Abstract

Objective

Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) has been shown to improve overall survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. This study aimed to assess the cost-effectiveness of SBRT compared to sorafenib which is the only drug for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma.

Methods

A Markov decision-analytic model was performed to compare the cost-effectiveness of SBRT and sorafenib for unresectable advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Patients transitioned between three health states: stable disease, progression disease and death. We calculated the data on cost from the perspective of our National Health Insurance Bureau. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine the impact of several variables.

Results

The incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) for sorafenib compared to SBRT was NT$3,788,238 per quality-adjusted life year gained (cost/QALY), which was higher than the willingness to pay threshold of Taiwan according to WHO’s guideline. One-way sensitivity analysis revealed that the utility of progression disease for the sorafenib treatment, utility of progression free survival for SBRT, utility of progression free survival for sorafenib, utility of PFS to progression disease for SBRT and transition probability of progression disease to dead for SBRT were the most sensitive parameters in all cost scenarios. The Monte-Carlo simulation demonstrated that the probability of cost-effectiveness at a willingness to pay threshold of NT$ 2,213,145 per QALY was 100 % and 0 % chance for SBRT and sorafenib.

Conclusion

This study indicated that SBRT for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma is cost-effective at a willingness to pay threshold as defined by WHO guideline in Taiwan.

Keywords: Cost-effectiveness analysis, ICER, Advanced hepatocellular carcinoma, Sorafenib

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide and Taiwan in 2012 and 2014, respectively [1, 2]. The incidence and mortality of HCC has continuously increased globally in North America and Asian countries [3–5]. The increased incidence of HCC is correlated with the high prevalence of cirrhosis hepatitis C virus, which did not have any vaccine for prevention [6]. HCC can be treated with surgical resection, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) or liver transplantation if diagnosed early [7, 8]. However, the majority of HCC patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage with poor liver function, a significant proportion of patients are incurable, with median survival rate are generally 1-year ranging from 20 to 30 % [9–11]. In patients with un-resectable HCC and contraindicated TACE, sorafenib is the only option that can increase 1-year survival to 45 %, particularly effective in patients with limiting extrahepatic spread [12, 13]. As the advances in technology of radiation planning and imaging, Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) is a radiation technique which deliver a higher radiation dose in few fractions to target lesions with low doses to the noninvolved liver. Therefore it has become a feasible and safe modern technique for patients with localized HCC and not eligible to TACE [14]. The radiation-induced liver disease (RILD) rates were less than 5 % [15]. Over the past decades, many studies have suggested that SBRT can be used safely with local control rates of 75 to 100 % at 1 to 2 years survival [14, 16–18]. Recently, the phase I and the subsequent phase II trial reported that SBRT improved the median overall survival about 17 months [16].

Although sorafenib and SBRT has showed an improvement in the median overall survival for the treatment of advanced HCC, the financial burden for its use are substantial. As the one payer healthcare system in our country, the healthcare expenditures have become one of the most important issues from the perspective of healthcare provider. This study was intended to compare whether sorafenib or SBRT is cost-effect for patients with inoperable advanced HCC.

Methods

Literature search strategy

A systematic literature search of the PubMed database was performed to identify all randomized controlled trials (RCT) of sorafenib or SBRT for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma from January 1, 1999, to March 31, 2016. The search strategy was based on combinations of (“unresectable” or “inoperable” or “advanced” or “metastatic” hepatocellular carcinoma” [Mesh]) and (SBRT or sorafenib [Mesh] (“randomized controlled trials” or” clinical trials” [Mesh]). We also searched cost-effectiveness studies using the medical subject headings or text key words: quality-adjusted, QALY, life-year gained (LYG) and cost-effectiveness. The appropriate full text was reviewed and evaluated by 2 reviewers (AC and HL) independently, using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria. RCT or clinical studies published in English that evaluated sorafenib or SBRT for mHCC were included. Letters to the editor, case reports, non randomized trials, animal studies, editorials and posters were excluded. Any discrepancies in inclusion were resolved by consensus. We finally selected one RCT and one clinical trial of sorafenib and SBRT for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma as the clinical data source of the model.

