Abstract

Purpose

The decision to enroll in a clinical trial is complex given the uncertain risks and benefits of new approaches. Many patients also have financial concerns. We sought to characterize the association between financial concerns and the quality of decision making about clinical trials.

Methods

We conducted a secondary data analysis of a randomized trial of a Web-based educational tool (Preparatory Education About Clinical Trials) designed to improve the preparation of patients with cancer for making decisions about clinical trial enrollment. Patients completed a baseline questionnaire that included three questions related to financial concerns (five-point Likert scales): “How much of a burden on you is the cost of your medical care?,” “I'm afraid that my health insurance won't pay for a clinical trial,” and “I’m worried that I wouldn’t be able to afford the costs of treatment on a clinical trial.” Results were summed, with higher scores indicating greater concerns. We used multiple linear regressions to measure the association between concerns and self-reported measures of self-efficacy, preparation for decision making, distress, and decisional conflict in separate models, controlling for sociodemographic characteristics.

Results

One thousand two hundred eleven patients completed at least one financial concern question. Of these, 27% were 65 years or older, 58% were female, and 24% had a high school education or less. Greater financial concern was associated with lower self-efficacy and preparation for decision making, as well as with greater decisional conflict and distress, even after adjustment for age, race, sex, education, employment, and hospital location (P < .001 for all models).

Conclusion

Financial concerns are associated with several psychological constructs that may negatively influence decision quality regarding clinical trials. Greater attention to patients’ financial needs and concerns may reduce distress and improve patient decision making.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer treatment decision making is complex, requiring patients to balance the potential risks and benefits of treatments, often in the face of severe and life-threatening illnesses. From the psychosocial perspective, several factors may affect a patient’s ability to make an informed, high-quality treatment decision.1,2 Patients need to feel prepared to make relevant decisions.3,4 They may experience decisional conflict, which stems from uncertainty about different treatment options.5,6 They may have various levels of self-efficacy, which is their self-confidence or belief in their own ability to make important treatment-related decisions.7,8 In addition, individuals may experience different levels of distress, which can negatively affect decision quality.9

The rising costs of cancer care may further complicate decision making. Even well-insured patients can face high out-of-pocket costs. In addition, patients can face indirect costs, including lost wages, transportation, and child care. The American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends that physicians discuss the out-of-pocket costs with their patients.10 However, oncologists receive little training on how to counsel patients about their decision making in the setting of financial toxicity11,12 and are often unable to address their patients’ questions given the complexities of insurance coverage. Patients may also have barriers to discussing costs.13 Costs can be high; it is estimated that 13.4% of commercially insured patients with cancer spent over 20% of their after-tax income on medical care.14 These out-of-pocket costs may cause distress. In a cross-sectional study of 400 patients with cancer, 30% agreed that “I have concerns paying for my cancer treatment.” Twenty-two percent of patients responded that they agreed that, “My family has made financial sacrifices to pay for my cancer care.”15 In another study of 254 patients, of whom 75% contacted a national copayment assistance program, 42% reported that their cancer care represented a “significant catastrophic financial burden.”16 However, little is known about the impact of financial concerns on the ability of a patient with cancer to make informed, high-quality treatment decisions, such as the decision to enroll in a clinical trial.

In an effort to characterize the relationship between economic distress and a patient’s ability to make informed decisions about clinical trials, we analyzed data from a multi-institutional study of Preparatory Education About Clinical Trials (PRE-ACT), a Web-based educational intervention designed to address knowledge and attitudinal barriers to clinical trial participation. The study included three questions that assessed financial concerns. We hypothesized that greater financial concerns would be associated with greater distress regarding cancer and greater decisional conflict and would result in lower self-efficacy and preparation for decision making.

METHODS

PRE-ACT is a Web-based educational program designed to improve the preparation of patients with cancer for making decisions about clinical trial enrollment by delivering video content tailored to individual knowledge gaps and attitudes assessed by a baseline survey.17 The data used for this analysis are derived from a randomized clinical trial of PRE-ACT versus general text about clinical trials.18

Study Population

Adult patients with cancer were recruited from four National Cancer Institute–designated cancer centers in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Michigan between April 2010 and September 2012. Patients were approached before their first outpatient consultation with a medical oncologist. There was no restriction on disease site or prior treatment.

After providing informed consent, patients completed the baseline survey online, which included an assessment of knowledge and attitudes about clinical trials, as well as demographics, diagnosis, and treatment history. Decision-making measures included self-efficacy, preparation for decision making, and distress. Patients were randomly assigned to two arms: tailored video content that was based on their responses to the baseline survey or generic text about clinical trials. The baseline survey was completed before their physician consultation. After the consultation, they completed a postconsultation survey, which included a measure of decisional conflict. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating centers, and all participants provided informed consent.

Measurements

The baseline survey included three questions related to financial concerns: “How much of a burden on you is the cost of your medical care?” (Q1), “I'm afraid that my health insurance won't pay for a clinical trial” (Q2), and “I’m worried that I wouldn’t be able to afford the costs of treatment on a clinical trial” (Q3). Q2 and Q3 were asked again after the intervention.

All three questions were answered on a five-point Likert scale (“Not a burden” to “Extreme Burden” for Q1 and “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree” for Q2 and Q3). The results were summed (0 to 15), with higher scores indicating greater distress.

Psychosocial Constructs Relevant to Decision Making

Self-efficacy was adapted from the Decision Self-Efficacy Scale.19 This 11-item scale measures self-confidence or belief in one’s ability regarding decision making (ie, “I feel confident that I can get the facts about the risks and adverse effects of taking part in a clinical trial”). Higher scores indicate higher self-efficacy (range, 0 to 100).

Preparation for decision making was adapted from the Preparation for Decision Making Scale.4,20 This 10-item scale measures how useful a decision aid or other decision support intervention is in preparing a responder for communication with their health-care practitioner in making a health-care decision (ie, agreement with “You are prepared to make a decision about taking part in a clinical trial”). Higher scores indicate higher levels of perceived preparedness (range, 0 to 100).

Subjective distress was measured through the Impact of Event Scale.21 This is a 15-item instrument that measures responses to potentially stressful life events. Patients were asked to describe their feelings about their cancer within the prior week (ie, “I thought about it when I didn't mean to”). Higher scores indicate greater distress (range, 0 to 75).

Decisional conflict was measured using the Decisional Conflict scale.6 This 16-item scale measures the state of uncertainty a patient feels when confronted with decisions (ie, “I feel sure about what to choose”). Higher scores indicate greater decisional conflict (range, 0 to 100).

Analysis

Of 1,255 participants randomly allocated in the PRE-ACT study, this analysis focuses on the subset of 1,233 participants (98%) studied at baseline who answered one or more of the financial concern questions. In our primary analysis, we summed the three baseline cost concern responses, with higher numbers indicating greater concerns (Q1 + Q2 + Q3, range, 0 to 15). In our primary analysis, we included the responses of the 1,199 patients who answered all three questions. The Cronbach’s α was 0.61. Univariate relationships between financial concern measures and categorical demographic variables and psychosocial outcomes grouped by quartiles were examined using one-way analysis of variance or Kruskal-Wallis tests. Associations between continuous measures were examined with Pearson’s or Spearman correlations.

