Abstract

Purpose

Anxiety may serve as a major barrier to participation in AS. Intolerance of uncertainty—the tendency to perceive the potential for negative events as threatening—has been linked to cancer-related worry. Accordingly, we explored prospectively the relationship of intolerance of uncertainty with anxiety along with other clinical factors among men managed with AS for prostate cancer.

Materials and Methods

From 2011–2014, 119 men with D’Amico low-risk prostate cancer participating in active surveillance completed the HADS, MAX-PC, IUS, and IPSS surveys. We evaluated the relationship between anxiety and IUS score after adjusting for patient characteristics, cancer information, and IPSS score using bivariable and multivariable analyses.

Results

A number of men reported clinically significant anxiety on the generalized (n=18, 15.1%) and prostate-cancer-specific (n=17, 14.3%) scales. In bivariable analyses, men with moderate/severe urinary symptoms and higher IUS scores reported more generalized and prostate-cancer-specific anxiety than men with mild urinary symptoms and lower IUS scores, respectively (p≤0.008). Men with depressive symptoms (p=0.024) or family history of prostate cancer (p=0.006) experienced greater generalized anxiety. In multivariable analysis, IUS score was significantly associated with generalized (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.09–1.38) and prostate-cancerspecific anxiety (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.13–1.49) while moderate/severe urinary symptoms were associated with prostate-cancer-specific anxiety (OR 6.89, 95% CI 1.33–35.68).

Conclusions

Intolerance of uncertainty and urinary symptoms may promote anxiety among men on AS for prostate cancer. Patient education, management of lower urinary tract symptoms, and behavioral interventions may lessen anxiety related to uncertainty intolerance and help maintain patient engagement in AS.

Keywords: active surveillance, anxiety, prostate neoplasm, uncertainty

Introduction

Most men with prostate cancer are currently diagnosed with localized, low-risk disease unlikely to be lethal.1, 2 Nevertheless, 70–80% of these men undergo surgery or radiation, which carry potential short-term and longstanding side effects.3, 4 As an alternative, AS offers acceptable cancer-specific survival and minimal morbidity.5, 6 Accordingly, AS is now considered a valid management strategy with usage reaching as many as half of men with lowrisk prostate cancer in certain regions of the United States.4, 7, 8

Despite its potential benefits, AS has been underutilized for men with localized prostate cancer.4 One often-mentioned reason is the toll of cancer-related anxiety on expectantly managed patients.9 Because the underlying threat from prostate cancer among surveillance patients is small but ever-present,5 the severity of distress may vary with perceptions of health and overall psychological adjustment.10 Intolerance of uncertainty—a predisposing trait for anxiety marked by the tendency to perceive uncertainty as threatening11—perpetuates anxiety symptoms in patients with a variety of health conditions including prostate cancer.12, 13 Men on AS may be particularly vulnerable given the monitoring-based approach to care. Interval PSA testing and prostate biopsies integral to AS could exacerbate perceptions of threat and therefore worry. Physical symptoms and other patient attributes may also interact with uncertainty intolerance.14 However, to date, the impact of intolerance of uncertainty among men undergoing AS of prostate cancer is unexplored.

In this context, we hypothesized that men on AS for prostate cancer with greater intolerance of uncertainty would be more likely to experience anxiety and examined this using a prospective cohort study. In understanding this cognitive underpinning, we may facilitate the development of strategies that reduce the psychological burden of expectant management approaches for men with prostate cancer.

Material and Methods

Patient Cohort

From February 2011–June 2014, we enrolled 267 men into the University of California, Los Angeles AS program, an institutional review board-approved longitudinal registry with entry restricted to men with low- or intermediate-risk prostate cancer based on the D ׳Amico risk classification.15 As part of this prospective cohort study, 257 (96.3%) men completed questionnaires related to anxiety, depression, quality of life, and urinary symptoms upon entry. Because the impact of prostate cancer on patient-reported mental health tends to lessen over time,16 we reduced the study population to men enrolled within a year of initial diagnosis (N=144). Finally, to limit heterogeneity, we focused specifically on men with low-risk disease (i.e, ≤clinical T2, Gleason 6, PSA 10 ng/ml), resulting in a final cohort of 119 men.

