Abstract

Background

Overall prescribing of benzodiazepines and z-hypnotics (B&Zs) has slowly reduced over the past 20 years. However, long-term prescribing still occurs, particularly among older people, and this is at odds with prescribing guidance.

Aim

To compare prescribing of B&Zs between care home and non-care home residents ≥65 years old.

Design and setting

Cross-sectional population-based study in primary care in Scotland.

Method

National patient-level B&Z prescribing data, for all adults aged ≥65 years, were extracted from the Prescribing Information System (PIS) for the calendar year 2011. The PIS gives access to data for all NHS prescriptions dispensed in primary care in Scotland. Data were stratified by health board, residential status, sex, and age (65–74, 75–84, and ≥85 years). To minimise disclosure risk, data from smaller health boards were amalgamated according to geography, thereby reducing the number from 14 to 10 areas.

Results

A total of 17% (n = 879 492) of the Scottish population were aged ≥65 years, of which 3.7% (n = 32 368) were care home residents. In total, 12.1% (n = 106 412) of older people were prescribed one or more B&Z: 5.9% an anxiolytic, 7.5% a hypnotic, and 1.3% were prescribed both. B&Zs were prescribed to 28.4% (9199) of care home and 11.5% (97 213) of non-care home residents (relative risk = 2.88, 95% CI = 2.82 to 2.95, P<0.001). Estimated annual B&Z exposure reduced with increasing age of care home residents, whereas non-care home residents’ exposure increased with age.

Conclusion

B&Zs were commonly prescribed for older people, with care home residents approximately three times more likely to be prescribed B&Zs than non-care home residents. However, overall B&Z exposure among non-care home residents was found to rise with increasing age.

Keywords: anxiolytics, benzodiazepines, care homes, family practice, hypnotics, older people

INTRODUCTION

Benzodiazepine and z-hypnotic (B&Z) prescribing remains an issue across the US, Australasia, and Europe.1–6 Although benzodiazepine prescribing has reduced and z-hypnotic prescribing has increased over the past 20 years,3,4,7 their use in clinical practice remains controversial. Inappropriate prescribing results in long-term chronic use,8 particularly among older people, which is of concern and is contrary to previous and current advice.9

B&Zs demonstrate only marginal benefits for short-term relief of insomnia and some anxiety disorders,10–12 and are not recommended for management of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia.13,14 Their use is further limited by problems with tolerance, dependence, and other adverse effects.10–12 These include increased falls that double the risk of hip fracture;10,15,16 cognitive impairment and associated dementia risks;10,17,18 depressive symptoms;19,20 and paradoxical effects such as disinhibition, anxiety, and impulsivity.21 Given the limited benefits and substantial risks associated with their use, B&Zs should be avoided in older people. Unfortunately, these risks may have been overshadowed by the recent focus on antipsychotic use in dementia and in care homes. As antipsychotics ‘appear to be used too often in dementia’ across the UK, North America, and parts of Europe, at current levels of prescribing they may cause more harm than good to older people with dementia.22

In Scotland between 2001 and 2011, the number of people aged ≥65 years increased by 11%. Four per cent of the Scottish population aged ≥65 years reside in care homes, of whom 97% are long-term residents. Fifty per cent of residents have a formal diagnosis of dementia and a further 9% have an informal diagnosis of dementia.23,24 Previous UK and international studies indicate that up to 33% of people ≥65 years may be prescribed B&Zs, and that older people with dementia are twice as likely to be prescribed these drugs, with care home residents being two to three times more likely.25–29 These studies were largely conducted at a regional level and were possibly influenced by local policy, drug availability, and routine practice. The current study, however, aims to compare B&Z prescribing between care home and non-care home residents aged ≥65 years, at regional and national levels across Scotland.

