Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine clinicopathologic variables associated with survival among women with low-grade (grade 1) serous ovarian carcinoma enrolled in a phase III study.

METHODS

This was an ancillary data analysis of Gynecologic Oncology Group protocol 182, a phase III study of women with stage III–IV epithelial ovarian carcinoma treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel compared with triplet or sequential doublet regimens. Women with grade 1 serous carcinoma (a surrogate for low-grade serous disease) were included in the analysis.

RESULTS

Among the 3,686 enrolled participants, 189 had grade 1 disease. The median age was 56.5 years and 87.3% had stage III disease. The median follow-up time was 47.1 months. Stratification according to residual disease after primary surgery was microscopic residual in 24.9%, 0.1–1.0 cm of residual in 51.3%, and more than 1.0 cm of residual in 23.8%. On multivariate analysis, only residual disease status (P=.006) was significantly associated with survival. Patients with microscopic residual had a significantly longer median progression-free (33.2 months) and overall survival (96.9 months) compared with those with residual 0.1–1.0 cm (14.7 months and 44.5 months, respectively) and more than 1.0 cm of residual disease (14.1 months and 42.0 months, respectively; progression-free and overall survival, P<.001). After adjustment for other variables, patients with low-grade serous carcinoma with measurable residual disease had a similar adjusted hazard ratio for death (2.12; P=.002) as their high-grade serous carcinoma counterparts with measurable disease (2.31; P<.001).

CONCLUSIONS

Surgical cytoreduction to microscopic residual was associated with improved progression-free and overall survival in women with advanced-stage low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

Ovarian carcinoma is the leading cause of death from gynecologic cancers in the United States.1 Several studies demonstrate that histologic grade is one of the most important prognostic factors in epithelial ovarian cancer; however, no universal grading schema exists for ovarian serous carcinoma, the most common subtype. Recently, a two-tiered system (low-grade compared with high-grade) was proposed by Malpica et al2 and has received increasing acceptance. This system is primarily based on assessment of nuclear atypia and mitotic rate. A growing body of research demonstrates several important differences in the molecular and clinical characteristics of low-grade compared with high-grade serous carcinoma, but similarities between low-grade and serous tumors of low malignant potential.3–18 There is good correlation between the two-tiered system and the established International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics and Shimizu-Silverberg systems.3,4

Low-grade serous carcinoma represents approximately 10% of all serous ovarian carcinomas. Retrospective studies propose that low-grade serous ovarian tumors are diagnosed in women at a younger age and they experience a longer overall survival than those with high-grade disease. Despite these data, several reports suggest that women with low-grade disease exhibit poor response rates to conventional chemotherapy17–19 and remain at high risk for recurrence and cancer-related death, especially in the setting of advanced-stage disease.

We performed an ancillary analysis of Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) protocol 182,20 a cooperative group randomized trial, to determine the clinicopathologic variables associated with recurrence and survival among women with low-grade (grade 1) serous ovarian carcinoma enrolled in this study and, secondarily, to compare the outcomes of those with low-grade and high-grade disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was an ancillary data analysis of GOG-182, a multicenter phase III study of stage III–IV primary epithelial ovarian carcinoma patients with optimal (maximal diameter of residual disease less than 1.0 cm) and suboptimal (more than 1.0 cm) residual disease treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel alone or in combination with triplet or sequential doublet regimens.20 Institutional Review Board approval at all participating GOG-182 study sites was previously obtained. The sample was limited to all eligible patients from that clinical trial, from which we examined patients with grade 1 (n=189) and higher-grade (n=1,763) serous ovarian carcinoma. All women received the backbone of intravenous carboplatin and paclitaxel with the addition of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, topotecan, or gemcitabine. For the current analysis, women with grade 1 serous carcinoma (used as a surrogate for low-grade serous carcinoma) diagnosed were the primary focus. However, those with grade 2 or 3 serous tumors also were studied in select comparative demographic and survival analyses. Central pathology review of all tumors studied in the current analysis had been performed by the GOG Pathology Committee (of note, this committee reviewed the pathology of all study participants enrolled from the United States, which represented approximately 85% of all women). Demographic, clinical, and surgical factors were evaluated for their effect on progression-free survival and overall survival outcomes.

