Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the merits and demerits of stapled skin closure when compared to conventional sutures in head and neck cancer surgery.

Materials and Methods

A total of 80 patients (40 patients each in control and study group) were enrolled. The patients underwent closure of incision wounds following head and neck cancer surgical procedures. Skin incisions were closed with sutures using 3-0 silk in control group and with stainless steel staples in study group. Both the groups were compared for speed of closure, cost effectiveness, pain on removal, patient comfort, aesthetic outcome on day of removal, 15 and 30 days after day of removal and complications.

Results

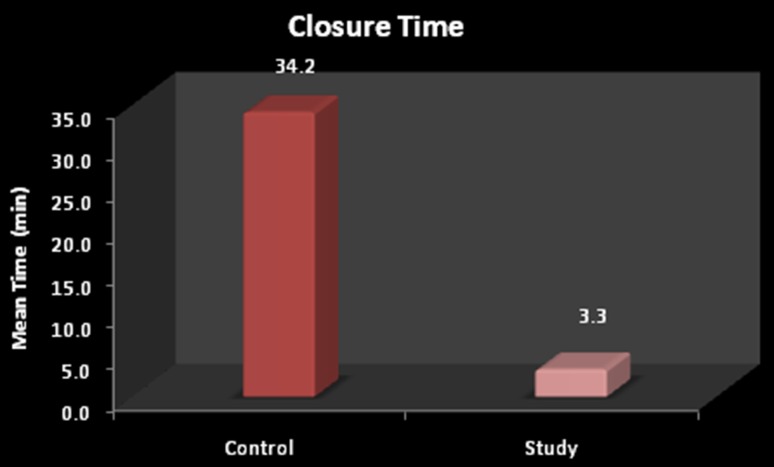

The mean incision length in control group was 54 ± 16.3 cm while in study group was 53.7 ± 15.4 cm which was statistically not significant (P = 0.95). The mean time of closure in control group was 34.2 ± 12 min while in study group was 3.3 ± 1.2 min which was statistically highly significant (P < 0.001). The mean cost of material for skin closure in control group was Rs. 270.0 ± 46.4 and in study group was Rs. 517.5 ± 135.7 which was also statistically highly significant (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

It was concluded that skin staples are better alternatives to conventional sutures in head and neck cancer surgery as they offer ten times faster wound closure, cost effectiveness, and similar results to sutures in terms of patient comfort, aesthetic outcome and complication rate.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer surgery, Skin closure, Sutures, Skin staples

Introduction

Historically, there were few surgical options for wound closure. From catgut, silk, and cotton, there is now an ever-increasing array of sutures, approximately 5269 different types, including antibiotic-coated and knotless sutures. Topical adhesives and skin staples are the recent closure methods which are developed to use either alone or in combination with traditional suturing techniques [1].

Ancient Hindus first used the insect mandibles to close skin wounds and this evolved the idea for development of staple wound closure. Mechanical suture devices were pioneered in the Soviet Union and introduced into the United States by Steichen and Ravitch in 1973 [2]. Stapling method of wound closure has been shown to be an excellent option in many situations [3].

Rapid and aesthetic healing of skin incisions requires accurate reapproximation of wound margins [4]. No technique can supersede standard suturing methods for closing wounds requiring the most meticulous repair. However, for most linear, non-facial lacerations, staples have been found to have the advantage of being faster, less damaging to host defenses, and useful in the management of potentially contaminated wounds [2].

As staples are being commonly used for incision wound closure in head and neck cancer surgery, there is a need to validate their efficacy in this specialty. So, a prospective trial was carried out to investigate the merits and demerits of stapled skin closure when compared with conventional sutures.

Objectives

The aim of present study was to compare staples and conventional sutures for:

Speed of wound closure

Cost effectiveness

Aesthetic outcome

Patient comfort

Pain on removal

Complication rate

Methodology

Source of Data

Eighty patients who attended the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery with histologically proven head and neck cancer requiring surgery were included in the study during the period of 2009–2012.

Detailed clinical histories along with routine necessary hematological and histopathological investigations for each patient were carried out. The selected patients were then informed of the surgery and method of closure of the surgical wound, its advantages and disadvantages.

Those who fulfilled and consented for the study were enrolled for the study.

Selection Criteria

This study followed the Declaration of Helsinki on medical protocol and ethics and the regional Ethical Review Board of the institute approved the study.

Inclusion Criteria

Incision wounds in patients undergoing head and neck cancer surgery.

