Abstract

Progesterone (P4) exerts robust cytoprotection in brain slice cultures (containing both neurons and glia), yet such protection is not as evident in neuron-enriched cultures, suggesting that glia may play an indispensable role in P4's neuroprotection. We previously reported that a membrane-associated P4 receptor, P4 receptor membrane component 1, mediates P4-induced brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) release from glia. Here, we sought to determine whether glia are required for P4's neuroprotection and whether glia's roles are mediated, at least partially, via releasing soluble factors to act on neighboring neurons. Our data demonstrate that P4 increased the level of mature BDNF (neuroprotective) while decreasing pro-BDNF (potentially neurotoxic) in the conditioned media (CMs) of cultured C6 astrocytes. We examined the effects of CMs derived from P4-treated astrocytes (P4-CMs) on 2 neuronal models: 1) all-trans retinoid acid-differentiated SH-SY5Y cells and 2) mouse primary hippocampal neurons. P4-CM increased synaptic marker expression and promoted neuronal survival against H2O2. These effects were attenuated by Y1036 (an inhibitor of neurotrophin receptor [tropomysin-related kinase] signaling), as well as tropomysin-related kinase B-IgG (a more specific inhibitor to block BDNF signaling), which pointed to BDNF as the key protective component within P4-CM. These findings suggest that P4 may exert its maximal protection by triggering a glia-neuron cross talk, in which P4 promotes mature BDNF release from glia to enhance synaptogenesis as well as survival of neurons. This recognition of the importance of glia in mediating P4's neuroprotection may also inform the design of effective therapeutic methods for treating diseases wherein neuronal death and/or synaptic deficits are noted.

Progesterone (P4), the natural progestin, is a major gonadal hormone synthesized primarily by the ovary in females, and the testes and adrenal cortex in males. P4 is also synthesized in astrocytes within the brain, thus considered to be a neurosteroid as well (1). Although the function of P4 has historically been considered within the context of the reproductive system, it is now clear that P4 has important effects on multiple organ systems including the brain. P4 has been reported to exert protective effects in numerous experimental models that mimic a variety of age-associated brain diseases, including ischemic stroke (2–4), Alzheimer's disease (AD) and traumatic brain injury (TBI) (5–9). For example, acute administration of P4 enhanced learning and spatial working memory performance in both male and female middle-aged and aged mice (10, 11). Despite the promising experimental and preclinical data, a recent phase III clinical trial (ProTECT III) assessing the efficacy of P4 treatment for acute TBI showed rather disappointing results with no favorable effects noted while increasing the frequencies of phlebitis (12). Such discrepancies between animal and human data further underscore the critical need to better understand the mechanisms of P4 action in the central nervous system, so as to better inform future studies that address either acute insults (such as TBI) or chronic neurodegenerative diseases (such as AD).

Characteristic neuropathological changes of AD include both neuronal loss and synapse loss (13). Of note, P4 has been shown to promote neuronal survival as well as synaptogenesis (14, 15). One potential downstream mediator of P4's effect on neuronal survival and synaptogenesis is brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF belongs to the family of neurotrophins, which play key roles in the brain to support cell survival and synaptic plasticity (16, 17) and is synthesized in both neurons and glia (18, 19). BDNF is synthesized as a glycosylated precursor (prepro-BDNF), processed into a 35-kDa pro-BDNF and then can be converted into the 14-kDa mature BDNF (20, 21). BDNF released from cells elicits its effects by binding to tropomysin-related kinase (Trk)B (a tyrosine kinase family of receptors) and/or the p75 neurotrophin receptor (19, 20, 22, 23). Delineating the effects of pro- vs mature BDNF is critical, because they can exert opposite biological functions such that mature BDNF binds to the TrkB receptor to influence neuronal survival, differentiation, and promote long-term potentiation, whereas pro-BDNF binds preferentially to p75NTR and can induce neuronal apoptosis and promote LTD (21). Moreover, it has been proposed that neuronal dysfunction or atrophy consequent to aging or age-associated diseases may result from not only decreases in mature neurotrophin expression or function (24–26) but, potentially, to increased accumulation of the proneurotrophins.

We recently found that glia and neurons showed an interesting and striking difference in not only basal release of BDNF but also in their response to P4. Glia exhibited low levels of basal BDNF secretion, and responded significantly to treatment with P4 (27). In characterizing the mechanism by which P4 increased the release of BDNF, we found that a novel membrane-associated P4 receptor (MAPR) (P4 receptor membrane component 1 [Pgrmc1]) was responsible for the P4-elicited BDNF release from glia (27). Pgrmc1 has been implicated as an important biomarker for cancer progression and as a potential target for anticancer therapies (28). With regard to the brain, expression of Pgrmc1 has been mapped to the cerebral cortex, hypothalamus, amygdala, and cerebellum (29–31). With respect to neuroprotection, Guennoun et al showed the potential role of Pgrmc1 in mediating the protective effects of P4 in the injured spinal cord and in the brain after TBI (31). Furthermore, Guennoun et al also showed that Pgrmc1 expression was up-regulated after TBI in both cortical neurons as well as in the astrocytes near the lesion (31), suggesting that Pgrmc1 may influence P4-stimulated glial responses after injury as well.

In this study, we sought to determine whether glia are required for P4's neuroprotection and whether the roles of glia are mediated, at least partially, by releasing soluble factors to act on neighboring neurons. Our data demonstrated that P4 increased the ratio of mature to pro-BDNF in astrocytes and that the conditioned media (CMs) from P4-treated astrocytes (P4-CMs) was effective at promoting an increase in synaptic marker expression and neuronal viability. Interestingly, the protective effects of P4-CM were prevented by inhibiting BDNF signaling. Together, our data support a critical role for astrocytes in mediating the protective effects of P4 and, further, that these protective effects are mediated, at least in part, through the regulation of BDNF signaling.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and treatment

Rat C6 glioma cells (male) and human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells (female) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. C6 cells were propagated in DMEM (Invitrogen Life Technologies) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (noncharcoal-stripped) (HyClone) and maintained at 37°C in a humidified environment containing 5% CO2 for 24 hours, then treated with vehicle control-dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (0.1%), P4 (Sigma-Aldrich) at 10nM for the indicated time. SH-SY5Y cells were differentiated with all-trans retinoic acid (RA) (Sigma-Aldrich) at 10μM for 7 days. At day 5, cells were conditioned to 15% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (HyClone) for another 48 hours.