To determine factors related to a patient’s financial concerns, we first built univariate models with summary cost concern questions as outcomes of interest and the demographic variables and psychological constructs as the independent variables. We then built multivariable linear regressions with cost concerns as the outcome of interest. Demographic variables (age, race, sex, marital status, education, employment, hospital location) and each of the four psychological constructs (in separate models) were the independent variables. Because the decisional conflict scale was measured after the educational intervention, we also controlled for treatment arm in those models. In addition, we built univariate models with the psychosocial constructs as the outcomes of interest and the demographics and cost concerns as the independent variables.

Sensitivity Analyses

To determine whether our models were robust, we performed analyses using the sum of the two questions reflecting uncertainty regarding coverage and affordability (Q2 + Q3) as the dependent variable (1,210 patients answered both) and using the burden question (Q1; 1,122 patients) alone as the dependent variable. Because decisional conflict was measured after the intervention, we also measured the association between decisional conflict and the postintervention uncertainty questions (Q2 + Q3).

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

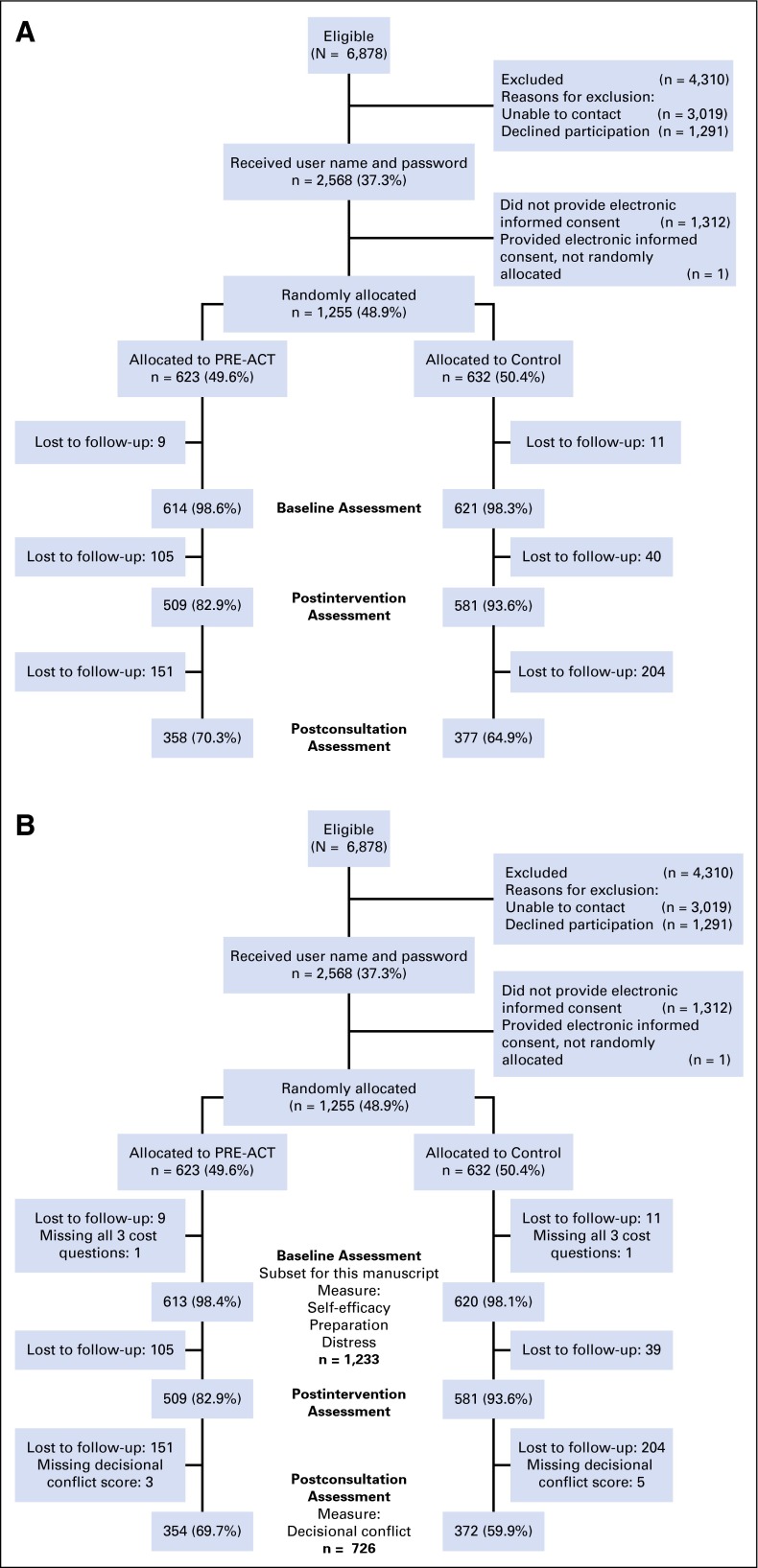

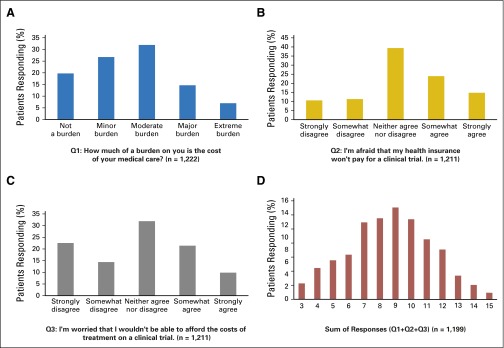

The CONSORT diagrams for the full study and the sample in this analysis are shown in Figure 1. Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1 for the 1,233 participants who answered any of the cost questions at baseline. Fifty-nine percent were women. Approximately one-quarter did not have education beyond high school. Fifteen percent were unemployed. Forty percent had metastatic disease; the most common were breast cancer (25%) and lung cancer (14%). Twenty-two percent reported that the cost of their care represented a “major” or “extreme” burden. Almost 40% of patients agreed with the statement, “I’m afraid my insurance won’t pay for a clinical trial,” and 30% agreed with the statement, “I’m worried that I won’t be able to afford the costs of treatment on a clinical trial.” The distribution of responses to the financial concern questions is shown in Figure 2.

Fig 1.

