Abstract

Stroke survivors often recover from motor deficits, either spontaneously or with the support of rehabilitative training. Since tonic GABAergic inhibition controls network excitability, it may be involved in recovery. Middle cerebral artery occlusion in rodents reduces tonic GABAergic inhibition in the structurally intact motor cortex (M1). Transcript and protein abundance of the extrasynaptic GABAA-receptor complex α4β3δ are concurrently reduced (δ-GABAARs). In vivo and in vitro analyses show that stroke-induced glutamate release activates NMDA receptors, thereby reducing KCC2 transporters and down-regulates δ-GABAARs. Functionally, this is associated with improved motor performance on the RotaRod, a test in which mice are forced to move in a similar manner to rehabilitative training sessions. As an adverse side effect, decreased tonic inhibition facilitates post-stroke epileptic seizures. Our data imply that early and sometimes surprisingly fast recovery following stroke is supported by homeostatic, endogenous plasticity of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors.

Stroke is the major cause of an acquired lifelong physical disability1. As a further complication, patients surviving brain ischemia often develop enhanced brain excitability and epileptic seizures, which negatively affect functional outcomes and have a considerable social and psychological impact on stroke patients2.

Motor impairments, including sensorimotor failures, hemiparesis, ataxia and spasticity, are the most common deficits after stroke and affect up to 80% of patients3. Spontaneous functional recovery frequently occurs following stroke4, and lesion-induced brain plasticity can be used to restore function5,6, especially if early rehabilitative training is performed7,8,9. Though several studies indicate the benefits of an early mobilization, an intensive training commencing too early may have a detrimental impact on stroke recovery10. Therefore, the optimal time to start out of bed activity should be adapted to stroke severity, age as well as frequency and time of rehabilitative interventions11. Unfortunately, the extent of motor recovery is highly variable between stroke patients, and the molecular basis of this form of plasticity is still unknown.

The neural basis for motor recovery following stroke depends on brain plasticity, which defines the ability of the brain to structurally reorganize and adapt its function. Brain plasticity-dependent motor learning is mainly controlled by GABA mediated inhibition12,13. GABA, the major inhibitory transmitter in the central nervous system, activates GABAA receptors, which are composed of heterogeneous combinations of receptor subunits, to fine-tune fast synaptic inhibition and to control overall network excitability by tonic inhibition. In the cerebrum, the GABAA receptor subunits δ and α5 have been identified as specific subunits incorporated into extrasynaptic GABAA receptors that mediate tonic inhibition.

The potential pharmacological modulation of tonic inhibition has attracted considerable attention in stroke research. As a novel therapy, the administration of a benzodiazepine inverse agonist specific for the GABAA receptor subunit α5 (L655,708) has been suggested to reduce excessive tonic inhibition found in the peri-infarct cortex following photothrombotic injury14. In light of enhanced lesion-induced plasticity5,6 and the occurrence of well-known post-stroke epilepsy2,15, the observation of increased brain inhibition following stroke is surprising.

Indeed, by screening of transcriptome data, we found a significant decrease of the extrasynaptically localized GABAA receptor subunit δ following stroke in mice16. Stroke was induced by reversible occlusion of the middle cerebral artery in mice. The majority of strokes in humans (over 80%) are ischemic strokes resulting from blockage of blood vessels in the brain17. Since most ischemic strokes occur in the territory of middle cerebral artery, occlusion of this artery in mice is perfectly suitable to model focal brain ischemia in humans18. A decrease in tonic GABAergic inhibition following ischemic stroke may contribute to the described period of post-stroke plasticity and therefore may enhance the efficacy of rehabilitative therapies or even mediate spontaneous functional recovery5. Moreover, an attenuated tonic inhibition may facilitate seizures, which occur as a complication of stroke. We here studied tonic inhibition as a possible mediator of post-stroke brain hyperexcitability.

Our data indicate that following stroke the brain itself down-regulates tonic GABAergic inhibition and produces an environment, which supports brain plasticity and thereby facilitates motor improvements. In agreement with this, a decrease in tonic inhibition was identified as a reason for post-stroke epileptic seizures. As mechanism for the impaired tonic inhibition, we identified the activation of NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptors by stroke-induced excitotoxicity.

Results

Tonic GABAergic inhibition is decreased after stroke, which correlates with a reduction of δ-GABAARs

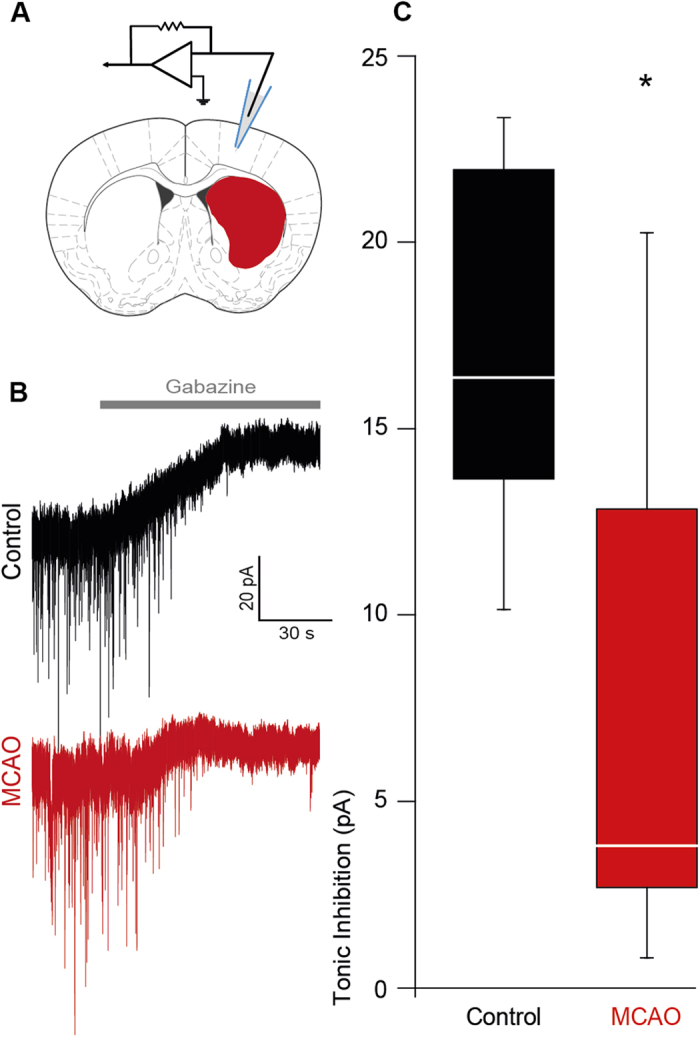

We examined GABAA receptor-mediated tonic inhibition in the peri-infarct motor cortex of mice following stroke. Occlusion of the MCA for 30 min resulted in subcortical restricted lesions surrounded by an extensive penumbra. Whole cell voltage clamp recordings were performed on layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons of the motor cortex (M1). Beside their unique morphological specificities, the input resistance (control: Rin 60.6 ± 7.3 MΩ; MCAO: Rin 77.0 ± 9.2 MΩ) was in the typical range for pyramidal cells19. Layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons revealed a decrease of tonic inhibition following MCAO at day 7 of reperfusion [controls: 16.37 ± 1.79 pA; MCAO: 3.81 ± 2.64 pA]. In total, 7 cells of 3 mice with stroke, and 7 cells of 3 control animals were analyzed (cells n = 7 each, mice n = 3 each, p ≤ 0.05; Fig. 1). At the contralateral side, 6 cells of 3 MCAO mice were analyzed, which were not significantly different to controls [23.01 ± 9.16 pA].

