Abstract

Increasing obesity rates are still a public health priority. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of tailored text messages on body weight change in overweight and obese adults in a community-based weight management program. A secondary aim was to detect behavioral changes in the same population. The study design was quasi-experimental with pretest and posttest analysis, conducted over 12 weeks. A total of 28 participants were included in the analysis. Body weight, eating behaviors, exercise and nutrition self-efficacy, attitude toward mobile technology, social support, and physical activity were assessed at baseline and at 12 weeks. Text messages were sent biweekly to the intervention but not to the control group. At 12 weeks, the intervention group had lost significant weight as compared with the control group. There was a trend toward an improvement in eating behaviors, exercise, and nutrition self-efficacy in the intervention group, with no significant difference between groups. A total of 79% of participants stated that text messages helped in adopting healthy behaviors. Tailored text messages appear to enhance weight loss in a weight management program at a community setting. Large-scale and long-term intervention studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Keywords: Adult, Obesity, Overweight, SMS text messaging, Weight loss

BACKGROUND

Despite multidisciplinary initiatives to reverse ascending rates, the prevalence of overweight and obesity is still on the rise, causing staggering related medical spending.1 Numerous health comorbidities are associated with obesity, including type II diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer.2 The latest estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey obtained in 2009–2010 revealed that 68% of adults in the US are either overweight or obese, making the quest for effective interventions to curb the obesity epidemic a public health priority.3 Lifestyle interventions including physical activity, diet modifications, behavior therapy, and counseling appear to be the most successful interventions for short- and long-term weight management and result in a greater weight loss as compared with interventions including diet and exercise alone.4–7 Behavioral components such as self-monitoring, goal setting, problem solving, social support, and adherence to weight loss programs have shown to be strong predictors of success in weight management.7–11 Lifestyle interventions, however, are often limited by high costs, a decline in adherence to the intervention over time, location, and time constraints to researchers and participants, thus limiting accessibility to the general population.12,13

The ubiquitous spread of mobile phone short message system (SMS) appears to offer an effective alternative to face-to-face approach when delivering behavioral weight management interventions.14 Short message system has the advantage of instantly reaching individuals and is accessed at one’s own convenience and comfort, at a low cost when compared with other media such as telephone calls.15 Researchers have tested the use of SMS across different preventive health behavior interventions and suggested that SMS can be an efficient medium to provide patient education, appointment reminders, behavioral interventions, data acquisition, and two-way communications between individuals and healthcare providers.15–17 In addition, tailored SMSs have been shown to address individual needs and promote the adoption of healthy behaviors in adults, through feedback, intervention initiation, and interactivity between health providers and individuals.18,19

Despite encouraging results, little research has explored the use of SMS in adult weight management.20–23 In most studies, SMS was used with other behavioral components, making it difficult to evaluate its true effect. Thus, the purpose of this study was to address the use of SMS as a stand-alone intervention when administered in the context of a weight loss behavioral program. The primary aim of this study was to assess the effects of tailored SMS on change in body weight. The secondary aim was to assess changes in behavioral outcomes in an experimental versus a control group of overweight and obese adults participating in a structured community weight management program, since group interventions have been found to be superior to individual interventions in helping individuals reach their weight goals.24,25 We hypothesized that tailored SMS would enhance weight loss in the intervention group, facilitate the adoption of healthy eating behaviors, and increase time spent in physical activity per week. In addition, it will improve exercise and nutrition self-efficacy, attitude toward technology, and social support. We anticipated that this study would help shed the light on the usefulness of SMS among participants and identify areas of intervention that need improvement.

To synchronize the different concepts and variables applicable to promoting behavioral change in overweight and obese population, the revised Health Promotion Model served as a conceptual framework to guide the study.26 The model proposes that individuals should develop lifestyles and patterns of behavior to enhance their health and focuses on the following components: individual characteristics and experiences, behavior-specific cognitions and affect and behavior, and health outcomes.