(A) CONSORT diagram for subset studied in this analysis. (B) CONSORT diagram for the full clinical trial. PRE-ACT, Preparatory Education About Clinical Trials.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| ≤ 65 | 901 | 73.07 |

| > 65 | 332 | 26.93 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 512 | 41.52 |

| Female | 721 | 58.48 |

| Race | ||

| Nonwhite | 142 | 11.52 |

| White | 1,088 | 88.24 |

| Missing | 3 | 0.24 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 29 | 2.35 |

| High school | 262 | 21.25 |

| More than high school | 941 | 76.32 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.08 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed/homemaker/student | 647 | 52.47 |

| Unemployed | 186 | 15.09 |

| Retired | 398 | 32.28 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.16 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/partnership | 914 | 74.13 |

| Not married/partnered | 318 | 25.79 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.08 |

| Hospital location | ||

| Illinois | 17 | 1.38 |

| Michigan | 196 | 15.90 |

| Ohio | 562 | 45.58 |

| Pennsylvania | 458 | 37.15 |

| Study arm | ||

| Control | 620 | 50.28 |

| PRE-ACT | 613 | 49.72 |

| Metastatic disease | ||

| No | 614 | 49.80 |

| Yes | 522 | 42.34 |

| Missing | 97 | 7.87 |

| Primary site | ||

| Breast | 317 | 25.71 |

| Colorectal | 126 | 10.22 |

| Lung | 176 | 14.27 |

| Pancreatic | 61 | 4.95 |

| Prostate | 104 | 8.43 |

| Other | 444 | 36.01 |

| Missing | 5 | 0.41 |

| Completed psychosocial construct measures | ||

| Self-efficacy | 1,208 | 84.3 (16.1)* |

| Preparation | 1,228 | 72.7 (15.5)* |

| Distress | 1,206 | 28.7 (15.5)* |

| Decisional Conflict | 726 | 21.9 (17.6)* |

Abbreviation: PRE-ACT, Preparatory Education About Clinical Trials.

Mean (standard deviation).

Fig 2.

Cost concerns responses: (A) Q1, “How much of a burden on you is the cost of your medical care?”; (B) Q2, “I'm afraid that my health insurance won't pay for a clinical trial”; (C) Q3, “I’m worried that I wouldn’t be able to afford the costs of treatment on a clinical trial”; and (D) Sum of responses.

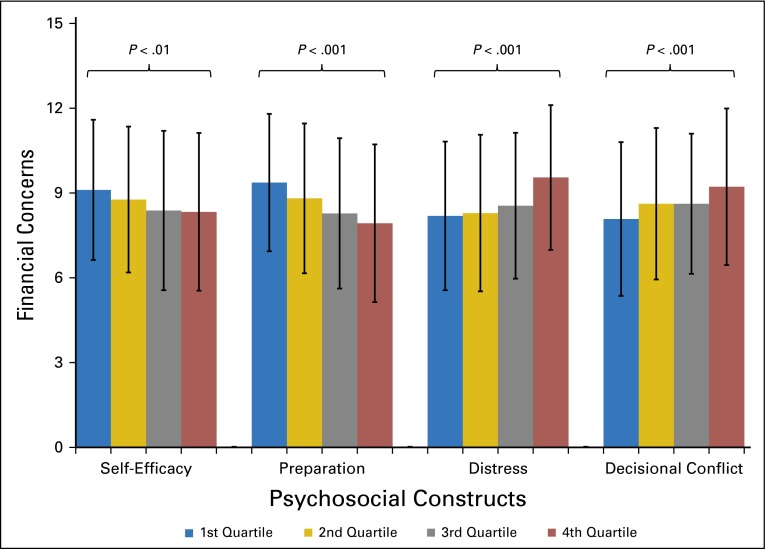

The results of the univariate models describing associations between cost concerns (Q1 + Q2 + Q3) and the demographic and psychosocial variables are listed in Table 2. Female sex, younger age, less education, being unemployed, and being not married or partnered were associated with greater cost concerns. There was no association between presence of metastatic disease or primary site of disease and cost concerns. Figure 3 shows the mean financial concern by score quartile of the psychosocial constructs. There was a strong association for all four constructs; patients with greater financial concerns had lower self-efficacy (P = .004) and preparation (P < .001) and greater distress (P < .001) and decisional conflict (P < .001). Results of the univariate analyses using the uncertainty questions were similar (Q2 + Q3). Results using the burden question (Q1) were similar except that hospital location was predictive of greater burden, with patients from Ohio reporting the greatest burden. However, self-efficacy, preparation, and decisional conflict were not associated with greater burden (Appendix Table A1, online only).

Table 2.

Univariate Relationships Between Summary Cost Concerns and Demographics and Psychosocial Constructs Scores

| Characteristic | Summary | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (Standard Deviation) | P | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 8.45 (2.68) | .04 |

| Female | 8.77 (2.68) | |

| Age, years | ||

| ≤ 65 | 8.86 (2.67) | < .001 |

| > 65 | 8.03 (2.63) | |

| Race | ||

| Nonwhite | 8.89 (2.68) | .25 |

| White | 8.61 (2.69) | |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 9.96 (2.44) | .01 |

| High school | 8.86 (2.67) | |

| More than high school | 8.54 (2.69) | |

| Employment | ||

| Employed/homemaker/student | 8.72 (2.70) | < .001 |

| Unemployed | 9.33 (2.62) | |

| Retired | 8.19 (2.63) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/partnership | 8.52 (2.70) | .01 |

| Not married/partnered | 8.97 (2.62) | |

| Hospital location | ||

| Pennsylvania | 8.40 (2.69) | .05 |

| Illinois | 8.00 (2.53) | |

| Michigan | 8.68 (2.45) | |

| Ohio | 8.84 (2.76) | |

| Metastatic disease | ||

| No | 8.56 (2.75) | .63 |

| Yes | 8.64 (2.59) | |

| Primary site | ||

| Breast | 8.63 (2.90) | .78 |

| Colorectal | 8.66 (2.52) | |

| Lung | 8.79 (2.64) | |

| Pancreatic | 8.46 (2.77) | |

| Prostate | 8.31 (2.66) | |

| Other | 8.68 (2.60) | |

| Self-efficacy score, quartile | ||

| First | 9.11 (2.48) | < .01 |

| Second | 8.77 (2.58) | |

| Third | 8.38 (2.82) | |

| Fourth | 8.33 (2.78) | |

| Preparation score, quartile | ||

| First | 9.37 (2.43) | < .001 |

| Second | 8.81 (2.65) | |

| Third | 8.28 (2.66) | |

| Fourth | 7.93 (2.79) | |

| Distress score, quartile | ||

| First | 8.19 (2.63) | < .001 |

| Second | 8.29 (2.77) | |

| Third | 8.55 (2.58) | |

| Fourth | 9.55 (2.56) | |

| Decisional conflict score, quartile | ||

| First | 8.08 (2.72) | < .001 |

| Second | 8.62 (2.68) | |

| Third | 8.62 (2.48) | |

| Fourth | 9.22 (2.77) | |

NOTE. P value is from one-way analysis of variance.

Fig 3.

Associations between financial concerns and psychosocial constructs, by quartile (P value from analysis of variance).

The results of the multivariable models are listed in Table 3. In all four of the individual models, greater financial concern was associated with worse decision-making outcomes as measured by the psychosocial constructs. Hospital location, education, sex, and employment status were also associated with greater financial concerns in individual models (Table 2).

Table 3.