METHOD

The UK NHS is taxpayer funded and devolved in the home nations. NHS Scotland is organised into 14 health boards covering a population of 5.3 million people across a land mass of 30 414 square miles, ranging from highly rural to highly urbanised areas, with large variations in socioeconomic deprivation. All NHS patients in Scotland are assigned a Community Health Index (CHI) number that acts as a unique identifier and provides information on sex and date of birth.30 Linkage to other datasets can provide further information such as care home residency status. The national Prescribing Information System (PIS) contains information on all NHS prescriptions dispensed in the community, of which over 95% include the patient’s CHI number.31

How this fits in

Inappropriate benzodiazepine and/or z-hypnotic use remains a major concern among older people. This study sheds light on benzodiazepine and z-hypnotic prescribing among care home and non-care home residents, and appears to be contrary to previous and currently accepted guidance, and good clinical practice. Further work is required towards minimising benzodiazepine and/ or z-hypnotic drug use for older people, especially for care home residents.

The care home population was estimated from the PIS by counting individuals dispensed any prescription and flagged, based on their registered address, as being a care home resident. The non-care home population was estimated by subtracting the care home population from National Records of Scotland population estimates for 2010, the most recently available at the time of data extraction.

Any person aged ≥65 years with at least one B&Z dispensed during the calendar year 2011 was identified with data extracted from the PIS. The data output was aggregated to number of patients stratified by sex, age group (65–74 years, 75–84 years, and ≥85 years), and care home residency status. The data included number of patients, number of prescriptions, and amount of drug dispensed; the latter was expressed as the World Health Organization ‘defined daily doses’. Defined daily doses provide a standardised method to compare prescribing volumes between organisations.32 To correct for known differences between defined daily doses and health board formulary variation across Scotland, diazepam-equivalent doses were calculated from individual B&Z defined daily doses,9,33 allowing the estimated annual B&Z exposure to be calculated.

Information was extracted at national and health board levels for individual B&Zs and grouped as either an anxiolytic or a hypnotic as classified in Chapter 4 of the British National Formulary.9 Because of small numbers in some data categories, and to minimise disclosure risk, data from the smaller health boards were amalgamated according to similarity in geography and proximity, reducing 14 health boards to 10 ‘health board areas’.

Descriptive analysis was performed to identify differences in B&Z prescribing between and within the care home and non-care home populations by health board area, sex, age ranges, and drugs prescribed. Short-acting and long-acting drug effects were also considered in line with STOPP/ START (Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions/Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment) criteria.34 The estimated average annual B&Z exposure, expressed as diazepam equivalents per day for care home and non-care home residents by age category, were also calculated, but statistical tests were not applied because of the small number of aggregated data points. Data were collated using Microsoft Excel and further analysed using SPSS (version 19).

RESULTS

A total of 17% (n = 879 492) of the population in Scotland were aged ≥65 years, of whom 3.7% (n = 32 368) were care home residents. Care home residents were more likely to be female (χ2 = 3131, degrees of freedom [df] = 1, P<0.001) and aged ≥85 years (χ2 = 57 307, df = 2, P<0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic details of study population

| Population 2011 (aged ≥65 years) | Care home, n (%) | Non-care home, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 32 368 (3.7) | 847 124 (96.3) |

|

| ||

| Age, years | ||

| 65–74 | 3846 (11.9) | 470 011 (54.2) |

| 75–84 | 11 372 (35.1) | 287 659 (33.2) |

| ≥85 | 17 150 (53.0) | 89 454 (10.3) |

|

| ||

| Female | 23 447 (72.4) | 480 873 (56.8) |

Overall, 12.1% (n = 106 412) of those aged ≥65 years were prescribed one or more B&Z, with 5.9% (n = 52 320) prescribed only an anxiolytic, 7.5% (n = 65 911) only a hypnotic, and 1.3% (n = 11 819) were prescribed both. However, 28.4% (n = 9199) of care home residents and 11.5% (n = 97 213) of non-care home residents were prescribed one or more B&Z, with care home residents significantly more likely to be prescribed a B&Z (χ2 = 8416, df = 1, P<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

