Abstract

Background

Portable motion transducers, suitable for measuring tremor, are now available at a reasonable cost. The use of these transducers requires knowledge of their limitations and data analysis. The purpose of this review is to provide a practical overview and example software for using portable motion transducers in the quantification of tremor.

Methods

Medline was searched via PubMed.gov in December 2015 using the Boolean expression “tremor AND (accelerometer OR accelerometry OR gyroscope OR inertial measurement unit OR digitizing tablet OR transducer).” Abstracts of 419 papers dating back to 1964 were reviewed for relevant portable transducers and methods of tremor analysis, and 105 papers written in English were reviewed in detail.

Results

Accelerometers, gyroscopes, and digitizing tablets are used most commonly, but few are sold for the purpose of measuring tremor. Consequently, most software for tremor analysis is developed by the user. Wearable transducers are capable of recording tremor continuously, in the absence of a clinician. Tremor amplitude, frequency, and occurrence (percentage of time with tremor) can be computed. Tremor amplitude and occurrence correlate strongly with clinical ratings of tremor severity.

Discussion

Transducers provide measurements of tremor amplitude that are objective, precise, and valid, but the precision and accuracy of transducers are mitigated by natural variability in tremor amplitude. This variability is so great that the minimum detectable change in amplitude, exceeding random variability, is comparable for scales and transducers. Research is needed to determine the feasibility of detecting smaller change using averaged data from continuous long-term recordings with wearable transducers.

Keywords: Tremor, transducer, accelerometry, measurement, Fourier analysis

Introduction

Transducers have been used in the study of tremor for more than 100 years. Early investigators used a tambour and smoked drum to record physiologic and pathologic tremors.1 Accelerometers were introduced more than 50 years ago to elucidate tremor mechanisms and to quantify tremor.2-4 Early accelerometric studies required laboratory-based equipment that was bulky and expensive. These analog devices required a cable that connected the transducer to a bulky power supply, amplifier, and filters. The amplified signals were often stored on a magnetic tape recorder prior to digitization by an analog–digital converter for computer analysis. In the 1970s, the cost of an accelerometer ($1,000–$3,000), filters and amplifiers ($1,000–$3,000), software (>$1,000), analog–digital converters (>$1,000), and a computer (>$20,000) was prohibitive for most clinicians. The computer alone was the size of a small refrigerator!

The expense and size of transducers decreased dramatically with the advent of microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) technology in the 1990s. Small transducers are now integrated with microelectronic circuits for data acquisition and storage. Inertial measurement units (IMUs) contain a triaxial accelerometer, triaxial gyroscope, and frequently a triaxial magnetometer and altimeter, integrated with an electronic circuit for digital storage and wireless output.5 The cost of, and space required for, computing have plummeted with the development of portable laptop computers that have ample memory and computing power. Meanwhile, portable computer graphics tablets became available6,7 and are being used to quantify tremor in writing and drawing.8-12

The purpose of this review is to provide a practical overview of the use of portable motion transducers in the quantification of tremor. This is not a comprehensive review of all transducers that are currently being sold for the assessment of tremor; rather it is a practical guide to the selection and use of portable transducers in tremor analysis. MEMS technology has provided developers with an abundance of inexpensive IMUs that are being incorporated into a variety of devices that are potentially useful in the assessment of tremor. The list of such devices and applications is rapidly increasing and changing with advancing technology. Witness, for example, the Lift Pulse app for Android13 devices that uses the IMU in smart phones to measure tremor. Also consider the accelerometers and gyroscopes in wrist-worn activity monitors and smart watches.5,14 Those with sufficient range, sensitivity, and bandwidth are potentially useful for the measurement of tremor.

Accelerometers, gyroscopes, and digitizing tablets are considered in this review because they have been used most commonly to assess tremor in ambulatory settings. Their strengths, limitations, and methods of analysis are reviewed. Example software for tremor analysis is provided in an online appendix.

Methods

Medline was searched via PubMed.gov in December 2015 using the Boolean expression “tremor AND (accelerometer OR accelerometry OR gyroscope OR inertial measurement unit OR digitizing tablet OR transducer).” This search produced 419 papers dating back to 1964. The abstracts of these papers were reviewed for relevant portable transducers and mathematical methods of tremor analysis, and 105 papers written in English were reviewed in detail. Potentially relevant publications and references cited in these publications were also reviewed.

Results and Discussion

Properties of motion

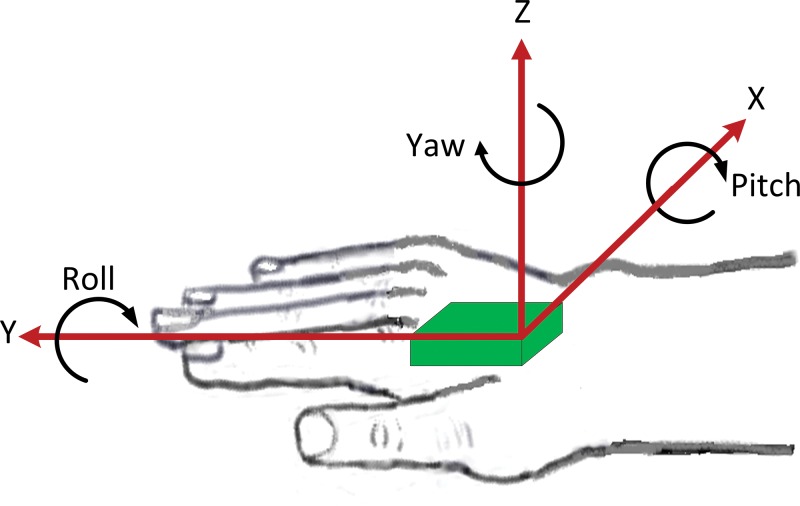

Motion of a body part (e.g., the hand) may consist of translational motion and rotational motion in three-dimensional space (Figure 1). In other words, a body part may exhibit any combination of anteroposterior, lateral, and vertical translation, and it can rotate about the anteroposterior (roll), lateral (pitch), and vertical (yaw) axes.

Figure 1. Cartoon of a Motion Sensor (Green) Mounted on the Dorsum of the Hand. In general, tremor in a body part will consist of rotation and translation in three-dimensional space. Many modern motion sensors contain a triaxial accelerometer and gyroscope for capturing this motion.

Tremor is an oscillatory motion that is roughly sinusoidal. Fourier’s theorem states that almost any continuous, periodic signal can be represented by the weighted sum of sines and cosines.15 The Fourier transform mathematically decomposes a signal into a series of sine and cosine waves. The amplitudes of the sines and cosines reveal the magnitudes of oscillation at the frequencies of motion. A plot of these amplitudes versus frequency is called an amplitude frequency spectrum. For example, if the signal is Asin(ωt), the amplitude frequency spectrum is a spike of magnitude A at frequency ω, and the so-called power (amplitude squared) spectrum is a spike of magnitude A2 at frequency ω. The mathematical details of these methods are described in many references on signal analysis.15

The fast Fourier transform (FFT) is a discrete Fourier transform that is computed with a mathematical algorithm that minimizes the number of computations, thus optimizing computational speed on a computer. This algorithm is implemented in many software packages. For example, Microsoft Excel provides an FFT that will accept signal recordings consisting of N data points, where N must be some integer power of 2 (e.g., 28 = 256), up to 4,096 (see online appendix). Other FFTs, such as those in MATLAB (www.mathworks.com) and Python (www.python.org), have fewer restrictions.