The use of animals for the purpose of generating primary cultures was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of North Texas Health Science Center. All mice were handled according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Primary cultures of cortex and hippocampal neurons were prepared from neonatal murine pups (C57BL/6NHSd mice; Harlan) as described by Sarkar et al (32) with modifications (33). Briefly, hippocampal tissues isolated from newborn mice (postnatal d 2–4, mixed gender) were dissociated with trypsin and deoxyribonuclease I for 10 minutes at 37°C. The tissues were then washed twice with Neurobasal-A medium containing B-27 and further dissociated by gentle titration using a graded series of fine polished Pasteur pipettes. After centrifugation at 200g for 3 minutes at 4°C, cortex and hippocampal neurons were resuspended in Neurobasal-A/B-27 medium, passed through a cell strainer with 70-μm mesh, and plated at 1.0 × 105 cells/cm2 on culture dishes precoated with poly-D-lysine. The culture dishes were kept at 37°C in humidified 95% air and 5% CO2. The initial culture medium was replaced after 5 hours; subsequently, half of the medium was changed every 3 days. At day in vitro (DIV) 2, 1-β-arabinofuranosylcytosine was added to a final concentration of 5μM to prevent glial proliferation. Treatments of the primary cultures started at DIV 7.

For SH-SY5Y cells or primary neurons experiments, there were 6 groups: 1) nontreated (labeled as “control”); 2) BDNF (Millipore) treated, added at 100 ng/mL; 3) DMSO condition medium (DMSO-CM) treated; 4) P4-CM treated; 5) DMSO-CM with neurotrophin antagonist, Y1036 (Millipore), at 40μM; and 6) P4-CM with Y1036.

In experiments in which TrkB-IgG was used, recombinant human TrkB-Fc chimera (R&D Systems) or normal human IgG was added to glial CM at 4.0 μg/mL for 2 hours in 4°C with rotation. Then the glial CM was added to the differentiated SH-SY5Y cells or primary neuronal cultures.

Pgrmc1 pull-down assay

Dynabeads Protein A were purchased from Life Technologies. In advance of the experiment, Dynabeads Protein A was coated with anti-Pgrmc1 antibody (ab48058; Abcam). Briefly, 400 μL of Dynabeads Protein A suspension was attached to DynaMag-2 (Life Technologies), and the supernatant was removed. Dynabeads Protein A were resuspended in 800 μL of wash buffer (100mM phosphate buffer containing 0.05% Tween 20; pH 7.4) containing 40 μL of the antibody, and incubated at 4°C overnight with head-to-tail rotation. Immediately before the experiment, Dynabeads Protein A were washed with wash buffer 5 times and resuspended in 800 μL of wash buffer; 25-μL suspension of Dynabeads Protein A: anti-Pgrmc1 Ab complex was added to 1 mL of C6 cell supernatants (enriched from 20-mL total culture supernatants; see following). After incubation at room temperature for 60 minutes, the Dynabeads Protein A were washed with 250 μL of wash buffer 5 times and resuspended in 25 mL of 1× SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Pro- and mature BDNF was separated by different molecular weight on Western blotting (for antibodies, please see Table 1).

Table 1.

Antibody Table

| Peptide/Protein Target | Antigen Sequence (if Known) | Name of Antibody | Manufacturer, Catalog Number, and/or Name of Individual Providing the Antibody | Species Raised in; Monoclonal or Polyclonal | Dilution Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAP43 | Anti-GAP43 | Abcam, ab75810 | Rabbit; monoclonal | 1:1000 | |

| GAPDH | Anti-GAPDH | Cell Signaling, 2118 | Rabbit; monoclonal | 1:1000 | |

| Pro- and mature BDNF | Anti-BDNF | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, sc-546 | Rabbit; polyclonal | 1:1000 | |

| SYP | Anti-SYP | Abcam, ab14692 | Rabbit; polyclonal | 1:1000 | |

| Total BDNF | Anti-BDNF | Abcam, ab6201 | Rabbit; polyclonal | 1:1000 |

Column enrichment of C6 culture supernatants

In experiments in which primary neurons were used, 20 mL of C6 CMs were harvested and transferred to a prerinsed Pierce 9K MWCO 20-mL concentrator (Thermo Scientific), after centrifuge at 3200 rpm for 45 minutes to achieve a final concentrated volume of 1 mL. The concentrated CM was sterilized via a 0.2-μm sterile syringe filter and then applied to cultures in volumes to dilute back to 1×.

Immunocytochemistry quantification

SH-SY5Y cells were differentiated with 10μM all-trans RA for 7 days before being treated with glial-derived DMSO-CMs or P4-CMs in the presence or absence of Y1036. Treatment of cells with BDNF was used as positive control. At the end of treatment, cells were briefly washed with cold PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature. Fixed cells were permeablized with cold methanol:acetone (1:1) for 1 minute. The cells were then washed with cold PBS and incubated with 2% normal goat serum in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. The cells were incubated with the rabbit anti-Growth Associated Protein 43 (GAP43) antibody (ab75810; Abcam), in PBS containing 2% normal goat serum at 4°C overnight. After several washes with cold PBS, they were then incubated with green-fluorescent dye-labeled goat antirabbit IgG antibody (Invitrogen Life Technologies) for 1 hour at room temperature. After 2 washes with cold PBS, cells were then incubated with Hoechst dye at room temperature for 15 minutes. Stained cultures were preserved in PBS at 4°C. Images were acquired with a Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope (×20) with strict preservation of imaging setting across samples. Mean fluorescence intensity values were measured by drawing a rectangle (20 × 10 pixels in dimension) and aligning the box such that it enclosed the area of interest, the region of interest function of the Nikon Instruments Software elements software were then used to compute a mean fluorescence intensity value. For each treatment group, GAP43 mean fluorescence intensities of 3–5 nonoverlapping proximal and distal neuritic segments were measured, and average values were computed. A proximal segment is defined as a section within 2 length of a cell body and a distal neuritic segment is anywhere greater than 2 length of a cell body that it originates from. Mean intensity values were then normalized to nontreated control group and reported as percentage of control. Three to 4 independent experiments were performed.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was isolated from SH-SY5Y cell, primary neuron cultures and mouse brains using the RNeasy Mini kit and the RNeasy Lipid kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Concentrations of extracted RNA were determined using absorbance values at 260nM. The purity of RNA was assessed by ratios of absorbance values at 260nM and 280nM (A260 to A280 ratios of 1.9:2.0 were considered acceptable). Total RNA (1.6 μg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA in a total volume of 20 μL using the High-Capacity DNA Archive kit (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Primers and probes for quantitative real-time RT-PCR

PCR primers and probes for the target gene were purchased as Assay-On-Demand (Applied Biosystems, Inc). The assays were supplied as a 20 mix of PCR primers (900nM) and TaqMan probes (200nM). The BDNF (Mm00432069_m1), Pgrmc1 (Mm00443985_m1), GAP43 (Hs00967138_m1), synaptophysin (SYP) (Hs00300531_m1), and Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Hs02758991_g1 and Mm03302249_g1) assays contained 6-carboxy-fluorescein phosphoramidite dye label at the 5′ end of the probes and minor groove binder and nonfluorescent quencher at the 3′ end of the probes.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

The reaction mixture contained water, 2× quantitative PCR Master Mix (Eurogentec), and 20× Assay-On-Demand for each target gene. A separate reaction mixture was prepared for the endogenous control, GAPDH. The reaction mixture was aliquoted in a 96-well plate, and cDNA (30-ng RNA converted to cDNA) was added to give a final volume of 30 μL. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. Amplification and detection were performed using the ABI 7300 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) with the following profile: 2-minute hold at 50°C (uracil-N-glycosylase) and 10-minute hold at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C (denaturation) and 1 minute at 60°C (annealing and extension). Sequence Detection Software version 1.3 (Applied Biosystems) was used for data analysis. The comparative cycle threshold (Ct) method (2−ΔΔCt) was used to calculate the relative changes in target gene expression. In the comparative Ct method, the amount of target, normalized to an endogenous control (GAPDH) and relative to a calibrator (untreated control), is given by the 2−ΔΔCt equations. Quantity is expressed relative to a calibrator sample that is used as the basis for comparative results. Therefore, the calibrator was the baseline (nontreated control) sample, and all other treatment groups were expressed as an n-fold (or percentage) difference relative to the control (40). The average and SD of 2−ΔΔCt was calculated for the values from 5 independent experiments, and the relative amount of target gene expression for each sample was plotted in bar graphs using GraphPad Prism version 4 software (GraphPad).