Figure 1. Diminished tonic inhibition in the peri-infarct cortex following stroke.

(A) Electrode position for patch-clamp experiments, modified from The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates70. (B) Representative traces showing tonic inhibitory currents in control and peri-infarct neurons, respectively. (C) Box plot (boxes: 25–75%, whiskers: 10–90%, lines: median) showing significantly diminished tonic inhibition in the peri-infarct cortex 7 days after MCAO [MCAO, controls (cells n = 7 each, mice n = 3 each) *p ≤ 0.05].

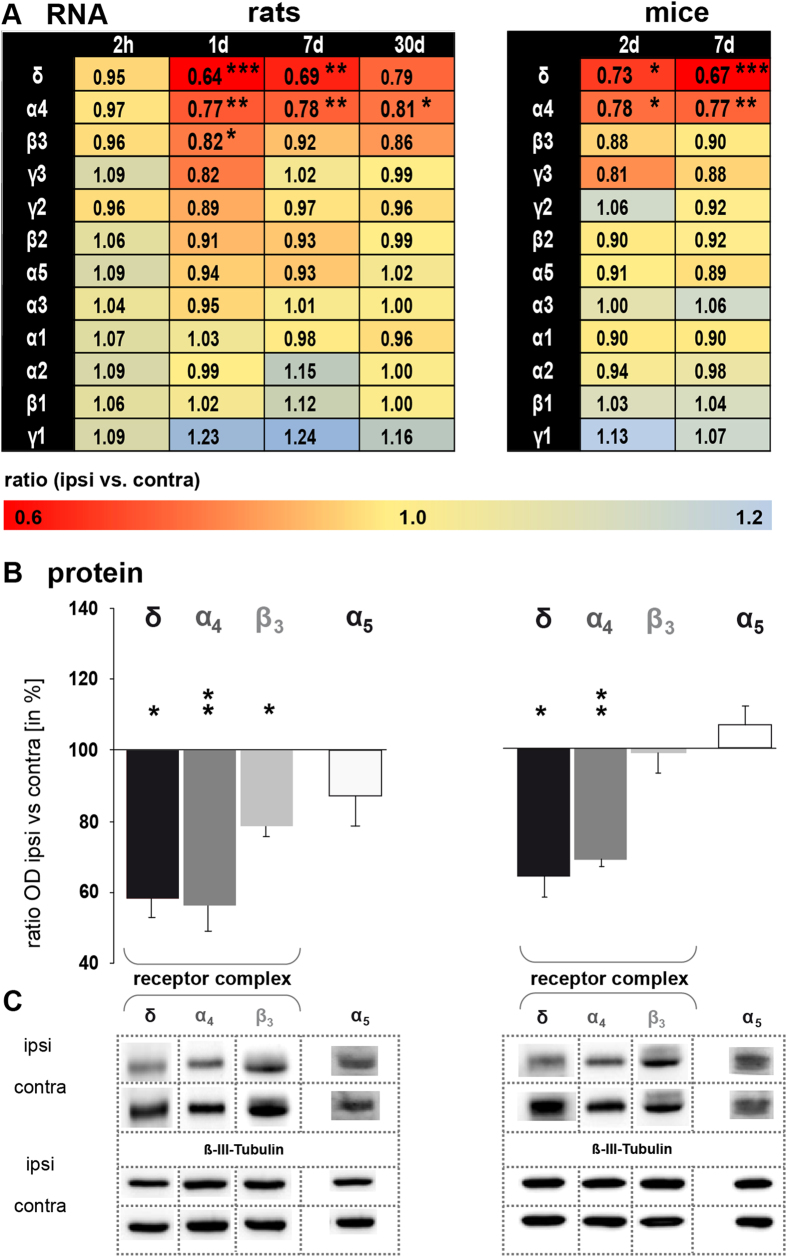

Reduction of tonic inhibition was paralleled by a significant down-regulation of GABAA receptor subunit δ transcripts (Gabrd) and protein (GABRD) in peri-infarct tissue 7 days after stroke in mice [Gabrd ratio ipsi- vs. contralateral: 0.67 ± 0.06 (n = 4), p ≤ 0.001, and GABRD ipsi- vs. contralateral: 64.39 ± 5.93% (n = 4), p ≤ 0.05, Fig. 2A,B] as well as in rats [Gabrd ratio ipsi- vs. contralateral: 0.69 ± 0.10 (n = 6), p ≤ 0.01, and GABRD ipsi- vs. contralateral: 58.29 ± 5.01% (n = 5), p ≤ 0.05, Fig. 2A,B]. Expression changes of Gabrd were further specifically investigated in the M1 of mice, where we confirmed a significant down-regulation at 7 days after reperfusion (ratio ipsi- vs. contralateral: 0.83 ± 0.04 (n = 8), p ≤ 0.05). Reduction of Gabrd transcript abundance started with a delay of several hours and recovered in the subsequent four weeks (Fig. 2A). The contralateral side of sham-operated mice did not show expression differences compared to the contralateral side of MCAO mice. No change of Gabrd was observed in occipital brain tissue, i.e., remote from the lesion and outside of the penumbra (visual cortex at 7 days of reperfusion: ratio ipsi- vs. contralateral: 1.07 ± 0.10% (n = 5). The down-regulation of δ-subunits was further corroborated by decreased transcript and protein levels for α4 and β3, the most abundant co-subunits of δ in the cerebrum20 (Fig. 2A,B). Expression of subunits α5 was unchanged at the RNA and protein level at all time-points analyzed (Fig. 2A,B).

Figure 2. Stroke down-regulates extrasynaptically located GABAA receptors containing the δ subunit.

(A) qPCR analysis revealed a significant decrease of subunit δ, α4 and β3 transcript abundance. Transcript abundance of all other GABAA receptor subunits tested remained stable. Data were normalized to Tubb3 and displayed as the geomean of ratios ± s.e.m. [rats (n = 6), mice (n = 4), ipsi vs. contra, *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001]. Left column: rats; right column: mice (B) Western blot analysis revealed a significant decrease of subunits δ, α4 and β3 and an unaltered expression of subunit α5 7 days after MCAO. Data were normalized to ß-III-Tubulin. Ratios of optical densities are shown as the percent relative to the contralateral hemisphere. Bars represent the mean ± s.e.m. [rats (n = 5), mice (n = 4), ipsi vs. contra, *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01]. (C) Representative protein bands are shown. Selected protein bands were cropped as indicated by dotted lines. All gels were run under the same experimental conditions. Ipsi- and contralateral brain samples from the same animal processed for one receptor subtype were always run on the same gel. Used antibodies and protein size of GABA receptor subunits (in kDa) are summarized in Supplementary table 1.