ASA Class I and II patients.

Age: 25–65 years.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients on long term steroid and immunomodulator therapy.

ASA Class III and IV patients.

Patients who had previously undergone a neck exploration.

Armamentarium (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Armamentarium used

Skin stapler

3-0 Vicryl

3-0 Mersilk

Adson’s tissue holding forceps

Skin hooks

Needle holder

Staple remover

Scissors

Study Design

The study conducted was a double-blind, randomized and prospective study in which patients were randomized in both the groups using lottery method by an independent observer.

A total of 80 patients were enrolled. The patients underwent closure of incision wounds following head and neck cancer surgical procedures under general anesthesia. The incisions used for various surgical procedures in these patients were assigned to one of the following two groups (40 patients in each group):

Study group: Skin incisions closed with stainless steel staples.

Control group: Skin incisions closed with sutures using 3-0 silk.

Method

All the patients were operated for wide excision of tumor mass and neck dissection, either functional or radical depending upon the neck status of the individual. Reconstruction with pectoralis major myocutaneous flap (PMMC) was done in cases of wide excision of the tumor mass with radical neck dissection. After finishing with the procedure on the neck and chest, subcutaneous tissues were closed by using 3-0 vicryl in simple interrupted or continuous manner in both the groups.

In study group, skin was closed with stainless steel staples by placing a disposable stapler with arrow/mark on its head pointing along the incision line/wound edges while assistant surgeon had everted the wound edges using Adson’s tissue holding forceps. In control group, skin was closed with 3-0 silk cutting body by simple interrupted suturing technique in conventional manner. Following the completion of closure, an antiseptic medicated cream was applied followed with a protective dressing for the first 24–72 h. Drains were placed in all the cases and were kept till the drain content was minimal. All patients were given IV antibiotics (Cefotaxime + Sulbactam and Metronidazole) for 5–7 days postoperatively.

The closures were removed after an interval of 10–14 days, first removing the alternate sutures and then the remaining sutures after few days and pain on removal was recorded using VAS. Staples were removed using a staple remover that painlessly opened them sideways while sutures were removed in conventional manner. Patients were assessed on daily basis in immediate postoperative period and were followed up at the day of suture removal, 15 and 30 days after the suture removal for wound cosmesis, by an independent observer and, complications.

The data obtained in the study was tabulated under two groups assigned to each of the wound closure material used in the study.

The data obtained in the study included:

Time taken for closure The time taken for closure was calculated (in min) beginning from the placement of first skin staple or suture to the completion of last.

Total length of incisions Incision lengths used for the neck and chest surgical procedure were recorded (in cm) in immediate postoperative period by using a cotton thread and aligning it along the incision lines.

Material cost for skin closure The effective cost for the number of staples or suture packs used for skin closure was calculated (in Rs.).

Pain on removal of staples and sutures Patients were evaluated for pain on removal of staples and sutures using visual analogue scale having horizontal line running from ‘no pain’ (0 mm) to ‘worst pain’ (100 mm) on the questionnaires.

Aesthetic outcome Close photographs of the wounds were taken at the day of staple or suture removal and on 15 and 30 days after the removal and were analyzed by an independent blinded observer as poor, moderate or good.

Patient comfort Patient comfort was determined by asking difficulty in movement of the neck using VAS having same scale.

Complications Complications during immediate postoperative period and follow up were recorded, if any, as prolonged wound discharge, flap necrosis, wound dehiscence etc.

Statistics

Results are presented as Mean ± SD for quantitative data and as numbers and percentages for categorical data. Student’s unpaired t test was used for group wise comparisons. Categorical data was analyzed by Chi square test. A ‘P’ value of 0.05 or less was considered for statistical significance.

Results

Following were the Results and Observations Noted

Age and Sex

The study included total 80 patients—42 males and 38 females. In control group, 20 males and 20 females were there with mean age of 50.6 ± 8.4 years and range between 37 and 65 years with 12 patients (30 %) in age group of 35–45 years, 17 patients (42.5 %) in age group of 46–55 years and 11 patients (27.5 %) in age group of 56–65 years (Table 1). Out of 40 patients, 12 patients (30 %) underwent wide excision of the tumor with functional neck dissection while 28 patients (70 %) underwent wide excision of the tumor with radical neck dissection followed by reconstruction with PMMC flap (Table 2). 3-0 Mersilk was used for skin closure in all these patients.