The frequency content of voluntary movement is generally concentrated at frequencies below 2 Hz, and most forms of tremor occur at 3 Hz or greater.16 An exception is myorhythmia, which is a rare form of slow tremor at <4 Hz.17 Voluntary movements are usually sufficiently arrhythmic that they do not produce a distinct spectral peak in the amplitude spectrum. Consequently, the frequency content of voluntary movement is usually distinguished easily from tremor.18,19 However, jerky voluntary and involuntary movements (e.g., chorea, myoclonus) contain high-frequency content that may extend into the frequency range of tremor. Tremor must be distinguished from these movements on the basis of rhythmicity, which usually results in a narrow spectral peak with a half-bandwidth of 2 Hz or less. Half-bandwidth is the width of the spectral peak at one-half the peak amplitude in the power spectrum or at 0.707 peak amplitude in the amplitude spectrum. Rhythmicity can also be quantified in terms of the variability in the period of successive tremor cycles.20,21 These methods are usually combined with high-pass filtering to separate low-frequency movement from tremor.20,21

Selecting a transducer

Several factors are important when selecting a transducer for tremor analysis. The kinematic characteristics of tremor and motor task must be considered, and the transducer must have sufficient sensitivity, amplitude range, and frequency range to record tremor with good fidelity. The transducer also must be small enough and light enough to mount securely on the desired body part, without impeding the motor task. These issues are now discussed.

Characteristics of tremor and choice of transducer

Translational displacement tremor T can be approximated by a sine wave with amplitude A in centimeters and frequency f in cycles per second (i.e., Hertz, Hz): T = Asin(2πft). Similarly, rotational tremor R can be expressed as R = θsin(2πft), where θ is the amplitude in degrees. Translational and angular velocities are the first derivatives of T and R: A(2πf)cos(2πft) and θ(2πf)cos(2πft), and translational and angular accelerations are the second derivatives of T and R: −A(2πf)2sin(2πft) and −θ(2πf)2sin(2πft). Therefore, if translational acceleration is measured, the amplitude of translational velocity is acceleration divided by 2πf, and translational displacement is acceleration divided by (2πf)2. Similarly, if angular velocity is measured, angular rotation is the amplitude of angular velocity divided by 2πf, and angular acceleration is angular velocity times 2πf. Accelerometers measure translational acceleration, and gyroscopes measure angular velocity. Digitizing tablets measure the translational displacement of a pen on the tablet surface.

Most tremors are primarily oscillatory rotation of a body part about a joint or multiple joints. For example, hand tremor may originate from tremulous rotation at the wrist, elbow, or shoulder. Similarly, head tremor is primarily rotation of the head about the neck. Consequently, a gyroscope mounted on the hand or head would seem ideal. However, until the advent of MEMS technology, gyroscopic transducers were too heavy and bulky for most tremor applications. These transducers are now very small and inexpensive.

Historically, accelerometers have been used more than other transducers in tremor analysis. Most accelerometers are piezoelectric, piezoresistive, or capacitive devices and have been incorporated into a variety of wearable devices.22,23 Capacitive MEMS accelerometers are now used most commonly in human motion analysis. These accelerometers record inertial acceleration and Earth’s gravitational force g (1 g = 9.8 m/second2). Inertial acceleration of a body part is a function of the force F applied to the mass m of the body part, according to Newton’s law F = ma. The effect of Earth’s gravity on an accelerometer is not constant when the accelerometer is rotating in space, and some rotational movement is virtually always present when recording tremor.24 Gravitational force will fluctuate between ±1 g as a single-axis accelerometer rotates in space. For example, if a single-axis accelerometer is rotated slowly at 1 Hz, the output recording will be a sinusoidal oscillation with frequency 1 Hz and amplitude 1 g. Accelerometers are designed to be sensitive to translation (linear acceleration), not angular rotation, so if an accelerometer is mounted precisely at the axis of rotation, its output will be entirely gravitational artifact. This gravitational artifact cannot be removed by high-pass filtering because it will be present at all frequencies of motion. Theoretically, multiple accelerometers, strategically mounted on a body part, can be used to estimate inertial acceleration, free of gravitational artifact.24,25 Note that translational inertial acceleration of ±1 g (= ±9.8 m/second2) at 1 Hz would require a peak-to-peak amplitude of displacement equal to 2·9.8/(2π1)2 = 0.496 m, so gravitational artifact can be considerable.

Gyroscopic transducers record angular velocity. Ideally, they are free of gravitational artifact, but all commercially available gyroscopes suitable for tremor analysis have some sensitivity to gravity and linear acceleration.26,27 This source of error is negligible unless angular velocity is integrated over time to compute angular rotation. Since tremor is roughly sinusoidal, its amplitude can be estimated by dividing angular velocity by 2πf, thus avoiding the cumulative error produced by numerically integrating a gyroscopic signal with drift and low-amplitude translational and gravitational acceleration artifact. Angular velocity is the same at any point on a rotating rigid body, so the location of a gyroscope is not critical, in contrast to accelerometry. The total angular velocity can be computed from a triaxial gyroscope as ω = (ωx2+ωy2+ωz2)0.5, where ωx is the angular velocity about the x-axis and so on.

Many commercially available motion sensors have a triaxial accelerometer and triaxial gyroscope housed in a single IMU, and a magnetometer and altimeter are also commonly included. Examples of such recording systems are presented in Table 1, and additional examples are the Shimmer3 (www.shimmersensing.com/) and Xsens IMUs (www.xsens.com/tags/imu/). IMUs have been designed for numerous applications, including automotive and aerospace sensors, personal electronic devices (smart phones, smart watches, tablets, computers, and game controllers), cameras, and wearable activity monitors. Many manufacturers (e.g., Fairchild, Analog Devices, InvenSense, Kionix, Colibrys, Motorola, Sensonor, Delphi) have produced an abundance of devices suitable for a wide range of applications (www.sens2b-sensors.com/directory/inertial-systems-motion/inertial-measurement-unit-imu). Each transducer has several important performance specifications, including number of axes, amplitude range, sensitivity, resolution, accuracy, bandwidth, noise, drift, mass, and size.5

Table 1. Examples of Motion Transducers and their Technical Specifications.

