Abstract

During translation initiation, eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2) delivers the Met-tRNA to the 40S ribosomal subunit to locate the initiation codon (AUGi) of mRNA during the scanning process. Stress-induced eIF2 phosphorylation leads to a general blockade of translation initiation and represents a key antiviral pathway in mammals. However, some viral mRNAs can initiate translation in the presence of phosphorylated eIF2 via stable RNA stem-loop structures (DLP; Downstream LooP) located in their coding sequence (CDS), which promote 43S preinitiation complex stalling on the initiation codon. We show here that during the scanning process, DLPs of Alphavirus mRNA become trapped in ES6S region (680–914 nt) of 18S rRNA that are projected from the solvent side of 40S subunit. This trapping can lock the progress of the 40S subunit on the mRNA in a way that places the upstream initiator AUGi on the P site of 40S subunit, obviating the participation of eIF2. Notably, the DLP structure is released from 18S rRNA upon 60S ribosomal subunit joining, suggesting conformational changes in ES6Ss during the initiation process. These novel findings illustrate how viral mRNA is threaded into the 40S subunit during the scanning process, exploiting the topology of the 40S subunit solvent side to enhance its translation in vertebrate hosts.

INTRODUCTION

RNA structure represents a layer of gene regulation whose implications are now beginning to be understood (1). Regions in RNA strands can fold spontaneously into stem-loops (SLs) of diverse length and topology that are stabilized mainly by Watson–Crick base pairing, although other hydrogen bonds involving G–U and C–A pairs are possible (2–5). Although in most cases the mere presence of SLs in RNA provides no clues about their function, there are many examples of their functional diversity. Accordingly, SLs can be directly involved in decoding (e.g. tRNAs), in catalysis (e.g. ribozymes), in scaffolding (e.g. rRNA), in alternative splicing or in promoting the binding of mRNA to the ribosomes (5). Structures found in the non-coding regions of mRNA can positively or negatively affect translation. For example, extensive secondary structure in the 5′UTR of many cellular mRNAs decreases translation efficiency by hindering the scanning by the preinitiation complex (43S) necessary to locate the initiation codon in most mRNAs (6–9). In some viral mRNAs, however, the presence of special elements of secondary/tertiary structure (IRES; Internal Ribosome Entry Site) in the 5′UTR promotes the direct recruitment of the 43S complex to initiate translation (10,11). Given the limited unwinding activity of the 43S complex, translation of most mRNAs requires the participation of RNA helicases, which convert the incoming RNA into a single-strand for proper codon inspection. Eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF) 4A (eIF4A) is the canonical RNA helicase that associates with eIF4E and eIF4G to bind near the 5′extreme of mRNA, promoting 43S complex loading and subsequent scanning (11,12). It is thought that eIF4A (as part of the eIF4F complex) promotes the unidirectional (toward 3′) scanning of the 43S complex by alternating cycles of mRNA binding and strand separation in an ATP-dependent manner (12–14). Nonetheless, the 43S complex can bypass SLs of moderate stability without unwinding under some circumstances (15,16), although it is generally accepted that an increase in the secondary structure of the 5′UTR makes the mRNA more dependent on eIF4A activity (8). Recently, other proteins with helicase-like activities, such as DHX29 or DDX3, have been shown to promote the entry of mRNA into the mRNA binding cleft of the 40S subunit by a still poorly understood mechanism (12,17,18).

Very few examples of translation regulation by RNA structures in the CDS have been reported. In some viral mRNAs, the presence of pseudo-knot structures can promote a frame-shift during translation elongation, allowing the synthesis of a protein with an extended C-terminus (19). Another example of SL-mediated translation control operates in the coding region of subgenomic mRNA of Alphavirus. To counteract the activation of host protein kinase R (PKR), which leads to phosphorylation of eIF2 in cultured cells and in animals infected with these viruses, subgenomic mRNAs of Sindbis virus (SV) and other Alphaviruses are endowed with a stable stem-loop structure called the downstream-loop (DLP). The DLP is located 27–31 nt downstream of the AUGi and promotes efficient translation of subgenomic mRNA in the presence of phosphorylated eIF2 (20–22). The DLP was initially identified as a translation enhancer in SV, able to increase translation of a heterologous mRNA up to 10-fold in virus-infected cells (22,23); although more recently, it has been proposed that eIF2A or eIF2D might deliver the Met-tRNAi to the initiation complex under eIF2 phosphorylation (20,24). The presence of the DLP in SV mRNA has been interpreted as an adaptation for replication in vertebrates since this structure is not essential for viral replication in insects (25). The DLP structure is believed to allow the location of AUGi by slowing down the scanning of 43S complex on this mRNA, although the mechanism has not been described to date. This has been due in part to our still limited knowledge of how mRNA enters the ribosome channel during scanning, a process that is presumably influenced by the topology of the solvent side of 43S complex. Thus, the exact position of eIF4F in the 43S-mRNA complex and how eIF4A helicase works during the scanning are still matters of debate (11,26). Based on structural and functional data, we show here new insights into the scanning process, describing how a SL in the proximal region of viral mRNA can promote an eIF2-less translation initiation by trapping in RNA extensions of the 40S subunit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA cloning

The accession numbers for the Alphavirus genomes used in this study are the following: Sindbis virus (SV; NC_001547.1), Aura virus (AURAV; AF126284), Chikungunya virus (CHIKV; NC_004162), O′nyong′nyong virus (ONNV; NC_001512), eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV(SA); AF159559 and EEEV (NA); U01558), Mayaro virus (MAYV; DQ001069), Semliki Forest virus (SFV; NC_003215), Ross River virus (RRV; DQ226993 and RRV (Sagiyama); AB032553), Getah virus (GETV; NC_006558), Middelburg virus (MIDV;EF536323), Una virus (UNAV; AF33948) and Bebaru virus (BEBV; AF339480). The sequences corresponding to the first 80–200 nt of the CDS of 26S mRNAs (depending on the virus) were amplified by PCR using a primer pair with overlapping 3′ends, except in the case for AURAV where the sequence corresponding to the DLP was amplified from genomic RNA. PCR products were cloned in-frame with EGFP in a vector using XbaI and NotI enzymes. A second PCR amplification using 5′L 26S forward (20) and 3′ EGFP-ApaI primers was carried out and the products were cloned into the plasmid pTE/5′2J using XbaI and ApaI enzymes (Supplementary Table S1). Plasmid pTE/5′2J is an infectious clone of SV with a duplicated subgenomic promotor to express cloned products (27). To change the distance (d) in SV-DLP enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), we inserted or deleted triplets in the AUG–DLP stretch using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the appropriate primers (the corresponding forward primer and the reverse 3′ EGFP-ApaI). The products were digested with XbaI and ApaI and cloned into pTE /5′2J. To introduce SLs into the 5′ UTR of SV-DLP EGFP, we used a XbaI site to insert linkers containing SLs prepared by annealing primer pairs with overlapping 3′ends (SL-30 and Flat), or by PCR amplification of a designed primer template containing the SL flanked by XbaI sites (SL-50). All constructs were verified by sequencing.

Recombinant virus preparation and infection

pTE/5′2J-EGFP plasmids were linearized with XhoI and in vitro transcribed with SP6 RNA polymerase (NEB) in the presence of cap analog (7methyl-GTP, Promega). Approximately 3 μg of in vitro synthesized SV RNA was electroporated into ∼107 BHK21 cells and virus was recovered after the cytopathic effect was complete. Recombinant viruses were further amplified in BHK21 cells (3 × 107) and purified on a sucrose cushion as described (21). The resulting viral preparations (108–109 pfu/ml) were highly homogeneous with >90% of viruses expressing EGFP as judged by microscopy analysis of BHK21 cells infected at low multiplicity of infection (moi). For virus infections, mouse 3T3 cells derived from wild-type (WT) and PKRo/o animals, and C6/36 cells derived from Aedes albopictus were used as described (25). Cells were infected with the indicated virus at a moi of 25 pfu/cell in 24-well plates and analyzed by live cell fluorescence microscopy at 5–6 h post-infection (hpi). Extracts from infected cells were also prepared at this time for Western blotting as described previously (21).

Transfection of oligonucleotides

Cells were grown in 24-well plates at 60–70% confluency and then transfected with 100 pmol of oligonucleotide using Lipotransfectin (NiborLab). Oligonucleotide uptake was monitored using a fluorescence microscope. At 12 h post-transfection, cells were infected with SFV and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy (21) or metabolically labeled with [35S]-Met/Cys and analyzed as described (20).