Although the standard definition of optimal cytoreduction is considered as residual disease no larger than 1 cm in diameter after primary surgery, recent studies have focused on the survival benefit associated with “no gross” or microscopic residual disease achieved from maximal surgical resection.21 These studies demonstrate that in women with high-grade epithelial ovarian carcinoma and microscopic residual disease after primary cytoreduction, significantly longer median overall survival is observed than in those with any residual disease remaining, advocating for more a more contemporary definition of residual disease status, ie, more quantitative. Therefore, in the current study, residual disease status after primary cytoreductive surgery was defined as microscopic residual (no gross residual disease), 0.1–1.0 cm maximal diameter of residual disease, or more than 1.0 cm maximal diameter of residual disease. Progression-free and overall survival functions were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier procedure.22 The log-rank test was used to make comparisons based on tumor grade. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to confirm the independent prognostic value of various clinical variables.22,23 Covariates were included for adjustment based on the prognostic variables identified by previous GOG studies. All variables considered as prognostic factors were included in a Cox proportional hazards regression model. Because of small counts in some of its categories, race was collapsed into the categories “white” (n=172), “black” (n=9), and “other” (n=8).

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test,23 Kruskal–Wallis test, and Pearson χ2 test were used to assess associations between stratifying variables and patient clinico-demographic characteristics. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with the significance level set at α=0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the R programming language and environment.24

RESULTS

Among the 3,686 eligible women enrolled in GOG-182, 189 had grade 1 serous carcinoma of the ovary. The demographic and prognostic characteristics of the low-grade cohort are described in Table 1. The mean study participant age was 56.6 years, and the majority of participants were white. Forty-nine percent had a normal, asymptomatic performance status. Most women (87%) had stage III disease. Sixty-three percent presented with ascites and had a median pretreatment CA 125 level of 119 units/mL. With regard to tumor residual after cytoreductive surgery, 24.9% were left with microscopic residual, 51.3% had residual disease measuring 0.1–1.0 cm, and 23.8% were left with more than 1.0 cm residual disease. When compared with the high-grade serous carcinoma cohort, those with grade 1 disease were younger (P<.001), had higher body mass indexes (calculated as weight (kg)/[height (m)]2, P=.007), had lower CA 125 levels (P<.001), and were less likely to have ascites (P<.001; Table 1). However, residual disease status after primary surgery was not different between the grade 1 and the higher-grade serous cohorts, with more than 75% undergoing cytoreduction to 0–1.0 cm diameter of gross residual disease and no more than 25% undergoing cytoreduction to microscopic residual in both groups.

Table 1.

Low-Grade* Compared With High-Grade Serous Carcinoma Patient Characteristics

| Variable | n | Low-Grade Serous Carcinoma (n = 189) |

High-Grade Serous Carcinoma (n = 1,763) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 1,952 | 56.5 (46.6–64.3) | 59.3 (51.6–67.3) | <.001† |

| Race | 1,952 | .731‡ | ||

| White | 172 (91.0) | 1,596 (90.5) | ||

| Black | 9 (4.8) | 72 (4.1) | ||

| Other | 8 (4.2) | 95 (5.4) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1,871 | 26.6 (23.4–30.3) | 25.2 (22.2–29.6) | .007† |

| Performance status | 1,952 | .444‡ | ||

| Normal, asymptomatic | 93 (49.2) | 860 (48.8) | ||

| Symptomatic, ambulatory | 87 (46.0) | 776 (44.0) | ||

| Symptomatic, in bed | 9 (4.8) | 127 (7.2) | ||

| Top-level FIGO stage | 1,952 | .284‡ | ||

| III | 165 (87.3) | 1,487 (84.3) | ||

| IV | 24 (12.7) | 276 (15.7) | ||

| Tumor residual | 1,952 | .106‡ | ||

| Microscopic | 47 (24.9) | 258 (20.3) | ||

| 0.1–1 cm | 97 (51.3) | 866 (47.5) | ||

| More than 1 cm | 45 (23.8) | 539 (28.5) | ||

| CA 125 (units/mL) | 1,882 | 119.1 (51.8–323.9) | 246.7 (101.8–719.8) | <.001† |

| Ascites | 1,905 | <.001‡ | ||

| No | 69 (36.9) | 418 (24.3) | ||

| Yes | 118 (63.1) | 1,300 (75.7) |

BMI, body mass index; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Data are median (range) or n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Grade 1 disease is a surrogate for low-grade serous carcinoma.