Multivariable Analyses by Psychosocial Construct

| Parameter | Self-Efficacy | Preparation | Distress | Decisional Conflict | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (95% CI) | P | Estimate (95% CI) | P | Estimate (95% CI) | P | Estimate (95% CI) | P | |

| Self-efficacy | −0.02 (−0.03 to −0.01) | < .001 | −0.04 (−0.05 to 0.03) | < .001 | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.04) | < .001 | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.04) | < .001 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 0.22 (−0.09 to 0.54) | .16 | 0.26 (−0.04 to 0.57) | .09 | 0.05 (−0.27 to 0.37) | .75 | 0.21 (−0.20 to 0.62) | .31 |

| Male | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Race | ||||||||

| Nonwhite | 0.09 (−0.40 to 0.58) | .71 | 0.08 (−0.40 to 0.56) | .73 | 0.10 (−0.39 to 0.58) | .70 | −0.34 (−0.97 to 0.30) | .30 |

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Education | ||||||||

| More than high school | −1.20 (−2.21 to −0.19) | .02 | −1.21 (−2.21 to −0.22) | .02 | −1.07 (−2.11 to −0.02) | .05 | −0.72 (−2.19 to 0.74) | .33 |

| High school | −0.93 (−1.97 to 0.12) | .08 | −0.99 (−2.02 to 0.04) | .05 | −0.80 (−1.88 to 0.28) | .15 | −0.75 (−2.25 to 0.75) | .33 |

| Less than high school | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Employment | ||||||||

| Retired | −0.10 (−0.53 to 0.32) | .63 | −0.14 (−0.55 to 0.28) | .52 | −0.16 (−0.58 to 0.27) | .47 | −0.12 (−0.66 to 0.42) | .66 |

| Unemployed | 0.53 (0.08 to 0.98) | .02 | 0.56 (0.12 to 1.00) | .01 | 0.42 (−0.03 to 0.87) | .07 | 0.43 (−0.17 to 1.03) | .16 |

| Employed/homemaker/student | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Age, years | ||||||||

| > 65 | −0.65 (−1.09 to −0.21) | .004 | −0.74 (−1.17 to −0.31) | < .001 | −0.57 (−1.00 to −0.13) | .01 | −0.97 (−1.52 to −0.41) | < .001 |

| ≤ 65 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married/partnership | −0.29 (−0.64 to 0.06) | .11 | −0.31 (−0.66 to 0.03) | .07 | −0.32 (−0.67 to 0.03) | .07 | −0.12 (−0.59 to 0.35) | .62 |

| Not married/partnered | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Hospital location | ||||||||

| Illinois | −0.44 (−1.75 to 0.87) | .51 | −0.49 (−1.78 to 0.80) | .46 | −0.19 (−1.50 to 1.11) | .77 | −0.78 (−2.75 to 1.19) | .44 |

| Michigan | 0.37 (−0.09 to 0.83) | .11 | 0.26 (−0.19 to 0.71) | .26 | 0.27 (−0.19 to 0.72) | .25 | 0.24 (−0.33 to 0.80) | .41 |

| Ohio | 0.46 (0.13 to 0.80) | .007 | 0.43 (0.10 to 0.76) | .009 | 0.53 (0.20 to 0.86) | .002 | 0.41 (−0.03 to 0.85) | .07 |

| Pennsylvania | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Study arm | ||||||||

| Control | 0.20 (−0.18, 0.58) | .31 | ||||||

| PRE-ACT | Ref | |||||||

Abbreviations: PRE-ACT, Preparatory Education About Clinical Trials; Ref, reference.

There were similar findings with the responses to the burden questions (Q1) and the two questions regarding uncertainty (Q2 + Q3). The association between the financial concerns and psychological constructs were all statistically significant on multivariable analyses, with the exception of burden (Q1) and self-efficacy (Appendix Tables A2-A3). In addition, the association between decisional conflict and the uncertainty questions measured at baseline and after intervention (Appendix Table A4) were similar.

We measured the univariate associations between psychosocial constructs and demographics and cost concerns (Appendix Table A5). The associations varied across the constructs. For example, being older and male were both associated with greater decisional conflict, whereas being younger and female were associated with greater distress.

DISCUSSION

In this multi-institutional sample of more than 1,200 patients with cancer, we found a high prevalence of financial concerns related to the overall burden of cancer care and cost concerns related specifically to clinical trials. Greater concerns were associated with worse scores on psychosocial measures that are considered essential for informed, patient-centered decision making. Specifically, patients with greater concerns expressed greater distress and decisional conflict and lower self-efficacy and preparation for decision making. These results remained significant, even when controlling for sociodemographic factors such as age, sex, race, education, and employment status or state where the treatment center was located. These findings were not isolated to patients with metastatic disease or a specific tumor type, suggesting that these concerns are found among patients across the disease trajectory. These findings underscore the importance of assessing and addressing patient financial concerns throughout the treatment decision-making process.

These results are significant for several reasons. Cancer treatment decision making, such as the decision to enroll in a clinical trial, requires patients to balance many factors and personal preferences with regard to efficacy, toxicity, and cost. Decision aids such as PRE-ACT have been developed to help patients make complex treatment decisions. Their efficacy is measured typically in their ability to improve preparation and self-efficacy and reduce distress and decisional conflict. However, such aids have not been developed to guide patients in integrating financial concerns into treatment decision making. Several trends have resulted in increased costs for patients with cancer. These include higher health-care costs in general, the increasing costs of innovative treatments, and the increasing cost shifting from payers to patients. These trends heighten the need to develop decision support for patients making decisions about what treatment to receive or even whether and where to receive treatment.

Addressing financial concerns and insurance questions is recognized increasingly as responsibilities of health-care providers. The Institute of Medicine has defined “health-literate” organizations as those who assist patients in navigating, understanding, and using health-care services. One of the attributes of such an organization is that it “communicates clearly what health plans cover and what individuals will have to pay for services.”22 However, although our results underscore that the need is great, many health-care organizations struggle with providing this assistance. A qualitative study of social workers and financial counselors at an academic cancer center noted a lack of financial resources, process insufficiencies, limited resources to screen patients for need, and insurance coverage limitations as major barriers.23 Therefore, research is needed to develop scalable informative programs. Although patient navigation programs have been studied in various settings, focusing specifically on financial concerns through “patient financial navigation” is a nascent endeavor. Health-care systems will need to address these issues to ensure that patients make informed treatment decisions that reflect their preferences and values, including their financial concerns.

