Abstract

Nusinersen (ISIS-SMNRx or ISIS 396443) is an antisense oligonucleotide drug administered intrathecally to treat spinal muscular atrophy. We summarize lumbar puncture experience in children with spinal muscular atrophy during a phase 1 open-label study of nusinersen and its extension. During the studies, 73 lumbar punctures were performed in 28 patients 2 to 14 years of age with type 2/3 spinal muscular atrophy. No complications occurred in 50 (68%) lumbar punctures; in 23 (32%) procedures, adverse events were attributed to lumbar puncture. Most common adverse events were headache (n = 9), back pain (n = 9), and post–lumbar puncture syndrome (n = 8). In a subgroup analysis, adverse events were more frequent in older children, children with type 3 spinal muscular atrophy, and with a 21- or 22-gauge needle compared to a 24-gauge needle or smaller. Lumbar punctures were successfully performed in children with spinal muscular atrophy; lumbar puncture–related adverse event frequency was similar to that previously reported in children.

Keywords: lumbar puncture, spinal muscular atrophy, antisense oligonucleotide, drug delivery

Advances in the identification of the genetic basis of neurologic diseases have enabled the emerging development of therapies to treat these diseases based on the known genetic mechanisms and deficiencies. However, drug delivery to the central nervous system remains a key challenge. Intrathecal injection via lumbar puncture provides a direct route of delivery that has traditionally been focused on malignancy-directed chemotherapeutics and pain management,1 but is increasingly being used in clinical trials assessing neurologic therapies.2,3

Nusinersen (ISIS-SMNRx or ISIS 396443) is an antisense oligonucleotide currently in development for spinal muscular atrophy, an autosomal recessive motor neuron disease associated with progressive muscular atrophy and weakness involving limbs and, more variably, bulbar and respiratory muscles.4,5 Spinal muscular atrophy affects approximately 1:10 000 births,6 and is classified into clinical subtypes (types 0-4) differentiated by age of onset and highest motor function.7 Nusinersen is designed to alter splicing of SMN2 messenger RNA and increase the amount of functional SMN protein produced, thus compensating for the genetic defect in the SMN1 gene.8,9 Nusinersen, currently under evaluation in phase 3 clinical trials in infants and children with spinal muscular atrophy, is administered via lumbar puncture and intrathecal injection directly into the cerebrospinal fluid, from where it distributes to the spinal cord and the brain.

Although lumbar puncture is routinely performed for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in children and infants,10 it is infrequently performed in patients with spinal muscular atrophy. Lumbar puncture is generally a safe and straightforward procedure, but side effects, such as headache, back pain, and transient or persistent cerebrospinal fluid leakage (post–lumbar puncture syndrome), have been documented.11–13 In addition, in children with spinal muscular atrophy who often experience complications such as scoliosis, lumbar punctures might be technically more challenging to perform. The objective of this analysis was to summarize our clinical trial experience with lumbar punctures for intrathecal nusinersen drug delivery in a phase 1 study in children with spinal muscular atrophy14 and to develop recommendations for procedures in a pediatric population with a severe neuromuscular disease.

Methods

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Participant Consents

These trials were conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the European Union Clinical Trials Directive, and local regulatory requirements. Approval for the study protocols and all amendments were obtained from Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (Approval #AAAI6758 and #AAAK5458). Written informed consent and assent (if applicable) were obtained before any evaluations were conducted for eligibility. The trials are registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01494701 and NCT01780246).