As part of the study protocol, participants underwent a confirmatory MRI-fusion guided biopsy, PSA/physical exam every 6 months, and repeat biopsy within 1 year then annually or biannually thereafter. Participants completed surveys upon study entry and during subsequent follow-ups, either in clinic or via a web-based electronic platform. Initially, participants completed questionnaires in 6-month intervals. To reduce patient burden, the protocol was amended to lengthen the interval to every 12 months midway through the study. At the time of this analysis, 69 of the 119 entrants (58.0%) completed two or more surveys, yielding a subcohort of men with short-term follow-up data.

Primary outcomes

Two validated, patient-reported instruments were used to assess anxiety: 1) the HADS anxiety subscale for generalized anxiety; and 2) the MAX-PC for prostate-cancer-specific anxiety. For each scale, we used established cutoffs (i.e., ≥8 for HADS and ≥26 for MAX-PC) to create binary measures of anxiety.17, 18

Intolerance of uncertainty and additional covariates

To measure intolerance of uncertainty, we used a modified version of the IUS. We pared the original 27-item instrument to 8 items based on the highest item-total correlations from the initial validation study.19 Additionally, we collected information pertaining to patient demographics, comorbidities, family history, clinic visits, and indicators of cancer severity by patient-report and through medical chart review. We assessed depressive symptoms with the depression subscale of the HADS instrument and urinary symptoms with the IPSS.

Statistical Analysis

First, we examined the relationships at study entry between generalized and prostate-cancer-specific anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty as well as relevant demographic and clinical variables using Student’s t-test or chi-squared test as appropriate. Next, we performed multivariable logistic regression to assess the association between intolerance of uncertainty scores and anxiety at study entry, adjusting for patient age, race, marital status, education, comorbidities, urinary symptom score, family history of prostate cancer, and depressive symptoms. From this, we calculated the model-adjusted probability of anxiety at the mean intolerance of uncertainty level and half standard deviations above and below, which represent clinically significant changes in score.20 We also compared the adjusted probability of anxiety according to mild versus moderate/severe urinary symptoms using an IPSS cutoff of 7.

As an exploratory analysis, we examined the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and anxiety over the early surveillance period. First, we compared baseline characteristics between men yet to return for follow-up versus those completing at least 2 surveys using Student’s t-test or chi-squared test as appropriate. Next, for the sub-cohort with follow-up, we stratified survey responses into four time-based categories (i.e., baseline, <9 months, 9–15 months, and >15 months) and examined the relationship over time using chi-squared tests and ANOVA. Finally, we constructed repeated-measures, multivariable logistic regression models using all available data from study entry to last follow-up. We refitted our multivariable models and included time since study entry as an additional covariate, and then again determined the model-adjusted probability of anxiety, both generalized and prostate-cancer-specific. As sensitivity analyses, we also examined models that included men with intermediate-risk disease with further adjustment for PSA and Gleason score and incorporated selected interaction terms between IUS score and other clinical variables.

All statistical testing was 2-sided, completed using computerized software (SAS version 9.4; Cary, NC), and carried out at the 5% significance level. The registry and this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Results