In each of our models, older patients were less likely to report financial concerns. This is consistent with a study of Washington State patients with cancer in which those 65 years or older were less likely to file for bankruptcy than were younger patients, suggesting a protective effect from programs such as Medicare and Social Security.24 Consistent coverage policies from payers may also reduce patients’ concerns. Medicare has covered the routine costs associated with clinical trials since 2000. This policy change has been associated with a modest increase in the number of Medicare patients with supplemental insurance enrolling onto Southwest Oncology Group studies.25 However, the overall impact of enrollment of elderly patients onto clinical trials is less clear.26 Medicare policies regarding clinical trial coverage may reduce concerns; it is to be hoped that the minimal coverage standard specified in the Affordable Care Act for commercial insurance carriers will reduce concerns regarding clinical trial coverage among younger patients. Regardless of clinical trial coverage, however, younger patients who are often covered through employer-based insurance are likely concerned about their ability to continue to work and maintain insurance coverage, increasing their financial concerns. The clinical trial of PRE-ACT enrolled a cross section of patients receiving oncology care. We did not find an association between financial concerns and either the presence of metastatic disease or primary tumor sites. This finding is not unexpected, because the issues facing patients with cancer span disease sites and settings.

There were some modest differences among the summary measure (Q1 + Q2 + Q3) and the uncertainty questions (Q2 + Q3) and the burden question (Q1). For example, on multivariable analysis, we did not find an association between burden and self-efficacy. In contrast, the associations between the uncertainty questions (Q2 + Q3) and the psychological constructs did remain. These differences may be a result of the fact that the uncertainty questions (“I'm afraid that my health insurance won't pay for a clinical trial” [Q2] and “I’m worried that I wouldn’t be able to afford the costs of treatment on a clinical trial” [Q3]) raise concerns about future costs, whereas the burden question refers to costs that have already been incurred. However, the overall results were similar and demonstrate that both present and future cost concerns are relevant to a wide range of patients.

Our results should be interpreted within the context of the study’s limitations. We did not collect data regarding patients’ income, insurance status, or medical costs. However, unlike these “hard” end points, financial distress may be more subjective. It has been defined as a reaction, such as mental or physical discomfort, to stress about one’s state of general financial well-being.27 The InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being scale uses questions such as “How often do you worry about being able to meet normal monthly living expenses?” rather than traditional measures of socioeconomic status to assess individuals’ sense of their own financial well-being.28 Patients with financial distress live paycheck-to-paycheck, rather than within the traditional definition of poverty.27 Therefore, subjective questions about financial burden and concerns may be more relevant than objective measures such as income. Furthermore, medical bankruptcies are more likely to occur in patients who are traditionally considered middle class (such as homeowners and those who are college educated).29 That these middle-class families who experienced bankruptcies generally would not be considered “at risk” using traditional measures of socioeconomic status suggests that subjective measures of financial concerns such as the questions asked in PRE-ACT may better identify patients at risk of financial catastrophe.

The constructs measured in PRE-ACT were adapted to clinical trial decision making. It is possible that patients may have had different concerns when making decisions regarding standard treatments. However, the question of financial burden was not specific to clinical trials, and the results were consistent across the models. Although our study included a Web-based tool requiring high-speed Internet, we permitted participation at the study sites to minimize bias associated with computer access. Nevertheless, our patient population was likely younger, better educated, and more affluent than the general population of patients with cancer. In addition, this was a cross-sectional study and it is possible that patients’ responses to these measures may change over time, with further physician interaction.

Our study has several strengths. The large sample was recruited from four centers across the northeast and midwestern United States, showing that our findings were not confined to one center or area of the country. We used validated measures of psychosocial constructs that have been applied to other studies of patients with cancer.20,30,31 Our findings were stable across models that assessed different psychosocial constructs.

In summary, financial concerns may negatively affect informed treatment decision making, such as the decision to participate in a clinical trial. Given the increasing cost of cancer treatments, and the complexity of decisions many patients face, health-care systems will need to provide greater assistance to address patients’ financial concerns to facilitate preference-sensitive treatment decisions.

Supplementary Material

Appendix

Table A1.

Univariate Relationships Between Cost Concerns (Burden and Uncertainty) and Demographics and Psychosocial Measures Scores

| Burden* (Range 1-5) | Uncertainty† (Range 2-10) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | P‡ | Mean (SD) | P§ | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 2.59 (1.12) | .56 | 5.88 (2.17) | .05 |

| Female | 2.65 (1.19) | 6.13 (2.08) | ||

| Age, years | ||||

| ≤ 65 | 2.73 (1.19) | < .001 | 6.14 (2.11) | .002 |

| > 65 | 2.33 (1.00) | 5.71 (2.12) | ||

| Race | ||||

| Nonwhite | 2.75 (1.32) | .29 | 6.12 (2.03) | .56 |

| White | 2.61 (1.14) | 6.01 (2.14) | ||

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 3.17 (1.17) | .01 | 6.82 (2.10) | .07 |

| High school | 2.73 (1.22) | 6.16 (2.09) | ||

| Greater than high school | 2.58 (1.14) | 5.97 (2.13) | ||

| Employment | ||||

| Employed/homemaker/student | 2.64 (1.14) | < .001 | 6.08 (2.15) | .06 |

| Unemployed | 3.08 (1.27) | 6.26 (1.99) | ||

| Retired | 2.38 (1.07) | 5.84 (2.13) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/partnership | 2.57 (1.11) | .02 | 5.96 (2.14) | .08 |

| Not married/partnered | 2.77 (1.27) | 6.21 (2.05) | ||

| Hospital location | ||||

| Pennsylvania | 2.48 (1.13) | < .01 | 5.92 (2.17) | .46 |

| Illinois | 2.44 (1.03) | 5.65 (2.15) | ||

| Michigan | 2.64 (1.17) | 6.06 (1.95) | ||

| Ohio | 2.74 (1.17) | 6.12 (2.15) | ||

| Metastatic disease | ||||

| No | 2.57 (1.17) | .289 | 6.00 (2.02) | .98 |

| Yes | 2.64 (1.14) | 6.00 (2.11) | ||

| Primary site | ||||

| Breast | 2.56 (1.20) | .48 | 6.07 (2.28) | .75 |

| Colorectal | 2.73 (1.09) | 5.93 (2.01) | ||

| Lung | 2.68 (1.22) | 6.13 (1.99) | ||

| Pancreatic | 2.69 (1.12) | 5.77 (2.13) | ||

| Prostate | 2.48 (1.03) | 5.83 (2.25) | ||

| Other | 2.64 (1.16) | 6.06 (2.07) | ||

| Self-efficacy, quartile | ||||

| 1st | 2.71 (1.17) | .32 | 6.39 (1.94) | < .001 |

| 2nd | 2.60 (1.16) | 6.17 (2.01) | ||

| 3rd | 2.53 (1.12) | 5.86 (2.27) | ||

| 4th | 2.60 (1.16) | 5.75 (2.21) | ||

| Preparation, quartile | ||||

| 1st | 2.73 (1.18) | .07 | 6.66 (1.85) | < .001 |

| 2nd | 2.64 (1.13) | 6.16 (2.12) | ||

| 3rd | 2.48 (1.13) | 5.79 (2.13) | ||

| 4th | 2.57 (1.19) | 5.37 (2.19) | ||

| Distress, quartile | ||||

| 1st | 2.54 (1.14) | < .001 | 5.65 (2.13) | < .001 |

| 2nd | 2.44 (1.11) | 5.86 (2.18) | ||

| 3rd | 2.61 (1.12) | 5.94 (2.01) | ||

| 4th | 2.89 (1.22) | 6.65 (2.03) | ||

| Decisional conflict, quartile | ||||

| 1st | 2.55 (1.16) | .24 | 5.53 (2.21) | < .001 |

| 2nd | 2.51 (1.22) | 6.12 (2.14) | ||

| 3rd | 2.53 (1.08) | 6.09 (2.00) | ||

| 4th | 2.75 (1.22) | 6.47 (2.12) | ||

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Burden (Q1): Q1 “How much of a burden on you is the cost of your medical care?