METHODS

Design, Sample, and Settings

A pilot quasi-experimental study was conducted over 12 weeks and was approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Review Board. Participants consented and were recruited from a “Weight Watchers (WW) at work” weight management program. Weight Watchers was found to be the only commercial program with a proven efficacy through a multisite randomized controlled trial, to produce a 5% weight loss of initial body weight at 1 year and maintain a weight loss of 3.2% at 2 years.27,28 Participants were assigned to an intervention or control group based on their WW meeting location in an effort to conserve group cohesiveness. Assessment was conducted at baseline and at 12 weeks. The primary health outcome was change in body weight. Secondary behavior outcomes included eating behaviors, exercise and nutrition self-efficacy, physical activity, social support, attitude toward technology, and adherence to the intervention.

The researcher verbally introduced the intervention, and interested participants were provided written informed consent to read, sign, and return prior to participation. Participants either completed the questionnaires on site or returned them on the following meeting. All participants received monetary compensation ($10.00) upon completion of baseline questionnaires and were entered into a drawing to win one session with a personal trainer upon completion of the postintervention questionnaire.

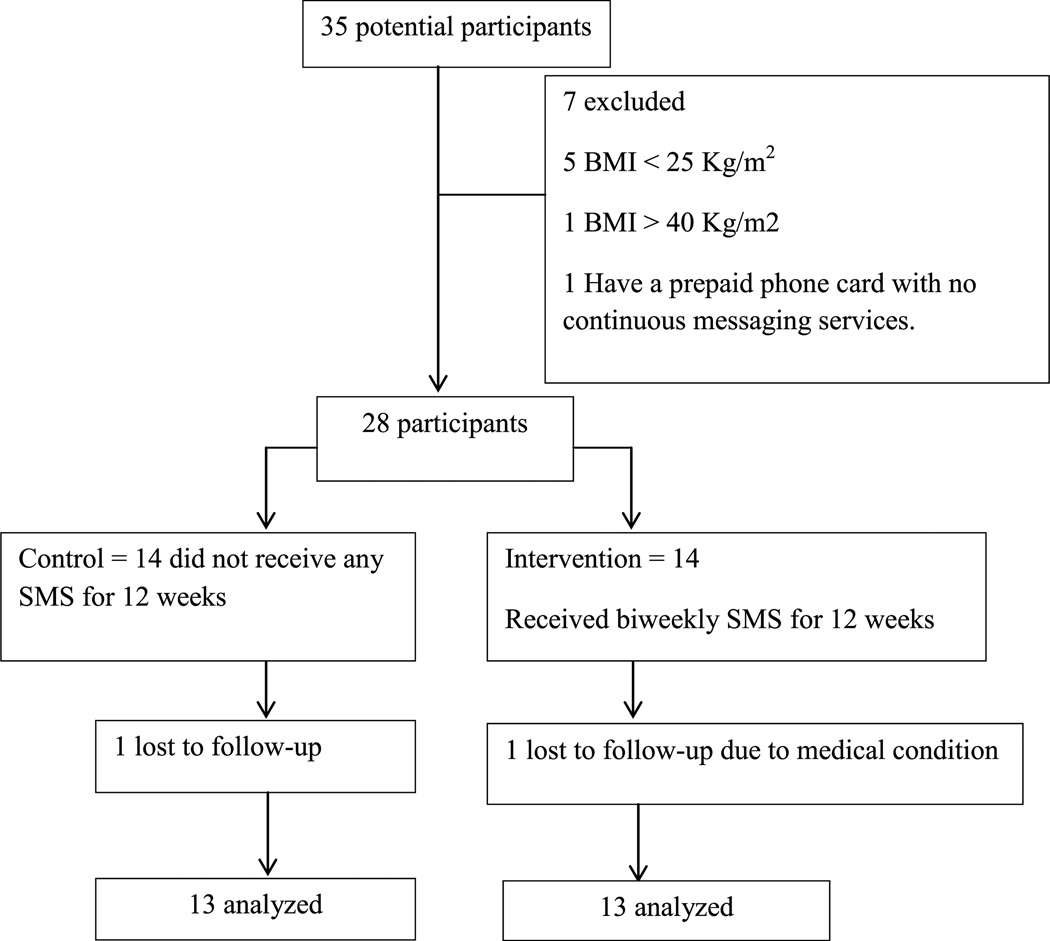

A total of 35 participants were recruited from “WW at work” group meetings on both campuses of Virginia Commonwealth University, during three consecutive weekly meetings, in June 2012 (Figure 1). Participants were eligible if they were healthy overweight or obese adults (body mass index [BMI] range of 25–40 kg/m2) and 18 years or older, owned a mobile phone with enabled text messaging service, and were enrolled in the “WW at work” program. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, a BMI less than 25 or greater than 40 kg/m2, and nonpossession of mobile phones.