Table 1.

Age distribution

| Age group | Control | Study | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 35–45 years | |||

| No. | 12 | 16 | 28 |

| % | 30.0 | 40.0 | 35.0 |

| 46–55 years | |||

| No. | 17 | 20 | 35 |

| % | 42.5 | 50.0 | 43.8 |

| 56–65 years | |||

| No. | 11 | 4 | 17 |

| % | 27.5 | 10.0 | 21.2 |

| Total | |||

| No. | 40 | 40 | 80 |

| % | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Chi square test, P value = 0.13 NS

Table 2.

Surgical procedures in two groups

| Procedure | Control | Study | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wide excision + FND | |||

| No. | 12 | 11 | 23 |

| % | 30.0 | 27.5 | 28.8 |

| Wide excision + RND + PMMC flap | |||

| No. | 28 | 29 | 57 |

| % | 70.0 | 72.5 | 71.2 |

| Total | |||

| No. | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| % | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Chi square test, P value = 0.81 NS

In study group, 22 males and 18 females were there with mean age of 47.4 ± 6.7 years and range between 35 and 64 years with 16 patients (40 %) in age group of 35–45 years, 20 patients (50 %) in age group of 46–55 years and 4 patients (10 %) in age group of 56–65 years (Table 1). Out of 40 patients, 11 patients (27.5 %) underwent wide excision of the tumor with functional neck dissection while 29 patients (72.5 %) underwent wide excision of the tumor with radical neck dissection followed by reconstruction with PMMC flap (Table 2). Skin stapler was used for skin closure in all these patients.

One patient expired in control group and two patients expired in study group during postoperative period due to reasons unrelated to method of closure.

Incision Length and Closure Time

The mean incision length in control group was 54 ± 16.3 cm while in study group was 53.7 ± 15.4 cm which was statistically not significant (P = 0.95). The mean time of closure in control group was 34.2 ± 12 min while in study group was 3.3 ± 1.2 min which was statistically highly significant (P < 0.001) (Table 3; Fig. 2). So the speed of wound closure was almost ten times faster in study group.

Table 3.

Incision length, cost, pain on removal and patient comfort

| Measurement | Group | Number | Mean | SD | t value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incision length (centimeters) | Control | 40 | 54.0 | 16.3 | 0.06 | 0.95, NS |

| Study | 40 | 53.7 | 15.4 | |||

| Cost (rupees) | Control | 40 | 270.0 | 46.4 | 10.92 | <0.001 %, HS |

| Study | 40 | 517.5 | 135.7 | |||

| Pain on removal (VAS) | Control | 39 | 2.15 | 0.9 | 0.30 | 0.70, NS |

| Study | 38 | 2.21 | 0.8 | |||

| Patient comfort (VAS) | Control | 39 | 3.9 | 1.8 | 0.97 | 0.34, NS |

| Study | 38 | 4.2 | 1.7 |

SD standard deviation

Fig. 2.

Closure time (in min) in both the groups

Material Cost for Skin Closure

The mean cost of material for skin closure in control group was Rs. 270.0 ± 46.4 and in study group was Rs. 517.5 ± 135.7 which was also statistically highly significant (P < 0.001) (Table 3). So it was found that the cost of material for skin closure was almost double for the study group.

Pain on Removal (Visual Analogue Scale Scores)

The mean VAS score for pain on removal in control group was 2.15 ± 0.9 while in study group was 2.21 ± 0.8 which was statistically not significant (P = 0.77) (Table 3).

Patient Comfort (Visual Analogue Scale Scores)

The mean VAS score for difficulty in moving the neck 1 week after the surgery in control group was 3.9 ± 1.8 while in study group was 4.2 ± 1.7 which was statistically not significant (P = 0.34) (Table 3).

Aesthetic Outcome

On Date of Removal

In control group, the scar was analyzed as good in 4 patients (10.3 %), moderate in 25 patients (64.1 %) and poor in 10 cases (25.6 %) while in study group, the scar was analyzed as good in 3 patients (7.9 %), moderate in 28 patients (73.7 %) and poor in 7 cases (18.4 %). Statistically there was no difference in wound cosmesis between the two groups on day of removal of sutures/staples (P = 0.66).

15 Days Post Date of Removal

In control group, the scar was analyzed as good in 7 patients (17.9 %), moderate in 27 patients (69.2 %) and poor in 5 cases (12.8 %) while in study group, the scar was analyzed as good in 9 patients (23.7 %), moderate in 24 patients (63.2 %) and poor in 5 cases (13.2 %). Statistically there was no difference in wound cosmesis between the two groups at 15 days after removal of sutures/staples (P = 0.81).

