Abstract

As viable precursors to a diverse array of macromolecules, biomass-derived compounds must impart wide-ranging and precisely controllable properties to polymers. Herein, we report the synthesis and subsequent reversible addition–fragmentation chain-transfer polymerization of a new monomer, syringyl methacrylate (SM, 2,6-dimethoxyphenyl methacrylate), that can facilitate widespread property manipulations in macromolecules. Homopolymers and heteropolymers synthesized from SM and related monomers have broadly tunable and highly controllable glass transition temperatures ranging from 114 to 205 °C and zero-shear viscosities ranging from ∼0.2 kPa·s to ∼17,000 kPa·s at 220 °C, with consistent thermal stabilities. The tailorability of these properties is facilitated by the controlled polymerization kinetics of SM and the fact that one vs two o-methoxy groups negligibly affect monomer reactivity. Moreover, syringol, the precursor to SM, is an abundant component of depolymerized hardwood (e.g., oak) and graminaceous (e.g., switchgrass) lignins, making SM a potentially sustainable and low-cost candidate for tailoring macromolecular properties.

To address sustainability challenges associated with petrochemicals, researchers are exploiting a plethora of renewable chemicals to generate biobased, cost-effective, and thermomechanically useful macromolecules.1−11 Lignin is one renewable resource that shows promise as a desirable alternative to petroleum feedstocks, largely due to its abundance as a byproduct of pulp and paper refining. Corresponding lignin-based bio-oils (e.g., the volatile fraction of pyrolyzed lignin) contain numerous aromatic compounds that structurally mimic common monomers (e.g., bisphenol A and styrene) for polymer applications.4−7 The exact structure and composition of a lignin-based bio-oil is highly variable, depending on the biomass resource (tree, crop residue, grass, etc.), lignin type (Kraft, Organosolv, etc.), and depolymerization route (enzymatic, catalytic, etc.), among other factors.12−17 In general, the native components of all lignin-based bio-oils include phenols and guaiacols (2-methoxyphenols), whereas the native components of angiosperm (hardwood—e.g., oak and maple tree) and graminaceous (grassy—e.g., switchgrass and corn stover) bio-oils also include syringols (2,6-dimethoxyphenols).12−14

Biobased compounds increasingly are being incorporated into thermoplastic elastomers (TPEs), pressure-sensitive adhesives, composite binders, and drug delivery vehicles,7−11 all systems that benefit from macromolecules prepared via controlled polymerization techniques. The synthesis methods, such as reversible addition–fragmentation chain-transfer (RAFT), anionic, or atom-transfer radical polymerization,18 are desirable for facilitating the generation of polymers (and block copolymers) with precise macromolecular characteristics through the control of kinetic parameters. For RAFT polymerizations, important parameters include the apparent propagation rate (kp,app, which describes monomer-to-polymer conversion rates) and the apparent chain-transfer coefficient (Ctr,app, which describes the consumption rate of chain-transfer agent [CTA] and the conversion-dependent change in polymer dispersity [Đ]). Kinetic parameters that are consistent, in addition to controllable, also facilitate comparisons of polymer properties due to the ease with which macromolecules of matching end-groups, molecular weights, and Đ’s can be prepared.

For the above applications, properties that are among the most indicative of material practicality are the glass transition temperature (Tg) and the zero-shear viscosity (η0). The Tg indicates the temperature at which a macromolecule transitions between glassy (solid-like) and rubbery (liquid-like) behavior, and the η0 describes how easily a material may deform at a given temperature. Polymers with a Tg near 100 °C are useful for boiling-water-stable plastics, and polymers with a Tg well above 100 °C are useful for high-temperature applications (e.g., machine parts and asphalt components). Ideally, one could access Tg’s anywhere from 100 to 200 °C via biobased monomers and controlled polymerizations; however, a dearth of examples is noted for high molecular weight macromolecules with Tg’s in the range of ≈135–190 °C,7 although some polymers come close.11,19,20 Furthermore, materials with η0’s of ∼10–100 Pa·s (e.g., condiments) are easily spread and shaped, and those with η0’s of ∼106–108 Pa·s (e.g., bitumen for roads) are highly deformation resistant. An ability to choose between these Tg’s and η0’s in a biobased macromolecule would be ideal for optimizing processability and mechanical strength in the pursuit of sustainable macromolecules prepared using controlled means.

