Abstract

Decellularized lung tissue has been recognized as a potential platform to engineer whole lung organs suitable for transplantation or for modeling a variety of lung diseases. However, many technical hurdles remain before this potential may be fully realized. Inability to efficiently re-endothelialize the pulmonary vasculature with a functional endothelium appears to be the primary cause of failure of recellularized lung scaffolds in early transplant studies. Here, we present an optimized approach for enhanced re-endothelialization of decellularized rodent lung scaffolds with rat lung microvascular endothelial cells (ECs). This was achieved by adjusting the posture of the lung to a supine position during cell seeding through the pulmonary artery. The supine position allowed for significantly more homogeneous seeding and better cell retention in the apex regions of all lobes than the traditional upright position, especially in the right upper and left lobes. Additionally, the supine position allowed for greater cell retention within large diameter vessels (proximal 100–5000 μm) than the upright position, with little to no difference in the small diameter distal vessels. EC adhesion in the proximal regions of the pulmonary vasculature in the decellularized lung was dependent on the binding of EC integrins, specifically α1β1, α2β1, and α5β1 integrins to, respectively, collagen type-I, type-IV, and fibronectin in the residual extracellular matrix. Following in vitro maturation of the seeded constructs under perfusion culture, the seeded ECs spread along the vascular wall, leading to a partial reestablishment of endothelial barrier function as inferred from a custom-designed leakage assay. Our results suggest that attention to cellular distribution within the whole organ is of paramount importance for restoring proper vascular function.

Introduction

Given the ever-growing disparity between the increasing demand for transplantable lungs and the limited supply of available donor organs,1 there is an unmet need for alternatives such as bioengineered lungs. Cadaveric lungs, otherwise unsuitable for transplantation, can serve as biologic scaffolds for lung tissue engineering following decellularization and repopulation of both the airway and vascular compartments with adult or progenitor cells.2 Restoration of functional vasculature within such an engineered construct in vitro is critical for the survival of the tissue upon implantation.3 However, re-endothelialization of the decellularized pulmonary vasculature remains a major challenge.4 In this context, we operationally define re-endothelialization as the entire process, from seeding the vascular compartment with endothelial cells (ECs) to the functional maturation of the endothelial monolayer, that is, formation of tight junctions between ECs lining the vascular walls, a step that is critical for restoring endothelial barrier function. Attempts at recellularizing decellularized rodent lung scaffolds that included re-endothelialization of the vasculature, have yielded only partial restoration of the endothelial lining, and in the end failed due to hemorrhage into the airspace upon transplantation.5–8 The most promising work to date reduced vascular resistance and improved endothelial barrier function through the concomitant use of endothelial and perivascular cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), resulting in 75% coverage of the vascular compartment following reseeding of rat and human lungs in the supine position.5

Successful re-endothelialization of the pulmonary vascular tree is hampered by the lack of control over EC seeding (e.g., anatomical position during seeding,9 integrin profile of cells,10 and applying fluid shear stress during culture11), making it difficult to establish an even distribution throughout the lung. Previous studies have demonstrated that the distribution of intravenously injected microspheres larger than 15 μm, similar to the size of ECs, in the pulmonary vasculature varies according to anatomical position of the rodent during injection (e.g., upright: the lungs hanging by the trachea vs. supine: the lungs laying on their back).9 Endothelial progenitor cells, which express the α5β1 integrin, efficiently adhere to fibronectin remaining on the luminal walls of denuded large vessels in vivo.10 A similar process might govern the adhesion of ECs to fibronectin that is found on the walls of decellularized pulmonary vasculature.12 Finally, fluid shear stress maintains endothelial phenotype in vivo, and regulates endothelial permeability in vitro: exposure to fluid shear stress in the range of 2–50 dyn/cm2 leads to the maturation of endothelial monolayer, as inferred from an increase in its barrier function by 15%.11 This approach has also been applied to ECs cultured in the vasculature of rat and human decellularized lung scaffold (DLS).5

Current ex vivo lung decellularization and recellularization approaches reproducibly create acellular whole lung scaffolds through tracheal and pulmonary artery perfusion with detergents that not only retain the basic anatomy and key extracellular matrix (ECM) components of the intact lung,7,8,13 but also conserve the branching geometry and patency of its vascular tree system.14 In this study, we used acellular rat lung scaffolds in two different postures (upright and supine) to study how anatomical position modulates re-endothelialization by characterizing the resulting EC distribution throughout the vascular compartment. Our results indicate improved re-endothelialization of the proximal regions of the pulmonary vasculature, when the decellularized lung was seeded in the supine position, as compared to re-seeding in the upright position. Adhesion to the DLS depended on the integrin expression of the ECs used for recellularization as inferred from a three-dimensional (3D) adhesion assay demonstrating that integrins α1β1, α2β1, and α5β1 are essential for adhesion within the macrovasculature. Finally, postseeding perfusion culture enhanced the maturation of the endothelium as inferred from an improvement of its barrier function.

Materials and Methods

DLS preparation

All animal procedures were carried out according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Male Sprague Dawley rats (260–280 g; Charles River, Malvern, PA) were euthanized with CO2. After exsanguination and insertion of catheters into the pulmonary artery (PAC), left ventricle (LVC), and trachea (TC), hearts and lungs were removed en bloc. The lungs were decellularized using 0.1% Triton X-100 and 2% sodium deoxycholate according to a published protocol.14

Histology

The lungs were inflation-fixed15 and the lobes subsequently cut horizontally from apex to base into regions roughly 5 mm in thickness (Fig. 4). These pieces were paraffin-embedded as previously described.16 Chemical stains included hematoxylin and eosin (routine histology), Masson's trichrome (collagen), Verhoeff van Gieson (elastin), 2-(4-amidinophenyl)-1H-indole-6-carboxamidine (DAPI, nuclei), and AF546 phalloidin (DAPI and Phalloidin from Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Stained sections were visualized in an FSX100 inverted microscope and imaged with the FSX-BSW software (Olympus, Center Valley, PA).

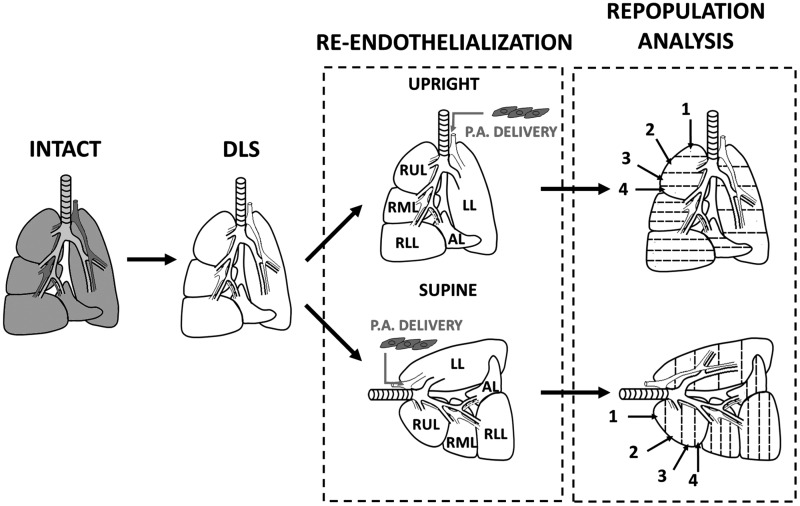

FIG. 4.

Schematic for decellularization, recellularization, and analysis. The decellularized rat lungs were seeded in two different anatomical positions so as to discover the impact of position on the distribution of endothelial cells (ECs) via the pulmonary artery. Numbering represents sections of lobes from apex to base. DLS, decellularized lung scaffold; INTACT, lungs before decellularization; P.A. DELIVERY, ECs seeded into DLS via the pulmonary artery; REPOPULATION ANALYSIS, regions of lobes are processed for histology, sectioned, stained, and imaged as described in the M&M; SUPINE, lung seeded while lying in supine position; UPRIGHT, lung seeded while held upright suspended by the trachea.