FIGURE 1.

Study participant flowchart.

Intervention

All participants attended “WW at work” weekly meetings. An independent online health promotion company, Infield Health (http://www.infieldhealth.com), located in Washington, DC, initiated and implemented the intervention by sending biweekly SMS to the intervention group and storing participants’ responses in its database. Each message included 159 characters or fewer, suggested the application of a healthy behavior challenge, and ended by a “reply yes or no.” Participants were expected to text back “yes” upon completion of the requested behavior or “no” if they did not do it. They were also informed that they may text “stop” at any time they wished to opt out of the study. The content of messages was tailored to address the overall group’s perceived health and behavior barriers that hindered weight loss efforts as listed by participants on the baseline questionnaire. Identified barriers were related primarily to unhealthy eating behaviors, lack of time, inconsistency in exercise routine, and strong emotions altering healthy eating choices. Accordingly, during the 12-week intervention, each SMS varied in content, suggesting ways to adopt a healthy behavior and overcome a perceived barrier. For instance, participants referred to having poor food choices when hungry, so the suggested health challenge was to prepare food ahead of time or have handy a healthy snack. An example of the SMS they received was as follows: “Keep in the fridge a Ziploc with washed and precut vegetables 4 quick snack. Add 1 string cheese 4 proteins. Did u try it this week? Reply yes or no.” The control group did not receive any text messages.

Instruments and Outcome Measures

The assessment was done at baseline and at the end of the intervention at 12 weeks. Data were collected in June and September 2012. The outcome measures were body weight, eating behaviors, exercise and nutrition self-efficacy, social support, physical activity, and attitude toward technology. Body weight was measured by a trained WW staff, using a digital scale (Tanita C-400, Arlington Heights, IL), and was recorded on participants’ weight charts. Participants and researchers were not blinded to body weight. Height was self-reported. Eating behaviors were measured by the Weight Related Eating Questionnaire, which measures cognitive, emotional eating, and dietary restraints in relation to bodyweight.29 The Physical Activity and Nutrition Self-efficacy (PANSE) scale was used to measure exercise and nutrition self-efficacy among participants.30 Attitude toward technology was measured using questions adapted from the Technology Acceptance Model, which measures the perceived ease of use as well as the usefulness of the technology.31 Social support was measured by using questions adapted from the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List, which measures the perceived availability of social support resources.32 Physical activity was measured by the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short form and reported by the Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET)-minutes per week, computed by multiplying the MET score of an activity by the minutes performed.33 Adherence to the intervention was measured by the percentage of responses to prompting SMS requests. At the end of the intervention, participants evaluated the usefulness of SMS.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed in October 2012 with JMP Pro for Windows, version 10 (Cary, NC). On the basis of power analysis, with 80% power and a Cronbach’s α of .05, 30 subjects per group were needed to detect changes in the outcome variables preintervention to postintervention. In anticipation of lower sample size than the one needed to detect the difference, a one-sided P value was adopted stating that the intervention group would have greater weight loss and positive behavioral change as compared with the control group. Statistical analysis was performed excluding participants with missing follow-up data on the outcome measures. Summary statistics were used to describe the sample, including means, standard deviations, and ranges for the continuous variables and counts with frequencies for the categorical variables. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine any differences in baseline characteristics between groups for the continuous variables and Fisher exact test for the categorical variables. A mixed-model, repeated-measures ANOVA was used to detect any significant changes in outcome variables from baseline to 12 weeks, accounting for within-participant differences (time) and possible interaction effects (group × time). For repeated-measures ANOVA, the η2 was used to calculate the effect size.34