Western blotting

Cells were harvested with lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors, as described previously (34). After homogenization, samples were centrifuged at 12 000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C, and the resulting supernatants were evaluated for total protein concentrations using the Bio-Rad DC (Bio-Rad Laboratories) protein assay kit. Sample lysates were loaded onto a sodium dodecyl sulfate/10% polyacrylamide gel, subjected to electrophoresis, and subsequently transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (0.22-μm pore size; Bio-Rad Laboratories). The membrane was blocked for 1 hour with 5% nonfat milk in 0.2% Tween-containing Tris-buffered saline solution before application of the primary antibody. The following primary antibodies were used. The antibodies against pro- and mature BDNF (N20, 1:1000) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc; the antibodies against total BDNF, SYP, and GAP43 (1:1000) were purchased from Abcam; the antibodies against GAPDH (14C10, 1:1000) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology.

Antibody binding to the membrane was detected using a secondary antibody (either goat antirabbit or rabbit antigoat) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:20 000; Pierce Chemical Co) and visualized using enzyme-linked chemiluminescence (Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate; Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the aid of the Alpha Innotech imaging system.

Apoptotic assay

Apoptosis was quantified using the Vybrant apoptosis assay kit (Invitrogen) per manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, Hoechst 33342 solution (1:2000) was added to cells cultured in 6-well plate, and the mixture was incubated for 30 minutes on ice. Fluorescence was measured under a fluorescence microscope with a ×20 objective. The blue fluorescent dye Hoechst 33342 stains chromatin of apoptotic nuclei more vividly than nonapoptotic nuclei. Apoptotic cells were quantified from 3 random nonoverlapping fields per well. Results are expressed as percentage of apoptotic cells (100 × Hoechst-positive cells/number of cells per field).

Statistical analysis

Densitometric analysis of the Western blottings was conducted using Alpha Innotech Image Analysis software (Cell Biosciences). For each figure, at least 3 independent experiments were conducted. All the quantification data were presented as ratio or percentage normalized to control in bar graph depicting the average ± SEM, using GraphPad Prism software. For statistical analysis of Western blotting band intensities and fluorescence intensities, the raw numbers were used and analyzed using two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni post hoc test for the assessment of differences between groups. We used Anderson-Darling test on the raw data to confirm that data in each treatment group (ie, control, or BDNF, etc) have P > .05, indicating that the normality assumption is reasonable.

For data in Figure 1 (pull-down BDNF from glial culture media), the fact that we replicated this experiment 3 time precludes the ability to conduct an assessment of whether the data were normally distributed. However, the differences between P4-treated groups and other groups were quite large and bolster our confidence in concluding that such differences are indeed significant.

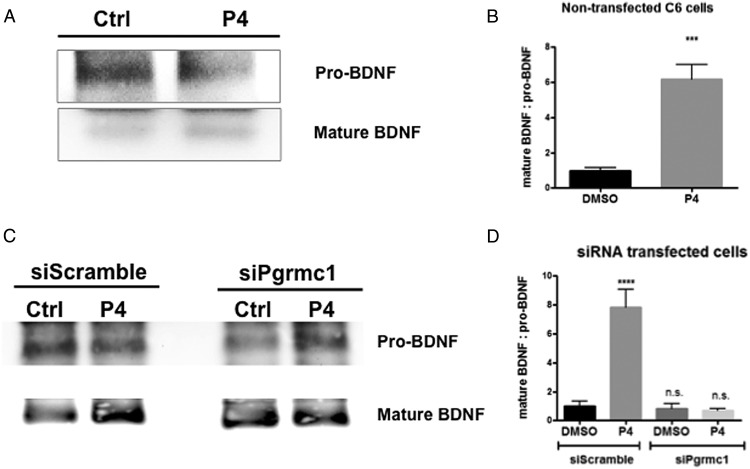

Figure 1.

P4 increases the ratio of mature to pro-BDNF released from glia. Western blotting of the BDNF-immunopreciptated CMs was used to measure the relative amounts of the forms of BDNF (mature and pro-BDNF) in nontransfected C6 cells (A and B) and scrambled siRNA (siScramble), or siRNA against Pgrmc-1 (siPgrmc-1) transfected C6 cells between groups of DMSO-CM and P4-CM (C and D). P4 increased the ratio of mature to pro-BDNF released from glia cells and siPgrmc1 abolished P4-induced beneficial effect of BDNF releasing. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM, n = 3 per group; ***, P < .001; ****, P < .0001, DMSO vs P4.

The quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction data are not normally distributed. We have revised our analysis to the use of raw data in nonparametric ANOVA for the assessment of differences between groups.

Results

P4 increased the ratio of mature to pro-BDNF released from glia

We previously reported that P4 elicits the release of total BDNF from astroglia. Here, we extended these findings to demonstrate that the levels of mature BDNF increased, whereas the level of pro-BDNF decreased, in the CMs of P4-treated C6 astrocyte cultures (Figure 1, A and B). To determine whether the effect of P4 on this increased ratio of mature to pro-BDNF was mediated by a novel MAPR, Pgrmc1, we used RNA interference-mediated gene depletion to knock down the expression of Pgrmc1 in C6 cells, as conducted in previously published studies (26). Western blotting of the BDNF-immunopreciptated CMs was used to measure the relative amounts of the forms of BDNF (mature and pro-BDNF). Our data revealed that Pgrmc1 depletion completely prevented the effect of P4 on the ratio of mature to pro-BDNF (Figure 1, C and D). These results suggest that P4 increases the ratio of mature to pro-BDNF released from glia through a Pgrmc1-dependent mechanism.