Markov model

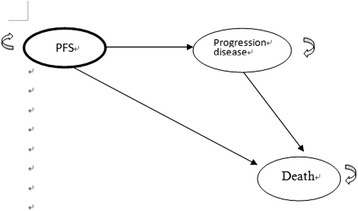

The decision-analytic Markov model comparing the cost-effectiveness of two different regimens over a 5-year time horizon was programmed in TreeAge Pro 2014 Suite (R1.0 Released; TreeAge Inc., Williamstown, MA). The clinical data of population modeled, adverse events and treatment protocol were based on the SHARP and Phase I/II clinical trials [12, 16]. As the experts’ opinion and referred to the published literature, three health states were considered in the model: stable disease, progression disease and death for inoperable advanced HCC (Fig. 1). A patient in the model was considered to be in one of three health states at any time. All patients began from the stable stage and transit from one state to another on the basis of the transition probabilities and received either sorafenib or SBRT according to the treatment regimen. All parameters were detailed in Table 1. Our model did not include deaths from natural causes occurring in any health state. Death from cancer was assumed to happen after disease progression. The model perspective was based on that of the National Health Insurance (NHI) in Taiwan, with a 1-month cycle length and adjusted to half-cycle in each health state process. The model time horizon was set to 5 years to avoid the exclusion of long-term survivors. All costs and health outcomes were discounted at a real annual rate of 3 % to adjust for the relative value of the Taiwan dollar at present. We used the definition of willingness to pay (WTP) threshold suggested by the World Health Organization (WHO): 3 times the per capita gross domestic product (GDP) [19, 20]. The Taiwan per capita GDP in 2015 was $ NT$737,715 (US$22,355) [21]; thus, a WTP threshold was considered as $ NT2,213,145/QALY. The outcomes of the analysis are expressed as incremental costs effectiveness ratio (ICER) which was the costs spent to gain a quality adjusted life-years (QALY). Model parameters were described in Table 1. A panel of local experts (blood oncologist and radiation oncologist and one expert in economic evaluations) was consulted to ensure that assumptions taken into consideration in the model reflected routine clinical practice.

Fig. 1.

The decision-analytic, Markov model schema. PFS, progression free survival

Table 1.

Base-case values and ranges used in sensitivity analyses (± 30 %)

| Parameters | Base estimate | Lower Limit- Upper Limit | Assumed distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Probability | |||

| PFS for sorafenib | 0.1533 | 0.1073–0.1993 | Beta |

| PFS To PD for sorafenib | 0.0627 | 0.044–0.082 | Beta |

| PD To death for sorafenib | 0.1184 | 0.063–0.154 | Beta |

| PFS for SBRT | 0.086 | 0.061–0.034 | Beta |

| PFS To PD for SBRT | 0.109 | 0.076–0.142 | Beta |

| PD To death for SBRT | 0.0399 | 0.028–0.052 | Beta |

| Utility | |||

| PFS for sorafenib | 0.76 | 0.546–1.014 | Beta |

| PD for sorafenib | 0.68 | 0.476–0.806 | Beta |

| PFS for SBRT | 0.72 | 0.504–0.936 | Beta |

| PD for SBRT | 0.63 | 0.441–0.819 | Beta |

| Direct Medical Costs (US$ = 33 NT) | |||

| cPFS for sorafenib | 563365 | 394355–732375 | Constant |

| cPFS for SBRT | 259056 | 181339–336773 | Constant |

| cPD for sorafenib | 417528 | 292270–542786 | Constant |

| cPD for SBRT | 417528 | 292270–542786 | Constant |

Abbreviations: c cost, SBRT sterotactic body radiation therapy, PFS progression free survival, PD progression disease

Treatment regimen

The outcome data from the SHARP and Phase I/II clinical trial were used [12, 16]. As expert opinions, the total radiation dose, sorafenib dose and schedule, patterns of treatment failure and survival of the regimen were assumed to be the same as those in the trials. According to the SHARP trial, patients were randomized to receive continuous sorafenib oral treatment with either 400 mg of sorafenib (consisting of two 200-mg tablets) twice daily for 6 week cycles. Tumor measurements were performed at screening, every 6 weeks during treatment (within 10 days before the end of each cycle), and at the end of treatment by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. Patients visited the clinic every 3 weeks and at the end of treatment for assessment of compliance, safety, and determination of side effects. The SBRT treatment regimen was according to the phase I/II trial, doses of 30 to 54 Gy (24 to 54 Gy in Trial 1) in six fractions every other day over 2 weeks were delivered to the planning target volume (PTV). The dose to tumor vascular thrombosis plus PTV margin could be limited to 30 Gy. Detailed description was in the trial [16].

