Keywords: nerve regeneration, tree shrews, hippocampus, neural stem cells, cell proliferation, nerve growth factor, neurosphere, embryo, cell number, cell therapy, in vitro, neural regeneration

Abstract

Neural stem cells promote neuronal regeneration and repair of brain tissue after injury, but have limited resources and proliferative ability in vivo. We hypothesized that nerve growth factor would promote in vitro proliferation of neural stem cells derived from the tree shrews, a primate-like mammal that has been proposed as an alternative to primates in biomedical translational research. We cultured neural stem cells from the hippocampus of tree shrews at embryonic day 38, and added nerve growth factor (100 μg/L) to the culture medium. Neural stem cells from the hippocampus of tree shrews cultured without nerve growth factor were used as controls. After 3 days, fluorescence microscopy after DAPI and nestin staining revealed that the number of neurospheres and DAPI/nestin-positive cells was markedly greater in the nerve growth factor-treated cells than in control cells. These findings demonstrate that nerve growth factor promotes the proliferation of neural stem cells derived from tree shrews.

Introduction

Neural stem cells (NSCs) are multipotent, self-renewing cells in the mammalian central nervous system, and promote neuronal regeneration and nervous tissue repair (Anderson and Michelsohn, 1989; Gould and Gross, 2002; Gritti et al., 2002). In addition to being used as a vector for gene therapy against nervous system diseases, NSCs can be induced to differentiate into neurons and promote the repair of brain tissue (Aleksandrova et al., 2005; Eslamboli et al., 2005).

NSCs derived from rats can facilitate the recovery of neuronal injury; however, when implanted in vivo they show limited ability to proliferate and differentiate (Tran et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2015). Changes in the culture environment influence the growth and metabolism of NSCs, and three-dimensional cell vectors can facilitate growth of NSCs in vitro (Song et al., 2014). Therefore, it is necessary to isolate NSCs and make them proliferate well in vitro first. The environment may affect the biological features of NSCs (Laywell et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2003). Suitable conditions and drugs that can promote the proliferation of NSCs in the brain will pave a new way for rehabilitative therapy of nervous system diseases.

Nerve growth factor (NGF) plays a crucial role in the proliferation and development of stem cells (Xu et al., 2012), regulating normal cell development and promoting neuronal survival and regeneration (Benoit et al., 2001). However, it remains unknown whether NGF can promote the proliferation of NSCs derived from primates. The tree shrew is a small, arboreal mammal from the family Tupaiidae, which lives in the tropics and subtropics. Genomically, metabolically and anatomically, tree shrews are relatively closer to humans than rodents; coupled with their small size and ease of breeding (Janecka et al., 2007; Fan et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2013), they are a promising convenient and low-cost substitute for rodents and primates in animal studies. They have already been widely used in studies of physiology, anatomy, virology, neuropsychiatry, neural development, and nervous system diseases (Wang et al., 2011, 2012; Ruan et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2014). NSCs derived from the tree shrew could provide a suitable cell model for studying human diseases that may require stem cell therapy.

Therefore, in the present study, we explored the conditions for the culture of tree shrew-derived NSCs, and studied the effect of NGF on their growth.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Six clean, pregnant female tree shrews, at 38 days of gestation and weighing 170 g, were provided by the Experimental Animal Center of Kunming Medical University, China (Animal license No. SYXK (Dian) K2015-0002). Tree shrews were housed in individual cages under a 12 hour light/dark cycle and in a dry and ventilated room at 23–25°C, with free access to food and water. All surgery was performed under anesthesia, and all efforts were made to minimize pain and distress in the experimental animals. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the United States National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Publication No. 85-23, revised 1986). Animal care and all experimental protocols were approved by the guidelines of the Institutional Medical Experimental Animal Care Committee of Sichuan University, West China Hospital, China.