Phase 1 and Extension Study Designs

The phase 1 study was a first-in-human, open-label, escalating-dose study to assess the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of a single intrathecal dose (1, 3, 6, or 9 mg) of nusinersen in children with spinal muscular atrophy. Each dose cohort had 6 to 10 participants (N = 28). Upon completion, all participants had the opportunity to enroll in a subsequent extension study and receive additional dosing with nusinersen. The methods and results of the phase 1 study and its extension are detailed elsewhere.14 Briefly, medically stable spinal muscular atrophy participants 2 to 14 years of age were enrolled in 4 sites in the United States (Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA; Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY; UT Southwestern Medical Center–Children’s Medical Center Dallas, Dallas, TX; and University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, UT). Eligible participants had to be able to complete all study procedures, meet age-appropriate institutional guidelines for lumbar puncture procedures, and have a life expectancy of >2 years. Participants were excluded for serious respiratory insufficiency, hospitalization for surgery or pulmonary event within the past 2 months, active infection at screening, history of brain or spinal cord disease or bacterial meningitis, presence of implanted cerebrospinal fluid drainage shunt, clinically significant laboratory abnormalities, any ongoing medical condition that would interfere with the conduct and assessments of the study, or treatment with another investigational drug within 1 month of screening. Patients with scoliosis were allowed to participate if, in the opinion of the investigator, a lumbar puncture could be performed safely.

Lumbar Puncture Procedures

A total of 3 lumbar punctures were scheduled during the 2 trials for drug delivery and/or follow-up collection of cerebrospinal fluid for safety and pharmacokinetic analyses. Drug was administered via intrathecal injection of a 5-mL bolus over 1 to 3 minutes. The protocol recommended a 22- to 25-gauge spinal anesthesia needle (21-gauge needle allowed if participant’s weight or condition dictated) and that the lumbar punctures were performed at the L3-L4 disc space or 1 level above or 1 to 2 levels below, as needed. In all cases, 5 to 6 mL of cerebrospinal fluid was collected before drug injection. Participants were encouraged to lie flat for an hour after the procedure. Anesthesia and/or sedation and fluoroscopy or ultrasonography were permitted to facilitate the procedure and varied by institution at the discretion of the investigators at each site.

Participants underwent the first lumbar puncture on day 1 for cerebrospinal fluid collection and nusinersen dosing, the second lumbar puncture on day 8 or day 29 for cerebrospinal fluid collection, and the third lumbar puncture during the extension study for cerebrospinal fluid collection and redosing with nusinersen 9 to 14 months after the initial lumbar puncture.

Safety and Tolerability

In the phase 1 single-dose study, participants were initially monitored for safety and tolerability for 29 days (1-mg and 3-mg cohorts) or 85 days (6-mg and 9-mg cohorts) post dosing. Participants enrolled in the extension study were monitored over 169 days post dosing. Safety reporting included adverse events related to lumbar puncture, and a subgroup analysis was performed to compare reported lumbar puncture–related adverse events by needle size, participant age, and spinal muscular atrophy type.

Results

A total of 28 children were enrolled and received dosing in the phase 1 study; 15 children had spinal muscular atrophy type 2 and 13 had spinal muscular atrophy type 3 (Table 1). At baseline, participant mean (range) age was 6.1 (2.0-14.0) years, 17 were female, 10 were ambulatory, and 13 had scoliosis. One child had vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rods inserted and the pedicle screws were inserted into T2, T3, and T4 with fixation of the growing rods to the pelvis, leaving the lumbar spine area spared. The first and second lumbar punctures were performed on 28 and 27 children in the parent study, respectively, and the third on 18 children who re-enrolled in the extension study. Of the 10 children not re-enrolling, 6 re-enrolled in a multiple-dose study of nusinersen and 4 decided not to enroll. Of these, 1 child did not re-enroll for reasons related to the lumbar puncture procedure. This was a 12-year-old girl with spinal muscular atrophy type 2 who had severe scoliosis at baseline and in whom the second fluoroscopically guided lumbar puncture procedure was not performed successfully at day 8 in the phase 1 study.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics of Participants (N = 28).

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 17 (61) |

| Mean (range) age, y | 6.1 (2.0-14.0) |

| Mean (SD) weight, kg | 23.6 (14.7) |

| SMA, n (%) | |

| type 2 | 15 (54) |

| type 3 | 13 (46) |

| Ambulatory, yes, n (%) | 10 (36) |

| Scoliosis, yes, n (%) | 13 (46) |

| Spinal rods, n (%) | 1 (4) |

Abbreviation: SMA, spinal muscular atrophy.