B&Z prescribed for the Scottish population aged ≥65 years

| Drugs prescribed | Care home n (% of respective population) | Non-care home n (% of respective population) |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiolytic and/or hypnotic | 9199 (28.4) | 97 213 (11.5) |

| Female | 6575 (28.0) | 66 175 (13.8) |

| Male | 2624 (29.4) | 31 038 (8.0) |

|

| ||

| Age, years | ||

| 65–74 | 1297 (33.6) | 48 594 (10.3) |

| 75–84 | 3541 (31.1) | 35 974 (12.5) |

| ≥85 | 4361 (25.4) | 12 645 (14.1) |

|

| ||

| Anxiolytic | 5565 (17.2) | 46 755 (5.5) |

| Female | 3974 (16.9) | 32 745 (6.8) |

| Male | 1591 (17.8) | 14 010 (3.8) |

|

| ||

| Age, years | ||

| 65–74 | 905 (23.4) | 25 974 (5.5) |

| 75–84 | 2265 (19.9) | 16 191 (5.6) |

| ≥85 | 2395 (14.0) | 4590 (5.1) |

|

| ||

| Hypnotic | 5051 (15.6) | 60 860 (7.2) |

| Female | 3589 (15.3) | 40 838 (8.5) |

| Male | 1462 (16.4) | 20 022 (5.5) |

|

| ||

| Age, years | ||

| 65–74 | 615 (15.9) | 28 214 (6.0) |

| 75–84 | 1864 (16.4) | 23 446 (8.2) |

| ≥85 | 2572 (15.0) | 9200 (10.3) |

|

| ||

| Both an anxiolytic and hypnotic | 1417 (4.4) | 10 402 (1.2) |

|

| ||

| Choice of drug | % of prescriptions | % of prescriptions |

|

| ||

| Anxiolytics | ||

| Lorazepam (S) | 49.9 | 15.6 |

| Diazepam (L) | 46.6 | 77.0 |

| Others: chlordiazepoxide (L) or oxazepam (L) | 3.8 | 7.4 |

|

| ||

| Hypnotics | ||

| Zopiclone (S) | 52.9 | 39.0 |

| Temazepam (S) | 33.7 | 36.6 |

| Nitrazepam (L) | 6.6 | 13.6 |

| Zolpidem (S) | 5.5 | 9.5 |

| Others: loprazolam (S), lormetazepam (S) or zaleplon (S) | 1.3 | 1.3 |

B&Z = benzodiazepines and z-hypnotics. L = long-acting drug. S = short-acting drug

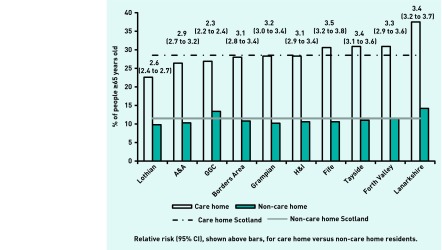

There were small but significant variations in the proportion of care home and non-care home residents prescribed B&Zs at health board level (χ2 = 238, df = 9, P<0.001; and χ2 = 1986, df = 9, P<0.001, respectively) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion and relative risk of B&Z prescribing in older people according to residential status. A&A = Ayrshire and Arran. Borders area = Dumfries and Galloway, and Borders health boards. GGC = Greater Glasgow and Clyde. H&I = Highland health board and those of the islands including Western Isles, Orkney, and Shetland.

In total, 28.4% of care home residents were prescribed B&Zs compared with 11.5% of non-care home residents. The national relative risk of being prescribed a B&Z was 2.88 (95% CI = 2.82 to 2.95, P<0.001), ranging from 2.3 (95% CI = 2.3 to 2.4, P<0.001) to 3.5 (95% CI = 3.2 to 3.8, P<0.001) across ‘health board areas’ for care home residents (Figure 1).

Male care home residents were more likely than female care home residents to be prescribed B&Zs (χ2 = 5.978, df = 1, P<0.0145). However, males not in care homes were significantly less likely than females to be prescribed B&Zs (χ2 = 5720, df = 1, P<0.001).

Care home residents aged ≥85 years were significantly less likely than younger care home residents to be prescribed B&Zs (χ2 = 167, df = 2, P<0.001). Conversely, B&Z use increased with increasing age among non-care home residents (χ2 = 1521, df = 2, P<0.001). The shorter-acting B&Zs accounted for a larger proportion of B&Zs prescribed in care homes, for example, the short-acting anxiolytic lorazepam in preference to diazepam and the very short-acting hypnotic zopiclone in preference to short-acting temazepam and long-acting nitrazepam.