Sample harvest

The animals were sacrificed after intraperitoneal anesthesia with 3.6% chloral hydrate (1 mL/100 g) (SG1019; TongYao Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). On a superclean bench, the fetuses were extracted under sterile conditions, and placed into culture dishes containing D-Hank's solution. The skulls were carefully dissected, and the brains removed and kept in pre-cooled phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Under an anatomic microscope, the meninges, olfactory bulb, cerebellum and brain stem were removed to expose the hippocampi. These were harvested and washed twice with pre-cooled PBS.

Preparation of cell suspension

Hippocampal tissue was kept in pre-cooled Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F12 (1:1; Gibco, New York, NY, USA). The tissue was cut into 1 mm3 blocks using microscissors, and transferred into centrifuge tubes. Subsequently, all samples were digested with 0.25% trypsin (1:250; Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA) for 20 minutes, treated with DMEM/F12 to stop the digestion, and then centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 minutes. Supernatant was discarded, 100 mL DMEM/F12 (1:1; Gibco) was added to the cell suspension, with 2 mL B27 (Gibco), 2 mM glutamine, 2 μg basic fibroblast growth factor (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) 1% N2 (Gibco), 10,000 U/L penicillin and 10 mg/L streptomycin. The cell suspension was then harvested.

Cell inoculation

The density of the cell suspension was adjusted to 5 × 105/mL. The cells were placed in an incubator (Thermo, Marietta, OH, USA) containing 5% CO2 at 37°C for 48 hours and half of the culture medium was replaced every other day for 7 days. After 2 days in culture, the cultures were centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 minutes, the supernatant was discarded; this process was repeated two more times. All samples were then digested with 1 mL 0.25% trypsin at room temperature for 15 minutes and centrifuged again at 800 × g for 5 minutes. Stem cell culture medium was added and the culture plates were inoculated. Cells were cultured in an incubator (Thermo) at 5% CO2 and 37°C.

NSC subculturing

NSCs were subcultured once every seven days when the neurospheres reached 100 μm in diameter. The NSC suspension was collected into 15 mL of sterile centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was discarded. The cells were resuspended in the DMEM/F12 medium containing 20 ng/mL fibroblast growth factor and 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor. Finally, the cell suspension was mixed gently and incubated at 37°C in 25 mL culture bottles at a density of 1.5–2.5 × 106/mL.

NSC identification

The third passage of NSCs was digested with 0.25% trypsin, and the digestion was terminated with culture medium containing the serum. The cell suspension was dropped onto the cover slips for 3 days of incubation. Nestin immunocytochemistry (1:200; Chemicon, Lansing, NC, USA) was used to identify the cultured cells as NSCs. Red-staining nestin-immunoreactivity showed that the red color mainly existed in the cytoplasm. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used to label nuclei, which appeared blue. Together, this confirmed that the cultured cells were NSCs.

NGF administration and morphology

Cultured NSCs were divided into two groups: NGF-induced (NGF-NSC), and control. NGF (100 μg/L; Gibco) was added to DMEM/F12 culture medium in the NGF-NSC group but not the control group. After 3 days of incubation, in vitro samples were prepared in 6-well plates. To determine the number of neurospheres and the NSC area, cells were collected from five fields of each well, and photographed with a fluorescent microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) at 200× magnification. Neurosphere number and NSC area were calculated with Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (MediaCybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA). The neurosphere count was processed by three experimenters blinded to the type of treatment. The mean of their counts was the final result. For NSC area, we used the average pixels method. The thresholds for NSC staining intensity were determined after all images were acquired. The total pixel count per image field (300 × 300) was measured. Average pixel count was calculated as the ratio of total pixels per image field relative to the total area (average pixels = sum pixels / sum area).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD, and were analyzed using SPSS 18.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Student's t-test with two-tailed distribution was used to compare means. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Growth of NSCs derived from tree shrews

