Abstract

Background

Hip fracture is often complicated by depressive symptoms in older adults. We sought to characterize trajectories of depressive symptoms arising after hip fracture and examine their relationship with functional outcomes and walking ability. We also investigated clinical and psychosocial predictors of these trajectories.

Method

We enrolled 482 inpatients, aged ≥60 years, who were admitted for hip fracture repair at eight St Louis, MO area hospitals between 2008 and 2012. Participants with current depression diagnosis and/or notable cognitive impairment were excluded. Depressive symptoms and functional recovery were assessed with the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale and Functional Recovery Score, respectively, for 52 weeks after fracture. Health, cognitive, and psychosocial variables were gathered at baseline. We modeled depressive symptoms using group-based trajectory analysis and subsequently identified correlates of trajectory group membership.

Results

Three trajectories emerged according to the course of depressive symptoms, which we termed ‘resilient’, ‘distressed’, and ‘depressed’. The depressed trajectory (10% of participants) experienced a persistently high level of depressive symptoms and a slower time to recover mobility than the other trajectory groups. Stressful life events prior to the fracture, current smoking, higher anxiety, less social support, antidepressant use, past depression, and type of implant predicted membership of the depressed trajectory.

Conclusions

Depressive symptoms arising after hip fracture are associated with poorer functional status. Clinical and psychosocial variables predicted membership of the depression trajectory. Early identification and intervention of patients in a depressive trajectory may improve functional outcomes after hip fracture.

Keywords: Depression, functional recovery, hip fracture, mobility, older adults, trajectory

Introduction

Falls are the leading cause of hip fractures in older adults (Parkkari et al. 1999). Hip fractures are disabling medical events (Zuckerman, 1996; Hannan et al. 2001; Magaziner et al. 2003; Bentler et al. 2009) and their recovery is often complicated with depressive symptoms and pain (Holmes & House, 2000b; Williams et al. 2006). Depressive symptoms are associated with the risk of falling, functional impairment, and failure to regain walking independence after hip fracture (Mossey et al. 1990; Lenze et al. 2004; Givens et al. 2008; Morghen et al. 2011). Recovery of walking ability is crucial for patients to regain independence, partake in the community, and reintegrate into their environment (Salpakoski et al. 2014).

Despite these adverse depression-linked outcomes, depression tends to be unrecognized when it emerges after hip fracture (Müller-Thomsen et al. 2002). Most studies after hip fracture have focused on the prevalence of depressive symptoms, thus including a mix of new-onset cases and chronic illness cases (Mossey et al. 1990; Holmes & House, 2000a, b; Shyu et al. 2009). To our knowledge, only two studies have reported exclusively on depressive symptoms developing post-fracture (Lenze et al. 2007; Oude Voshaar et al. 2007). These studies found that apathy, sub-threshold depressive symptoms, anxiety, cognitive impairment, pain, and history of depression were risk factors for incident depression. Questions remain about how depressive symptoms evolve in the longer term after hip fracture and whether additional variables are associated with new-onset depressive symptomology. Proper assessment of new-onset depressive symptoms post-fracture and correlates thereof could help identify patients at risk and subsequently allow interventions to mitigate a decline in functional status (Lenze et al. 2004; Bentler et al. 2009), alleviate the burden of disability (Lenze et al. 2001), and improve quality of life (Ormel et al. 2002).

We recently concluded a longitudinal clinical epidemiologic study to investigate genetic polymorphisms predictive of depressive symptoms arising post-fracture (Rawson et al. 2015). The study design included in-depth psychosocial and clinical evaluations over 1 year's time post-fracture focusing exclusively on patients not experiencing a depressive episode when the fracture occurred. We therefore constructed a group-based trajectory model to fit depressive symptoms post-fracture and examined how these trajectories correlate with post-operative outcomes in the year following fracture. The group-based trajectory approach creates a practical summary of longitudinal data by recognizing patterns that develop over time. We hypothesized that higher depression scores would correlate with poorer recovery of daily living activities and mobility and worse pain ratings post-fracture. To determine the most relevant correlates of depressive symptomology after hip fracture, we examined covariates that have been shown in previous studies to contribute to depressive symptoms in older adults including lifetime vulnerability health-related factors [medical illness (Lenze et al. 2007; Sutin et al. 2013), history of depression (Oude Voshaar et al. 2007), antidepressant use (Lenze et al. 2007; Sutin et al. 2013), cognition (Oude Voshaar et al. 2007; Kim et al. 2012), smoking (Kim et al. 2012; Heyes et al. 2015)]; psychosocial factors [exposure to stressful events (Devanand et al. 2002), anxiety symptoms (Oude Voshaar et al. 2007), social support (George et al. 1989)]; pre-fracture functioning [mobility (Mossey et al. 1990; Lenze et al. 2004)]; and characteristics of the fracture [fracture type (Lenze et al. 2007; Kim et al. 2012), implant type (Bentler et al. 2009; Tseng et al. 2012), pain (Oude Voshaar et al. 2007; Denkinger et al. 2014; Petrovic et al. 2014)].

Method

Participants

We recruited participants with a primary diagnosis of hip fracture admitted for surgical correction at eight area hospitals in St Louis, MO between 2008 and 2012. Participants aged ≥60 years were screened for inclusion. Key exclusion criteria were non-ambulatory prior to fracture, current diagnosis of major or minor depressive disorder (i.e. were clinically depressed at time of fracture), and non-transient moderate to severe cognitive impairment (per chart review and brief bedside cognitive testing). Additional exclusions were metastatic cancer, interferon treatment, inoperable fracture, significant language, visual or hearing impairment, lived more than 1 h away, or inability to consent or cooperate with study protocol. All participants signed a written informed consent approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and the local hospital's review board.

Participants were followed for 52 weeks with the initial baseline assessment approximately 2 days post-surgery. Assessments were done at scheduled intervals (1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 26, and 52 weeks) after the initial baseline visit. Baseline, week 4, and week 52 assessments were conducted in person while assessments at weeks 1, 2, 8, 12, and 26 were performed over the phone. Trained study personnel performed all assessments.

Measures

Depression

The Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; Montgomery & Asberg, 1979) was the primary depression measure. Initial MADRS scores assessed depressive symptoms pre-fracture, as hospitalized patients described their mood during the week prior to fracture. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV disorders (SCID-IV; First et al. 1996) diagnosed major and minor depressive disorder date of onset. The SCID was administered at the initial visit to assess depressive disorder at time of fracture and lifetime history of depressive disorder. Additionally, if the MADRS score was ≥10 or if the reported sadness or anhedonia item was ≥2 at any follow-up visit, participants were assessed with the SCID for new-onset depressive disorder.