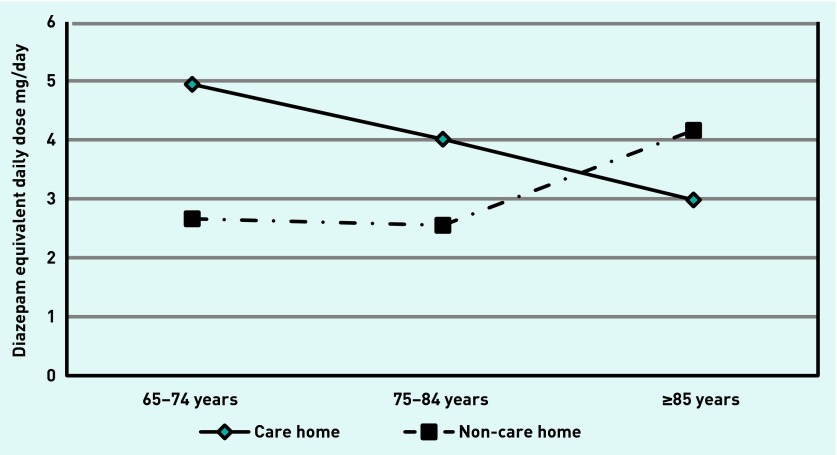

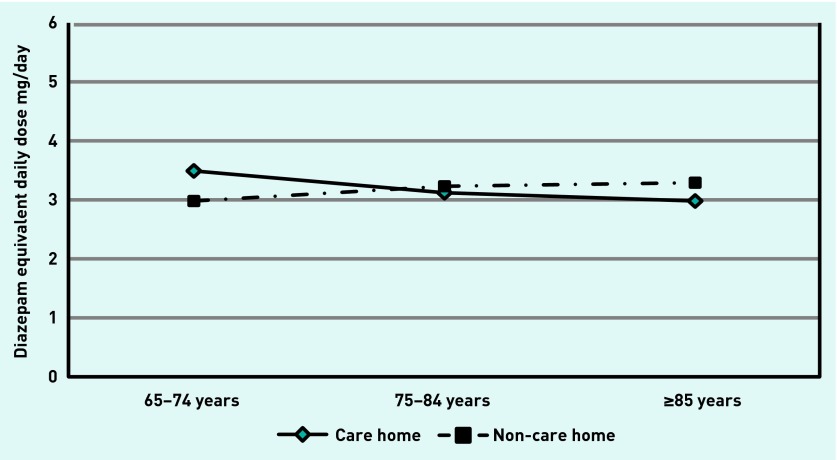

The estimated average annual B&Z exposure, expressed as diazepam equivalents per day, was higher among care home residents aged 65–74 years than among non-care home residents of the same age, with diazepam-equivalent daily dose of anxiolytic being 4.9 mg versus 2.7 mg, and 3.5 mg versus 3 mg daily for hypnotics, respectively, for care home and non-care home residents. However, the estimated average annual B&Z exposure appeared to reduce with increasing age for care home residents while showing the opposite trend among non-care home residents (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Estimated average annual anxiolytic exposure by age group.

Figure 3.

Estimated average annual hypnotic exposure by age group.

DISCUSSION

Summary

This study has shown that a large proportion of older people in Scotland are commonly prescribed B&Zs. Those that reside in care homes are three times more likely to be prescribed one or more B&Zs than those not living in care homes.

Male care home residents were more likely than female residents to be prescribed B&Zs whereas the opposite was observed among non-care home residents. The estimated average annual B&Z exposure appeared to reduce with increasing age of care home residents, unlike those not living in care homes where doses appear to increase with increasing age.

Strengths and limitations

The national PIS dataset allowed investigation of routine patient-level prescribing by analysing prescriptions dispensed in the community, thus enabling differences in regional and national prescribing to be identified. As PIS data are CHI linked, demographic and residential information was also used to identify differences in prescribing between different cohorts at regional and national level. This study demonstrates the utility of PIS data in identifying prescribing issues within specific patient groups. This allows and informs the targeting of resources for medication reviews, and local and national prescribing initiatives to support safe and effective medicines use to minimise drug risks, such as B&Z-associated falls and/or negative cognitive effects.