Wilcoxon test.

Pearson χ2 test.

Eighty-six percent of those with grade 1 serous carcinoma had nonmeasurable disease on imaging at completion of primary therapy, and this was not significantly different for those with high-grade disease (83.1%; P=.273). After a median follow-up time of 47.1 months (interquartile range 27.4–92.0 months), 86.8% of women with low-grade disease experienced a recurrence; 66.7% died of disease. There was no difference in survival of the patients with grade 1 serous carcinoma when triplet or sequential doublet therapy was added to platinum and taxane therapy, consistent with the previously published results for the overall GOG-182 study population. The demographic and prognostic factors of the patients with grade 1 serous carcinoma were well-balanced among the five chemotherapy treatment arms and cytoreductive surgery cohorts. Univariate analysis, which included age, race, GOG performance status, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage, residual disease status, presence of ascites, and treatment arm, demonstrated that residual disease (P<.001) and ascites (P=.032) were associated with poor progression-free survival. Further, residual disease (P<.001) was significantly associated with overall survival.

Table 2 demonstrates recurrence rates by residual disease status for the grade 1 serous cohort. In those with measurable residual disease after primary cytoreductive surgery, 90.8% experienced disease recurrence compared with 74.5% in those with no measurable disease (P=.004). All variables considered as prognostic factors based on univariate analysis were included in a Cox proportional hazards regression model (Table 3). When normal, asymptomatic patients with grade 1 serous carcinoma were used as the referent, the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for death in patients with symptomatic ambulatory performance status was 1.47 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.00–2.17; P=.048). The overall test for residual disease, however, was strongly significant in both the progression-free survival (P<.001) and overall survival models (P=.006). When patients with microscopic residual disease were used as the referent, the adjusted HR for progression in those with 0.1–1 cm of residual disease was 3.13 (95% CI 1.96–4.98; P<.001); the adjusted HR for progression in those with more than 1 cm of residual disease was 3.31 (95% CI 1.87–5.85; P<.001). Likewise, the adjusted HR for death in patients with 0.1–1 cm of disease was 2.31 (95% CI 1.37–3.90; P=.002), and the adjusted HR for death in those with more than 1.0 cm of residual disease was 2.45 (95% CI 1.30–4.64; P=.006).

Table 2.

Low-Grade Serous Carcinoma Recurrence Rates by Disease Residual

| Nonmeasurable Disease (n=47) |

Measurable Disease (n= 142) |

P* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrence | .004 | ||

| No | 12 (25.5) | 13 (9.2) | |

| Yes | 35 (74.5) | 129 (90.8) |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Pearson χ2 test.

Table 3.

Multivariable Analysis of Progression-Free and Overall Survival of Low-Grade* Serous Carcinoma Population by Prognostic Factors

| Prognostic Factor | n | Progression-Free Survival Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

P† | Overall Survival Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

P† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 189 | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | .769 | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | .838 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 172 | Referent | .069‡ | Referent | .477‡ |

| Black | 9 | 0.42(0.19–0.92) | .031 | 0.59 (0.21–1.66) | .317 |

| Other | 8 | 0.65 (0.28–1.48) | .304 | 1.32 (0.54–3.24) | .538 |

| Performance status | |||||

| Normal, asymptomatic | 93 | Referent | .290‡ | Referent | .139‡ |

| Symptomatic, ambulatory | 87 | 1.26 (0.90–1.78) | .181 | 1.47(1.00–2.17) | .048 |

| Symptomatic, in bed | 9 | 0.84 (0.4–1.78) | .648 | 1.16 (0.53–2.53) | .719 |

| Top-level FIGO stage | |||||

| III | 165 | Referent | .282‡ | Referent | .890‡ |

| IV | 24 | 1.30 (0.81–2.08) | .282 | 1.04 (0.61–1.76) | .890 |

| CA 125 (units/mL) | 184 | 1.11(0.97–1.27) | .137 | 1.13 (0.98–1.30) | .094 |

| Ascites | |||||

| No | 69 | Referent | .344‡ | Referent | .465‡ |

| Yes | 118 | 1.21 (0.81–1.80) | .344 | 1.18 (0.76–1.82) | .465 |

| Tumor residual | |||||

| Microscopic | 47 | Referent | <.001‡ | Referent | .006‡ |

| Optimal (0.1–1 cm) | 97 | 3.13 (1.96–4.98) | <.001 | 2.31 (1.37–3.90) | .002 |

| Suboptimal (more than 1 cm) | 45 | 3.31 (1.87–5.85) | <.001 | 2.45 (1.30–4.64) | .006 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Grade 1 disease is a surrogate for low-grade serous carcinoma.