Probing and modeling RNA structures

To synthesize RNAs for structural probing (SHAPE; selective 2′-hydroxyl acylation and primer extension), the corresponding viral DNA sequences were amplified by PCR using T7-5′ XbaI and DLP′s-3′primers to generate templates for transcription (Supplementary Table S1). Approximately 2 μg of DNA template was transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase (Promega) for 90 min at 37°C using 0.5 mM of each NTP, digested with DNAse RQ1 (Promega) and RNAs were purified through Chromaspin-30 columns (Clontech). Approximately 5 pmol of RNA was treated with 5–16 mM N-methylisatoic anhydride (NMIA; Invitrogen) for 45 min at 37°C, precipitated with isopropanol and retrotranscribed with Superscript III (Invitrogen) using 5′-labeled [γ−32P] DLP′s-3′ primer. In parallel, RNA was retrotranscribed with 1 mM ddNTPs/1 mM dNTPs for sequencing. Fragments were analyzed in 10% acrylamide-urea gels (28) or by capillary electrophoresis (20). Bands were quantified by densitometry and normalized. SHAPE data were used as constraints to generate 2D and 3D models using the MC-fold and RNAComposer pipelines (29,30). RNAfold (Vienna RNA Web Services) was routinely used to calculate the minimal folding energy of centroid RNA structures and base pair probabilities.

Western blotting and immunofluorescence

Western blotting was carried out as described (20) using the following primary antibodies: α-EGFP (Clontech), α-SV E1, α-SV C (21) and α-eIF2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immunoreactivity was revealed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, GE) and bands were quantified by densitometry. For immunofluorescence (IF) analysis, cells were grown on coverslips, fixed with 4% PFA for 20 min at room temperature (RT), treated with 50 mM NH4Cl, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 buffer, blocked in 5% BSA and incubated overnight at 4°C with the SFV-C antibody (1:500) in a wet chamber. Coverslips were then incubated with a secondary antibody coupled to fluorescein (green) for 2 h at RT, washed with PBS-0.1% Triton X-100, stained with DAPI and mounted. Slides were examined and photographed in a Leica confocal microscope.

UV crosslinking experiments

To synthesize photoactivatable RNA for UV crosslinking, we first designed primers to prepare DNA templates with T residues in the desired positions (Supplementary Table S1). Transcription with T7 RNA polymerase was carried out with 0.45 mM 4-thio UTP (Jena Bioscience) and 0.05 mM UTP. The transcription mixture also included 30 μCi [α−32P]-GTP and 12 μM GTP. Reactions were incubated for 3 h at 37°C and RNA was recovered by filtration through Chromaspin-30 columns (Clontech). mRNAs (∼106 cpm) were assembled in 48S or 80S complexes in 50–100 μl of rabbit reticulocyte mixtures (RRL, Promega) for 20 min at 30°C with 100 μM GMP-PNP or 5 mM cycloheximide (CHX), respectively. All translation mixtures contained a 70% volume of RRL and 10 μM of aminoacids. Samples were irradiated on ice for 20 min with a 360 nm lamp (2 × 6W) at a distance of 2.5–3 cm. The lysates were then diluted in 1 ml of cold polysome buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM DTT) and centrifuged at 90 000 xg for 3 h on a 20% sucrose cushion prepared in polysome buffer. Ribosomal pellets were rinsed briefly with polysome buffer, resuspended in 50 μl of TE + 1% SDS, digested with proteinase K, extracted with phenol and ethanol precipitated. RNA was dissolved in denaturing buffer containing 70% formamide, heated at 70°C for 10 min and analyzed by denaturing agarose gel (formaldehyde) electrophoresis followed by blotting to a nylon membrane.

Identification of contacts with 18S rRNA

To map the region of 18S rRNA that contacted with mRNA, we first used RNase H mapping as described previously (31). UV crosslinking experiments were carried out as described above and the resulting [α−32P]-labeled RNA samples were annealed with 10 pmol of oligonucleotides covering different regions of 18S rRNA. Samples were then digested with 5 U of RNase H (NEB) for 15 min at 37°C and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis as before. To identify the contacts of viral mRNA with 18S rRNA, initiation complexes were assembled as described above except that an unlabeled version of mRNAs containing a poly(A) tail of 35 nt was used. The complexes were crosslinked, centrifuged at high speed and ribosomal pellets were resuspended in cracking buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.5 M LiCl, 0.5% LiDS, 1 mM EDTA and 5 mM DTT). mRNA poly(A)+ was bound to oligo (dT)25 magnetic beads (NEB) at RT for 20 min. Beads were extensively washed according to the manufacturer's recommendations and eluted in TE buffer by heating the samples at 60°C for 10 min. RNA was extracted with phenol, precipitated with ethanol and resuspended in 15 μl of TE buffer. Crosslinking sites in 18S rRNA were identified by primer extension arrest using 5′-[α −32P] primers 4 and 5.1 as described above (see also Supplementary Figure S5).

Modeling of 48S and 80S initiation complexes

To compare 43S and 80S complexes, we used the available crystal structure of rabbit 40S subunit (PDB: 4KZZ) and cryo-electron microscopy reconstructions of rabbit 43S complex (EMD-5658) and 80S complex (rabbit: EMD-5326, human: EMD-5592 and fly: EMD-5591) (32–34). Because information for ES6S helix B is lacking in 40S subunit crystal (PDB: 4KZZ), we used the corresponding EM density map (EMD-5658) to model the arrangement of ES6SB in the 40S subunit crystal. To model SV mRNA embedded in the 40S subunit channel, we assumed an average rise per base of 4.5 Å for a ssRNA molecule based on published data (32). To analyze the changes in ES6S conformation between rabbit 48S and 80S complexes, we compared 43S (EMD-5658) and 80S (EMD-5326) EM maps. We first placed them into the box of the same size (2343) and filtered them to the same resolution (11.6 Å), using EMAN1.4 work package (35). Both volumes were normalized using the Xmipp package (36). The relative position of EMD-5658 to EMD-5326 was assessed by fitting the 40S subunit part of the EMD-5658 cryo-EM map within the EMD-5326 map using UCSF Chimera program (37). Both EM maps were visualized and colored using UCSF Chimera.

Other bioinformatic and statistical analysis

To fold the first 200 nt of CDS mRNAs from mouse and human, we extracted the complete set of mRNA sequences from ENSEMBL (release 75) to send to the RNAfold programme under local configuration. Principal component and correlation analysis as well as tests for significance were performed with the JMP9 (SAS) and Prism 6 (GraphPad software) programs.

RESULTS

Structure of alphaviral DLPs

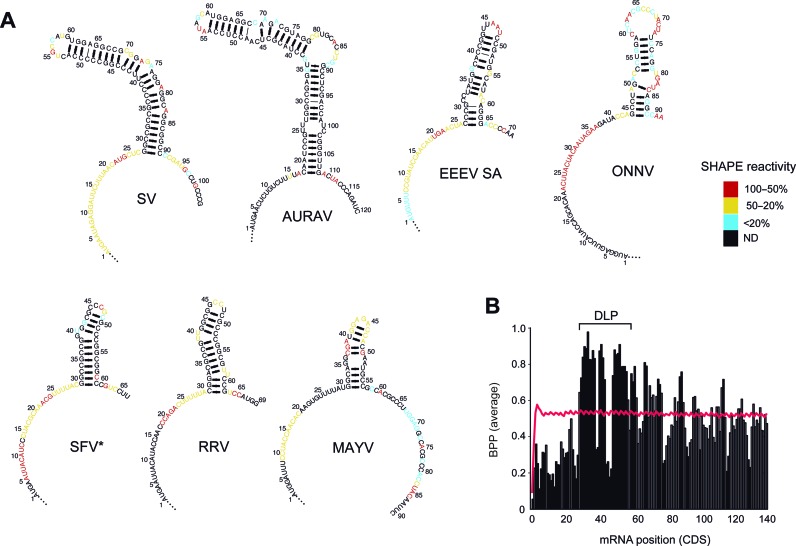

The DLP structure has been previously characterized in SV 26S mRNA and also detected in SFV (22,25). To test whether DLP structures are also present in other members of the Alphavirus genus and to define the elements in these structures important for translation activity, we performed a comparative analysis among Alphavirus genomes. We cloned the first 80–200 nt of the CDS of 26S mRNA from 14 Alphaviruses, including New World (MAYV, UNAV, EEEV (NA), EEEV (SA), AURAV) and Old World (SV, SFV, BEBV, RRV, SAG, GETV, MIDV, CHIKV, ONNV) members. The corresponding RNAs were in vitro synthesized, folded and subjected to structural probing by SHAPE (28). Using SHAPE data as constraints, we generated highly confident 2D and 3D models of DLP structures through the MC-Fold and RNAComposer pipelines (29,30). Stable stem-loop structures were detected in all cases except for CHIKV and ONNV, whereas MAYV and EEEV showed DLPs of lower stability (Figure 1A). Two main topologies were detected: a compact and stable structure in the SFV clade, and a more extended structure in the SV group. In both cases, DLP structures were preceded by a region of intense SHAPE reactivity, suggesting a single stranded conformation for the AUG-DLP stretch. Accordingly, this region showed a high content of A and a low content of G that resulted in a low propensity to form secondary structures when compared with equivalent positions in whole mouse mRNA transcriptome or in those Alphavirus mRNAs lacking DLPs (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure S1B). These results show that the occurrence of DLPs in Alphavirus is probably linked to a flattening of the preceding region, resulting in a valley-peak topology for this region of mRNA.