Stroke-induced activation of NMDA receptors down-regulates Kcc2 and Gabrd

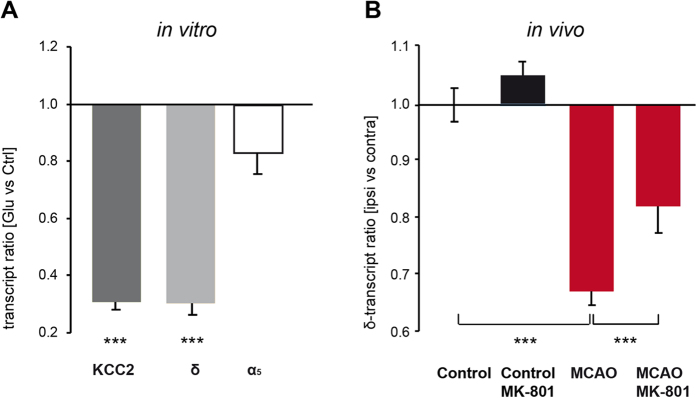

Glutamate application (20 μM) to cultured cortical neurons decreased Kcc2 transcript abundance [ratio of glutamate (n = 11) vs. control (n = 8): 0.31 ± 0.03, p ≤ 0.001, Fig. 3A]. Likewise, Gabrd transcripts were reduced [ratio of glutamate (n = 11) vs. control (n = 8): 0.30 ± 0.04, p ≤ 0.001, Fig. 3A]. Glutamate treatment had no effect on the expression of Gabra5 [glutamate (n = 7) vs. control (n = 6), Fig. 3A].

Figure 3. Activation of NMDA receptors by glutamate induces a down-regulation of Kcc2 and Gabrd transcripts.

(A) Application of glutamate (20 μM) to cultured cortical neurons decreased Kcc2 and Gabrd but had no effect on Gabra5. Transcript abundance was determined one day after glutamate treatment. Data were normalized to Tubb3 and displayed as the geomean of ratios ± s.e.m. [glutamate vs. controls, cell culture experiments (n = 6–11), ***p ≤ 0.001]. (B) Blocking the NMDA-receptors with MK-801 attenuated the post-ischemic down-regulation of Gabrd. MK-801 was injected at the onset of reperfusion. Transcript expression was determined 7 days later. Bars represent the geomean ± s.e.m. [control mice (n = 5), control + MK-801 (n = 7), MCAO (n = 9), MCAO + MK-801 (n = 7), ipsi vs. contra, ***p ≤ 0.001].

Next, we tested the pathophysiological role of excessive NMDA-receptor stimulation during stroke in vivo. We applied the non-competitive NMDA-receptor antagonist MK-801 to MCAO mice. Using 1 mg/kg MK-801 (given i.p. at the beginning of reperfusion), MK-801 did not affect infarct size. In control mice, MK-801 had no impact on subunit δ expression [control mice (n = 5), control + MK-801 (n = 7), Fig. 3B]. However, MK-801 significantly attenuated the post-ischemic down-regulation of Gabrd transcripts 7 days after MCAO [ratio ipsi- vs. contralateral MCAO: 0.65 ± 0.03 (n = 9), MCAO + MK-801: 0.81 ± 0.05 (n = 7), p ≤ 0.001 Fig. 3B]. Taken together these data suggest a glutamate-driven post-stroke mechanism of δ-GABAARs down-regulation, finally leading to decreased tonic inhibition.

Synaptically localized GABAA receptor subunits are unchanged after stroke

Heterogeneous combinations of synaptic GABAA receptor subunits [α(1–4), β(1–3), γ(1–3), typically 2α:2β:1γ]20,21 provide the basis for fine-tuning of fast synaptic GABAergic inhibition. With the present approach, we found no changes in mRNA levels of synaptically localized GABAA receptor subunits (α1, α2, α3, β1, β2, γ1, γ2, and γ3) following mild MCAO [rats (n = 6), mice (n = 4), Fig. 2A). Intracellular recordings of principal neurons in the cortical layer 2/3 demonstrated that the frequency of spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) was reduced, while amplitudes or receptor kinetics were unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 1), suggesting a pre-synaptic, receptor-independent change of fast synaptic inhibition.

A recent study revealed an increased phasic GABAergic signaling following permanent stroke, photothrombosis and distal MCAO. This enhanced inhibition was identified in cortical layer 5 (but not in layer 2/3) pyramidal neurons located in a small peri-lesional rim (800 μm). In accordance, the number of α1 receptor subunit containing synapses was increased in layer 5. Chronic treatment with a low dose of zolpidem, a positive allosteric modulator with high affinity for α1-GABAARs, enhanced functional recovery22. Unpublished data from own experiments confirm an up-regulation of α1 and other synaptically localized subunits in a small rim surrounding the lesion (cf. Figs 2 and 4 in Redecker et al.)23.

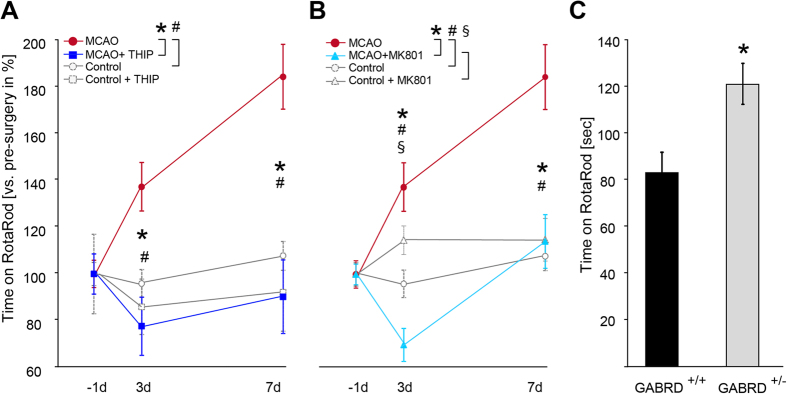

Figure 4. Diminished tonic GABAergic inhibition promotes post-stroke motor function.

(A) Mice showed improved RotaRod performance 3 and 7 days after stroke [controls (n = 14), MCAO (n = 8–10), #p ≤ 0.01]. Post-stroke activation of δ-GABAARs via gaboxadol (THIP) reduced motor function to control levels [MCAO (n = 8–10), MCAO + THIP (n = 8), *p ≤ 0.001]. THIP had no effect on motor performance in control mice (n = 5, Fig. 4A). Data points represent the mean ± s.e.m. [time on RotaRod vs. pre-surgery in percent]. (B) NMDA-receptor blockade by MK-801 reversed the improved RotaRod performance at 3 and 7 days following stroke. Bars represent the mean ± s.e.m. [control mice (n = 15), control + MK-801 (n = 14), MCAO (n = 8–10), MCAO + MK-801 (n = 12), *p ≤ 0.001, #p ≤ 0.05 at 3 days, #p ≤ 0.001 at 7 days, §p ≤ 0.001 at 3 days). (C) Motor function as assessed by RotaRod was better in GABRD+/− mice compared to their wild-type littermates (GABRD+/+). Bars represent the mean ± s.e.m. [time on RotaRod in sec, GABRD+/+, GABRD+/− (n = 11 each), *p ≤ 0.01].

