Abstract

Objective

To assess the efficacy and safety of vaginal misoprostol after a pretreatment with vaginal estradiol to facilitate the hysteroscopic surgery in postmenopausal women.

Methods

In this observational comparative study, 35 control women (group A) did not receive any pharmacological treatment,26 women (group B) received 25 µg of vaginal estradiol daily for 14 days and 400 µg of vaginal misoprostol 12 hours before hysteroscopic surgery, 32 women (group C) received 400 µg of vaginal misoprostol 12 hours before surgery.

Results

Demographic data were well balanced and all variables were not significantly different among the three groups. The study showed a significant difference in the preoperative cervical dilatation among the group B (7.09±1.87 mm), the group A (5.82±1.85 mm; B vs. A, P=0.040) and the group C (5.46±2.07 mm; B vs. C, P=0.007). The dilatation was very easy in 73% of women in group B. The pain scoring post surgery was lower in the group B (B vs. A, P=0.001; B vs. C, P=0.077). In a small subgroup of women with suspected cervical stenosis, there were no statistically significant differences among the three groups considered. No complications during and post hysteroscopy were observed.

Conclusion

In postmenopausal women the pretreatment with oestrogen appears to have a crucial role in allowing the effect of misoprostol on cervical ripening. The combination of vaginal estradiol and vaginal misoprostol presents minor side effects and has proved to be effective in obtaining satisfying cervical dilatation thus significantly reducing discomfort for the patient.

Keywords: Cervical ripening, Estradiol, Hysteroscopy, Misoprostol, Postmenopause

Introduction

Hysteroscopic surgery is a minimally invasive approach and it is the most widely used method to treat intrauterine pathologies. Cervical dilatation is the first step in operative hysteroscopy and may be associated with cervical trauma. Half the complications such as cervical tears, uterine perforation, false tracks occur during cervical entry with the hysteroscope [1]. More frequently complications occur in nulliparous or in postmenopausal women. In postmenopausal women the passage through the cervical os may be very difficult and this may be related to reduced elasticity and increased cervical fibrosis caused by hormonal changes after menopause.

Recently, several studies have reported the use of misoprostol, a prostaglandin E1 analogue developed as an anti gastric ulcer drug and mostly used for cervical ripening before hysteroscopic procedures in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised studies comparing misoprostol versus placebo reported that vaginal misoprostol reduced the need for cervical dilatation in all premenopausal and postmenopausal women but when premenopausal and postmenopausal women were studied separately there was no significant difference between vaginal misoprostol and placebo. Moreover the side effects in the misoprostol group were significantly more frequent than in the placebo group, so the authors do not recommend the routine use of misoprostol before every hysteroscopy reserving its use for selected cases [2]. Another review showed there was not a beneficial effect of misoprostol on cervical dilatation or surgical complications and there was an increase of side effects in women treated with misoprostol undergoing operative hysteroscopy [3].

Most of the studies on misoprostol for cervical ripening prior to hysteroscopy had reported favorable effects in premenopausal women. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis clearly shows that misoprostol appears to facilitate hysteroscopic procedures only in premenopausal women [4].

In postmenopausal women, many studies have shown misoprostol alone is not effective for cervical ripening before hysteroscopy or dilatation and curettage [5,6,7,8] and only in a few studies misoprostol appears to be safe, effective, with mild side effects [9,10].

The best results with the use of misoprostol in premenopausal women have led to the hypothesis of a possible role of reproductive hormones on beneficial effect of misoprostol for cervical ripening. The pretreatment with oestrogen enhances the effects of misoprostol on cervical dilatation in postmenopausal women [11,12]. Atmaca et al. [11] evaluated the use of vaginal misoprostol in two groups one of which pretreated with oestrogen. In the study conducted by Oppegaard et al. [12], after two weeks of pretreatment with estradiol all women were randomised to receive misoprostol or a placebo. In both above-mentioned studies the combination of misoprostol and estradiol had a significant cervical ripening effect both versus misoprostol alone and estradiol alone.

The use of misoprostol in postmenopausal women is not well established and no solid conclusion has been reached.

We designed the present study to verify the usefulness of a cervical preparation with misoprostol prior to operative hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women and whether a pretreatment with vaginal estradiol enhances the effects of vaginal misoprostol on cervical ripening.