Figure 1.

Probing the RNA structure of the 5′CDS region of alphavirus mRNA 26S reveals a valley-peak topology. (A) Two dimensional (2D) models of RNA structure based on SHAPE data for the first 70–140 nt of the CDS from seven representative Alphavirus mRNAs. Models were generated using the MC-fold program. The sequences were numbered from the initiation codon (AUGi), with A being the +1 position. SHAPE reactivity was scored and ranked according to a three-color scale as shown. Nucleotides in black showed no reactivity (ND, not detected). *For SFV we detected an alternative conformation of DLP compatible with SHAPE data (Supplementary Figure S1A). (B) Plot showing the valley-peak topology found in the 5′CDS of DLP-containing Alphavirus 26S mRNA (SV, SFV, RRV, SAGV, GETV, MIDV, UNAV, BEBV, MAYV and AURAV). The averaged base pair probability (BPP) for each position is represented in vertical bars. The BPP values that differed significantly (P < 0.01, U test) from the equivalent positions in whole mRNA transcriptome (red line) are marked as solid bars.

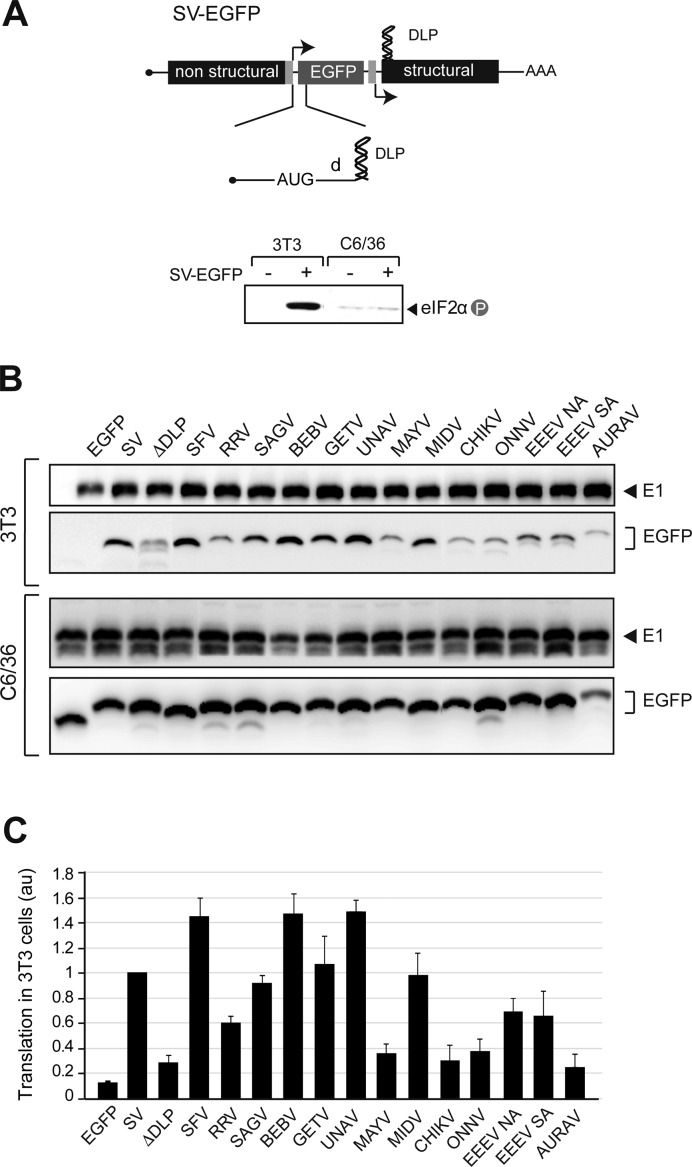

DLP activity depends on stem stability and distance to AUGi

We next tested the activity of DLPs to enable translation under eIF2 phosphorylation in the context of virus infection. To do this, the first 80–200 nt of the CDS 26S mRNA from different viruses was cloned into a SV cassette expressing the EGFP translational reporter (Figure 2A). We previously showed that addition of SV DLP to EGFP mRNA faithfully reproduced translation of SV 26S mRNA in infected cells, both in culture and in mice infected with SV (21). The ability of DLPs to enable translation could be clearly measured by comparing the accumulation of EGFP in viral-infected 3T3 fibroblasts and mosquito C6/36 cells, two cell lines that recapitulate the translational alterations observed in animals infected with these viruses (21,25). As expected, translation of EGFP mRNA was generally impaired in 3T3 cells but not in C6/36 cells (Figure 2B and C). Of note, RNA structures from SFV, SAGV, BEBV, GETV, UNAV and MIDV promoted a robust accumulation of EGFP in 3T3 cells, similar to that found in SV DLP. A less robust (but still detectable) accumulation of EGFP in WT 3T3 cells was found for RRV and EEEV RNAs, whereas EGFP was very low for MAYV, CHIKV, ONNV and AURAV RNAs. This low accumulation was comparable to that found in a SV mutant (ΔDLP) in which DLP was destroyed by point mutations (Figure 2B and C). Overall, a good correlation was found between the presence of a stable DLP structure and the ability of viral mRNAs to promote translation in 3T3 cells (except for AURAV, see below). By contrast, in C6/36 and 3T3 PKRo/o cells, the presence of viral RNA sequences exerted only a modest effect on translation of EGFP mRNA (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure S2A and B).

Figure 2.

Activity of Alphavirus DLP structures in infected cells. (A) Schematic diagram of the SV cassette expressing a translational reporter mRNA (EGFP). The alphaviral RNA structures (80–200 nt) were cloned into the 5′extreme of EGFP CDS as described in methods. The mRNA encoding EGFP is transcribed from a duplicated subgenomic promotor (27). d is the distance from AUGi to DLP. Lower panel shows eIF2 phosphorylation in 3T3 and C6/36 cells infected with SV-EGFP. (B) Representative Western blot of EGFP accumulation in 3T3 (upper panels) and C6/36 (lower panels) cells infected with the indicated recombinant SV-EGFP viruses and analyzed at 6 and 8 hpi, respectively. Note the differences in the mobility of EGFP bands due to the addition of extra coding sequences of DLPs. The extent of infection in each case was measured by the accumulation of viral glycoproteins (E1). (C) Quantification of DLP activity in promoting translation of EGFP mRNA in infected 3T3 cells (under extensive eIF2 phosphorylation). Data are the mean of at least four independent experiments ± SEM.

To test the importance of DLP positioning in translation, we systematically modified the length of d (the distance from AUGi to the base of DLP) in SV DLP by deleting or inserting A+C-rich triplets that did not affect the overall structure of DLP (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure S3). A previous report by Frolov and Schlesinger (22) showed that a 9 nt insertion or deletion upstream of the DLP structure reduced translation by 70–80% in BHK21 cells transfected with SV replicons expressing a reporter mRNA fused in-frame to the DLP structure. We found a lower limit of 25 nt for DLP activity, whereas the upper limit probably extended 50–60 nt from the AUGi since DLP placed at 49 nt lost 50–60% of its activity (Figure 3B). Thus, DLP activity peaked when it was placed at 25 and at 34–40 nt from the AUGi (d = 28 for SV), and dropped sharply when the distance was reduced to 22 nt (Figure 3A and B). Further shortening of the distance between DLP to AUGi reduced translation even in the presence of active eIF2, especially in mosquito C6/36 cells where no EGFP accumulation was detected when d was reduced to 13–16 nt (Figure 3A and B). This result agrees well with previous data (22). When DLP was moved away from the optimal position (d = 25–28), its activity decreased slowly from d = 40 to reach 50% of control when DLP was placed at d = 49. In good agreement with this, the values of d in alphaviral DLPs cluster around 27–31, with the notable exception of AURAV where DLP is probably too close to the AUGi (d = 18) to allow an efficient initiation.

Figure 3.

