Abstract

Background:

The Banff Patella Instability Instrument (BPII) is a disease-specific, patient-reported, quality-of-life outcome measure designed to assess patients with patellofemoral instability. The iterative assessment of the validity, reliability, and responsiveness of a health-related patient-reported outcome measure is vital to the development of a high-quality evaluation tool.

Purpose:

To assess the concurrent validity of the BPII to the Norwich Patellar Instability (NPI) score and the Kujala score.

Study Design:

Cohort study; Level of evidence, 2.

Methods:

A total of 74 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of recurrent patellofemoral instability completed the BPII, NPI, and Kujala scores at the initial orthopaedic consultation. A Pearson r correlation coefficient was computed to determine the relationship between each of these patient-reported outcomes.

Results:

There were statistically significant correlations between the BPII and the NPI score (r = −0.53; P < .001) as well as the BPII and the Kujala score (r = 0.50; P < .001).

Conclusion:

This study demonstrated a moderately strong correlation of the BPII to other outcome measures used to evaluate patients with patellofemoral instability. This study adds further validity to the BPII in accordance with the COSMIN (COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments) guidelines.

Keywords: patellofemoral instability, Banff Patella Instability Instrument (BPII), Norwich Patellar Instability score (NPI), Kujala score, outcome measure, quality of life, COSMIN

Patellofemoral instability is a common knee problem that results in significant morbidity. It is frequently associated with instability, pain, decreased activity, long-term osteoarthritis, and reduced quality of life.2,4,8,13,17 Understanding the results of interventions for patellofemoral instability will influence the treatment of this disorder, and performing quality research in this growing field requires the use of valid and reliable outcome measures. Outcome measures can be subjective or objective, patient reported or clinician reported. Each of these outcome measures is important; however, only patient-reported outcomes provide patients with the opportunity to self-report their treatment results for a designated construct. Determining whether treatments help patients has been noted as “the ultimate measure by which to judge the quality of a medical effort.”1

The COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) initiative was undertaken to provide clinicians and researchers with tools to identify appropriate high-quality health measurement instruments.12 The COSMIN group utilized an international Delphi study to develop a critical appraisal tool (the COSMIN checklist), which can be used to evaluate the methodological quality of studies assessing health measurement instruments.11

Key to the COSMIN initiative was an international consensus on terminology, definitions, and a taxonomy of the relationships of measurement properties of health-related patient-reported outcomes.12 The taxonomy identified 3 quality domains: validity, reliability, and responsiveness. Each domain contains at least 1 measurement property (Figure 1). For example, the validity domain identifies 3 measurement properties: content, construct, and criterion validity. Some measurement properties are further defined into components or aspects, for example, construct validity contains structural validity, hypotheses testing, and cross-cultural validity. The COSMIN checklist can be used to guide the design of a health measurement instrument as well as to report on the measurement properties of these tools.10,20

Figure 1.

COSMIN taxonomy of relationships of measurement properties. Reprinted with permission from Mokkink et al.12 HR-PRO, health-related patient-reported outcomes instrument.

The Kujala score5 is a 13-item questionnaire that was developed to evaluate the subjective symptoms and functional limitations in patients with patellofemoral disorders. This questionnaire was initially tested on 4 different patient cohorts, including anterior knee pain, patellar subluxation, patellar dislocation, and controls. Kujala et al5 identified differences in mean scores between the patient cohorts and indicated certain questions were more important for differentiating between groups. Since its publication in 1993, this score has been widely used in the assessment of patients with anterior knee pain and patellofemoral instability. The Kujala score has undergone limited additional development beyond the original research in 1993.

In March 2013, the Norwich Patellar Instability (NPI) score was first published and its development, validation, and internal consistency reported.16 The NPI is a self-administered 19-item questionnaire used to assess physical symptoms in patients with patellofemoral instability. The questionnaire was completed by 102 patients and compared with physical examination findings as well as the Knee Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), Kujala, and Lysholm knee scores. The NPI study reported on the initial validation and internal consistency of this new disease-specific measure of patient-perceived patellar instability.