It was not possible to explore variations in individual care home data or individuals’ prescription dosages. However, more personalised data are available for health boards and approved researchers. As with other studies of this nature, the lack of information on drug indications linked to prescribing is a limiting factor,1,2,27–29,35 but details of prescription indications in patients’ clinical notes are known to be incomplete or lacking.24 This may improve with the introduction of the Scottish Primary Care Resource (SPIRE), a collaboration between the Scottish Government and NHS National Services Scotland to simplify and standardise the process for extracting data from GP practice systems for audit, disease surveillance, benchmarking, planning, and research.36 Correcting for age and sex, analysis of the estimated average annual B&Z exposure was also limited due to data being categorised and aggregated prior to release and further analysis, therefore future studies should consider using anonymised patient-level data. The cross-sectional study design limits the assessment of drug succession and dose trajectory over time, and for those dispensed multiple anxiolytics or hypnotics, or combinations of both. It was not possible to determine if these drugs were co-dispensed or dispensed at different time points throughout the year. However, previous studies have demonstrated that a similar proportion of non-care home residents were prescribed combination B&Zs,1 with long-term prescribing a common feature.8 Finally, as with all database studies, the PIS captures dispensing information and not actual drug administration so compliance with B&Z treatment is unknown.

Comparison with existing literature

The findings that 3.7% of those aged ≥65 years were care home residents is comparable with other UK studies, which found similar rates of 4.1% and 3.7%, and of residents being predominately female and older.27,35

This study’s observation that 12.1% of people ≥65 years old were prescribed one or more B&Zs, that is, one in four of the care home population and one in nine of the non-care home residents, with care home residents approximately three times more likely to have a B&Z prescribed, is also comparable to the wider literature,2,25,27–29,37 but is lower than that found among a Canadian sample.1

This study found anxiolytic prescribing for non-care home residents to be comparable with previous studies.27,35,37 However, for care home residents it was almost twice as high as previously reported.27,35 Hypnotic prescribing was also comparable with previous studies for non-care home residents,27,35 and with care home residents in one study,27 but significantly lower than the 26.6% observed in another study.35 These differences may be due to regional prescribing variations,38 as the other studies also focused on care home and non-care home residents in the UK.

Contrary to previous observations, there was no increase in the proportion of care home residents prescribed hypnotics with increasing age,1 although, in line with previous UK and non-UK studies, the proportion of non-care home residents prescribed hypnotics did increase with increasing age.1–3,37 Conversely, the estimated average annual B&Z exposure by age category appeared to reduce for care home residents with increasing age. This may partially account for lower hip fracture rates in care homes,16 as higher B&Z doses are associated with a higher risk of falls.15 However, this is a complex area with multiple factors influencing individual falls and fracture risks.

Implications for research and practice

This study highlights, at a national and regional level, that a large proportion of people ≥65 years are still prescribed B&Zs, even though their clinical utility is questionable and their use is related to many risks in older people.10,15–21 Despite this, B&Zs continue to be widely used, especially among care home residents who tend to be older and frailer, and more susceptible to their adverse drug effects.

A greater proportion of shorter-acting B&Zs are prescribed in care homes, which may reflect prescribers’ efforts to minimise adverse effects. However, short-acting and long-acting B&Zs demonstrate a similar falls risk.16,39 The use of higher B&Z doses further increases falls risk,15 which may be more problematic for non-care home residents due to the observed higher B&Z exposure with increasing age. Short-acting B&Zs are also more commonly associated with disinhibition,14,40 which is likely to cause additional problems in a care home environment and is a concern where z-hypnotic prescribing has increased.

The variations in prescribing prevalence between health board areas may be due to differences in regional and local prescribing guidance and formulary choices; deprivation; population served; prescriber characteristics; general practice prescribing support activities; care home staff and patient characteristics; and availability of specialist care home services.28,38,41,42 Greater Glasgow and Clyde is ranked third lowest for care home prescribing but second highest for non-care home prescribing. This suggests that specialist care home services operating within the board may have had some effect on B&Z prescribing. Conversely, other health boards that also provide specialist care home services appear to have higher B&Z use. Rurality does not appear to be associated with lower prescribing as Lothian is highly urbanised, yet shows the lowest prescribing prevalence for both care home and non-care home residents. However, within all health board areas there are prescribing variations with some practices prescribing more B&Zs than others, which will also be true for care homes.38