DLP activity depends on AUG-DLP spacing. (A) The AUG-DLP distance (d) in SV was changed by triplet insertions or deletions. Representative Western blots of EGFP and viral E1 accumulation in 3T3 and C6/36 cells infected with the indicated recombinant viruses are shown. (B) Quantification of translation in 3T3 (under extensive eIF2 phosphorylation, black bars) and in C6/36 cells (dashed line) promoted by the SV DLP placed at different d. Data were obtained as described in Figure 2 and expressed as the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. Lane 1 (-) corresponds to EGFP mRNA with no DLP. Values of d found in Alphavirus DLPs fell within 27–31 nt range (bracket), except for AURAV (gray dot). (C) DLP activity mainly correlated with the stability at the base of the stem. Translation activities in 3T3 cells for the fourteen viral DLPs were taken from Figure 2 and were plotted against the stability of the first stretch of helix (from the base to the first bulge or internal loop). This was estimated by the MFold programme (49). The goodness-of-fit for a linear regression is shown (R2). The value corresponding to AURAV DLP (gray dot) clearly deviated from the rest.

Correlation analysis showed that, under an optimal distance to AUGi, the stability at the base of stem was the parameter that best correlated with DLP activity (R2 = 0.822) (Figure 3C), whereas the stability of whole DLP or its length showed only a residual correlation with activity (R2 = 0.12 and 0.01, respectively).

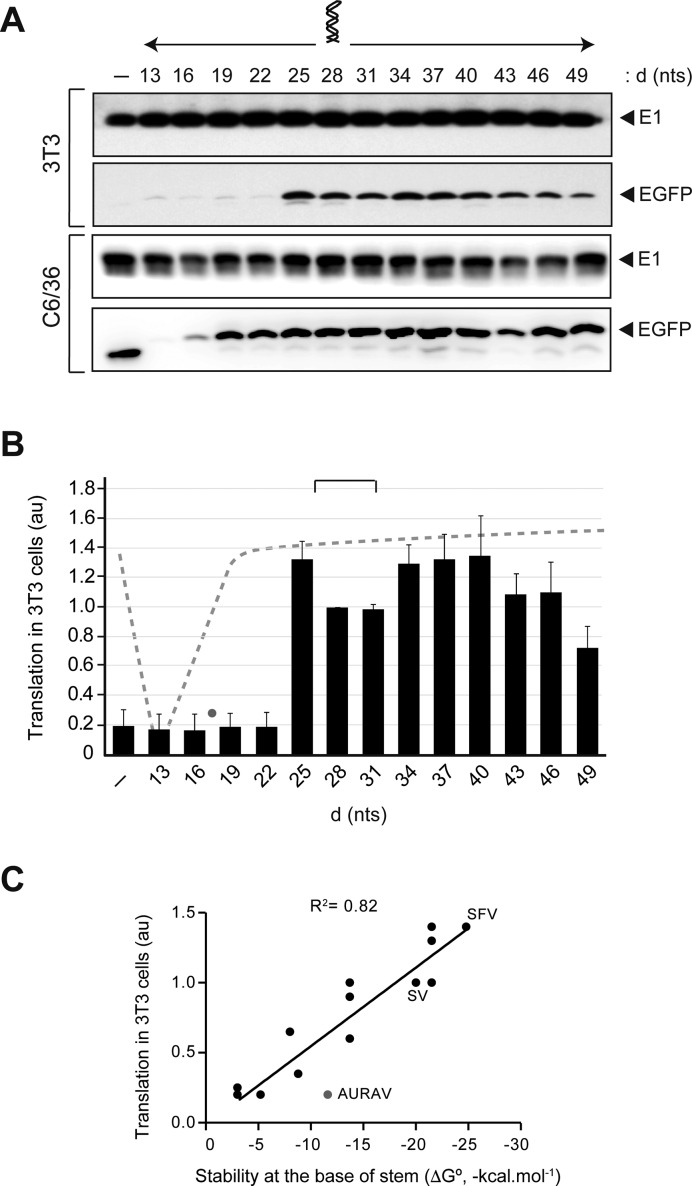

Translation of Alphavirus mRNA is scanning-dependent

We reported previously that the 5′UTR+DLP region of 26S SV mRNA was unable to promote internal translation initiation when placed between two cistrons (20). Moreover, recent data suggest that translation of SV 26S mRNA involves scanning of 40S subunit with a low requirement for eIFs as suggested previously (20,38,39). To further confirm this, we inserted stems of different stability (−30 kcal mol−1 for SL-30 and −50 kcal mol−1 for SL-50) in the 5′UTR of the translation reporter EGFP-DLP mRNA (Figure 4A), and their effect on translation in three different cell lines were tested (7). The insertion of a poorly structured sequence of equivalent length did not affect translation, whereas the SL-50 completely abolished EGFP accumulation in the three cell lines (Figure 4B). The extent of inhibition by SL-30 was dependent on the cell type used. Accordingly, insertion of SL-30 reduced translation by 10% and 50% in C6/36 and PKRo/o cells, respectively. In WT 3T3 cells, however, the presence of SL-30 inhibited translation by 80% (Figure 4B and C). These results demonstrate that translation initiation of alphavirus 26S mRNA is scanning-dependent, and that the unwinding capacity of the 43S complex, or even the binding of 43S to mRNA with stable SLs in the 5′UTR, can be reduced by eIF2 inactivation.

Figure 4.

Effect of upstream SLs on translation. (A) Folded structures of SL-30 and SL-50. 2D predictions were carried out using MC-fold. Initiation codon is underlined. (B) Insertion of stable SLs within the 5′ UTR inhibited translation of alphavirus mRNA. SLs or an unstructured sequence of equivalent length (US) were inserted in the 5′UTR of SV-DLP EGFP cassette immediately before the AUGi codon (arrow). Each cell type was infected with the indicated virus at a moi of 25 pfu/cell for 6 h and extracts were probed with anti-EGFP and anti-E1 antibodies. (–) corresponds to no sequence inserted. (C) Quantification of EGFP accumulation was normalized by the level of viral E1 in each case. Data are the mean of two independent experiments.

DLP is trapped in the ES6S region of 18S rRNA during scanning

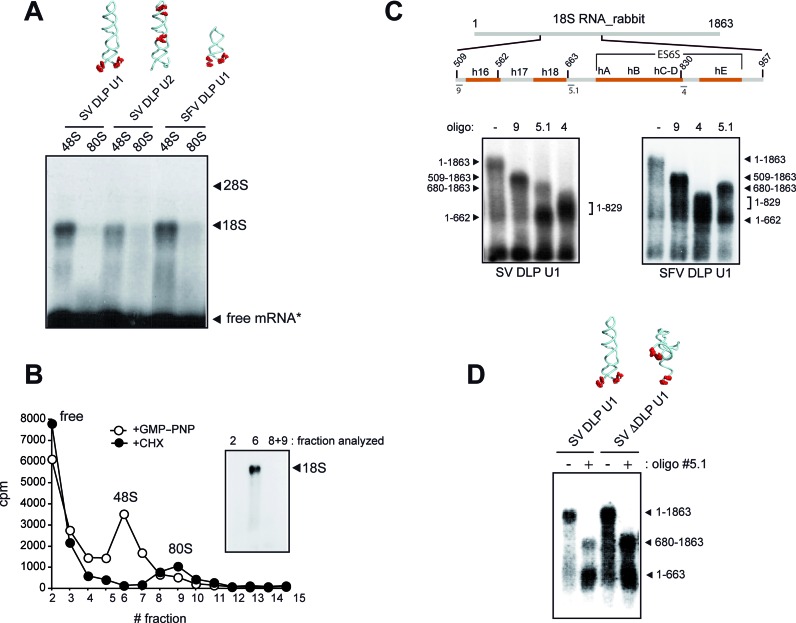

We next sought to understand how DLP works during translation initiation of SV and SFV mRNA. The distance from AUGi to DLP (130 Å for a partially stretched RNA strand) suggested that DLP probably locked in a region of the solvent side of 40S subunit during scanning. To pinpoint this position, we performed crosslinking experiments using minimal versions of SV and SFV 26S mRNAs that included DLP structures. We included photoactivatable 4-thio-UTP (4SU) at specific positions of these mRNA to map the direct contacts (zero length) with rRNA and proteins along the mRNA channel of rabbit 40S subunit as described previously (40). Using this approach, Pisarev et al. were able to crosslink the nucleotide +11 of a synthetic mRNA with ribosomal proteins 2 and 3 (rpS2/3) in the 48S complex, confirming that the first 10–12 nt downstream of the AUGi of mRNA are threaded into the mRNA binding cleft of the 40S subunit. We prepared [α −32P]-labeled mRNAs with 4SU flanking the base of DLP, or in the middle of the stem and in the apical loop (Figure 5A). For initiation complex assembly, we chose RRL because translation of both SV and SFV mRNA is very efficient in these extracts. Despite the high levels of eIF2 found in RRL, we reasoned that DLP should be placed in the same region of 48S irrespective of the presence of eIF2 in the 48S complex. We first assembled 48S complexes with a non-hydrolyzable GTP analog (GMP–PNP), and the resulting products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and blotting to detect contacts with rRNA (Figure 5A). The SV and SFV DLP RNAs containing 4SU flanking the base of DLP (U1) were efficiently crosslinked to an RNA band with the size of 18S rRNA, suggesting that the base of DLP contacts some region of 18S rRNA. The SV RNA DLP U2 was also crosslinked to 18S rRNA, but to a lesser extent. Crosslinking of mRNA with 18S rRNA dissappeared when initiation complexes were allowed to proceed toward 80S step using CHX instead of GMP-PNP (Figure 5A). To confirm this, we isolated 48S and 80S complexes assembled with SV DLP U1 RNA by centrifugation in sucrose gradients and the crosslinked products were analyzed as described before. Crosslinking to 18S rRNA was detected only in 48S complexes (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