Functional recovery

Basic activities of daily living (BADLs), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), and mobility were assessed with the Functional Recovery Score (FRS) from the Hospital for Joint Diseases Geriatric Hip Fracture Research Group (Zuckerman et al. 2000). Participants were asked how much help they needed with several activities using a scale of 0 (cannot do activity at all) to 4 (no help needed). Mobility was rated on a scale of 0–4 (0, non-ambulatory or transfers only; 1, cannot walk outdoors, can walk at home with assistive devices; 2, cannot walk outdoors, can walk at home without assistive devices; 3, can walk outdoors with assistive devices; 4, can walk outdoors without assistive devices. These scores were summed and scaled for each section (BADLs, IADLs, mobility) for a total FRS number ranging from 0 to 100. The FRS was obtained at the initial baseline visit to collect pre-fracture functioning, and weeks 4, 12, 26, and 52 to monitor post-fracture functioning. Participants’ use of assistive devices (e.g. cane or walker) and ambulatory status (community ambulator, household ambulator, non-ambulatory) were also documented at each visit. Information about the type of fracture and implant was collected at baseline. Fracture type was classified as (1) femoral neck, (2) intertrochanteric, or (3) subtrochanteric/other. Type of implant consisted of (1) total hip arthroplasty or hemiarthroplasty, (2) internal fixation with screws, or (3) sliding hip screw, intramedullary (IM) nail, or other.

Pain

At all time points, participants used a numerical rating scale with a score of 0 indicating no pain and 10 the worst pain (Jensen & Karoly, 1992).

Psychosocial

Stressful life events experienced during the year prior to fracture were assessed with the Geriatric Adverse Life Events Scale (GALES; Devanand et al. 2002). The scale consists of a checklist of 21 adverse life events and the degree of stress of each event was rated on a three-point scale: (1, not at all; 2, somewhat; 3, very stressful). Scores were summed for a total stress score (maximum of 63), with higher scores indicating a higher degree of stress.

The Duke Social Support Index (DSSI; Landerman et al. 1989) was administered at the initial visit to evaluate four different dimensions of social support: (1) size of social network, (2) social interaction, a four-item index measuring the frequency of interaction with members of their network, (3) subjective support, a six-item scale measuring the participant's perception of their inclusion as a valued and useful member of the social network and the participant's perceived satisfaction with social support received, and (4) instrumental support, a 13-item index listing tangible services received from the participant's support network.

Anxiety was measured by summing three items (tense, worried, relaxed) selected from the brief version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – State (STAI-S; Berg et al. 1998). At the initial visit, participants used a five-point scale to rate the extent they have felt these emotions during the past 24 h (1, not at all; 2, a little; 3, moderately; 4, quite a bit; 5, extremely). The remaining three items of the brief version (steady, strained, comfortable) were not included due to similar wording with other (non-anxiety) symptoms experienced by older adults after fracture.

Cognitive

The Short Blessed Test (SBT) evaluated baseline cognitive status (Katzman et al. 1983). Higher scores indicate more cognitive difficulties. Participants were excluded if they had a previous diagnosis of dementia or showed moderate to severe cognitive impairment on the SBT (score >12), that did not resolve by the end of their surgical repair hospitalization.

During the initial hospitalization, we also ensured absence of delirium symptoms using interviewer's observations, chart records, and the Delirium Rating Scale (DRS; Trzepacz & Dew, 1995).

Health

The Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics (CIRS-G) evaluated medical illness burden (Miller et al. 1992). The scale quantifies medical data from chart reviews and participant interviews. Fourteen bodily systems are rated on a 0–4 scale [0, no problem; 1, mild problem; 2, moderate severity problem; 3, severe disability; 4, extremely severe problem (e.g. acute hip fracture would be rated 4)]. Ratings are then tallied for a total score. Medication usage was also documented at the initial visit. Two dichotomous variables were created to indicate antidepressant and/or psychotropic use. History of smoking was collected at baseline and smoking status was classified as (1) current, (2) past, or (3) never smoked.

Living

At all time points, the participant's place of residence was recorded as living at home or a type of facility (e.g. skilled nursing facility).

Statistical analysis

Trajectory modeling

In this study, we employed group-based trajectory modeling to characterize depressive symptoms after hip fracture. The procedure proc traj, (SAS 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., USA) utilizes semi-parametric maximum likelihood estimation to cluster participants into groups that follow similar progressions of latent trajectories over time without inferring zones of rarity. A series of quadratic models were run that allowed evaluation of an increasing number of trajectories and the removal of higher order non-significant slopes in order to determine the number of trajectories that best characterized our sample over time. Model specification included a zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) distribution to fit the positively skewed data, review of alphas to determine the inflation function for each trajectory (e.g. intercept, linear, or quadratic zero-inflation probability logit, usual Poisson model), and starting points accounting for the initial, pre-fracture MADRS scores. Careful model selection included clinician interpretation, group sizes >5%, and use of Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) values to compare competing models with different number of trajectories and polynomial functions. Participants were assigned to a specific trajectory, using the highest probability of membership, once the model was correctly specified. Individuals with probabilities <0.70 were excluded in aid of correct classification (Nagin & Odgers, 2010). The resulting group membership was then used in the following analyses including ANOVAs for percent of functioning and mobility recovered and examination of variables obtained at the initial visit (i.e. χ2 for categorical variables, ANOVAs for continuous variables).

Multinomial logistic model (MLN)

Trajectory group membership was the dependent variable. Independent variables included in the final model were age, gender, CIRS-G, antidepressant use, smoking history, pain ratings, SBT cognitive status, FRS mobility scores, GALES stress ratings, DSSI subscales, anxiety symptoms, history of minor/major depression, and implant type. Inclusion of these variables was based on previous research supporting a variable's importance, ensuring variables were not redundant, improvement in model fit, an interpretable MLN coefficient in terms of sign, size, and significance, and/or a significant independent ANOVA or χ2 test. Continuous variables were centered to improve interpretation of log odds.

Generalized estimating equation (GEE)

GEE was used to model the repeated pain assessments. SAS procedure genmod with a normal distribution, log link, and unstructured covariance structure was specified to examine the main effect of time, trajectory group, and the interaction between time and group.

Survival analysis

The log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test compared if the survival curves were identical among the three trajectory groups in regards to likelihood of returning home post-fracture. For the living arrangements analysis, only participants who lived at home at the time of fracture were included. Participants were considered uncensored if they returned home at a particular time point during the study. Participants that did not return home were censored and time to home was recorded as their last available data time point. Survival analysis was calculated using the product limit (Kaplan–Meier) method with GraphPad Prism v. 6.05 for Windows (GraphPad Software, USA).

