig. 5l). In addition, overexpression of mN-cadherin was also sufficient to rescue the migratory defects in the Elp3 morphants (Fig. 5m–q). By contrast, the expression of E-cadherin showed no clear change in the Elp3 morphants (data not shown). Thus, we favor the model that Elp3 binds and stabilizes Snail1, which is required for the transactivation of mesenchymal genes.

Discussion

The Elongator complex was originally identified in yeast as a transcriptional elongation factor functionally coordinating with RNA polymerase II29. The Elongator complex comprises six units, of which Elp3 is the catalytic unit that is indispensable for catalyzing the acetylation reaction. In addition to its role in transcriptional elongation, Elp3 is also involved in cell migration and neurogenesis through the acetylation of α-tubulin5,30. We showed here that Elp3 is expressed in the neural crest territory and is required for neural crest migration in Xenopus embryos. Elp3 interacts with and stabilizes Snail1 through the inhibition of its ubiquitination by β-Trcp. However, in contrast to CSN2, which stabilizes Snail1 through reducing the association between Snail1 and β-Trcp23, Elp3 does not work simply through blocking the β-Trcp-Snail1 interaction because the three proteins were found in one complex. It remains possible that Elp3 interferes with the proper spatial positioning or conformation of Trcp and Snail1 required for the ubiquitination reaction.

Snail1 typically triggers EMT through transcriptional repression. E-cadherin is a characteristic marker that is repressed by Snail1 during the initiation of EMT26. Snail1 represses E-cadherin transcription by recruiting co-repressors to the promoter and inducing transcriptional silencing24,31,32,33. In Xenopus, Snail1 is required for both the specification and migration of neural crest cells and has been suggested to work primarily as a repressor in neural crest induction18,19. However, an increasing body of evidence has indicated that Snail1 can also work as a transcriptional activator during EMT to stimulate mesenchymal genes, including N-cadherin27. In cancer cells, Snail1 knockdown decreases while its induced expression increases N-cadherin expression23,24,27,34,35. However, how exactly Snail1 is involved in N-cadherin regulation remains unknown. In neural crest cells, N-cadherin mediates cell interactions during migration and is required for the contact inhibition of locomotion that is necessary for the collective chemotaxis of neural crest cells36. In the Elp3 morphants, the expression of N-cadherin was significantly reduced, a defect that can be rescued by overexpression of xElp3 (Fig. 5h–k). In addition, the overexpression of mN-cadherin is sufficient to rescue the migratory defects of neural crest cells in the Elp3 morphants (Fig. 5m–q). Our data favor a transactivation function of Snail1 to stimulate N-cadherin expression in neural crest migration. Interestingly, the acetylation of Snail1 by CBP has been shown to render Snail1 an activator by preventing repressor complex formation16. Whether Elp3 works through the acetylation of Snail1 remains to be tested.

Methods

Ethics Statement

The care of Xenopus laevis (Nasco), in vitro fertilization procedure and manipulation of embryos were performed accordingly to standard protocols. All of the animal protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (permit number: SYDW-2006–006).

Embryo microinjection and whole-mount in situ hybridization

In vitro fertilization, embryo culture, whole-mount in situ hybridization, preparation of mRNA, and microinjection were carried out as described previously37. The sequence of the antisense morpholino oligo (MO) for xElp3 is 5′-TTCATGTTGCCCGATGTTCCGCTAG-3′, which targets the 5′ untranslated region plus 5 bases of the coding region and was obtained from Gene Tools. MO and mRNA were injected into the dorsal region of 2- to 4-cell stage embryos. MO was injected at 25 ng/blastomere, and 0.2 ng/blastomere of xElp3 mRNA was coinjected in rescue experiments. For in situ hybridization, the probes of Slug, FoxD3 and Twist1 were used as described previously37.

Plasmid construction

Full-length Xenopus laevis and the mouse Elp3 coding region were obtained by PCR according to sequences in NCBI (accession NM_001095505 and NM_001253812.1) and then were cloned into pCS2+ and pCS2+-C-Flag/pCS2+-N-Myc vectors, respectively. Full-length and truncated mouse Snail1 constructs were obtained by PCR according to sequences in NCBI (accession NM_011427) and were cloned into a pCS2+-N-Myc vector. Snail1 was also subcloned into the pCS2+-C-Flag and pCS2+-C-Strep-Flag vectors for co-IP assays and in vivo ubiquitination assays, respectively. The mouse N-cadherin expression vector was a gift from Dr. Cécile Gauthier-Rouvière (CNRS, France), and the Trcp-Flag expression vector is a gift from Dr. Wei Wu (Tsinghua University, China).

Reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

To analyze the temporal expression of xElp3 during development, RT-PCR was carried out using whole embryos at different developmental stages. The primers used were as follows: xElp3: 5′- TACCTGAGGATTACAGAGAC-3′ and 5′- CTCTCTCCAGTCCCATGTT-3′. The expression levels of N-cadherin in whole embryos or animal caps were also monitored by RT-PCR to reveal the effect of Elp3 using primers as published38. H4 or ODC was used as a loading control38,39.