DLP interacts with solvent side regions of 18S rRNA. (A) Analysis of rRNA crosslinked to [α-32P]-labeled mRNAs containing 4SU residues at the indicated positions (red dots in RNA structures). In U1 RNAs, the 4SU are flanking the base of the DLP (positions 25, 27, 91 and 93 for SV and 27, 29, 62 and 64 for SFV), whereas in SV U2 RNA the 4SU residues are in the middle of the stem (positions 40 and 41) and in the loop (positions 54, 59 and 61). In all cases, the +1 position corresponds to the A of the initiation codon. The indicated RNAs were assembled into 48S (+GMP−PNP) or into 80S (+CHX) complexes, and equivalent amounts of ribosomal bound mRNA (104 cpm) were analyzed by electrophoresis in denaturing 1% agarose gels, followed by transfer to nylon membrane and autoradiography. The positions of rRNA bands and free mRNA (*) are indicated. (B) SV RNA contacted 18S rRNA only in 48S complexes. RRL were programmed with [α−32P] SV-DLP U1 RNA in the presence of GMP-PNP or CHX. The lysates were crosslinked and centrifuged in a 10–35% sucrose gradient for 2 h at 40 000 rpm and fractionated. The RNA in the 48S and 80S peaks (3 × 103 cpm) was analyzed as described above. (C) RNase H mapping of mRNA-18S rRNA contacts. Schematic diagram of rabbit 18S rRNA showing the position of helices 16 and 18 and those that form the ES6S region located in the solvent side of 40S subunit. Numbers denote the nucleotide positions in rabbit 18S rRNA sequence (NR_033238.1). Some of the primers used for RNase H mapping are also shown. Below is a representative analysis of RNase H digestion with some of these primers. (D) Crosslinking of +28 position of SV mRNA with 18S rRNA was independent of the presence of a stable DLP structure. RNase H mapping of mRNA-18S rRNA contacts in 48S complex assembled with WT or ΔDLP mRNAs. The oligonucleotide used for RNase H analysis was 5.1.

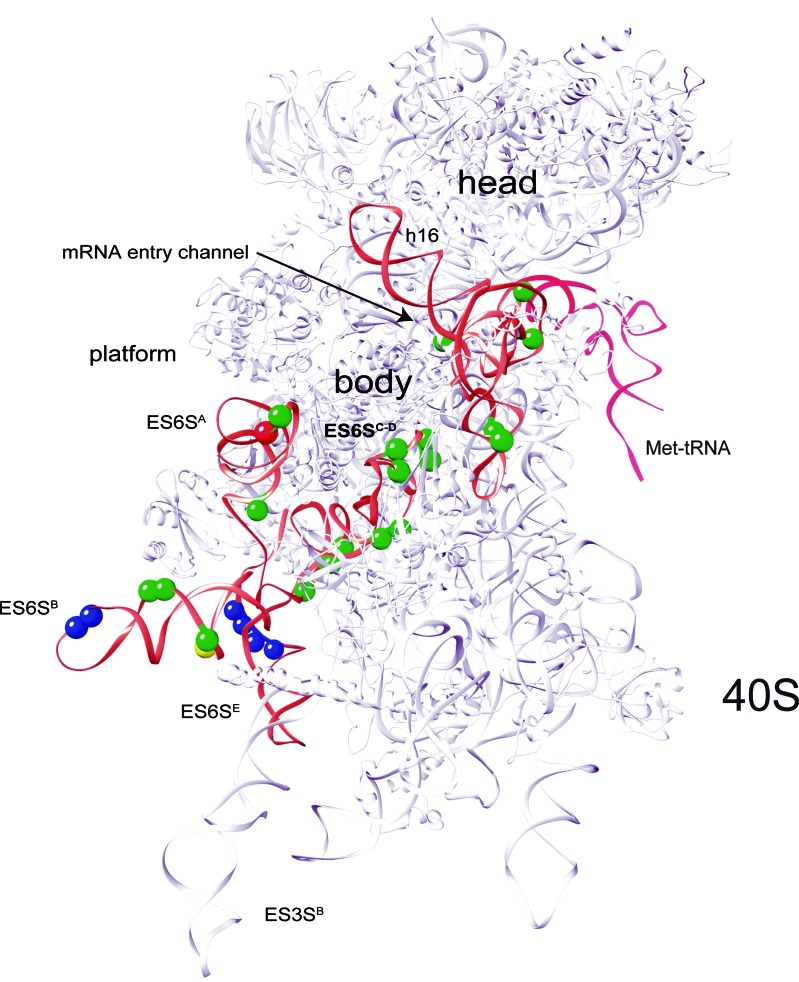

To map the region in 18S rRNA that contacted with SV DLP U1 in 48S complexes, we first carried out RNase H mapping using DNA oligonucleotides spanning different regions of rabbit 18S rRNA as described (31). An initial mapping with oligonucleotides 9 and 3 showed that DLP contacts were concentrated in the 509–936 nt fragment of 18S rRNA (Supplementary Figure S4). Next, RNAse H assay with oligonucleotide 5.1 generated two fragments of crosslinked 18S rRNA (1–662 and 680–1863) (Figure 5C). By combining these data with those derived from RNase H digestion with oligonucleotides 9 and 4, we concluded that the crosslinking sites of mRNA concentrated in regions from 509 to 662 nt and from 680 to 829 nt of rRNA 18S (Figure 5C). Fragment spanning 509 to 662 nt included the h16–h18 helices located at the mRNA entry channel, whereas the region spanning 680 to 829 nt included the ES6S RNA elements (Figure 5C). Within this region, the ES6SB stem is projected perpendicularly from the solvent side of 40S subunit near the feet, and together with the contiguous ES6SA, ES6SC-D and ES3S, they form a bundle of tentacle-like structures specific to eukaryotic ribosomes (33,34). Notably, both SV WT and SV ΔDLP U1 RNAs presented a similar crosslinking pattern, showing that interaction of +28 position of SV mRNA with 18S rRNA was independent of the presence of downstream RNA structure (Figure 5D). We next identified the crosslinking sites in 18S rRNA using primer extension arrest as described (40). To do this, we used an unlabeled version of DLP U1 RNA with 4SU and a poly(A) tail of 35 nt, allowing us to purify the crosslinked products by oligo (dT)25 beads (see Materials and Methods). As shown in Figure 6 and in Supplementary Figure S5, 15–17 crosslinking sites were detected in the ES6S region of 18S rRNA that were concentrated in helices B, C–D and A. As expected, we also detected crosslinking with some residues of h16 and h18 of rRNA that are located at the ‘classical’ mRNA entrance of the 40S subunit, and also into the mRNA channel. The SV DLP U2 RNA, however, generated only 2 contacts in ES6SA and ES6SB, the latter being coincident with that generated by SV DLP U1 RNA. As expected, many identified residues that crosslinked with DLP RNAs are in projected regions of 18S rRNA helices, but we also detected many residues in the base of ES6SB and in ES6SC that are in contact with the underlying ribosomal proteins of the 40S subunit (Figure 6). Conversely, we also detected a few residues that became less prone to primer extension arrest upon DLP RNA binding, an observation that suggested conformational changes in the ES6S region (Supplementary Figure S5).

Figure 6.

Identification of SV DLP-18S rRNA crosslinking sites in rabbit 40S subunit crystal. The data correspond to primer extension arrests identified in three independent experiments. For clarity, the ES6S and h16–18 regions are highlighted in orange. Crosslinking sites generated by SV-DLPU1 mRNA with 18S rRNA are marked with green balls, whereas SV-DLPU2 mRNA generated only two consistent crosslinkings in ES6S region of 18S rRNA (red and yellow balls, being the yellow one coincident with SV-DLPU1). Data are the average of a least three independent experiments. The contacts of eIF4G with 18S rRNA that have been mapped previously (43) are marked as blue balls.