Results

Identification of trajectories: resilient, distressed, and depressed

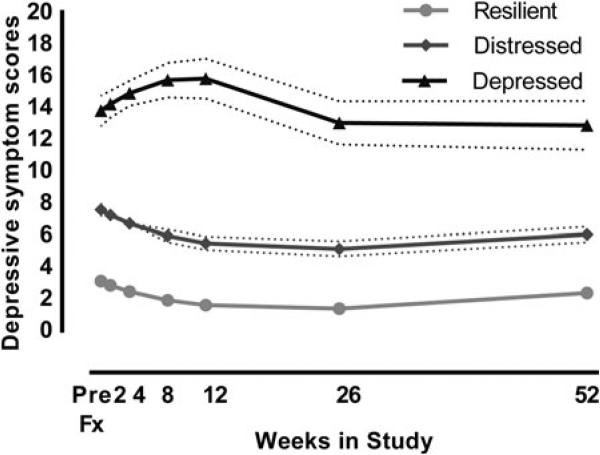

Table 1 presents statistics on demographics, mobility, health, hospitalization, psychosocial, cognition, and recovery for all participants and by the identified trajectory groups. Twenty-three participants were not included in the trajectory model due to missing data on the MADRS at baseline and an additional 29 participants were excluded because their probability of membership to one group was <0.70. The group-based trajectory analysis implied three typical patterns of depressive symptoms emerging during the year post-fracture, which we named ‘resilient’, ‘distressed’, and ‘depressed’ (Fig. 1). The resilient trajectory consisted of 223 (51.8%) participants who exhibited a very low level of depressive symptoms throughout the study period. The distressed trajectory included 164 (38.1%) participants, who had an initial increase in depressive symptoms during the first month post-fracture that gradually subsided to levels similar to pre-fracture scores. The depressed trajectory consisted of 43 (10%) participants who experienced a high level of depressive symptoms throughout the study. Specifically, this group had an elevation of depressive symptoms at week 1 that increased further to a threshold typical of clinical depression in older adults (MADRS ≥15) between weeks 1 and 8 and remained high for the remainder of the year.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of study sample and for the different trajectory groups

| Trajectory group |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 430) | Resilient (n = 223) | Distressed (n = 164) | Depressed (n = 43) | p | Post-hoc a | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, years, mean (s.d.) | 78.2 (8.8) | 78.5 (8.4) | 78.2 (8.9) | 76.5 (10.1) | 0.40 | |

| Education, years, mean (s.d.) | 13.2 (2.9) | 13.2 (2.9) | 13.0 (2.8) | 13.6 (3.0) | 0.46 | |

| Gender, n (% female) | 325 (75.8) | 168 (75.3) | 123 (75.0) | 34 (79.1) | 0.85 | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| Caucasian | 403 (93.7) | 208 (93.2) | 155 (94.5) | 40 (93.0) | 0.67 | |

| African American | 24 (5.6) | 12 (5.4) | 9 (5.5) | 3 (7.0) | ||

| Asian | 3 (0.7) | 3 (1.4) | – | – | ||

| Living arrangement, n (%)b | ||||||

| Home | 412 (95.8) | 215 (96.4) | 157 (95.7) | 40 (93.0) | 0.52 | |

| Rehab, SNF, ALF | 18 (4.2) | 8 (3.6) | 7 (4.3) | 3 (7.0) | ||

| Mobility | ||||||

| Ambulatory status, n (%)c | ||||||

| Community ambulator | 403 (93.9) | 211 (95.5) | 153 (93.3) | 39 (90.7) | 0.42 | |

| Household ambulator | 26 (6.1) | 11 (5.0) | 11 (6.7) | 4 (9.3) | ||

| Assistive devices, n (%)c | ||||||

| No assistive device | 311 (72.5) | 165 (74.3) | 120 (73.2) | 26 (60.5) | 0.23 | |

| Use cane | 61 (14.2) | 33 (14.9) | 19 (11.6) | 9 (20.9) | ||

| Use walker | 57 (13.3) | 24 (10.8) | 25 (15.2) | 8 (18.6) | ||

| Health | ||||||

| CIRS-G co-morbidities, mean (s.d.) | 12.6 (3.7) | 11.9 (3.5) | 13.3 (3.8) | 13.7 (4.1) | <0.001 | Dep/Dis > R |

| Antidepressant use, n (% yes) | 88 (20.7) | 36 (16.4) | 35 (21.3) | 17 (40.5) | 0.002 | Dep > Dis/R |

| Antipsychotic use, n (% yes) | 99 (23.3) | 47 (21.5) | 41 (25.0) | 11 (26.2) | 0.65 | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||||

| Current | 51 (11.9) | 18 (8.1) | 23 (14.1) | 10 (23.3) | 0.02 | Dep > Res |

| Past | 208 (48.5) | 105 (47.1) | 83 (50.9) | 20 (46.5) | ||

| Never | 170 (39.6) | 100 (44.8) | 57 (35.0) | 13 (30.2) | ||

| Hospitalization | ||||||

| Days to surgery, mean (s.d.) | 1.6 (1.7) | 1.8 (1.7) | 1.5 (1.8) | 1.2 (0.7) | 0.07 | |

| Length of stay, mean (s.d.) | 5.5 (4.8) | 5.0 (2.2) | 5.7 (5.6) | 7.3 (8.6) | 0.02 | Dep > Dis/R |

| Type of fracture, n (%) | ||||||

| Femoral neck fracture | 218 (51.4) | 121 (55.0) | 84 (52.2) | 13 (30.2) | 0.02 | Dep < Dis/R |

| Intertrochanteric | 165 (38.9) | 76 (34.5) | 66 (41.0) | 23 (53.5) | ||

| sub-trochanteric and other | 41 (9.7) | 23 (10.5) | 11 (6.8) | 7 (16.3) | ||

| Type of surgery, n (%) | ||||||

| Total hip/hemiarthroplasty | 172 (40.2) | 96 (43.4) | 67 (40.9) | 9 (20.9) | 0.02 | Dep < Dis/R |

| Internal fixation with screws | 101 (23.6) | 57 (25.8) | 31 (18.9) | 13 (30.2) | ||

| Otherd | 155 (36.2) | 68 (30.8) | 66 (40.2) | 21 (48.9) | ||

| Emotion-related assessments | ||||||

| Anxiety traitse,f | ||||||

| Relaxed, mean (s.d.) | 3.3 (1.2) | 3.0 (1.1) | 3.5 (1.2) | 3.7 (1.1) | <0.001 | Dep/Dis > R |

| Worried, mean (s.d.) | 2.3 (1.3) | 1.9 (1.1) | 2.6 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.2) | <0.001 | Dep > Dis > R |

| Tense, mean (s.d.) | 2.3 (1.3) | 1.9 (1.1) | 2.6 (1.3) | 3.0 (1.4) | <0.001 | Dep > Dis > R |

| Duke social support Index | ||||||

| Instrumental support, mean (s.d.) | 9.9 (2.1) | 10.0 (2.0) | 9.9 (2.2) | 9.4 (2.0) | 0.30 | |