Participants were enrolled and treated in 4 sites; the institutional lumbar puncture procedures used in each site are reported in Table 2. Both cutting-tip and atraumatic (pencil-point) spinal needles were used and the general practice was to perform the procedure in the lateral decubitus or prone position by pediatric anesthesiologists, neurologists, or neuroradiologists in either inpatient or outpatient settings. All sites performed the procedure under intravenous (midazolam, ketamine, fentanyl, remifentanil, and/or propofol) or inhaled anesthesia/sedation (sevoflurane and/or nitrous oxide). Some sites also reported the use of topical anesthesia (EMLA cream) or locally injected lidocaine (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of Lumbar Puncture Procedural Differences Between the Study Sites.a

| Lumbar Puncture Procedural Details | Columbia University (n = 28) | University of Utah (n = 25) | Boston Children’s Hospital (n = 10) | University of Texas (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Needle size(s) used |

|

|

|

|

| Needle type(s) |

|

|

|

|

| Placement |

|

|

|

|

| Fluoroscopy, yes/no |

|

|

|

|

| Ultrasound, yes/no |

|

|

|

|

| Anesthesia and/or sedation, yes/no |

|

|

|

|

| If yes, type(s) |

|

|

|

|

| Specialty of performing clinician |

|

|

|

|

| Participant position |

|

|

|

|

| Place of procedure |

|

|

|

|

| Monitoring |

|

|

|

|

Abbreviations: ECG, electrocardiogram; IV, intravenous.

an’s indicate the number of lumbar punctures performed at each site (total 73).

bFluoroscopy was used routinely per institutional practice.

cOnly in some participants.

dIn participants with severe scoliosis only.

eFor children receiving lumbar puncture.

fFor children receiving IV sedation.

A total of 74 lumbar punctures were attempted and 73 procedures were performed. The majority of lumbar punctures were carried out using either a 22- (48%) or 25-gauge (37%) needle inserted in the L3-L4 (44%) or L4-L5 (29%) space. Nearly half (44%) of the lumbar punctures were guided using fluoroscopy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of Procedural Details per Lumbar Puncture.a

| Lumbar Puncture Procedural Details | First Lumbar Puncture (n = 28) | Second Lumbar Puncture (n = 27) | Third Lumbar Puncture (n = 18) | Total No. of Lumbar Punctures (N = 73) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gauge of needle | ||||

| 21 | 2 (7) | 1 (4) | 0 | 3 (4) |

| 22 | 13 (46) | 14 (52) | 8 (44) | 35 (48) |

| 24 | 4 (14) | 2 (7) | 1 (6) | 7 (10) |

| 25 | 9 (32) | 9 (33) | 9 (50) | 27 (37) |

| 27 | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Needle insertion site | ||||

| L2-L3 | 4 (14) | 8 (30) | 5 (28) | 17 (23) |

| L3-L4 | 11 (39) | 13 (48) | 8 (44) | 32 (44) |

| L4-L5 | 12 (43) | 5 (19) | 4 (22) | 21 (29) |

| L5-S1 | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 1 (6) | 3 (4) |

| Use of fluoroscopy, yes | 14 (50) | 12 (44) | 6 (33) | 32 (44) |

| Treatment for post–lumbar puncture syndrome, yesb | 5 (18) | 1 (4) | 1 (6) | 7 (10) |

aValues are n (%).

bParticipants were treated for post–lumbar puncture headache with acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and/or caffeine citrate.