Uncertainty (Q2 + Q3): Q2: “I'm afraid that my health insurance won't pay for a clinical trial” + Q3: “I’m worried that I wouldn’t be able to afford the costs of treatment on a clinical trial.

P value from one-way analysis of variance.

P value from Kruskal-Wallis test.

Table A2.

Multivariable Analyses, by Psychosocial Construct, Burden Question (Q1)

| Self-Efficacy | Preparation | Distress | Decisional Conflict | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate (95% CI) | P | Estimate (95% CI) | P | Estimate (95% CI) | P | Estimate (95% CI) | P |

| Self-efficacy | 0.00 (−0.01 to 0.00) | .25 | −0.01 (−0.01 to 0.00) | .01 | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.01) | < .001 | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.01) | .02 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 0.01 (−0.12 to 0.14) | .89 | 0.01 (−0.13 to 0.14) | .93 | −0.04 (−0.18 to 0.09) | .54 | 0.06 (−0.12 to 0.23) | .53 |

| Male | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Race | ||||||||

| Nonwhite | 0.07 (−0.13 to 0.28) | .48 | 0.05 (−0.15 to 0.26) | .63 | 0.09 (−0.11 to 0.30) | .38 | 0.00 (−0.27 to 0.27) | .99 |

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Education | ||||||||

| More than high school | −0.42 (−0.86 to 0.01) | .06 | −0.43 (−0.86 to 0.00) | .05 | −0.45 (−0.90 to 0.00) | .05 | −0.19 (−0.83 to 0.44) | .55 |

| High school | −0.31 (−0.76 to 0.13) | .17 | −0.32 (−0.76 to 0.12) | .15 | −0.36 (−0.82 to 0.11) | .13 | −0.23 (−0.88 to 0.42) | .48 |

| Less than high school | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Employment | ||||||||

| Retired | −0.14 (−0.33 to 0.04) | .12 | −0.15 (−0.33 to 0.03) | .10 | −0.15 (−0.33 to 0.03) | .11 | −0.20 (−0.43 to 0.03) | .09 |

| Unemployed | 0.37 (0.18 to 0.56) | < .001 | 0.40 (0.21 to 0.59) | < .001 | 0.35 (0.16 to 0.54) | <.001 | 0.28 (0.02 to 0.54) | .03 |

| Used/homemaker/student | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Age, years | ||||||||

| > 65 | −0.27 (−0.45 to −0.08) | < .01 | −0.28 (−0.46 to −0.09) | .003 | −0.25 (−0.44 to −0.06) | .009 | −0.33 (−0.57 to −0.09) | .006 |

| ≤ 65 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married/partnership | −0.12 (−0.27 to 0.04) | .13 | −0.12 (−0.27 to 0.03) | .12 | −0.11 (−0.26 to 0.04) | .14 | −0.08 (−0.29 to 0.12) | .41 |

| Not married/partnered | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Hospital location | ||||||||

| Illinois | −0.07 (−0.63 to 0.49) | .81 | −0.09 (−0.65 to 0.48) | .77 | −0.01 (−0.57 to 0.55) | .97 | −0.37 (−1.22 to 0.49) | .40 |

| Michigan | 0.18 (−0.02 to 0.37) | .07 | 0.16 (−0.04 to 0.35) | .11 | 0.16 (−0.04 to 0.35) | .11 | 0.24 (−0.01 to 0.48) | .06 |

| Ohio | 0.29 (0.15 to 0.44) | < .001 | 0.29 (0.15 to 0.43) | < .001 | 0.30 (0.16 to 0.45) | <.001 | 0.32 (0.13 to 0.51) | <.001 |

| Pennsylvania | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Study arm | ||||||||

| Control | 0.18 (0.01 to 0.35) | .03 | ||||||

| PRE-ACT | Ref | |||||||

Abbreviations: PRE-ACT, Preparatory Education About Clinical Trials; Ref, reference.

Table A3.

Multivariable Analyses, by Psychosocial Construct, Uncertainty Questions (Q2+Q3)

| Self-Efficacy | Preparation | Distress | Decisional Conflict | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (95% CI) | P | Estimate (95% CI) | P | Estimate (95% CI) | P | Estimate (95% CI) | P | |

| Psychosocial construct | −0.02 (−0.03 to −0.01) | < .001 | −0.03 (-0.04 to -0.03) | < .001 | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.03) | <.001 | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.03) | < .001 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 0.21 (−0.04 to 0.46) | .10 | 0.25 (0.00 to 0.49) | .05 | 0.09 (-0.16 to 0.35) | .46 | 0.16 (−0.17 to 0.49) | .34 |

| Male | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Race | ||||||||

| Nonwhite | 0.02 (−0.37 to 0.40) | .93 | 0.01 (−0.37 to 0.39) | .95 | 0.00 (−0.39 to 0.39) | 1.00 | −0.34 (−0.85 to 0.17) | .19 |

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Education | ||||||||

| More than high school | −0.78 (−1.59 to 0.03) | .06 | −0.80 (−1.59 to 0.00) | .05 | −0.61 (−1.45 to 0.22) | .15 | −0.53 (−1.72 to 0.65) | .38 |

| High school | −0.61 (−1.45 to 0.22) | .15 | −0.67 (−1.48 to 0.15) | .11 | −0.44 (−1.31 to 0.42) | .31 | −0.52 (−1.73 to 0.69) | .40 |

| Less than high school | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Employment | ||||||||

| Retired | 0.07 (−0.27 to 0.41) | .66 | 0.03 (−0.30 to 0.36) | .84 | −0.01 (−0.35 to 0.33) | .95 | 0.06 (−0.37 to 0.49) | .79 |

| Unemployed | 0.15 (−0.21 to 0.51) | .41 | 0.16 (−0.19 to 0.51) | .36 | 0.06 (−0.30 to 0.42) | .74 | 0.14 (−0.34 to 0.62) | .57 |

| Employed/homemaker/student | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Age, years | ||||||||

| > 65 | −0.41 (−0.76 to −0.07) | .02 | −0.48 (−0.82 to −0.15) | .005 | −0.32 (−0.67 to 0.03) | .07 | −0.63 (−1.07 to −0.18) | < .01 |

| ≤ 65 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married/partnership | −0.17 (−0.46 to 0.11) | .22 | −0.20 (−0.47 to 0.08) | .16 | −0.21 (−0.49 to 0.07) | .14 | −0.04 (−0.42 to 0.34) | .83 |