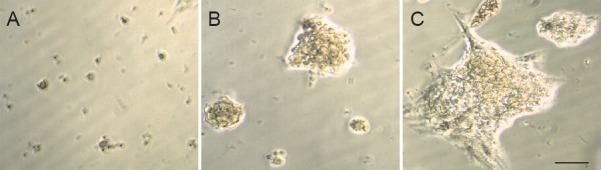

At 12 hours of primary culture, small, transparent, round or oval single cells were mainly observed in the suspension. Most cells had no processes and good refraction (Figure 1A). After 2 days in culture, tens of cells aggregated to form neurospheres that gradually enlarged over time (Figure 1B). Suspended growth of surviving neurospheres was observed until 7 days in culture (Figure 1C). The passaged neurospheres grew further in number and volume, and became spheres that consisted of tens to hundreds of cells. After subculturing, single cells and small cell clumps could be seen. Some cells died, and others proceeded to the cleavage phase.

Figure 1.

Dynamic temporal changes of growth of cultured tree shrew NSCs under the light field of the immunofluorescent microscope.

(A) Cultured NSCs at 12 hours were mainly single cells, small and transparent, and round or oval in shape. (B) Tens of cells aggregated to form neurospheres after 2 days in culture. (C) Neurospheres enlarged over time; the surviving neurospheres showed suspended growth after 7 days in culture. NSCs: Neural stem cells. Scale bar: 100 μm.

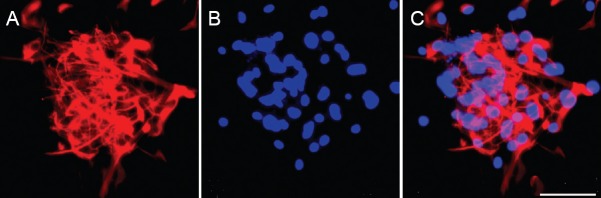

Identification of NSCs

Nestin immunoreactivity was present in the neurospheres, mainly in the cytoplasm (Figure 2A). DAPI labelling was mainly distributed in the nuclei (Figure 2B). Nestin- and DAPI-positive staining co-existed in the cultured NSCs (Figure 2C), indicating that we had successfully isolated NSCs from tree shrews. This provided a good foundation for the subsequent experiments.

Figure 2.

Identification of third-passage tree shrew NSCs after 3 days in culture (immunofluorescence staining).

(A) Neurospheres were positive for the NSC marker nestin (red fluorescence). (B) DAPI nuclear staining (blue fluorescence). (C) Merged image for nestin and DAPI, showing the cultured NSCs. NSCs: Neural stem cells; DAPI: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Scale bar: 50 μm.

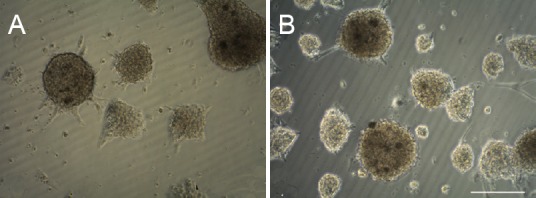

Role of NGF in the morphology of NSCs

At 3 days of culture post NGF administration, single cells and small cell clumps were observed in the cultured NSCs. Notably, some neurospheres aggregated with stronger refraction over time, and the number of neurospheres was higher in the NGF-NSC group than in the control group (Figure 3A, B).

Figure 3.

Morphological changes of NSCs at 3 days in culture under the light field of immunofluorescent microscope.

(A) Control group. Single cell and small cell clumps were visible in cultured control NSCs. (B) NGF-NSC group. Aggregation of multiple neurospheres was observed, with strong refraction. NSCs: Neural stem cells; NGF: nerve growth factor. Scale bar: 100 μm.