Materials and methods

Ninety-three postmenopausal women scheduled for operative hysteroscopy were included in the study at Day Surgery and Week Surgery Service, Section of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Tor Vergata University Hospital, Rome. Data were collected between September 2012 and June 2014. The study was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration for medical research involving human subjects and it was approved by the local ethical committee. All patients gave their written informed consent after a detailed explanation of the procedure.

Inclusion criteria were: postmenopausal women (>1 year since last menstruation), correct indication for operative hysteroscopy (polyps, myomas, endometrial thickening on ultrasound, and genital bleeding). Exclusion criteria included the presence of contraindications for operative hysteroscopy, recent or current pelvic infection, history of cervical surgery, known cervical malignancy, current use of hormone therapy with oestrogen, women that did not want to participate. Exclusion criteria for estradiol treatment were current breast or gynaecological cancer, contraindication for locally applied estradiol (women were included in group A and group C). Exclusion criteria for misoprostol treatment included any evidence of a contraindication for locally applied misoprostol, allergy to prostaglandins (women were included only in group A).

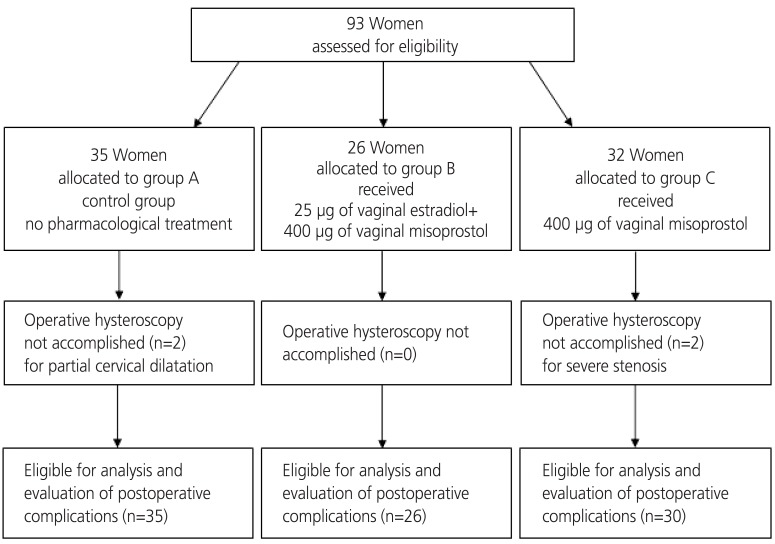

This was an observational comparative study. All women were allocated in three groups, as shown in Fig. 1. Women included in group A did not receive any pharmacological treatment (control group); women included in group B, self-administered estradiol vaginal tablets (Vagifem, Novo Nordisk Farmaceutici SpA, Rome, Italy; containing 25 µg of estradiol per tablet) once daily for 2 weeks before operative hysteroscopy and 400 µg of misoprostol (Cytotec, Pfizer Italia Srl, Latina, Italy; tablets of 200 µg) 2 tablets in vagina, as deep as possible, 12 hours before procedure; women included in group C self-administered 2 tablets of Cytotec deeply in vagina 12 hours before operative hysteroscopy. The drug administered was unknown to the surgeon who performed the hysteroscopic surgery. The patients were admitted in the morning on the day of surgery. The procedure was performed under general anaesthesia and prior to the hysteroscopy the operator was instructed in how to assess the preoperative cervical dilatation. All the procedures were performed by a single surgeon. A rigid unipolar 26-Fr resectoscope with an outer diameter of 8.7 mm and telescope 0° (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany) and unipolar loop electrode were used. The uterine cavity was distended with 5% sorbitol-mannitol solution and irrigation pressure, flow rate and suction pressure was electronically controlled by a combined suction and irrigation pump (Storz Hamou Endomat, Neuhausen ob Eck, Germany).

Fig. 1. Study flowchart.

