Abstract

Paragangliomas arising from the carotid body in the carotid bifurcation are termed as carotid body tumors. They are usually slow growing and asymptomatic. Considering the anatomical location, invasion or pressure on the adjacent vascular and neural tissues, the importance of early diagnosis and management is critical. In this article a case of carotid body tumor excised through transverse neck skin crease incision is presented along with literature review on the diagnosis, grading and different surgical approaches.

Keywords: Carotid body tumor, Paraganglioma, Lateral neck swelling, Surgical excision of CBT

Introduction

The carotid body, first described by Van Haller [1] in 1743, is located in the carotid adventia on the posterior aspect of the carotid bifurcation and is embryological derived from the neuro ectodermal tissue of the amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation system. The vascular neoplasms originating from the para ganglionic cells of the carotid bifurcation are termed CBT (carotid body tumor). Even though carotid body tumors are rare they are the first most common type of para ganglioma of head and neck region [2]. Frequently these tumors turn out to be malignant; hence operative intervention is the rule [2, 3]. Scudder was the first surgeon to successfully remove this tumor preserving the carotid system [4]. In 1940, Gordon-Taylor [5] showed subadventitial plane of tumor dissection. In this article surgical management of carotid body tumor through a modified transverse neck skin crease incision is presented. Diagnostic imaging modalities, anesthetic and post surgical complication are discussed.

Case Report

A 19 year old female patient reported to the hospital with a swelling in the right of the neck. She gave history of swelling present for past 1 year. Swelling gradually increased to present size. She had consulted a general surgeon 8 months back. Punch biopsy was done by him and the report was suggestive of para ganglioma. She also complained of amenorrhea for past 3 months.

Clinical examination revealed a single firm swelling in the right side of the neck, extending from lobule of ear to middle third of sternocledomastoid muscle. Swelling is mobile in the medio lateral plane and fixed in the supero inferior plane. On general examination she was apparently normal.

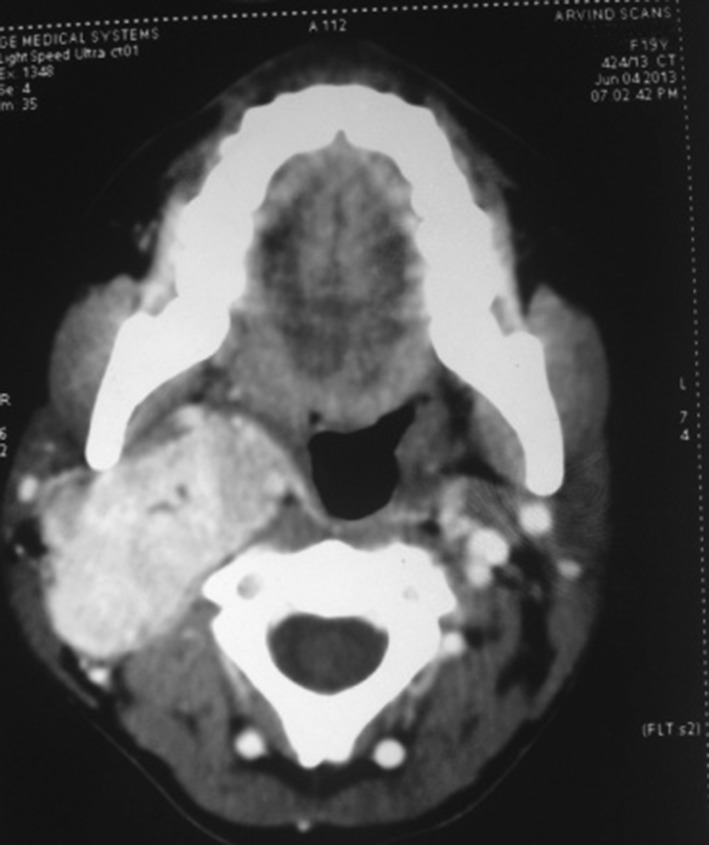

CT scan revealed a well defined, ovoid intensely enchasing isodense, solid mass over the posterior styloid compartment of right para pharyngeal space with splaying of carotid bifurcation and encasement of right internal carotid artery. The size of the lesion was around 5 cm supero-inferiorly and 4 cm in diameter i.e. medio-laterally.