Baseline analysis

Among 119 men, 18 (15.1%) and 17 (14.3%) reported generalized and/or prostate-cancer-specific anxiety, respectively. Table 1 presents several factors that were associated significantly with anxiety. Intolerance of uncertainty related directly to generalized and prostate-cancer-specific anxiety (p≤0.001). Additionally, men with elevated depressive symptoms (p=0.024), moderate/severe urinary symptoms (p=0.008), or a family history of prostate cancer (p=0.006) were more likely to have generalized anxiety, whereas men with moderate/severe urinary symptoms were more like to have anxiety related to prostate cancer (p=0.003). We did not observe an association between PSA and generalized anxiety (p=0.438), prostate-cancer-specific anxiety (p=0.760), or PSA-specific anxiety as measured by the PSA subscale of the MAX-PC instrument (p=0.916). We found no difference in the number of previous biopsies (p=0.251) or the performance of biopsy at the time of survey administration (p=0.433) between patients with and without anxiety. As of June 2014, 5 (5.0%) men without generalized anxiety and 1 (5.6%) with generalized anxiety opted to withdraw from AS without evidence of disease progression (p=0.918). Seven men proceeded to treatment due to disease progression.

Table 1.

Patient and clinical factors according to generalized and prostate-cancer-specific anxiety

| Generalized Anxiety1 (N=18) |

No Anxiety1 (N=101) |

P-value | Prostate Cancer Anxiety2 (N=17) |

No Prostate Cancer Anxiety2 (N=102) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), SD | 62.5 (6.0) | 63.8 (7.5) | 0.503 | 62.8 (5.9) | 63.7 (7.5) | 0.636 |

| Non-white race/ethnicity | 16.7% | 14.9% | 0.735 | 11.8% | 15.7% | 0.999 |

| Married | 83.3% | 81.2% | 1.000 | 76.5% | 82.4% | 0.517 |

| College graduate | 61.1% | 77.0% | 0.237 | 70.6% | 75.2% | 0.765 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), SD | 26.9 (3.5) | 26.6 (3.9) | 0.760 | 26.3 (3.4) | 26.7 (3.9) | 0.760 |

| Baseline PSA (ng/ml), SD | 3.9 (2.2) | 4.4 (2.5) | 0.438 | 4.5 (2.5) | 4.3 (2.4) | 0.701 |

| Biopsy at time of survey | 44.4% | 54.5% | 0.433 | 47.1% | 53.9% | 0.600 |

| Any comorbidity | 44.4% | 41.6% | 0.821 | 29.4% | 44.1% | 0.255 |

| BPH | 33.3% | 32.7% | 0.956 | 41.2% | 31.4% | 0.425 |

| Family history of prostate cancer | 55.6% | 20.8% | 0.006 | 47.1% | 22.5% | 0.069 |

| Depression3 | 16.7% | 2.0% | 0.024 | 11.8% | 2.9% | 0.148 |

| IPSS Score | ||||||

| - 0–7 | 27.8% | 61.4% | 0.008 | 23.5% | 61.8% | 0.003 |

| - 8+ | 72.2% | 38.3% | 76.5% | 38.2% | ||

| IPSS Bother | ||||||

| - 0–2 | 61.1% | 81.2% | 0.069 | 58.8% | 81.4% | 0.055 |

| - 3–6 | 38.9% | 18.8% | 41.2% | 18.6% | ||

| IUS total score, SD | 17.2 (6.5) | 10.9 (4.2) | <0.001 | 18.2 (7.9) | 10.8 (3.6) | |

Based on the Anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale using a cutoff of 8.

Based on the Memorial Anxiety Scale for Prostate Cancer using a cutoff of 26.

Based on the Depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale using a cutoff of 8.

Abbreviations: SD – standard deviation; PSA – Prostatic Specific Antigen; BPH – Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia; HADS – Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IPSS – International Prostate Symptom Score; IUS – Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale

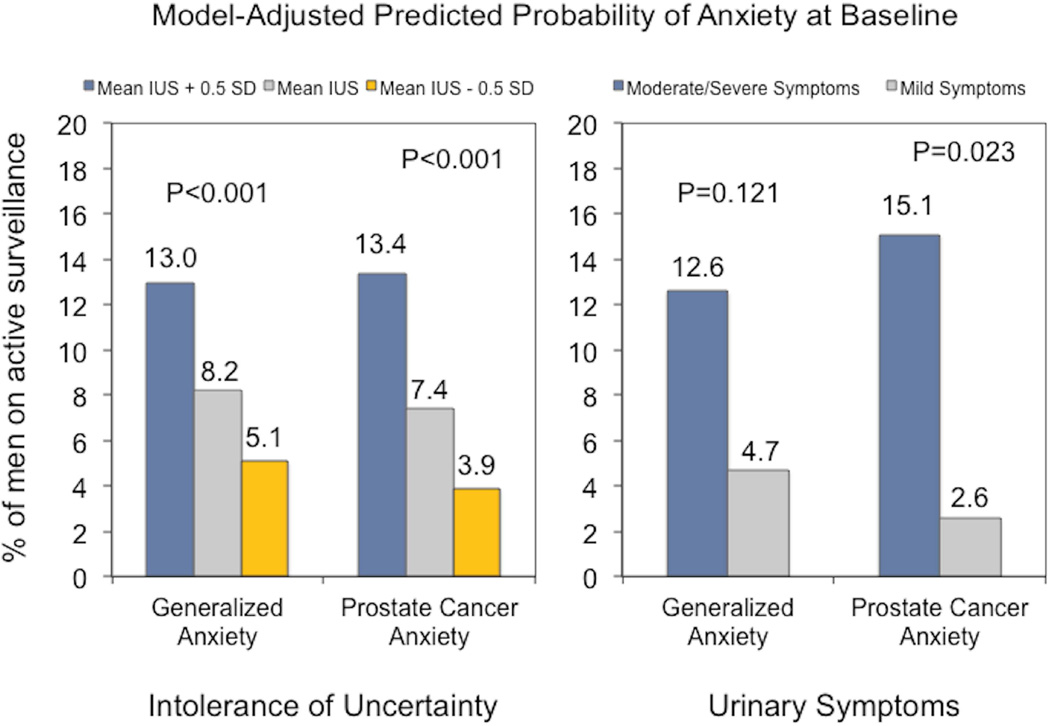

In the multivariable analyses (supplemental Table 1), intolerance of uncertainty remained significantly associated with generalized anxiety (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.09–1.38) and prostate-cancer- specific anxiety (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.13–1.49). Though not significantly associated with generalized anxiety (OR 2.88, 95% CI 0.76–10.99), moderate/severe urinary symptoms were more common among men with prostate-cancer-specific anxiety (OR 6.89, 95% CI 1.33–35.68). Men with a family history of prostate cancer also had an increased likelihood of generalized anxiety (OR 4.26, 95% 1.11–16.42). Figure 1 illustrates the change in probability of generalized and prostate-cancer-specific anxiety in response to meaningful changes in intolerance of uncertainty and for men with moderate/severe versus mild urinary symptoms.

Figure 1.

Probability of generalized and prostate-cancer-specific anxiety at baseline according to intolerance of uncertainty score and urinary symptoms. Probabilities and p-values are derived from the multivariable regression models and reported for the mean IUS score ± a half-standard deviation and urinary symptoms dichotomized into mild versus moderate/severe symptoms based on the IPSS.

Longitudinal Analysis

Sixty-nine men completed 2 or more surveys with a median follow-up of 12 months (interquartile range 7–18 months). Patient demographics, cancer-specific covariates, and the proportion with anxiety did not differ significantly between the 69 patients with follow-up data and the 50 with only baseline data (p>0.05). Patient-reported outcomes did not vary significantly with time (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient-reported urinary symptoms and psychosocial measures over time

| Measure | Baseline (N=69) | Time Period 1 (N=40) | Time Period 2 (N=43) | Time Period 3 (N=40) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate/severe IPSS1 | 43.5% | 55.0% | 51.2% | 55.0% | 0.573 |

| IUS Score (SD) | 12.0 (5.8) | 12.5 (6.3) | 12.3 (6.7) | 13.4 (7.0) | 0.723 |

| Generalized anxiety2 | 15.9% | 20.0% | 11.9% | 12.5% | 0.595 |

| Prostate cancer anxiety3 | 14.5% | 15.0% | 14.6% | 12.5% | 0.988 |

Based on the International Prostate Symptom Score using a cutoff of 8.