| Sensor | Axes | Range | Mass | Resolution | Accuracy | Sampling Rate (samples/s) | Recording Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinesia One | |||||||

| Accelerometer | 3 | ±5 g | 8.5 grams | 12 bit | ±2% | 64 | 8 hr |

| Gyroscope | 3 | ±2000 deg/s | ±4% | 64 | 8 hr | ||

| ADPM Opal | |||||||

| Accelerometer | 3 | ±6 g or ±2 g | 22 grams | 14 bit | 2% | 20-128 | 12-24 hr** |

| Gyroscope | 3 | ±2000 deg/s* | 2% | ||||

| ActiGraph GT9X | |||||||

| Accelerometer | 3 | ±16 g | 14 grams | 16 bit | 3% | 100 | >24 hr |

| Gyroscope | 3 | ±2000 deg/s | 4% | 100 | |||

| Wacom Intuos tablets | 2 | ≥10 cm*** | ≥700 grams*** | 0.005 mm | ±0.25 mm | ≥100 | As long as the pen is on the tablet |

±2000 deg/s for axes X and Y, and ±1500 deg/s for axis Z

Depends on sampling rate: 12 hr when data are sampled at 128/s

Depends on the size of the tablet

The suitability of a transducer depends on the characteristics of tremor (amplitude and frequency) vis-à-vis the technical specifications of the transducer. The frequency of tremor must fall within the frequency range (bandwidth) of the transducer, and the largest anticipated tremor amplitudes should fall within the reported amplitude range of the transducer. For example, suppose the largest anticipated hand tremor amplitude is 30 cm peak to peak with a frequency of 4 Hz (a very severe tremor!). A good estimate of tremor acceleration is A(2πf)2, where A is half the peak-to-peak displacement amplitude and f is tremor frequency. Thus, our largest anticipated tremor acceleration is 9,478 cm/second2 or 9.67 g, so if we also account for the gravitational effect, the accelerometer should have a range of at least ±11 g. Similarly, for a 4 Hz 60-degree peak-to-peak severe rotational tremor, the maximum angular velocity is θ(2πf) = 754 degrees/second (θ = 30 degrees and f = 4 Hz), and the gyroscope should have a range of at least ±1,000 degrees/second.

Another important consideration is the resolution of the transducer. Until recently, most motion transducers were analog devices that produced a continuous voltage that was proportional to the physical property being measured (e.g., acceleration or angular velocity). The analog signal was sampled or digitized with a separate analog-to-digital converter, interfaced with a digital computer. The resolution of the analog-to-digital (A/D) converter was some power of 2. For example, 8-bit A/D conversion sampled the analog signal at 28 = 256 increments or levels, 12-bit A/D conversion at 4,096 levels, and 16-bit A/D conversion at 65,536 levels. Many transducers are now digital and either have built-in A/D converters or use pulse-width modulation to produce voltage pulses with a width that is proportional to acceleration or angular velocity. In all cases, the available increments of measurement are some power of 2 (e.g., 12 bit, 14 bit or higher). A 12-bit resolution produces output readings in 4,096 increments. Thus, if the range of the transducer is −6 g to +6 g, the resolution is 12 g/4,096 = 0.00293 g per increment or 2.87 cm/second2 per increment. This resolution is quite adequate for most pathologic tremors but is marginally adequate for physiologic hand (wrist) tremor, which has a mean baseline-to-peak (one-half peak-to-peak) amplitude range of 3 to 33 cm/second2 when the accelerometer is mounted 14 cm from the wrist (i.e., axis of rotation).28 Angular acceleration can be computed from these values using the equation α = a/r, where r is the distance of the accelerometer from the axis of rotation and a is the acceleration perpendicular to the axis of rotation (i.e., tangential to the curvilinear path of the accelerometer). Thus, for physiologic hand tremor, the mean amplitude range of angular acceleration is 0.214 to 2.36 radians/second2 or 12.3 to 135 degrees/second2 (2π radians = 360 degrees). Dividing these values by (2πf), where f = 8 Hz, gives the following estimates of angular velocity: 0.244 to 2.69 degrees/second. A gyroscope with range of ±2,000 degrees/second and 12-bit digitization has a resolution of 4,000/2,048 = 1.95 degrees/second, which is not adequate for physiologic hand tremor. Note, however, that this resolution can be improved by using a transducer with a lower amplitude range (e.g., ±2 g or ±1,000 degrees/second) or by selecting a transducer with more increments of digitization (e.g., 16 bit = 65,536 increments). Regardless of the resolution, the incremental value will have a small degree of inaccuracy, which is usually expressed as a percentage (e.g., ±3%) or as a range of the value (e.g., ±0.25 mm). The accuracy of digitizing tablets is considerably less than their digital resolution (Table 1).6

Motor task selection

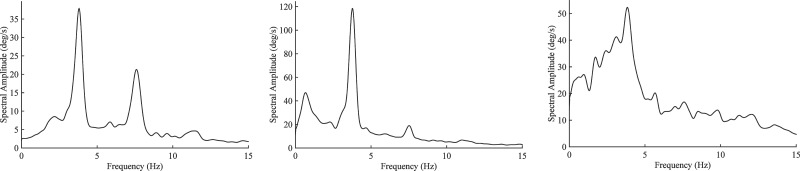

Tremor is measured when the body part is at rest (rest tremor), is voluntarily maintaining a constant posture (postural tremor), or is voluntarily moving (kinetic tremor). There is very little movement other than tremor during rest and constant posture, and any movement other than tremor will have frequency content below that of tremor. Therefore, the rhythmic oscillation of tremor is easily discernible in an amplitude or power spectrum. However, the frequency content of other voluntary or involuntary movements (e.g., chorea, myoclonus) may approach or overlap that of kinetic tremor if these movements are fast or jerky. The resulting spectrum will be a peak superimposed on a broad base of other spectral activity (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Amplitude Spectra (Degrees/Second) of Hand Tremor Recorded with a Gyroscope Transducer. Tremor was recorded from the dorsum of the hand while the upper limb was at rest, extended horizontally and anteriorly, and while performing finger-to-nose movements (graphs left to right). The patient has a Holmes tremor due to a previous midbrain hemorrhage. The tremor spectral peaks are very sharp during rest and posture. During movement, the tremor peak is superimposed on spectral activity produced by the voluntary movement. The mean tremor amplitude in degrees is the peak amplitude divided by 2πf, where f is the tremor frequency (3.8 Hz).