Wald test.

Overall analysis of variance type test.

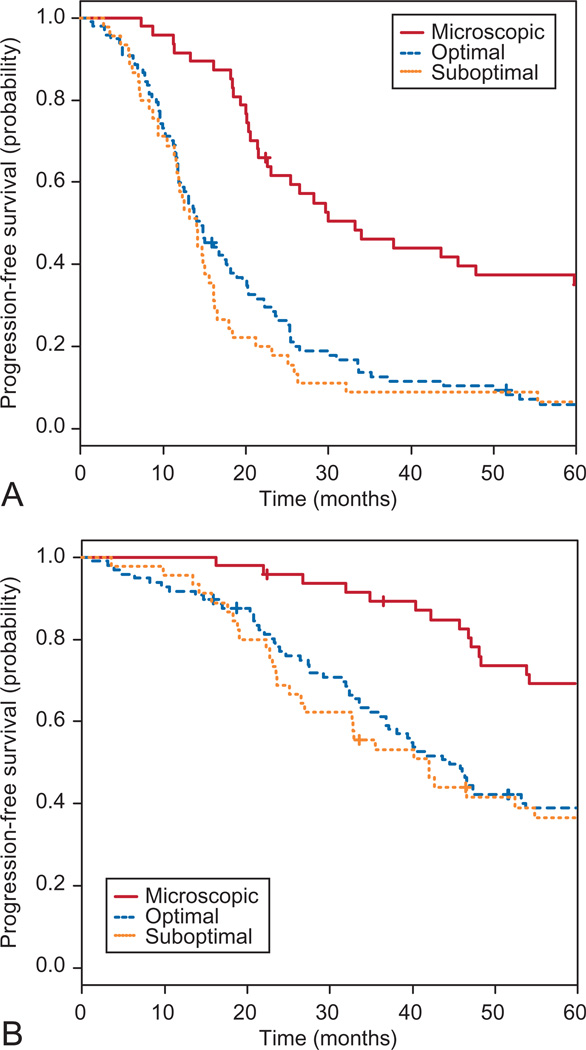

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the study participants with grade 1 serous carcinoma are shown in Figure 1A and B. The median progression-free survival was 16.72 months (95% CI 14.82–20.11), and the median overall survival was 48.33 months (95% CI 45.70–66.50). When stratified by extent of residual disease, women who underwent cytoreductive surgery of microscopic residual had a significantly improved median progression-free survival (33.2 months) compared with those with residual 0.1–1.0 cm (14.65 months) or women left with more than 1.0 cm of disease (14.1 months; P<.001). Similarly, the cohort who underwent cytoreductive surgery that achieved microscopic residual experienced a significantly longer median overall survival at 96.9 months compared with 45 months for those with 0.1–1.0 cm of residual disease and 42 months for those with more than 1.0 cm of residual disease (P<.001; Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

A. Progression-free survival of grade 1 patients stratified by extent of residual disease (log-rank test, P<.001). Median progression-free survival for the microscopic group was 33.2 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 23.1–72.6), 14.7 months (95% CI 12.1–18.2) for the optimal (0.1–1.0 cm) group, and 14.1 months (95% CI 11.6–16.1) for the suboptimal (more than 1 cm) group. B. Overall survival of patients with low-grade serous carcinoma stratified by extent of residual disease (log-rank test, P<.001). Median overall survival for the microscopic group was 96.9 months (95% CI 76.2–not applicable), 44.5 months (95% CI 37.1–60.9) for the optimal group, and 42.0 months (95% CI 27.0–66.5) for the suboptimal group. The crosses in each panel represent censored data.

Fader. Low-Grade Serous Carcinoma and Survival. Obstet Gynecol 2013.