Decreased tonic inhibition following MCAO is associated with better RotaRod performance

General locomotor activity after MCAO was analyzed by a walking test. Mice with MCAO displayed a significant reduced walking distance and reduced velocity compared to their controls [total distance in cm 3 days after stroke: controls (n = 5): 1435.39 ± 139.97, MCAO (n = 9): 939.98 ± 112.60, 7 days: controls: 1297.77 ± 38.50, MCAO: 914.14 ± 116.04; velocity in cm/sec 3 days: controls: 4.80 ± 0.47, MCAO: 3.14 ± 0.38; 7 days: controls: 4.33 ± 0.13; MCAO: 3.05 ± 0.39, *p ≤ 0.05]. The impact of diminished tonic inhibition on post-stroke functional motor performance was subsequently analyzed using an accelerated RotaRod test24, in which the mice are forced to move similar to rehabilitative training sessions to evaluate their motor coordination and balance. In our subcortical stroke model, motor performance was surprisingly strongly improved after MCAO [time on RotaRod vs. pre-surgery in percent: 3 days after stroke: 137.20 ± 10.36% and 7 days after stroke: 184.16 ± 13.81%, controls (n = 14), MCAO (n = 8–10), p ≤ 0.01; Fig. 4A]. In contrast, stroke models that destroy cortical motor regions reveal impairments on RotaRod25,26. Because the cortex was structurally intact in the present study, the impressive improvement suggests functional changes in the motor cortex, which may be related to decreased tonic inhibition. Indeed, 5 mg/kg gaboxadol (THIP), a muscimol analogue that activates extrasynaptic GABAA receptors containing the δ subunit27,28, abolished the improvement of RotaRod performance in MCAO mice [3 days after stroke: 77.70 ± 12.45% and 7 days after stroke: 90.29 ± 15.72% (n = 8), Fig. 4A]. THIP had no effect on motor performance in control mice (n = 5, Fig. 4A), in agreement with previous studies29,30. Based on published data obtained from rat, subcutaneous administration of 5 mg/kg THIP induces brain levels of approximately 1,4 μM after 60 min31. This comparatively low concentration did not activate synaptic receptors (tested for α1β3γ2) but selectively agonizes α4β3δ below the superagonist behaviour which may be observed with concentrations exceeding 10 μM32.

Next, we analyzed the impact of the NMDA-receptor blockade on motor performance after stroke by employing the RotaRod test. MK-801 administration to MCAO mice prevented the improvement of motor performance following stroke [3 days after stroke: 69.92 ± 7.03% and 7 days after stroke: 114.05 ± 11.41 (n = 12), Fig. 4B], while it had no effect in control mice (n = 14, Fig. 4B). We conclude that the improved motor coordination early after stroke is caused by a lesion-induced plasticity mediated by the activation of NMDA-receptors with a subsequent decrease of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors. Our finding that post-stroke down-regulation of δ-GABAARs is responsible for the improved motor performance could further be corroborated by the better RotaRod performance of GABRD+/− vs. wild-type mice [GABRD+/+: 82.63 ± 8.81 sec, GABRD+/−: 121.12 ± 5.10 sec (n = 11 each), p ≤ 0.01; Fig. 4C].

Reduced tonic inhibition after stroke promotes epileptic seizures

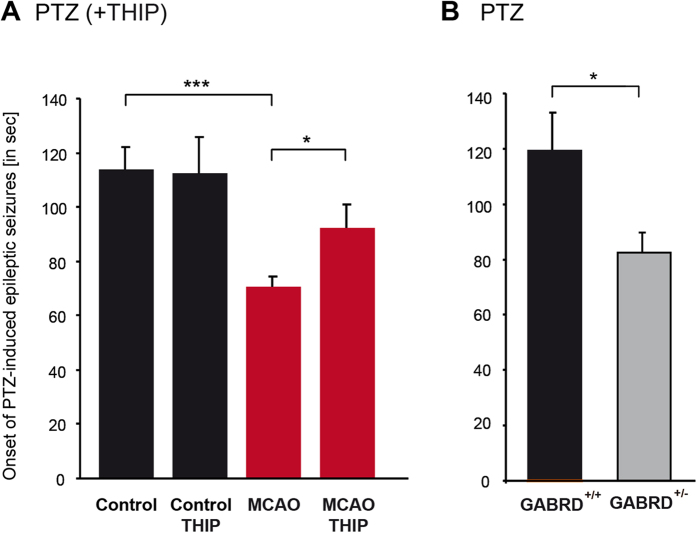

Post-stroke reduction of tonic inhibition may be expected to enhance seizure susceptibility. To test this hypothesis, we injected pentylenetetrazole (PTZ, 60 mg/kg) and determined the interval after which epileptic seizures appeared33. Seven days after MCAO, seizure susceptibility was significantly enhanced [controls: 113.75 ± 8.38 sec (n = 6); MCAO: 70.59 ± 3.56 sec (n = 11), p ≤ 0.01; Fig. 5A]. The post-ischemic application of 5 mg/kg gaboxadol (THIP), to activate extrasynaptic δ-GABAARs, delayed the onset of seizures in response to PTZ in MCAO mice [92.26 ± 8.83 sec, (n = 10), p ≤ 0.05; Fig. 5A) but had no effect on the onset of epileptic discharges in control mice (n = 6, Fig. 5A)34. The impact of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors on the seizure threshold was corroborated by experiments on transgenic mice with reduced expression of the δ subunit: GABRD+/− mice displayed a higher seizure susceptibility than control mice [GABRD+/+: 119.78 ± 13.20 sec (n = 4); GABRD+/−: 82.46 ± 7.35 sec (n = 9), p ≤ 0.05; Fig. 5B). These results revealed a down-regulation of extrasynaptic δ-GABAARs as a cause of post-stroke seizures.

Figure 5. Stroke facilitates the onset of PTZ induced seizures.

(A) Time to onset of epileptic seizures was reduced 7 days after MCAO. This effect was antagonized by gaboxadol (THIP), specifically activating extrasynaptic δ-GABAARs. THIP had no effect in control mice. Bars represent the mean ± s.e.m. [control (n = 6), control + THIP (n = 6), MCAO (n = 11), MCAO + THIP (n = 10), *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01]. (B) Time to onset of epileptic seizures was also reduced in GABRD+/− mice compared to their wild-type littermates (GABRD+/+). Bars represent the mean ± s.e.m. [GABRD+/+ (n = 4), GABRD+/− (n = 9), *p ≤ 0.05].

Discussion

Tonic GABAergic inhibition is down-regulated following stroke

Here, we identified a decrease of tonic GABAergic inhibition following MCAO in adult mice by patch-clamp recordings in the motor cortex (M1). This reduction was paralleled by a down-regulation of the extrasynaptically localized GABAA receptor subunit δ as well as by a decrease of its α4 and β3 co-subunits. We considered glutamate-driven excitotoxicity, which plays a key role in ischemic brain injury, as a potential mechanism of down-regulation35. Previous studies showed that NMDA receptor activity36,37, as well as stroke38, down-regulate the neuron-specific K+ Cl− co-transporter KCC2, which in turn is associated with a decreased expression of δ-containing GABAA receptors39. We tested our hypothesis that glutamate induces the down-regulation of δ-GABAARs via a KCC2-mediated mechanism in a cell culture model. Glutamate application to cortical neurons markedly decreased transcript expression of Kcc2 and Gabrd. Because administration of the NMDA-receptor antagonist MK-801 to MCAO mice significantly attenuated the post-ischemic down-regulation of δ-GABAARs, an excitotoxicity-driven mechanism is corroborated in vivo.