RESULTS

Participants

Thirty-five patients signed the consent form. Of the 35 participants, seven were excluded because they did not fulfill the inclusion criteria and two were lost to follow-up. Data from 26 participants were included in the final analysis (13 were in the intervention group and 13 in the control group). There was no difference between groups at baseline in sociodemographic characteristics and anthropometric or behavioral measures. The mean age for the intervention group was 46.6 years versus 42.5 years for the control group. The mean BMI for the intervention group was 33 kg/m2 versus 32.8 kg/m2 for the control group. The baseline characteristics of the two groups are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants by Group

| Participant Characteristics | Control, n (%) | Intervention, n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 42.5 ± 12.3 | 46.6 ± 11.8 | .37 |

| Gender: female | 13 (93) | 13 (93) | 1.0 |

| Race: white | 10 (72) | 8 (57) | .54 |

| Technology experience | 14 (29) | 14.4 (30) | .78 |

| Text messaging/week: 1–20 | 7 (50) | 5 (36) | .5 |

| Education: no college degree | 3 (21) | 4 (29) | .34 |

| Income: $25 000–$50 000 | 6 (43) | 4 (29) | .76 |

| Marital status: married | 7 (50) | 8 (57) | .82 |

| BMI, mean ± SD, kg/m2 | 32.8 ± 3.5 | 33 ± 4.8 | .92 |

| Weight, mean ± SD, lb | 193.4 ± 27.6 | 206.3 ± 35.6 | .29 |

| Eating behaviors | 44.5 (55.6) | 43.4 (54.2) | .72 |

| PANSE | 36.2 (82.2) | 33.9 (77) | .27 |

| Social support | 54.4 (85) | 54.5 (85.1) | .97 |

| Technology attitude | 20.3 (81.2) | 19.4 (77.6) | .65 |

| Total physical activity, mean ± SD, MET-min/wk | 2563.66 ± 916.35 | 2414.32 ± 561.15 | .89 |

| Sitting hours/day, mean ± SD | 8.00 ± 2.82 | 6.45 ± 2.69 | .17 |

| Total number | 14 | 14 |

Weight Change as a Health Outcome

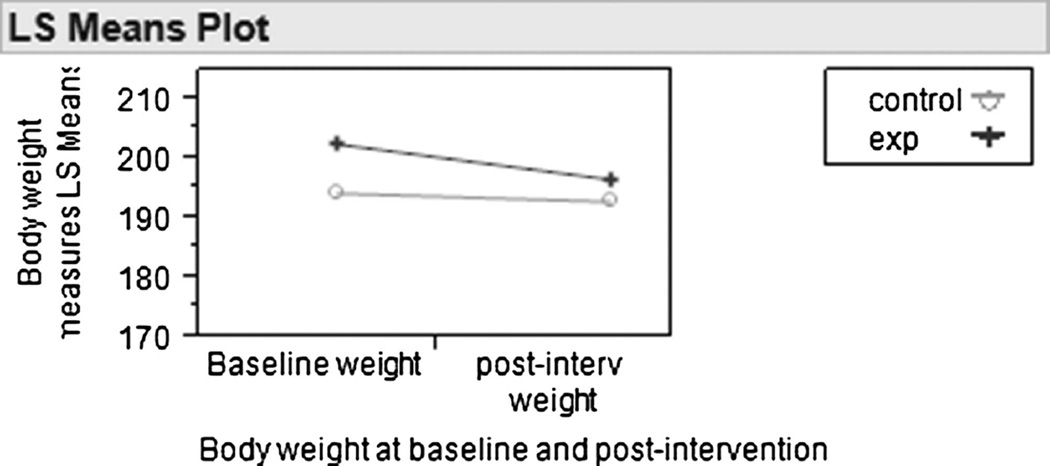

Mean body weights were compared between the two groups at 12 weeks and within group preintervention to postintervention (Table 2). The mixed-model repeated-measures ANOVA indicated that there was a significant weight loss at 12 weeks (F1,24 = 3.01, P = .047). The least squares means contrast indicated a significant weight loss in the intervention group (5.96 lb; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.14–9.79) as compared with the control group (1.41 lb; 95% CI, −2.41 to 5.24) (Figure 2). The effect of SMS on weight loss was 0.02, which is considered small according to the Cohen classification.35

Table 2.