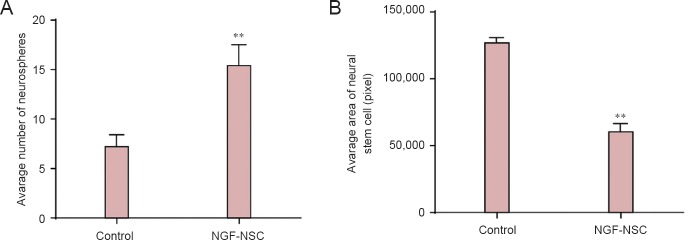

NGF effects on the proliferation of neurospheres

At 3 days of culture, the number of neurospheres was significantly greater in the NGF-NSC group than in the control group (P < 0.01; Figure 4A). However, the average area of NSCs in the first passage of cells was lower in the NGF-NSC group than in the control group (P < 0.01; Figure 4B). This suggested that NGF plays a crucial role in NSC proliferation and promotes the proliferation of neurospheres. New NSCs had a relatively small area, however.

Figure 4.

Effects of NGF on proliferation in cultured tree shrew-derived NSCs at 3 days.

(A) Number of neurospheres in 6-well plates using an immunofluorescent microscope at 200× magnification. (B) Cell area in 6-well plates using an immunofluorescent microscope at 200× magnification. **P < 0.01, vs. control group (mean ± SD, n = 5, Student's t-test). NGF: Nerve growth factor; NSC: neural stem cells.

Discussion

In this study, we found that primary cultured NSCs derived from tree shrews proliferated successfully, from single cells into tens, and aggregated to form neurospheres under our culture conditions. Moreover, following NGF administration, the number of neurospheres in the cultured NSCs was significantly greater, but the average cell area was markedly smaller, than in control cells. These findings show that NGF effectively promoted the growth of tree shrew NSCs in vitro, and provide new evidence to demonstrate the biological characteristics of NSCs in these primate-like mammals.

Characteristics of NSCs from embryonic tree shrew in vitro

Nestin is used as a marker of NSCs, because it is associated with the survival, renewal and mitogen-stimulated proliferation of neural progenitor cells (Yuan et al., 2015). In the present study, red nestin fluorescence confirmed that NSCs from the tree shrew had been successfully isolated and cultured. In addition, the number of primary cultured NSCs from tree shrews increased. Tens of cells aggregated to form neurospheres, which enlarged over time. These results suggest that the tree shrew-derived NSCs we cultured had the ability to self-renew and proliferate.

NSC proliferation induced by NGF

Following NGF induction, the number of neurospheres was significantly greater than without NGF, and most new neurospheres consisted of small cells. This suggests that NGF induced proliferation in cultured tree shrew NSCs. However, the proliferative ability of NSCs is limited and the molecular mechanism of NSC proliferation and differentiation is complex. It is widely accepted that NSC proliferation and differentiation are related to the internal cellular environment (Kalyani et al., 1997; Liu et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2002; Gao and Zheng, 2013). In rodent NSCs, various factors influence the quality of the cultured cells, including sample harvesting time, cell density, subculturing time, cytokines, and serum concentration (Li et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2011; Marei et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2013). During NSC culture, apart from essential basic culture medium, some growth factors need to be added. Without sufficient growth factor concentration, cell numbers in culture will not increase (Marei et al., 2013). NGF, an important neurotrophic factor, plays a crucial role in the division and proliferation of nerve cells (Doering and Snydeer, 2000; Wachs et al., 2003; Oliveira et al., 2015), and in axonal growth and cellular network formation (Guo et al., 2013). Therefore, when the nervous system is injured, NGF is involved in the growth of most neurons, especially in anti-apoptosis and promoting recovery of neural function (Carito et al., 2015; Turney et al., 2015). However, these previous studies did not address the role of NGF in the proliferation of tree shrew-derived NSCs. To our knowledge, we are the first to address this issue.