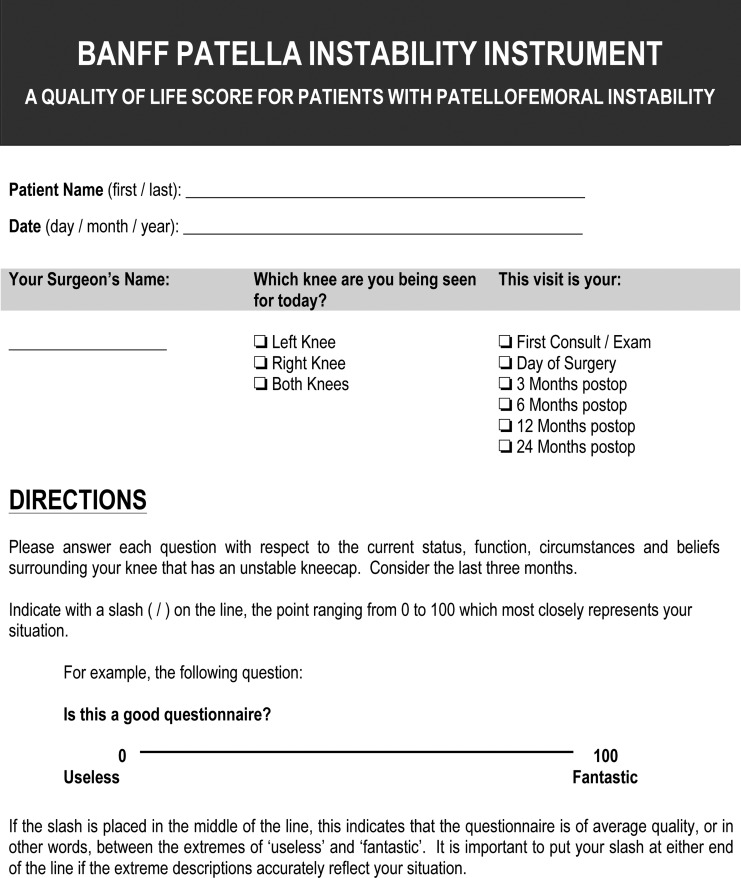

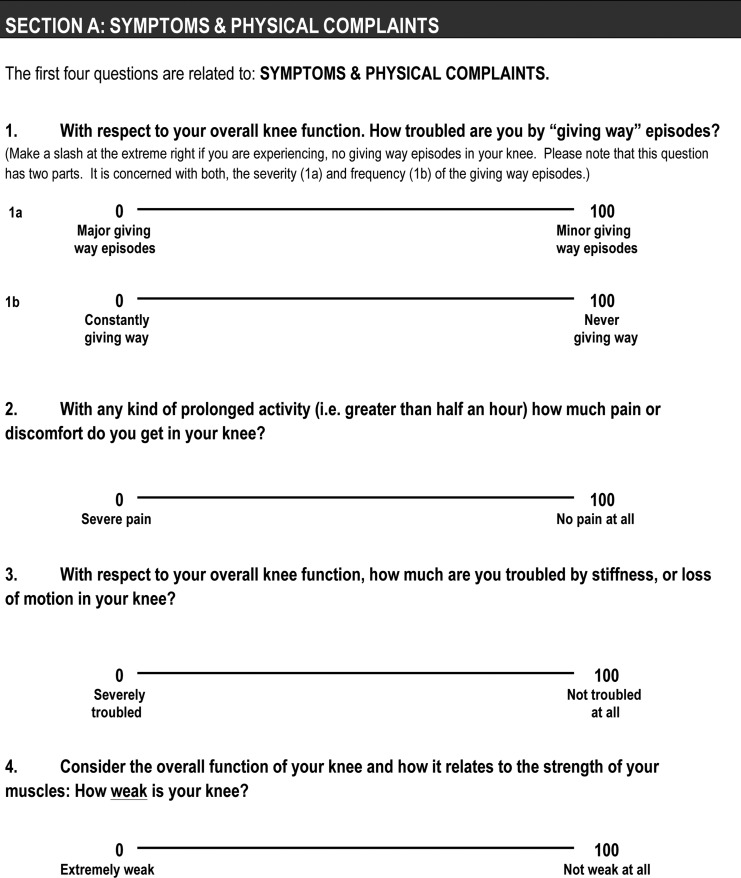

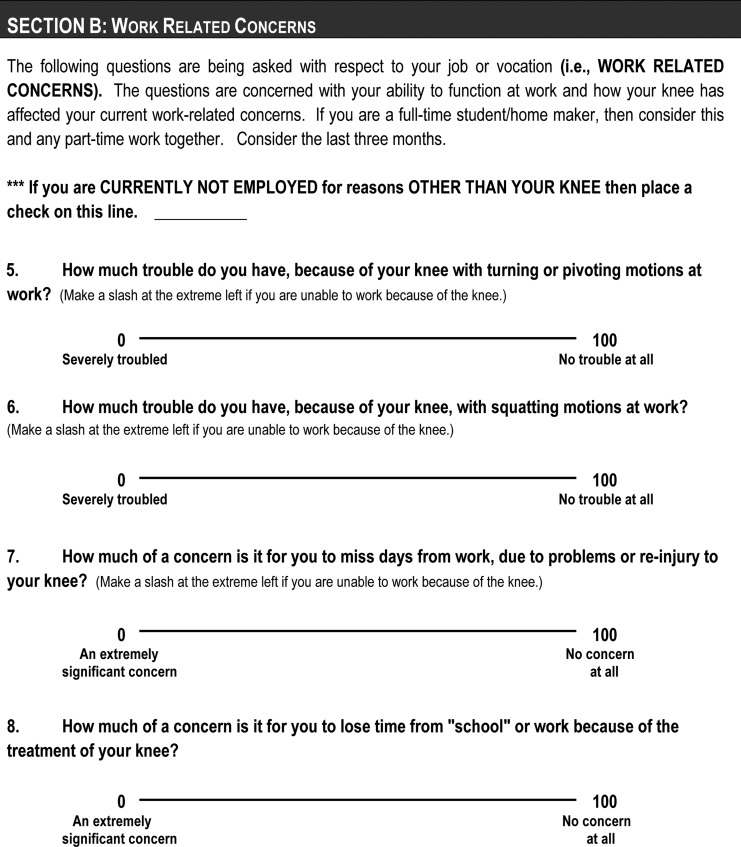

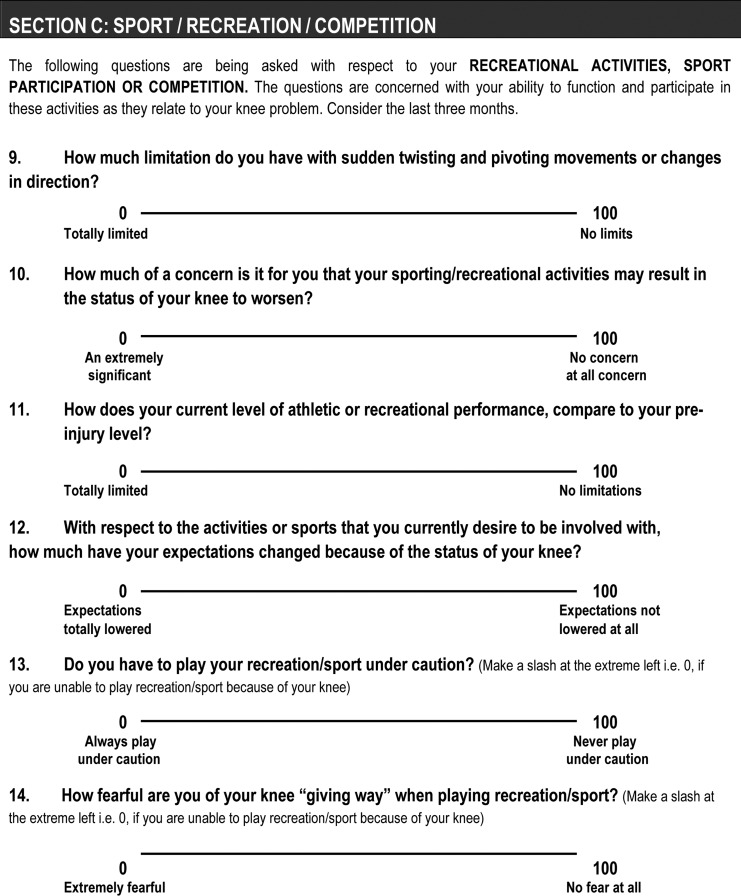

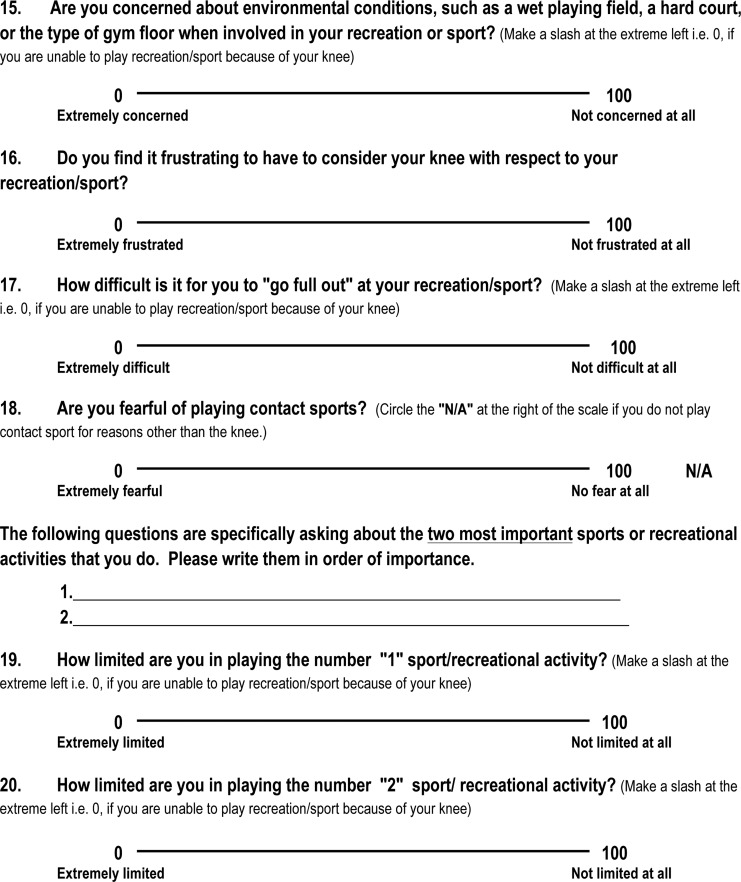

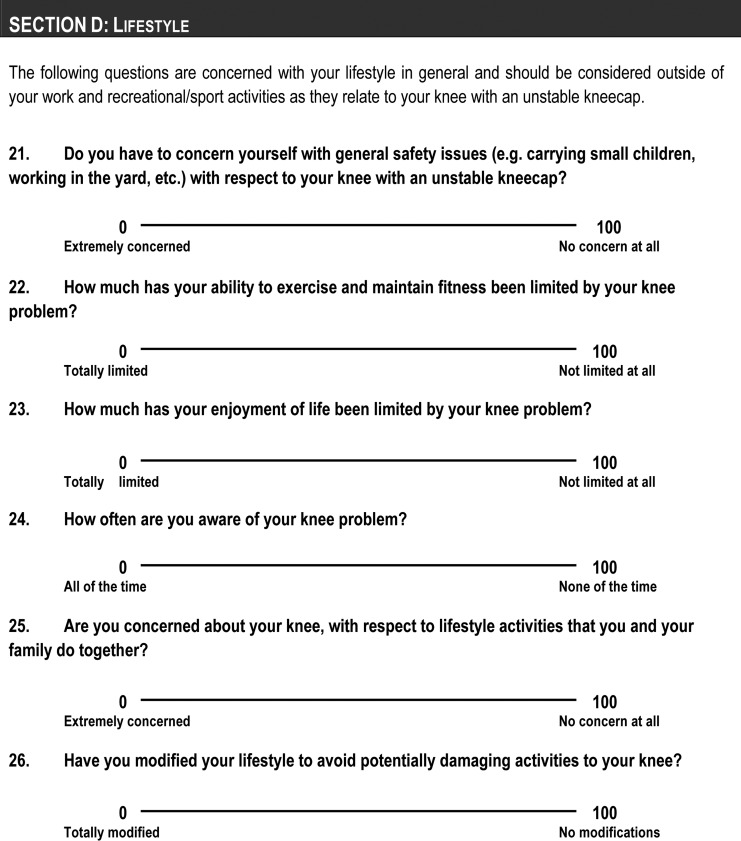

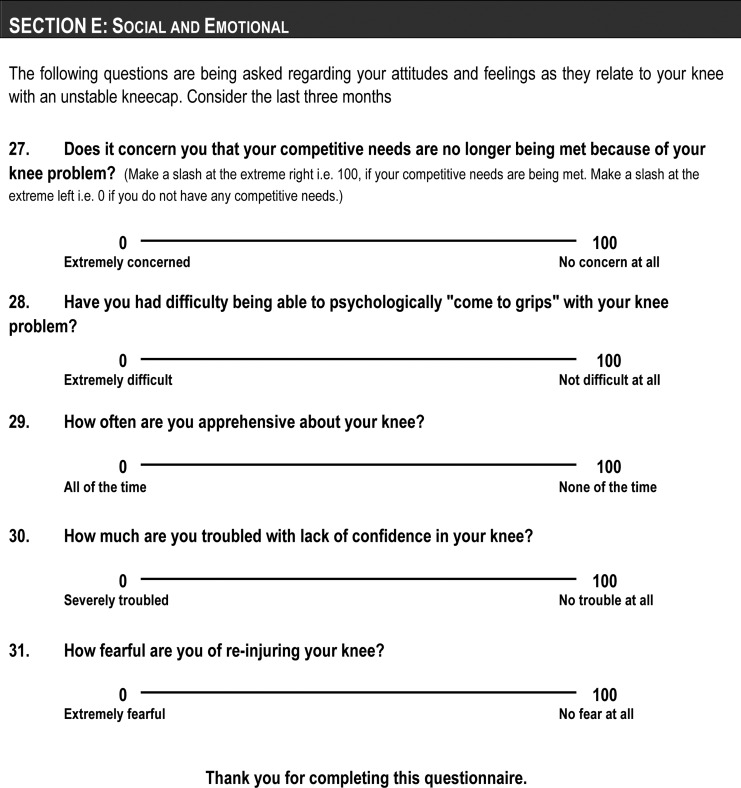

The Banff Patellar Instability Instrument (BPII) was first published and its initial validity and reliability reported in July 2013 (see the Appendix).4 The BPII is a quality-of-life score comprising 32 questions within 5 domains, including symptoms and physical complaints; work-related concerns; sport, recreation, and competition; lifestyle; and social and emotional. By including these domains, the BPII is designed to capture a more holistic view of the quality of life of patients with patellofemoral instability. A modified Ebel procedure was utilized, with a group of international experts identifying the most important outcome measure questions for the