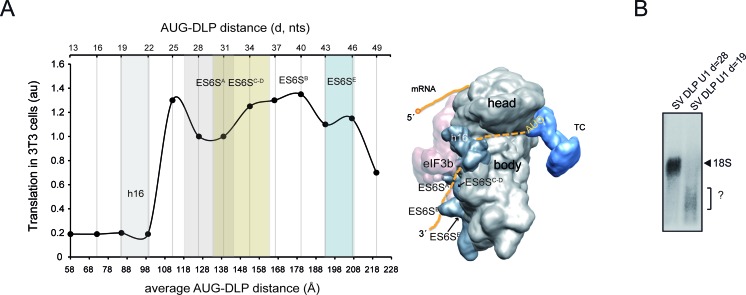

By modeling the placement of the mRNA through the ES6S region of the 40S subunit, we found that those placements of DLP that promoted translation in 3T3 cells could be easily fitted in the ES6S region, contacting some of the RNA stems that form this region (Figure 7A). Accordingly, DLP at d = 19 that is predicted to be placed upstream of the ES6S region when the AUGi is in the P site, and that was unable to support translation in 3T3 cells, showed no apparent crosslinking to the 18S rRNA in the 48S complex (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Placements of DLP that promoted translation in 3T3 cells can be fitted in the ES6S region. (A) Data from Figure 3B were plotted against the average AUG-DLP distance (Å) in SV 26S mRNA calculated using a rise per base of 4.5 Å (32). To calculate this, we measured the distances according to a hypothetical path of mRNA from the ‘classical’ mRNA entrance (60 Å from the P site) down, passing through ES6SA and ES6SB (model on the right). The areas occupied by h16 and ES6S helices in the 40S subunit crystal are approximately represented in the 2D plot (color columns). A simplified model of the 48S initiation complex showing the path of mRNA along the solvent side of 40S subunit body is shown. The ternary complex (TC) and the approximate location of AUGi are also indicated. (B) Analysis of mRNA-18S rRNA crosslinking using SV U1 RNAs bearing DLP at 28 nt (WT) or at 19 nt from the AUG. The analysis was carried as described in Figure 5C. The identity of the RNA band marked as ? in SV DLP U1 d = 19 is unknown.

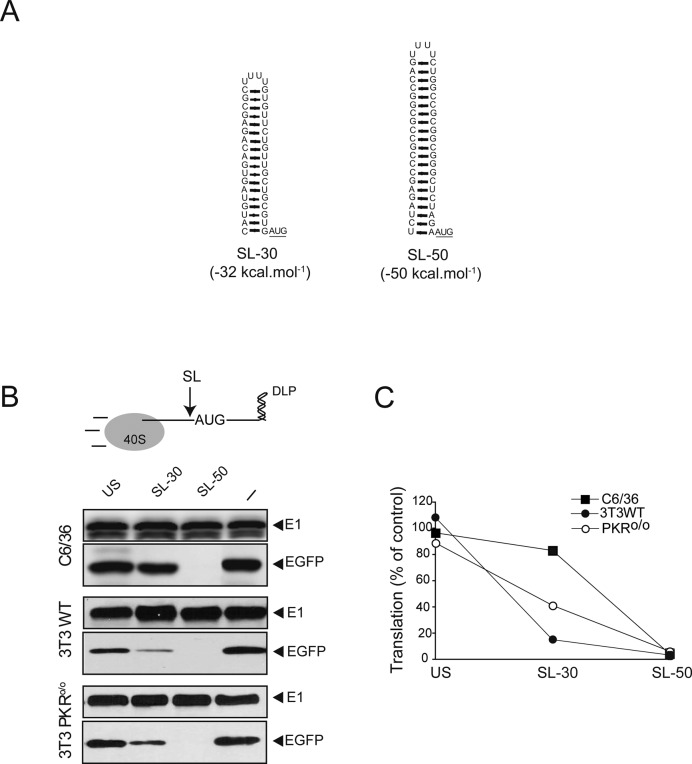

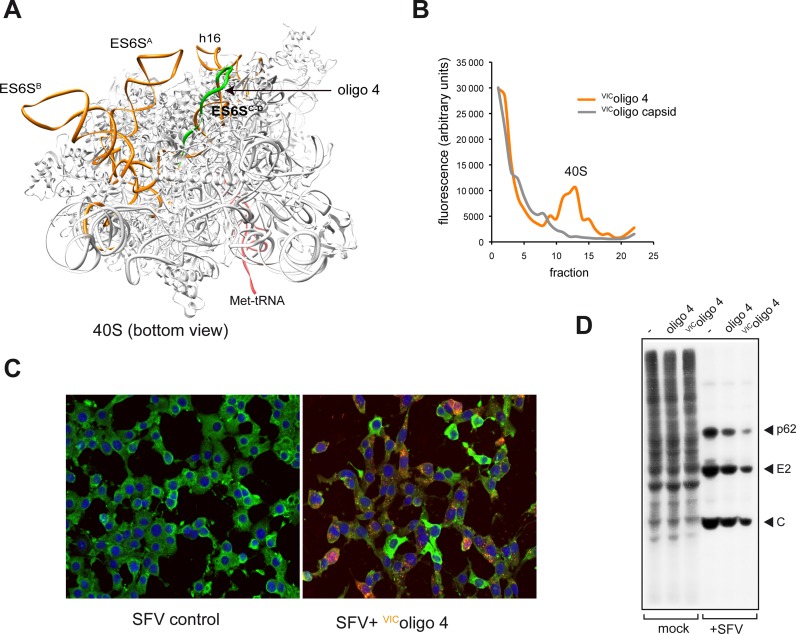

An oligonucleotide targeted to ES6SD helix blocks Alphavirus mRNA translation

Since most contacts of DLP concentrated in the ES6SC-D region, we tested the effect of an antisense oligonucleotide (oligo 4) targeted to ES6SD helix on translation of Alphavirus mRNAs in 3T3 cells (Figure 8A). This oligonucleotide was originally designed to map the region of 18S rRNA involved in RNA–RNA contacts (Figure 5C), and we used a version of this oligonucleotide conjugated to the VIC® fluorophore to detect this in transfected cells. We first confirmed that this oligonucleotide bound the 40S subunit in vitro as anticipated (Figure 8B). Upon transfection in 3T3 cells, we typically detected VIC fluorescence in >80% of cells as early as 6 h post-transfection. The presence of VIColigo 4 did not affect the overall translation at early after post-transfection (10–15 h, Figure 8D), although cell proliferation is clearly affected at later times (manuscript in preparation). Of note, transfection of VIColigo 4 significantly reduced the number of infected cells expressing SFV C protein (encoded by 26S mRNA, Figure 8C). Using metabolic labeling with [35S]-Met/Cys, we found that translation of 26S mRNA was clearly reduced in the presence of VIColigo 4 without affecting the typical shut-off of host translation induced by these viruses (Figure 8D), indicating that the binding of VIColigo 4 to the ES6S region blocked translation of alphavirus 26S mRNA without affecting early events of RNA synthesis or translation of genomic mRNA (Figure 8D). Unlabeled oligo 4 exerted only a modest inhibition on SFV translation as compared with VIColigo 4, suggesting that the fluorophore linked to oligo 4 blocks the proper positioning of DLP-mRNA in this region necessary for translation initiation.

Figure 8.

Effect of VIColigo 4 on translation of alphavirus 26S mRNA. (A) Bottom view of rabbit 40S subunit crystal structure showing the region ES6SC-D where oligo 4 hybridizes (marked in green). (B) Binding of VIColigo 4 to rabbit 40S subunit. Approximately 50 pmol of purified rabbit 40S subunit was incubated with 200 pmol of VIColigo 4 or VICSVcapside (negative control, (20)) for 20 min at 30°C and centrifuged in a 10–30% sucrose gradient at 45 000 rpm for 3 h. The fluorescence of VIC fluorochrome in each fraction was measured in a FLUOstar OPTIMA apparatus. (C) Effect of VIColigo 4 on accumulation of SFV C protein analyzed by immunofluorescence using a polyclonal antibody raised against SFV C protein. Note that those cells showing strong VIC fluorescence (orange-red) showed little SFV C staining (green). (D) Effect of VIColigo 4 on translation of 26S mRNA in SFV-infected cells. Cells were transfected with the indicated oligonucleotide, and 15 h later infected with SFV at a moi of 25 pfu/cell. The cells were metabolically labeled with [35S]-Met/Cys at 6 hpi. Labeled proteins were analyzed by autoradiography. p62, E1 and C are the structural proteins of the virus encoded by the 26S mRNA.