This exploratory study demonstrates the utility of using data routinely available from the PIS to identify prescribing issues at a national and regional level. The use of the PIS data will enable national, regional, and local services to target resources to achieve reductions in inappropriate prescribing of psychoactive medications in line with guidance and policy, for example, the Scottish Government’s Dementia Strategy.43 It will also enable clinicians to identify high-priority patients for regular medication review in line with national polypharmacy guidance.44 The presence of CHI within the PIS provides the ability to link multiple prescription events for an individual and also to link this data to other datasets, such as hospital admissions data relating to falls. In the future, the PIS could potentially link prescribing information with the SPIRE dataset to relevant comorbidities,36 further improving the utility of databases to improve the targeting of resources to improve patient care.

Future research should consider the complex issues that account for regional and local prescribing variations. Qualitative approaches have a role in exploring prescribing variations between and within care homes and general practices.

In Scotland the development of the PIS national dataset with the potential to link prescribing data to general practice, hospital admission, and other health datasets creates huge potential for audit, disease surveillance, benchmarking, planning, and research to improve current services and work towards better outcomes for service users.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Professor Graham Jackson, Alzheimer Scotland Professor of Dementia, University of the West of Scotland, for reviewing and commenting on the manuscript for this study.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as this study was considered to be service evaluation. However, Information Services Division Scotland of NHS National Services Scotland provided Caldicott Guardian approval for the data to be used. The National Research Ethics Service guidelines indicate that for this type of data analysis an Institutional Review Board approval is not necessary.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Tu K, Mamdani MM, Hux JE, Tu JB. Progressive trends in the prevalence of benzodiazepine prescribing in older people in Ontario, Canada. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(10):1341–1345. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(2):136–142. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hollingworth SA, Siskind DJ. Anxiolytic, hypnotic and sedative medication use in Australia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(3):280–288. doi: 10.1002/pds.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKean A, Vella-Brincat J. Ten-year dispensing trends of hypnotics in New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2011;124(1331):108–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knapp M, McDaid D, Mossialos E, Thornicroft G, editors. Mental health policy and practice across Europe: the future direction of mental health care. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sonnenberg CM, Bierman EJ, Deeg DJ, et al. Ten-year trends in benzodiazepine use in the Dutch population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(2):293–301. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0344-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Information Services Division Scotland Prescribing and medicines: medicines used in mental health. http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Prescribing-and-Medicines/Publications/data-tables.asp?id=1146#1146 (accessed 17 Mar 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donoghue J, Lader M. Usage of benzodiazepines: a review. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2010;14(2):78–87. doi: 10.3109/13651500903447810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joint Formulary Committee . British national formulary. 67th edn. London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glass J, Lanctot KL, Herrmann N, et al. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta-analysis of risks and benefits. BMJ. 2005;331(7526):1169. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38623.768588.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults: management. London: NICE; 2011. CG113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baldwin DS, Anderson IM, Nutt DJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(6):567–596. doi: 10.1177/0269881105059253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network . Management of patients with dementia. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2006. SIGN 86. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor D, Paton C, Kapur S, editors. The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. 11th edn. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterke CS, van Beeck EF, van der Velde N, et al. New insights: dose-response relationship between psychotropic drugs and falls: a study in nursing home residents with dementia. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52(6):947–955. doi: 10.1177/0091270011405665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cumming RG, Le Couteur DG. Benzodiazepines and risk of hip fractures in older people: a review of the evidence. CNS Drugs. 2003;17(11):825–837. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200317110-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallacher J, Elwood P, Pickering J, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: evidence from the Caerphilly Prospective Study (CaPS) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(10):869–873. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Billioti de Gage S, Moride Y, Ducruet T, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: case-control study. BMJ. 2014;349:g5205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rickels K, Case WG, Schweizer E, et al. Long-term benzodiazepine users 3 years after participation in a discontinuation program. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):757–761. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kripke DF. Greater incidence of depression with hypnotic use than with placebo. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dell’osso B, Lader M. Do benzodiazepines still deserve a major role in the treatment of psychiatric disorders? A critical reappraisal. Eur Psychiatry. 2013;28(1):7–20. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banerjee S. The use of antipsychotic medication for people with dementia: time for action. London: Department of Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Records of Scotland Statistical bulletin 21 March 2013. 2011 census: First results on population and household estimates for Scotland — release 1B. 2013. http://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/documents/censusresults/release1b/rel1bsb.pdf (accessed 17 Mar 2016)