Based on the Anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale using a cutoff of 8.

Based on the Memorial Anxiety Scale for Prostate Cancer using a cutoff of 26.

Abbreviations: IPSS – International Prostate Symptom Score; IUS – intolerance of uncertainty scale; SD – standard deviation.

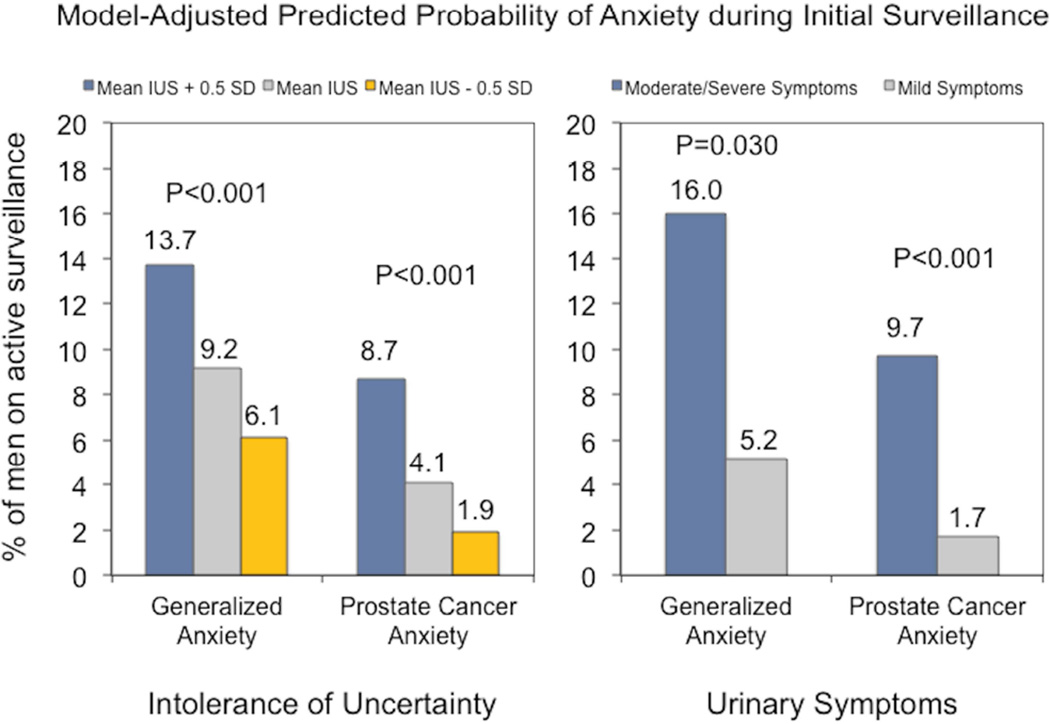

Over the initial surveillance period, greater intolerance of uncertainty (OR 1.15, 95% CI 1.07–1.23) and moderate/severe urinary symptoms (OR 3.44, 95% CI 1.13–10.50) were associated with greater odds of generalized anxiety compared to lower intolerance of uncertainty and mild urinary symptoms, respectively, in the repeated-measures, multivariable regression models (supplemental Table 1). We noted similar findings with respect to prostate-cancer-specific anxiety (intolerance of uncertainty: OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.17–1.40; moderate/severe urinary symptoms: OR 6.18, 95% CI 2.36–16.20). Predicted probabilities are depicted in Figure 2. Months in surveillance did not predict generalized (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.89–1.01) or prostate-cancer-specific anxiety (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.85–1.01). Otherwise, only non-white race/ethnicity was associated with prostate-cancer-specific anxiety (OR 3.82, 95% CI 1.05–13.82). Study findings remained consistent across the specified sensitivity analyses (supplement Table 2).