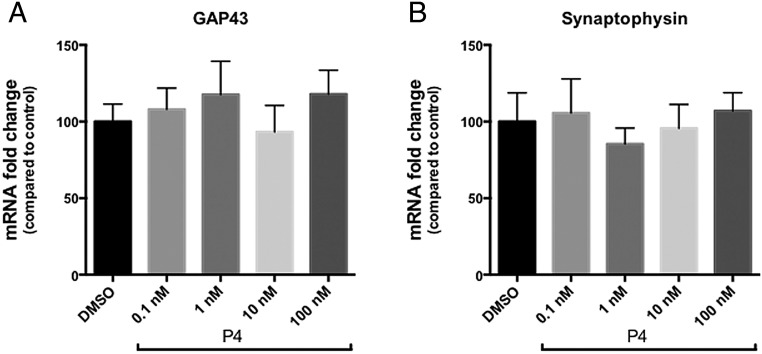

P4 did not change the mRNA levels of synaptic markers in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells

To test whether P4 directly affects the expression of synaptic markers, we tested its effect on a widely used neuronal model, the all-trans RA-differentiated SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. We directly added P4 (ranged from 0.1nM to 100nM) into the these cells and measured the mRNA levels of GAP43 (Figure 2A) and SYP (Figure 2B) using quantitative real-time PCR. GAP43 is a protein mainly synthesized during axonal outgrowth during neuronal development and regeneration (34), and SYP is a presynaptic marker usually expressed highly during neuronal remodeling (35). Compared with the DMSO vehicle control, treatments with this wide concentration range of P4 did not show any difference in GAP43 and SYP levels. These data suggest that P4, when directly added into neuronal cultures, does not affect the synaptic marker expression.

Figure 2.

P4, when directly added into differentiated SH-SY5Ycells, did not affect the mRNA levels of GAP43 and SYP. P4 (diluted to a final concentration of 0.1nM, 1nM, 10nM, or 100nM in DMSO) was added into differentiated SH-SY5Y cultures for 24 hours. The same dilutions of DMSO were used as the control for each P4 concentration. mRNA levels of GAP43 (A) and SYP (B) were determined by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Data from the DMSO groups were set at 100%, and data from each corresponding P4 concentration were presented as percentage compared with the DMSO control. There was no statistical difference across all the treatments.

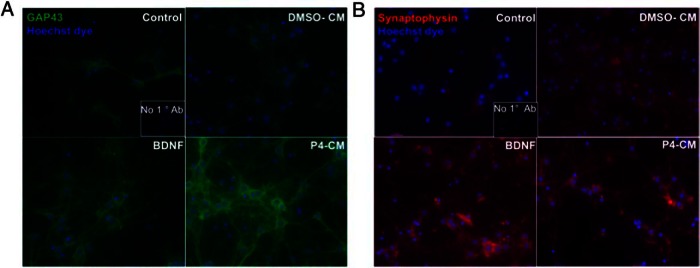

P4-CM triggers synaptic marker expression in primary neurons

Next, we sought to test the hypothesis that P4 affects neuronal function indirectly via a glial-mediated mechanism (ie, triggering the release soluble factors such as BDNF from glia to act on neighboring neurons). We examined the effects of CMs derived from P4-treated C6 astrocytes (P4-CM) on synaptic marker expression in neurons. We first used mouse neuron-enriched primary hippocampal cultures. In order to avoid the potential confound of the P4 transferred from the glial CM to the neurons to increase BDNF release, we used a 9-kDa molecular mass cut-off column to collect the neurotrophic factors released (found in the retentate) while allowing the free P4 to be filtered through and discarded. We used the ELISA to confirm that P4 indeed was significantly reduced from the retentate of the filtered CMs (data not shown). The retentate was then reconstituted and applied to the neuronal cultures. Cells exposed to purified recombinant BDNF were used as positive control in all the following experiments, as we compared the effects of glial P4-CM with the purified BDNF. Using double immunofluorescent labeling, we found that glial P4-CM enhanced expression of GAP43 (Figure 3A) and SYP (Figure 3B) in primary hippocampal neurons.

Figure 3.

P4-CM triggers synaptic marker expression in mouse hippocampal neurons. Mouse primary hippocampal neurons were exposed with nontreated control, BDNF, DMSO-CM, or P4-CM for 24 hours at DIV 7. Double-label immunofluorescence staining shows that expression of synaptic markers, (A) GAP43 (green) and (B) SYP (red), were enhanced by glial P4-CM in primary hippocampal neurons. Hoechst dye (blue) was used to counterstain nuclei. Insets show staining without GAP43 or SYP primary antibodies at a higher magnification. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Glial P4-CM increased SYP and GAP43 expression in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells

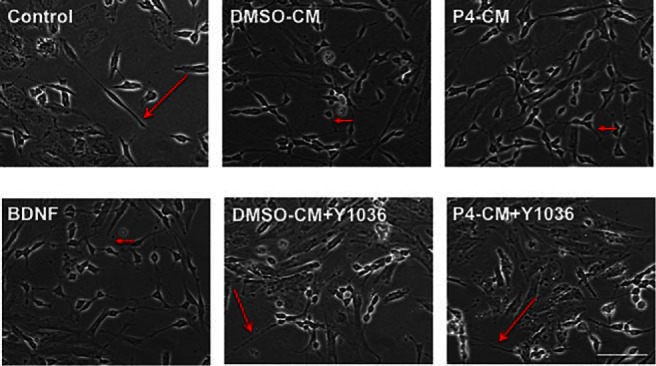

To further elucidate the underlying mechanisms of P4-CM on induction of synaptic marker expression, we tested its effect on differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. At the end of the 7 day all-trans RA differentiation, SH-SY5Y cells form a network of long and smooth neurites (Figure 4, long arrows). P4-CM or BDNF treatments induced an increase in dendritic sprouting, promoting a complex synaptic connection network in differentiated SH-SY5Y culture. These changes were also observed in the DMSO-CM group, but to a lesser extent, in agreement with our previous findings that glia secrete BDNF independently of exogenous stimulation at a modest rate. Importantly, effects of P4-CM were attenuated by Y1036, a neurotrophin signaling antagonist (36), indicating that the beneficial effect of glial P4-CM on synaptogenesis in SH-SY5Y cells may be mediated by neurotrophic factors. These morphological changes were prominent up to 24 hours after P4-CM exposure.

Figure 4.

P4-CM induced morphological change in SH-SY5Y cells. SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells were differentiated with RA for 7 days and formed a network of long and smooth neuritis (long arrows) at 24 hours exposed with nontreated control, BDNF, DMSO-CM, or P4-CM in the presence or absence of the neurotrophin antagonist Y1036. P4-CM or BDNF treatment induced an increase in dendritic sprouting, promoting a complex synaptic connection network in differentiated SH-SY5Y culture. These changes were also observed in the DMSO-CM group but to a lesser extent. The effects of P4-CM on dendritic process formation were attenuated by Y1036. Scale bar, 100 μm.