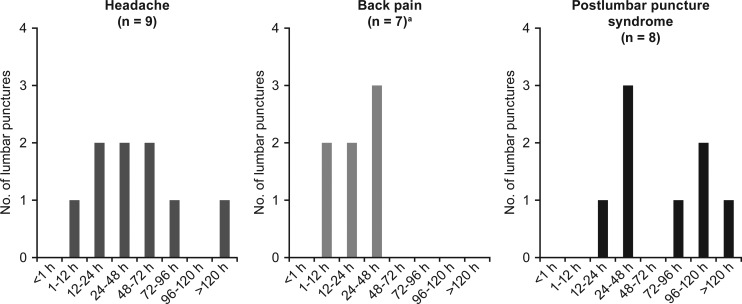

Of the 73 lumbar punctures performed, the majority (n = 50; 68%) had no complications; lumbar puncture–related adverse events were reported in 23 (32%; Table 4). The most common adverse events were headache (9 events), back pain (9 events), and post–lumbar puncture syndrome (8 events; post–dural puncture headache with or without vomiting), and all events resolved without long-term complications. The timing of the adverse events varied; 67% (n = 6) of the headaches occurred 12 to 72 hours post lumbar puncture, whereas back pain was reported 0 to 48 hours post procedure (Figure 1). Fifty percent (n = 4) of the post–lumbar puncture syndrome events occurred between 12 and 48 hours, with the remaining occurring after 72 hours (Figure 1). All 8 incidences of post–lumbar puncture syndrome were managed with acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and/or caffeine citrate for headache. All 8 cases of post–lumbar puncture syndrome resolved with conservative therapy, and none of the 7 participants needed an epidural blood patch. In 1 case, a blood patch was performed prophylactically during the second lumbar puncture procedure in a patient who had experienced a post–dural puncture headache following the first procedure. No post–dural puncture headache resulted after the second procedure. Resolution of the post–lumbar puncture syndrome occurred between 4 hours and 5 days, with the majority of the events (50% of cases) lasting 1 to 2 days.

Table 4.

Summary of Reported Lumbar Puncture–Related Adverse Events.

| Adverse Event | First Lumbar Puncture (n = 28) | Second Lumbar Puncture (n = 27) | Third Lumbar Puncture (n = 18) | All Lumbar Punctures (N = 73) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | Events, n | Patients, n (%) | Events, n | Patients, n (%) | Events, n | Total, n (%)a | Total Events, n | |

| Patients reporting ≥1 adverse event | 9 (32) | 20 | 8 (30) | 10 | 6 (33) | 8 | 23 (32) | 38 |

| Headache | 4 (14) | 4 | 4 (15) | 4 | 1 (6) | 1 | 9 (12) | 9 |

| Back pain | 2 (7)b | 3 | 3 (11) | 3 | 3 (17) | 3 | 8 (11) | 9 |

| Post–lumbar puncture syndrome | 5 (18)b | 6 | 1 (4) | 1 | 1 (6) | 1 | 7 (10) | 8 |

| Nausea | 2 (7) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (3) | 2 |

| Puncture site pain | 1 (4) | 1 | 1 (4) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 (3) | 2 |

| Paresthesia | 1 (4) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 |

| Pain in extremity | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 |

| Procedural nausea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6) | 1 | 1 (1) | 1 |

| Procedural pain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6) | 1 | 1 (1) | 1 |

| Vomiting | 1 (4) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 |

| Puncture site reaction | 1 (4) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 |

| Dehydration | 1 (4) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 |

| Hypotension | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6) | 1 | 1 (1) | 1 |

aTotal number of adverse events in all 73 lumbar punctures performed.

bParticipants reporting >1 adverse event after each lumbar puncture were counted only once for the lumbar puncture.

Figure 1.

Time of onset of headache, back pain, and post–lumbar puncture syndrome. Most common lumbar puncture–associated adverse events (N = 73) and their time of onset are shown. aTime of onset for 2 cases of back pain were not reported.

A subgroup analysis compared lumbar puncture complications with needle size, participant age, and spinal muscular atrophy type and demonstrated that headache, back pain, and post–lumbar puncture syndrome were observed more frequently when a 21- or 22-gauge needle was used, in older children (8-14 years of age), and in children with spinal muscular atrophy type 3 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary of Reported Lumbar Puncture–Related Adverse Events by Subgroup.a

| Adverse Event | Gauge of Needle: 21/22 (n = 38) | Gauge of Needle: 24/25/27 (n = 35) | Patient Age: 2-7 y (n = 47) | Patient Age: 8-14 y (n = 26) | Patients With SMA type 2 (n = 39) | Patients With SMA type 3 (n = 34) | Total No. of Procedures (N = 73) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Headache | 8 (21) | 1 (3) | 3 (6) | 6 (23) | 4 (10) | 5 (15) | 9 (12) |