new disease-specific quality-of-life tool, to establish initial content validity.6,7 A total of 150 completed BPIIs were used to evaluate validity and reliability. The BPII study reported on the initial validity and reliability in both patellofemoral instability and post–patellofemoral stabilization populations as a measure of quality of life. In addition, initial responsiveness and concurrent validity were reported.

The BPII and NPI are both recently developed tools that attempt to fill the void of disease-specific outcome measures for patellofemoral instability identified by Smith et al15 in 2008. As a quality-of-life measure, the BPII assesses a broad set of constructs providing a holistic view of patients’ outcomes. In comparison, the NPI measures exclusively the physical domain. The Kujala score measures patellofemoral pain, symptoms, and function. The Kujala score is commonly employed for patellar instability outcome assessment in the literature; however, only 1 of the 13 questions asks about symptoms of instability.

Validity is an iterative process and therefore, no single study will determine whether an instrument is valid and reliable.14,18 However, as additional research is completed on an instrument, in different or more broad populations, the results build toward greater validity.9,19 In keeping with the COSMIN validity domain, content, criterion, and construct validity all require evaluation to demonstrate the quality of a patient-reported outcome. Concurrent validity is a component of criterion validity.12 The primary purpose of this study was to assess the concurrent validity of the BPII to the NPI score and the Kujala score in patients with patellofemoral instability.

Methods

Population/Sample

Between February 2013 and November 2013, a total of 85 patients referred with patellar instability underwent an initial assessment by an orthopaedic surgeon at a tertiary sports medicine clinic with a subspecialization in patellofemoral instability. All patients were referred by sports medicine physicians and had failed nonoperative management. Each patient underwent a standardized knee-specific history and physical examination along with plain radiographic imaging. The orthopaedic surgeon confirmed the diagnosis of recurrent patellofemoral instability in 78 patients via history, clinical examination of lateral patellar laxity and apprehension, assessment of risk factors, and plain radiographs. The study sample was 72% female and 28% male, with a mean age of 24.7 ± 8.8 years (range, 13-43 years). All patients were asked to complete the BPII, NPI, and Kujala scores at the time of their initial consultation. The 3 outcomes measures were provided to the patients in a random order. The study received ethics approval from the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board and Child Health Research Office.