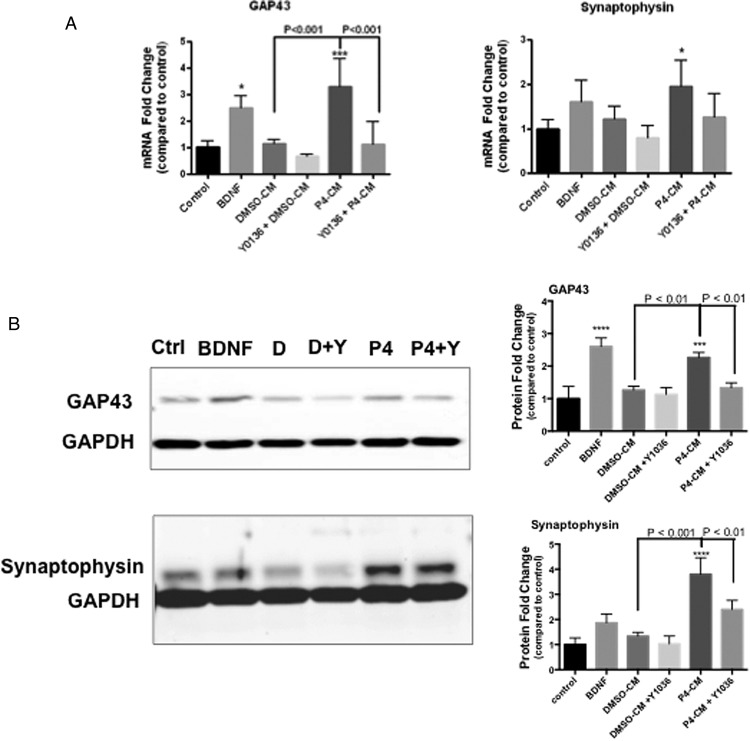

We also quantified the transcript levels of SYP and GAP43 in the differentiated SH-SY5Y cells by qPCR (Figure 5A). We found that glial P4-CM increased SYP and GAP43 expression by 2- and 4-fold, respectively, in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. Western blot analysis confirmed that the protein levels of SYP and GAP43 were increased by P4 as well, which was blocked by Y1036 (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Effect of glial-CM on the expression of synaptic markers. SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells were differentiated with RA for 7 days and were exposed to BDNF, DMSO-CM, or P4-CM in the presence or absence of Y1036 for 24 hours. Nontreated cultures were used as control. mRNA levels of SYP and GAP43 were determined by qPCR (A), and protein level of Pgrmc1 was determined by Western blotting (B). Representative blots were shown on the left, and the densitometry data were shown on the right. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM, n = 3 per group. #, P < .05, Y + P4 P4-CM compared with P4-CM; *, P < .05; ***, P < .001; ****, P < .0001, P4-CM compared with DMSO-CM.

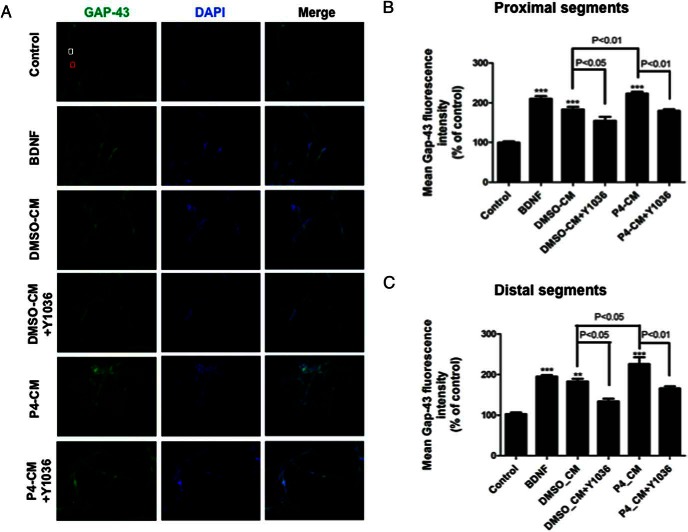

P4-CM up-regulated GAP43 expression in both proximal and distal segments of SH-SY5Y neuritis via BDNF signaling

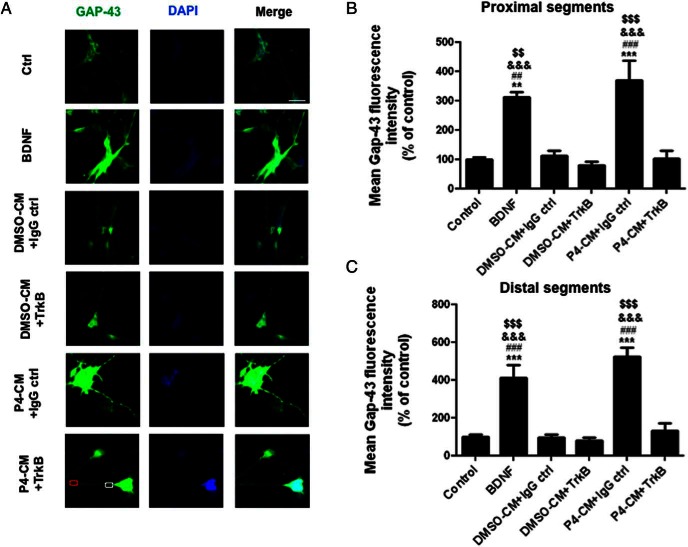

Because our qPCR and Western blotting results showed that P4-CM increased the overall expression of synaptic markers in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells at the levels of both mRNA and protein, we sought to further determine the effect of P4-CM on synaptic markers by assessing their expression at proximal and distal aspects of the neurites. This would give us an insight into any regional specificity associated with the observed effects. We found that compared with nontreated control, treatments with either BDNF or P4-CM elicited a significant increase of GAP43 fluorescence intensity in both proximal and distal neurite segments (Figures 6 and 7). Again, this effect was attenuated in the presence of Y1036, the nerve growth factor (NGF) and BDNF signaling inhibitor (Figure 6). To specifically examine the involvement of BDNF in this process, we also tested the effect of TrkB-IgG in a similar experimental setting (Figure 7). TrkB-IgG blocked the up-regulation of GAP43 expression in the neurites of differentiated SH-SY-5Y cells by P4-CM, suggesting that such an effect was indeed mediated by BDNF present in the CMs.

Figure 6.

Glial P4-CM increased GAP43 density in both proximal and distal neuritic segments of SH-SY5Y cells. A, Immunocytochemistry of SH-SY5Y cultures. Cells were treated with DMSO-CM or P4-CM in the presence or absence of Y1036 for 24 hours. 50-ng/mL BDNF was used as positive control. Cultures were stained for GAP43 (green) and DAPI (blue). The white box represents a proximal neuritic segment, and the red box indicates a distal neuritic segment. B, Quantification of GAP43 mean fluorescence intensity in proximal neuritic portions. C, Quantification of GAP43 mean fluorescence intensity in distal neuritic segments. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM, n = 3 per group; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001, compared with control. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Figure 7.

Blocking of BDNF signaling inhibited glial P4-CM-induced GAP43 density in both proximal and distal neuritic segments of SH-SY5Y cells. A, Immunocytochemistry of SH-SY5Y cultures. Cells were treated with DMSO-CM or P4-CM in the presence of human IgG control or TrkB-IgG for 24 hours. Cells treated with BDNF were used as positive control. Cultures were stained for GAP43 (green) and DAPI (blue). The white box represents a proximal neuritic segment, and the red box indicates a distal neuritic segment. B, Quantification of GAP43 mean fluorescence intensity in proximal neuritic portions. C, Quantification of GAP43 mean fluorescence intensity in distal neuritic segments. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM, n = 4 per group; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001, compared with control; ##, P < .01; ###, P < .001, compared with DMSO-CM + IgG ctrl; &&&, P < .001, compared with DMSO-CM + TrkB-IgG; $$$, P < .001, compared with P4-CM+TrkB-IgG. Scale bar, 100 μm.