Scanning electron microscopy

For scanning electron microscopy, lungs were fixed in a modification of Karnovsky's fixative, that is, 2.5% glutaraldehyde with 4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by inflation fixation.15 Fixed lungs were sectioned into ∼5 mm thick regions, as above, dehydrated, and dried in a Critical Point Drying Apparatus (CPD 7501; SPI supplies, West Chester, PA). Samples were then coated with Pt/Pd for 40 s at a gas pressure of 0.025 mbar using a Cressington sputter coater 208 (Watford, England) with current set at 40 mA, and imaged on a XL-30 Field-Emission Environmental Scanning Electron Microscope (ESEM-FEG; FEI, Hillsboro, OR), as previously described by Senel Ayaz et al.17

Contrast agent perfusion

Intact lungs and DLS were perfused manually with an X-ray contrast agent, Omnipaque™ (iohexol, NDC 0407-1413-68; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) in 200 μL increments using a tuberculin syringe. The lungs were imaged with an IVIS Lumina XR in vivo imaging system (Perkin Elmer, Inc., Waltham, MA) set to X-ray mode. The IVIS Lumina was operated at 28 V/100 mA; images were acquired using Living Image Software version 4.3.1 (from Perkin Elmer). The vascular tree of the decellularized rat lungs was also visualized by perfusing the DLS through the pulmonary artery with a solution containing 0.06% low viscosity alginic acid sodium salt and 0.1% alcian blue 8GX (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The cannulated lung was first perfused via the pulmonary artery with PBS at 3 mL/min for 10 min to remove any air bubbles using a syringe pump, and then with the alcian blue solution at 1 mL/min.

RLMVEC culture

Pooled primary rat lung microvessel ECs (RLMVEC) isolated from adult male Sprague Dawley rats (VEC Technologies, Rensselaer, NY) were kindly donated by Dr. Laurie Kilpatrick, Temple University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA. The endothelial phenotype of the cells had been ascertained by the vendor by acetylated-low density lipoprotein uptake and expression of Von Willebrand factor. The cells were maintained in MCDB-131 (Corning, Manassas, VA) media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1% l-glutamine (Corning). RLMVEC were routinely split at a ratio of 1:8 once they reached ∼80% confluence. All cells used for our studies were of a passage number no greater than 12.

Immunocytochemistry

RLMVEC were cultured on gelatin-coated plastic eight-well chamber slides (Sigma-Aldrich) until 48 h postconfluence, and then fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 20 min at 25°C. Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 at 25°C for 15 min, and then blocked with 10% goat serum for 1 h at 25°C. Primary antibodies—1:20 rabbit anit-CD31 (ab28364; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and 1:50 rabbit anti-ZO-1 (40-2300; Life Technologies)—were applied at 4°C for 18 h. Secondary antibody or lectin was then applied—1:1000 goat anti-rabbit AF568 (ab175471; Abcam) in 1% goat serum; 1:100 isolectin GS-IB4 (AF568, I21412; Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA)—for 1 h at 25°C. DAPI was applied (1 μg/mL in 1% goat serum) for 30 min at 25°C. Slides were mounted with Fluoromount-G (e-Bioscience, San Diego, CA) and imaged as above.

RLMVEC seeding of DLSs

Cells were harvested at ∼80% confluence and resuspended at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL in 10 mL of MCDB-131 media. The tracheal catheter was capped, and the lungs were positioned for seeding either in an upright position, that is, by hanging from the trachea (Supplementary Fig. S1A, B; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec),7,8 or placed in a supine position (Supplementary Fig. S1C, D).18 Lungs were first primed for 10 min with HBSS containing calcium and magnesium warmed to 37°C in a water bath at 3 mL/min with a syringe pump (model: Fusion 100; Chemyx, Inc., Stafford, TX). The cell suspension was then delivered continuously into the DLS via the pulmonary artery at a flow rate of 1 mL/min.

Cell counting method for global cell distribution

Following cell delivery, lungs were incubated at 37°C for 1 h, washed via the pulmonary artery with 60 mL warm HBSS at 3 mL/min, and finally processed for imaging of DAPI as described above. A custom ImageJ script was used to determine the cell counts in each individual tissue section (Supplementary Table ST1). Each tissue section (one section per region) represents a different region within a given lobe (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3).16 To compare the distribution from lobe to lobe, cell counts from all regions of a particular lobe were averaged and normalized to the dry weight of the respective lobe (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. S4). To quantify the distribution of RLMVECs within various size vessels, a similar cell counting method was applied to individually traced vessels, whereby the cell count within the vessel was normalized to the perimeter of that vessel (Fig. 6).

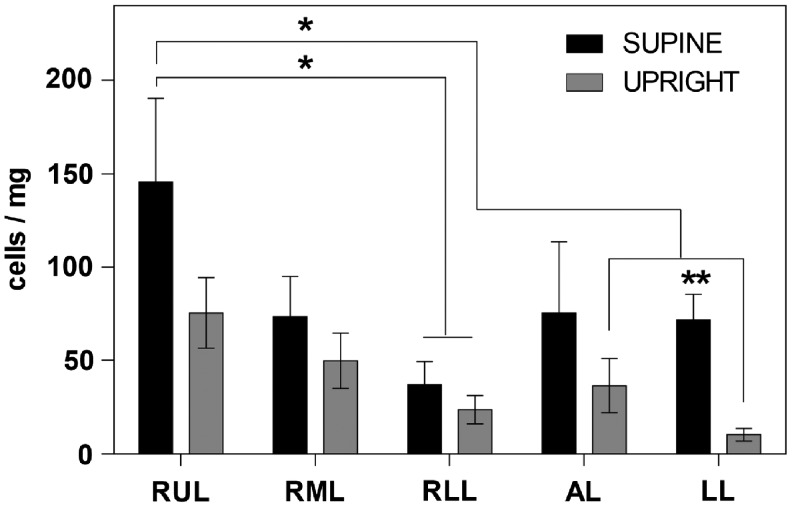

FIG. 5.

Distribution of ECs across the whole decellularized lung 1 h after seeding. The total cell distribution was based on estimates within each lobe (for details see M&M and text), and indicates that the supine position allowed greater and more even distribution of ECs seeded through the pulmonary artery. For each individual lobe, the average of the cell counts within each region was normalized to the dry weight of that lobe (determined from three independently seeded lungs). *The supine RUL cell count (cells/mg) is significantly higher than the one for the RLL of the supine lung; the RLL, AL, and LL of the upright lung according to multiple comparisons from a two-way ANOVA (n = 3, α < 0.05). **In the LL, the supine cell count (cells/mg) is significantly higher than the upright according to t-tests (n = 3, p = 0.0001).

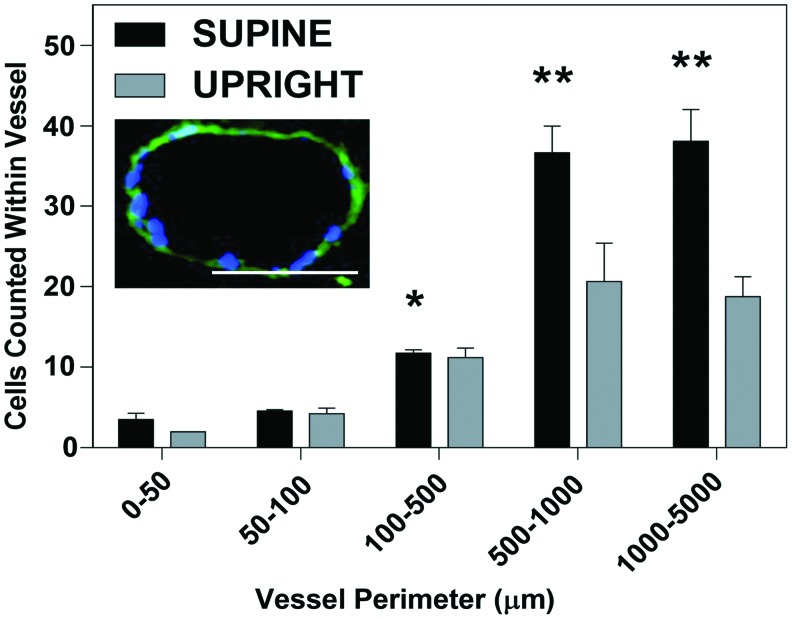

FIG. 6.