Probabilities and utilities

Key probabilities for this model were included in Table 1. The trial did not collect probabilities and utility weights, therefore, the utilities were necessary to retrieve from the published literature [17, 18]. Transition probabilities of health states were estimated as follows: P(1 month) = 1- (0.5) (1/median PFS); this equation was derived from the following equations: P = 1 − e− RandR = − ln 〔0.5 〕/1 − (0.5)(1/median time)/number of treatment cycles) [22, 23]. The efficacies of sorafenib and SBRT treatment were extracted by Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the patients whose data were collected from two clinical trials.

Medical costs

The direct medical costs in this study were extracted from the National Health Insurance research database (NHIRD) and converted to 2015 NT dollar (1US$ = NT$ 33.0).The direct medical cost in this study included drug costs, laboratory test, physician visits, pharmacy dispensing fee, administration and nursing care fee. The drug costs for sorafenib and the costs of treatments for grade 3/4 adverse events (AE) were also included (Table 2). As a policy issued by the NHI, the reimbursement cost of SBRT is about NT$210,000 as a treatment package for early hepatocellular carcinoma and lung cancer, we therefore assumed this reimbursement cost for advanced HCC. We also assumed that the patient who survived by additional 1 month may produce the additional costs of visiting outpatient monthly.

Table 2.

Estimated cost inputs used in the model

| Cost input | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Cost administration and health States | ||

| PFS per course | ||

| Sorafenib | SBRT | |

| Drug or treatment cost | 537,264 | 210,000 |

| Costs of test: laboratory test, CT | 21,000 | 32,347 |

| Costs of physician visit, dispensing fee, nursing care | 3000 | 0 |

| Adverse events treatment | 38 | 16709 |

| Sub-total | 563,365 | 259,056 |

| PD per visit | ||

| Costs of test: laboratory test, CT | 10,728 | 10,728 |

| Costs of physician visit, dispensing fee, nursing care | 15,600 | 15,600 |

| End of life care | 391,200 | 391,200 |

| Sub-total | 417,528 | 417,528 |

Abbreviation: PFS progression free survival, PD progression disease, CT computerized tomography, SBRT stereotactic body radiotherapy

Sensitivity analysis

One-way sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine the potential impact of different parameters on this analysis; the result was presented as a tornado diagram. We hypothesized that the parameters varied over a range of ± 30 % in relation to its base-case value (Table 1).

The probabilistic sensitivity analysis using a Monte Carlo simulation was conducted to assess the impact of the uncertainty around the key parameters of the model on the ICER. That is, distributions for each parameter with the probabilistic sensitivity analysis were modeled. Log-normal distributions were adopted for all costs and beta distributions were adopted for probabilities, utilities and toxicity. The probabilistic sensitivity analysis was based on 10,000 samples, and the results were presented as a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve.

Toxicity

We considered only grade 3–4 toxicity associated with sorafenib or SBRT as the two clinical trials. The rate of drug-related severe toxicity caused permanent treatment and discontinuation of the drug was 11 % for sorafenib and 24.8 % for SBRT [12, 16].