Statistical Considerations

A Pearson r correlation coefficient was computed using SPSS (version 17.0; IBM Corp) to determine the relationship between each of the patient-reported outcomes (BPII, NPI, and Kujala scores). The total score was used for each instrument. In addition, a physical function subset was calculated for the BPII (BPII-physical). Items 1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 11, 19, 20, and 22 were assessed as belonging within the “physical” construct or domain due to the focus of these questions being about level of function. This series of BPII questions was selected in an effort to provide a more direct comparison to the NPI, which is exclusively focused on physical symptoms. Each item in the BPII is measured on a 100-mm visual analog scale, and these items were summated and then converted to a score out of 100. The resulting BPII-physical score was used as an additional comparison with the NPI score and the Kujala score.

Results

Seventy-four patients completed all items on the BPII, NPI, and Kujala questionnaires, and these data were analyzed. Descriptive statistics for the BPII, BPII-physical, NPI, and Kujala scores are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Comparison of the BPII, NPI, and Kujala Scoresa

| Outcome Measure | Sample Size | Mean ± SDb |

|---|---|---|

| BPII | 74 | 25.1 ± 13.93 |

| BPII-physical | 74 | 29.16 ± 15.52 |

| NPI | 74 | 43.50 ± 22.76 |

| Kujala | 74 | 53.16 ± 19.54 |

aBPII, Banff Patella Instability Instrument; NPI, Norwich Patellar Instability.

bOutcome measures were determined out of maximum score of 100.

There were statistically significant correlations between the BPII and the NPI score (r = –0.53 [95% CI, 0.34-0.68]; P < .001) as well as the BPII and the Kujala score (r = 0.50 [95% CI, 0.30-0.66]; P < .001). There were also significant correlations between the subset of BPII-physical items and both the NPI score (r = –0.57 [95% CI, 0.39-0.71]; P < .001) and the Kujala score (r = 0.58 [95% CI, 0.40-0.72]; P < .001), as well as significant correlation between the NPI score and the Kujala score (r = 0.50 [95% CI, 0.30-0.66], P < .001).

Discussion

This study provides additional validation of the BPII via concurrent validation to the NPI. Tool development is an iterative process and ongoing validation is essential to ensure the methodological soundness of the outcome measure.19 This study demonstrated a moderately strong correlation between the BPII and the NPI, which are both designed to evaluate patients who present with patellofemoral instability. The BPII also demonstrated a moderately strong correlation to the Kujala. The most important aspect of any outcome measure is ensuring that it is measuring what it is intended to measure. The assessment of a relationship between the patient-reported outcomes assessed in this study provides evidence that they are measuring similar although not exactly the same constructs.

Disease-specific outcome measures for patellofemoral instability can have different purposes, with some focused on purely physical complaints and others assessing quality of life as a whole. Both types of measures will have their place in the analysis of outcomes in this challenging patient population. The BPII is a quality-of-life measure, where the higher the score (out of 100) the better the patient’s quality of life. The NPI is a measure of patellofemoral instability, so the higher the score the greater the degree of disability. The negative correlation evident between the BPII and NPI in this study is due to the inverse nature of the scales. The statistically significant correlation between these 2 outcome measures demonstrates the tools are measuring some of the same constructs, although there remains some variability, likely secondary to the distinct purpose of each tool.

Because the BPII measures a broad range of quality-of-life constructs in comparison with the NPI, which measures physical symptoms and function, it follows that the BPII-physical score demonstrated a stronger correlation with the NPI than the total BPII score. Further research assessing the 5 constructs of the BPII via factor analysis will be necessary to confirm these constructs as well as the number of items that fall under the physical symptoms domain. Despite the Kujala scale including only 1 question specific to instability of the patella, the BPII and the NPI both correlated moderately strongly with the Kujala score, indicating that these outcome measures have other areas of overlap. In the context of the COSMIN guidelines, all 3 of these patient-reported outcomes used for patellofemoral instability require further research. The relationship of the standard deviation of each score to measurement precision in the patellar instability population also merits investigation. It is possible that the narrower standard deviation demonstrated by the BPII score is indicative of the instrument’s ability to more precisely measure patient-reported outcomes.