Primary outcome measure was the cervical dilatation at the beginning of the procedure. The evaluation was performed by passing with Hegar dilators through the cervix starting with Hegar of size 2 mm. The diameter of the largest Hegar dilator passed through internal cervical os without any resistance felt by the operator was considered the preoperative cervical dilatation. Secondary outcomes included 1) type of dilatation judged as "very easy", "easy", "difficult", "impossible" by the operator; 2) symptoms and side effects before the hysteroscopy related to the pharmacological treatment such as pelvic cramps, vaginal bleeding, shivering, diarrhea, nausea, constipation, undissolved tablets of Cytotec in vagina; 3) complications during the hysteroscopy such as cervical tears, uterine perforation, false tracks; 4) severity of postoperative pain recorded by a visual analog scale (VAS). The VAS used consisted of a horizontal line of 10 cm in length, with the zero mark on the left represents "no pain" and the number ten marked the far right represents the "worst pain imaginable."

The sample size was estimated assuming an expected difference in the preoperative cervical dilatation >1 mm among groups with an standard deviation of the initial cervical width <2 mm. This difference was calculated to be apparent with at least 26 women in each group with an alpha error of 0.05 and a power of the test >80%.

Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS ver. 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented as the mean±standard deviation or median (range) for quantitative variables and frequency (percentage) for qualitative variables. Comparisons between the three groups were performed with multivariate general linear model-based one-way analysis of variance, Bonferroni's post hoc test was applied whenever appropriate. Categorical data were analysed by chi-square test or Fisher's exact test if the expected frequency was <5. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

Results

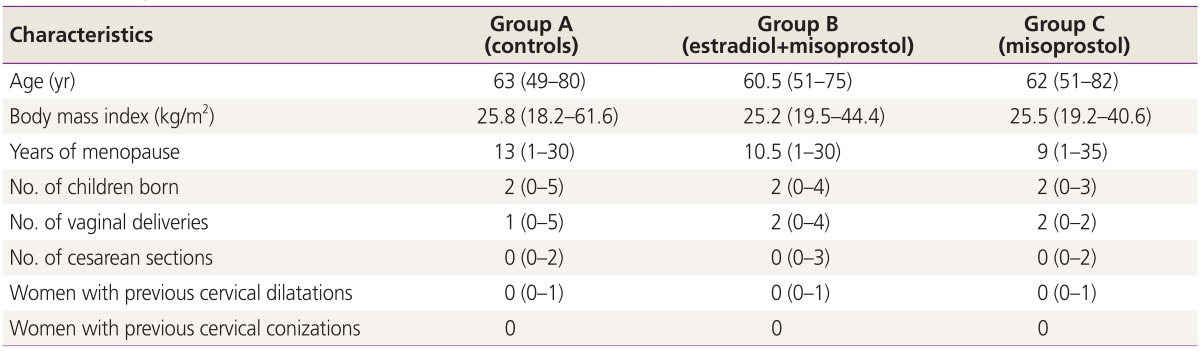

A total of 93 women entered the study protocol. Four women did not undergo operative hysteroscopy, two women in group A due to partial cervical dilatation, two women in group C due to severe stenosis (the last two were not included in the evaluation of the cervical dilatation at beginning of the procedure). Demographic data were well balanced and all variables shown in Table 1 were not significantly different among the three groups.

Table 1. Demographic data.

Data are presented as median (minimum–maximum).

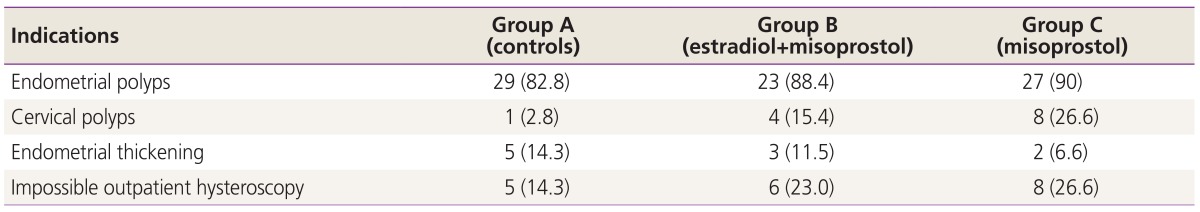

In Table 2 are shown the indications for operative hysteroscopy. Some women had more than one indication. "Endometrial thickening" was an indication for hysteroscopy in ten patients. In these women the histological findings were: endometrial polyps in seven women, leiomyoma in one woman, cystic atrophy in two women. In all other patients of the study, histological findings confirmed indications for operative hysteroscopy. Malignant diseases were not found.