Figure 2.

Probability of generalized and prostate-cancer-specific anxiety over the initial surveillance period according to intolerance of uncertainty and urinary symptoms. Probabilities and p-values are derived from the repeated-measures multivariable models and are reported for the mean IUS score ± a half-standard deviation and urinary symptoms dichotomized into mild versus moderate/severe symptoms based on the IPSS.

Discussion

Given the indolent nature of low-risk prostate cancer and the probability of death from other causes, AS has been endorsed as a management strategy by several organizations including the American Urological Association.2, 7 While utilization trends indicate increasing use of AS,4, 8 many men continue to opt for surgery or radiation despite the small margin for benefit.2 Among a host of considerations, mental and emotional health have been found to vary with treatment and likely factor into a man’s treatment decision.16

Within this health domain, anxiety and management of uncertainty arise as potential barriers to the adoption of and adherence to AS by patients and providers.9, 21 Consistent with previous studies,22 approximately 1 in 5 men engaged in our surveillance protocol reported clinically significant anxiety. Additionally, the proportion of men experiencing anxiety did not decline, at least over the short-term. Though not assessed here, registry data have suggested similar or higher levels of anxiety among men treated with AS compared with men treated with radical prostatectomy.16, 23 In total, these findings confirm that pervasive worry and psychological distress occur with some regularity within the expectantly managed population.

Anxiety during AS appears to be linked to both psychological and clinical factors that may be modifiable. For men with prostate cancer, uncertainty concerns appear crucial and often stem from questions about risk of mortality, disease progression and migration, treatment outcomes, and/or treatment-related side effects.21 Although uncertainty itself can be distressing, a patient’s attitude toward uncertainty may be particularly important. The tendency to consider uncertainty threatening, unacceptable, or unmanageable may be a principal precursor to pervasive worry and anxiety. As explored in this study, the probability of anxiety increased substantially with meaningful increases in intolerance of uncertainty. Similar findings have been reported for patients with lung cancer as well as men treated for prostate cancer.13, 24

In addition to intolerance of uncertainty, urinary symptoms also had a significant relationship with anxiety. Interestingly, the interpretation of bodily cues has been linked to patient-reported psychological stress throughout the spectrum of prostate cancer care. Urinary symptoms, in particular, have been associated with heightened levels of cancer fear and mood disturbances in men treated with radical prostatectomy.25 Previous research also suggests that uncertainty intolerance perpetuates misinterpretation of bodily sensations during an anxiety or panic episode among patients with anxiety disorders.14 Consistent with the Common-Sense Model of Illness Representations,26 somatic signals—especially when arising from the urinary system—might facilitate catastrophic thinking and cycles of worry in men with high intolerance of uncertainty. Taken together, intolerance of uncertainty, urinary symptoms, and their interplay may serve as a potent catalyst for anxiety among men pursuing AS.

Our findings should be considered in the context of several limitations. First, because this prospective cohort study focuses on AS participants, we are unable to ascertain whether a relationship also exists between intolerance of uncertainty and the initial treatment decision. Similarly, we cannot assess whether the influence of uncertainty intolerance on anxiety varies with the selected management modality. Future empirical work is needed to understand the role of intolerance of uncertainty on decision-making and management-specific anxiety, particularly for men selecting definitive treatment despite being suitable candidates for AS. Second, our study may miss subtle changes in anxiety associated with surveillance-related testing. It is worth noting, however, that patient-reported anxiety did not differ according to receipt of biopsy or PSA level. Third, because of the limited cohort size and follow-up, we are unable to assess whether intolerance of uncertainty and urinary symptoms affect anxiety and discontinuation of AS over the long-term and if this changes substantively over time. As part of this cohort study, a planned future analysis with more mature longitudinal data may clarify the time-varying interplay among determinants of anxiety, biochemical and/or pathologic changes, and surveillance attrition, providing additional information that may aid patient selection and inter-surveillance management. Similarly, additional determinants of anxiety may become identifiable as the study population grows. Fourth, given our study design, we are unable to demonstrate causality, especially as it relates to the observed relationship between urinary symptoms and anxiety. Of note, treatment of intolerance of uncertainty reduces anxiety symptoms, supporting the concept of intolerance of uncertainty as a cause of anxiety.27 Finally, as our study describes findings from a single institution, they may not be broadly generalizable. For example, illness-related uncertainty, which was not measured in the present study, has been shown to differ based on patient race/ethnicity and education level. Intolerance of uncertainty and its relationship with anxiety may also vary across practice settings depending on the patient-mix.28