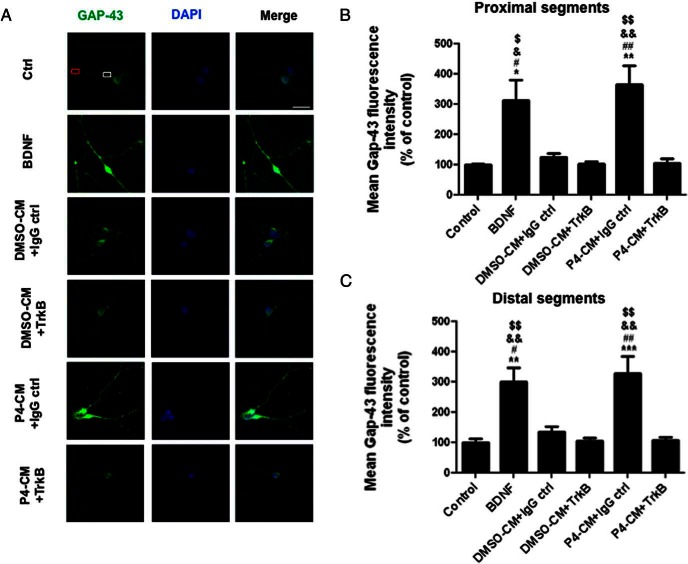

P4-CM up-regulated GAP43 expression in both proximal and distal segments of primary hippocampus neuritis via BDNF signaling

Next, we tested the GAP43 fluorescence intensity in both proximal and distal neurite segments of primary hippocampus neurons. We found that compared with the nontreated control, treatments with BDNF or P4-CM elicited a significant increase of GAP43 fluorescence intensity in both proximal and distal neurite segments, and these effects were attenuated by TrkB-IgG (Figure 8). These data were consistent with our findings in SH-SY5Y cells and further supported an involvement of BDNF in mediating the effects of glial P4-CM on neurons.

Figure 8.

Blocking of BDNF signaling inhibited glial P4-CM-induced GAP43 density in both proximal and distal neuritic segments of primary hippocampus neurons. A, Immunocytochemistry of primary neuronal cultures. Cells were treated with DMSO-CM or P4-CM in the presence of human IgG control or TrkB-IgG for 24 hours. Cells treated with BDNF were used as positive control. Cultures were stained for GAP43 (green) and DAPI (blue). The white box represents a proximal neuritic segment and the red box indicates a distal neuritic segment. B, Quantification of GAP43 mean fluorescence intensity in proximal neuritic portions. C, Quantification of GAP43 mean fluorescence intensity in distal neuritic segments. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM, n = 4 per group; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001, compared with control; #, P < .05; ##, P < .01, compared with DMSO-CM+IgG ctrl; &, P < .05; &&, P < .01, compared with DMSO-CM+TrkB-IgG; $, P < .05; $$, P < .01, compared with P4-CM+TrkB-IgG. Scale bar, 100 μm.

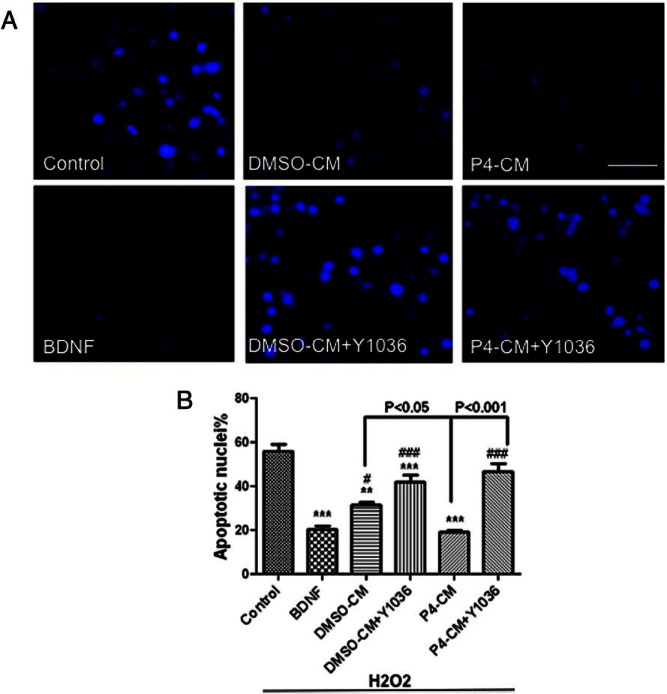

P4-CM increased neuronal survival against oxidative stress

In addition to assessing the expression of surrogate markers of neuronal function (ie, synaptogenesis), we also asked whether P4-CM has any effect on neuronal survival. We pretreated the SH-SY5Y cells with P4-CM for 24 hours, then examined the viability of SH-SY5Y cells exposed to 100μM H2O2 for another 24 hours. We found that pretreatment of SH-SY5Y cells with P4-CM significantly protected against H2O2 to a level similar to that elicited by recombinant BDNF (Figure 9). In agreement with our hypothesis that glia secret basal level BDNF to support neighboring neurons, DMSO-CM also protected the SH-SY5Y cells from H2O2, although P4 enhanced this effect further (P4-CM vs DMSO-CM, P < .05). Importantly, Y1036 abolished the effects of either DMSO-CM or P4-CM on the survival of SH-SY5Y cells. These data strongly implicate the release of neurotrophins (and their subsequent action) as the mediator of P4-CM induced neuronal survival against oxidative insult.

Figure 9.

P4-CM increased neuronal survival against oxidative stress. Differentiated SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to no-treatment (control), BDNF, DMSO-CM, or P4-CM in the presence or absence of Y1036 for 24 hours. All groups were then exposed to 100μM H2O2 for another 24 hours before the viability of SH-SY5Y cells was examined. Pretreatment of SH-SY5Y cells with P4-CM significantly protected against H2O2 to a level similar to that elicited by recombinant BDNF (A and B). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM, n = 4 per group; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001, compared with control; #, P < .05; ###, P < .001, compared with BDNF. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Discussion

Pgrmc1 is a highly conserved heme-binding protein and belongs to MAPR family (37, 38). Pgrmc1 is recognized as an important biomarker for cancer progression and as a potential target for anticancer therapies (28, 39). However, information regarding its role(s) in the brain remains limited. Munton et al showed that the expression of Pgrmc1 is broadly mapped in the brain at low levels and enriched in the postsynaptic fragment (40). Bashour and Wray (29) found that P4 decreases calcium oscillations and thereby inhibits neuronal activity through Pgrmc1 on a subpopulation of GnRH neurons in mice. With regard to glia, we discovered that Pgrmc1 is expressed on the cell surface of C6 glial cells (a model of astrocytes) as well as primary astrocytes. Functionally, we determined that P4-induced release of BDNF was mediated via Pgrmc1-dependent ERK5 signaling (26).