Summary of Findings

| Variables | LS Mean | Standard Error | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control, baseline weight in lb | 194.18 | 8.49 | 176.69–211.68 |

| Control, postintervention weight in lb | 192.77 | 8.49 | 175.28–210.26 |

| Experimental, baseline weight in lb | 202.48 | 8.49 | 184.99–219.97 |

| Experimental, postintervention weight in lb | 196.51 | 8.49 | 179.02–214 |

| Control, baseline PANSE | 35.84 | 1.37 | 33.04–38.64 |

| Control, postintervention PANSE | 35.84 | 1.37 | 33.04–38.64 |

| Experimental, baseline PANSE | 33.84 | 1.37 | 31.04–36.64 |

| Experimental, postintervention PANSE | 36.69 | 1.37 | 33.89–39.48 |

| Control, baseline eating behaviors | 45.15 | 2.39 | 40.31–49.99 |

| Control, postintervention eating behaviors | 44.30 | 2.39 | 39.46–49.14 |

| Experimental, baseline eating behaviors | 42.84 | 2.39 | 38–47.68 |

| Experimental, postintervention eating behaviors | 47.69 | 2.39 | 42.85–52.53 |

| Control, baseline social support | 54.15 | 1.72 | 50.64–57.66 |

| Control, postintervention social support | 54 | 1.72 | 50.48–57.51 |

| Experimental, baseline social support | 54.38 | 1.72 | 50.87–57.89 |

| Experimental, postintervention social support | 54.3 | 1.72 | 50.79–57.81 |

| Control, baseline technology attitude | 20.07 | 1.32 | 17.37–22.77 |

| Control, postintervention technology attitude | 20.38 | 1.32 | 17.68–23.08 |

| Experimental, baseline technology attitude | 19.07 | 1.32 | 16.37–21.77 |

| Experimental, postintervention technology attitude | 19.69 | 1.32 | 16.99–22.39 |

| Control, baseline total PA MET-min/wk | 2482.7 | 957.82 | 441.15–4524.3 |

| Control, postintervention total PA MET-min/wk | 2410.6 | 957.82 | 368.98–4452.2 |

| Experimental, baseline total PA MET-min/wk | 2401.0 | 572.28 | 1180.8–3621.2 |

| Experimental, postintervention total PA MET-min/wk | 3093.3 | 767.32 | 1457.6–4729 |

| Control, baseline total hours of sitting/day | 8.00 | 0.71 | 6.36–9.32 |

| Control, postintervention total hours of sitting/day | 8.30 | 0.71 | 7.02–9.97 |

| Experimental, baseline total hours of sitting/day | 6.30 | 0.83 | 4.61–8.04 |

| Experimental, postintervention total hours of sitting/day | 6.35 | 0.81 | 4.66–8.03 |

Abbreviations: LS, least squares; PA, physical activity.

FIGURE 2.

Least squares mean plot for body weight.

Behavioral Outcomes

The changes in eating behaviors, exercise and nutrition self-efficacy, social support, physical activity, and attitude toward technology were also compared between the two groups at 12 weeks, and within group, using a mixed-model, repeated-measures ANOVA (Table 2). At 12 weeks, there was no significant difference in eating behaviors between groups (F1,24 = 2.34, P = .06). However, an improvement was detected in the eating behavior scores in the intervention and no change in the control group. Similarly, at 12 weeks, the intervention group scored higher than the control group on exercise and nutrition self-efficacy, but the difference between groups was not statistically significant (F1,24 = 2.46, P = .06). As for social support, there was no significant difference between groups (F1,24 = 0.0016, P = .48), nor a change from baseline scores in either group.

Physical activity was assessed by calculating the total MET-minutes per week spent in vigorous and moderate physical activity or walking, in addition to total weekly hours spent sitting. At 12 weeks, there was an increase in the total MET-minutes per week spent in physical activities in the intervention group but not in the control group, but the difference between groups was not significant (F1,9 = 0.22, P = .64). At 12 weeks, there was no significant difference between groups in the weekly hours of sitting (F1,24 = 0.71, P = .20), as well as any change from baseline scores in both groups. Furthermore, there was no significant difference between groups concerning attitude toward technology at 12 weeks (F1,24 = 0.04, P = .41) and no change from baseline scores in both groups.