Results

Patient baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the patients treated with sorafenib or SBRT were well balanced and no significant differences were noted with respect to sex, age, ECOG performance status, plasma levels of α-fetoprotein (AFP), Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging B and C. However, the percentage of Child-Pugh class A liver function, extrahepatic spread and vascular invasion were higher in SHARP trial compared to the Phase I/II trial (Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of the patients in the sharp and phase I/II trial

| Characteristics | SHARP trial | Phase I/II trial | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 64.9 | 69.4 | 0.22 |

| Male no (%) | 260 (87 %) | 80 (78.4 %) | 0.244 |

| Underlying liver disease | 0.011 | ||

| Hepatitis B | 56 (19 %) | 39 (38.2 %) | |

| Hepatitis C | 87 (29) | 39 (38.2 %) | |

| Alcohol related | 79 (26 %) | 25 (24.5 %) | |

| Other | 28 (9 %) | 14 (13.7 %) | |

| Unkown | 49 (16 %) | 7 (6.9) | |

| ECOG performance status n (%) | 0.225 | ||

| 0 | 161 (54 %) | 85 (83.3) | |

| 1 | 114 (38 %) | ||

| 2 | 24 (8 %) | 11 (10.8 %) | |

| BCLC stage | 0.208 | ||

| B (intermediate) | 54 (18 %) | 35 (34.3 %) | |

| C (advanced) | 244 (82 %) | 67 (65.7 %) | |

| Child-Pugh class, no (%) | < 0.0001 | ||

| A | 284 (95 %) | 102 (100 %) | |

| B | 14 (5 %) | 0 % | |

| Biochemical analysis | 0.25 | ||

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.9 | 4.0 | |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.7 | 1.3 | |

| Alpha-fetoprotein | 44.3 ng/ml | 163 nmol/L | |

| Previous therapy | 0.079 | ||

| Surgery | 57 (19 %) | 9 (8.8 %) | |

| TACE | 86 (29 %) | 22 (21.6 %) | |

| RFA | 17 (6 %) | 35 (34.3 %) | |

| PEI | 28 (9 %) | 16 (15.7 %) | |

| Extrahepatic spread (no,%) | 159 (53 %) | 12 (11.8 %) | < 0.0001 |

| Vascular invasion (no,%) | 108 (36 %) | 20 (49 %) | < 0.0001 |

Abbreviations: ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, BCLC Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging system, TACE transarterial chemoembolization, RFA radiofrequency ablation, PEI percutaneous ethanol injection

Direct medical costs

The direct medical costs of the drugs, laboratory test, physician visits, pharmacy dispensing fee, administration, nursing care fee and grade 3/4 AE treatments were shown in Table 2.

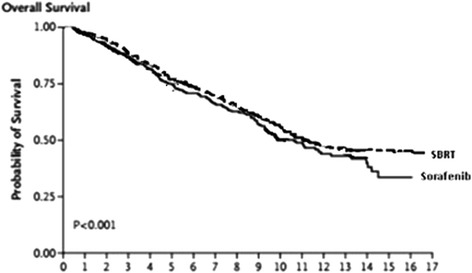

Effectiveness

The median overall survival (mOS) and median time to progression (mTTP) were 10.7 and 4.1 months in the sorafenib group of the SHARP trial, whereas, the mOS and mTPP were 17 and 6.0 months in the SBRT group from the Phase I/II trials, as shown in the Kaplan-Meier survival curves (Fig. 2). According to the equation described above, the monthly transition probability for PFS state was 0.153, from PFS to progression disease (PD) state was 0.0627, from PD state to death was 0.1184 for the sorafenib group. For SBRT, the monthly transition probability for PFS state was 0.086, from PFS to progression disease (PD) state was 0.109, from PD state to death was 0.0399 (Table 1). Utility scores of the health states were retrieved from two previously published studies (sorafenib group: 0.68 for PD, 0.76 for PFS; SBRT group: 0.63 for PD1, 0.72 for PFS1) [24, 25].

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier Analysis of Overall survival

Base-case analysis

The cost-effectiveness analysis demonstrated that the ICER for sorafenib compared to SBRT was NT$ 3,788,238 per quality-adjusted life year gained (cost/QALY) in the base scenario. Based on the WTP threshold of NT$ 2,213,145/QALY, the sorafenib was not cost-effective versus SBRT under the defined WTP threshold in this analysis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratios Comparing SBRT versus sorafenib at the Base Case