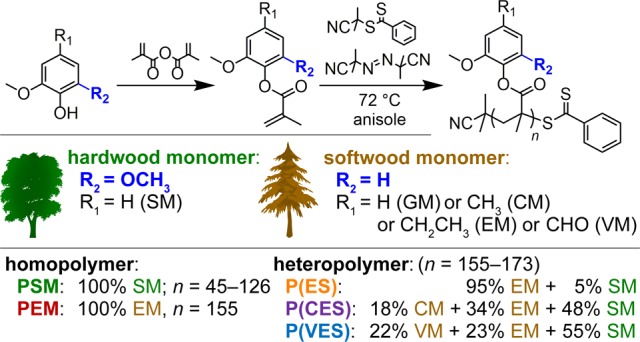

The major lignin-based bio-oil components that have been incorporated into controlled polymerizations are guaiacols with varying p-position R-groups, as shown in Scheme 1.21−23 The different functionalities (e.g., ethyl, methyl, formyl, and hydrogen R-groups) are seen as potential handles for modulating polymer properties,21−23 but the resulting macromolecules have a fairly narrow range of accessible properties. Specifically, poly(4-ethylguaiacyl methacrylate) (PEM) has the lowest Tg of ≈110 °C and η0 of 7 × 105 Pa·s at 150 °C, while poly(vanillin methacrylate) (PVM) has the highest Tg of ≈130 °C and η0 of 3 × 107 Pa·s at 150 °C.23 Although this range is useful for the fine-tuning of macromolecular properties, it does not lead to ultimate material versatility.23

Scheme 1. Synthesis Scheme, Nomenclature, Mass Compositions, and Degrees of Polymerization (n’s) of Lignin-Based Monomers and Polymers Reported Herein.

Herein, a syringol derivative, syringyl methacrylate (SM), is synthesized for the first time and incorporated into controlled polymerizations to greatly expand the window of Tg’s and η0’s accessible via biobased monomers. In fact, as shown below, the Tg for PSM is greater than that reported for almost any other amorphous polymer lacking cyclic groups in the backbone, yet the monomer is readily polymerizable, especially in comparison to other high-Tg phenyl methacrylates, such as 2,6-dimethylphenyl methacrylate. An additional advantage of the syringols in comparison to the guaiacols is the potential abundance of the former; syringols constitute anywhere from ∼40 wt % to 90 wt % of identified monophenolic compounds in fractions of thermally decomposed hardwood or grassy lignins,12 and ∼60 wt % of pulpwood worldwide comes from hardwood trees that contain syringylic components.24 These characteristics make syringols ideal biobased precursors to polymers.

Furthermore, heteropolymers (multicomponent polymers) containing SM segments are prepared in this study to show that properties of macromolecules can be widely manipulated via SM content, while also enabling greater usage of bio-oil fractions, consistent with biobased materials objectives.11,22,23,25−27 To this end, SM was incorporated into polymerizations of mixed softwood lignin-based monomers, viz., EM, VM, and creosyl methacrylate (CM), in which these components, the corresponding heteropolymers, and the macromolecules’ weight compositions are shown in Scheme 1. Poly(CM-co-EM-co-SM) [P(CES)] and poly(VM-co-EM-co-SM) [P(VES)] have compositions that approximately mimic the compositions reported for a bio-oil prepared from switchgrass Organosolv lignin12 [weight-fraction SM (fS) = 0.48 for P(CES) and 0.55 for P(VES)], and poly(EM-co-SM) [P(ES), fS = 0.05] has a composition that was chosen to show that small amounts of SM can be incorporated into a polymer and measurably change its properties.

SM, PSM, and SM-containing heteropolymers were synthesized successfully by employing procedures akin to those used for softwood lignin-based monomers and polymers28 (see Scheme 1 and also the Supporting Information). The successful synthesis and isolation of SM was somewhat unexpected, mainly because syringol tends to favor conversion to stable phenoxy radicals and colored quinones.29,30 The success of the SM RAFT polymerizations also was somewhat unexpected due to the o-methoxy groups; namely, other poly(phenyl methacrylate) derivatives with bulky o-groups can be challenging to synthesize due to low ceiling temperatures and polymer thermal stabilities.31,32