| Social interaction, mean (s.d.) | 6.3 (2.4) | 6.5 (2.4) | 6.2 (2.4) | 5.7(2.0) | 0.12 | |

| Social network, mean (s.d.) | 5.3 (4.2) | 5.2 (4.2) | 5.3 (4.2) | 5.5 (4.5) | 0.91 | |

| Subjective support, mean (s.d.) | 10.3 (2.0) | 9.9 (1.6) | 10.5 (2.1) | 11.5 (2.9) | <0.001 | Dep > Dis > R |

| GALES stress rating, mean (s.d.)g | 2.7 (2.9) | 2.0 (2.4) | 3.1 (3.0) | 4.5 (3.6) | <0.001 | Dep > Dis > R |

| MADRS, mean (s.d.)h | 3.2 (4.4) | 1.5 (2.0) | 4.6 (4.8) | 7.4 (6.7) | <0.001 | Dep > Dis > R |

| History of depression, n (% yes)i | 61 (14.4) | 17 (7.7) | 30 (18.4) | 14 (35.0) | <0.001 | Dep/Dis > R |

| Cognition | ||||||

| Short Blessed Test, mean (s.d.) | 4.6 (3.3) | 4.3 (3.3) | 4.9 (3.2) | 5.2 (3.5) | 0.07 | |

| Recovery assessments | ||||||

| Functional Recovery Score | ||||||

| BADL score, mean (s.d.) | 43.7 (1.8) | 43.7 (1.6) | 43.5 (2.3) | 44.0 (0.0) | 0.27 | |

| IADL score, mean (s.d.) | 21.4 (3.0) | 21.6 (3.1) | 21.2 (3.1) | 21.0 (2.3) | 0.25 | |

| Mobility score, mean (s.d.) | 30.9 (3.8) | 31.2 (3.6) | 30.8 (3.6) | 29.8 (5.1) | 0.08 | |

| Total score, mean (s.d.) | 96.0 (6.8) | 96.5 (6.6) | 95.5 (7.1) | 94.8 (6.6) | 0.16 | |

| Pain rating scale, mean (s.d.)j | 3.3 (2.8) | 2.9 (2.8) | 3.4 (2.8) | 4.3 (2.5) | 0.01 | Dep > Dis/R |

ALF, Assisted living facility; BADLs, basic activities of daily living; CIRS-G, Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics; Dep, Depressed trajectory group; Dis, Distressed trajectory group; IADLs, instrumental activities of daily living; GALES, Geriatric Adverse Life Events Scale; MADRS, Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale; R, resilient; Rehab, rehabilitation facility; s.d., standard deviation; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Significant χ2 tests were further evaluated to compare cell counts using a z test and Bonferroni correction.

Place of residence at time of fracture.

Participants reported on their pre-fracture functional status.

Other: sliding hip screw, intramedullary nail or specific implant.

Participants reported on their emotions for the past 24 h.

For relaxed, high scores reflect less anxiety; for tense and worried, high scores reflect high anxiety.

Participants reported on adverse life events in the year prior to fracture.

Participants reported on their mood in the week prior to fracture.

Clinical interview to determine past major or minor depression disorder.

Participants reported on their pain levels during the past 24 h.

Fig. 1.

Trajectories of depressive symptoms, measured with Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale, after hip fracture using group-based trajectory modeling. Three clusters of individuals following similar patterns of depressive symptoms emerging during the year post-fracture were classified in the initial sample of 459 (resilient 50.7%, distressed 39.3%, depressed 10.0%). The depressed group experienced a persistently high number of depressive symptoms throughout the study period. Predicted estimates with 95% confidence intervals are shown. Model specification included a quadratic zero-inflated probability (ZIP) logit for the resilient group, an intercept only ZIP logit for the distressed group, and a typical Poisson function for the depressed group.

There were 50 (22.4%) participants clinically diagnosed with new-onset major or minor depression after the initial baseline visit. Of these, participants were more likely to be in the depressed (42.0%) or the distressed (56.0%) trajectory groups than the resilient trajectory group [2.0%, χ2 = 30.18 (2), p ≤0.001].

Baseline variables associated with trajectory group membership

Results from the multinomial logistic model (Table 2) shows that health and emotion-related characteristics obtained at baseline account for part of the differences between trajectory groups (pseudo-R2 = 0.32, p < 0.001). Compared to the resilient group, on average, the depressed group had 38% higher GALES stressful life-event ratings, 49% higher anxiety, and was 39% less satisfied with subjective support. The depressed group was also 3.6 times more likely to be taking anti-depressants, three times more likely to have a history of major or minor depression, 4.1 times more likely to be a current smoker (reference group: never smoked), and 6.9 times more likely to have a sliding hip screw/IM nail/other type of surgical implant (reference group: total hip arthroplasty/hemiarthroplasty) compared to the resilient group. The distressed group, relative to the resilient group, had 10% higher CIRS-G scores, 15% higher GALES ratings, 25% higher anxiety ratings, and 11% poorer SBT cognitive scores. Additionally, the distressed group was 1.3 times more likely to have a history of depression, 1.7 times more likely to be a current smoker, and 1.1 times more likely to have a surgical repair consisting of sliding hip screw/IM nail/other implant in relation to the resilient group.

Table 2.

Estimated odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) from multinomial logistic regression of trajectory groups

| Estimate | s.e. | Pr > χ2 | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distressed v. resilient | |||||

| Intercept | –1.42 | 0.48 | 0.003 | 0.24 | |

| Age, years | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.06 |

| Antidepressant use | 0.07 | 0.37 | 0.85 | 1.07 | 0.52–2.23 |

| Anxiety traits | 0.22 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 1.25 | 1.13–1.38 |

| CIRS-G co-morbidities | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1.10 | 1.02–1.20 |

| FRS Mobility score | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 0.93–1.08 |

| GALES stress rating | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 1.15 | 1.04–1.28 |

| Gender | –0.19 | 0.33 | 0.55 | 0.83 | 0.44–1.56 |

| History of depression | 0.85 | 0.43 | 0.05 | 2.33 | 1.00–5.42 |

| Implant type – internal fixation with screws | –0.31 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.73 | 0.36–1.48 |

| Implant type – sliding hip screw, IM nail, other | 0.76 | 0.32 | 0.02 | 2.14 | 1.13–4.03 |

| Pain rating scale | –0.05 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.96 | 0.86–1.06 |

| SBT cognitive score | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1.11 | 1.02–1.21 |

| Smoking status – current | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.05 | 2.71 | 1.01–7.29 |

| Smoking status – past | 0.50 | 0.32 | 0.11 | 1.65 | 0.89–3.06 |

| Social network | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 1.05 | 0.98–1.12 |