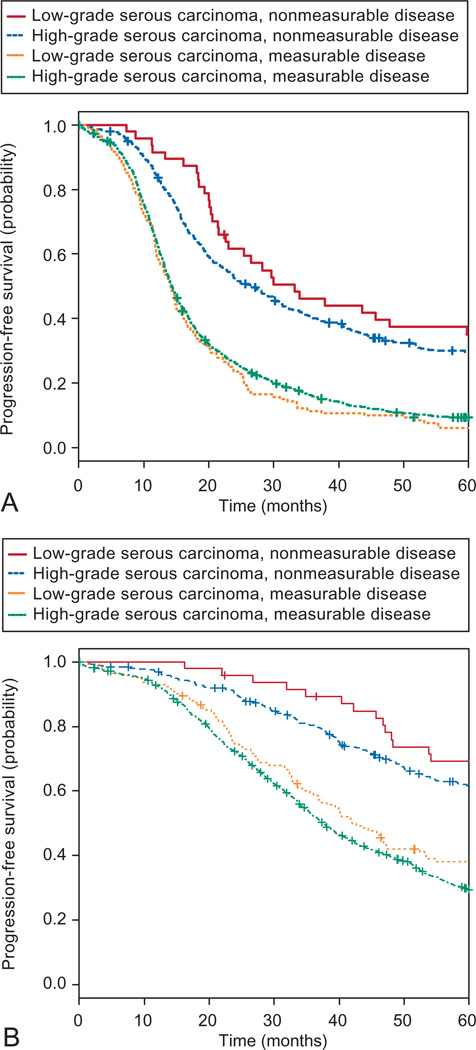

Fig. 2.

A. Progression-free survival of Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) 182 protocol patients stratified by tumor grade and residual disease (log-rank test, P<.001). Progression-free survival for the low-grade serous carcinoma nonmeasurable disease group was 33.2 months (95% CI 23.1–72.6), 26.8 months (95% CI 22.8–31.3) for the high-grade serous carcinoma nonmeasurable disease group, 14.1 months (95% CI 12.5–16.1) for the low-grade serous carcinoma measurable disease group, and 14.4 months (95% CI 13.9–14.9) for the high-grade serous carcinoma measurable disease group. B. Overall survival of GOG-182 patients stratified by tumor grade and residual disease (log-rank test, P<.001). Median overall survival for the low-grade serous carcinoma nonmeasurable disease group was 96.9 months (95% CI 76.2–not applicable), 77.1 months (95% CI 67.5–88.8) for the high-grade serous carcinoma nonmeasurable disease group, 42.0 months (95% CI 36.8–53.2) for the low-grade serous carcinoma measurable disease group, and 37.7 months (95% CI 35.9–39.4) for the high-grade serous carcinoma measurable disease group. The crosses in each panel represent censored data.

Fader. Low-Grade Serous Carcinoma and Survival. Obstet Gynecol 2013.

Survival of the grade 1 cohort was then compared with that of the higher-grade serous carcinoma study cohort. Table 4 demonstrates that when stratified by extent of residual disease, those with grade 1 and no gross residual disease after surgery experienced the longest median progression-free survival at 33.2 months, followed by those with high-grade disease and no gross residual disease with a median progression-free survival of 26.8 months. In contrast, those with grade 1 and higher-grade serous carcinoma with any residual measurable disease after surgery experienced almost identical and shorter progression-free survival outcomes (14.11 months and 14.39 months, respectively; P<.001). Similarly, those with grade 1 and no gross residual disease after surgery experienced the longest median overall survival at 96.89 months, followed by those with high-grade disease and no gross residual disease with a median overall survival of 77.07 months, whereas those with low-grade and high-grade serous carcinoma with any residual measurable disease after surgery experienced much shorter median overall survival rates (42.02 months and 37.68 months, respectively; P<.001). Kaplan–Meier survival curves for those with low-grade and high-grade serous carcinoma are shown in Figure 2A and B. Finally, after controlling for other variables, when comparing the risks of progression and death for women with low-grade compared with high-grade serous carcinoma, those with low-grade tumors and measurable residual disease after primary cytoreductive surgery had adjusted HRs for disease progression (HR 2.28, P<.001) and death (HR 2.12, P=.002) similar to their high-grade counterparts with measurable disease.

Table 4.