| Not married/partnered | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Hospital location | ||||||||

| Illinois | −0.30 (−1.32 to 0.72) | .56 | −0.32 (−1.32 to 0.67) | .52 | −0.16 (−1.17 to 0.86) | .76 | −0.17 (−1.66 to 1.32) | .82 |

| Michigan | 0.17 (−0.19 to 0.53) | .36 | 0.09 (−0.27 to 0.44) | .63 | 0.11 (−0.25 to 0.47) | .55 | 0.01 (−0.45 to 0.46) | .98 |

| Ohio | 0.16 (−0.11 to 0.43) | .24 | 0.13 (−0.13 to 0.39) | .32 | 0.23 (−0.04 to 0.49) | .09 | 0.08 (−0.27 to 0.44) | .65 |

| Pennsylvania | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Study arm | ||||||||

| Control | 0.01 (−0.30 to 0.32) | .95 | ||||||

| PRE-ACT | Ref | |||||||

Abbreviations: PRE-ACT, Preparatory Education About Clinical Trials; Ref, reference.

Table A4.

Multivariable Analyses of Decisional Conflict, Using Post-Intervention Uncertainty Questions (Q2 + Q3)

| Estimate (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Decisional conflict | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.03) | < .001 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 0.24 (−0.11 to 0.59) | .1839 |

| Male | Ref | |

| Race | ||

| Nonwhite | −0.27 (−0.27 to 0.26) | .317 |

| White | Ref | |

| Education | ||

| More than high school | 0.17 (−1.08 to 1.41) | .7926 |

| High school | 0.23 (1.04 to 1.51) | .7193 |

| Less than high school | Ref | |

| Employment | ||

| Retired | 0.03 (−0.43 to 0.48) | .9032 |

| Unemployed | 0.10 (−0.40 to 0.61) | .6876 |

| Employed/homemaker/student | Ref | |

| Age, years | ||

| > 65 | −0.61(−1.08 to −0.14) | .0105 |

| ≤ 65 | Ref | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/partnership | 0.19 (−0.22 to 0.59) | .3641 |

| Not married/partnered | Ref | |

| Hospital location | ||

| Illinois | 0.23 (−1.33 to 1.80) | .7694 |

| Michigan | 0.12 (−0.36 to 0.60) | .6172 |

| Ohio | 0.13 (−0.25 to 0.50) | .5054 |

| Pennsylvania | Ref | |

| Study arm | ||

| Control | 0.48 (0.15 to 0.80) | .0041 |

| PRE-ACT | Ref |

Abbreviations: PRE-ACT, Preparatory Education About Clinical Trials; Ref, reference.

Table A5.

Univariate Relationships between Psychosocial Constructs and Demographics and Summary Cost Concerns

| Parameter | Self-Efficacy Mean (SD) | P* | Preparation Mean (SD) | P† | Distress Mean (SD) | P† | Decisional Conflict Mean (SD) | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 84.98 (15.66) | .3257 | 71.88 (16.21) | .0996 | 24.89 (15.75) | < .001 | 24.33 (17.04) | .001 |

| Female | 83.9 (16.37) | 73.36 (14.96) | 31.44 (14.82) | 20.17 (17.81) | ||||

| Age, years | ||||||||

| ≤ 65 | 83.84 (16.22) | .0506 | 73.45 (14.97) | .0089 | 30.07 (15.45) | < .001 | 20.96 (17.56) | .0079 |

| > 65 | 85.74 (15.63) | 70.84 (16.73) | 25.10 (15.21) | 24.5 (17.52) | ||||

| Race | ||||||||

| Nonwhite | 86.9 (15.73) | .0162 | 73.95 (16.38) | .3198 | 27.59 (16.27) | .3598 | 24.8 (17.37) | .0927 |

| White | 83.98 (16.1) | 72.57 (15.39) | 28.88 (15.45) | 21.49 (17.62) | ||||

| Education | ||||||||

| Less than high school | 85.19 (15.05) | .9429 | 72.68 (20.17) | .0472 | 31.40 (20.47) | .4253 | 32.69 (19.37) | .065 |

| High school | 82.98 (18.78) | 70.65 (15.78) | 29.54 (16.59) | 22.88 (17.51) | ||||

| More than high school | 84.68 (15.3) | 73.33 (15.24) | 28.45 (15.10) | 21.37 (17.55) | ||||

| Employment | ||||||||

| Employed/homemaker/student | 83.06 (17.02) | .0262 | 73.10 (15.11) | .1342 | 29.24 (15.35) | < .001 | 20.91 (18.06) | .1655 |

| Unemployed | 84.83 (15.66) | 74.05 (14.81) | 32.86 (14.53) | 23.82 (16.08) | ||||

| Retired | 86.26 (14.47) | 71.55 (16.41) | 25.96 (15.84) | 22.6 (17.44) | ||||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married/partnered | 84.51 (15.74) | .8822 | 72.66 (15.33) | .7124 | 28.60 (15.42) | .6449 | 20.64 (17.53) | .001 |

| Not married/partnered | 83.91 (17.05) | 73.03 (16.01) | 29.07 (15.83) | 25.8 (17.32) | ||||

| Hospital location | ||||||||

| Pennsylvania | 84.92 (15.61) | .1005 | 74.35 (14.33) | .0449 | 29.74 (14.84) | .0344 | 21.74 (18.45) | .4127 |

| Illinois | 83.96 (16.16) | 73.38 (15.71) | 24.00 (16.97) | 21.68 (21.75) | ||||

| Michigan | 86.89 (13.6) | 72.04 (16.57) | 30.29 (16.45) | 23.46 (16.31) | ||||

| Ohio | 82.99 (17.13) | 71.66 (15.96) | 27.54 (15.64) | 21.26 (17.46) | ||||

| Cost concerns, quartile | ||||||||

| 1st | 88.59 (13.38) | < .001 | 79.18 (13.97) | < .001 | 24.77 (14.68) | < .001 | 17.32 (16.13) | .001 |

| 2nd | 84.77 (15.08) | 73.46 (14.44) | 27.67 (15.10) | 20.46 (16.31) | ||||

| 3rd | 83.53 (16.12) | 70.54 (16.15) | 29.29 (15.35) | 24.11 (17.61) | ||||

| 4th | 81.66 (18.13) | 70.20 (14.82) | 32.69 (15.91) | 24.57 (19.25) |

P value from Kruskal-Wallis test.

P value from one-way analysis of variance.

Footnotes

See accompanying article on page 469

Deceased.

Supported by R01 CA127655, P30 CA06927, and P30 CA43703 from the National Institutes of Health.