| Back pain | 5 (13) | 3 (9) | 4 (9) | 4 (15) | 2 (5) | 6 (18) | 8 (11) |

| Post–lumbar puncture syndrome | 5 (13) | 2 (6) | 2 (4) | 5 (19) | 2 (5) | 5 (15) | 7 (10) |

| Nausea | 2 (5) | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Puncture site pain | 2 (5) | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 2 (5) | 0 | 2 (3) |

| Paresthesia | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 1 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Pain in extremity | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Procedural nausea | 0 | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Procedural pain | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 1 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Vomiting | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Puncture site reaction | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Dehydration | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Hypotension | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (1) |

Abbreviation: SMA, spinal muscular atrophy.

aValues are n (%).

Discussion

Lumbar puncture–related adverse events are well documented in children and infants,11–13 with the most common complications being back pain and headache with an incidence of 11% to 40% and 12% to 33%, respectively.11,12,15 Although the incidence of post–lumbar puncture syndrome in children is not well reported, 4% to 11% of the reported headaches are classified as post–dural puncture headaches.11,12,15 In addition to headache, post–lumbar puncture syndrome can also include transient effects of backache, dizziness, nausea with or without vomiting, numbness, and lower extremity weakness.16,17 In rare cases, more severe symptoms have been reported, such as intracranial hypotension, epidural hematoma, and cauda equina syndrome.18,19 In this phase 1 study and its extension, 73 lumbar punctures were performed for cerebrospinal fluid collection and/or intrathecal drug administration in children with spinal muscular atrophy. Approximately one-third of the procedures were associated with adverse events, most commonly with headache, back pain, and post–lumbar puncture syndrome, and the majority occurred within 72 hours after the procedure. A subgroup analysis demonstrated that the highest incidence of adverse events was reported in older children, children with spinal muscular atrophy type 3, and when a larger 21- or 22-gauge needle was used.

Using a 24-gauge needle or smaller atraumatic needle inserted with the bevel parallel to the dura fibers had been suggested to considerably reduce damage to the dura and consequently decrease the risk for cerebrospinal fluid leak after lumbar puncture,20,21 including in children.11,22 Needle type (atraumatic or traumatic) may have a greater impact on the reported incidence of post–dural puncture headache than needle size. Turnbull et al21 found the incidence of post–dural puncture headache varied from 0.6% to 4% (22 gauge) and 0% to 14.5% (25 gauge) with an atraumatic (Whitacre) needle versus 36% (22 gauge) and 3% to 25% (25-gauge) with a traumatic cutting-tip (Quincke) needle, respectively. Although using an atraumatic needle may reduce the incidence of post–lumbar puncture syndrome, some studies have identified increased failure rate23,24 and paresthesia23 when using an atraumatic needle versus a cutting-tip spinal needle. However, differences in success rate were not found in other studies.15,22,25

Nearly half of the lumbar punctures were successfully carried out in children with spinal muscular atrophy using a 24-gauge spinal needle or smaller and, consequently, were associated with reduced incidence of headache and post–lumbar puncture syndrome compared with procedures performed using a 21- or 22-gauge needle. After initial experiences, all investigational sites switched to using a smaller needle size, except when use of a larger needle size was required (eg, scoliosis). The higher incidence of adverse events, particularly headaches, observed among older children and/or in children with spinal muscular atrophy type 3 were likely related to the use of larger bore/gauge spinal needles, cutting-tip needles (eg, Quincke type), multiple attempts, and/or due to technical difficulties resulting from increased body weight and the presence of scoliosis or excessive lumbar lordosis.

In most cases, post–dural puncture headache can be successfully treated with conservative therapy, consisting of bed rest in prone or lateral position, hydration, oral or intravenous caffeine, anti-nausea or antiemetic therapy, and/or analgesics.20,21,26,27 However, in children with post–dural puncture headaches persisting >48 hours or that worsen despite the use of conservative therapy, a therapeutic epidural blood patch may be indicated.27,28 Although there is conflicting evidence, some studies also support the use of a prophylactic blood patch to prevent post–dural puncture headache; however, none of these studies included children.29 In this study, all post–dural puncture headaches resolved with conservative treatment of bed rest, adequate hydration, and administration of caffeine and other analgesics, and therapeutic epidural blood patches proved unnecessary.