- 24.Information Services Division Scotland Care home census 2011: additional findings on adult residents in care homes in Scotland. 2012. Feb 28, http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Health-and-Social-Community-Care/Care-Homes/Previous-Publications/index.asp (accessed 17 Mar 2016)

- 25.Craig D, Passmore AP, Fullerton KJ, et al. Factors influencing prescription of CNS medications in different elderly populations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2003;12(5):383–387. doi: 10.1002/pds.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guthrie B, Clark SA, McCowan C. The burden of psychotropic drug prescribing in people with dementia: a population database study. Age Ageing. 2010;39(5):637–642. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCowan C, Magin P, Clark SA, Guthrie B. An observational study of psychotropic drug use and initiation in older patients resident in their own home or in care. Age Ageing. 2013;42(1):51–56. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Svarstad BL, Mount JK. Chronic benzodiazepine use in nursing homes: effects of federal guidelines, resident mix, and nurse staffing. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(12):1673–1678. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.t01-1-49278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruths S, Sorensen PH, Kirkevold O, et al. Trends in psychotropic drug prescribing in Norwegian nursing homes from 1997 to 2009: a comparison of six cohorts. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(8):868–876. doi: 10.1002/gps.3902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Information Services Division Scotland CHI. http://www.ndc.scot.nhs.uk/Dictionary-A-Z/Definitions/index.asp?Search=C&ID=128&Title=CHI (accessed 17 Mar 2016)

- 31.Information Services Division Scotland Prescribing Information System for Scotland. http://www.isdscotland.scot.nhs.uk/Health-Topics/Prescribing-and-Medicines/Prescribing-Datamarts/#prisms (accessed 17 Mar 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization DDD: Definition and general considerations. http://www.whocc.no/ddd/definition_and_general_considera/ (accessed 17 Mar 2016)

- 33.Ashton H. Benzodiazepines: how they work and how to withdraw (the Ashton Manual) http://www.benzo.org.uk/manual/index.htm (accessed 17 Mar 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, et al. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment). Consensus validation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;46(2):72–83. doi: 10.5414/cpp46072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maguire A, Hughes C, Cardwell C, O’Reilly D. Psychotropic medications and the transition into care: a national data linkage study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):215–221. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.NHS Scotland Scottish Primary Care Information Resource. www.spire.scot.nhs.uk (accessed 17 Mar 2016)

- 37.Taylor S, McCracken CF, Wilson KC, Copeland JR. Extent and appropriateness of benzodiazepine use. Results from an elderly urban community. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:433–438. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.5.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsimtsiou Z, Ashworth M, Jones R. Variations in anxiolytic and hypnotic prescribing by GPs: a cross-sectional analysis using data from the UK Quality and Outcomes Framework. Br J Gen Pract. 2009 doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X420923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Vries OJ, Peeters G, Elders P, et al. The elimination half-life of benzodiazepines and fall risk: two prospective observational studies. Age Ageing. 2013;42(6):764–770. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olson LG. Hypnotic hazards: adverse effects of zolpidem and other z-drugs. Australian Prescriber. 2008;31(6):146–149. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson C, Thomson A. Prescribing support pharmacists support appropriate benzodiazepine and Z-drug reduction 2008/09: experiences from North Glasgow. Clin Pharm. 2010;3(Suppl 1):S5–S6. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greater Glasgow Primary Care NHS Trust Annual report enhanced services: nursing homes medical practice Report and recommendations. 2005 Dec; http://library.nhsggc.org.uk/mediaAssets/Hidden%20Storage/nhsggc_care_homes_report_recommendations_2005-12.pdf (accessed 17 Mar 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scottish Government Scotland’s National Dementia Strategy 2013–16. http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Health/Services/Mental-Health/Dementia/DementiaStrategy1316 (accessed 17 Mar 2016)

- 44.NHS Scotland Polypharmacy guidance 2012. http://www.central.knowledge.scot.nhs.uk/upload/Polypharmacy%20full%20guidance%20v2.pdf (accessed 17 Mar 2016)