These limitations notwithstanding, our findings have potential implications for professionals caring for men with prostate cancer on AS given the modifiable nature of intolerance of uncertainty and urinary symptoms. In the case of the former, cognitive-behavioral therapy that helps patients manage or accept uncertainty has been shown to reduce anxiety in a randomized control trial.27 Previous qualitative work also suggests that men on AS employ several coping mechanisms to deal with uncertainty such as framing prostate cancer as a benign process or augmenting surveillance with adjuncts (e.g., dietary modification, exercise).21 While future research will be pivotal, cognitive and self-management interventions tailored toward these coping mechanisms, along with effective patient education, may help reduce uncertainty-related distress.29 Multidisciplinary prostate cancer survivorship programs that include social workers, psychologists, and psychiatrists may be well positioned to offer such services to at-risk men.

Urologic management of urinary symptoms may further help lower anxiety for men on AS. Some data suggest that reducing lower urinary tract symptoms—either medically or surgically—may lessen anxiety among men with benign prostatic hypertrophy.30 Though additional studies are needed, treatment of urinary symptoms may provide similar relief to men on AS with the added potential benefit of removing body cues that trigger and amplify intolerance of uncertainty. In identifying and addressing these determinants, anxiety may be minimized during AS, making this management approach more acceptable to men with low-risk prostate cancer.

Conclusions

Intolerance of uncertainty may function as a potent determinant of anxiety among men pursuing AS for low-risk prostate cancer. Lower urinary tract symptoms also are associated with patient-reported anxiety. Risk assessment, patient education, management of lower urinary tract symptoms, and behavioral interventions to increase uncertainty tolerance may lessen anxiety and help maintain patient engagement in AS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Award Number R01CA158627 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. Additional support was provided by UCLA Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute Grant No. UL1TR000124, the Beckman Coulter Foundation, the Jean Perkins Foundation, and the Steven C. Gordon Family Foundation. Investigator support provided by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations through the VA/Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program (HT); The American Cancer Society (HT, CPF); and The Urology Care Foundation (CPF).