Several cerebral pathophysiologies that are associated with excitotoxicity e.g., ischemia38,40, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis41 and epilepsy36, lead to down-regulation of KCC2. Mechanisms identified for KCC2 down-regulation include calpain-dependent cleavage37, phosphorylation of KCC2 at tyrosine 903/108742 as well as dephosphorylation at serine 94043 and BDNF-induced TrkB activation44. Although most of these mechanisms point to post-translational processes, we and others have revealed an excitotoxicity-associated down-regulation of KCC2 already at the transcript level44. The contribution of the neuronal Cl−-extrusion in overall GABAergic inhibition has been extensively described, but less is known concerning KCC2 function and tonic inhibition. A recent study investigated KCC2-mediated intracellular chloride levels as possible regulators of the developmental switch in GABAA receptor subunits. They found that tonic current amplitudes and the surface expression of the δ subunit decreased following KCC2 shRNA transfection39, which indicates a KCC2-mediated mechanism of GABRD regulation. In contrast, studies on KCC2-mutant mice (15–20% remaining cerebral KCC2 expression) suggest that tonic inhibition is not affected45. Here, we demonstrate a simultaneous down-regulation of both transcripts under conditions of excitotoxicity, but if and how KCC2 specifically regulates δ-GABAARs remains elusive.

After photothrombotic stroke, a model which is virtually devoid of a penumbra6, enhanced tonic inhibition was described in a narrow rim surrounding the lesion14. This enhancement of tonic inhibition is due to impaired uptake of GABA via GAT-3/GAT-414. We confirmed significant decreased GAT3/4 expression in peri-infarct tissue following photothrombosis but did not detect a change in GAT3/4 expression following MCAO (Supplementary Fig. 2). The expression of Gabrd and Gabra5 was unchanged following photothrombosis in several peri-lesional and remote brain regions in adult mice (Supplementary Fig. 2). Earlier work from our laboratory yielded variable results with respect to α5 subunit expression following a photothrombotic stroke: while Redecker et al.23 observed a down-regulation in the peri-lesional rat cortex, Schmidt et al.46 described non-significant changes in young rats, but an up-regulation in aged rats. The variability with respect to the regulation of α5 subunits may partially be attributed to the comparatively low expression in the cortex. Gabra5 RNA and protein expression were unaffected following MCAO. This does not exclude that a further pharmacological reduction of tonic inhibition mediated by α5-GABAARs may augment functional recovery14, although at the risk of inducing epileptic activity.

In conclusion, the change of excitability may therefore depend on the type of the ischemic lesion especially with respect to glial scar formation and thus contribute to the observed clinical variability.

Stroke-induced down-regulation of tonic inhibition is associated with a better motor performance on the RotaRod

Following MCAO, a walking test revealed decreased general motor activity but when mice were forced to move on a RotaRod at 3 and 7d following stroke they behaved better than controls. The improved RotaRod performance stands in apparent contradiction to previous results. First, enhancement in motor coordination requires a morphological intact M1, a region that is mainly involved in RotaRod training47. Own observations in MCAO mice with cortical damage revealed an impaired RotaRod performance following stroke (unpublished data) in agreement with other studies25,48,49. Second, in our model, lower post-ischemic tonic GABAergic inhibition in the M1 underlies this improved motor performance. Blockade of the excitotoxicity-mediated decrease in tonic inhibition by MK-801 or a post-stroke activation of tonic inhibition via gaboxadol (THIP) reduced RotaRod performance to control levels. Third, the RotaRod test we used provided a good grip on the rod and; similar to rehabilitative training sessions, the mice are forced to move. Our observation are further in agreement with reports that describe a period of enhanced brain plasticity following stroke5.

GABA is known to be intimately involved in motor learning as well as in rehabilitation following stroke. Healthy volunteers with a better performance in motor learning had a greater decrease in their GABA levels in response to transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS)12. Stroke itself is known to diminish GABA, and lower levels of GABA are associated with better recovery in stroke patients50. Therefore, the ability to decrease cortical GABA is important to facilitate motor skills in humans. The post-stroke decrease in GABA was localized to the ipsilateral M150, the cortical region where we identified a decrease in δ-subunits in association with attenuated tonic inhibition. Decreased GABA in M1 might be an additional source of impaired tonic inhibition.

While several studies point to an advantage of a decrease in GABAergic inhibition to facilitate motor skills, the specific relevance of tonic inhibition in this context remains uncertain. Blocking of excessive tonic inhibition was beneficial for the recovery of motor functions following photothrombotic stroke14 and suppressed hyperactivity in an animal model of Down syndrome51. In both studies, the effect was mediated by negative allosteric modulators (or benzodiazepine-site inverse agonists) selective for α5-GABAARs. Following a unilateral lesion of the anteromedial cortex, ipsilateral muscimol infusions disrupted the recovery from somatosensory asymmetry52. Muscimol acts as a super agonist on δ-GABAARs with increased efficacy compared to GABA53. In contrast, the potentiation of tonic inhibition via gaboxadol (THIP, a muscimol analogue) reduced cerebellar ataxia in an animal model of Angelman syndrome54 and attenuated motor hyperactivity in the mouse model of Fragile X Syndrome55. Moreover, an increase in extrasynaptic GABA is involved in the control of motor excitability observed in Tourette syndrome56.

These studies revealed the tight homeostatic control of motor functions by GABAergic tonic inhibition because variations above and below trigger motor dysfunctions. In our model, decrease of tonic inhibition facilitates motor improvements. We therefore suggest that higher cortical excitability induces a homeostatic plasticity that can be used for rehabilitation. Whereas this is in agreement with the accepted role of GABA in controlling excitability, the specific impact of GABAergic tonic inhibition on the emerging post-stroke motor plasticity is new. Moreover, we suggest that the regulation of tonic inhibition following stroke might be a reason for the inter-individual differences in behavioral performance and recovery. This is supported by our results that reveal an attenuated decrease of Gabrd following stroke in aged vs. young mice16, which suggests a reduced cortical plasticity and less frequent spontaneous recovery in the elderly.

Stroke facilitates the onset of epileptic seizures

Patients surviving brain ischemia often develop enhanced brain excitability and epileptic seizures2. Post-stroke seizures are treated like epilepsy with all the negative side effects of anticonvulsants like a harmful impact on functional recovery, cognition, bone health and interference with other medications. Therefore negative effects of anti-epileptic drugs stand against the potential benefits of seizure reduction.

We therefore studied tonic inhibition as a possible mediator of post-stroke brain hyperexcitability. PTZ administration promoted the onset of epileptic seizures in mice after MCAO. This effect was abolished by the post-ischemic application of gaboxadol (THIP). We also confirmed the impact of lower tonic inhibition on seizure thresholds in GABRD+/− mice, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies on GABRD−/− mice57.

Missense mutations within the human GABRD gene tend to decrease GABAAR function and are found to be associated with generalized idiopathic epilepsies58,59,60. Therefore, it is not surprising that ambient GABA and extrasynaptically localized GABAARs are targets of anticonvulsant drugs61. Although we identified post-stroke epileptic seizures as THIP sensitive, we cannot exclude the down-regulation of KCC2 as a further cause of enhanced brain activity. Its knockdown in mice increases neuronal excitability, and rare variants of KCC2 confer an increased risk of epilepsy in men62.

Here, we identified a decrease in GABAergic tonic inhibition as a cause of epileptic seizures following stroke. This is important because it opens the possibility of specifically treating severe post-stroke seizures and thereby omitting the side effects that often emerge from anticonvulsants. Gaboxadol (THIP), a muscimol derivative, is an attractive candidate in this context.