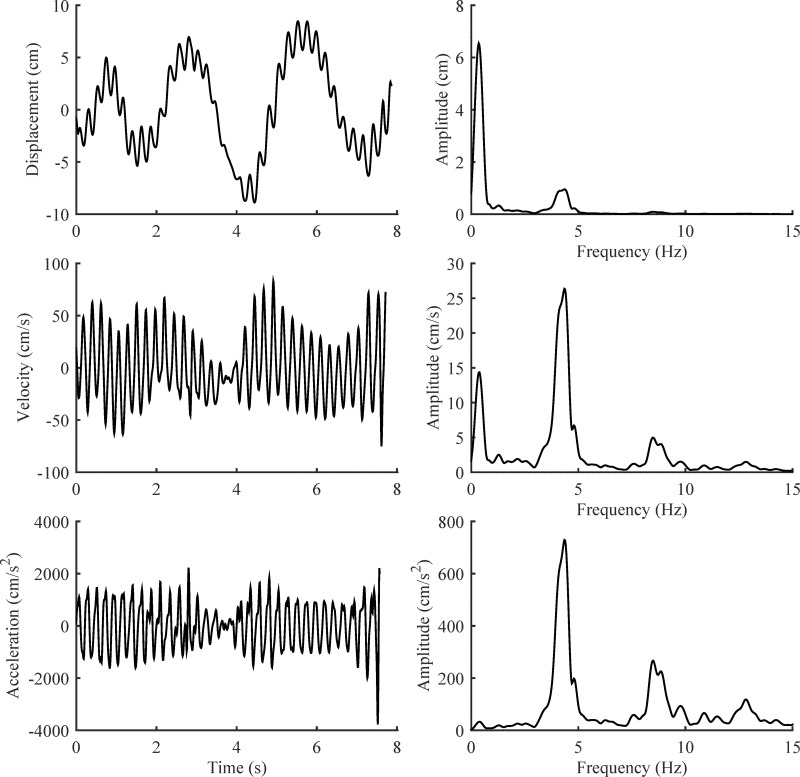

Gyroscopes and accelerometers accentuate tremor relative to lower-frequency voluntary movement because these devices record the first and second derivatives of rotation and displacement, respectively. Recall that the first derivative of a sinusoidal oscillation is a sinusoid multiplied by (2πf), and the second derivative is a sinusoid multiplied by (2πf)2. Thus, higher-frequency movement (i.e., tremor) is amplified relative to lower-frequency voluntary movement, as illustrated in Figure 3. However, other voluntary and involuntary movements will be amplified to the same extent as tremor if their frequency content is similar, and the tremor spectral peak in a frequency spectrum will be mixed with or partially obscured by other movement at the same frequency.

Figure 3. Tremor in an Archimedes Spiral Recorded with a Digitizing Tablet. In the left column, the X component of an Archimedes spiral (displacement) is shown with its first and second derivatives (velocity and acceleration), computed with a frequency impulse response differentiator in MATLAB. The power spectrum of displacement, velocity, and acceleration are shown on the right. Note how differentiation accentuates the 4.3 Hz tremor relative to the lower-frequency voluntary movement.

There are ways of mitigating the problems produced by rapid voluntary and involuntary movements. First, one can use voluntary tasks that are relatively slow, with no abrupt accelerations or decelerations. However, this approach might have little effect on other rapid involuntary movements, if they exist, and the slow voluntary movement may not be optimal for eliciting tremor. A sensor worn on the wrist during normal daily activities will record tremor and all sorts of voluntary and involuntary activity. For these recordings of spontaneous unconstrained activity, mathematical algorithms for identifying tremor must be employed, and such algorithms usually include the detection of rhythmic oscillation with spectral analysis or with some other algorithm.18-21,29

The body part being studied is another important consideration. Small body parts (e.g., the finger) require small recording devices. Many sensors for continuous monitoring of tremor are worn on the wrist like a watch, and in this location, the sensor will do a poor job of capturing tremor from rotation of the wrist and finger joints. The accelerometer in a smart phone can be programmed to record tremor, but mounting the smart phone on many body segments is difficult or impossible. The same is true for transducers housed in game controllers and other large electronic devices. Awkward or insecure mounting of a motion sensor on a body part will allow extraneous motion of the sensor and distortion of the tremor recording (i.e., motion artifact). In short, the mass, dimensions, and mounting of a motion sensor must be considered to ensure a valid recording of tremor.

Writing and drawing are favorite tasks in the assessment of upper-extremity action tremor, and digitizing tablets have sufficient resolution and accuracy to quantify tremor that is visible to the unaided eye.8 There are several manufacturers of digitizing tablets,30 but the Wacom Intuos tablets have been used almost exclusively in studies of tremor. Tablets are now portable and very affordable, and they have been used to identify pathologic tremor in genetic studies31 and to assess treatment effect in drug studies.9,11,12 Tablets lack sufficient sensitivity and accuracy to measure physiologic tremor. Consequently, drawings and writing by normal people will not produce a tremor spectral peak.32 This limitation is a strength when the goal is to identify people with abnormal tremor.31 Another limitation is that motion of the pen is not detected unless the pen tip is within 1 cm of the tablet surface, and patients with very severe tremor frequently cannot keep the pen so close to the tablet surface. Furthermore, tremor is recorded in only two dimensions and will not detect movement perpendicular to the tablet. Some pens have pressure sensors, but these sensors are nonlinear and must be calibrated. Consequently, these pressure sensors are useful in detecting tremor in pen pressure and movement of the pen from the tablet surface, but they are not useful in quantifying tremor amplitude. Finally, many tablets are sensitive to pen tilt, but this feature is not a necessity. In fact, pen-tilt sensitivity can be viewed as a source of artifact when measuring x–y motion of the pen tip, and pen-tilt sensitivity can be inactivated in many tablets.

The x–y displacements of the pen tip are transmitted digitally to a computer at 100 Hz or more. The x- and y-displacement data are numerically differentiated with frequency impulse response or Savistky–Golay differentiating filters33 to produce velocity and acceleration data that can be analyzed in a variety of ways, including Fourier analysis.6,7,9,32 Data transmission from tablet to computer requires the Wintab driver, which is supplied with all tablets. Writing data acquisition software with this driver requires considerable programming expertise. The Psychophysics toolbox version 3 (Psychtoolbox-3) for MATLAB is a free set of MATLAB programs for neuroscience research and contains MATLAB functions for interfacing tablets with MATLAB (http://psychtoolbox.org/download/). VBTablet (http://greenreaper.co.uk/#VBTablet) is a free Wintab 32-bit ActiveX component that has been used to record tablet data into 32-bit Microsoft Excel for analysis in MATLAB (see online appendix).11,12,34 There is also free tablet software for Archimedes spiral acquisition and analysis, written by Camilo Toro (http://www.neuroglyphics.org/).9

Tremor analysis

Tremor is an oscillatory movement, and all methods of analyzing recordings of tremor capitalize on this property. Here, we focus on Fourier spectral analysis because it is used most commonly. However, time-domain analyses20,21 and other frequency-domain analyses35–37 are also available. All of these methods are easily accomplished with MATLAB and its signal analysis toolbox (www.mathworks.com) or with Python and its SciPy library (www.scipy.org). Example software is provided in the online appendix.