Table 2. Indications for hysteroscopy.

Data are presented as raw numbers (percentage).

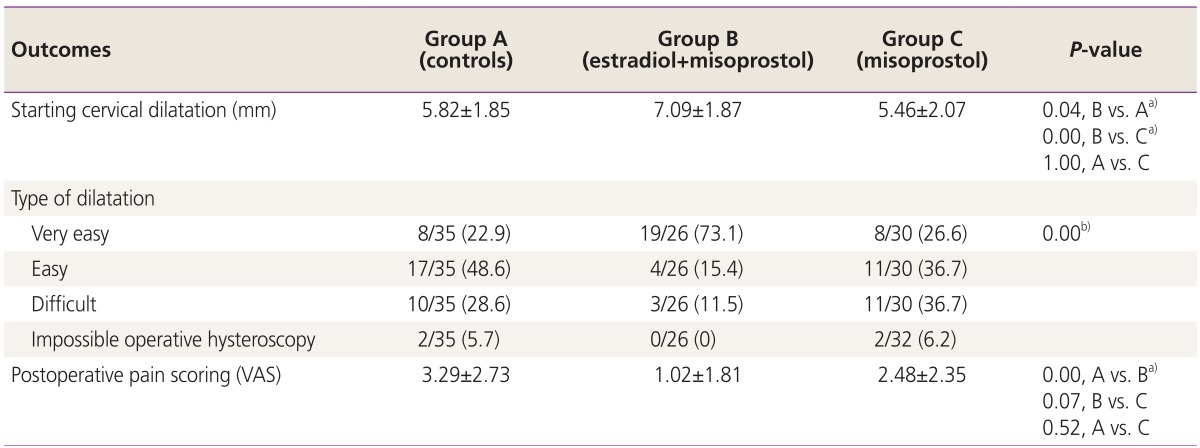

The mean cervical dilatation at the beginning of the procedure was 5.82±1.85 mm in the control group (A), 7.09±1.87 mm in the estradiol-misoprostol group (B), and 5.46±2.07 mm in the misoprostol group. The cervical dilatation was normally distributed in the three groups (bell curve), as shown in Table 3 there were statistically significant differences among the three groups (B vs. C, P=0.007; B vs. A, P=0.040).

Table 3. Main outcomes.

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation or as ratio (percentage).

VAS, visual analog scale.

a)ANOVA test; b)Chi-square test.

One of the secondary outcomes was the difficulty of cervical dilatation. In the group estradiol-misoprostol the dilatation was "very easy" in 73% of the procedures and, 54.3% of all dilatations "very easy" was in the group estradiol-misoprostol (odd ratio >2 respect to the others two groups). Few side effects were observed, one case of vaginal bleeding in the group A and in the group C respectively, one case of pelvic cramps in the group B and undissolved tablets of Cytotec in vagina in 3 women in the group C and 2 women in the group B.

Another secondary outcome was the severity of post surgery pain. A pain score based on a VAS from 0 to 10 was recorded 45 minutes after the procedure, with the patient awake, fully conscious and able to answer our questions. In group B (estradiol-misoprostol) pain scoring (VAS) was significantly lower than the control group (P=0.001) and lower than the group C as shown in Table 3.

In the subgroup of women in which it was impossible to perform the outpatient diagnostic hysteroscopy, normally performed without anesthesia or analgesia, because of a suspected cervical stenosis, the mean cervical dilatation at the beginning of the operative procedure was 3.00±1.40 mm in the control group (A), 5.50±2.40 mm in the estradiolmisoprostol group (B), and 3.60±2.10 mm in the misoprostol group. In this subgroup of women there were no statistically significant differences among the three groups considered. The pain seemed lower in the group B (P=0.046) but applying Bonferroni's test, the significance was lost because of the small number of women. No complications during and post hysteroscopy were observed.