30 Days Post Date of Removal

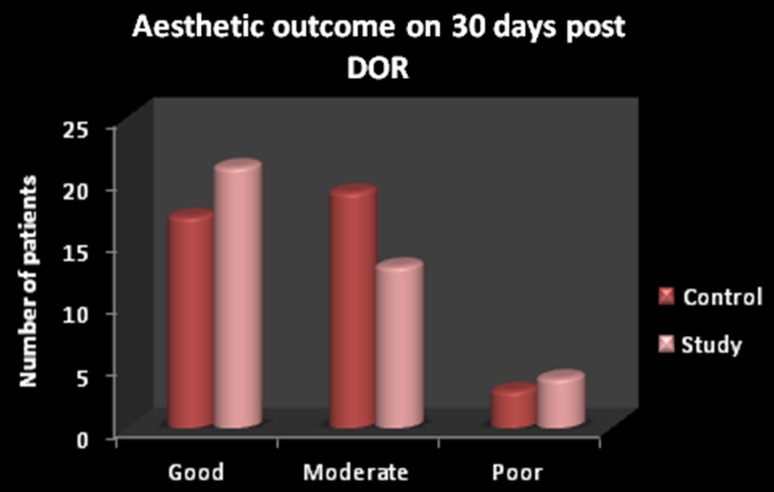

In control group, the scar was analyzed as good in 17 patients (43.6 %), moderate in 19 patients (48.7 %) and poor in 3 cases (7.7 %) while in study group, the scar was analyzed as good in 21 patients (55.3 %), moderate in 13 patients (34.2 %) and poor in 4 cases (10.5 %). Statistically there was no difference in wound cosmesis between the two groups at 30 days after removal of sutures/staples (P = 0.43) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Aesthetic outcome 30 days after removal of closures in both the groups

Complications

Two patients in study group and one patient in control group expired because of reasons unrelated to the method of closure. In control group, 31 out of 39 patients (79.5 %) were having no complications. Four patients (10.3 %) had wound dehiscence (Chest wound = 3, Neck wound = 1), one patient also had lip necrosis along with wound dehiscence. Four patients (10.3 %) were having prolonged wound discharge (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Post-operative complications in both the groups (WD wound dehiscence, PWD prolonged wound discharge)

In study group, 29 out of 38 patients (76.3 %) were having no complications. Seven patients (18.4 %) had wound dehiscence (Chest wound = 6, Neck wound = 1) and two patients (5.3 %) had prolonged wound discharge (Fig. 4). Statistically there was no difference in complications between the two groups (P = 0.73).

Discussion

Head and neck cancer surgeries comprise a marked number of surgical procedures in major parts of the world where tobacco usage is very frequent. These surgeries are often extensive because of carrying out reconstruction at the same time along with excision of the tumor mass and are quite exhausting for the operating surgeons. Use of staples for wound closure can be one of the ways to reduce the operating time as they achieve the desired results comparable to the conventionally used methods.

There are a number of well proved techniques of skin closure employing a variety of materials in use today (for example, suturing-interrupted or continuous using braided or monofilament materials, subcuticular closure using absorbable or non-absorbable sutures, metal clips of varying types and adhesive tapes). The choice of technique employed in any particular case is determined in part by the surgeon’s own preference and in part by the nature of the surgery performed (clean or dirty sites etc.) [5]. The factors which have to be considered in making a comparison of different types of wound closure are: the ease and speed with which the skin closure is completed, the level of patient discomfort, cost, the final cosmetic result and the complication rate [6].

Speed of Wound Closure

The mean incision length in control group was 54 ± 16.3 cm while in study group was 53.7 ± 15.4 cm which is statistically not significant (P = 0.95). The mean time of closure in control group was 34.2 ± 12 min while in study group was 3.3 ± 1.2 min which is statistically highly significant (P < 0.001). So the speed of wound closure was almost ten times faster in study group. In our study, all staple closures were placed by the same surgeon who was well versed with the technique. These results are in consistent with other studies which reported that stapling had the advantage of speed of execution [2, 7–10].