Analog transducers produce a continuous voltage that is typically amplified, filtered, and then digitized with an A/D converter and computer. The sampling rate of the A/D converter must be at least twice the highest frequency in the transducer signal to avoid a phenomenon called aliasing, in which frequencies that are greater than half the sampling rate (i.e., Nyquist folding frequency) appear at lower “aliased” frequencies, according to the equation fa = |n·fs − f|, where fa is the aliased frequency, fs is the sampling rate, and n is the closest integer multiple of the sampling rate to the frequency f that is being aliased. For example, if the sampling rate is 100 Hz but there is noise at 60 Hz, the 60 Hz noise will appear at 40 Hz in the frequency spectrum. Aliasing can be avoided by using a sufficiently high sampling rate and by low-pass filtering the transducer signal to remove high-frequency noise. If the transducer is a digital device, then the user must make sure that the sampling rate is adequate and that the bandwidth of the transducer encompasses the frequency range of tremor and associated movement. Most portable transducers (IMUs) are now digital, but the digitizing frequency must still be at least twice the highest frequency in the transducer signal. Some activity monitors use sampling rates that are too low for tremor analysis.

The duration of the digitized recording will vary greatly with the application. Recording may be as short as a few seconds or may last hours or days. The frequency resolution of a frequency spectrum will be approximately 1/T, where T is the duration of the recording. Thus, the frequency resolution of a 2-second recording will be 0.5 Hz. If this is not adequate, longer recordings will be necessary. Longer recordings also may be necessary to obtain a representative sample of tremor, and the optimum recording duration will depend on the type of tremor and activity of the subject. Between 30 and 60 seconds is usually ample for postural tremor and for re-emergent rest tremor.38 Very mild rest tremor is typically very intermittent, so a 60-second recording with an augmenting task may be necessary.39 Continuous long-term recordings have also been used.21 Intention tremor may occur intermittently in certain phases of a task (e.g., as the finger approaches the nose), and 60 seconds or longer may be required to obtain representative samples. Longer recordings during prescribed activities such as holding a fixed posture or finger-to-nose testing may become impractical due to subject fatigue.

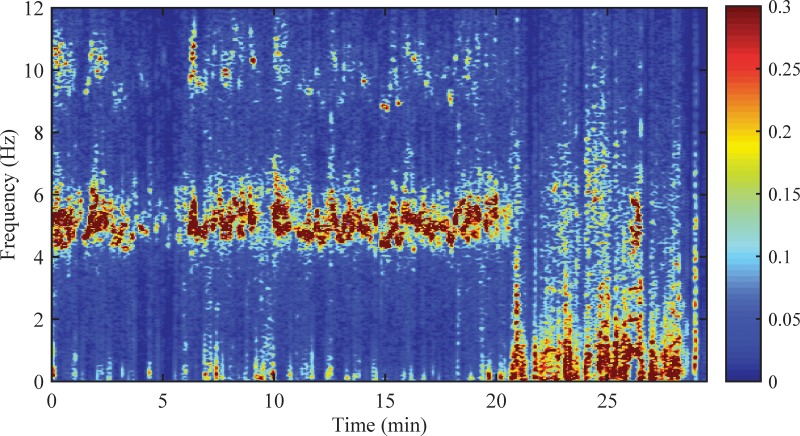

When a Fourier amplitude spectrum of a transducer recording is computed, the result is the root mean squared amplitude (0.707 peak amplitude) plotted versus time. This is appropriate when the tremor is more or less stable (statistically stationary) over time. However, many types of tremor are intermittent and are affected by a variety of external factors such as activity, stress, and medical interventions. Long-term recordings of intermittent tremor are more appropriately characterized with a time-frequency analysis that shows how the signal power and frequency change over time. The most common type of time-frequency analysis produces images called spectrograms (Figure 4). Spectrograms are created by performing spectral analysis on a series of "sliding windows." This approach is discussed by Wang and coworkers and is compared to another type of time-frequency analysis called the continuous wavelet transform, which is also known as a scaleogram.35 Example software is provided in the online appendix.

Figure 4. The Time-frequency Power Spectrum of Tremor Recorded with a Triaxial Gyroscope on the Wrist of a Patient with Parkinson Disease. This recording was made during normal uncontrolled activities. The resultant power spectrum is the sum of the power spectra of the X, Y, and Z channels. The image color intensity shows how the signal power (radians2/second2; 2π radians = 360 degrees) is distributed over time and frequency. Note how the presence and amplitude of tremor fluctuate with time. The 5 Hz tremor nearly stops at 21 minutes, when there is an abrupt increase in normal voluntary movement.

Short recordings or short segments of recordings should be multiplied by a so-called data window prior to spectral analysis to reduce a phenomenon known as spectral leakage. Spectral leakage causes spectral power from an oscillation to leak into neighboring frequencies surrounding the main spectral peak. This occurs when the frequency of the oscillation is not an integer multiple of the sampling rate divided by the number of data points in the segment being analyzed. Applying an appropriate data window (e.g., the Hanning window) reduces leakage.40 Additional information and example software are included in the online appendix.

Broad spectral peaks can be caused by random fluctuation in tremor frequency and inadequate spectral resolution, not just leakage. Spectral resolution of 0.2 Hz (5-second data segments) or 0.1 Hz (10-second data segments) is adequate for most types of tremor analysis. With this frequency resolution, broad tremor spectral peaks are often concluded to be due to fluctuation in tremor frequency. This conclusion can be corroborated with a time-frequency spectrogram (Figure 4).

It is important to recognize that all tremor recordings contain random variation in amplitude and frequency. In other words, tremor recordings are random processes or time series. Therefore, power spectra must be smoothed or averaged to obtain a spectral estimate that converges to the true spectrum of the process, without spurious spectral peaks. The most common approach is to divide a recording into L segments, compute the power spectrum of each segment, and then average the L power spectra. The variance of the power estimate at each frequency is thereby reduced by a factor of L, and the spectral estimate at each frequency is a chi-square random variable with 2L degrees of freedom.41 The 1-α confidence limits for the average spectral estimate X̂ is given in equation 1, where the spectral estimates have n = 2L degrees of freedom and χ2 is the chi-square value for n, α/2 and n, 1-α/2.15 Greater smoothing is achieved by analyzing overlapping segments, as described by Welch and used in the programs in the online appendix.41 Segment overlap of 50% results in a 33% increase in degrees of freedom, and 90% overlap produces nearly a 50% increase.42

| (1) |

The frequency resolution will be L/T Hz, where T is the duration of the recording.

Instead of spectral averaging, one may also "smooth" the spectrum of the entire recording by performing a weighted running average of sequential neighboring spectral values using a so-called spectral window, which is discussed elsewhere.43 With this method, the Fourier transform is calculated using the entire recording, instead of L segments. For long recording durations of 30 seconds or more, spectral leakage is negligible, so windowing the data series is not necessary. Bartlett’s method of smoothing M sequential frequencies in a power spectrum produces chi-square spectral estimates with n = 3M degrees of freedom, and the confidence limits can be computed with equation 1.15

Caveats

It should now be apparent that these recording and analysis procedures are not rigidly defined, and the choice of instrumentation and analysis methods requires good judgment. Anatomical placement of the transducer, selection of motor task, duration of sampling, and methods of spectral analysis may vary among users. The best or optimum protocols have not been determined, and these will vary with the type of tremor being studied, the subject population, and the context. It is necessary to acknowledge this subjectivity in the design of studies and in the reporting of clinical and experimental results.