Survivors of stroke often recover from motor deficits, either spontaneously or during early rehabilitative training4,7,8,9. Unfortunately, the extent of motor recovery is highly variable between stroke patients as well as their responsiveness to rehabilitative therapies. We identified decreased GABAergic tonic inhibition as the molecular basis of post-stroke plasticity. The regulation of tonic inhibition following stroke might be a reason for the inter-individual differences in patient recovery and the occurrence of epileptic seizures. Therefore, our findings have important implications for the rehabilitation of stroke patients.

Methods

Animals

All studies were performed on 2–3-month-old male Wistar rats and C57Bl/6J mice. All animal care and experimental procedures were performed in accordance with EU animal welfare protection laws and regulations. We confirm that all experimental protocols were approved by a licensing committee from the local government (Landesamt für Verbraucherschutz, Bad Langensalza, Thuringia, Germany). GABAA receptor subunit δ - deficient mice; GABRD+/− 63 were kindly provided by W. Sieghart, University of Vienna, Austria.

Transient MCA occlusion (MCAO)

MCAO was performed as described in detail for rats64 and mice65. Occlusion of the MCA was performed for 30 min. The protocol of a mild MCAO we applied here produces infarcts which are mainly restricted to the territory of the MCA and therefore affect the striatum, but does not damage the thalamus. The rat brains were removed after cervical dislocation at two hours, one day, 7 and 30 days after reperfusion. Using a rat brain slicer (Rodent Brain Matrix, Adult Rat, Coronal Sections; ASI Instruments, USA), coronal sections (3 mm) comprising the infarct (bregma 1.0 to −2.0 mm) were dissected and subsequently separated into the ipsi- and contralateral hemisphere. The mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation with subsequent brain removal on day 2 and 7 after reperfusion. Using a Precision Brain Slicer (BS-2000C Adult Mouse; Braintree Scientific Inc., USA), coronal sections (2 mm) comprising the infarct (bregma +0.8 to −1.2 mm) were separated into the contra- and ipsilateral hemisphere, hereafter referred to as peri-infarct tissue.

Photothrombotic lesions

Photothrombosis was induced in anaesthetized mice by fixing the head in a stereotactic frame. A fiberoptic bundle (diameter 1.3 mm) connected to a cold light source (KL 1500; Schott, Germany) was positioned in the middle between the bregma and lambda, 1.5 mm lateral to the mid-sagittal suture. Following Bengal Rosa administration into the tail vein (50 mg/kg body weight), the skull was illuminated for 15 min. The controls underwent the same procedure but without illumination. The brains were removed after cervical dislocation 7 days following injury induction. Specific brain regions were dissected.

Slice preparation and patch-clamp recordings

Patch-clamp recordings were performed as described previously66. Coronal brain slices of mice were prepared 7 days after MCAO. Briefly, cortical layer 2/3 neurons were patched using a CsCl-based intracellular solution (in mM): 122CsCl, 8NaCl, 0.2MgCl2, 10HEPES, 2EGTA, 2Mg-ATP, 0.5Na-GTP, pH adjusted to 7.3 with CsOH in the whole-cell modus at a holding potential of −70 mV. DL-APV (30 μM), CNQX (10 μM) and GABA (5 μM) were added to aCSF. Total GABAergic currents consisting of both phasic and tonic components were blocked by the application of 100 μM gabazine. The size of the tonic inhibitory current was determined by subtracting the holding current under baseline conditions from the holding current in the presence of gabazine. Holding currents were estimated by plotting 20 sec periods of raw data in an all-points histogram (Clampfit 10.2; Molecular Devices). A Gaussian line was fitted to the right part of the smoothed curve (Savitzky-Golay algorithm), which was not skewed by synaptic events. The mean of the fitted Gaussian line was considered the mean holding current67. Recordings of sIPSCs were performed using the same intracellular solution as for the determination of the tonic inhibition. DL-APV (30 μM), CNQX (10 μM) and GABA (5 μM) were added to the perfusate. The currents were identified as events when the rise time was faster than the decay time. The following parameters were determined: inter-event interval, frequency, rise time, peak amplitude and the time constant of decay (τ). The decay of each event was fitted with a monoexponential curve in pClamp. Only residual SDs <0.3 were accepted as a criterion for the quality of the fit.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) or using the phenol/chloroform extraction method. qPCR was performed as described previously65. The specific primers are listed in Supplementary Table 1. qPCR was performed in a 20 μl amplification mixture consisting of Brilliant® II or III SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix (Stratagene, USA), cDNA (equivalent to 25 ng reverse-transcribed RNA) and primers (at a final concentration of 250 nM each). Specific transcripts were amplified with Rotor Gene 6000 (LTF-Labortechnik/Corbett Life Science, Australia). Expression of each GABAA receptor subunit was normalized to Gapdh as well as to Tubb3. The relative expression levels (MCAO ipsi vs. contra and MCAO contra vs. sham contra) were calculated using the Pfaffl equation68.

Western blot analyses

Protein isolation and Western blotting were performed as described previously38. Whole proteins were isolated and equal amounts of protein (10 μg each) were applied. The antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Proteins were detected by chemiluminescence (Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate; Millipore, Germany) and analyzed with the image acquisition system LAS 3000 (Fujifilm, Japan). The optical density of each protein band was quantified with AIDA Image Analyzer Software (Raytest, Germany). Optical densities were normalized to ß-actin as well as to ß-III-Tubulin.

Neuronal cell culture

Cortical neurons were dissected from mouse embryos as described previously66,69. In brief, brain tissues from 2–3 embryos (E18+/−1day) were removed and transferred into fresh 1× Hanks’ balanced salt solution on ice (HBSS, Gibco). Dissected cortices were rinsed with HBSS and were trypsinized with 0.25% trypsin at 37 °C for 30 min. The supernatant was removed, and the cortices were washed with HBSS and passed through Pasteur pipettes of decreasing diameter to dissociate the tissue. Approximately 250,000 cells were plated onto poly-L-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich)-coated coverslips (ø 30 mm). Cells were allowed to settle for 120 min at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in the incubator. Finally, coverslips were transferred to 6 cm culture dishes containing Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1 mM L-glutamine, B27 supplement (Gibco), and penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco). Medium was added once a week, and the cultures were maintained for 3 weeks before the experiments. At DIV17–18, cells were incubated with 20 μM glutamate for 10 min. Twenty-four hours later, cells were harvested in Qiazol (3 coverslips each were pooled as one RNA sample) and processed for RNA isolation and qPCR as described above.

Pharmacological interventions in vivo

Tonic inhibition was modulated by the GABAA receptor agonist gaboxadol (also known as 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo(5,4-c)pyridin-3-ol THIP, Tocris Bioscience, UK). THIP was administered i.p. at a dose of 5 mg/kg BW 30 min before starting the RotaRod tests and 30 min before epilepsy induction. MK-801, a non-competitive antagonist of NMDA- receptors, was administered i.p at a dose of 1 mg/kg BW at the beginning of reperfusion. Control groups received physiological saline.