| Various cost | Sorafenib | SBRT |

|---|---|---|

| QALYs (years) | 3.07 | 2.81 |

| Incremental QALY gained (years) | 0.26 | - |

| Lifetime cost (US$) | 2166,079.7 | 1,197,039.2 |

| Incremental cost (NT$) | 969,041 | - |

| Cost/effectiveness | 704,857.96 | 426,117.13 |

| ICER (NT$) | 3,788,238 | |

| Cost-effectiveness threshold (NT$) | 2,213,145 | |

| Is SBRT cost-effective? | No | |

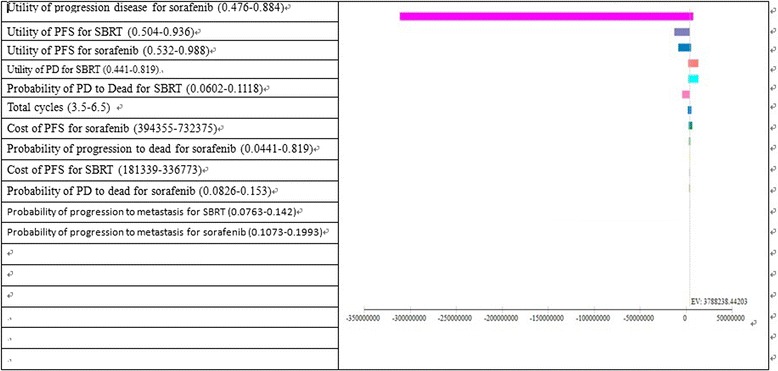

Sensitivity analyses

One-way sensitivity analysis was done for SBRT and sorafenib with a hypothesized variation of ±30 % in patients treated with two regimens by using the tornado diagram. The results showed the important parameters driving the model. The broader the horizontal bar in a tornado diagram, the more impact the input parameter has on the model. Analyses showed that the results of the model were highly sensitive to an assumption on the first five parameters, which were utility of progression disease for the sorafenib treatment, utility of progression free survival for SBRT, utility of progression free survival for sorafenib, utility of PFS to progression disease for SBRT and transition probability of progression disease to dead for SBRT (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Tornado analysis (ICER) for SBRT vs sorafenib. EV, expect value of ICER for gem + IMRT

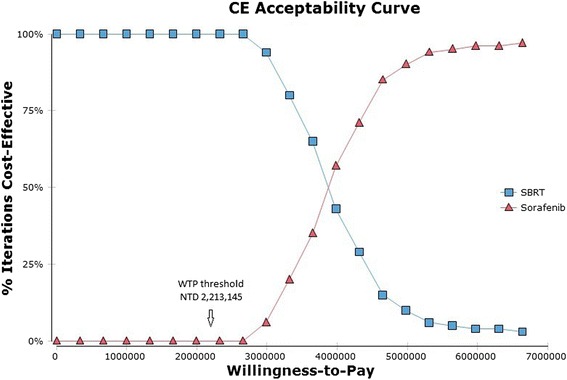

Probabilistic sensitivity analyze

Varying all variables simultaneously by ± 30 % in the Monte Carlo simulation, the results demonstrated that the probability of cost-effectiveness at a willingness to pay threshold of NT$ 2,213,145 per QALY was 100 % and 0 % chance for SBRT and sorafenib (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve. These probability that a specific treatment is cost-effective at a given Willingness-to-pay threshold of NT 2,213,145 (=US$ 67065, 1 US = 33 NT). SBRT, stereotactic body radiotherapy

Discussion

Sorafenib is currently used as the most effective option for patients with advanced un-resectable HCC and for those contraindicated to TACE [12]. The median overall survival of patients treated with sorafenib was 10.7 months. Most of the economic evaluation on sorafenib in unresectable HCC was cost-effective compared to best supportive care conducted in the USA [26, 27]. However, it was not a cost-effective option for patients with advanced HCC from the societal perspective in China [25]. Due to advances in radiotherapy planning and imaging technologies, SBRT have been suggested to be used safely for localized or unresectable advanced HCC with local control rate of 75–100 % at 1 to 2 years. Additionally, SBRT may provide better quality of life because of more favorable toxicity profile [16]. As the single payer Healthcare system in Taiwan, the high drug cost of sorfenib used for treating patients with advanced HCC have become one of the biggest issues. The decision-maker is probably willing to pay for less expensive and high outcome treatment for these patients. The result of this study is probably to provide the healthcare payer with evidence in determining a reasonable reimbursement price for the effective treatment strategy for patients with advanced HCC.