Based on the clinical findings, CT scan and HPE report the lesion was confirmed as carotid body tumor. An obstetrics and gynecology opinion was obtained regarding amenorrhea which suggested it may be due to stress and was advised to go ahead with surgical removal of tumor.

A detailed pre anesthetic evaluation and psychological counseling was given to the patient. Patient was explained about the procedure and possible complications in their own language. After gaining patient’s confidence, she was taken up for surgery.

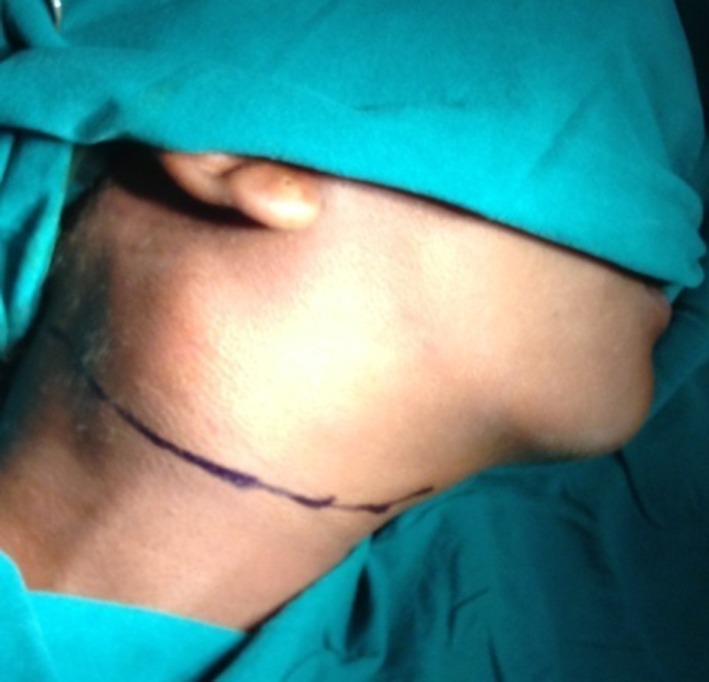

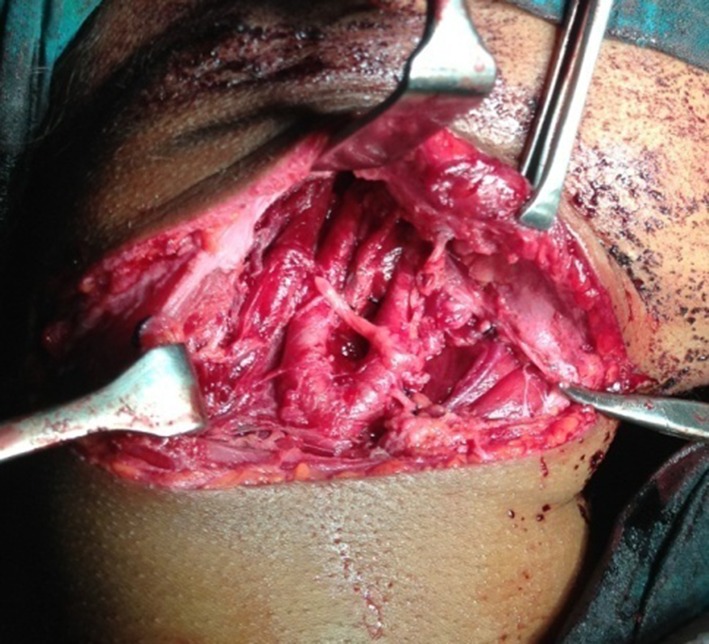

A modified transverse neck skin crease incision extending from midway of chin and superior border of cricoid cartilage to the post border of sternocledo mastoid muscle along the second skin crease of neck was placed (Fig. 1). The tumor was dissected from inferior to superior direction along the subadventitial plane preserving the integrity of carotid arteries. Hypoglossal nerve plastered to the tumor wall was carefully dissected and preserved. The common carotid artery was clamped using a bull dog clamp to reduce bleeding at the dissection site. Clamp was released every 10 min to maintain internal carotid artery (ICA) perfusion for few minutes. The tumor mass was excised in toto. After checking for thorough haemostasis, the wound was closed in layers with a suction drain in place (Figs. 2, 3, and 4).

Fig. 1.

Transverse neck incision

Fig. 2.