ECs counts within vessels of various sizes 1 h after seeding. Seeding ECs in the supine position will allow greater retention in the macrovasculature compared with seeding in the upright position. *Statistically significant, higher than in vessels of perimeter 50–100 μm in the supine position by two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons (α < 0.05); **statistically significant, higher than in vessels of perimeter 0–50, 50–100, and 100–500 μm in the supine position and 50–100 and 100–500 μm in the upright position by two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons (α < 0.05). Insert: Representative image of medium-sized vessel used for determining cell counts. This particular vessel has a perimeter of 410.02 μm with 18 nuclei counted within. Scale bar = 100 μm, magnification = 20×. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

2D and 3D cell adhesion assay

To determine the integrin-dependence of RLMVEC attachment, we employed a previously published two-dimensional (2D) adhesion assay, in which the cells adhere to an array of ECM proteins or to integrin subunit-specific antibodies immobilized in individual wells of a 96-well plate.16 The ECM proteins included the following: rat tail collagen-I (from Becton Dickinson [BD], Franklin Lakes, NJ), recombinant human plasma fibronectin (Millipore, Billerica, MA), mouse collagen-IV (3410-010-01; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), human recombinant laminin-521 (BioLamina, Sundbyberg, Sweden), and Vitronectin XF (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC). The integrin-subunit-specific antibodies (from BD) recognized the following: α5 (Cat No. 553350), α1 (Cat No. 555001), α2 (Cat No. 559987), or β1 (Cat No. 555003). To test the specificity of integrin binding to individual ECM proteins, adhesion assays were performed in the presence of select disintegrins, that is, integrin inhibitors with the following specificities19: VLO4-α5β1 inhibitor, VP12-α2β1 inhibitor, obtustatin-α1β1 inhibitor, and VLO5-α4β1 inhibitor. For these studies, the cells were incubated with the various disintegrins, all at working concentration of 50 μg/mL, for 10 min before seeding onto the immobilized proteins. The same concentration of disintegrins was present in the incubation medium during the subsequent adhesion period (30 min).

To test the integrin-specificity of EC adhesion in the vascular compartment of the DLS, we developed a novel 3D adhesion assay, in which the whole perfused DLS was maintained in the supine position for all manipulations.20 First, the lungs were washed with HBSS by perfusion through the PAC at 3 mL/min for 10 min. Nonspecific binding was then blocked by perfusion of 1% FBS for 1 h through the PAC at the same flow rate. RLMVEC (106 cells/mL) were treated with integrin inhibitors (VLO4, VP-12, and obtustatin, all 50 μg/mL) for 10 min before seeding and perfused in the continued presence of integrin inhibitors into the lung via the PAC at a rate of 1 mL/min for 10 min. The cells were subsequently allowed to adhere for 30 min at 37°C. The re-endothelialized organs were then washed through the PAC with 60 mL of HBSS at a flow rate of 3 mL/min and immediately fixed for later imaging as described above.

Perfusion culture

Following static reseeding, the lungs were perfused with warmed media using a peristaltic pump (Model No. 54655; Rainin Rabbit Peristaltic Pump, Oakland, CA). The lungs were placed in the supine position in a 100 mm petri dish, and the media was circulated from the petri dish to the PAC at a rate of 3 mL/min. Perfusion was continued for 48 h and 1 week, at which time the lungs were fixed and processed as described above.

Confocal microscopy

Lungs were fixed and paraffin-embedded as described above. Sections (200 μm thick) were stained with DAPI and phalloidin, and mounted with Vectashield. The cell distribution in these thick tissue sections was examined in a laser scanning confocal microscope (Fluoview FV1200; Olympus), and images acquired with the Olympus FV10-ASW version 4.0b software. Images were taken at 20× magnification.

FITC-dextran barrier function assay

Lungs (intact, decellularized, and recellularized) were prepared for perfusion as shown in the diagram in Supplementary Fig. S5 and inflated with air through the trachea, which was then capped to prevent deflation of the lungs. Subsequently, the lungs were perfused through the pulmonary artery with PBS at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Up to 15 fractions (∼1 mL each) of perfusate were collected sequentially from the left ventricle catheter. After the first three fractions of PBS were collected, a bolus (2 mL) of 1 mg/mL FITC-Dextran (150 kDa) was perfused at 1 mL/min. Upon completion of the bolus injection, PBS perfusion was continued as was the collection of ∼1 mL fractions. The fluorescence in the fractions was quantified using a plate reader (FLX800, λEx = 485 nm/λEm = 528 nm; Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT), and correlated to a standard curve to calculate the concentration of FITC-Dextran in the perfusate.

Statistics

All experiments were repeated independently at least three times, with multiple measurements for each data point. The results were analyzed statistically using GraphPad Prism v6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). When evaluating the distribution of cells normalized either per milligram of tissue, or per μm vessel perimeter, comparing upright versus supine position of the various lobes, the results were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Turkey's multiple comparisons test, with α < 0.05 for statistical significance. Additionally, total cell numbers from the upright versus supine positions of individual lobes were analyzed by multiple t-tests with multiple comparisons corrected by the Sidak-Bonferroni method, with p < 0.05 for statistical significance. Data are presented as mean values ± the standard error of the mean. Cell adhesion assays were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Turkey's multiple comparison tests.

Results

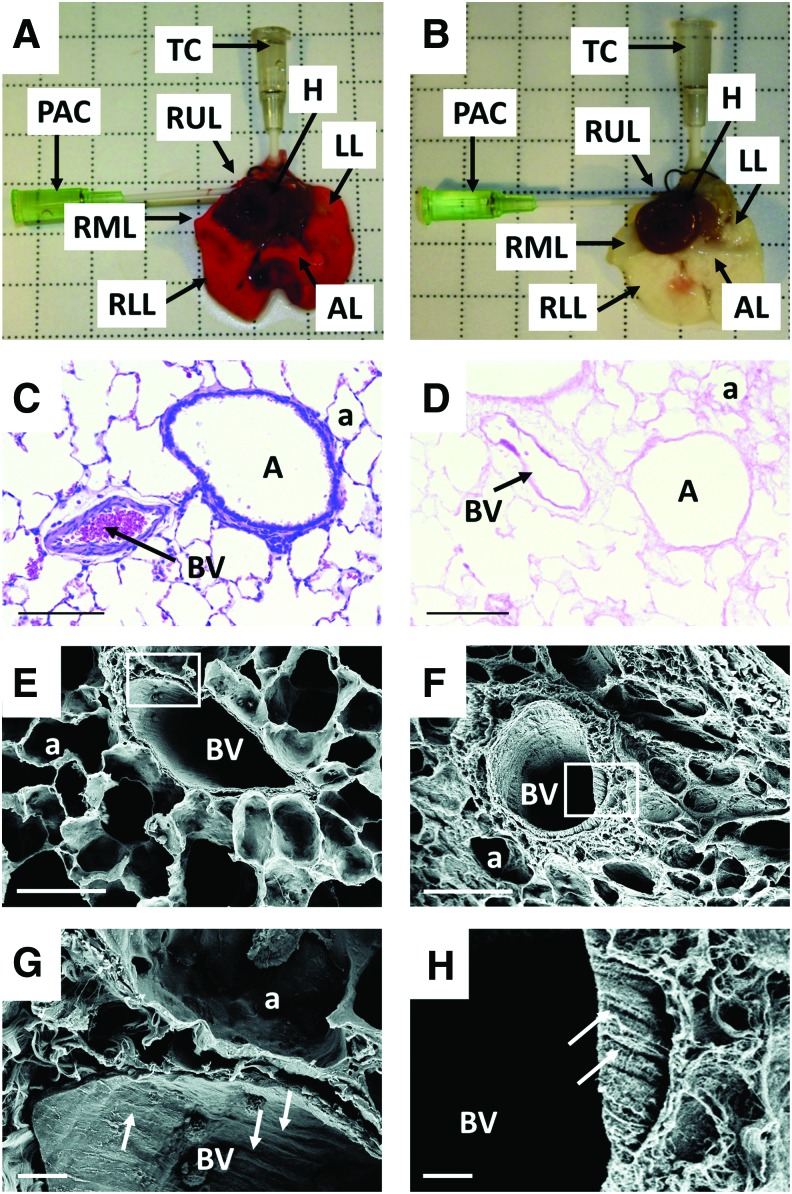

Decellularization

Decellularization of whole rat lungs was carried out essentially according to the protocol developed by Girard et al.21 As previously described by Price et al.13 upon decellularization the color of the organ turned from red to opaque/white (Fig. 1A, B, respectively). Successful decellularization was also confirmed indirectly by the fact that the dry weights of the individual lobes of the lung following decellularization were significantly lower than those of their intact counterparts (Supplementary Fig. S4). The morphology of the intact and decellularized lungs was assessed by routine hematoxylin and eosin staining, and showed general maintenance of the tissue's architecture (Fig. 1C, D respectively). The presence/absence of cells was also demonstrated by staining with DAPI (Supplementary Fig. S6A, B, respectively). By scanning electron microscopy, the patent blood vessels of intact lungs were identifiable by aligned endothelium in the direction of blood flow (region of interest, Fig. 1E, G), following decellularization, the remaining ECM of the blood vessels showed a similarly aligned orientation (region of interest, Fig. 1F, H).