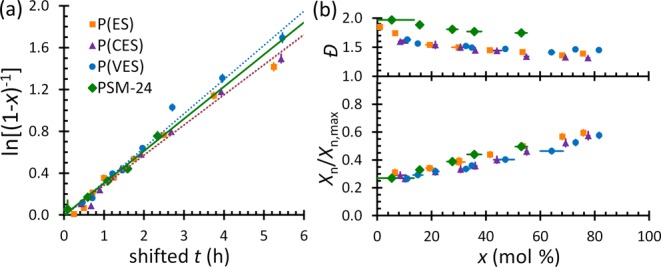

The polymerization rate and reactivity of SM are consistent with the polymerization rate and reactivity of softwood monomers (EM, CM, VM, and guaiacyl methacrylate [GM]),22 despite the hardwood monomer’s second o-position methoxy group. The kp,app’s, which are illustrated by the lines in Figure 1a for polymerizations performed under approximately identical reaction conditions, are the same at 95% confidence regardless of SM content and compare favorably to the kp,app’s previously reported for softwood monomers22 (kp,app = 0.25 ± 0.01 h–1 for PSM-2433 and 0.23–0.26 h–1 for SM-containing heteropolymers, vs 0.21–0.29 h–1 for guaiacylic polymers;22 exact values are listed in Table S2). The compositions of the monomer mixtures and the cumulative compositions of the heteropolymer chains also do not change measurably with respect to conversion [x] (see Figure S1), further indicating the similar reactivities of the hardwood and softwood monomers and the likely random distributions of monomer segments in each chain. Consequently, syringol and guaiacol contents in a mixture can be manipulated without harming the predictability of conversions, monomer distributions, and molecular weight.

Figure 1.

(a) Pseudo-first-order kinetic data, in which x is molar percent conversion and t is reaction time shifted by 0.02–0.24 h to a pre-equilibrium time of 0 h. The lines are the linearized fits used to estimate kp,app [lines for P(ES) and P(CES) are indistinguishable]. (b) Conversion-dependent molecular weight characteristics (Đ and normalized degree of polymerization, Xn/Xn,max) of polymers containing SM units. These data indicate the consistent RAFT polymerization characteristics of lignin-based polymers regardless of SM content.

Control over the RAFT polymerizations also is consistent between guaiacylic22 and syringylic monomers, simplifying the process of tailoring macromolecular characteristics. First, as shown by the data in Figure 1b, the Đ’s decrease with respect to increasing x, and the normalized degrees of polymerization (Xn/Xn,max’s) change linearly with x, indicating that the polymerizations are controlled. Second, the size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) data are unimodal (see Figure S2), and the Đ’s of the homopolymers and heteropolymers (1.32–1.74, see Table S1) are similar to or better than what was reported for PVMs that were successfully chain-extended to generate self-assembling block copolymers.21 Finally, the Đ’s and Xn/Xn,max’s for the homopolymers and heteropolymers change with respect to x in an approximately equivalent manner, albeit slightly shifted vertically due to differences in polymer solubility. The consistency of these data was confirmed by estimating the Ctr,app from the heteropolymerizations using the Mayo equation.22 The resulting Ctr,app’s for the heteropolymers were within error of values reported for the polymerizations of GM, EM, CM, VM, and corresponding mixtures (Ctr,app = 1.4–2.8 for softwood monomers and mixtures22 vs 2.3–3.0 for SM-containing mixtures, as listed in Table S2). Additionally, Ctr,app for SM homopolymerizations is approximately the same as for softwood monomer polymerizations,34 further supporting that the second o-methoxy group has a negligible effect on the polymerization behavior of lignin-based methacrylates.

PSM-24 has a high Đ in part because the reaction mixture gelled. Lower Đ’s listed in Table S1 have been achieved by diluting the reaction, reducing the target molecular weight, changing the solvent, and incorporating softwood lignin-based methacrylate monomers. All of these changes contribute to reductions in solution viscosity and thus Đ.35,36

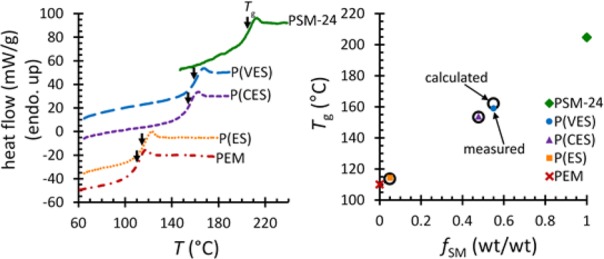

The measured Tg’s of the PSM homopolymers (185–205 °C depending on molecular weight, see also Table S1) are among the highest reported for amorphous, linear polymers with aliphatic backbones, even greater than the Tg’s reported for poly(2,6-dimethylphenyl methacrylate) (189 °C) and poly(2,6-diisopropylphenyl methacrylate) (198 °C).37 A PSM of infinite molecular weight could have a Tg as high as ≈220 °C, assuming Flory–Fox behavior when fitting data from Table S1. The Tg of PSM-24 is ≈75 °C higher than that of PVM and ≈95 °C higher than that of PEM at similar number-average molecular weight. The differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) data for PEM and SM-containing polymers are shown in Figure 2 for comparison.