Behavioral studies

A walking task was performed to assess the locomotor activity of mice 3 and 7 days following MCAO. The walking apparatus consisted of a Plexiglas box equipped with a 12-mm square wire mesh with a grid area of 40 × 40 cm, 10 cm above the ground. A Panasonic Color CCTV Camera (Model No. WV-CP 450)/G) was fixed above the walking grid. Each mouse was placed individually on top of the grid and allowed to walk for 5 min. To assess the total distance, the moving time and the velocity, the Ethovision XT 6.1.326 software (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, The Netherlands) was used. Motor performance was tested by an accelerated RotaRod procedure 3 and 7 days after MCAO. The RotaRod apparatus (3375-4R; TSE Systems, Germany) consisted of a striated rod providing a good grip (diameter: 3 cm), separated in four compartments (width: 8.5 cm) and located 27.2 cm above the floor grid. One day before MCAO induction, mice were placed on the rod for 30 sec without rotation followed by 120 sec of low speed rotation at 4 rpm. Subsequently, the mice were tested in 3 trials for 5 min (4–40 rpm). After MCAO, the mice were tested under the same conditions at 3 and 7 days of reperfusion. At each trial, the latency to fall was recorded.

Induction of epileptic seizures

Post-ischemic seizures were induced in mice 7 days after MCAO using PTZ (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). PTZ was administered i.p. at 60 mg/kg BW. Immediately after PTZ injection, the mice were placed into a video-monitored Plexiglas cage, and the convulsive behavior was observed for a period of 15 min. Native and sham-operated mice underwent the same procedure. Tonic inhibition was modulated by gaboxadol (THIP), administered i.p. at a dose of 5 mg/kg BW 30 min before PTZ injection. The control groups received physiological saline injections.

Statistical analyses

qPCR data and the parameters of the behavioral studies were analyzed with one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc Tukey’s test or with Wilcoxon’s test. For statistical analysis of the patch-clamp recordings, the Mann-Whitney test, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test or Student’s t-test was used. The onset of seizures was analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test. For Western-blot analysis, the paired Student’s t-test was used. All data are expressed as the mean or geomean ± s.e.m. The levels of significance were set at *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01 and ***p ≤ 0.001.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Jaenisch, N. et al. Reduced tonic inhibition after stroke promotes motor performance and epileptic seizures. Sci. Rep. 6, 26173; doi: 10.1038/srep26173 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ina Ingrisch, Svetlana Tausch and Annett Büschel for their technical assistance and Werner Sieghart, Center for Brain Research, Medical University Vienna, Austria for providing the GABAA subunit δ antibody and the GABRD+/− mice. This work was supported by DFG FOR 1738 B2; BMBF Bernstein Fokus (FKZ 01GQ0923); BMBF Gerontosys JenAge (FKZ 031 5581B); EU BrainAge (FP 7/HEALTH.2011.2.2.2-2 GA No. 279281); and BMBF Irestra (FKZ 16SV7209).

Footnotes

Author Contributions C.F., N.J., C.A.H. and O.W.W. designed the experiments and initiated the study. L.L. performed the patch clamp recordings. N.J. and M.G. cultured primary neuronal cells and did the entire cell culture associated experiments, as well as the walking test. N.J. performed the qPCR and Western Blot assays and applied the epilepsy model. M.G. performed qPCR and applied the RotaRod test. C.F., N.J., L.L., M.G., C.A.H. and O.W.W. analyzed the data. C.F. and O.W.W. wrote the manuscript.