FIG. 1.

Decellularization of rat lungs. The gentle dissection and decellularization process employed here resulted in a matrix that highly resembled that of the intact lung. (A) Native heart–lung complex immediately following dissection (arrows identify catheters and lobes of intact lung). (B) Decellularized lung following the completion of the decellularization procedure, for details on the decellularization protocol, see text (arrows identify catheters and lobes of decellularized lung scaffold). (C) Intact lungs were processed for histology immediately following dissection, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, scale bar = 100 μm, original magnification = 20×. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin stain of the decellularized lung (arrows identify lumen of blood vessels) scale bars as in (C). (E) Scanning electron micrograph of native lung, scale bar = 100 μm, original magnification = 2000×. (F) Scanning electron micrograph of decellularized lung, scale bar as in (E). (G) Scanning electron micrograph of native lung from region of interest in (E) (arrows identify aligned endothelial cells), scale bar = 10 μm, original magnification = 10,000×; (H) Scanning electron micrograph of decellularized lung from region of interest in (F) (arrows identify alligned ECM in vessel wall), scale bar as in (G). A, airway; a, alveolus; AL, accessory lobe; BV, blood vessel; H, heart; LL, left lobe; PAC, pulmonary artery catheter; RLL, right lower lobe; RML, right middle lobe; RUL, right upper lobe; TC, tracheal catheter. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

Vascular perfusion of DLS

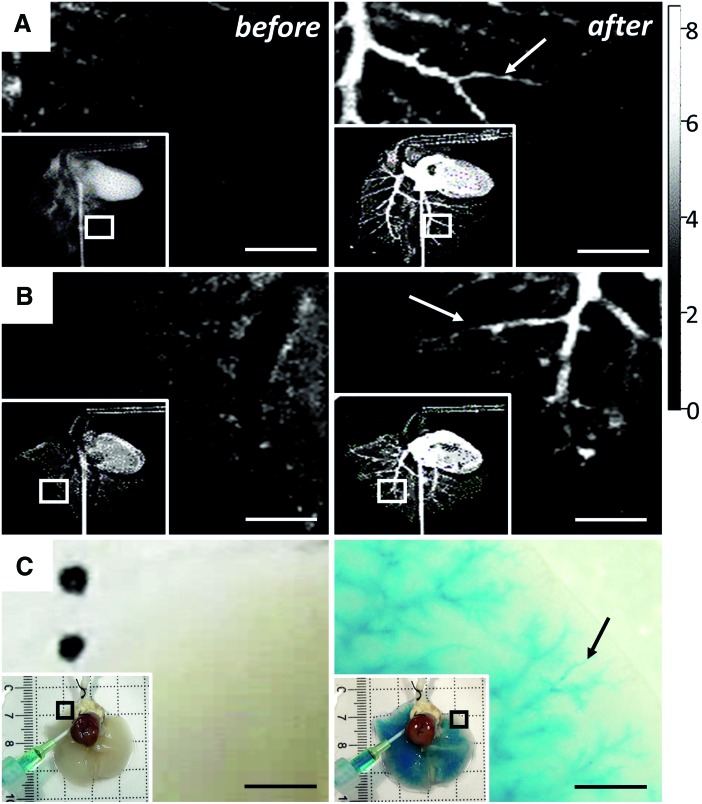

Perfusion with a commercial X-ray contrast agent was restricted to the vasculature in both intact lungs (Fig. 2A) and DLS (Fig. 2B), where no contrast agent can be seen before perfusion (Fig. 2 left column) and can clearly be seen following perfusion (Fig. 2 right column). Introduced via the heart, the contrast agent distributed through all lobes of the intact and decellularized organ (inserts of Fig. 2A, B, respectively) allowing for identification of perfusion through small diameter blood vessels down to 0.25 mm in diameter (Fig. 2A, B, right panel, arrows). Perfusion with an alcian blue solution mimicking the viscosity of blood (3–4 centiPoise22) allowed for identification of the intact microvasculature (Fig. 2C). Like with the X-ray contrast agent, before perfusion no color can be seen within the tissue (Fig. 2C, left column); following alcian blue perfusion the vasculature of the DLS was identifiable down to a diameter of 30 μm (Fig. 2C, right column) colored solution distributed evenly throughout the lung (Fig. 2C, inserts).

FIG. 2.

Assessment of perfusion through decellularized pulmonary vasculature. The gentle decellularization process employed here resulted in a vascular compartment that largely contained flow of solute, but inevitably showed some leakage in the microvasculature. (A) Left panel: X-ray image of native lung before contrast agent perfusion (region of interest shown in insert), right panel: native lung following perfusion of 1 mL of contrast agent shows restriction of solution within vascular compartment (scale bars = 5 mm) (arrow identifies X-Ray contrast agent within intact microvasculature). (B) Same representation before and after contrast agent perfusion of decellularized lung shows that solution is largely retained within vascular compartment, but shows some leakage in the microvasculature (scale bars = 5 mm) (arrow indicates X-Ray contrast agent within microvasculature); gray scale: X-ray absorption; min = 0, max = 8.436. Values are ×1000. (C) Left panel: Decellularized lung before Alcian blue perfusion (region of interest shown in insert), right panel: decellularized lung following perfusion of 1 mL of Alcian blue solution where Alcian blue solution can be seen leaking from microvasculature (region of interest shown in insert), scale bars = 1 mm (arrow identifies dye within microvasculature). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

Blood vessel associated ECM protein content in DLS

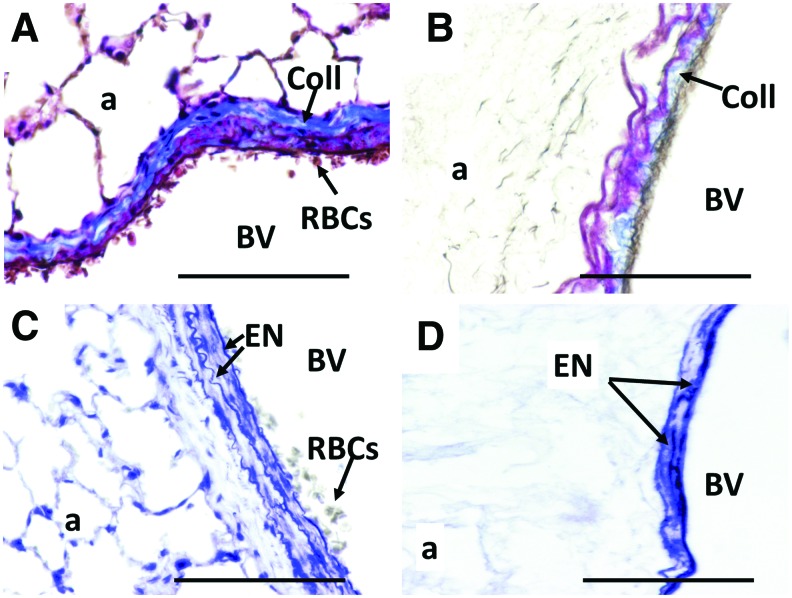

Staining intact lungs with Masson's trichrome demonstrated the presence of dense collagen fibers (Coll with arrow, Fig. 3A) in the walls of intact large blood vessels. Collagen fibers in the walls of blood vessels were also present following decellularization, but in reduced amounts, as inferred from the reduced intensity and loss of continuity of the staining using the exact same staining protocol as for intact lung (Fig. 3B). Intact lungs showed the presence of wavy internal and external elastic lamina surrounding the tunica intima and the tunica media, respectively (Elastin [EN] with arrows, Fig. 3C). Similar multiple EN layers were visible following decellularization, but their wavy appearance and contiguity were lost (Fig. 3D).

FIG. 3.