Other considerations that may facilitate lumbar puncture success in children include patient positioning and the use of spinal ultrasound. Few studies in children and infants have compared the feasibility of lumbar puncture in upright versus lateral recumbent position. Both the seated and lateral decubitus position with hip flexion increased the interspinous space compared with hip neutral positions and may increase lumbar puncture success rate.30–33 The use of spinal ultrasound may facilitate the lumbar puncture procedure,34,35 and is favored over fluoroscopy in children, particularly if repeated procedures are planned, to minimize radiation exposure and cost.36 In this study, lumbar punctures were performed in the lateral decubitus or prone position, and nearly half of the lumbar punctures were successfully done without ultrasound and/or fluoroscopy. However, in patients with spinal muscular atrophy with scoliosis, spinal rods, or other hardware, the use of imaging may be warranted to facilitate the procedure and increase the success of intrathecal medication delivery. Lumbar punctures were successfully performed in the participants with scoliosis (13 in the first procedure, 12 in the second procedure, and 11 in the third procedure) and in the one child who had spinal rods. The second fluoroscopy-guided procedure was unsuccessful in only 1 patient because of scoliosis. This suggests that in some cases scoliosis might hinder lumbar puncture success in children with spinal muscular atrophy, but the frequency needs to be confirmed in larger studies.

General anesthesia and/or sedation are routinely performed in children to reduce procedure-related anxiety, pain, and distress, and to increase the overall success rate of lumbar puncture.37–39 However, increasing concerns about the impact of repeated anesthesia exposure on the developing nervous system in infants and young children must be carefully considered when repeated procedures are planned.40 All 73 lumbar punctures performed in this study were performed using either intravenous (midazolam, ketamine, fentanyl, remifentanil, and/or propofol) or inhaled anesthesia/sedation (sevoflurane, nitrous oxide), with no associated complications reported. Children with spinal muscular atrophy who have moderate to severe muscle weakness and/or severe scoliosis are at higher risk for hypoventilation and respiratory compromise. Thus, if deep sedation or general anesthesia is used, assisted ventilation may be required by either non-invasive or invasive means. The use of local topical or subcutaneous anesthesia may help decrease the requirements for sedation. Based on our experience in this study, we recommend the most minimal use of sedative medications or anesthesia to permit safe and effective completion of the procedure.

The limitations of this study include a small sample size and the limited number of lumbar puncture procedures performed. Further experiences with lumbar puncture in children and infants with spinal muscular atrophy are needed to add to this knowledge.

Conclusions

In summary, repeated lumbar punctures were successfully performed in children with spinal muscular atrophy in the initial nusinersen clinical studies. The frequency of lumbar puncture–related adverse events in children with spinal muscular atrophy was similar to that previously reported in children and infants, and were mainly limited to headache, back pain, and post–lumbar puncture syndrome. A 24-gauge needle or smaller was successfully used in children with spinal muscular atrophy to perform lumbar puncture with lower incidence of complications, suggesting that using a 24-gauge or smaller needle would likely reduce the chance of adverse events. Bed rest, adequate hydration, oral caffeine, and/or analgesics were sufficient to resolve post–lumbar puncture headache/syndrome without the need of a therapeutic blood patch in all patients. Provisions for ultrasound guidance may be warranted in future research protocols given the potential benefit of reduced radiation exposure compared to fluoroscopy, especially in cases of serial procedures for repeated drug delivery. Overall, we conclude that intrathecal delivery of medication is feasible, safe, and well tolerated. Our experience may prove useful for guiding the development of best practice strategies for safe and effective intrathecal delivery of nusinersen and/or other promising emerging therapies for spinal muscular atrophy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants and their parents/families, the study staff, study coordinators, and additional investigators (Drs Claudia Chiraboga, Basil Darras, and Susan Iannoconne) at the clinical trial sites who made the studies possible, and the SMA Foundation. Biogen provided funding for medical writing support in the development of this paper; Maria Hovenden from Excel Scientific Solutions wrote the first draft of the manuscript based on input from authors, and Kristen DeYoung from Excel Scientific Solutions copyedited and styled the manuscript per journal requirements. Biogen reviewed and provided feedback on the paper. The authors had full editorial control of the paper, and provided their final approval of all content.