Validity and responsiveness

Transducers mounted appropriately have obvious face validity. However, face validity is reduced when the complexity of motion is not adequately considered. An accelerometer or gyroscope mounted on the hand will record hand tremor that is produced by a combination of wrist, elbow, and shoulder oscillations if the entire limb is permitted to move. Tremor at different joints may have different frequencies, producing multiple spectral peaks, and hand motion may be affected primarily by oscillation in proximal joints, not the wrist. Consequently, when interpreting a frequency spectrum, one cannot assume that a particular joint is involved unless motion was somehow restricted to that joint. These caveats are not an issue if the purpose is simply to measure the displacement or rotation of the hand in space, but they are an issue if wrist tremor, for example, is the specific interest.

Another consideration is that motion of one body part can be affected by motion elsewhere. For example, trunk tremor may be transmitted to the limbs and head, thereby reducing the validity of head and limb recordings. All of these limitations and caveats also pertain to clinical rating scales, to which portable transducers are frequently compared. Neither is a true gold standard. The accurate measurement of tremor generated by multiple joints can be accomplished only with multiple motion transducers or complex three-dimensional motion analysis systems,18,44 which are beyond the scope of this review and the capacity of most users.

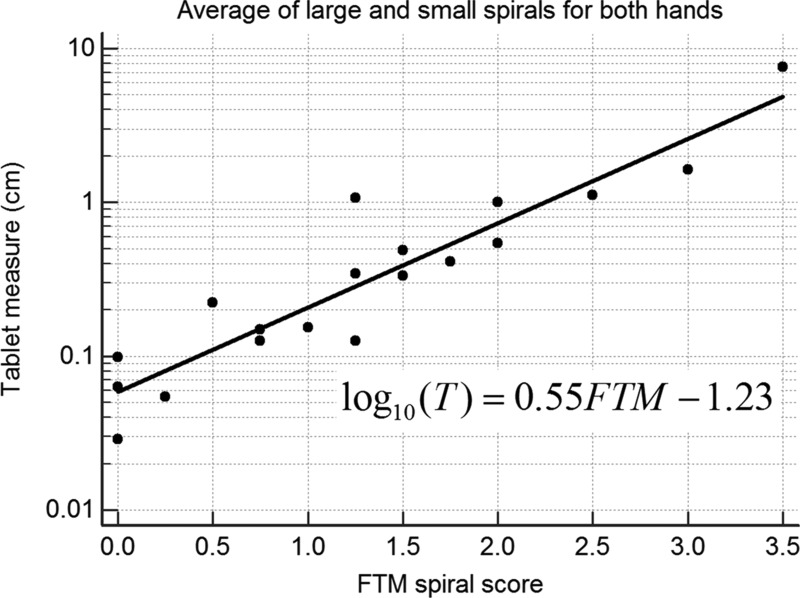

Accelerometers, gyroscopes, and tablets have good convergent validity. However, the correlation between a transducer measure of tremor and a relevant rating scale is logarithmic, not linear.45,46 The logarithmic relationship stems from the fact that clinical ratings are nonlinear measures, as predicted by the Weber–Fechner law of psychophysics.45 This law states that the detectable (perceptible) change in a measure (e.g., tremor) is proportional to the initial value. Transducers, by contrast, are linear devices, and the detectable change is determined by their sensitivity (resolution and accuracy), not by the initial value. In general, a transducer measure of tremor T is related to the tremor rating TRS as follows: log T = α·TRS+β. The correlation between a transducer measure and TRS is very strong when these assessments are performed simultaneously (Figure 5). Correlations are less when the assessments are not performed simultaneously45 because tremor amplitude fluctuates greatly over time.47–49

Figure 5. Tremor from 19 Patients with Essential Tremor Recorded with a Digitizing Tablet while Each Patient drew the Large and Small Archimedes Spirals of the Fahn–Tolosa–Marín (FTM) Scale. The average tremor amplitude (T) and average tremor rating (FTM) of the four spirals (two with each hand) are plotted on a log base 10 scale. The regression line and equation are shown. A logarithmic relationship between transducer measure and tremor rating has been found for all transducers used in tremor studies.

The great precision and accuracy of transducers are mitigated by amplitude variability of tremor over time. This was learned in the pilot trial of the At Home Testing Device for quantitative assessment of Parkinson disease.50 In this study, patients performed weekly in-home assessments of tremor, reaction time, speech, and finger dexterity with a small portable system of transducers, including a wrist-worn accelerometer. None of these measures exceeded the sensitivity of the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale motor score in detecting progression of disease over 6 months. This surprising result is largely explained by the large within-subjects variability of tremor and other motor functions. Change due to disease or treatment cannot be detected until it exceeds this natural variability. Statistically, this change is called minimum detectable change (MDC). MDC = SEM·1.96·√2, where the standard error of the measurement SEM is the square root of the within-subjects residual mean squared error (within-subjects variability) in a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA).51 Variability in tremor is by far the biggest source of test-retest variability, but variability in transducer mounting and analysis may also contribute. Regardless, the test-retest variability in tremor is so large that the MDC for transducers is comparable to that of a good rating scale,34,52 and the average of multiple measurements may be necessary to reduce variability.12 However, in some situations, transducers may still be preferable to rating scales because they enable tremor to be assessed more frequently with less cost, and they can be used almost anywhere, without clinician raters. Transducers may also be used to corroborate the results of clinical ratings.11,12

There is far more test-retest variability when tremor is measured continuously with a wearable transducer in an ambulatory setting because tremor and activity vary throughout the day. Nevertheless, continuous long-term recordings produce far more measurements of tremor, which can be averaged to reduce variability. One can also compute the times and percentage of time (occurrence) that a patient has tremor. The percentage of time with tremor is a valid measure of essential tremor and Parkinson rest tremor severity,21 and correlates with patient disability.53 The use of wearable transducers is still an active area of research and development. We do not yet know if continuous recordings of tremor can detect clinical change better than rating scales or transducers used in isolated assessments with prescribed activities.

The SEM and MDC of transducer data are computed with log-transformed data because transducer data are generally positively skewed and non-Gaussian. MDC is expressed as a percentage of the baseline geometric mean, and MDC% = (1−10−MDC) 100, where MDC is on log10 scale and MDC% is the percentage decrease in the geometric mean.54 When MDC is an increase, the formula for MDC% is (1−10MDC) 100. Experimentally determined MDCs have been no better than a 50% reduction or 200% increase in the baseline geometric mean.34,52,55 This is roughly equivalent to a one point change in a 0–4 tremor rating.45

Conclusions

Portable transducers for assessing tremor are now readily available at reasonable cost, and there is no question that they can provide valid measures of tremor amplitude, occurrence, and frequency. Transducers provide very precise linear measures of tremor, in contrast to the subjective, imprecise, nonlinear measures produced by clinical ratings. However, transducers have noteworthy limitations that must be considered. In the clinical assessment of tremor severity, the precision of transducers is largely mitigated by the inherent test-retest variability in tremor amplitude, resulting in minimum detectable change values that are comparable to those of clinical ratings.