Future application in translational medicine

NSC transplantation may be a strategy to promote recovery from central nervous system diseases in translational research (Piltti et al., 2013; Nizzardo et al., 2014). Establishing non-human primate models of human diseases is an efficient way to narrow the large gap between basic studies and clinical medicine (Wang et al., 2013). Tree shrews are advantageous as they are relatively closer to humans and primates than rodents (Fan et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2013). It is therefore important to study the effects of NGF in NSCs isolated from the tree shrew in vitro. The limited ability of NSCs implanted in vivo to proliferate and differentiate into neurons (Tran et al., 2010) means it is important to find an agent that will increase the number of NSCs in culture. From our study, we conclude that NGF promotes the proliferation of tree shrew-derived NSCs, and has the potential to increase the number of cultured NSCs for later transplantation.

The mechanisms by which NGF promotes NSC proliferation are complex (Van Kanegan and Strack, 2009; Yuan et al., 2013) and will be addressed in our future experiments.

In summary, we successfully established an in vitro cultured tree shrew NSC model. We observed the morphological changes in NSC cultures in vitro, and explored the effect of NGF. We showed that our culture conditions for tree shrew-derived NSCs were successful, and also that NGF is effective for their growth. Our study provides valuable insight into the role of NGF in NSCs derived from the tree shrew, a promising alternative to primates in translational research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xin-fu Zhou from University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA, Australia and Qing-jie Xia from West China Hospital, Sichuan University in China for the suggestion on the paper.

Footnotes

Funding: This research was supported by a grant from the National Key Technology Research and Development Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, No. 2014BAI01B00.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Plagiarism check: Plagiarism check: This paper was screened twice using Cross-Check to verify originality before publication.

Peer review: This paper was double-blinded and stringently reviewed by international expert reviewers.