In vitro cranial neural crest (CNC) migration assay and CNC transplantation

The in vitro CNC migration assay and CNC transplantation experiments were carried out as described previously40,41. CNC explants were dissected from stage 15–16 embryos and were plated onto fibronectin (10 μg/ml in PBS)-coated 96-well plates in Danilchik media (53 mM NaCl, 11.7 mM Na2CO3, 4.25 mM potassium gluconate, 2 mM MgSO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 17.5 mM Bicine, 1 mg/ml BSA; pH 8.3), and images were captured every 4–5 hours for up to 20 hours using an Olympus IX83 inverted microscope. The relative surface areas of the explants were measured using ImageJ.

For grafting experiments, the cranial neural crest explants were dissected from GFP-labeled donor embryos and were inserted isotopically and isochronically into unlabeled host embryos from which the cranial neural crest tissue was removed. The grafted embryos were allowed to heal in 1× MBS media (88 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 2.5 mM NaHCO3, 0.3 mM CaNO3, 0.41 mM CaCl2, 0.82 mM MgSO4, 15 mM HEPES (pH 7.6) with antibiotics) for 30 min-3 hours at room temperature and then were transferred to 0.1× MBS before being imaged at the late tailbud stage42.

Coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) assay and immunoblotting

For Snail1/Elp3 and Snail1/Elp3/Trcp co-IP, HEK293 cells were transfected to 6-well plates with the indicated plasmids. At 48 hours post-transfection (treatment for 6–8 hours with or without MG132 before harvest), the cells were lysed in 700 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA at pH 8.0, and 1% Triton X-100) containing a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche) for 30 min on ice. Following centrifugation at 14000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was incubated with Flag-M2 beads (Sigma) at 4 °C for 4 hours and then washed three times with the lysis buffer at 4 °C for 5 min. The bound proteins were eluted with SDS-loading buffer at 95 °C for 10 min and then were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. The antibodies used were as follows: anti-Flag (M2; Sigma), anti-Myc (Sigma), and anti-Elp3 (Sigma). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or -rabbit IgG (Pierce) was used as the secondary antibody.

In vivo ubiquitination assays

In vivo ubiquitination assays were carried out as described previously43. HEK293 cells were transfected with the HA-ubiquitin construct together with the indicated plasmids. Next, 10 μM of the proteasomal inhibitor MG132 was added 4–5 hours prior to harvesting. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were harvested and lysed in SDS lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 6.8, 1.5% SDS) at 95 °C for 15 min. Following a 10-fold dilution of the lysate with EBC/BSA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 6.8, 180 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40 and 0.5% BSA) plus protease inhibitors (Roche), the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with Strep-Tactin beads (iBA).The bound proteins were eluted using Laemmli sample buffer at 95 °C for 5 min. Western blot analysis was performed using an anti-ubiquitin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The membrane was then stripped and reprobed with the other indicated antibodies.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Yang, X. et al. Elongator Protein 3 (Elp3) stabilizes Snail1 and regulates neural crest migration in Xenopus. Sci. Rep. 6, 26238; doi: 10.1038/srep26238 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the CAS Key Project (KJZD-EW-L08). We thank Drs. C. Gauthier-Rouvière (CNRS, France) and W. Wu (Tsinghua University, China) for plasmids.