BDNF belongs to the family of neurotrophins (along with NGF, Neurotrophin-3, and Neurotrophin-4), which play key roles to support neuronal survival and synaptic plasticity (16, 41). Among the neurotrophins, there is significant clinical evidence to support the statement that BDNF plays a pivotal role in synaptic plasticity and cognition (17). Hippocampus-specific deletion of BDNF in adult mice impairs spatial memory (42), and exogenous BDNF rescued deficits in hippocampal long term potentiation in both homozygous and heterozygous BDNF knockout mice (43, 44). Therefore, one option for developing pharmacotherapy of neurodegenerative diseases is to focus on BDNF modulation.

To date, considerable research has been conducted in understanding the etiology of neurodegenerative diseases from the standpoint of neuronal dysfunction, with a relatively smaller, but growing, body of literature that implicates glia in the pathogenesis and/or progression of these diseases. We previously reported that P4 not only increases the expression of BDNF in cerebral cortical explants but that the protective effects of P4 are mediated by neurotrophin signaling (17). Given the critical roles that BDNF plays during aging and in neurodegenerative diseases such as AD, our data elucidated a novel mechanism for glia to affect neuronal survival and functions via secreting soluble factors such as BDNF and thus may help develop more efficient therapeutic interventions for neurodegenerative diseases.

As mentioned in the Results, the pro- and mature form of neurotrophins can often exert opposite effects on cell viability. As such, we investigated whether the previously described increase in BDNF release was attributed to preferential release of one or both forms of BDNF. Our data revealed that P4 increases the ratio of mature to pro-BDNF within the released pool of BDNF from glia (Figure 1A). Further, this P4-induced increase in the ratio of mature to pro-BDNF was dependent on Pgrmc1 (Figure 1B).

In an effort to address the hypothesis that the neuroprotective effects of P4 may be mediated, at least in part, through astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factors, we assessed surrogate markers of synaptic structure/function and cell viability in neurons exposed to P4-CMs. We found that such CMs not only increase the expression of synaptic markers, such as GAP43, but also protected the cells from a cytotoxic insult. Although there was a trend noted for the effect of P4-CM to induce the transcription of the presynaptic marker, SYP, there was no effect on its protein levels, at least at the time point evaluated in these studies. This difference between changes in pre- vs postsynaptic markers may be consistent with the report by Miyata et al (45), which demonstrated an inverse correlation between GAP43 protein expression level vs presynaptic terminal markers in immature synapses of rat hippocampal neurons (27).

Previous studies have shown that all-trans RA treatment of SH-SY5Y cells triggered the expression of functional TrkB (receptor for BDNF) but not TrkA (receptor for NGF) (36). Because Y1036 is known to bind only to BDNF and NGF (thereby preventing the interaction with their cognate receptor), our data showing that Y1036 attenuated P4-CM-induced GAP43 expression in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells strongly point to a role of BDNF in mediating this process. Furthermore, we chose to examine specific regions of neurons where markers of synaptic functions/structure were affected by P4-CM. GAP43 has been shown to localize in cellular membranes of axons and growth cones (45). By focusing on the cellular processes (eg, neurites), we found that treatments with BDNF (used as the positive control) or P4-CM elicited a significant increase in GAP43 expression in both proximal and distal neurite segments compared with the nontreated control group (Figure 7). In order to more specifically block the BDNF signaling, we then tested the effect of TrkB-IgG in glial P4-CM-treated neuronal cultures. We examined both the differentiated SH-SY5Y cells as well as the mouse primary hippocampal neurons as 2 complimentary neuron models. In both cell types, P4-CM + control IgG induced significant increases in the GAP43 fluorescence intensity in proximal and distal segments compared with DMSO-CM + control IgG, which were blocked by the TrkB-IgG (Figures 8 and 9). These observations demonstrated that the P4-CM-induced increase in synaptic marker expression occurred at expected and appropriate locations. These data further support our conclusion that the up-regulation of GAP43 expression in neurites was mediated by BDNF available in the CMs.

Finally, we sought to determine whether the effects of P4-CM on markers of neuronal function would translate into actual cytoprotection. In this regard, we found that P4-CM did indeed increased neuron survival challenged with an oxidative insult (Figure 9). Furthermore, the neuroprotection effect of glial P4-CM was abolished by Y1036, again supporting the model that the protective effects of P4 may be mediated by glial-derived neurotrophic factors.

In summary, our data support the critical role of Pgrmc1/BDNF signaling in mediating glia-neuron cross talk. In addition, Pgrmc1 may play a critical role in mediating a complicated cross talk between all the brain cell types and implicate glial Pgrmc1 as a potential therapeutic target for treating neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from the American Federation of Aging Research and the American Heart Association (C.S.), National Institutes of Health National Institute of Aging Grants AG022550 and AG027956, the Alzheimer's Association, and the Texas Garvey Foundation (M.S.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AD

- Alzheimer's disease

- BDNF

- brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CM

- conditioned medium

- Ct

- cycle threshold

- DIV

- day in vitro

- DMSO

- dimethylsulfoxide

- DMSO-CM

- DMSO condition medium

- GAP43

- Growth Associated Protein 43

- GAPDH

- Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- MAPR

- membrane-associated P4 receptor

- NGF

- nerve growth factor

- P4

- progesterone

- P4-CM

- CM from P4-treated astrocytes

- Pgrmc1

- P4 receptor membrane component 1

- RA

- retinoic acid

- SYP

- synaptophysin

- TBI

- traumatic brain injury

- Trk

- tropomysin-related kinase.