In our study, patients in the sorafenib group gained 3.07 QALYs at a cost of NT$ 2,166,079; patients in the SBRT group gained 2.81 QALYs at a cost of NT$1,197,039. Sorafenib increased 0.26 QALYs for these patients but with an incremental cost of NT$969,041 compared to SBRT. The ICER in our study was NT$ 3,788,238/QALY(US$114,795/QALY) for sorafenib versus SBRT treatment, which was significantly higher than the defined societal willingness to pay threshold in our country (NT$2,213,145/QALY = US$67,065/QALY) (Table 4). Therefore, sorafenib is not a cost-effective treatment for patients with unresectable advanced HCC in Taiwan. This result is consistent with the Zhang et al. study conducted in China because the dose of sorafenib used in their study was similar to that used by our oncologists in the field practice [25]. Furthermore, they also used the same definition of WTP as WHO’s guideline. However, the ICER in the Zhang et al. study was higher than that in our study. The reason may be the high percentage of vascular invasion in the patients collected in their study (macroscopic vascular invasion was 47.9 % versus ours 36 %, no data available to compare extrahepatic spread), which likely lead to a more unfavorable outcome in the sorafenib group in terms of TTP, OS and utility.

The high drug cost of sorafenib may be one of the key variables that have a great impact on the ICER as compared to placebo or other alternative regimen. The price of sorafenib reimbursed by the National Health Bureau was calculated based on the market price and negotiated with the manufacturer. The difference in the drug cost and other direct medical cost may result in different ICER value. On the contrary, SBRT is a cost-effective option for patients with unresectable advanced HCC under the assumption of reimbursement in our study. One-way sensitivity analysis revealed SBRT to be cost-effective regardless of the variation in any single parameter. As our expert opinion, the fixed reimbursement price of NT$ 210,000 per case may not affect the dose or technique of SBRT used for either early or unresectable advanced HCC. Therefore, from the perspective of single payer healthcare system, SBRT for the treatment of unresectable advanced HCC is likely to be cost-effective compared to sorafenib,

This study has some limitations. First, the perspective of our study was not societal. Only direct medical costs were involved, therefore, the costs may be underestimated. Second, our study did not consider dose adjustments (interruptions or reductions), it may have an impact on ICER value in sorafenib group. Third, the percentage of extrahepatic spread in patients of SHARP trial was higher than that in Phase I/II SBRT trial. This difference in patient characteristic is likely lead to a more unfavorable outcome in the sorafenib group in terms of TTP and OS, thus may have negative impact on the utility value. Fourth, the percentage of Child-Pugh class A liver function of patients recruited in SHARP trial and Phase I/II SBRT trial were 95 and 100 %. As reported by the GIDEON study [28], patients with advanced HCC with Child-Pugh class A liver function had a longer OS and TPP than those with Child-Pugh class B liver function. This difference may slightly have influence on the utility. However, the uncertainties associated with these limitations have been estimated by varying wide ranges of input parameters in sensitivity analyses and the results are robust.

Conclusion

Patients with unresectable advanced HCC within the patients’ criteria in our study, SBRT is more cost-effective than sorafenib in Taiwan.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This work did not require any written patient consent. The local ethics committee of Centre Jean Perrin approved this work.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Acknowledgements

This study did not support by any fund. We did not acknowledge anyone for the contribution towards the study.

Funding

This work did not receive any specific funding.

Abbreviations

- BCLC

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging system

- EGOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- ICER

incremental cost effectiveness ratio

- mHCC

metastasis hepatocellular carcinoma

- mOS

median overall survival

- mTTP

median time to progression

- P

transition probability

- PD

progression state

- PFS

progression free survival

- PTV

planning target volume

- QALY

quality adjusted life year

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SBRT

stereotactic body radiotherapy

- WTP

willingness to pay

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AC conceived the study, builds the model and analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript; HL participated in the study design and interpretation and oncology expert. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/. Accessed 13 Feb 2016.