Visualization of ECM proteins in the vascular wall before and after decellularization. Though considered gentle, due to the maintenance of the morphology of the lung, the decellularization process employed here showed that the vascular-specific ECM proteins may be damaged though present in the tissue. (A) Masson's trichrome stain of native lung, immediately following dissection. (B) Masson's trichrome stain of decellularized lung, with staining of collagen (blue) in the vessel walls seen as less intense and less contiguous than in the intact lung. (C) Verhoeff-van Gieson stain of native lung, immediately following dissection. (D) Verhoeff-van Gieson stain of decellularized lung, with elastin fibers (black) seen as more fragmented, with a loss of waviness compared with intact lung. All scale bars = 100 μm, and all original magnifications = 40×. Arrows are used to identify the following: Coll, collagens; ECM, extracellular matrix; EN, elastin; RBCs, red blood cells. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

RLMVEC distribution across all lobes of DLS

The RLMVEC population used was characterized as CD-31+, ZO-1+ (Supplementary Fig. S7), and isolectin GS-IB4+ (data not shown) and maintained this phenotype over time in culture within the DLS (data not shown). DLS were seeded with RLMVEC in either the upright or supine position (Supplementary Fig. S1). After allowing the cells to adhere for 1 h under static conditions, the tissue was fixed and the lobes divided into roughly equally thick (∼5 mm) horizontal regions, a single 5 μm slice per region, taken consistently ∼50 μm into the region, was used to quantify the number of cells in each section (Fig. 4, S3). The averages of the cell counts of all regions of each individual lobe (from n = 3 animals) were normalized to the average dry weight of those decellularized lobes (Supplementary Fig. S4). In general, the supine seeded lung vasculature retained on average more cells than the upright one; however, based on a two-way ANOVA, only the average of the cells in the supine-right upper lobe (RUL) was significantly higher than that in the upright-RUL by roughly twofold (n = 3; α < 0.05). Additionally, based on multiple t-tests, the average of the cells in the supine-left lobe (LL) was significantly higher than that in the upright-LL by roughly sixfold (n = 3; p < 0.01) (Fig. 5).

RLMVEC distribution within individual lobes of DLS

In addition to comparing cell distribution between lobes, we also quantified cell distribution within individual lobes. We found a trend of increased EC numbers in the apex-regions (i.e., regions 1–3) of all lobes except for the accessory lobe (AL) when seeding in the supine position compared to the upright position (Supplementary Fig. S2A). The most significant difference was found in region number 1 of the LL, where seeding in the supine position yielded 10 times more ECs than the upright (Supplementary Fig. S2E; n = 3, p < 0.02). Interestingly, region 4 of the supine-RUL, right middle lobe (RML) and right lower lobe (RLL) had ∼10 times less cells than that of their corresponding regions in the upright-RUL, RML, RLL, and AL (Supplementary Fig. S2A–D; n = 3 for all, p < 0.02 for all except AL where p = 0.15).

RLMVEC distribution according to vessel perimeter range within DLS

Distribution of RLMVEC across various size vessels was quantified for both the upright and the supine seeding methods by counting DAPI-stained nuclei in combination with imaging the autofluorescence of the perivascular ECM. Cells counts within the various size vessels were normalized to the vessel perimeter (Fig. 6). The insert in Figure 6 paradigmatically shows a vessel of 410 μm in diameter containing 18 DAPI-stained cells. Seeding in the supine position allowed approximately twice the number of cells to adhere to the larger vessels ranging from 500 to 5000 μm than in the upright position (Fig. 6).

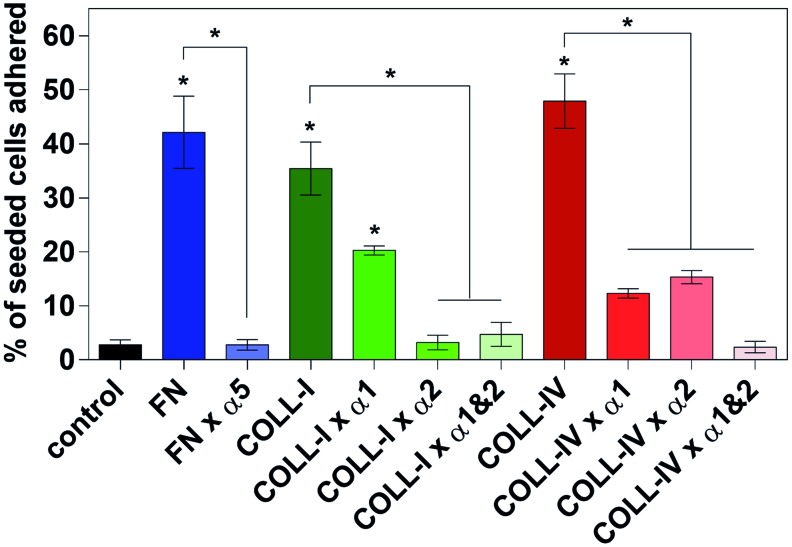

Integrin-specific adhesion of the RLMVEC to vascular compartment of DLS

In the 2D model, adhesion of RLMVEC to immobilized ECM proteins commonly found in the decellularized lung, that is, fibronectin, collagen-I, and collagen-IV, was statistically identical and ∼16, 13, and 18 times greater than to the control surface of FBS-coated tissue culture plastic, respectively (Fig. 7; n = 6, α = 0.05 for all). Similarly, RLMVEC adhesion to immobilized monoclonal antibodies against integrins α5, α1, α2, and β1 was ∼10 times greater than to the control surface (data not shown; n = 6, α = 0.05 for all). In the presence of the α5β1 inhibitor (VLO4 disintegrin; 50 μg/mL), EC adhesion to fibronectin was decreased to the level of control. In the presence of the α1β1 antagonist obtustatin (50 μg/mL), RLMVEC adhesion to collagen-I decreased by ∼43% and that to collagen-IV by ∼74%; by contrast, in the presence of an α2β1 inhibitor (VP12 disintegrin; 50 μg/mL), EC adhesion to collagen-I was decreased to the level of control, and to collagen-IV by ∼68%. When the α1β1 and α2β1 inhibitors were combined the adhesion to these two collagens was decreased back to level of control (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Two-dimensional adhesion assay of rat pulmonary ECs to immobilized ECM proteins RLMVEC adhere to FN, COLL-I, and collagen type-IV significantly more than serum-coated wells (control), and are insignificant compared to one another. RLMVEC adhesion to ECM proteins in the presence of integrin antagonists showed that the α1 antagonist leads to a partial inhibition of adhesion to COLL-I and COLL-IV; 43% and 74% decrease, respectively. The α2 antagonist abolished adhesion to COLL-I, but partially inhibited adhesion to COLL-IV (68% decrease). The combination of the α1 and α2 antagonists abolished adhesion to COLL-I and IV. All groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons (n = 6, α < 0.05) * indicates significance over control, or between groups covered with a reference bar. COLL-I, collagen type-I; FN, fibronectin; RLMVEC, rat lung microvessel ECs. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

In the 3D model (seeding of the vascular tree in DLS with ECs), pretreating the cells with disintegrins that specifically antagonize the binding to α5β1, α2β1, and α1β1 integrins, completely prevented RLMVEC adhesion to the macrovasculature of the DLS. Instead, the seeded cells were found only within the smallest vessels (capillaries) ranging from 10 to 21.5 μm (average 13.4 ± 4.6 μm) in diameter (data not shown), presumably clogging the lumen of these capillaries.