Cost Effectiveness

It was found that the cost for skin closure was almost double for the study group. This is because of good quality of staplers used and cost was compared according to the market prices. Above mentioned results are derived only from the cost of the material while the total cost of repair should include two components: cost of material and cost of labor. The cost of material used includes the expense of suture packs or staples used and the cost of labor includes operation theatre charges, anesthetist charges along with charges of theatre nurses and paramedical staff. Besides the above mentioned factors, surgeon’s time is one of the major factors influencing cost of labor. Cost of labor for each case is related to the time of closure. So longer the closure time, more will be the cost of labor. This finding is well supported by other studies [2, 7, 10–12].

Pain on Removal

We have not found removal of staples to be more painful than sutures as we had used a well designed staple remover which opened the staples sideways. Gatt et al. [12] found that routine staple removal was no more difficult or painful than suture removal in a study of abdominal wound closure. There are other studies in the literature showing that staples were more painful to remove [6, 8, 10]. Banwell et al. [13] suggested local application of EMLA cream 1 h before the removal of skin staples for a painless removal of skin staples and recommended this technique in all patients requiring the removal of skin staples.

Patient Comfort

The mean VAS score for difficulty in moving the neck 1 week after the surgery in control group was 3.9 ± 1.8 while in study group was 4.2 ± 1.7 which is statistically not significant (P = 0.34). Patients in both the groups who underwent reconstruction with PMMC flap following RND were having higher VAS scores because of the morbidity associated with the extended procedure and difficulty in moving the neck as the flap could restrict the neck movements to the opposite side while patients who underwent FND for management of neck were found to have lower VAS scores. So it is evident that patients who underwent FND for management of neck were more comfortable than the patients who underwent reconstruction with PMMC flap following RND and there is no statistically significant difference in the patient comfort between both the groups. These results are consistent with studies of Ridgway et al. [14].

Aesthetic Outcome

The scar cosmesis was evaluated in both the groups on the day of staple/suture removal, after 15 days, and after 30 days of removal (Figs. 5, 6, 7). There was no significant difference statistically in the wound cosmetics in both the groups on the day of removal, 15 and 30 days after the removal (P = 0.66, P = 0.81, and P = 0.43, respectively). Gatt et al. [12], George et al. [10], Medina dos Santos et al. [9], Selvadurai et al. [6] and Khan et al. [15] have also found that there was no difference in scar cosmetics with staple skin closure and other suture materials.

Fig. 5.

Pre-operative profile photograph of the patient in study group

Fig. 6.

Intra-operative profile photograph of the same patient

Fig. 7.

Post-operative profile photograph of the same patient

Complication Rate

Complications were reported in both the groups. These patients were managed by antibiotics and secondary suturing whenever required. Although there is no statistically significant difference between both the groups (P = 0.77) but there were more wound dehiscence in study group. All chest wound dehiscence were seen in male patients especially who were thin built and had scarce subcutaneous fat which resulted in inadequate flap mobilization leading to increased tension during wound closure. We did not observe any chest wound dehiscence in female patients in both the groups which may be due to presence of abundant adipose tissue that results in tension free wound closure after proper undermining. This was more pronounced in staple wound closure as they can cause crimping of skin edges and this mechanism is well explained by Coupland [16].

Conventional skin suturing techniques do have certain disadvantages, namely that a needle passing through the intact skin on either side of the wound carries both epidermis and organisms along its track and into the depths of the wound, thereby causing a higher incidence of wound infection than skin closure by a sutureless technique. This is especially so where a monofilament material is not used [5]. The conduction of surface bacteria by percutaneous multifilament sutures by wicking effect can also be a reason for infection [17]. Where the tension upon the wound edges is too great, due to either poor technique in inserting the sutures or subsequent tissue swelling after skin closure, localized ischemia results producing prominent cross-hatching along the scar and a poor cosmetic result. Skin closure employing metal clips avoids the problem of introducing infection deep into the wound but, by their very nature, clips do produce increased local tension and ischemia [5]. Johnson et al. [18] found that stapled wounds offered higher resistance to infection than sutured wounds.

Apart from the more efficient use of theatre time and saving in anaesthetic gases, the psychological effect on surgeon and theatre staff of rapid wound closure at the end of a long operation is also significant. There is also the inherent advantage of decreased exposure to needle-stick injuries using skin clip closure. According to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), American health care workers suffer between 600,000 and 1 million needle sticks and other sharps injuries every year. With more than 20 pathogens including HIV, hepatitis B and C transmittable through small amounts of blood, any protocol that results in less exposure to needle sticks should be welcomed. The case is particularly strong for the surgeons who have been estimated to have a cumulative lifetime risk of HIV seroconversion as high as 1–4 % [19].