- 2.Taiwan cancer registry. http://tcr.cph.ntu.edu.tw/main.php?Page=N2. Accessed 13 Feb 2016.

- 3.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma: an epidemiologic view. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:S72–8. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200211002-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Reichman ME. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States from 1975 to 2005. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1485–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finn RS. Development of molecularly targeted therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma: where do we go now? Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:390–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruix J, Sherman M, Practice Guidelines Committee et al. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208–36. doi: 10.1002/hep.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37:429–42. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliveri RS, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Transarterial (chemo)embolisation for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004787.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng M, Ben-Josef E. Radiation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2011;21:271–7. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A, Schwartz M, Porta C, Zeuzem S, Bolondi L, Greten TF, Galle PR, Seitz JF, Borbath I, Häussinger D, Giannaris T, Shan M, Moscovici M, Voliotis D, Bruix J, SHARP Investigators Study Group Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, Luo R, Feng J, Ye S, Yang TS, Xu J, Sun Y, Liang H, Liu J, Wang J, Tak WY, Pan H, Burock K, Zou J, Voliotis D, Guan Z. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tse RV, Hawkins M, Lockwood G, Kim JJ, Cummings B, Knox J, Sherman M, Dawson LA. Phase I study of individualized stereotactic body radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinomaand intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):657–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maor Y, Malnick S. Liver injury induced by anticancer chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Int J Hepatol. 2013;2013:815105. doi: 10.1155/2013/815105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bujold A, Massey CA, Kim JJ, Brierley J, Cho C, Wong RK, Dinniwell RE, Kassam Z, Ringash J, Cummings B, Sykes J, Sherman M, Knox JJ, Dawson LA. Sequential phase I and II trials of stereotactic body radiotherapy for locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(13):1631–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cammà C, Cabibbo G, Petta S, Enea M, Iavarone M, Grieco A, Gasbarrini A, Villa E, Zavaglia C, Bruno R, Colombo M, Craxì A, WEF study group. SOFIA study group Cost-effectiveness of sorafenib treatment in field practice for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2013;57(3):1046–54. doi: 10.1002/hep.26221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonnetain F, Paoletti X, Collette S, Doffoel M, Bouché O, Raoul JL, Rougier P, Masskouri F, Barbare JC, Bedenne L. Quality of life as a prognostic factor of overall survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: results from two French clinical trials. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(6):831–43. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9365-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray CJ, Evans DB, Acharya A, Baltussen RM. Development of WHO guidelines on generalized cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Econ. 2000;9(3):235–51. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(200004)9:3<235::AID-HEC502>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Statistics times: International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook (April-2015) http://statisticstimes.com/economy/projected-world-gdp-capita-ranking.php. Accessed 24 Jan 2016

- 21.Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan). http://taiwantoday.tw/ct.asp?xItem=239566&ctNode=435. Accessed 24 Jan 2016

- 22.Leung HW, Chan AL, Muo CH. Cost-effectiveness of Gemcitabine Plus Modern Radiotherapy in Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Clin Ther. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Purmonen T, Markainen JA, Soini EJ, Kataja V, Vuorinen RL, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL. Economic evaluation of sunitinib malate in second-line treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma in Finland. Clin Ther. 2008;30:382–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLernon DJ, Dillon J, Donnan PT. Health-state utilities in liver disease: a systematic review. Med Decis Making. 2008;28(4):582–92. doi: 10.1177/0272989X08315240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang P, Yang Y, Wen F, He X, Tang R, Du Z, Zhou J, Zhang J, Li Q. Cost-effectiveness of sorafenib as a first-line treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27(7):853–9. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carr BI, Carroll S, Muszbek N, Gondek K. Economic evaluation of sorafenib in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25(11):1739–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoyle M, Green C, Thompson-Coon J, Liu Z, Welch K, Moxham T, Stein K. Cost-effectiveness of sorafenib for second-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Value Health. 2010;13(1):55–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lencioni R, Marrero J, Venook A, Ye SL, Kudo M. Design and rationale for the non-interventional Global Investigation of Therapeutic DEcisions in Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Of its Treatment with Sorafenib (GIDEON) study. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(8):1034–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.