Presented in part at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Medical Decision Making, October 23, 2013, Baltimore, MD, and the 49th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, May 31, 2013, Chicago, IL.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information: NCT00750009.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Yu-Ning Wong, Joanne Buzaglo, Michael Collins, Linda Fleisher, Michael Katz, Sharon Manne, Suzanne M. Miller, Stephanie Raivitch, Nancy Roach, Neal J. Meropol

Financial support: Neal J. Meropol

Administrative support: Tyler G. Kinzy, Tasnuva M. Liu, Neal J. Meropol

Provision of study materials or patients: Al Bowen Benson III, Neal J. Meropol

Collection and assembly of data: Yu-Ning Wong, Terrance L. Albrecht, Anne Lederman Flamm, Suzanne M. Miller, Tyler G. Kinzy, Tasnuva M. Liu, Dawn M. Miller, David Poole, Eric Ross, Neal J. Meropol

Data analysis and interpretation: Yu-Ning Wong, Mark D. Schluchter, Al Bowen Benson III, Sharon Manne, Suzanne M. Miller, Seunghee Margevicius, Eric Ross, Neal J. Meropol

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Financial Concerns About Participation In Clinical Trials Among Patients With Cancer

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Yu-Ning Wong

Research Funding: Pfizer, Bayer Health Care Pharmaceuticals

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Tokai Pharmaceuticals

Mark D. Schluchter

No relationship to disclose

Terrance L. Albrecht

Consulting or Advisory Role: Eli Lilly

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Eli Lilly

Al Bowen Benson III

Consulting or Advisory Role: Opsona Therapeutics, Bayer, Genentech, Sanofi, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Serono, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Lilly/ImClone, Genomic Health, Vicus Therapeutics, Pharmacyclics, Precision Therapeutics, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Boston Biomedical

Research Funding: Taiho Pharmaceutical, Genentech, Amgen, Gilead Sciences, Astellas Pharma, AVEO Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Advanced Accelerator Applications, Bayer, MSD Oncology, MedImmune, Merck Sharp & Dohme

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Genentech, Celgene, Bayer, Lilly/ImClone, Boston Biomedical, Opsona Therapeutics

Joanne Buzaglo

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Genentech, Janssen Biotech, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Amgen, Pfizer Oncology, Pharmacyclics, Eli Lilly, Bayer, Helsinn Therapeutics

Michael Collins

Employment: Infinity HealthCare

Stock or Other Ownership: Infinity HealthCare

Anne Lederman Flamm

Leadership: Precision Image Analysis

Stock or Other Ownership: Renova Therapeutics, CryoThermics, nVision

Research Funding: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals

Linda Fleisher

No relationship to disclose

Michael Katz

No relationship to disclose

Tyler G. Kinzy

No relationship to disclose

Tasnuva M. Liu

No relationship to disclose

Sharon Manne

No relationship to disclose

Seunghee Margevicius

No relationship to disclose

Dawn M. Miller

No relationship to disclose

Suzanne M. Miller

No relationship to disclose

David Poole

No relationship to disclose

Stephanie Raivitch

No relationship to disclose

Nancy Roach

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Taiho Pharmaceutical

Eric Ross

Stock or Other Ownership: Proctor & Gamble

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Method for screening muscle invasive bladder cancer patients for neoadjuvant chemotherapy responsiveness

Neal J. Meropol

Consulting or Advisory Role: BioMotiv

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: US Patent 20020031515

REFERENCES

- 1.Manne S, Kashy D, Albrecht T, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy as predictors of preparedness for oncology clinical trials: A mediational model. Med Decis Making. 2014;34:454–463. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13511704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller SM, Hudson SV, Egleston BL, et al. The relationships among knowledge, self-efficacy, preparedness, decisional conflict, and decisions to participate in a cancer clinical trial. Psychooncology. 2013;22:481–489. doi: 10.1002/pon.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al. International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: Online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333:417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38926.629329.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett C, Graham ID, Kristjansson E, et al. Validation of a preparation for decision making scale. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:130–133. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knops AM, Goossens A, Ubbink DT, et al. Interpreting patient decisional conflict scores: behavior and emotions in decisions about treatment. Med Decis Making. 2013;33:78–84. doi: 10.1177/0272989X12453500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Connor AM. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making. 1995;15:25–30. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nielsen BK, Mehlsen M, Jensen AB, et al. Cancer-related self-efficacy following a consultation with an oncologist. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2095–2101. doi: 10.1002/pon.3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlson LE, Waller A, Mitchell AJ. Screening for distress and unmet needs in patients with cancer: Review and recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1160–1177. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: The cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3868–3874. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schrag D, Hanger M. Medical oncologists’ views on communicating with patients about chemotherapy costs: A pilot survey. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:233–237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McFarlane J, Riggins J, Smith TJ. SPIKE$: A six-step protocol for delivering bad news about the cost of medical care. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4200–4204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bullock AJ, Hofstatter EW, Yushak ML, et al. Understanding patients’ attitudes toward communication about the cost of cancer care. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:e50–e58. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernard DSM, Farr SL, Fang Z. National estimates of out-of-pocket health care expenditure burdens among nonelderly adults with cancer: 2001 to 2008. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2821–2826. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stump TK, Eghan N, Egleston BL, et al. Cost concerns of patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:251–257. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.000929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleisher L, Ruggieri DG, Miller SM, et al. Application of best practice approaches for designing decision support tools: The preparatory education about clinical trials (PRE-ACT) study. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meropol NJ, Albrecht TL, Wong Y-N, et al. Randomized trial of a web-based intervention to address barriers to clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:469–478. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Connor A. User Manual: Decision Self-Efficacy Scale. 2002 http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_Decision_SelfEfficacy.pdf.

- 20.Stacey D, O’Connor AM, DeGrasse C, et al. Development and evaluation of a breast cancer prevention decision aid for higher-risk women. Health Expect. 2003;6:3–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2003.00195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brach C, Dreyer B, Schyve P, et al. Attributes of a Health Literate Organization. Washington, DC, Institute of Medicine; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith SK, Nicolla J, Zafar SY. Bridging the gap between financial distress and available resources for patients with cancer: A qualitative study. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:e368–e372. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington state cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff. 2013;32:1143–1152. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unger JM, Coltman CA, Jr, Crowley JJ, et al. Impact of the year 2000 Medicare policy change on older patient enrollment to cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:141–144. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gross CP, Wong N, Dubin JA, et al. Enrollment of older persons in cancer trials after the Medicare reimbursement policy change. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1514–1520. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.13.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Neill B, Sorhaindo B, Prawitz AD, et al. Financial distress: definition, effects, and measurement. Consumer Interests Annual. 2006;52:489–496. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prawitz AD, Thomas Garman E, Sorhaindo B, et al. InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale: Development, administration, and score interpretation. Financ Couns Plan. 2006;17:34–50. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Himmelstein DU, Thorne D, Warren E, et al. Medical bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: results of a national study. Am J Med. 2009;122:741–746. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manne SL, Meropol NJ, Weinberg DS, et al. Facilitating informed decisions regarding microsatellite instability testing among high-risk individuals diagnosed with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1366–1372. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Metcalfe KA, Quan M-L, Eisen A, et al. The impact of having a sister diagnosed with breast cancer on cancer-related distress and breast cancer risk perception. Cancer. 2013;119:1722–1728. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.