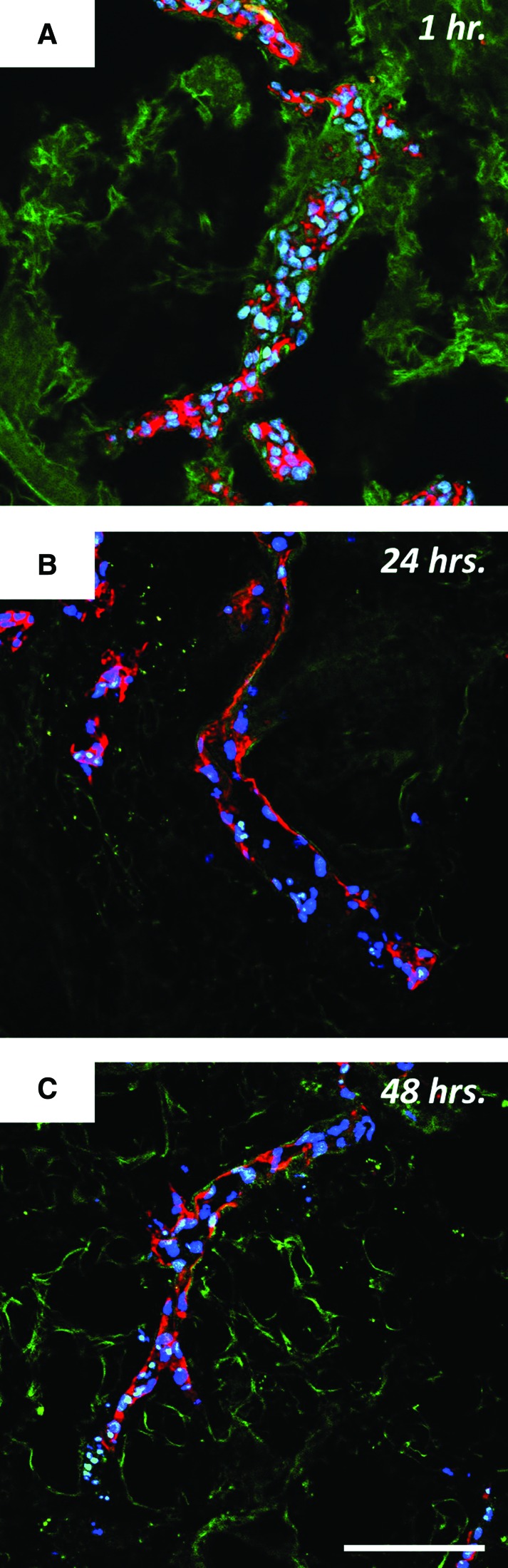

Spreading of the endothelium within DLS

With more cells present in the proximal vessels of the lobes, the supine position was deemed most appropriate for organ culture studies. After 1 h in the DLS under static conditions without perfusion, cells were found adhering to the walls of larger vessels, but also clogging the lumen of some smaller vessels (Fig. 8A). Staining for F-actin showed no spreading of the cells attached to the vessel walls immediately following seeding (Fig. 8A). Following perfusion culture for 24 h F-actin staining showed apparent cell spreading along the vessel wall (Fig. 8B). Moreover, no RLMVEC aggregates were found in the lumen of the larger vessels. Cell spreading was sustained up to 48 h of perfusion culture (Fig. 8C).

FIG. 8.

RLMVEC within the vasculature of DLS at various points in perfusion culture. ECs adhere and spread along the vessel wall when seeded under low flow conditions and exposed to perfusion with low-levels of shear stress. F-actin is stained in red, nuclei are stained in blue, and the DLS is autofluorescent in green. (A) RLMVEC within decellularized lung 1 h postseeding under static conditions show little or no adhesion with a large amount of clogging in the lumen of the vessel; (B) Following 24 h of perfusion culture at 3 mL/min the cells are clearly adhered and spread leaving a hollow lumen; (C) Following 48 h of perfusion culture at 3 mL/min this hollow lumen is maintained and the degree of spreading is similar to that seen after 24 h of perfusion culture. Scale bars = 100 μm, original magnification = 20×. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

Increased barrier function following maturation of RLMVEC within vascular compartment of DL6S

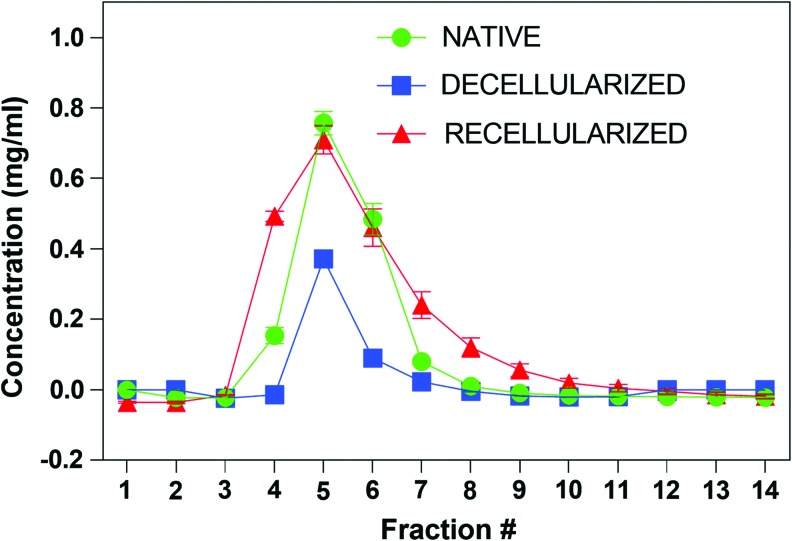

To measure the barrier function of intact, decellularized, and recellularized rat lungs we developed a semi-quantitative FITC-Dextran perfusion assay based on a previously published permeability assay of RLMVEC grown in 2D.23 For all lungs the first appearance of FITC-Dextran was found in the fourth fraction of the perfusate, while the peak concentration was observed in the fifth fraction (Fig. 9). No FITC-Dextran eluted in either the intact and decellularized lungs after the ninth fraction, or in the recellularized lungs after the 12th fraction. The intact lungs had a consistent peak concentration of 0.75 ± 0.03 mg/mL FITC-Dextran, while that of the decellularized lungs was 0.37 ± 0.004 mg/mL. Following re-endothelialization and culture under flow for 1 week, the peak concentration increased to 0.71 ± 0.04 mg/mL (Fig. 9), indicating maturation of the endothelium and restoration of the permeability barrier function of the recellularized vascular compartment equivalent to ∼95% of the value found for intact lung.

FIG. 9.

Partial restoration of vascular permeability barrier following maturation of RLMVEC with DLS. Lungs, native, decellularized, and recellularized, were maintained under perfusion culture. Following administration of a 2 mL bolus of 150 kDa FITC-Dextran (1 mg/mL), the fluorescence of individual 1 mL fractions of the effluent out of the left ventricle was measured in a fluorescent plate reader. Decellularization significantly decreases the amount of recovered dye in the effluent due to leakage into the parenchyma, while re-endothelialization essentially restores the barrier function. The concentration of FTIC-Dextran in each fraction was determined from a standard curve of 150 kDa FITC-Dextran. Green, native lung; blue, decellularized lung; red, recellularized lung. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

Discussion

The main goal of this study was to rationalize and optimize the re-endothelialization process that would lead from seeded ECs to a functional endothelium. Our results suggest that (1) the distribution of ECs within the vascular compartment of the decellularized lung is modulated by the anatomical position of the organ at the time of cell seeding, (2) the initial adhesion of the seeded cells is dependent on their integrin repertoire, and (3) that perfusion culture of re-endothelialized organ is a critical first step to reestablishing barrier function of the engineered vasculature.

Gentle decellularization preserves the pulmonary vascular compartment

In line with previous reports,5,24,25 our work demonstrates that following gentle decellularization by detergent perfusion26 the vascular compartment of the DLS remains largely intact, and capable of supporting perfusion of the entire organ, although some leakage of perfused proteins through the parenchyma was observed (Fig. 2). The ECM of the vessel wall was partially left in place (Fig. 1F), however, similar to prior reports,27 the amounts of individual ECM proteins were reduced and some glycoproteins, such as laminin, are damaged (Stabler and Lelkes, unpublished observation). In terms of physical damage to the ECM, recent work by Ren et al. utilizing 0.2 and 0.02 μm diameter fluorescent microspheres, indicated that if the perfusion pressure does not exceed 20 mmHg, these microspheres (which are ca. 10–100 times smaller in diameter than a cell) are restricted to the vascular compartment.5 In our work, maintenance of vascular wall structure and function following decellularization is likely due to the use of more gentle detergents (TX100 and SDC) employed in an intermittent fashion,25 versus continual perfusion with harsher detergents, such as SDS or CHAPS.4

EC distribution follows physiologic blood flow

Physiologic blood flow within the intact lungs is heterogeneous across the individual lobes. In the intact rat lungs, the left lung makes up ∼40% of the total lung average mass (Supplementary Fig. S4), and receives ∼44% of the mean total lung blood flow, while the right lung, comprising ∼60% of the average lung mass, receives ∼56% of the mean total blood flow when in the supine position.9 The RUL of the intact rat lungs receives the majority of the right pulmonary artery blood flow (33%) compared with the RML (26%), RLL (13%), and AL (28%).28 This finding may explain our observation that the RUL receives the majority of the seeded ECs instilled in a supine position (Fig. 5). The observation of the left lung in the upright position having the least amount of cells could likely be due to a change in pulmonary artery position. In the upright position (Supplementary Fig. S1A, B), the PAC being oriented horizontally, the tension of the lung may yield a crimping of the left pulmonary artery and hence result in less cells entering the LL compared with the right lung. Since the reseeded lungs in the upright position had significantly more cells in the most basal region of their lobes, we suggest that gravity plays a role in the fluid distribution in accordance with the 3D branching pattern of the pulmonary circulation, and could have implications for cell seeding in conventional bioreactors that keep the lungs hanging by the trachea.7,8,13 Recent work delivering differentiated iPSCs into the pulmonary vasculature yielded more homogeneous distribution of cells throughout the DLS that was held in the supine position.5 While in our studies of EC seeding in the supine position (and in that of Ren et al.5) the DLS were not ventilated during the seeding process, we speculate that cell distribution within the vascular compartment could be further enhanced by inclusion of physiological mechanical stimuli, such as cyclic mechanical stretching in the wake of ventilation. For example, the seeding procedure of Petersen et al. included a 1 mL/min wet ventilation and led to partial gas transfer in the transplanted recellularized lungs.7