Discussion

Misoprostol is a stable drug with a long half-life, it is inexpensive and available in oral tablet form. In premenopausal women the vaginal route appears to be superior to the oral route in terms of cervical dilatation [13]. By contrast, it has been reported that cervical widths and side effects were comparable regardless of the route of misoprostol administration [14,15] even if most of women preferred the oral route or had no preference [15]. On the other hand, the results on misoprostol alone before operative hysteroscopy in post-menopausal women are conflicting. It has been reported that a pretreatment with vaginal estradiol enhances the effects of vaginal misoprostol on cervical dilatation in postmenopausal women [11,12]. Mechanism of cervical ripening had not been clearly defined. The effect of estradiol on cervical priming may be related to the regulation of an inflammatory process mediated by cytokines [16].

The main objective of this study was to demonstrate that vaginal misoprostol after pretreatment with vaginal estradiol in postmenopausal women could result in a significant difference in cervical dilatation when compared to the vaginal misoprostol alone. The primary outcome was the measurement of cervical dilatation at the beginning of the procedure, a result that can be easily evaluated in connection with hysteroscopy. An outcome such as "type of dilatation" is quite subjective. This is the reason why in this study we considered only the operative hysteroscopies performed by a single operator who did not know neither the patients nor the drugs administered. Also the outcome "severity of postoperative pain" is a subjective parameter since the pain threshold is variable from patient to patient although the evaluation of this parameter could significantly improve the medical-surgical choices. In this study we considered only parameters that are easy to evaluate in routine surgical practice.

Our study compared three groups of women undergoing operative hysteroscopy. Our results showed that 400 µg of vaginal misoprostol administered 12 hours before operative hysteroscopy after a pretreatment for two weeks with vaginal estradiol is safe and significantly more effective for cervical preparation than 400 µg of vaginal misoprostol alone. Our findings are in good agreement with the results reported by Atmaca et al. [11] who have used 400 µg of oral misoprostol. Our results showed, however, that there was no difference in cervical dilatation between misoprostol group and control group and this observation suggests that in postmenopausal women estradiol is very useful, it enhances the effect of misoprostol in cervical preparation. Nevertheless, some questions remain to be clarified. In the study conducted by Oppegaard et al. [12], in the group of women treated with a combination of estradiol and 1,000 µg of misoprostol, the mean cervical dilatation at the beginning of operative hysteroscopy was 5.7±1.6 mm, which is similar to that found by Atmaca et al. [11] (4.4±07 mm) but lower than what was observed in our estradiol-misoprostol group (7.09±1.87 mm) and close to our misoprostol group (5.46±2.07 mm) and control group (5.82±1.85 mm). Perhaps, these differences may be due to the operator's experience or to the selection of patients. However, Kant et al. [10] found in postmenopausal women a mean cervical dilatation of 7.7±1.7 mm in a study group treated with only 200 µg of vaginal misoprostol inserted 12 hours before the procedure. Our observations showed that a combination of estradiol and misoprostol obtains a cervical dilatation at the beginning of the hysteroscopy similar to that observed in premenopausal women treated with 400 µg misoprostol regardless of the route of administration [14,15].

Fung et al. [6] found a higher incidence of undissolved medication in the misoprostol group than the placebo group. In an attempt to prevent this undesirable effect our patients were instructed to add water to misoprostol tablets to facilitate vaginal absorption.