Currently staples are widely used in orthopedics, scalp and abdominal surgeries and are also very helpful in securing grafts with or without the help of sutures. Advantages of staples include rapid placement, excellent cosmetic results, less tissue strangulation than sutures, minimal tissue reactivity, and low incidence of wound infections. Reported disadvantages of staples include interference with computed tomography scans, less meticulous approximation of wound edges in anatomically complex regions and the cost.

The ultimate responsibility for the choice of the best material lies with the surgeon. Choosing a method of closure that affords a technically easy and efficient procedure, with a secure closure and minimal pain and scarring, is paramount to any surgeon. From the results of this study, we suggest that skin staples are better alternative to conventional sutures in head and neck cancer surgery as they offer:

Ten times faster wound closure than sutures.

Cost effectiveness if total cost of closure is considered although cost of material was almost double than suture closure.

Similar results to sutures in terms of patient comfort, aesthetics outcome and complication rate.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge help and guidance of Dr Kirti Kumar Rai, Professor and Head, Dept. of OMFS, BDC&H, Davangere for his help and critical evaluation throughout the study.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Hochberg J, Meyer KM, Marion MD. Suture choice and other methods of skin closure. Surg Clin N Am. 2009;89:627–641. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orlinsky M, Goldberg RM, Chan L, Puertos A, Slajer HL. Cost analysis of stapling versus suturing for skin closure. Am J Emerg Med. 1995;13:77–81. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(95)90248-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Menaker GM (2001) Wound closure materials in the new millennium. Curr Probl Dermatol 13:90–95

- 4.Taute RB, Knepil GJ, Whitfield PH. Use of staples for wound apposition in neck incisions. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;47:236–237. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eaton AC. A controlled trial to evaluate and compare a sutureless skin closure technique (Op-Site Skin Closure) with conventional skin suturing and clipping in abdominal surgery. Br J Surg. 1980;67:857–860. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800671207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selvadurai D, Wildin C, Treharne G, Chowksy SA, Heywood MM, Nicholson ML. Randomised trial of subcuticular suture versus metal clips for wound closure after thyroid and parathyroid surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1997;79:303–306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suresh G, Rao KS, Sharma SM, Rajendra Prasad B. Use of skin staples in craniofacial and head and neck surgery: a prospective study. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2008;7(3):346–350. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stockley I, Elson RA. Skin closure using staples and nylon suture: a comparison of results. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1987;69:76–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medina dos Santos LR, Freitas CAF, Hojaij FC, Filho VJFA, Cernea CR, Brandao LG, et al. Prospective study using skin staplers in head and neck surgery. Am J Surg. 1995;170:451–452. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)80327-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George TK, Simpson DC. Skin wound closure with staples in the accident and emergency department. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1985;30(1):54–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doble A, Clark CLI, Lumley JSP. A comparative study between Michel and Proximate clips for the closure of neck incisions. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1991;73:204–206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gatt D, Quick CRG, Owen-Smith MS. Staples for wound closure: a controlled trial. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1982;67:318–320. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banwell P, Deakin M, Holden J, Powell B. Removal of skin staples and the use of EMLA cream. Br J Plast Surg. 1997;50:144–145. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1226(97)91334-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ridgway DM, Mahmood F, Moore L, Bramley D, Moore PJ. A blinded, randomized, controlled trial of stapled versus tissue glue closure of neck surgery incisions. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:242–246. doi: 10.1308/003588407X179062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan AN, Dayan PS, Miller S, Rosen M, Rubin DH. Cosmetic outcome of scalp wound closure with staples in the pediatric emergency department: a prospective, randomized trial. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18:171–173. doi: 10.1097/00006565-200206000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coupland RM. Sutures versus staples in skin flap operations. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1986;68:2–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stillman RM, Marino CA, Seligman SJ. Skin staples in potentially contaminated wounds. Arch Surg. 1984;119:821–822. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1984.01390190061013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson A, Rodeheaver GT, Durand LS, Edgerton MT, Edlich RF. Automatic disposable stapling devices for wound closure. Ann Emerg Med. 1981;10:631–635. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(81)80086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy M, Prendergast P, Rice J. Comparison of clips versus sutures in orthopaedic wound closure. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2004;14:16–18. doi: 10.1007/s00590-003-0121-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]