Enhanced initial adhesion in supine position

When ECs were seeded into the vascular compartment of DLS lying in the supine position their ability to adhere to the large vessel walls was significantly enhanced (Fig. 6). We hypothesize that this difference is likely due to the enhanced resident time of the cell suspension within the pulmonary macrovasculature due to the interaction of ECs integrins with DLS ECM proteins. In the upright position, the cell suspension delivered through the pulmonary artery is not allowed as much time to remain in the macrovasculature as in the supine position. We speculate that even though the flow rate during seeding in the two positions is equal (1 mL/min), the force of gravity in the upright position might increase the local flow rate and thus impede initial cell adhesion. In other words, in an upright DLS the seeded cells will tend to “fall down” the larger sized conduits.

Endothelial adhesion to the decellularized vasculature is mediated via integrins

We have previously shown that understanding the integrin profile of the cells used for reseeding is critical for optimizing the seeding procedure and for understanding where/how they will adhere to a scaffold.16 The RLMVEC used in our study express a wide array of functional integrins, in particular those that bind fibronectin (FN) and collagens (Fig. 7). However, even though FN and collagens I and IV are present following decellularization, although at reduced amounts, they are left fragmented and/or otherwise damaged,29 for example, as inferred from the loss of ENs wavy-structure following decellularization (Fig. 3D), raising some doubt whether cell adhesion may or may not be integrin-mediated. In particular, residual FN and laminin in DLS have been shown to be largely fragmented, as seen by western blot analysis of nonhuman primate decellularized lungs.12 Nevertheless, our data demonstrate some functionality of the residual ECM proteins in the subendothelium. Adhesion of RLMVEC to the decellularized vascular walls was completely abolished following exposure to a cocktail of the disintegrin antagonists of the α5β1, α1β1, and α2β1 integrins mentioned above (50 μg/mL each). Taken together these data suggest that the residual ECM in the decellularized vascular compartment contains functional fragments of FN, COLL-I, and COLL-IV, which is expected, given the composition of the ECM of the intact vasculature30 and that these fragments are capable of engaging EC integrins. We speculate that EC adhesion might be further enhanced by functionalizing/coating the decellularized vascular wall with intact ECM proteins, such as laminin and fibronectin, as we have done before,16 or by stimulating the ECs to upregulate the integrins against these proteins, for example, similar to the upregulation of α5β1 on circulating endothelial progenitor cells following Simvastatin treatment.31

Cell spreading along vascular wall is enhanced by perfusion culture

For successful re-endothelialization, that is, creation of a functional monolayer of endothelium, the cells must not only adhere but also spread along the inner lumen of the vessel.32 We hypothesized that spreading of the initially adhered cells might be facilitated/accelerated by exposing them to fluid shear stress analogous to the spreading and migration of ECs following vessel wall damage.33 Indeed, recent work with endothelial reseeded DLS showed that the application of increased fluid shear stress improved EC viability.34 In our study, after 1 h of static culture following seeding, numerous ECs were found within vessels, attached but not spread, and in some cases “clogging” the vessel (Fig. 8A). After 24 h exposure to low levels of fluid flow (3 mL/min), cells spread along the vessel walls with little or no cells found clogging the lumen. For example, in vessels ∼50 μm in diameter, in which the wall shear stress would be ∼0.15 dyn/cm2 at a flow rate of 3 mL/min, RLMVEC are spread along the vessel wall similar to an intact endothelium (Fig. 8B). According to Ren et al. this low flow rate, and, in turn, the fluid shear stress can be increased up to threefold (i.e., ∼0.42 dyn/cm2 in a 50 μm diameter vessel) without affecting cell viability.34 Although the flow rates used in ours and other's systems are less than the physiologic levels found in rodents (i.e., ∼150 mL/min/kg or 34.5 mL/min in a 0.23 kg rat35), the fact that these low shear stresses cause flattening and spreading is in line with previous data by Lelkes and Samet, who showed that cells respond to low shear stress by aligning with the flow although at a slower time scale.36 A gradual increase in perfusion rate could possibly aid in the spreading of cells throughout the vascular system.33

Improved barrier function following re-endothelialization

The data in Figure 9 clearly indicate that following perfusion culture of the re-endothelialized lungs for 1 week, the endothelium regains some of its function as a permeability barrier, as inferred from the ability of the reseeded endothelial monolayer to restrict the leakage of 150 kDa FITC-Dextran to nearly the same extent as the endothelium in intact lungs. We surmise that the formation of enhanced barrier function is related to the capability of RLMVECs to express ZO-1 at the boundary between adjacent confluent cells (Supplementary Fig. S7). Indeed, cultured ECs exposed in vitro to >5 dyn/cm2 shear stress increased their proliferation and the expression of junctional protein leading to enhanced barrier function of the EC monolayer.11 Additionally, in our study, the intact lung showed no leakage out of the parenchyma. The decellularized lung showed noticeable leakage from the parenchyma, and to a significantly lesser extent so did the recellularized lungs. A similar approach was recently described, where the perfusate was measured exiting not only out of the pulmonary vein, but also out of the trachea.5 In these experiments, studying the re-endothelialized pulmonary vasculature seeded with iPSC-derived ECs, the barrier function was recovered to ∼85% of that of the intact lung.5 In our model, the peak concentration of FITC-Dextran in the recellularized vascular compartment was about 95% of that in the intact lung, suggesting significant recovery of the endothelial barrier function following maturation of the reseeded endothelium. As a caveat, in our model clamping the trachea could have aided in retention of the perfusate in the recellularized vasculature. Again, ventilation during the perfusion/leakage studies would make this model more physiologically accurate.