Author Note: Clinical trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT01494701 (An Open-label Safety, Tolerability, and Dose-Range Finding Study of ISIS SMNRx in Patients With Spinal Muscular Atrophy; URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01494701) and NCT01780246 (An Open-label Safety and Tolerability Study of ISIS SMNRx in Patients With Spinal Muscular Atrophy Who Previously Participated in ISIS 396443-CS1; URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01780246)

Author Contributions: MH, KJS, NS, AK, and AF-G coordinated and supervised data collection and performed study procedures (eg, lumbar punctures or anesthesia) at the 4 clinical sites, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. SX carried out the initial data analyses, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. KB conceptualized and designed the study, participated in the data analysis, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: KJS has received funding for clinical trial contracts from Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. She was working at the Department of Neurology, University of Utah, at the time of the study. SX is a full-time employee of Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. KB was a full-time employee of Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. at the time of the study and manuscript preparation.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Funding for medical writing support was provided by Biogen. AF-G’s institution has received funding from Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. through other departments. The phase 1 (NCT01494701) and extension (NCT01780246) clinical studies were funded by Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Ethical Approval: Approval for the study protocols and all amendments were obtained from Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Approval nos. AAAI6758 and AAAK5458). Written informed consent and assent (if applicable) were obtained before any evaluations were conducted for eligibility.

References

- 1. Papisov MI, Belov VV, Gannon KS. Physiology of the intrathecal bolus: the leptomeningeal route for macromolecule and particle delivery to CNS. Mol Pharm. 2013;10:1522–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miller TM, Pestronk A, David W, et al. An antisense oligonucleotide against SOD1 delivered intrathecally for patients with SOD1 familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a phase 1, randomised, first-in-man study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:435–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Multiple sclerosis. Management of multiple sclerosis in primary and secondary care. NICE Guidance. Published November 2003. [PubMed]