Progression-Free Survival and Overall Survival by Tumor Grade and Residual Disease Status

| Strata | n | Progression-Free Survival in Months (P<.001)* |

Progression-Free Survival Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

P† | Overall Survival in Months (P<.001)* |

Overall Survival, Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

P† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-grade serous carcinoma, nonmeasurable |

47 | 33.22 (23.10–72.61) | Referent | — | 96.89 (76.82–—) | Referent | — |

| High-grade serous carcinoma, nonmeasurable |

358 | 26.84 (22.84–31.28) | 1.06 (0.74–1.52) | .742 | 77.07 (67.48– 88.84) |

1.32 (0.84–2.05) | .224 |

| Low-grade serous carcinoma, measurable |

142 | 14.11 (12.52–16.10) | 2.28 (1.56–3.33) | <.001 | 42.02 (36.83– 53.19) |

2.12 (1.33–3.38) | .002 |

| High-grade serous carcinoma, measurable |

1,405 | 14.39 (13.86–14.88) | 1.75(1.24–2.46) | .002 | 37.68 (35.84– 39.39) |

2.31 (1.50–3.55) | <.001 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Data are median (range) unless otherwise specified.

Log-rank test for comparing survival distributions.

Wald test for individual predictors in the Cox model

DISCUSSION

Approximately 75% of women with newly diagnosed invasive epithelial ovarian cancer present with stage III or IV disease. Studies demonstrate that survival rates improve accordingly when the primary cytoreductive surgical paradigm is aggressive and incorporates radical techniques aimed at achieving microscopic residual disease.25 For purposes of uniformity, the GOG has defined optimal cytoreduction as residual implants smaller than 1 cm in diameter, although increasing evidence suggests that those women who undergo a primary cytoreductive procedure for microscopic or “no gross” residual experience the best survival outcomes.25 Despite this, it remains controversial whether the better outcome is attributable to the technical proficiency of the surgeon or the intrinsic biology of the cancer that may allow for easier removal of the tumors. Notably, in the current ancillary analysis of GOG-182, although the women in the low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma cohort were younger at diagnosis, had a lower initial serum CA 125, and had a lower likelihood of tumors that produced ascites than the high-grade serous cohort (P<.001 for all), the frequency of achieving no gross residual disease at primary cytoreductive surgery was essentially similar between the low-grade and high-grade groups (~25%). This speaks to factors other than tumor grade and biology that may contribute to the ability to achieve optimal resection.

Although there is considerable data from phase III epithelial ovarian carcinoma trials regarding the optimal treatment of those with high-grade serous carcinoma,20 less is known about the best treatment strategies for those with grade 1 (low-grade serous) disease. In the current clinicopathologic analysis of GOG-182, only residual disease status after primary surgery was significantly associated with survival. When stratified by extent of residual tumor, patients with microscopic residual had a significantly longer median overall survival compared with those with any disease residual. Further, the HRs for progression and death for patients with residual of 0.1–1.0 cm and residual disease more than 1.0 cm were virtually identical, suggesting that patients with any residual disease did not have a durable recurrence-free interval or a robust response to adjuvant chemotherapy.

In fact, the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the low-grade (grade 1) serous cohort in the current study illustrated a much stronger effect of residual disease than observed with the larger previously published GOG-182 study cohort.20 In other words, the survival differences in those who underwent surgery for no gross residual compared with those who were left with macroscopic disease were more striking in the low-grade cohort than in the high-grade serous cohort (Fig. 2A and B). Although it is known that high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma is moderately sensitive to platinum-based and taxane-based chemotherapy,20 the same does not appear to be true of low-grade serous carcinoma, which has a relatively low mitotic index and is considerably more chemoresistant. Consequently, it could be hypothesized that chemotherapy is relatively inactive in low-grade serous carcinoma; therefore, the potential benefit associated with maximal cytoreductive surgery may be more pronounced in this cohort than in those with high-grade disease. Our data suggest that it is of critical importance to consider an aggressive primary surgical cytoreductive effort in women with primary ovarian carcinoma, irrespective of disease grade.