Copyedited by Slone-Murphy J, Frenchman B, Wang J, Qiu Y, Li CH, Song LP, Zhao M

References

- Aleksandrova MA, Podgornyi OV, Marei MV, Poltavtseva RA, Tsitrin EB, Gulyaev DV, Cherkasova LV, Revishchin AV, Korochkin LI, Khrushchov NG, and Sukhikh GN. Characteristics of human neural stem cells in vitro and after transplantation into rat brain. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2005;139:114–120. doi: 10.1007/s10517-005-0227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DJ, Michelsohn A. Role of glucocorticoids in the chromaffin-neuron developmental decision. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1989;7:475–487. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(89)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit BO, Savarese T, Joly M, Engstrom CM, Pang L, Reilly J, Recht LD, Ross AH, Quesenberry PJ. Neurotrophin channeling of neural progenitor cell differentiation. J Neurobiol. 2011;46:265–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carito V, Nicolò S, Fiore M, Maccarone M, Tirassa P. Ocular nerve growth factor administration (oNGF) affects disease severity and inflammatory response in the brain of rats with experimental allergic encephalitis (EAE) Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2015;29:1–8. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2015-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MM, Zhao GW, He P, Jiang ZL, Xi X, Xu SH, Ma DM, Wang Y, Li YC, Wang GH. Improvement in the neural stem cell proliferation in rats treated with modified “Shengyu” decoction may contribute to the neurorestoration. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;165:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doering LC, Snydeer EY. Cholinergic expression by a neural stem cell line grafted to the adult medial septum/diagonal band complex. Neurosci Res. 2000;61:597–604. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000915)61:6<597::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eslamboli A, Georgievska B, Ridley RM, Baker HF, Muzyczka N, Burger C, Mandel RJ, Annett L, Kirik D. Continuous low-level glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor delivery using recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors provides neuroprotection and induces behavioral recovery in a primate model of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:769–777. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4421-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Huang ZY, Cao CC, Chen CS, Chen YX, Fan DD, He J, Hou HL, Hu L, Hu XT, Jiang XT, Lai R, Lang YS, Liang B, Liao SG, Mu D, Ma YY, Niu YY, Sun XQ, Xia JQ, et al. Genome of the Chinese tree shrew. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1426. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao MY, Zheng QX. The research progress of neural stem cells differentiated regulation. Guowai Yixue: Binglixue yu Linchuang Fence. 2003;23:155–157. [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Gross CG. Neuron genes is in adult mammals some progress and problem. J Neurosci. 2002;22:619–623. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00619.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritti A, Bonfanti L, Doetsch F, Caille I, Alvarez-Buylla A, Lim DA, Galli R, Verdugo JM, Herrera DG, Vescovi AL. Multipotent neural stem cells reside into the rostral extension and olfactory bulb of adult rodents. J Neurosci. 2002;22:437–445. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-02-00437.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Wang J, Liang C, Yan J, Wang Y, Liu G, Jiang Z, Zhang L, Wang X, Wang Y, Zhou X, Liao H. proNGF inhibits proliferation and oligodendrogenesis of postnatal hippocampal neural stem/progenitor cells through p75NTR in vitro. Stem Cell Res. 2013;11:874–887. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janecka JE, Miller W, Pringle TH, Wiens F, Zitzmann A, Helgen KM, Springer MS, Murphy WJ. Molecular and genomic data identify the closest living relative of primates. Science. 2007;318:792–794. doi: 10.1126/science.1147555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyani A, Hobson K, Rao MS Nieto-Estévez V. Neuroepithlialstem cells from the embryonic spinal cord: isolation, characterization and clonal analysis. Dev Biol. 1997;186:202–223. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laywell ED, Rakic P, Kukekov VG, Holland EC, Steindler DA. Identification of a multipotent astrocytic stem cell in the immature and adult mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13883–13888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250471697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Himes BT, Solowska J, Moul J, Chow SY, Park KI, Tessler A, Murray M, Snyder EY, Fischer I. Intraspinal delivery of neurotrophin-3 using neural stem cells genetically modified by recom binantretrovirus. Exp Neurol. 1999;158:9–26. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marei HE, Althani A, Afifi N, Abd-Elmaksoud A, Bernardini C, Michetti F, Barba M, Pescatori M, Maira G, Paldino E, Manni L, Casalbore P, Cenciarelli C. Over-expression of hNGF in adult human olfactory bulb neural stem cells promotes cell growth and oligodendrocytic differentiation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto-Estévez V, Pignatelli J, Araúzo-Bravo MJ, Hurtado-Chong A, Vicario-Abejón C. A global transcriptome analysis reveals molecular hallmarks of neural stem cell death, survival, and differentiation in response to partial FGF-2 and EGF deprivation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nizzardo M, Simone C, Rizzo F, Ruggieri M, Salani S, Riboldi G, Faravelli I, Zanetta C, Bresolin N, Comi GP, Corti S. Minimally invasive transplantation of iPSC-derived ALDHhiSSCloVLA4+ neural stem cells effectively improves the phenotype of an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis model. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:342–354. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira SL, Trujillo CA, Negraes PD, Ulrich H. Effects of ATP and NGF on proliferation and migration of neural precursor cells. Neurochem Res. 2015;40:1849–1857. doi: 10.1007/s11064-015-1674-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piltti KM, Salazar DL, Uchida N, Cummings BJ, Anderson AJ. Safety of Human Neural Stem Cell Transplantation in Chronic Spinal Cord Injury. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2013;2:961–974. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan P, Yang C, Su J, Cao J, Ou C, Luo C, Tang Y, Wang Q, Yang F, Shi J, Lu X, Zhu L, Qin H, Sun W, Lao Y, Li Y. Histopathological changes in the liver of tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri chinensis) persistently infected with hepatitis B virus. Virol J. 2013;10:333. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song K, Ge D, Guan S, Sun C, Ma X, Liu T. Mass transfer analysis of growth and substance metabolism of NSCs cultured in collagen-based scaffold in vitro. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;174:2114–2130. doi: 10.1007/s12010-014-1165-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song K, Yang Y, Li S, Wu M, Wu Y, Lim M, Liu T. In vitro culture and oxygen consumption of NSCs in size-controlled neurospheres of Ca-alginate/gelatin microbead. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2014;40:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2014.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran KD, Ho A, Jan dial R. Stem cell transplantation methods. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;671:41–57. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5819-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turney SG, Ahmed M, Chandrasekar I, Wysolmerski RB, Goeckeler ZM, Rioux RM4, Whitesides GM, Bridgman PC. Nerve growth factor stimulates axon outgrowth through negative regulation of growth cone actomyosin restraint of microtubule advance. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;27:500–517. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-09-0636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kanegan MJ, Strack S. The protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunits B’ beta and B’delta mediate sustained TrkA neurotrophin receptor autophosphorylation and neuronal differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:662–674. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01242-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachs FP, Couillard-Despres S, Engelhardt M, Wilhelm D, Ploetz S, Vroemen M, Kaesbauer J, Uyanik G, Klucken J, Karl C, Tebbing J, Svendsen C, Weidner N, Kuhn HG, Winkler J, Aigner L. High efficacy of clonal growth and expansion of adult neural stem cells. Lab Invest. 2003;83:949–962. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000075556.74231.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Xu XL, Ding ZY, Mao RR, Zhou QX, Lü LB, Wang LP, Wang S, Zhang C, Xu L, Yang YX. Basal physiological parameters in domesticated tree shrews (Tupaia belangeri chinensis) Dongwuxue Yanjiu. 2013;34:E69–74. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1141.2013.E02E69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhou QX, Tian M, Yang YX, and Xu L. Tree shrew models: a chronic social defeat model of depression and a one-trial captive conditioning model of learning and memory. Dongwuxue Yanjiu. 2011;32:24–30. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1141.2011.01024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Yang C, Su JJ, Cao J, Ou C, Yang F, Zhang JJ, Shi JL, Wang DP, Wang XJ, Wan J, Ruan P, Li Y. Factors influencing long-term hepatitis B virus infection of the tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri chinensis) as an in vivo model of chronic hepatitis. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Zazhi. 2012;20:654–658. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, Gao Z, He W, Ma Y, Feng X, Cai T, Lu F, Liu L, and Li W. microRNA expression in hepatitis B virus infected primary tree shrew hepatocytes and the independence of intracellular miR-122 level for de novo HBV infection in culture. Virology. 2014;448:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Fan Y, Jiang XL, Yao YG. Molecular evidence on the phylogenetic position of tree shrews. Zool Res. 2013;2:70–76. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1141.2013.02070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Zhou S, Feng GY, Zhang LP, Zhao DM, Sun Y, Liu Q, Huang F. Neural stem cells enhance nerve regeneration after sciatic nerve injury in rats. Mol Neurobiol. 2012;46:265–274. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang WG. The sino-burmese tree colts guangxi said Burma in the monkey brain stereotaxic atlas. Nanning: Guangxi Science and Technology Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Huang G, Xiao Z, Lin L, Han T. Overexpression of beta-NGF promotes differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into neurons through regulation of AKT and MAPK pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;383:201–211. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1768-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan LL, Guan YJ, Ma DD, Du HM. Optimal concentration and time window for proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells from embryonic cerebral cortex: 5% oxygen preconditioning for 72 hours. Neural Regen Res. 2015;10:1516–1522. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.165526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang PB, Li WS, Gao M, Li L, Wang N, Lei S, Lv HX, Chen XL, Liu Y. Culture and identification of neural stem cells from mouse embryos. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2011;13:244–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Li X, Wu J, Wang Z, Xu H, Yang D. Isolation, cultivation and identification of stem cells from cerebral cortex of mouse embryo. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2002;82:832–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Lin LB, Ji XT, Fei Z, Wu JW, Li X. Exogenous nitric oxide inhibits the proliferation of mouse neural progenitor cells. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2003;83:1259–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]