CT scan showing the lesion splaying the ICA and ECA

Fig. 3.

Axial cut showing obliteration of pharyngeal space

Fig. 4.

Lesion excised

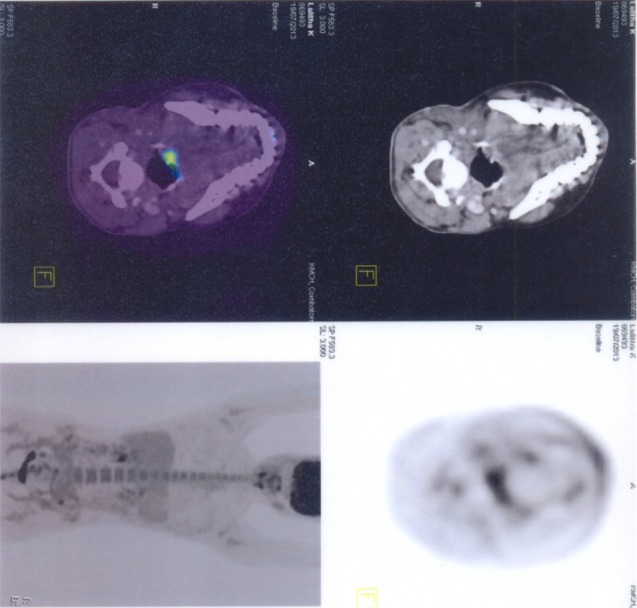

Wound healing was uneventful. Patient was apparently normal without any complaints at the time of discharge. Later she complained of hoarseness of voice and cough reflex while taking solid food. An ENT opinion was obtained. Endoscopic examination revealed right vocal cord palsy. She was advised certain exercises and told to consume food in head elevated position to avoid aspiration. Patient is being followed up for past one and half years and she is free of aspiration and coughing except for mild hoarseness of voice. One month after surgery a whole body PET scan was performed. It gave an impression of no definite evidence of metabolically active disease anywhere in the whole body. Two months after surgery patient had her menstrual cycle. A 24 h urine metanephrine test was done to rule out active paraganglomas in other sites and the results where negative.

Discussion

Carotid body tumors are extremely rare type of head and neck tumors. According to Seville Garcia et al. [6] incidence of tumour is 1–2 per 100,000. O’Neill et al. [7] in a retrospective review of 22 years in whole Northern Ireland reported only 29 patients with CBT. These tumours are slow growing and painless. Most of the time patient does not know the seriousness of tumour and present to the clinician at a late stage. Our patient also consulted her family physician at a late stage. The tumour manifests as a non tender, rubbery and pulsatile mass. The tumour can be moved medio laterally but not supero inferiorly as it is adherent to carotids (positive Fontaine sign) [7]. In our patient the tumour was not pulsatile, but Fontaine sign was positive. Even though CBT are slow growing tumours, they remain locally aggressive with growth rate of 2 cm every 5 years, which can lead to localized mass effects or neurological dysfunction due to pressure or infiltration [2, 8, 9]. Locally invasive growth of these tumors subsequently leads to cranial nerve deficits along with compression symptoms like Horner’s syndrome, syncope, hoarseness and dysphagia. Cranial nerve deficits particularly in 7, 9, 10, 11 or 12, can be seen in tumors that reach 5 cm in size [10–12]. Our patient had similar growth rate but the diameter of the lesion was only 4 cm and there was no neurological damage to above mentioned nerves.

Clinical diagnosis of CBT is usually confirmed with duplex ultrasound, CT, MRI and rarely conventional angiography [3, 13]. As our patient reported with HPE report of the tumor and CT scan with contrast no further investigation was done considering the poor financial background and unaffordability. CT was useful to predict the difficulty and possible complication of surgery. The tumor was graded as Shamblin’s classification type 2. As per Shamblin’s classification type 1 tumors are relatively small with minimal arterial attachment, type 2 tumors are those with moderate arterial attachment and partially surround the vessels and in type 3 tumors there is encasement of carotid bifurcation. Carotid body tumors are difficult to manage from both the anesthetist’s and surgeon’s aspect. Apart from intubation difficulty, which may be caused by tumor extending into hypo pharynx, injury to cranial nerves 9th, 10th, 12th may predispose to airway obstruction and aspiration [14].