| Subjective support | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 1.11 | 0.95–1.29 |

| Depressed v. resilient | |||||

| Intercept | –5.01 | 0.99 | <0.001 | 0.01 | |

| Age | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.24 | 1.04 | 0.98–1.10 |

| Antidepressant use | 1.53 | 0.59 | 0.01 | 4.61 | 1.46–14.61 |

| Anxiety traits | 0.40 | 0.09 | <0.001 | 1.49 | 1.25–1.78 |

| CIRS-G co-morbidities | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.45 | 1.05 | 0.92–1.20 |

| FRS mobility score | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.81 | 1.02 | 0.89–1.17 |

| GALES stress rating | 0.32 | 0.09 | <0.001 | 1.38 | 1.17–1.64 |

| Gender | –0.94 | 0.60 | 0.11 | 0.39 | 0.12–1.26 |

| Implant type – internal fixation with screws | 1.01 | 0.65 | 0.12 | 2.75 | 0.77–9.77 |

| Implant type – sliding hip screw – IM nail, other | 2.07 | 0.63 | 0.001 | 7.94 | 2.31–27.31 |

| History of depression | 1.39 | 0.65 | 0.03 | 4.02 | 1.13–14.28 |

| Pain rating scale | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.33 | 1.09 | 0.92–1.30 |

| SBT cognitive score | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.42 | 1.07 | 0.91–1.24 |

| Smoking status – current | 1.63 | 0.79 | 0.04 | 5.11 | 1.09–24.00 |

| Smoking status – past | 0.51 | 0.59 | 0.39 | 1.67 | 0.52–5.31 |

| Social network | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 1.09 | 0.98–1.22 |

| Subjective support | 0.33 | 0.11 | 0.003 | 1.39 | 1.12–1.72 |

CIRS-G, Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics; FRS, Functional Recovery Score; GALES, Geriatric Adverse Life Events Scale; IM, intramedullary; SBT, Short Blessed Test.

Reference categories for categorical variables are antidepressant use (none), gender (male), history of depression (no), and smoking status (never smoker), implant type (total hip arthroplasty, hemiarthroplasty).

Likelihood ratio χ2 statistic (d.f.) = 117.23, p < 0.001 (32), AIC = 525.77, R2 = .32 (Cox & Snell), 0.38 (Nagelkerke adjusted value). Each parameter is independent of the other variables. n = 305.

Post-fracture variables associated with trajectory group membership

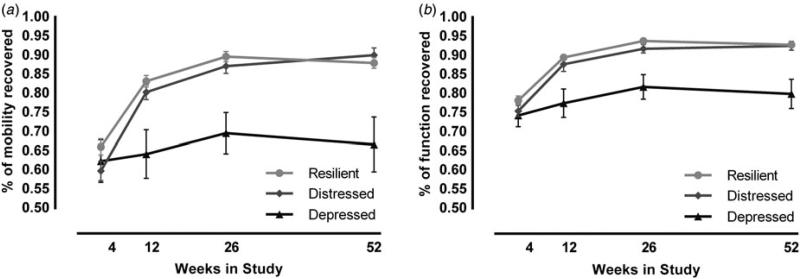

Recovery of mobility

Using the mobility scaled scores from the FRS, we estimated the percent of mobility recovered from their pre-fracture mobility scores [(follow-up week/pre-fracture) × 100] to examine how the groups recovered (Fig. 2a). At 12 weeks’ post-fracture, the depressed group had recovered to only 64% of their pre-fracture mobility score, whereas the resilient group had recovered to 83% (F2,360 = 9.1, p < 0.001). Similarly, at 1-year post-fracture, the depressed group recovered to only 67% of their pre-fracture mobility score, whereas the resilient group recovered to 88% (F2,327 = 13.64, p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Depressed trajectory associated with poorer mobility and functional recovery. Assessment of whether participants returned to pre-fracture functioning was estimated as the percent recovered at each time point relative to pre-fracture scores [(follow-up week/pre-fracture) × 100]. Both percent of (a) mobility recovered and (b) total functional recovery indicated significant differences between the depressed and resilient groups at weeks 12, 26, and 52. Figures display means with standard error bars for each time point.

Overall functional recovery

We found similar results using the percent of total FRS score, which includes not only mobility but also BADLs and IADLs, relative to pre-fracture total FRS (Fig. 2b). At 12 weeks’ post-fracture, the depressed group had recovered to only 77% of their pre-fracture function, whereas the resilient group had recovered to 89% (F2,360 = 9.6, p < 0.001). Similarly, at 1-year post-fracture, the depressed group recovered to only 80% of their pre-fracture total FRS, whereas the resilient group recovered to 93% (F2,327 = 12.0, p < 0.001).

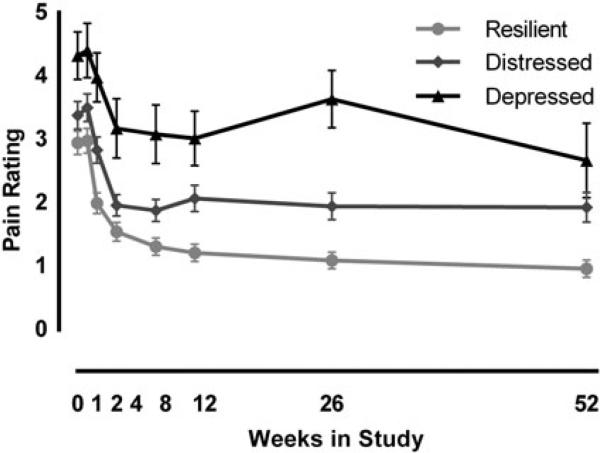

Pain

The depressed trajectory group reported more pain than the resilient and distressed groups throughout the study. Results from the GEE model found a signifi-cant main effect of time (), main effect of trajectory group (), and a time×group interaction (), indicating participants in the depressed group reported more overall pain and more persistence of pain than the resilient group (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Depressed trajectory associated with higher pain. Repeated measures of pain ratings, using generalized estimating equations, revealed a significant time, group, and time×group interaction. Estimated means with standard error bars are shown.

Secondary outcomes

Supplementary Table S1 illustrates additional outcomes of mobility, living arrangements, and mortality. At 1-year post-fracture, the depressed trajectory group were less likely to be independent of assistive devices than the resilient group and more likely to use a wheel-chair or be non-ambulatory than the distressed and resilient groups (). Likewise, a lower proportion of participants in the depressed group reported they were able to walk in the community than participants in the resilient and distressed groups (). In regard to participants who lived at home at the time of fracture and were able to return home during the study period, we found no differences between trajectory groups (), nor between survival curves when examining time to home (log rank = 0.6, p = 0.41). Mortality did not differ between trajectory groups ().