The present observational study reported our clinical experience and it was designed to verify the routine use of misoprostol before every hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women. Our findings showed that the pretreatment with oestrogen seems to be useful and appears to be crucial in allowing the effect of misoprostol on cervical ripening. The combination of vaginal estradiol and vaginal misoprostol allows a "very easy" cervical dilatation in 73% of procedures, reduces women's pain, with mild side effects. The main strength of this study was to demonstrate that misoprostol before operative hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women should be used only after pretreatment with vaginal estradiol. In our study misoprostol was effective on cervical ripening only in the presence of oestrogen. A limitation of our study, however, is to have not measured the possible effect of estradiol alone. In the study conducted by Oppegaard et al. [12], all women received estradiol, and combination with misoprostol did improve the results. In contrary, in our study, misoprostol alone did not improve the results respect to no treatment, while estradiol seems to be crucial to facilitate the effect of misoprostol. Our findings lead us to believe that misoprostol is effective for cervical ripening only in association with endogenous or exogenous oestrogen levels as high as the ones reached during pregnancy, in premenopausal women with normal oestrogen levels or the ones reached after a pretreatment with estradiol in postmenopausal women. In agreement with Atmaca et al. [11] oestrogen treatment in women with presumed endometrial malignancy may be questionable even if a short duration of treatment, and the vaginal route of administration may eliminate the risk of its effects on endometrium. It must be stressed, however, that the combination of estradiol and misoprostol cannot be administered to all women (see our exclusion criteria) and it cannot be recommended to all postmenopausal women, its use must be reserved for selected cases. In postmenopausal women with symptom of bleeding diagnostic hysteroscopy with a diameter less than 3 mm may be more appropriate as a first step and if operative hysteroscopy is needed it can be performed as a next step. In our small subgroup of women, to whom it was not possible to perform an outpatient hysteroscopy for suspected cervical stenosis, there were no statistically significant differences among the three groups considered, only the pain seemed lower in the group estradiol-misoprostol. Further studies need to be performed to verify the usefulness of a combination of misoprostol and estradiol in women with suspected cervical stenosis.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Jansen FW, Vredevoogd CB, van Ulzen K, Hermans J, Trimbos JB, Trimbos-Kemper TC. Complications of hysteroscopy: a prospective, multicenter study. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:266–270. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00865-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gkrozou F, Koliopoulos G, Vrekoussis T, Valasoulis G, Lavasidis L, Navrozoglou I, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized studies comparing misoprostol versus placebo for cervical ripening prior to hysteroscopy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;158:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selk A, Kroft J. Misoprostol in operative hysteroscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:941–949. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31822f3c7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polyzos NP, Zavos A, Valachis A, Dragamestianos C, Blockeel C, Stoop D, et al. Misoprostol prior to hysteroscopy in premenopausal and post-menopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18:393–404. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ngai SW, Chan YM, Ho PC. The use of misoprostol prior to hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1486–1488. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.7.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fung TM, Lam MH, Wong SF, Ho LC. A randomised placebo-controlled trial of vaginal misoprostol for cervical priming before hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women. BJOG. 2002;109:561–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bunnasathiansri S, Herabutya Y, O-Prasertsawat P. Vaginal misoprostol for cervical priming before dilatation and curettage in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30:221–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2004.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oppegaard KS, Nesheim BI, Istre O, Qvigstad E. Comparison of self-administered vaginal misoprostol versus placebo for cervical ripening prior to operative hysteroscopy using a sequential trial design. BJOG. 2008;115:663, e1–e9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01628.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barcaite E, Bartusevicius A, Railaite DR, Nadisauskiene R. Vaginal misoprostol for cervical priming before hysteroscopy in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;91:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kant A, Divyakumar, Priyambada U. A randomized trial of vaginal misoprostol for cervical priming before hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women. J Midlife Health. 2011;2:25–27. doi: 10.4103/0976-7800.83263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atmaca R, Kafkasli A, Burak F, Germen AT. Priming effect of misoprostol on estrogen pretreated cervix in postmenopausal women. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2005;206:237–241. doi: 10.1620/tjem.206.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oppegaard KS, Lieng M, Berg A, Istre O, Qvigstad E, Nesheim BI. A combination of misoprostol and estradiol for preoperative cervical ripening in postmenopausal women: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2010;117:53–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batukan C, Ozgun MT, Ozcelik B, Aygen E, Sahin Y, Turkyilmaz C. Cervical ripening before operative hysteroscopy in premenopausal women: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of vaginal and oral misoprostol. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:966–973. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.03.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee YY, Kim TJ, Kang H, Choi CH, Lee JW, Kim BG, et al. The use of misoprostol before hysteroscopic surgery in non-pregnant premenopausal women: a randomized comparison of sublingual, oral and vaginal administrations. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:1942–1948. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song T, Kim MK, Kim ML, Jung YW, Yoon BS, Seong SJ. Effectiveness of different routes of misoprostol administration before operative hysteroscopy: a randomized, controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:519–524. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sennstrom MB, Ekman G, Westergren-Thorsson G, Malmstrom A, Bystrom B, Endresen U, et al. Human cervical ripening, an inflammatory process mediated by cytokines. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:375–381. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]