- 4. Crawford TO, Pardo CA. The neurobiology of childhood spinal muscular atrophy. Neurobiol Dis. 1996;3:97–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lefebvre S, Burglen L, Reboullet S, et al. Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell. 1995;80:155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lunn MR, Wang CH. Spinal muscular atrophy. Lancet. 2008;371:2120–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Russman BS. Spinal muscular atrophy: clinical classification and disease heterogeneity. J Child Neurol. 2007;22:946–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hua Y, Sahashi K, Hung G, et al. Antisense correction of SMN2 splicing in the CNS rescues necrosis in a type III SMA mouse model. Genes Devel. 2010;24:1634–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hua Y, Vickers TA, Okunola HL, Bennett CF, Krainer AR. Antisense masking of an hnRNP A1/A2 intronic splicing silencer corrects Ital splicing in transgenic mice. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:834–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bonadio W. Pediatric lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid analysis. J Emerg Med. 2014;46:141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lowery S, Oliver A. Incidence of postdural puncture headache and backache following diagnostic/therapeutic lumbar puncture using a 22G cutting spinal needle, and after introduction of a 25G pencil point spinal needle. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008;18:230–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ebinger F, Kosel C, Pietz J, Rating D. Headache and backache after lumbar puncture in children and adolescents: a prospective study. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1588–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kiechl-Kohlendorfer U, Unsinn KM, Schlenck B, Trawöger R, Gassner I. Cerebrospinal fluid leakage after lumbar puncture in neonates: incidence and sonographic appearance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:231–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chiriboga C SK, Darras BT, Iannaccone ST, et al. Results from a phase 1 study of nusinersen (ISIS-SMNRX) in children with spinal muscular atrophy. Neurology. 2016;86(10):890–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kokki H, Heikkinen M, Turunen M, Vanamo K, Hendolin H. Needle design does not affect the success rate of spinal anaesthesia or the incidence of postpuncture complications in children. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2000;44:210–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koch BL, Moosbrugger EA, Egelhoff JC. Symptomatic spinal epidural collections after lumbar puncture in children. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1811–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ng WH, Drake JM. Symptomatic spinal epidural CSF collection after lumbar puncture in a young adult: case report and review of literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26:259–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gordon N. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51:932–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Amini A, Liu JK, Kan P, Brockmeyer DL. Cerebrospinal fluid dissecting into spinal epidural space after lumbar puncture causing cauda equina syndrome: review of literature and illustrative case. Childs Nerv Syst. 2006;22:1639–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ahmed SV, Jayawarna C, Jude E. Post lumbar puncture headache: diagnosis and management. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:713–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Turnbull DK, Shepherd DB. Post-dural puncture headache: pathogenesis, prevention and treatment. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91:718–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Apiliogullari S, Duman A, Gok F, Akillioglu I. Spinal needle design and size affect the incidence of postdural puncture headache in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;20:177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sharma SK, Gambling DR, Joshi GP, Sidawi JE, Herrera ER. Comparison of 26-gauge Atraucan and 25-gauge Whitacre needles: insertion characteristics and complications. Can J Anaesth. 1995;42:706–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thomas SR, Jamieson DR, Muir KW. Randomised controlled trial of atraumatic versus standard needles for diagnostic lumbar puncture. BMJ. 2000;321:986–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kokki H, Hendolin H, Turunen M. Postdural puncture headache and transient neurologic symptoms in children after spinal anaesthesia using cutting and pencil point paediatric spinal needles. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1998;42:1076–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Basurto Ona X, Martínez García L, Solà I, Bonfill Cosp X. Drug therapy for treating post-dural puncture headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;8:CD007887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Janssens E, Aerssens P, Alliët P, Gillis P, Raes M. Post-dural puncture headaches in children. A literature review. Eur J Pediatr. 2003;162:117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kokki M, Sjövall S, Kokki H. Epidural blood patches are effective for postdural puncture headache in pediatrics—a 10-year experience. Paediatr Anaesth. 2012;22:1205–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boonmak P, Boonmak S. Epidural blood patching for preventing and treating post-dural puncture headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD001791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Öncel S, Günlemez A, Anik Y, Alvur M. Positioning of infants in the neonatal intensive care unit for lumbar puncture as determined by bedside ultrasonography. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2013;98:F133–F135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abo A, Chen L, Johnston P, Santucci K. Positioning for lumbar puncture in children evaluated by bedside ultrasound. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1149–e1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Apiliogullari S, Duman A, Gok F, Ogun CO, Akillioglu I. The effects of 45 degree head up tilt on the lumbar puncture success rate in children undergoing spinal anesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008;18:1178–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Molina A, Fons J. Factors associated with lumbar puncture success. Pediatrics. 2006;118:842–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kil HK, Cho JE, Kim WO, Koo BN, Han SW, Kim JY. Prepuncture ultrasound-measured distance: an accurate reflection of epidural depth in infants and small children. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32:102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim S, Adler DK. Ultrasound-assisted lumbar puncture in pediatric emergency medicine. J Emerg Med. 2014;47:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yu SD, Chen MY, Johnson AJ. Factors associated with traumatic fluoroscopy-guided lumbar punctures: a retrospective review. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:512–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ljungman G, Gordh T, Sörensen S, Kreuger A. Lumbar puncture in pediatric oncology: conscious sedation vs. general anesthesia. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;36:372–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pinheiro JM, Furdon S, Ochoa LF. Role of local anesthesia during lumbar puncture in neonates. Pediatrics. 1993;91:379–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Anghelescu DL, Burgoyne LL, Faughnan LG, Hankins GM, Smeltzer MP, Pui CH. Prospective randomized crossover evaluation of three anesthetic regimens for painful procedures in children with cancer. J Pediatr. 2013;162:137–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Psaty BM, Platt R, Altman RB. Neurotoxicity of generic anesthesia agents in infants and children: an orphan research question in search of a sponsor. JAMA. 2015;313:1515–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]