Discussion

In this large sample of patients with hip fracture, we characterized patterns of new-onset depressive symptoms during the year post-fracture. Our data suggested three clusters of participants based on the course of emergent depressive symptoms: the ‘resilient’ group who showed no intense distress, the ‘distressed’ group who exhibited a small but transient rise, and the ‘depressed’ group who experienced high levels of depressive symptoms. Next, we examined which clinical and psychosocial variables were associated with more depressive symptoms and found the depressed trajectory could be distinguished from the resilient group by several health and psychosocial variables collected at the initial visit. Last, we found the depressed trajectory was less likely to recover to their pre-fracture mobility scores and had higher levels of pain throughout the study compared to the distressed and resilient groups.

The study's repeated depressive symptom assessments during the year post-fracture allowed us to observe longitudinal patterns of depressive symptoms that develop after a medical stressor. As depression can go unrecognized post-surgery (Müller-Thomsen et al. 2002), we examined which baseline variables could be characterized as risk factors for developing a depressive trajectory post-fracture. High anxiety, history of stressful life events, less satisfaction with subjective support, antidepressant use, being a current smoker, past clinical diagnosis of major or minor depression, and implant type were found to differentiate the depressed group and resilient group in our study. Among these early indicators of a depressive trajectory, several of them support previous findings. For instance, more anxiety was identified as a risk factor for being in the depressive trajectory, replicating a prior report by Oude Voshaar et al. (2007). A history of depressive illness has also been correlated with development of depression post-fracture (Lenze et al. 2007; Oude Voshaar et al. 2007). Higher stress levels experienced with adverse life events in the year prior to fracture predicted membership in the depression trajectory. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report this association in this setting although it is consistent with research indicating depression often develops in the context of multiple, cumulative stressful life events (Kendler et al. 1999; Brown et al. 2014; Swartz et al. 2014).

Our results also demonstrated that participants who followed the depressive trajectory exhibited worse functional and mobility outcomes in the post-operative repeated measures. The depressed group had the lowest percentage of pre-fracture function recovered, in terms of both mobility and total functional recovery, of the three trajectory groups throughout most of the study period. As can be expected, percent of mobility and total function recovered was low for all three groups 4 weeks after fracture. At 3 months post-fracture, however, the depressed group saw little improvement in mobility, whereas both the distressed and resilient groups had recovered to 80% of their pre-fracture mobility. Additionally, a greater proportion of participants in the depressed group were non-ambulatory or required assistive devices 1-year post-fracture, indicating greater dependence and mobility disability in this group. Our findings agree with previous literature showing depressive symptoms are associated with poor rehabilitation outcomes, loss of independence (Mossey et al. 1990; Holmes & House, 2000b; Lenze et al. 2004; Hershkovitz et al. 2007; Tseng et al. 2012), and failure to regain walking ability after hip fracture rehabilitation (Mossey et al. 1990; Givens et al. 2008; Morghen et al. 2011). Likewise, our findings echo prior evidence of poor functional recovery in patients with depressive symptoms in other clinical settings such as stroke and cardiac rehabilitation (Herrmann et al. 1998; Swardfager et al. 2011).

Another important finding was the progression of pain over time in the depressed trajectory. In contrast to Petrovic et al. (2014), who reported higher post-operatory pain after hip arthroplasty in patients with depressive symptoms, we observed that pain ratings were similar among the three trajectories in the immediate post-operatory period. However, differences in pain became evident over time with the depressed group exhibiting higher pain than the distressed and resilient groups the remainder of the year. Overall, this finding adds to existing literature indicating a close association between pain and depression (Williamson & Schulz, 1992; Karp et al. 2005; Morone et al. 2010; Jackson, 2013; Denkinger et al. 2014). It is also possible that pain could have interfered with recovery in the depressive trajectory group, as higher levels of pain have been associated with poorer function after hip fracture (Williams et al. 2006; Salpakoski et al. 2014).

The poorer functional recovery scores and higher pain ratings imply participants in the depressed group experienced a higher burden of disability after hip fracture. In this regard, several studies have shown an association between depression and disability in older adults (Kennedy et al. 1990; Zeiss et al. 1996; Beekman et al. 1997; Prince et al. 1997; Penninx et al. 1999; Lenze et al. 2001; Ormel et al. 2002). Our research group has previously reported the rapid onset of depressive symptoms is a common event during acute-care hospitalization (Lenze et al. 2007). It has also been postulated that depressed patients are less physically active (Penninx et al. 1999) and participate less in rehabilitation programs, impeding their functional recovery (Feinstein, 1999; Lenze et al. 2004; Swardfager et al. 2011). The findings also call attention to the difficulty in discerning causal inference in an observational study, as it may be that persistent disability and pain led to persistently elevated depressive symptomology.

Unique study strengths include our prospective design, the systematic measurement of depressive symptoms immediately after hip fracture, and the long-term, comprehensive battery of clinical and psychosocial assessments. In addition, study participants were assessed free of depressive illness, delirium, and moderate-severe cognitive impairment at the beginning of the study which allowed us to more accurately examine the trajectory course of emergent depressive symptoms after hip fracture.

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting this study's results. First, information about falls was not included. Given that falls are associated with depression (Kvelde et al. 2013; Stubbs et al. 2016) and a history of falls is associated with poor outdoor walking recovery (Salpakoski et al. 2014) we could not adequately explore confounding effects related to falls in our results. Second, mobility was assessed using the participant's self-report from the FRS at all time points. An objective measure such as the Timed ‘Up & Go’ test (Podsiadlo & Richardson, 1991) could have provided a more precise estimation of mobility. Third, the use of the numerical pain rating scale limited our ability to explore different aspects of pain. In future research we would consider using the Brief Pain Inventory (Cleeland & Ryan, 1994), which assesses pain intensity and interference with activities.

In conclusion, three trajectories of depressive symptoms – resilient, distressed, and depressed – were specified using group-based trajectory modeling. Focusing on the depressed trajectory, this group, comprising 10% of participants with hip fracture, had poorer recovery of mobility, poorer functional recovery, and higher ratings of pain in the year following hip fracture. The necessity of walking ability and functional recovery to regaining independence after hip fracture underlines the importance of our findings (Salpakoski et al. 2014). As well, several clinical and psychosocial variables were identified which could be potentially useful variables in delineating who is at greatest risk for developing a depressive trajectory after hip fracture, although there is considerable additional variance whereby further research could identify other variables (e.g. biological, neurobiological) to create a more robust predictive index of depression.