References

- 1. Roof RL, Hall ED. Gender differences in acute CNS trauma and stroke: neuroprotective effects of estrogen and progesterone. J Neurotrauma. 2000;17(5):367–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Atif F, Yousuf S, Sayeed I, Ishrat T, Hua F, Stein DG. Combination treatment with progesterone and vitamin D hormone is more effective than monotherapy in ischemic stroke: the role of BDNF/TrkB/Erk1/2 signaling in neuroprotection. Neuropharmacology. 2013;67:78–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu A, Margaill I, Zhang S, et al. Progesterone receptors: a key for neuroprotection in experimental stroke. Endocrinology. 2012;153(8):3747–3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wali B, Sayeed I, Stein DG. Improved behavioral outcomes after progesterone administration in aged male rats with traumatic brain injury. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2011;29(1):61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wright DW, Kellermann AL, Hertzberg VS, et al. ProTECT: a randomized clinical trial of progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(4):391–402, 402.e1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vandromme M, Melton SM, Kerby JD. Progesterone in traumatic brain injury: time to move on to phase III trials. Crit Care. 2008;12(3):153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xiao G, Wei J, Yan W, Wang W, Lu Z. Improved outcomes from the administration of progesterone for patients with acute severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2008;12(2):R61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Junpeng M, Huang S, Qin S. Progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(1):CD008409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lewis MC, Orr PT, Frick KM. Differential effects of acute progesterone administration on spatial and object memory in middle-aged and aged female C57BL/6 mice. Horm Behav. 2008;54(3):455–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Frye CA, Walf AA. Progesterone enhances performance of aged mice in cortical or hippocampal tasks. Neurosci Lett. 2008;437(2):116–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wright DW, Yeatts SD, Silbergleit R, et al. Very early administration of progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2457–2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Hyman BT. Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011;1(1):a006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barha CK, Ishrat T, Epp JR, Galea LA, Stein DG. Progesterone treatment normalizes the levels of cell proliferation and cell death in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus after traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2011;231(1):72–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhao Y, Wang J, Liu C, Jiang C, Zhao C, Zhu Z. Progesterone influences postischemic synaptogenesis in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in rats. Synapse. 2011;65(9):880–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cohen S, Greenberg ME. Communication between the synapse and the nucleus in neuronal development, plasticity, and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:183–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lu Y, Christian K, Lu B. BDNF: a key regulator for protein synthesis-dependent LTP and long-term memory? Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;89(3):312–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Causing CG, Gloster A, Aloyz R, et al. Synaptic innervation density is regulated by neuron-derived BDNF. Neuron. 1997;18(2):257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pruginin-Bluger M, Shelton DL, Kalcheim C. A paracrine effect for neuron-derived BDNF in development of dorsal root ganglia: stimulation of Schwann cell myelin protein expression by glial cells. Mech Dev. 1997;61(1–2):99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Matsumoto T, Rauskolb S, Polack M, et al. Biosynthesis and processing of endogenous BDNF: CNS neurons store and secrete BDNF, not pro-BDNF. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(2):131–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lu B, Pang PT, Woo NH. The yin and yang of neurotrophin action. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(8):603–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Minichiello L. TrkB signalling pathways in LTP and learning. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(12):850–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yoshii A, Constantine-Paton M. Postsynaptic BDNF-TrkB signaling in synapse maturation, plasticity, and disease. Dev Neurobiol. 2010;70(5):304–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Phillips HS, Hains JM, Armanini M, Laramee GR, Johnson SA, Winslow JW. BDNF mRNA is decreased in the hippocampus of individuals with Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 1991;7(5):695–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Connor B, Young D, Yan Q, Faull RL, Synek B, Dragunow M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is reduced in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1997;49(1–2):71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hock C, Heese K, Müller-Spahn F, Hulette C, Rosenberg C, Otten U. Decreased trkA neurotrophin receptor expression in the parietal cortex of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 1998;241(2–3):151–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Su C, Cunningham RL, Rybalchenko N, Singh M. Progesterone increases the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor from glia via progesterone receptor membrane component 1 (Pgrmc1)-dependent ERK5 signaling. Endocrinology. 2012;153(9):4389–4400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peluso JJ, Liu X, Gawkowska A, Lodde V, Wu CA. Progesterone inhibits apoptosis in part by PGRMC1-regulated gene expression. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;320(1–2):153–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Intlekofer KA, Petersen SL. Distribution of mRNAs encoding classical progestin receptor, progesterone membrane components 1 and 2, serpine mRNA binding protein 1, and progestin and ADIPOQ receptor family members 7 and 8 in rat forebrain. Neuroscience. 2011;172:55–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bashour NM, Wray S. Progesterone directly and rapidly inhibits GnRH neuronal activity via progesterone receptor membrane component 1. Endocrinology. 2012;153(9):4457–4469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bali N, Arimoto JM, Iwata N, et al. Differential responses of progesterone receptor membrane component-1 (Pgrmc1) and the classical progesterone receptor (Pgr) to 17β-estradiol and progesterone in hippocampal subregions that support synaptic remodeling and neurogenesis. Endocrinology. 2012;153(2):759–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guennoun R, Meffre D, Labombarda F, et al. The membrane-associated progesterone-binding protein 25-Dx: expression, cellular localization and up-regulation after brain and spinal cord injuries. Brain Res Rev. 2008;57(2):493–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sarkar SN, Huang RQ, Logan SM, Yi KD, Dillon GH, Simpkins JW. Estrogens directly potentiate neuronal L-type Ca2+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(39):15148–15153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Singh M, Sétáló G, Jr, Guan X, Warren M, Toran-Allerand CD. Estrogen-induced activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in cerebral cortical explants: convergence of estrogen and neurotrophin signaling pathways. J Neurosci. 1999;19(4):1179–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stroemer RP, Kent TA, Hulsebosch CE. Increase in synaptophysin immunoreactivity following cortical infarction. Neurosci Lett. 1992;147(1):21–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chamniansawat S, Chongthammakun S. Estrogen stimulates activity-regulated cytoskeleton associated protein (Arc) expression via the MAPK- and PI-3K-dependent pathways in SH-SY5Y cells. Neurosci Lett. 2009;452(2):130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Encinas M, Iglesias M, Llecha N, Comella JX. Extracellular-regulated kinases and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase are involved in brain-derived neurotrophic factor-mediated survival and neuritogenesis of the neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y. J Neurochem. 1999;73(4):1409–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rohe HJ, Ahmed IS, Twist KE, Craven RJ. PGRMC1 (progesterone receptor membrane component 1): a targetable protein with multiple functions in steroid signaling, P450 activation and drug binding. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;121(1):14–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ahmed IS, Rohe HJ, Twist KE, Mattingly MN, Craven RJ. Progesterone receptor membrane component 1 (Pgrmc1): a heme-1 domain protein that promotes tumorigenesis and is inhibited by a small molecule. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;333(2):564–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Munton RP, Tweedie-Cullen R, Livingstone-Zatchej M, et al. Qualitative and quantitative analyses of protein phosphorylation in naive and stimulated mouse synaptosomal preparations. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6(2):283–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Murer MG, Yan Q, Raisman-Vozari R. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the control human brain, and in Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;63(1):71–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Heldt SA, Stanek L, Chhatwal JP, Ressler KJ. Hippocampus-specific deletion of BDNF in adult mice impairs spatial memory and extinction of aversive memories. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12(7):656–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Diamond DM, Park CR, Campbell AM, Woodson JC. Competitive interactions between endogenous LTD and LTP in the hippocampus underlie the storage of emotional memories and stress-induced amnesia. Hippocampus. 2005;15(8):1006–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Patterson SL, Abel T, Deuel TA, Martin KC, Rose JC, Kandel ER. Recombinant BDNF rescues deficits in basal synaptic transmission and hippocampal LTP in BDNF knockout mice. Neuron. 1996;16(6):1137–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fumagalli F, Racagni G, Riva MA. The expanding role of BDNF: a therapeutic target for Alzheimer's disease? Pharmacogenomics J. 2006;6(1):8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Morita S, Miyata S. Synaptic localization of growth-associated protein 43 in cultured hippocampal neurons during synaptogenesis. Cell Biochem Funct. 2013;31(5):400–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]