References

- Donnan G. A., Fisher M., Macleod M. & Davis S. M. Stroke. Lancet 371, 1612–1623 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte O. W. & Freund H. J. Neuronal dysfunction, epilepsy, and postlesional brain plasticity. Adv Neurol 81, 25–36 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhorne P., Coupar F. & Pollock A. Motor recovery after stroke: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol 8, 741–754 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nudo R. J. Neural bases of recovery after brain injury. J Commun Disord 44, 515–520 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte O. W. Lesion-induced plasticity as a potential mechanism for recovery and rehabilitative training. Curr Opin Neurol 11, 655–662 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte O. W., Bidmon H. J., Schiene K., Redecker C. & Hagemann G. Functional differentiation of multiple perilesional zones after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 20, 1149–1165 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig L. E., Bernhardt J., Langhorne P. & Wu O. Early mobilization after stroke: an example of an individual patient data meta-analysis of a complex intervention. Stroke 41, 2632–2636 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biernaskie J., Chernenko G. & Corbett D. Efficacy of rehabilitative experience declines with time after focal ischemic brain injury. J Neurosci 24, 1245–1254 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momosaki R. et al. Very Early versus Delayed Rehabilitation for Acute Ischemic Stroke Patients with Intravenous Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator: A Nationwide Retrospective Cohort Study. Cerebrovasc Dis 42, 41–48 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad A. J., Kellner C. P., Mascitelli J. R., Bederson J. B. & Mocco J. No Early Mobilization After Stroke: Lessons Learned from the AVERT Trial. in World Neurosurg 474 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt J. et al. Prespecified dose-response analysis for A Very Early Rehabilitation Trial (AVERT). Neurology, doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002459 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagg C. J., Bachtiar V. & Johansen-Berg H. The role of GABA in human motor learning. Curr Biol 21, 480–484 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachtiar V. & Stagg C. J. The role of inhibition in human motor cortical plasticity. Neuroscience 278C, 93–104 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson A. N., Huang B. S., Macisaac S. E., Mody I. & Carmichael S. T. Reducing excessive GABA-mediated tonic inhibition promotes functional recovery after stroke. Nature 468, 305–309 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epsztein J., Ben-Ari Y., Represa A. & Crepel V. Late-onset epileptogenesis and seizure genesis: lessons from models of cerebral ischemia. Neuroscientist 14, 78–90 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber M. W. et al. Age-specific transcriptional response to stroke. Neurobiol Aging 35, 1744–1754 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom T. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 113, e85–151 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang T., Messing R. O. & Chou W. H. Mouse model of middle cerebral artery occlusion. J Vis Exp (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmstaedter M., Staiger J. F., Sakmann B. & Feldmeyer D. Efficient recruitment of layer 2/3 interneurons by layer 4 input in single columns of rat somatosensory cortex. J Neurosci 28, 8273–8284 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen R. W. & Sieghart W. GABA A receptors: subtypes provide diversity of function and pharmacology. Neuropharmacology 56, 141–148 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler H. GABA(A) receptor diversity and pharmacology. Cell Tissue Res 326, 505–516 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiu T. et al. Enhanced phasic GABA inhibition during the repair phase of stroke: a novel therapeutic target. Brain 139, 468–480 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redecker C., Wang W., Fritschy J. M. & Witte O. W. Widespread and long-lasting alterations in GABA(A)-receptor subtypes after focal cortical infarcts in rats: mediation by NMDA-dependent processes. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 22, 1463–1475 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaar K. L., Brenneman M. M. & Savitz S. I. Functional assessments in the rodent stroke model. Exp Transl Stroke Med 2, 13 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers D. C., Campbell C. A., Stretton J. L. & Mackay K. B. Correlation between motor impairment and infarct volume after permanent and transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. Stroke 28, 2060–2065; discussion 2066 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schabitz W. R. et al. Effect of brain-derived neurotrophic factor treatment and forced arm use on functional motor recovery after small cortical ischemia. Stroke 35, 992–997 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drasbek K. R. & Jensen K. THIP, a hypnotic and antinociceptive drug, enhances an extrasynaptic GABAA receptor-mediated conductance in mouse neocortex. Cereb Cortex 16, 1134–1141 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You H. & Dunn S. M. Identification of a domain in the delta subunit (S238-V264) of the alpha4beta3delta GABAA receptor that confers high agonist sensitivity. J Neurochem 103, 1092–1101 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonin R. P. et al. Pharmacological enhancement of delta-subunit-containing GABA(A) receptors that generate a tonic inhibitory conductance in spinal neurons attenuates acute nociception in mice. Pain 152, 1317–1326 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd M. B. et al. Inhibition of thalamic excitability by 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[4,5-c]pyridine-3-ol: a selective role for delta-GABA(A) receptors. Eur J Neurosci 29, 1177–1187 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremers T. & Ebert B. Plasma and CNS concentrations of Gaboxadol in rats following subcutaneous administration. Eur J Pharmacol 562, 47–52 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen M., Ebert B., Wafford K. & Smart T. G. Distinct activities of GABA agonists at synaptic- and extrasynaptic-type GABAA receptors. J Physiol 588, 1251–1268 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loscher W. Preclinical assessment of proconvulsant drug activity and its relevance for predicting adverse events in humans. Eur J Pharmacol 610, 1–11 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen S. L., Sperling B. B. & Sanchez C. Anticonvulsant and antiepileptogenic effects of GABAA receptor ligands in pentylenetetrazole-kindled mice. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 28, 105–113 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman S. M. & Olney J. W. Glutamate and the pathophysiology of hypoxic–ischemic brain damage. Ann Neurol 19, 105–111 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. H., Deeb T. Z., Walker J. A., Davies P. A. & Moss S. J. NMDA receptor activity downregulates KCC2 resulting in depolarizing GABAA receptor-mediated currents. Nat Neurosci 14, 736–743 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puskarjov M., Ahmad F., Kaila K. & Blaesse P. Activity-dependent cleavage of the K-Cl cotransporter KCC2 mediated by calcium-activated protease calpain. J Neurosci 32, 11356–11364 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenisch N., Witte O. W. & Frahm C. Downregulation of potassium chloride cotransporter KCC2 after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke 41, e151–159 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Succol F., Fiumelli H., Benfenati F., Cancedda L. & Barberis A. Intracellular chloride concentration influences the GABAA receptor subunit composition. Nat Commun 3, 738 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp E., Rivera C., Kaila K. & Freund T. F. Relationship between neuronal vulnerability and potassium-chloride cotransporter 2 immunoreactivity in hippocampus following transient forebrain ischemia. Neuroscience 154, 677–689 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs A. et al. Downregulation of the potassium chloride cotransporter KCC2 in vulnerable motoneurons in the SOD1-G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 69, 1057–1070 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. H., Jurd R. & Moss S. J. Tyrosine phosphorylation regulates the membrane trafficking of the potassium chloride co-transporter KCC2. Mol Cell Neurosci 45, 173–179 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silayeva L. et al. KCC2 activity is critical in limiting the onset and severity of status epilepticus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, 3523–3528 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera C. et al. BDNF-induced TrkB activation down-regulates the K+-Cl- cotransporter KCC2 and impairs neuronal Cl- extrusion. J Cell Biol 159, 747–752 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornberg J. et al. KCC2-deficient mice show reduced sensitivity to diazepam, but normal alcohol-induced motor impairment, gaboxadol-induced sedation, and neurosteroid-induced hypnosis. Neuropsychopharmacology 32, 911–918 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S. Bruehl C., Frahm C., Redecker C. & Witte O. W. Age dependence of excitatory-inhibitory balance following stroke. Neurobiol Aging 33, 1356–1363 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz J., Niibori Y., Frankland P. W. & Lerch J. P. Rotarod training in mice is associated with changes in brain structure observable with multimodal MRI. Neuroimage 107, 182–189 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter A. J. et al. Functional assessments in mice and rats after focal stroke. Neuropharmacology 39, 806–816 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., et al. Isoflurane postconditioning reduces ischemia-induced nuclear factor-kappaB activation and interleukin 1beta production to provide neuroprotection in rats and mice. Neurobiol Dis 54, 216–224 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blicher J. U. et al. GABA levels are decreased after stroke and GABA changes during rehabilitation correlate with motor improvement. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 29, 278–286 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Cue C., et al. Reducing GABAA alpha5 receptor-mediated inhibition rescues functional and neuromorphological deficits in a mouse model of down syndrome. J Neurosci 33, 3953–3966 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez T. D. & Schallert T. Long-term impairment of behavioral recovery from cortical damage can be produced by short-term GABA-agonist infusion into adjacent cortex. Restor Neurol Neurosci 1, 323–330 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston G. A. Muscimol as an ionotropic GABA receptor agonist. Neurochem Res 39, 1942–1947 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egawa K. et al. Decreased tonic inhibition in cerebellar granule cells causes motor dysfunction in a mouse model of Angelman syndrome. Sci Transl Med 4, 163ra157 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmos-Serrano J. L., Corbin J. G. & Burns M. P. The GABA(A) receptor agonist THIP ameliorates specific behavioral deficits in the mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Dev Neurosci 33, 395–403 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper A. et al. Increased GABA contributes to enhanced control over motor excitability in Tourette syndrome. Curr Biol 24, 2343–2347 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spigelman I. et al. Behavior and physiology of mice lacking the GABAA-receptor delta subunit. Epilepsia 43 Suppl 5, 3–8 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibbens L. M. et al. GABRD encoding a protein for extra- or peri-synaptic GABAA receptors is a susceptibility locus for generalized epilepsies. Hum Mol Genet 13, 1315–1319 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose S. Mutant GABA(A) receptor subunits in genetic (idiopathic) epilepsy. Prog Brain Res 213, 55–85 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulley J. C., Scheffer I. E., Harkin L. A., Berkovic S. F. & Dibbens L. M. Susceptibility genes for complex epilepsy. Hum Mol Genet 14 Spec No. 2, R243–249 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickley S. G. & Mody I. Extrasynaptic GABA(A) receptors: their function in the CNS and implications for disease. Neuron 73, 23–34 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubner C. A. The KCl-cotransporter KCC2 linked to epilepsy. EMBO Rep 15, 732–733 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalek R. M. et al. Attenuated sensitivity to neuroactive steroids in gamma-aminobutyrate type A receptor delta subunit knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96, 12905–12910 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popp A., Jaenisch N., Witte O. W. & Frahm C. Identification of ischemic regions in a rat model of stroke. Plos One 4, e4764 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber M. W. et al. Inter-age variability of bona fide unvaried transcripts Normalization of quantitative PCR data in ischemic stroke. Neurobiol Aging 31, 654–664 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinning A. et al. Synaptic glutamate release is modulated by the Na+ -driven Cl-/HCO3- exchanger Slc4a8. J Neurosci 31, 7300–7311 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holter N. I., Zylla M. M., Zuber N., Bruehl C. & Draguhn A. Tonic GABAergic control of mouse dentate granule cells during postnatal development. Eur J Neurosci 32, 1300–1309 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M. W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29, e45 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. H. et al. Direct protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation regulates the cell surface stability and activity of the potassium chloride cotransporter KCC2. J Biol Chem 282, 29777–29784 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G. & Franklin K. B. J. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (Academic Press, San Diego, 2001). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.