Last, these findings linking the onset of depressive symptoms and disability suggest that prompt identification and management of depression may prevent continuous and persistent depressive symptoms and thus improve both psychological and functional outcomes after a disabling medical event. Yet, treating depressive symptoms in this context poses a challenge. Antidepressant medications are not indicated in the absence of a major depression diagnosis and they are often poorly tolerated and ineffective in the very old and medically ill (Álamo et al. 2014; Diniz & Reynolds, 2014; Iaboni et al. 2015). Likewise, psychotherapy would be difficult to carry out with medically ill elders in inpatient and rehabilitation medical settings. We would argue that practical, non-pharmacological interventions are needed that fit the population and setting of medically ill, disabled elderly. Given the strong and likely bidirectional relationship between depression and disability, such strategies might include earlier and more intensive rehabilitation after discharge from the hospital, as well as structured exercise programs to prevent plateauing of function and mobility after formal rehabilitation has ceased. Structured exercise has been shown effective in reducing depression severity in older adults (Bridle et al. 2012) and both intensive, supervised exercise programs and progressive resistance training improve functional recovery after hip fracture (Beaupre et al. 2013). Our group is testing an intervention, ‘Enhanced Medical Rehabilitation’, designed to increase the intensity of post-acute physical and occupational therapy, relying on motivational techniques to overcome patients’ emotional barriers to rehabilitation participation such as depression (Lenze et al. 2013). Further testing of this and other practical interventions could help maximize recovery efforts post-fracture when depressive symptoms arise, providing relief from intertwined depression and disability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the assistance with data management by Peter Dore and data collection by Leah Wendleton. The National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH; R01 MH074596, R34MH101433, and T32 MH014677-36) and Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR000448 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research supported the conception and design of the study, data collection and management, statistical analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002974.