DISCUSSION

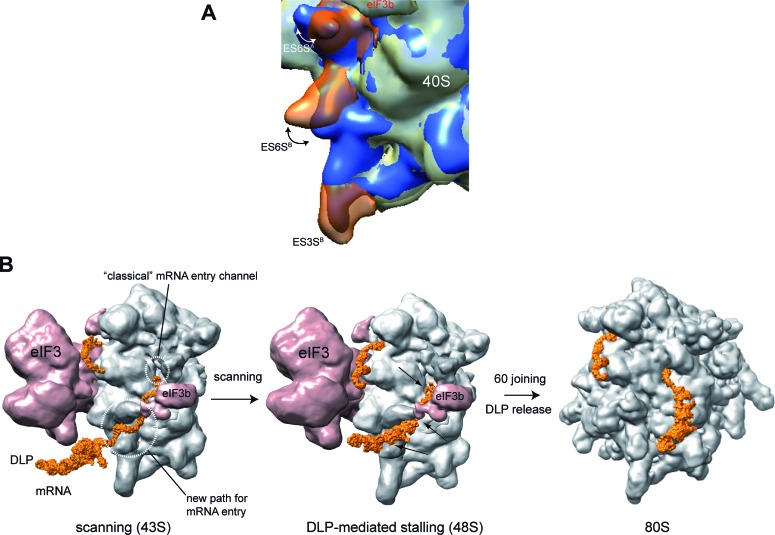

As mRNA enters the ribosome from the solvent side of the 40S subunit, the topology of this region is expected to influence the unwinding activity of the 43S-mRNA complex necessary for codon inspection during the scanning process. By studying the effect of Alphavirus DLP structures on mRNA translation, we have found an unanticipated role of rRNA segments (ES6S) in the scanning process, acting as a network of ‘sticky tenctacles’ at the leading edge of scanning 43S complex. The finding that DLP contacted with ES6S A, B and C–D helices in 48S complex supports the notion that a substantial fraction, if not all, of viral mRNA passes through this region before entering the classical mRNA entry channel. Thus, viral mRNA is probably threaded into the 40S subunit earlier than previously thought, extending by up to 150 Å the path that mRNA follows along the 40S subunit before reaching the P site (11,14,26). Moreover, the multiple contacts of DLPs along the ES6S region support the existence of slightly different placements of mRNA on this region during the scanning process. Subtle stochastic differences in the arrangement of incoming mRNA, or even differences in the topology of ES6S region among ribosomes, might determine the exact point where DLP is stalled. Our results using the VIColigo 4 suggest that it can inhibit translation of 26S SFV mRNA by blocking the channel formed by ES6SA and eIF3b in the 43S complex (Figure 9B), reinforcing the notion that mRNA passes through this region before reaching the upstream mRNA entry channel, and that this path is important for DLP-induced ribosome stalling. Interestingly, a dynamic arrangement of ES6S region has been previously proposed and recently supported by crystallographic data of the 40S subunit, and by comparative analysis of 80S EM models from different species (32,34,41). Our results support the existence of such conformational changes in ES6S regions upon 60S joining, especially for ES6SA, which might release the tension of RNA–RNA contacts necessary to release the DLP from the the ES6S region (Figure 9A). Nevertheless, the existence of an active process involving ribosomal proteins that could displace the DLP from this region cannot be ruled out.

Figure 9.

A model for 43S complex scanning and DLP function. (A) Evidence for conformational changes in ES6S helices after 60S joining. Superposition of the cryo-EM density maps of 43S pre-initiation complex (EMD-5658) and 80S ribosome (EMD-5326) showing the changes in the arrangement of ES6SA and ES6SB. The 40S subunits corresponding to 43S and 80S are displayed in gray and blue, respectively. ES6SA, ES6SB and ES3SB of 43S complex are highlighted in transparent orange. Double-head arrows denote the in and out changes in the conformation of helix ES6SA showing a displacement of ∼35 Å, and the collapse undergone by helix ES6SB with a displacement of ∼15 Å. (B) Model of 43S scanning and DLP function in viral mRNA translation. We propose that viral mRNA enters through the ES6S region of 43S. One possible placement of DLP (orange) trapped in the ES6S region of 48S complex is shown, although other slightly different topologies may also be compatible with the crosslinking experiments. The main crosslinking sites of mRNA with the ES6S region in 48S complex are indicated with black arrows. Stalling allows the AUGi of viral mRNA to be placed on the P site of 40S subunit (not visible). Upon 60S joining, the conformational changes in initiation complex trigger the release of DLP. For simplicity, the rest of initiation factors involved in ribosome scanning were omitted.

Alphavirus mRNAs can exploit the topology of the mRNA entry path in the 40S subunit by creating stable DLP structures that are trapped in the ES6S region, in such a way that resists the unwinding activity of the 43S complex during the scanning process. Thus, the highest DLP activities were found in those Alphaviruses that contained the most stable DLP structures (e.g. SFV and SV). Moreover, the AUG-DLP spacing in Alphavirus 26S mRNA is tuned to the topology of the ES6S region in a way that allows the placement of the AUGi in the P site of the 40S subunit stalled by the DLP, allowing the incorporation of Met-tRNA without the participation of eIF2. Our results, together with previous reports, support the notion that the 40S subunit could reach the AUGi of viral mRNA through an unconventional scanning process with low requirements for eIF2 and eIF4F (38,39). Most likely, this process requires the participation of eIF3, which could confer processivity to the scanning ribosome. This hypothesis is supported by the finding that eIF3 can promote the binding of SV 26S mRNA to the 40S subunit in the absence of eIF4F and eIF2 in vitro, suggesting that eIF3 might be required to translate SV 26S mRNA efficiently in infected cells (24). The proposed arrangement of DLP on the 40S subunit solvent side is compatible with a canonical eIF2-dependent initiation, although in this case the presence of DLP would be unnecessary for AUGi location. This situation is found in mosquito cells and 3T3 PKRo/o cells infected with SV, and in the reticulocyte lysates used in this work where the high availability of ternary complex in 43S probably imposed an eIF2-dependent initiation.

The fact that both WT and ΔDLP SV mRNAs generated a similar pattern of crosslinking with 18S rRNA demonstrates that this path for mRNA entry is not exclusive for mRNAs bearing extensive secondary structure downstream of the initiation codon, suggesting that cellular mRNAs could also follow this path to enter the 40S subunit during the scanning process. Based on the novel findings described here, we propose that the ES6S region constitutes the leading edge of the scanning 43S complex bound to viral mRNA (Figure 9B). In this model, eIF4F could also accommodate near the ES6S region, with eIF4A ready to unwind the eventual structure of the incoming mRNA by alternating cycles of binding and dissociation from mRNA (14,42). This proposed location for eIF4F in the 43S-mRNA complex is supported by previous data showing that the middle domain of eIF4G (eIF4G-MD) contacts with ES6SE and ES6SB projections of 40S subunit when initiation complexes are assembled in the presence of viral mRNA (43). Moreover, ES6SE and ES6SB are relatively close to the head and the right arms of eIF3 in the 43S complex, two domains of eIF3 involved in the binding to eIF4G (33,44,45). Thus, eIF3e (right arm), eIF3c (head) and eIF3d subunits interact with eIF4G-M to promote the attachment of the eIF4F–mRNA complex to the mammalian 43S complex (46,47). This U-shaped arrangement from the ES6S region to the exit channel region agrees with several previous findings (14,33,48), and presents a working model for the scanning complex that will require further confirmation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Luis Menendez′s lab for helping us with acrylamide gels for sequencing and Juanjo Berlanga and Miguel Angel Rodriguez Gabriel for their support and discussions. Institutional support from the Fundación Ramón Areces is also acknowledged. Completion of this project took approximately 3 years and the estimated cost was 10000, excluding salaries.