Key of Definitions for Abbreviations

- AS

Active Surveillance

- HADS

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- MAX-PC

Memorial Anxiety Scale for Prostate Cancer

- IUS

Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale

- IPSS

International Prostate Symptom Score

- PSA

Prostate-Specific Antigen

- OR

Odds Ratio

- CI

Confidence Interval

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hankey BF, Feuer EJ, Clegg LX, et al. Cancer surveillance series: interpreting trends in prostate cancer--part I: Evidence of the effects of screening in recent prostate cancer incidence, mortality, and survival rates. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1017–1024. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.12.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daskivich TJ, Lai J, Dick AW, et al. Comparative effectiveness of aggressive versus nonaggressive treatment among men with early-stage prostate cancer and differing comorbid disease burdens at diagnosis. Cancer. 2014;120:2432–2439. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Resnick MJ, Koyama T, Fan KH, et al. Long-term functional outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:436–445. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiner AB, Patel SG, Etzioni R, Eggener SE. National trends in the management of low and intermediate risk prostate cancer in the United States. J Urol. 2015;193:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.07.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klotz L, Vesprini D, Sethukavalan P, et al. Long-term follow-up of a large active surveillance cohort of patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:272–277. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tosoian JJ, Trock BJ, Landis P, et al. Active surveillance program for prostate cancer: an update of the Johns Hopkins experience. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2185–2190. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.8112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson I, Thrasher JB, Aus G, et al. Guideline for the management of clinically localized prostate cancer: 007 update. J Urol. 2007;177:2106–2131. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Womble PR, Montie JE, Ye Z, et al. Contemporary use of initial active surveillance among men in Michigan with low-risk prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;67:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kazer MW, Psutka SP, Latini DM, Bailey DE., Jr Psychosocial aspects of active surveillance. Curr Opin Urol. 2013;23:273–277. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32835eff24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, DeLongis A, Gruen RJ. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;50:992–1003. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.5.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen NO, Knauper B, Sammut J. Do individual differences in intolerance of uncertainty affect health monitoring? Psychology & Health. 2007;22:413–430. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buhr K, Dugas MJ. The role of fear of anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty in worry: an experimental manipulation. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenberg SA, Kurita K, Taylor-Ford M, Agus DB, Gross ME, Meyerowitz BE. Intolerance of uncertainty, cognitive complaints, and cancer-related distress in prostate cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2015;24:228–235. doi: 10.1002/pon.3590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carleton RN, Duranceau S, Freeston MH, Boelen PA, McCabe RE, Antony MM. "But it might be a heart attack": intolerance of uncertainty and panic disorder symptoms. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28:463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280:969–974. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Litwin MS, Lubeck DP, Spitalny GM, Henning JM, Carroll PR. Mental health in men treated for early stage prostate carcinoma: a posttreatment, longitudinal quality of life analysis from the Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor. Cancer. 2002;95:54–60. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roth A, Nelson CJ, Rosenfeld B, et al. Assessing anxiety in men with prostate cancer: further data on the reliability and validity of the Memorial Anxiety Scale for Prostate Cancer (MAX-PC) Psychosomatics. 2006;47:340–347. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.4.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buhr K, Dugas MJ. The Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale: psychometric properties of the English version. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40:931–945. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41:582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliffe JL, Davison BJ, Pickles T, Mroz L. The self-management of uncertainty among men undertaking active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer. Qual Health Res. 2009;19:432–443. doi: 10.1177/1049732309332692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van den Bergh RC, Essink-Bot ML, Roobol MJ, et al. Anxiety and distress during active surveillance for early prostate cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:3868–3878. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Punnen S, Cowan JE, Dunn LB, Shumay DM, Carroll PR, Cooperberg MR. A longitudinal study of anxiety, depression and distress as predictors of sexual and urinary quality of life in men with prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2013;112:E67–E75. doi: 10.1111/bju.12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurita K, Garon EB, Stanton AL, Meyerowitz BE. Uncertainty and psychological adjustment in patients with lung cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1396–1401. doi: 10.1002/pon.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ullrich PM, Carson MR, Lutgendorf SK, Williams RD. Cancer fear and mood disturbance after radical prostatectomy: consequences of biochemical evidence of recurrence. J Urol. 2003;169:1449–1452. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000053243.87457.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leventhal H, Brissette I, Leventhal EA. The common-sense model of self-regulation of health and illness. The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour. 2003;1:42–65. [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Heiden C, Muris P, van der Molen HT. Randomized controlled trial on the effectiveness of metacognitive therapy and intolerance-of-uncertainty therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kazer MW, Bailey DE, Jr, Chipman J, et al. Uncertainty and perception of danger among patients undergoing treatment for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2013;111:E84–E91. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11439.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bailey DE, Mishel MH, Belyea M, Stewart JL, Mohler J. Uncertainty intervention for watchful waiting in prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27:339–346. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200409000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quek KF, Razack AH, Chua CB, Low WY, Loh CS. Effect of treating lower urinary tract symptoms on anxiety, depression and psychiatric morbidity: a one-year study. Int J Urol. 2004;11:848–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2004.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.