References

- Álamo C, López-Muñoz F, García-García P, García-Ramos S. Risk–benefit analysis of antidepressant drug treatment in the elderly. Psychogeriatrics. 2014;14:261–268. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaupre LA, Binder EF, Cameron ID, Jones CA, Orwig D, Sherrington C, Magaziner J. Maximising functional recovery following hip fracture in frail seniors. Best Practice and Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2013;27:771–788. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, Braam AW, Smit JH, Van Tilburg W. Consequences of major and minor depression in later life: a study of disability, well-being and service utilization. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:1397–1409. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler SE, Liu L, Obrizan M, Cook EA, Wright KB, Geweke JF, Chrischilles EA, Pavlik CE, Wallace RB, Ohsfeldt RL, Jones MP, Rosenthal GE, Wolinsky FD. The aftermath of hip fracture: discharge placement, functional status change, and mortality. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;170:1290–1299. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CZ, Shapiro N, Chambless DL, Ahrens AH. Are emotions frightening? II: an analogue study of fear of emotion, interpersonal conflict, and panic onset1. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36:3–15. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridle C, Spanjers K, Patel S, Atherton NM, Lamb SE. Effect of exercise on depression severity in older people: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;201:180–185. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.095174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Craig TKJ, Harris TO, Herbert J, Hodgson K, Tansey KE, Uher R. Functional polymorphism in the brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene interacts with stressful life events but not childhood maltreatment in the etiology of depression. Depression and Anxiety. 2014;31:326–334. doi: 10.1002/da.22221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleeland C, Ryan R. Annals of the Academy of Medicine. Vol. 23. Singapore: 1994. Pain assessment: global use of the brief pain inventory. pp. 129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denkinger MD, Lukas A, Nikolaus T, Peter R, Franke S, Group for the A study Multisite pain, pain frequency and pain severity are associated with depression in older adults: results from the ActiFE Ulm study. Age and Ageing. 2014;43:510–514. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devanand DP, Kim MK, Paykina N, Sackeim HA. Adverse life events in elderly patients with major depression or dysthymic disorder and in healthy-control subjects. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;10:265–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz BS, Reynolds CF. Major depressive disorder in older adults: benefits and hazards of prolonged treatment. Drugs and Aging. 2014;31:661–669. doi: 10.1007/s40266-014-0196-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein A. Mood and motivation in rehabilitation. In: Stuss DT, Winocur G, Robertson IH, editors. Cognitive Neurorehabilitation. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1999. pp. 230–239. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-CV) American Psychiatric Press Inc.; Washington, DC.: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- George LK, Blazer DG, Hughes DC, Fowler N. Social support and the outcome of major depression. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;154:478–485. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens JL, Sanft TB, Marcantonio ER. Functional recovery after hip fracture: the combined effects of depressive symptoms, cognitive impairment, and delirium. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56:1075–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan EL, Magaziner J, Wang JJ, Eastwood EA, Silberzweig SB, Gilbert M, Morrison RS, McLaughlin MA, Orosz GM, Siu AL. Mortality and locomotion 6 months after hospitalization for hip fracture: risk factors and risk-adjusted hospital outcomes. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285:2736–2742. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann N, Black SE, Lawrence J, Szekely C, Szalai JP. The sunnybrook stroke study a prospective study of depressive symptoms and functional outcome. Stroke. 1998;29:618–624. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.3.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershkovitz A, Kalandariov Z, Hermush V, Weiss R, Brill S. Factors affecting short-term rehabilitation outcomes of disabled elderly patients with proximal hip fracture. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2007;88:916–921. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyes GJ, Tucker A, Marley D, Foster A. Predictors for 1-year mortality following hip fracture: a retrospective review of 465 consecutive patients. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00068-015-0556-2. Published online: 11 August 2015. PMID: 26260068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes JD, House AO. Psychiatric illness in hip fracture. Age and Ageing. 2000a;29:537–546. doi: 10.1093/ageing/29.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes J, House A. Psychiatric illness predicts poor outcome after surgery for hip fracture: a prospective cohort study. Psychological Medicine. 2000b;30:921–929. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iaboni A, Seitz DP, Fischer HD, Diong CC, Rochon PA, Flint AJ. Initiation of antidepressant medication after hip fracture in community-dwelling older adults. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2015;23:1007–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson WC. Assessing and managing pain and major depression with medical comorbidities. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2013;74:e24. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13039vs5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MP, Karoly P. Self-report scales and procedures for assessing pain in adults. In: Turk DC, Melzack R, Turk DC, Melzack R, editors. Handbook of Pain Assessment. Guilford Press; New York, NY, US.: 1992. pp. 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Karp JF, Scott J, Houck P, Reynolds CF, Kupfer DJ, Frank E. Pain predicts longer time to remission during treatment of recurrent depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:591–597. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H. Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1983;140:734–739. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:837–841. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy GJ, Kelman HR, Thomas C. The emergence of depressive symptoms in late life: the importance of declining health and increasing disability. Journal of Community Health. 1990;15:93–104. doi: 10.1007/BF01321314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S-M, Moon Y-W, Lim S-J, Yoon B-K, Min Y-K, Lee D-Y, Park Y-S. Prediction of survival, second fracture, and functional recovery following the first hip fracture surgery in elderly patients. Bone. 2012;50:1343–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.02.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvelde T, McVeigh C, Toson B, Greenaway M, Lord SR, Delbaere K, Close JCT. Depressive symptomatology as a risk factor for falls in older people: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2013;61:694–706. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landerman R, George LK, Campbell RT, Blazer DG. Alternative models of the stress buffering hypothesis. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1989;17:625–642. doi: 10.1007/BF00922639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Host HH, Hildebrand M, Morrow-Howell N, Carpenter B, Freedland KE, Baum CM, Binder EF. Enhanced medical rehabilitation is feasible in a skilled nursing facility: preliminary data on a novel treatment for older adults with depression. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013;21:307. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Munin MC, Dew MA, Rogers JC, Seligman K, Mulsant BH, Reynolds CF. Adverse effects of depression and cognitive impairment on rehabilitation participation and recovery from hip fracture. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004;19:472–478. doi: 10.1002/gps.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Munin MC, Skidmore ER, Amanda Dew M, Rogers JC, Whyte EM, Quear T, Begley A, Reynolds CF. Onset of depression in elderly persons after hip fracture: implications for prevention and early intervention of late-life depression. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55:81–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Rogers JC, Martire LM, Mulsant BH, Rollman BL, Dew MA, Schulz R, Reynolds CF III. The association of late-life depression and anxiety with physical disability: a review of the literature and prospectus for future research. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;9:113–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaziner J, Fredman L, Hawkes W, Hebel JR, Zimmerman S, Orwig DL, Wehren L. Changes in functional status attributable to hip fracture: a comparison of hip fracture patients to community-dwelling aged. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157:1023–1031. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MD, Paradis CF, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Stack JA, Rifai AH, Mulsant B, Reynolds CF III. Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the cumulative illness rating scale. Psychiatry Research. 1992;41:237–248. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90005-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morghen S, Bellelli G, Manuele S, Guerini F, Frisoni GB, Trabucchi M. Moderate to severe depressive symptoms and rehabilitation outcome in older adults with hip fracture. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2011;26:1136–1143. doi: 10.1002/gps.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morone NE, Weiner DK, Belnap BH, Hum B, Karp JF, Mazumdar S, Houck PR, He F, Rollman BL. The impact of pain and depression on post-CABG recovery. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2010;72:620–625. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181e6df90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossey JM, Knott K, Craik R. The effects of persistent depressive symptoms on hip fracture recovery. Journal of Gerontology. 1990;45:M163–M168. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.5.m163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Thomsen T, Mittermeier O, Ganzer S. Unrecognised and untreated depression in geriatric patients with hip fractures. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;17:683–684. doi: 10.1002/gps.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS, Odgers CL. Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:109–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J, Rijsdijk FV, Sullivan M, van Sonderen E, Kempen GIJM. Temporal and reciprocal relationship between iadl/adl disability and depressive symptoms in late life. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57:P338–P347. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.4.p338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oude Voshaar RC, Banerjee S, Horan M, Baldwin R, Pendleton N, Proctor R, Tarrier N, Woodward Y, Burns A. Predictors of incident depression after hip fracture surgery. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15:807–814. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318098610c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkkari J, Kannus P, Palvanen M, Natri A, Vainio J, Aho H, Vuori I, Järvinen M. Majority of hip fractures occur as a result of a fall and impact on the greater trochanter of the femur: a prospective controlled hip fracture study with 206 consecutive patients. Calcified Tissue International. 1999;65:183–187. doi: 10.1007/s002239900679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BW, Leveille S, Ferrucci L, van Eijk JT, Guralnik JM. Exploring the effect of depression on physical disability: longitudinal evidence from the established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1346–1352. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic NM, Milovanovic DR, Ignjatovic Ristic D, Riznic N, Ristic B, Stepanovic Z. Factors associated with severe postoperative pain in patients with total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthopaedica et Traumatologica Turcica. 2014;48:615–622. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2014.14.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed ‘up & go’: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1991;39:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince MJ, Harwood RH, Blizard RA, Thomas A, Mann AH. Impairment, disability and handicap as risk factors for depression in old age: the Gospel Oak project V. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:311–321. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson KS, Dixon D, Nowotny P, Ricci WM, Binder EF, Rodebaugh TL, Wendleton L, Doré P, Lenze EJ. Association of functional polymorphisms from brain-derived neurotrophic factor and serotonin-related genes with depressive symptoms after a medical stressor in older adults. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0120685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salpakoski A, Törmäkangas T, Edgren J, Sihvonen S, Pekkonen M, Heinonen A, Pesola M, Kallinen M, Rantanen T, Sipilä S. Walking recovery after a hip fracture: a prospective follow-up study among community-dwelling over 60-year old men and women. BioMed Research International. 2014;2014:289549. doi: 10.1155/2014/289549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyu Y-IL, Cheng H-S, Teng H-C, Chen M-C, Wu C-C, Tsai W-C. Older people with hip fracture: depression in the postoperative first year. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009;65:2514–2522. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs B, Stubbs J, Gnanaraj SD, Soundy A. Falls in older adults with major depressive disorder (MDD): a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis of prospective studies. International Psychogeriatrics. 2016;28:23–29. doi: 10.1017/S104161021500126X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Terracciano A, Milaneschi Y, An Y, Ferrucci L, Zonderman AB. The trajectory of depressive symptoms across the adult life span. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:803–811. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swardfager W, Herrmann N, Marzolini S, Saleem M, Farber SB, Kiss A, Oh PI, Lanctôt KL. Major depressive disorder predicts completion, adherence, and outcomes in cardiac rehabilitation: a prospective cohort study of 195 patients with coronary artery disease. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2011;72:1181–1188. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05810blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz JR, Williamson DE, Hariri AR. Developmental change in amygdala reactivity during adolescence: effects of family history of depression and stressful life events. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;172:276–283. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14020195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trzepacz PT, Dew MA. Further analyses of the delirium rating scale. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1995;17:75–79. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(94)00095-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng M-Y, Shyu Y-IL, Liang J. Functional recovery of older hip-fracture patients after interdisciplinary intervention follows three distinct trajectories. Gerontologist. 2012;52:833–842. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CS, Tinetti ME, Kasl SV, Peduzzi PN. The role of pain in the recovery of instrumental and social functioning after hip fracture. Journal of Aging and Health. 2006;18:743–762. doi: 10.1177/0898264306293268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson GM, Schulz R. Pain, activity restriction, and symptoms of depression among community-residing elderly adults. Journal of Gerontology. 1992;47:P367–P372. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.6.p367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiss AM, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Relationship of physical disease and functional impairment to depression in older people. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11:572–581. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.4.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman J, Koval K, Aharonoff G, Hiebert R, Skovron M. A functional recovery score for elderly hip fracture patients: I. development. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma January. 2000;14:20–25. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200001000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman JD. Hip fracture. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;334:1519–1525. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606063342307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.