Adherence to the Intervention

Adherence to the intervention was measured by calculating the total number of biweekly participants’ responses to health challenges over 12 weeks. Participants were considered adherent when they replied yes or no to a health challenge and nonadherent when they did not reply at all. At the beginning of the intervention, the participants’ response rate to SMS requests was 66%. This percentage declined to 52% at the end of the intervention.

Participant Feedback

At 12 weeks, participants in the intervention group answered five questions posed by the researchers asking if SMSs were motivational, the timing and frequency were acceptable, the ability to complete the health challenges, and if SMS helped in making good choices related to eating and exercise. Responses were categorized into “not at all,” “somewhat,” and “very much.” The content analysis of participant responses was related mainly to the timing of SMS. One participant wrote, “SMS would come mid-day when I was too busy to deal with.” Another participant commented, “SMS always come when I’m driving and I can’t do anything about it.” Some participants suggested allowing more time to complete the health challenges before asking if they completed it or not. In general, 72% of participants found SMS to be “somewhat” to “very motivational.” All participants agreed that the biweekly frequency of SMS was “somewhat” to “very much” acceptable. A total of 73% found that the timing of SMS was “somewhat” to “very much” adequate. A total of 80% of participants were able to complete the requested health challenges and 79% agreed that SMSs were “somewhat” to “very helpful” in making healthy choices related to eating and exercise.

DISCUSSION

Based upon findings from this study, the authors suggest that SMS mobile technology can be as effective a way to disseminate behavioral weight loss interventions as face-to-face behavioral interventions. The strength of this study resides in the SMS being the primary intervention, which differs from other weight loss studies that combined SMS with other behavioral components, making it difficult to assess its true effect.21–23 Despite a small sample size, participants in the intervention group were able to lose 4.5 lb more than the control group did. This weight loss is consistent with, if not greater than, results from previous studies using SMS intervention for weight management.20–22 Participants were able to achieve a total of 3% weight loss from their initial body weight, a percentage that compares favorably with previous research of 12 weeks’ duration.22,36–38 In addition, the retention rate was 96.4%, a high percentage when compared with similar studies,22,38,39 with respective attrition rates of 47%, 84.8%, and 87%.

At 12 weeks, the intervention group scored higher on exercise and nutrition self-efficacy and eating behaviors as compared with the control group and had an increase from baseline scores, demonstrating a positive behavioral trend but not sufficient statistical power to achieve significance (P = .06). Similarly, the intervention group had an increase in the total MET-minutes per week spent in physical activity, as compared with the control group, but this difference also did not reach statistical significance because of a small sample size. Both groups had high scores in attitude toward technology at baseline and at 12 weeks, with no significant difference between groups. This may be related to the fact that all participants were owners of mobile phones and were familiar with various technology features.

In the current study, social support scores did not improve from baseline in either group. Although the intervention group received encouragement statements by SMS upon completion of behavior challenges, all participants were receiving support in their weekly WW meetings. This might explain the reason for lack of change in social support scores because WW meetings can provide substantial support for both groups.40 In future studies, perceived social support can be further enhanced by offering participants online access to educational Web sites and virtual chat rooms or more interaction between participants and researchers.41,42

This pilot study has several limitations. The percentage of male participants was minimal, an aspect common in weight loss studies. Participants were not randomized but were selected depending on their meeting location to preserve group cohesiveness. All participants were enrolled in a weight loss program and were motivated to lose weight, thus limiting the generalizability of findings to the general population, who may not be motivated to lose weight or enrolled in a weight management program. The sample size was less than what was needed to have power to detect significant differences. This may have prevented some outcome measures such as exercise and nutrition self-efficacy, eating behavior, and physical activity from reaching statistical significance. Future studies with a larger sample size are needed to evaluate the true effect of SMS on behavioral changes. Exercise frequency, type, and duration were based on participants’ self-reports, which can be underestimated or overestimated. Future studies should combine self-reports with an objective measurement such as use of accelerometers for more accuracy.43 The current SMS intervention was not individually tailored, but rather addressed the overall group’s perceived barriers. Researchers suggest that individually tailored messages can enhance weight loss and increase adherence to the intervention.44,45 The lack of individualized SMS may as well explain the low rate of adherence among participants. The intervention was of short-term and limited to 12 weeks. Long-term follow-up trials with adequate sample size are needed to assess the efficacy of SMS in maintaining long-term behavioral changes and further explore innovative ways to optimize and increase the adherence to the intervention.