The desirability of transducers versus scales depends on many factors, not just precision, and in the final analysis, the demands of an application will determine whether the cost and complexity of transducer recording and analysis are justified vis-à-vis the relative simplicity of a clinical rating scale. Transducers can be used to assess tremor without an experienced rater, can be used repeatedly with little additional cost, can be used in most locations, and can be used to corroborate the results of clinical ratings. Wearable transducers are capable of long continuous recordings, and such recordings are potentially helpful in monitoring medication response and disease progression in ambulatory settings. Transducers are necessary to measure tremor frequency accurately and to study spontaneous fluctuations in tremor amplitude, which may provide insight into underlying tremor mechanisms.56 We predict that transducers will become increasingly popular as standardized user-friendly analysis software is developed, including software that is web-based. Example software, written in MATLAB, is included in the online appendix.

Contents of the online appendix

The online appendix for this article is available here: http://dx.doi.org/10.7916/D8N879TT/.

APPENDIX.docx describes the contents of the appendix and how to install and use the programs.

FFT example.xlsm is a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet program containing macros for computing a power spectrum.

TremorSpectrum.m and TremorSpectrum.fig is a MATLAB program with graphical user interface for analyzing data from an inertial measurement unit. For readers who do not have MATLAB, standalone executable programs are provided for Windows and Mac OS X.

TabletSpectrum.m and TabletSpectrum.fig is a MATLAB program with graphical user interface for analyzing data from a digitizing tablet. For readers who do not have MATLAB, standalone executable programs are provided for Windows and Mac OS X.

Tablet.xls is a Microsoft Windows 32-bit Excel program for sampling data with a digitizing tablet. This will not work with 64-bit Excel.

Data files: ActiGraphdata.xlsx, finger nose no mass LUE.xls, artificialdata.csv, tabletdata.csv, artificial tablet data.csv

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Spastic Paralysis Research Foundation of Kiwanis International, Illinois-Eastern Iowa District.

Financial Disclosures: Rodger Elble received grant support from the Spastic Paralysis Research Foundation of Kiwanis International, Illinois-Eastern Iowa District. He received consulting fees from Sage Therapeutics and is a paid video rater for InSightec. James McNames is an employee of and owns stock in APDM, Inc.

Conflicts of Interest: R.E. has collaborated with Great Lakes NeuroTechnologies and APDM Wearable Technologies in the development of their motion transducers. J.M. and Portland State University have a financial interest in APDM, Inc., a company that may have a commercial interest in the results of this research and technology. This potential conflict has been reviewed and managed by Oregon Health & Science University.

Ethics statement: This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards detailed in the Declaration of Helsinki. The authors' institutional ethics committee has approved this study and all patients have provided written informed consent.

References

- 1.Hsu AW, Piboolnurak PA, Floyd AG, et al. Spiral analysis in Niemann-Pick disease type C. Mov Disord. 2009;24:1984–1990. doi: 10.1002/mds.22744. doi: 10.1002/mds.22744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Randall JE, Stiles RN. Power spectral analysis of finger acceleration tremor. J Appl Physiol. 1964;19:357–360. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1964.19.2.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stiles RN, Randall JE. Mechanical factors in human tremor frequency. J Appl Physiol. 1967;23:324–330. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1967.23.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan MH, Hewer RL, Cooper R. Intention tremor – a method of measurement. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1975;38:253–258. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.38.3.253. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.38.3.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodríguez-Martín D, Pérez-López C, Samà A, Cabestany J, Català A. A wearable inertial measurement unit for long-term monitoring in the dependency care area. Sensors. 2013;13:14079–14104. doi: 10.3390/s131014079. doi: 10.3390/s131014079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elble RJ, Sinha R, Higgins C. Quantification of tremor with a digitizing tablet. J Neurosci Methods. 1990;32:193–198. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(90)90140-b. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(90)90140-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pullman SL. Spiral analysis: a new technique for measuring tremor with a digitizing tablet. Mov Disord. 1998;13:85–89. doi: 10.1002/mds.870131315. doi: 10.1002/mds.870131315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feys P, Helsen W, Prinsmel A, Ilsbroukx S, Wang S, Liu X. Digitised spirography as an evaluation tool for intention tremor in multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;160:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.09.019. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haubenberger D, Kalowitz D, Nahab FB, et al. Validation of digital spiral analysis as outcome parameter for clinical trials in essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2011;26:2073–2080. doi: 10.1002/mds.23808. doi: 10.1002/mds.23808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haubenberger D, McCrossin G, Lungu C, et al. Octanoic acid in alcohol-responsive essential tremor: a randomized controlled study. Neurology. 2013;80:933–940. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182840c4f. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182840c4f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zesiewicz TA, Sullivan KL, Hinson V, et al. Multisite, double-blind, randomized, controlled study of pregabalin for essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2013;28:249–250. doi: 10.1002/mds.25264. doi: 10.1002/mds.25264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elble RJ, Lyons KE, Pahwa R. Levetiracetam is not effective for essential tremor. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2007;30:350–356. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013E31807A32C6. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013E31807A32C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lift Pulse app for Android http://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.liftlabsdesign.liftpulse.

- 14.Dai H, Zhang P, Lueth TC. Quantitative assessment of parkinsonian tremor based on an inertial measurement unit. Sensors. 2015;15:25055–25071. doi: 10.3390/s151025055. doi: 10.3390/s151025055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bendat JS, Piersol AG. Random data: analysis and measurement procedures. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deuschl G, Bain P, Brin M. Consensus statement of the Movement Disorder Society on Tremor. Ad Hoc Scientific Committee. Mov Disord. 1998;13:2–23. doi: 10.1002/mds.870131303. doi: 10.1002/mds.870131303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baizabal-Carvallo JF, Cardoso F, Jankovic J. Myorhythmia: phenomenology, etiology, and treatment. Mov Disord. 2015;30:171–179. doi: 10.1002/mds.26093. doi: 10.1002/mds.26093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lambrecht S, Gallego JA, Rocon E, Pons JL. Automatic real-time monitoring and assessment of tremor parameters in the upper limb from orientation data. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:221. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00221. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallego JA, Rocon E, Roa JO, Moreno JC, Pons JL. Real-time estimation of pathological tremor parameters from gyroscope data. Sensors. 2010;10:2129–2149. doi: 10.3390/s100302129. doi: 10.3390/s100302129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaikh AG, Jinnah HA, Tripp RM, et al. Irregularity distinguishes limb tremor in cervical dystonia from essential tremor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:187–189. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.131110. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.131110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Someren EJ, Pticek MD, Speelman JD, Schuurman PR, Esselink R, Swaab DF. New actigraph for long-term tremor recording. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1136–1143. doi: 10.1002/mds.20900. doi: 10.1002/mds.20900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang C-C, Hsu Y-L. A review of accelerometry-based wearable motion detectors for physical activity monitoring. Sensors. 2010;10:7772–7788. doi: 10.3390/s100807772. doi: 10.3390/s100807772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.John D, Freedson P. ActiGraph and Actical physical activity monitors: a peek under the hood. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:S86–S89. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182399f5e. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182399f5e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elble RJ. Gravitational artifact in accelerometric measurements of tremor. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116:1638–1643. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.03.014. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Padgaonkar AJ, Krieger KW, King AI. Measurement of angular acceleration of a rigid body using linear accelerometers. J Appl Mech (Transactions ASME) 1975;42:552–556. doi: 10.1115/1.3423640. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bancroft JB, Lachapelle G. 2nd International Conference on Ubiquitous Positioning, Indoor Navigation and Location-Based Service. Helsinki: IEEE; 2012. Estimating MEMS gyroscope G-sensitivity errors in foot mounted navigation; pp. 1–6. http://plan.geomatics.ucalgary.ca/papers/upinlbs%202012_bancroft%202020etal_oct202012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinberg H. Gyro mechanical performance: the most important parameter. Analog Devices. 2011 Technical Article MS-2158. http://www.analog.com/media/en/technical-documentation/technical-articles/MS-2158.pdf.