Conclusion

In this study we have shown that the initial adhesion and distribution of ECs within the pulmonary vascular compartment of the DLS is significantly modulated by the posture in which the lungs are positioned during seeding. The difference can be seen at the whole organ scale, with considerably more cells residing in the RUL and LL, and at a vasculature-specific scale with more cells adhering to proximal vasculature in the supine position compared with the upright. This initial adhesion is followed by flattening/migration and proliferation of the seeded cells as the first steps toward complete re-endothelialization of the vascular tree, which is accelerated under perfusion culture. Future studies should consider the inclusion of ventilation during the seeding process, which would likely change the peripheral resistance within the vasculature. Multiple infusions through the same port and/or concomitant/sequential seeding through the pulmonary artery and vein, respectively, could increase the number of adhered cells. Future studies will focus on promoting angiogenic sprouting of the seeded ECs into the microvasculature and, in particular the alveolar capillary bed, to support the alveolar epithelium.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the numerous colleagues whose work we could not cite for space considerations. Our own studies were supported in part by a grant from NIH (5R01 HL-104258-02). P.I.L. is the Laura H. Carnell Professor for Bioengineering; M.R.W. is the Associate Chair of Physiology at Katz School of Medicine at Temple University whose contribution to this work was supported in part by DoD/ONR N000141210597 and N000141210810; C.T.S. is a NASA graduate student research program (GSRP) fellow (NNX13AP30H). P.L. holds the Jacob Gitlin Chair in Physiology at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and wishes to acknowledge the College of Engineering at Temple University for sabbatical financial support.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Valapour M., Paulson K., Smith J.M., Hertz M.I., Skeans M.A., Heubner B.M., Edwards L.B., Snyder J.J., Israni A.K., and Kasiske B.L. OPTN/SRTR 2011 Annual Data Report: lung. Am J Transplant 13 Suppl 1, 149, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scarritt M.E., Pashos N.C., and Bunnell B.A. A review of cellularization strategies for tissue engineering of whole organs. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 3, 43, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bae H., Puranik A.S., Gauvin R., Edalat F., Carrillo-Conde B., Peppas N.A., and Khademhosseini A. Building vascular networks. Sci Transl Med 4, 160ps23, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stabler C.T., Lecht S., Mondrinos M.J., Goulart E., Lazarovici P., and Lelkes P.I. Revascularization of decellularized lung scaffolds: principles and progress. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 309, 1273, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ren X., Moser P.T., Gilpin S.E., Okamoto T., Wu T., Tapias L.F., Mercier F.E., Xiong L., Ghawi R., Scadden D.T., Mathisen D.J., and Ott H.C. Engineering pulmonary vasculature in decellularized rat and human lungs. Nat Biotechnol 33, 1097, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song J.J., Kim S.S., Liu Z., Madsen J.C., Mathisen D.J., Vacanti J.P., and Ott H.C. Enhanced in vivo function of bioartificial lungs in rats. Ann Thorac Sur 92, 998, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petersen T.H., Calle E.A., Zhao L., Lee E.J., Gui L., Raredon M.B., Gavrilov K., Yi T., Zhuang Z.W., Breuer C., Herzog E., and Niklason L.E. Tissue-engineered lungs for in vivo implantation. Science 329, 538, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ott H.C., Clippinger B., Conrad C., Schuetz C., Pomerantseva I., Ikonomou L., Kotton D., and Vacanti J.P. Regeneration and orthotopic transplantation of a bioartificial lung. Nat Med 16, 927, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richter T., Bergmann R., Pietzsch J., Kozle I., Hofheinz F., Schiller E., Ragaller M., and van den Hoff J. Effects of posture on regional pulmonary blood flow in rats as measured by PET. J Appl Physiol 108, 422, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauters C., Marotte F., Hamon M., Oliviero P., Farhadian F., Robert V., Samuel J.L., and Rappaport L. Accumulation of fetal fibronectin mRNAs after balloon denudation of rabbit arteries. Circulation 92, 904, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seebach J., Dieterich P., Luo F., Schillers H., Vestweber D., Oberleithner H., Galla H.J., and Schnittler H.J. Endothelial barrier function under laminar fluid shear stress. Lab Invest 80, 1819, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonvillain R.W., Danchuk S., Sullivan D.E., Betancourt A.M., Semon J.A., Eagle M.E., Mayeux J.P., Gregory A.N., Wang G., Townley I.K., Borg Z.D., Weiss D.J., and Bunnell B.A. A nonhuman primate model of lung regeneration: detergent-mediated decellularization and initial in vitro recellularization with mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A 18, 2437, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price A.P., England K.A., Matson A.M., Blazar B.R., and Panoskaltsis-Mortari A. Development of a decellularized lung bioreactor system for bioengineering the lung: the matrix reloaded. Tissue Eng Part A 16, 2581, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daly A.B., Wallis J.M., Borg Z.D., Bonvillain R.W., Deng B., Ballif B.A., Jaworski D.M., Allen G.B., and Weiss D.J. Initial binding and recellularization of decellularized mouse lung scaffolds with bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Tissue Eng Part A 18, 1, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bur S., Bachofen H., Gehr P., and Weibel E.R. Lung fixation by airway instillation: effects on capillary hematocrit. Exp Lung Res 9, 57, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lecht S., Stabler C.T., Rylander A.L., Chiaverelli R., Schulman E.S., Marcinkiewicz C., and Lelkes P.I. Enhanced reseeding of decellularized rodent lungs with mouse embryonic stem cells. Biomaterials 35, 3252, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Senel Ayaz H.G., Perets A., Ayaz H., Gilroy K.D., Govindaraj M., Brookstein D., and Lelkes P.I. Textile-templated electrospun anisotropic scaffolds for regenerative cardiac tissue engineering. Biomaterials 35, 8540, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stabler C.T., Lecht S., Barakat M., Júnior L.C., Rylander A.L., Chiaverelli R., Schulman E.S., Marcinkiewicz C., and Lelkes P.I. Enhanced reseeding of decellularized rodent lung airway and vasculature. Presented at the Biomedical Engineering Society Annual Meeting, San Antonio, TX, Abstract No. 2500, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcinkiewicz C. Applications of snake venom components to modulate integrin activities in cell-matrix interactions. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 45, 1974, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stabler C.T., Junior L.C., Marcinkiewicz C., and Lelkes P.I. Integrin specific re-endothelialization within decellularized lungs. Presented at the Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine International Society World Congress, Boston, MA, Abstract No. 1973 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Girard E.D., Jensen T.J., Vadasz S.D., Blanchette A.E., Zhang F., Moncada C., Weiss D.J., and Finck C.M. Automated procedure for biomimetic de-cellularized lung scaffold supporting alveolar epithelial transdifferentiation. Biomaterials 34, 10043, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dintenfass L. Blood Microrheology: Viscosity Factors in Blood Flow, Ischaemia, and Thrombosis; An Introduction to Molecular and Clinical Haemorheology. New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1971 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Z., Xi R., Zhang Z., Li W., Liu Y., Jin F., and Wang X. 4-Hydroxyphenylacetic acid attenuated inflammation and edema via suppressing HIF-1alpha in seawater aspiration-induced lung injury in rats. Int J Mol Sci 15, 12861, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagao R.J., Ouyang Y., Keller R., Lee C., Suggs L.J., and Schmidt C.E. Preservation of capillary-beds in rat lung tissue using optimized chemical decellularization. J Mater Chem B Mater Biol Med 1, 4801, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maghsoudlou P., Georgiades F., Tyraskis A., Totonelli G., Loukogeorgakis S.P., Orlando G., Shangaris P., Lange P., Delalande J.M., Burns A.J., Cenedese A., Sebire N.J., Turmaine M., Guest B.N., Alcorn J.F., Atala A., Birchall M.A., Elliott M.J., Eaton S., Pierro A., Gilbert T.W., and De Coppi P. Preservation of micro-architecture and angiogenic potential in a pulmonary acellular matrix obtained using intermittent intra-tracheal flow of detergent enzymatic treatment. Biomaterials 34, 6638, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Price A.P., Godin L.M., Domek A., Cotter T., D'Cunha J., Taylor D.A., and Panoskaltsis-Mortari A. Automated decellularization of intact, human-sized lungs for tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 21, 94, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hill R.C., Calle E.A., Dzieciatkowska M., Niklason L.E., and Hansen K.C. Quantification of extracellular matrix proteins from a rat lung scaffold to provide a molecular readout for tissue engineering. Mol Cell Proteomics 14, 961, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernandez L.G., Le Cras T.D., Ruiz M., Glover D.K., Kron I.L., and Laubach V.E. Differential vascular growth in postpneumonectomy compensatory lung growth. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg 133, 309, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wallis J.M., Borg Z.D., Daly A.B., Deng B., Ballif B.A., Allen G.B., Jaworski D.M., and Weiss D.J. Comparative assessment of detergent-based protocols for mouse lung de-cellularization and re-cellularization. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 18, 420, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagenseil J.E., and Mecham R.P. Vascular extracellular matrix and arterial mechanics. Physiol Rev 89, 957, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walter D.H., Rittig K., Bahlmann F.H., Kirchmair R., Silver M., Murayama T., Nishimura H., Losordo D.W., Asahara T., and Isner J.M. Statin therapy accelerates reendothelialization: a novel effect involving mobilization and incorporation of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells. Circulation 105, 3017, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inoue T., Croce K., Morooka T., Sakuma M., Node K., and Simon D.I. Vascular inflammation and repair: implications for re-endothelialization, restenosis, and stent thrombosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 4, 1057, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gojova A., and Barakat A.I. Vascular endothelial wound closure under shear stress: role of membrane fluidity and flow-sensitive ion channels. J Appl Physiol 98, 2355, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren X., Tapias L.F., Jank B.J., Mathisen D.J., Lanuti M., and Ott H.C. Ex vivo non-invasive assessment of cell viability and proliferation in bio-engineered whole organ constructs. Biomaterials 52, 103, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sweet C.S., Emmert S.E., Seymour A.A., Stabilito II, and Oppenheimer L. Measurement of cardiac output in anesthetized rats by dye dilution using a fiberoptic catheter. J Pharmacol Methods 17, 189, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lelkes P.I., and Samet M.M. Endothelialization of the luminal sac in artificial cardiac prostheses: a challenge for both biologists and engineers. J Biomech Eng 113, 132, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.