Most of the surgeons in various centers around the world preferred a laterally inclined incision along the anterior border of the sternocledomastoid muscle. But we approached the tumor through modified transverse neck skin crease incision. As the patient was 19 years old and unmarried, we gave importance to aesthetic appearance. The transverse skin crease incision reduced the visibility of scar in the neck as it was hidden in the skin crease (Fig. 5) and shadow of neck. Another advantage of transverse neck incision is it can be extended to split the lip for access osteotomy of mandible. The mandible access osteotomy can be used to gain access to the tumors extending up to skull base along the internal carotid artery (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

a 1 year post-operative, b 1 year post-operative 12th nerve intact, c 1 year post-operative marginal mandibular nerve intact

Fig. 6.

Pet scan shows no evidence of metabolically active disease in whole body

Cerebrovascular complication such as stroke can occur while operating on CBT. The incidence has been reported to be 0–11 % [2, 15]. Carotid cross clamping may lead to arterial blood pressure changes and cerebral ischemia. The primary routes of collateral circulation are willisian channels (anterior and posterior communicating artery and the ophthalmic via external carotid artery) [16]. In our case the common carotid artery was clamped using a bulldog clamp to reduce bleeding. Patient did not develop stroke. This may be attributed to adequate collateral circulation through circle of Willis. If the clamping period is less than 10 min, the risk of developing neurological damage is very low as per Patetsis et al. [17]. Temporary balloon occlusion of the carotid artery to assess the adequacy of collateral circulation across the circle of Willis can be done at the time of carotid angiography [3]. Hypothermia reduces the cerebral metabolic rate for oxygen (CMRO2) by 6 % for every 1 °C reduction in brain temperature >28 °C. Mild hypothermia may suppress many of the chemical reactions associated with reperfusion injury. These reactions include free radical production, excitatory amino acid release, and calcium shifts, which can in turn lead to mitochondrial damage and apoptosis (programmed cell death). Considering the above facts mild hypothermia in the operative settings may give neuroprotection and prevent reperfusion injury [18–21].

Post operative cranial nerve injury usually correlates with the shambling classification of tumor. Specific nerves such as vagus are most often affected due to their close proximity to the tumors [7]. The hypoglossal and vagus nerve appeared to be most vulnerable to injury due to retraction or sacrifice [22]. Higher the Shamblin’s grade higher the neurological complication [23]. In our case the patient developed hoarseness of voice and repeated aspiration. This may be attributed to the recurrent laryngeal nerve (a branch of vagus nerve which supplies vocal cord) injury.

Preoperative embolization to reduce bleeding and shrink the tumor size is a topic of controversy; Dubois et al. [24] and Schick et al. [25] prefer routine preoperative embolization because it can lower blood flow and decrease tumor size. Vander Bogt et al. [26] and Litle et al. [27] disagree with routine embolization due to potential risk of stroke by emboli particle. The blood supply to CBT generally arises from the ECA. Hypotensive anesthesia may be used to reduce the intraoperative blood loss and get a good surgical field [7].

The malignant potential of CBT has been estimated to be around 5–10 %. Malignancy is determined by the detection of metastasis in local lymph nodes or remote organs such as lungs, bones, liver, pancreas, thyroid, breast and thorax rather than by the histological criteria or development of malignancy in neoplasm. The incidence of local or distant metastasis is less than 10 % [13, 28].

Conclusion

Carotid body tumor is rarely encountered by a maxillofacial surgeon. The anatomic location and relation of the tumor site pose a definitive risk for surgical management in terms of cerebrovascular and neurological complication. Adequate and precise preoperative investigations to know the exact size and anatomical relationship of the tumor are imperative for surgical planning and avoiding vascular and neurological complications. Dissection of the tumor in the sub adventitial plane reduces bleeding. Adequate back-up with a vascular surgeon will reduce the ischemia induced brain damage.