- 28.Elble RJ. Physiologic and essential tremor. Neurology. 1986;36:225–231. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.2.225. doi: 10.1212/WNL.36.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaikh AG, Zee DS, Jinnah HA. Oscillatory head movements in cervical dystonia: dystonia, tremor, or both. Mov Disord. 2015;30:834–842. doi: 10.1002/mds.26231. doi: 10.1002/mds.26231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chie TY. Which graphics drawing tablet to buy in 2015 (non-display types) http://www.parkablogs.com/content/which-graphics-drawing-tablet-buy-2015-non-display-types2014.

- 31.Shatunov A, Sambuughin N, Jankovic J, et al. Genomewide scans in North American families reveal genetic linkage of essential tremor to a region on chromosome 6p23. Brain. 2006;129:2318–2331. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl120. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elble RJ, Brilliant M, Leffler K, Higgins C. Quantification of essential tremor in writing and drawing. Mov Disord. 1996;11:70–78. doi: 10.1002/mds.870110113. doi: 10.1002/mds.870110113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Savitzky A, Golay MJE. Smoothing and differentiation of data by simplified least squares procedures. Anal Chem. 1964;36:1627–1639. doi: 10.1021/ac60214a047. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akano E, Zesiewicz T, Elble R. Fahn-Tolosa-Marin scale, digitizing tablet and accelerometry have comparable minimum detectable change. Mov Disord. 2015;30:S556. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang SY, Aziz TZ, Stein JF, Liu X. Time-frequency analysis of transient neuromuscular events: dynamic changes in activity of the subthalamic nucleus and forearm muscles related to the intermittent resting tremor. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;145:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.12.009. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torrence C, Compo GP. A practical guide to wavelet analysis. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 1998;79:61–78. doi: 10.1175/1520-0477(1998)079<0061:APGTWA>2.0.CO;2. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ayache SS, Al-Ani T, Farhat WH, Zouari HG, Creange A, Lefaucheur JP. Analysis of tremor in multiple sclerosis using Hilbert-Huang Transform. Neurophysiol Clin. 2015;45:475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2015.09.013. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jankovic J, Schwartz KS, Ondo W. Re-emergent tremor of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:646–650. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.5.646. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.5.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cleeves L, Findley LJ, Gresty M. Assessment of rest tremor in Parkinson’s disease. Adv Neurol. 1986;45:349–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Understanding FFTs windowing National Instruments. 2015 http://www.ni.com/white-paper/4844/en/

- 41.Welch PD. The use of fast Fourier transform for the estimation of power spectra: a method based on time averaging over short, modified periodograms. IEEE Trans Audio Electroacoust. 1967;AU-15:70–73. doi: 10.1109/TAU.1967.1161901. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Welch PD. On the relationship between batch means, overlapping batch means, and spectral estimation. In: Thesen A, Grant H, Kelton WD, editors. Proceedings of the 1987 Winter Simulation Conference. New York: ACM; 1987. pp. 320–323. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jenkins GM, Watts DG. Spectral analysis and its applications. San Francisco, CA: Holden-Day; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rajaraman V, Jack D, Adamovich SV, Hening W, Sage J, Poizner H. A novel quantitative method for 3D measurement of Parkinsonian tremor. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111:338–343. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(99)00230-8. doi: 10.1016/S1388-2457(99)00230-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elble RJ, Pullman SL, Matsumoto JY, Raethjen J, Deuschl G, Tintner R. Tremor amplitude is logarithmically related to 4- and 5-point tremor rating scales. Brain. 2006;129:2660–2666. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl190. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Giuffrida JP, Riley DE, Maddux BN, Heldman DA. Clinically deployable Kinesia technology for automated tremor assessment. Mov Disord. 2009;24:723–730. doi: 10.1002/mds.22445. doi: 10.1002/mds.22445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cleeves L, Findley LJ. Variability in amplitude of untreated essential tremor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50:704–708. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.50.6.704. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.50.6.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elble RJ, Higgins C, Leffler K, Hughes L. Factors influencing the amplitude and frequency of essential tremor. Mov Disord. 1994;9:589–596. doi: 10.1002/mds.870090602. doi: 10.1002/mds.870090602. Erratum in: Mov Disord 1995;10:411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pulliam CL, Eichenseer SR, Goetz CG, et al. Continuous in-home monitoring of essential tremor. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20:37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.09.009. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goetz CG, Stebbins GT, Wolff D, et al. Testing objective measures of motor impairment in early Parkinson’s disease: feasibility study of an at-home testing device. Mov Disord. 2009;24:551–556. doi: 10.1002/mds.22379. doi: 10.1002/mds.22379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weir JP. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19:231–240. doi: 10.1519/15184.1. doi: 10.1519/00124278-200502000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elble R, Zesiewicz T. Fahn-Tolosa-Marin tremor scale and digitizing tablet have comparable minimum detectable change. Mov Disord. 2015;30:S558. doi: 10.7916/D89S20H7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Louis ED. More time with tremor: the experience of essential tremor versus Parkinson’s disease patients. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2016;3:36–42. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.12207. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.12207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spooner J, Dressing SA, Meals DW. Minimum detectable change analysis. Tech Notes 7, December 2011. Environmental Protection Agency. 2011 http://www.bae.ncsu.edu/programs/extension/wqg/319monitoring/tech_notes.htm: U.S.

- 55.Heldman DA, Espay AJ, LeWitt PA, Giuffrida JP. Clinician versus machine: reliability and responsiveness of motor endpoints in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20:590–595. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.02.022. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Randall JE. A stochastic time series model for hand tremor. J Appl Physiol. 1973;34:390–395. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1973.34.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]