There is clear biologic and pathologic evidence indicating that low-grade compared with high-grade serous tumors develop through different pathways.24,26–29 Whereas the high-grade tumors exhibit a prevalence of p53 mutations and grow rapidly, the low-grade tumors are notable for mutations in the RAS-RAF-MAPK pathways and for their indolent course. These clinicopathologic factors may account for the fact that conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy agents, including the platinum and taxane drugs, have not exhibited exceptional activity against low-grade serous carcinoma tumors.19,28 The preponderance of RAS-RAF-MAPK signaling in low-grade serous carcinoma represents an appealing therapeutic target for patients. A recent, open-label, phase II GOG study of selumetinib, a MEK 1 and MEK 2 inhibitor, was quite tolerable and demonstrated excellent activity in recurrent low-grade serous carcinoma.29 The emergence of specific targeted therapies with beneficial effects in this cohort of patients further highlights the importance of identifying those with low-grade disease by the two-tiered criteria.

An ancillary analysis of GOG protocol 158 demonstrated that patients with grade 1 serous carcinoma (a reproducible surrogate of low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma) had significantly improved survival outcomes compared with those with grade 2–3 disease.4 However, GOG-158 included only 21 women with low-grade disease, all of whom had undergone an optimal cytoreductive surgery. In contrast, the current GOG-182 ancillary study contains a substantially larger subset of patients with stage III–IV, low-grade serous carcinoma who underwent both optimal and suboptimal cytoreduction. When including “all-comers” with advanced-stage, low-grade disease, our study suggests that the survival outcomes may not be as robust as previously believed, especially when residual disease remains after primary cytoreductive surgery.

Study weaknesses include the ad hoc analysis with its intrinsic limitations and the fact that study participants received a heterogeneous array of adjuvant therapies. Study strengths include that data were prospectively collected from a phase III GOG study, tumor specimens had undergone central pathology review by gynecologic pathologists, and the large sample size of women with low-grade serous carcinoma.

Our analysis suggests that women with advanced-stage, low-grade (grade 1) serous carcinoma have a high risk of recurrence and cancer-related death. In those who are left with any gross residual disease after primary cytoreductive surgery, the risk for death is almost identical to that of women with high-grade serous carcinoma. Cytoreductive surgery with the goal of microscopic residual disease appears to improve progression-free and overall survival. Given that low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma is not exceptionally chemosensitive, it is particularly compelling to consider an attempt at maximal primary cytoreductive surgery in this population and to continue to investigate potentially active cytotoxic and targeted agents for the treatment of this disease.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Cancer Institute grants to the Gynecologic Oncology Group Administrative Office (CA 27469) and the Gynecologic Oncology Group Statistical Office (CA 37517).

Footnotes

Presented at a plenary session at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer, March 24, 2012 Austin, Texas.