Specific to patellofemoral instability, the Kujala score was originally evaluated in a population of 34 subjects.5 The face validity, content validity, and aspects of structural validity were reported; however, the reliability and responsiveness of the score were not assessed. The initial face and content validation and internal consistency assessment of the NPI addressed 2 criteria of instrument development.16 The primary intent of the NPI is related to the physical function of patients who suffer from patellofemoral instability, and therefore, it does not include other dimensions or domains commonly measured in disease-specific, health-related quality-of-life instruments.3 The initial validity and reliability of the BPII was established in keeping with the COSMIN guidelines.11,12 Face, content, criterion, and construct validity were reported in the original publication.4 Responsiveness to change of the BPII was measured in a patellofemoral instability population that proceeded to a stabilization procedure. The reliability of the BPII was assessed in the areas of internal consistency and test-retest reliability. The BPII is the first of these outcome measures to be validated in both the pre- and postsurgical population, and it is the only instrument to measure quality of life in patellofemoral instability patients.4

Limitations of this study include the narrow focus on 1 aspect of outcome measure validation: concurrent validity. It is important to note that completing research in all 9 COSMIN checklist areas would be almost impossible in a single study. As such, various components of outcome measure development need to be addressed in separate studies, and some of these will require a single purpose. All patients included in this study had failed nonoperative management and therefore may not represent the full range of patients with recurrent patellar instability. The broad range of pathoanatomic characteristics of patients presenting with patellofemoral instability make this heterogeneous population challenging to analyze. This may account for the broad standard deviations seen in the current patient-reported outcome measures.

There are also a number of other studies that are required for the BPII to complete the full COSMIN checklist. In keeping with the iterative nature of outcome measure development, ongoing validity, reliability, and responsiveness testing are required for a health-related tool to be considered high quality. Testing these important factors of the BPII will be essential across a number of studies, and with new patients, to build greater scientific soundness. It is important that similar standards are applied to both newly developed outcome measures such as the BPII and established measures such as the Kujala score to ensure that the same level of evidence exists for the use of these tools in patellofemoral instability outcomes research.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated a moderately strong correlation of the BPII to existing outcome measures that are used to evaluate patients with patellofemoral instability. This study adds further validity to the BPII in accordance with the COSMIN guidelines. The steps undertaken in this study are in keeping with high-quality instrument development, and future studies will continue to enhance the clinimetric and psychometric quality of the BPII.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the support of colleagues Drs S. Mark Heard and Gregory M. Buchko along with the staff of the Banff Sport Medicine Clinic.

Appendix

The Banff Patella Instability Instrument

Footnotes

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: Banff Sport Medicine has received funding from Lifemark Canada, Sanofi Canada, Covenant Health, and ConMed Linvatec Canada. L.A.H. has received speaking fees from ConMed Linvatec.

References

- 1. Berwick DM. Medical associations: guilds or leaders? BMJ. 1997;314:1564–1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fithian DC, Paxton EW, Stone ML, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of acute patellar dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1114–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:622–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hiemstra LA, Kerslake S, Lafave MR, Heard SM, Buchko GM, Mohtadi NG. Initial validity and reliability of the Banff Patella Instability Instrument. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:1629–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kujala UM, Jaakkola LH, Koskinen SK, Taimela S, Hurme M, Nelimarkka O. Scoring of patellofemoral disorders. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lafave M, Katz L, Butterwick D. Development of a content-valid standardized orthopedic assessment tool (SOAT). Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2008;13:397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lafave MR, Katz L, Donnon T, Butterwick DJ. Initial reliability of the Standardized Orthopedic Assessment Tool (SOAT). J Athl Train. 2008;43:483–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mehta VM, Inoue M, Nomura E, Fithian DC. An algorithm guiding the evaluation and treatment of acute primary patellar dislocations. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2007;15:78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Messick S. Validity of psychological assessment: validation of inferences from persons’ responses and performances as scientific inquiry into score meaning. Am Psychol. 1995;50:741–749. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Gibbons E, et al. Inter-rater agreement and reliability of the COSMIN (COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement Instruments) checklist. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:539–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:737–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nomura E, Inoue M. Second-look arthroscopy of cartilage changes of the patellofemoral joint, especially the patella, following acute and recurrent patellar dislocation. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:1029–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Norman GR, Wyrwich KW, Patrick DL. The mathematical relationship among different forms of responsiveness coefficients. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:815–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smith TO, Davies L, O’Driscoll ML, Donell ST. An evaluation of the clinical tests and outcome measures used to assess patellar instability. Knee. 2008;15:255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith TO, Donell ST, Clark A, et al. The development, validation and internal consistency of the Norwich Patellar Instability (NPI) score. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22:324–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stefancin JJ, Parker RD. First-time traumatic patellar dislocation: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Streiner DL. A checklist for evaluating the usefulness of rating scales. Can J Psychiatry. 1993;38:140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use. 4th ed New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, Ostelo RW, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:651–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]