References

- 1.Van Halles Cited by Kohn A. Die. Paraganglion. Arch MiKr Anat 1903. 1743;62:263–268. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sajid MS, Hamilton G, Basker DM. A multicenter review of carotid body tumour management. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34(2):127–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jagtap SR, et al (2013) Carotid Body tumor excision: anesthetic challenges and review of literature. Indian J Anaesth 57(1):76–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Kaman L, Singh R, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to carotid body tumor: report of 3 cases and review of literature. Aust NZ J Surg. 1999;69:852–855. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.1999.01717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon-Taylor G. On carotid tumors. Br J Surg. 1940;28:163–172. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18002811003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sevilla Garcia MA, Llorente Pendas JL, et al. Head and neck paragangliomas; revision of 89 cases in 73 patients. Acta Otorinolaringol EsP. 2007;58:94–100. doi: 10.1016/S0001-6519(07)74888-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Neill S, et al. A 22-years Northern Irish experience of carotid body tumors. Ulster Med J. 2011;80(3):133–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathews FS. Surgery of the neck. In: Johson AB, editor. Operative therapeusis, chap 9. New York: Appleton-Crofts Inc; 1915. p. 315. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farr HW. Carotid body tumors: a 40 year study. CA Cancer J Clin. 1980;30(5):260–265. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.30.5.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaMuraglia GM, Fabian RL, Brewster DC, et al. The current surgical management of carotid body paragangliomas. J Vasc Surg. 1992;15:1038–1044. doi: 10.1016/0741-5214(92)90461-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotelis D, Rizos T, Geisbusch P, et al. Late outcome after surgical management of carotid body tumors from 20-years single centre experience. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:339–344. doi: 10.1007/s00423-008-0378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ilhan G, Bozok S, Ozpak B, et al. Diagnosis and management of carotid body tumor: a report of seven cases. Turk Gogus Kalp Damar Cerrahisi Dergisi. 2013;21(1):194–200. doi: 10.5606/tgkdc.dergisi.2013.6541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang SJ, et al. Surgical management of carotid body tumors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123(3):202–206. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.106709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wee DT, Goh CH. Current concepts in the management of carotid body tumors. Med J Malays. 2010;65:268–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luna-Ortiz K, et al. Does Shamblin’s classification predict postoperative morbidity in carotid body tumors? A proposal to modify Shamblin’s classification. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263(2):171–175. doi: 10.1007/s00405-005-0968-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baysal A, et al. Necessity of adequate monitoring during carotid body tumors. Anadolu Kardiyel Derg. 2010;10:376–381. doi: 10.5152/akd.2010.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patetsios P, Gable DR, et al. Management of carotid body paragangliomas and review of 30 years experience. Ann Vasc Surg. 2002;16:331–338. doi: 10.1007/s10016-001-0106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steen PA, Newberg L, Milde JH, et al. Hypothermia and barbiturates: individual and combined effects on canine cerebral oxygen consumption. Anesthesiology. 1983;58:527–532. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198306000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colbourne F, Sutherland G, Corbett D. Postischemic hypothermia: a critical appraisal with implications for clinical treatment. Mol Neurobiol. 1997;14:171–201. doi: 10.1007/BF02740655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ginsberg MD, Sternau LL, Globus MY, et al. Therapeutic modulation of brain temperature: relevance to ischemic brain injury. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev. 1992;4:189–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Safar PJ, Kochanek PM. Therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:612–613. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200202213460811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim J-Y, Kim J, Choi EC (2010) Surgical treatment of carotid body paragangliomas: outcomes and complications according to Shamblin’s classification. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 3(2):91–95. doi:10.3342/ceo.2010.3.2.91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Sen I, Stephen E, et al (2013) Neurological complications in carotid body tumor: a 6 year single center experience. J Vasc Surg 57:64S–68S [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Du Bois J, Kelly W, Mc Menamin P, Macbeth GA. Bilateral carotid body tumors managed with preoperative embolization: a case report and review. J Vasc Surg. 1987;5(4):640–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schick PM, et al. Arterial catheter embolization followed by surgery for large chemodetoma. Surgery. 1980;87(4):459–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vander Bogt KE, Vrancken Peeters MP, et al. Resection of carotid body tumor: results of an evolving surgical technique. Ann Surg. 2008;247(5):877–884. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181656cc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Litle VR, Reilly LM, Ramos TK. Preoperative embolization of carotid body tumor: when is it appropriate? Ann Vasc Surg. 1996;10(5):464–468. doi: 10.1007/BF02000594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McPherson GA, Halliday AW, Mansfield AO. Carotid body tumors and other cervical paragangliomas: diagnosis and management in 25 patients. Br J Surg. 1989;76:33–36. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800760111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]