CONCLUSION AND SUMMARY

This pilot study was conducted to assess the effects of tailored SMS on body weight and behavioral changes in overweight and obese adults enrolled in a community weight management program. On the basis of the findings, this study adds to the existing knowledge that tailored SMS may enhance weight loss among overweight and obese adults and may increase exercise and nutrition self-efficacy, healthy eating behaviors, along with total time spent in physical activities. Companies, hospitals, and clinicians looking for efficient and innovative platforms to implement weight management interventions may consider using SMS to improve weight loss in overweight and obese adults.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Infield Health Company for supporting the study through the administration of the text messages to the intervention group. They also thank Mrs Debra Fitzgerald of Human Resources at Virginia Commonwealth University for her constant support throughout the study.

Footnotes

The authors have disclosed that they have no significant relationship with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Finkelstein E, Trogdon J, Cohen J, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Aff. 2009;28(5):w822–w831. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence V, Kopelman P. Medical consequences of obesity. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22(4):296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flegal K, Carroll M, Kit B, Ogden C. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galani C, Schneider H. Prevention and treatment of obesity with lifestyle interventions: review and meta-analysis. Int J Public Health. 2007;52(6):348. doi: 10.1007/s00038-007-7015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown T, Avenell A, Edmunds LD, et al. Systematic review of long-term lifestyle interventions to prevent weight gain and morbidity in adults. Obesity Rev. 2009;10(6):627–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodpaster B, Delany J, Otto A, et al. Effects of diet and physical activity interventions on weight loss and cardiometabolic risk factors in severely obese adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1795–1802. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spahn J, Reeves R, Keim K, et al. State of the evidence regarding behavior change theories and strategies in nutrition counseling to facilitate health and food behavior change. J AmDiet Assoc. 2010;110(6):879–891. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carels R, Darby L, Rydin S, Douglass O, Cacciapaglia H, O’Brien W. The relationship between self-monitoring, outcome expectancies, difficulties with eating and exercise, and physical activity and weight loss treatment outcomes. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30(3):182. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3003_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burke L, Wang J, Sevick M. Self-monitoring in weight loss: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(1):92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Del Corral P, Bryan D, Garvey WT, Gower B, Hunter G. Dietary adherence during weight loss predicts weight regain. Obesity. 2011;19(6):1177–1181. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abildso C, Zizzi S, Fitzpatrick S. Predictors of clinically significant weight loss and participant retention in an insurance-sponsored community-based weight management program. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(4):580–588. doi: 10.1177/1524839912462393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tufano J, Karras B. Mobile eHealth interventions for obesity: a timely opportunity to leverage convergence trends. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7(5):e58. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.5.e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Webber K, Tate D, Ward D, Bowling JM. Motivation and its relationship to adherence to self-monitoring and weight loss in a 16-week Internet behavioral weight loss intervention. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010;42(3):161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pellegrini C, Verba S, Otto A, Helsel D, Davis K, Jakicic J. The comparison of a technology-based system and an in-person behavioral weight loss intervention. Obesity. 2011;20(2):356–363. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Z, Fang L, Chen L, Dai H. Comparison of an SMS text messaging and phone reminder to improve attendance at a health promotion center: a randomized controlled trial. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2008;9(1):34–38. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B071464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishna S, Boren S, Balas EA. Healthcare via cell phones: a systematic review. Telemed E Health. 2009;15(3):231–240. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Car J, Gurol Urganci I, de Jongh T, Vodopivec Jamsek V, Atun R. Mobile phone messaging reminders for attendance at healthcare appointments. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD007458. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007458.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fjeldsoe B, Marshall A, Miller Y. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorton D, Dixon R, Maddison R, Mhurchu CN, Jull A. Consumer views on the potential use of mobile phones for the delivery of weight-loss interventions. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24(6):616–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2011.01163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haapala I, Barengo N, Biggs S, Surakka L, Manninen P. Weight loss by mobile phone: a 1-year effectiveness study. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(12):2382. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009005230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patrick K, Raab F, Adams M, et al. A text message-based intervention for weight loss: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(1):e1. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joo N, Kim B. Mobile phone short message service messaging for behaviour modification in a community-based weight control programme in Korea. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13(8):416–420. doi: 10.1258/135763307783064331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee C, Lee H, Jeon K, Hong Y, Park S. Self-management program for obesity control among middle-aged women in Korea: a pilot study. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2011;8(1):66–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7924.2010.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Renjilian DA, Perri MG, Nezu AM, McKelvey WF, Shermer RL, Anton SD. Individual versus group therapy for obesity: effects of matching participants to their treatment preferences. J Consult Clin Psychology. 2001;69(4):717–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller W, Franklin B, Nori Janosz K, Vial C, Kaitner R, McCullough P. Advantages of group treatment and structured exercise in promoting short-term weight loss and cardiovascular risk reduction in adults with central obesity. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2009;7(5):441–446. doi: 10.1089/met.2008.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pender NJ, Murdaugh CL, Parsons MA. Health Promotion in Nursing Practice. 5th. Upper saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heshka S, Anderson J, Atkinson R, et al. Weight loss with self-help compared with a structured commercial program: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289(14):1792–1798. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsai A, Wadden T. Systematic review: an evaluation of major commercial weight loss programs in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(1):56–66. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-1-200501040-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schembre S, Green G, Melanson K. Development and validation of a weight-related eating questionnaire. Eating Behav. 2009;10(2):119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Latimer L, Walker L, Kim S, Pasch K, Sterling B. Self-efficacy scale for weight loss among multi-ethnic women of lower income: a psychometric evaluation. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2011;43(4):279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis FD. A Technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End-User Information Systems: Theory and Results [dissertation] Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Sloan School of Management; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman H. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Social Support: Theory, Research, and Application. The Hague, the Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craig C, Marshall A, Sjöström M, et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olejnik S, Algina J. Generalized eta and omega squared statistics: measures of effect size for some common research designs. Psychol Methods. 2003;8(4):434–447. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.4.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDoniel S, Wolskee P, Shen J. Treating obesity with a novel hand-held device, computer software program, and Internet technology in primary care: the SMART motivational trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79(2):185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner McGrievy G, Campbell M, Tate D, Truesdale K, Bowling JM, Crosby L. Pounds Off Digitally study: a randomized podcasting weight-loss intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(4):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park M, Kim H. Evaluation of mobile phone and Internet intervention on waist circumference and blood pressure in post-menopausal women with abdominal obesity. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(6):388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnston J, Massey A, Devaneaux C. Innovation in weight loss programs: a 3-dimensional virtual-world approach. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(5):e120. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Witherspoon B, Rosenzweig M. Industry-sponsored weight loss programs: description, cost, and effectiveness. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2004;16(5):198–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2004.tb00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tate D, Jackvony E, Wing R. A randomized trial comparing human e-mail counseling, computer-automated tailored counseling, and no counseling in an Internet weight loss program. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(15):1620–1625. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Micco N, Gold B, Buzzell P, Leonard H, Pintauro S, Harvey Berino J. Minimal in-person support as an adjunct to internet obesity treatment. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33(1):49–56. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumahara H, Schutz Y, Ayabe M, et al. The use of uniaxial accelerometry for the assessment of physical-activity-related energy expenditure: a validation study against whole-body indirect calorimetry. Br J Nutr. 2004;91(2):235–243. doi: 10.1079/BJN20031033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rothert K, Strecher V, Doyle L, et al. Web-based weight management programs in an integrated health care setting: a randomized, controlled trial. Obesity. 2006;14(2):266–272. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bennett G, Herring S, Puleo E, Stein E, Emmons K, Gillman M. Web-based weight loss in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Obesity. 2010;18(2):308–313. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]