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Winter WE, 3rd, Maxwell GL, Tian C, Carlson JW, Ozols RF, Rose PG, et al. Prognostic factors for stage III epithelial ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3621–3627. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malpica A, Deavers MT, Lu K, Bodurka DC, Atkinson EN, Gershenson DM, et al. Grading ovarian serous carcinoma using a two-tier system. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:496–504. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200404000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malpica A, Deavers MT, Tornos C, Kurman RJ, Soslow R, Seidman JD, et al. Interobserver and intraobserver variability of a two-tier system for grading ovarian serous carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1168–1174. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31803199b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodurka DC, Deavers MT, Tian C, Sun CC, Malpica A, Coleman RL. Reclassification of serous ovarian carcinoma by a 2-tier system: a gynecologic oncology group study. Cancer. 2012;118:3087–3094. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gershenson DM, Sun CC, Lu KH, Coleman RL, Ak Sood, Malpica A, et al. Clinical behavior of stage II-IV low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;2:361–368. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000227787.24587.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozols RF, Bundy BN, Greer BE, Fowler JM, Clarke-Pearson D, Burger RA, et al. Phase III trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel compared with cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with optimally resected stage III ovarian cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;17:3194–3200. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fink A. How to manage, analyze, and interpret survey data. 2nd. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baak JP, Delemarre JF, Langley FA, Talerman A. Grading ovarian tumors. Evaluation of decision making by different pathologists. Anal Quant Histol. 1986;8:349–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stalsberg H, Abeler V, Blom GP, Bostad L, Skarland E, Westqaard G. Observer variation in histologic classification of malignant and borderline ovarian tumors. Hum Pathol. 1988;19:1030–1035. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(88)80082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertelsen K, Holund B, Anderson E. Reproducibility and prognostic value of histologic type and grade in early epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1993;3:72–79. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.1993.03020072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimizu Y, Kamoi S, Amada S, Akiyama F, Silverberg SG. Toward the development of a universal grading system for ovarian epithelial carcinoma: testing of a proposed system in a series of 461 patients with uniform treatment and follow-up. Cancer. 1998;82:893–901. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980301)82:5<893::aid-cncr14>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishioka S, Sagae S, Terasawa K, Sugimura M, Nishioka Y, Tsukada K, et al. Comparison of the usefulness between a new universal grading system for epithelial ovarian cancer and the FIGO grading system. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:447–452. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seidman JD, Horkayne-Szakaly I, Cosin JA, Ryu HS, Haiba M, Boice CR, et al. Testing of two binary grading systems for FIGO stage III serous carcinoma of the ovary and peritoneum. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;103:703–708. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonome T, Lee JY, Park DC, Radonovich M, Pise-Masison C, Brady J, et al. Expression profiling of serous low malignant potential, low-grade, and high-grade tumors of the ovary. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10602–10612. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jazaeri AA, Lu K, Schmandt R, Harris CP, Rao PH, Sotiriou C, et al. Molecular determinants of tumor differentiation in papillary serous ovarian carcinoma. Mol Carcinog. 2003;36:53–59. doi: 10.1002/mc.10098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meinhold-Heerlein I, Bauerschlag D, Hilpert F, Dimitrov P, Sapinoso LM, Orlowska-Volk M, et al. Molecular and prognostic distinction between serous ovarian carcinomas of varying grade and malignant potential. Oncogene. 2005;24:1053–1065. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sieben NL, Macropoulos P, Roemen GM, Kolkman-Uljee SM, Jan Fleuren G, Houmadi R, et al. In ovarian neoplasms, BRAF, but not KRAS, mutations and restricted to low-grade serous tumours. J Pathol. 2004;202:336–340. doi: 10.1002/path.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmeler KM, Gershenson DM. Low-grade serous ovarian cancer: a unique disease. Curr Oncol Rep. 2008;10:519–523. doi: 10.1007/s11912-008-0078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singer G, Oldt R, 3rd, Cohen Y, Wang BG, Sidransky D, Kurman RJ, et al. Mutations in BRAF and KRAS characterize the development of low-grade ovarian serous carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:484–486. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.6.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bookman MA, Brady MF, McGuire WP, Harper PG, Alberts DS, Friedlander M, et al. Evaluation of new platinum-based treatment regimens in advanced-stage ovarian cancer: a phase III trial of the Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1419–1425. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang SJ, Bristow RE, Ryu HS. Impact of complete cytoreduction leaving no gross residual disease associated with radical cytoreductive surgical procedures on survival in advanced ovarian cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012 Jul 6; doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2446-8. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitehead J. Sample size calculations for ordered categorical data. Stat Med. 1993;12:2257–2271. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780122404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing, R foundation for statistical computing. Vienna (Austria): 2012. Available at: http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Neill CJ, Deavers MT, Malpica A, Foster H, McCluggage WG. An immunohistochemical comparison between low-grade and high-grade ovarian serous carcinomas: significantly higher expression of p53, MIB1, BCL2, HER-2/neu, and C-KIT in high-grade neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1034–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schorge JO, McCann C, del Carmen MG. Surgical Debulking of ovarian cancer: what difference does it make? Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2010;3:111–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singer G, Shih IEM, Truskinovsky A, Umudum H, Kurman RJ. Mutational analysis of K-ras segregates ovarian serous carcinomas into two types: invasive MPSC (low-grade tumor) and conventional serous carcinoma (high-grade tumor) Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2003;22:37–41. doi: 10.1097/00004347-200301000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singer G, Stöhr R, Cope L, Dehari R, Hartmann A, Cao DF, et al. Patterns of p53 mutations separate ovarian serous border-line tumors and low- and high-grade carcinomas and provide support for a new model of ovarian carcinogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:218–224. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000146025.91953.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santillan A, Kim YW, Zahurak ML, Gardner GJ, Giuntoli RL, 2nd, Shih IM, et al. Differences of chemoresistance assay between invasive micropapillary/low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma and high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:601–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farley J, Brady WE, Vathipadiekal V, Lankes HA, Coleman R, Morgan MA, et al. Selumetinib in women with recurrent low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:134–140. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70572-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]