Footnotes

Present address: René Toribio, Centro de Biotecnología y Genómica de Plantas, UPM-INIA, Madrid, Spain.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación [BFU2010-17411]. Funding for open access charge: Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación [BFU2010-17411].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sharp P.A. The centrality of RNA. Cell. 2009;136:577–580. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White H.B., 3rd, Laux B.E., Dennis D. Messenger RNA structure: compatibility of hairpin loops with protein sequence. Science. 1972;175:1264–1266. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4027.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woese C.R., Winker S., Gutell R.R. Architecture of ribosomal RNA: constraints on the sequence of ‘tetra-loops’. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:8467–8471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tinoco I., Jr, Bustamante C. How RNA folds. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;293:271–281. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bevilacqua P.C., Blose J.M. Structures, kinetics, thermodynamics, and biological functions of RNA hairpins. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2008;59:79–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.59.032607.093743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pelletier J., Sonenberg N. Insertion mutagenesis to increase secondary structure within the 5′ noncoding region of a eukaryotic mRNA reduces translational efficiency. Cell. 1985;40:515–526. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kozak M. Circumstances and mechanisms of inhibition of translation by secondary structure in eucaryotic mRNAs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1989;9:5134–5142. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.11.5134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Svitkin Y.V., Pause A., Haghighat A., Pyronnet S., Witherell G., Belsham G.J., Sonenberg N. The requirement for eukaryotic initiation factor 4A (elF4A) in translation is in direct proportion to the degree of mRNA 5′ secondary structure. RNA. 2001;7:382–394. doi: 10.1017/s135583820100108x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babendure J.R., Babendure J.L., Ding J.H., Tsien R.Y. Control of mammalian translation by mRNA structure near caps. RNA. 2006;12:851–861. doi: 10.1261/rna.2309906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pelletier J., Sonenberg N. Internal initiation of translation of eukaryotic mRNA directed by a sequence derived from poliovirus RNA. Nature. 1988;334:320–325. doi: 10.1038/334320a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson R.J., Hellen C.U., Pestova T.V. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:113–127. doi: 10.1038/nrm2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parsyan A., Svitkin Y., Shahbazian D., Gkogkas C., Lasko P., Merrick W.C., Sonenberg N. mRNA helicases: the tacticians of translational control. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;12:235–245. doi: 10.1038/nrm3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Garcia C., Frieda K.L., Feoktistova K., Fraser C.S., Block S.M. RNA BIOCHEMISTRY. Factor-dependent processivity in human eIF4A DEAD-box helicase. Science. 2015;348:1486–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marintchev A., Edmonds K.A., Marintcheva B., Hendrickson E., Oberer M., Suzuki C., Herdy B., Sonenberg N., Wagner G. Topology and regulation of the human eIF4A/4G/4H helicase complex in translation initiation. Cell. 2009;136:447–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Futterer J., Kiss-Laszlo Z., Hohn T. Nonlinear ribosome migration on cauliflower mosaic virus 35S RNA. Cell. 1993;73:789–802. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90257-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abaeva I.S., Marintchev A., Pisareva V.P., Hellen C.U., Pestova T.V. Bypassing of stems versus linear base-by-base inspection of mammalian mRNAs during ribosomal scanning. EMBO J. 2011;30:115–129. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pisareva V.P., Pisarev A.V., Komar A.A., Hellen C.U., Pestova T.V. Translation initiation on mammalian mRNAs with structured 5′UTRs requires DExH-box protein DHX29. Cell. 2008;135:1237–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soto-Rifo R., Rubilar P.S., Limousin T., de Breyne S., Decimo D., Ohlmann T. DEAD-box protein DDX3 associates with eIF4F to promote translation of selected mRNAs. EMBO J. 2012;31:3745–3756. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Namy O., Moran S.J., Stuart D.I., Gilbert R.J., Brierley I. A mechanical explanation of RNA pseudoknot function in programmed ribosomal frameshifting. Nature. 2006;441:244–247. doi: 10.1038/nature04735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ventoso I., Sanz M.A., Molina S., Berlanga J.J., Carrasco L., Esteban M. Translational resistance of late alphavirus mRNA to eIF2alpha phosphorylation: a strategy to overcome the antiviral effect of protein kinase PKR. Genes Dev. 2006;20:87–100. doi: 10.1101/gad.357006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toribio R., Ventoso I. Inhibition of host translation by virus infection in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:9837–9842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004110107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frolov I., Schlesinger S. Translation of Sindbis virus mRNA: analysis of sequences downstream of the initiating AUG codon that enhance translation. J. Virol. 1996;70:1182–1190. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1182-1190.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frolov I., Schlesinger S. Translation of Sindbis virus mRNA: effects of sequences downstream of the initiating codon. J. Virol. 1994;68:8111–8117. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8111-8117.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skabkin M.A., Skabkina O.V., Dhote V., Komar A.A., Hellen C.U., Pestova T.V. Activities of Ligatin and MCT-1/DENR in eukaryotic translation initiation and ribosomal recycling. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1787–1801. doi: 10.1101/gad.1957510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ventoso I. Adaptive changes in alphavirus mRNA translation allowed colonization of vertebrate hosts. J. Virol. 2012;86:9484–9494. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01114-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinnebusch A.G. Molecular mechanism of scanning and start codon selection in eukaryotes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011;75:434–467. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00008-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hahn C.S., Hahn Y.S., Braciale T.J., Rice C.M. Infectious Sindbis virus transient expression vectors for studying antigen processing and presentation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:2679–2683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilkinson K.A., Merino E.J., Weeks K.M. Selective 2′-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension (SHAPE): quantitative RNA structure analysis at single nucleotide resolution. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:1610–1616. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parisien M., Major F. The MC-Fold and MC-Sym pipeline infers RNA structure from sequence data. Nature. 2008;452:51–55. doi: 10.1038/nature06684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Popenda M., Szachniuk M., Antczak M., Purzycka K.J., Lukasiak P., Bartol N., Blazewicz J., Adamiak R.W. Automated 3D structure composition for large RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e112. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dontsova O., Dokudovskaya S., Kopylov A., Bogdanov A., Rinke-Appel J., Junke N., Brimacombe R. Three widely separated positions in the 16S RNA lie in or close to the ribosomal decoding region; a site-directed cross-linking study with mRNA analogues. EMBO J. 1992;11:3105–3116. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lomakin I.B., Steitz T.A. The initiation of mammalian protein synthesis and mRNA scanning mechanism. Nature. 2013;500:307–311. doi: 10.1038/nature12355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hashem Y., des Georges A., Dhote V., Langlois R., Liao H.Y., Grassucci R.A., Hellen C.U., Pestova T.V., Frank J. Structure of the mammalian ribosomal 43S preinitiation complex bound to the scanning factor DHX29. Cell. 2013;153:1108–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anger A.M., Armache J.P., Berninghausen O., Habeck M., Subklewe M., Wilson D.N., Beckmann R. Structures of the human and Drosophila 80S ribosome. Nature. 2013;497:80–85. doi: 10.1038/nature12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ludtke S.J., Baldwin P.R., Chiu W. EMAN: semiautomated software for high-resolution single-particle reconstructions. J. Struct. Biol. 1999;128:82–97. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scheres S.H., Nunez-Ramirez R., Sorzano C.O., Carazo J.M., Marabini R. Image processing for electron microscopy single-particle analysis using XMIPP. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:977–990. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C., Ferrin T.E. UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia-Moreno M., Sanz M.A., Carrasco L. Initiation codon selection is accomplished by a scanning mechanism without crucial initiation factors in Sindbis virus subgenomic mRNA. RNA. 2015;21:93–112. doi: 10.1261/rna.047084.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castello A., Sanz M.A., Molina S., Carrasco L. Translation of Sindbis virus 26S mRNA does not require intact eukariotic initiation factor 4G. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;355:942–956. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pisarev A.V., Kolupaeva V.G., Yusupov M.M., Hellen C.U., Pestova T.V. Ribosomal position and contacts of mRNA in eukaryotic translation initiation complexes. EMBO J. 2008;27:1609–1621. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Melnikov S., Ben-Shem A., Garreau de Loubresse N., Jenner L., Yusupova G., Yusupov M. One core, two shells: bacterial and eukaryotic ribosomes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:560–567. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rajagopal V., Park E.H., Hinnebusch A.G., Lorsch J.R. Specific domains in yeast translation initiation factor eIF4G strongly bias RNA unwinding activity of the eIF4F complex toward duplexes with 5′-overhangs. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:20301–20312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.347278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu Y., Abaeva I.S., Marintchev A., Pestova T.V., Hellen C.U. Common conformational changes induced in type 2 picornavirus IRESs by cognate trans-acting factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:4851–4865. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Querol-Audi J., Sun C., Vogan J.M., Smith M.D., Gu Y., Cate J.H., Nogales E. Architecture of human translation initiation factor 3. Structure. 2013;21:920–928. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.des Georges A., Dhote V., Kuhn L., Hellen C.U., Pestova T.V., Frank J., Hashem Y. Structure of mammalian eIF3 in the context of the 43S preinitiation complex. Nature. 2015;525:491–495. doi: 10.1038/nature14891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.LeFebvre A.K., Korneeva N.L., Trutschl M., Cvek U., Duzan R.D., Bradley C.A., Hershey J.W., Rhoads R.E. Translation initiation factor eIF4G-1 binds to eIF3 through the eIF3e subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:22917–22932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605418200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Villa N., Do A., Hershey J.W., Fraser C.S. Human eukaryotic initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) protein binds to eIF3c, -d, and -e to promote mRNA recruitment to the ribosome. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:32932–32940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.517011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nielsen K.H., Behrens M.A., He Y., Oliveira C.L., Jensen L.S., Hoffmann S.V., Pedersen J.S., Andersen G.R. Synergistic activation of eIF4A by eIF4B and eIF4G. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:2678–2689. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.