Footnotes

Author Contributions X.Y., J.L. and B.M. conceived and designed the study. X.Y. and J.L. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. W.Z. and C.L. conducted part of the experiments. X.Y., J.L. and B.M. wrote the paper. All of the authors discussed and reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Kim J.-H., Lane W. S. & Reinberg D. Human Elongator facilitates RNA polymerase II transcription through chromatin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99, 1241–1246 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittschieben B. Ø. et al. A novel histone acetyltransferase is an integral subunit of elongating RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Molecular cell 4, 123–128 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. et al. The elongator complex interacts with PCNA and modulates transcriptional silencing and sensitivity to DNA damage agents. PLoS Genet 5, e1000684 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miskiewicz K. et al. ELP3 controls active zone morphology by acetylating the ELKS family member Bruchpilot. Neuron 72, 776–788 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creppe C. et al. Elongator controls the migration and differentiation of cortical neurons through acetylation of alpha-tubulin. Cell 136, 551–564 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Close P. et al. Transcription impairment and cell migration defects in elongator-depleted cells: implication for familial dysautonomia. Molecular cell 22, 521–531 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Close P. et al. DERP6 (ELP5) and C3ORF75 (ELP6) regulate tumorigenicity and migration of melanoma cells as subunits of Elongator. Journal of Biological Chemistry 287, 32535–32545 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada Y., Yamagata K., Hong K., Wakayama T. & Zhang Y. A role for the elongator complex in zygotic paternal genome demethylation. Nature 463, 554–558 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin N. M., Creuzet S., Couly G. & Dupin E. Neural crest cell plasticity and its limits. Development 131, 4637–4650 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancur P., Bronner-Fraser M. & Sauka-Spengler T. Assembling Neural Crest Regulatory Circuits into a Gene Regulatory Network. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 26, 581–603 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor R. & Theveneau E. The neural crest. Development 140, 2247–2251 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J. & Thiery J. P. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: insights from development. Development 139, 3471–3486 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theveneau E. & Mayor R. Neural crest delamination and migration: from epithelium-to-mesenchyme transition to collective cell migration. Developmental biology 366, 34–54 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peinado H., Olmeda D. & Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nature reviews. Cancer 7, 415–428 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanisavljevic J., Porta-de-la-Riva M., Batlle R., de Herreros A. G. & Baulida J. The p65 subunit of NF-kappaB and PARP1 assist Snail1 in activating fibronectin transcription. J Cell Sci 124, 4161–4171 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu D. S. et al. Acetylation of snail modulates the cytokinome of cancer cells to enhance the recruitment of macrophages. Cancer cell 26, 534–548 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Herreros A. G., Peiro S., Nassour M. & Savagner P. Snail family regulation and epithelial mesenchymal transitions in breast cancer progression. Journal of mammary gland biology and neoplasia 15, 135–147 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aybar M. J. Snail precedes Slug in the genetic cascade required for the specification and migration of the Xenopus neural crest. Development 130, 483–494 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBonne C. & Bronner-Fraser M. Snail-related transcriptional repressors are required in Xenopus for both the induction of the neural crest and its subsequent migration. Dev Biol 221, 195–205 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrallo-Gimeno A. & Nieto M. A. The Snail genes as inducers of cell movement and survival: implications in development and cancer. Development 132, 3151–3161 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B. P. et al. Dual regulation of Snail by GSK-3β-mediated phosphorylation in control of epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Nature cell biology 6, 931–940 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz V. M., Vinas-Castells R. & Garcia de Herreros A. Regulation of the protein stability of EMT transcription factors. Cell Adh Migr 8, 418–428 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. et al. Stabilization of snail by NF-κB is required for inflammation-induced cell migration and invasion. Cancer cell 15, 416–428 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. et al. The SNAG domain of Snail1 functions as a molecular hook for recruiting lysine-specific demethylase 1. The EMBO journal 29, 1803–1816 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carl T., Dufton C., Hanken J. & Klymkowsky M. Inhibition of Neural Crest Migration in Xenopus Using Antisense Slug RNA. Developmental Biology 213, 101–115 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A. et al. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial–mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nature cell biology 2, 76–83 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javaid S. et al. Dynamic chromatin modification sustains epithelial-mesenchymal transition following inducible expression of Snail-1. Cell reports 5, 1679–1689 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. & Hemmatibrivanlou A. Neural Crest Induction by Xwnt7B in Xenopus. Developmental Biology 194, 129–134 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otero G. et al. Elongator, a multisubunit component of a novel RNA polymerase II holoenzyme for transcriptional elongation. Molecular cell 3, 109–118 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solinger J. A. et al. The Caenorhabditis elegans Elongator complex regulates neuronal alpha-tubulin acetylation. PLoS Genet 6, e1000820 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Z. et al. The LIM protein AJUBA recruits protein arginine methyltransferase 5 to mediate SNAIL-dependent transcriptional repression. Molecular and cellular biology 28, 3198–3207 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peinado H., Ballestar E., Esteller M. & Cano A. Snail mediates E-cadherin repression by the recruitment of the Sin3A/histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1)/HDAC2 complex. Molecular and cellular biology 24, 306–319 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herranz N. et al. Polycomb complex 2 is required for E-cadherin repression by the Snail1 transcription factor. Molecular and cellular biology 28, 4772–4781 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evdokimova V. et al. Translational activation of snail1 and other developmentally regulated transcription factors by YB-1 promotes an epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer cell 15, 402–415 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshiere A. et al. Unbalanced expression of CK2 kinase subunits is sufficient to drive epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by Snail1 induction. Oncogene 32, 1373–1383 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theveneau E. et al. Collective chemotaxis requires contact-dependent cell polarity. Dev Cell 19, 39–53 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Shi Y., Sun J., Zhang Y. & Mao B. Xenopus reduced folate carrier regulates neural crest development epigenetically. PloS one 6, e27198 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandadasa S., Tao Q., Menon N. R., Heasman J. & Wylie C. N- and E-cadherins in Xenopus are specifically required in the neural and non-neural ectoderm, respectively, for F-actin assembly and morphogenetic movements. Development 136, 1327–1338 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. et al. Xenopus nkx6.3 is a neural plate border specifier required for neural crest development. Plos one 9, e115165 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Y. S., Luo T., Xu Y. & Sargent T. D. Myosin-X is required for cranial neural crest cell migration in Xenopus laevis. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists 238, 2522–2529 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie S., Kee Y. & Bronner-Fraser M. Myosin-X is critical for migratory ability of Xenopus cranial neural crest cells. Developmental biology 335, 132–142 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchers A., Epperlein H.-H. & Wedlich D. An assay system to study migratory behavior of cranial neural crest cells in Xenopus. Development genes and evolution 210, 217–222 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma P. et al. The ubiquitin ligase RNF220 enhances canonical Wnt signaling through USP7-mediated deubiquitination of beta-catenin. Molecular and cellular biology 34, 4355–4366 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.