Figure 2.

DSC data and the corresponding measured and calculated (via the Fox equation) Tg’s as a function of SM-content, which together show the wide-ranging and predictable Tg’s available through hardwood and softwood lignin-based methacrylates. DSC data were shifted vertically and normalized to a slope of zero at T > Tg for clarity. PEM data were reported previously.23

SM segments also can be incorporated into polymers to make predictable changes to the Tg based on composition and the Fox equation.38 The actual and calculated Fox-based Tg’s agree closely, as shown in Figure 2, in which the black circles (calculated Tg’s) overlay the colored shapes (measured Tg’s). For example, incorporating 5 wt % of SM segments into PEM raises the Tg by 4 °C (from 110 to 114 °C), the predicted increase. The heteropolymers with compositions that mimic possible fractions of bio-oil (fSM = 0.48–0.55) have similarly predictable, yet high (154 and 159 °C) Tg’s. Furthermore, the onset thermal degradation temperatures in air (see Table S2 and Figure S3) for PSM (303 ± 5 °C) and the heteropolymers (256–260 °C) are ≈100 °C greater than each of the measured Tg’s; thus, these polymers can be melt processed without significant thermal degradation.

The high Tg of PSM and its effectiveness for tailoring polymer Tg’s results more from differences in monomer structure than tacticity. PSM is somewhat more syndiotactic than the softwood lignin-based polymers (see Supporting Information for racemo diad and syndiotactic triad contents), yet the Tg differential between the hardwood and softwood monomers is far more significant than the differences reported for other atactic vs syndiotactic vs isotactic methacrylate polymers. The Tg increase between atactic and syndiotactic poly(methyl methacrylate) is 10 °C,39 and the Tg difference between isotactic and syndiotactic poly(phenyl methacrylate)s and poly(4-methoxyphenyl methacrylate)s is similarly small.40 Instead, the factor contributing most significantly to the Tg likely is the restricted rotational freedom of the side chain around the phenol–ester linkage, which arises from interactions between the carbonyl in the ester and bulky o-groups. This explanation is consistent with the rigidity argument previously applied to explain Tg differences between poly(phenyl methacrylates) with varying o-alkyl substituents.37,41

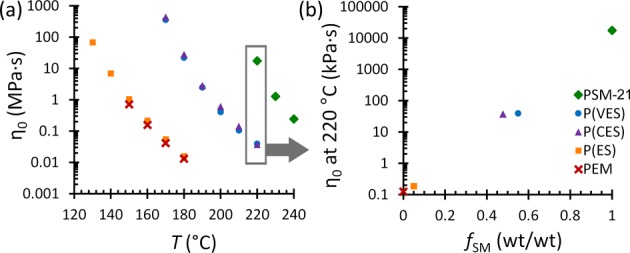

The η0’s for SM-containing polymers span ∼5 orders of magnitude and depend largely on the SM content. This promising range of deformation resistances accessible via lignin-based monomers is illustrated in Figure 3a (see also Figures S4 and S5 for related dynamic mechanical analysis data). For example, the η0 at 220 °C is 17,000 kPa·s for PSM and significantly less for the SM-containing heteropolymers (0.2–40 kPa·s), as shown in Figure 3b and listed in Table S2. This window of η0’s is substantial in comparison to the ∼2 orders of magnitude spanned by the complete range of guaiacylic methacrylate polymers23 and could be wider if higher molecular weight polymers, relative to PSM-24, were examined. Thus, SM provides a much wider space over which processability and deformation resistance can be optimized.

Figure 3.

Zero-shear viscosities (a) as a function of temperature and (b) as a function of SM content, which together show the wide-ranging η0’s available through hardwood and softwood LBMs. Data for PEM were reported previously.23

In summary, no other system of biobased monomers allows Tg’s from ≈100 °C (ideal for thermoformable yet boiling-water-stable plastics, such as cups) to ≈200 °C (ideal for heat- and flow-resistant materials, such as asphalt binders) to be accessed as readily as the lignin-based monomers presented herein. The measurable changes in Tg and η0 at small SM contents, and the wide-ranging thermomechanical properties reported for all of these polymers, indicate that SM could be a powerful add-in monomer for adjusting material properties. The similar polymerization characteristics between softwood and hardwood monomers also greatly simplify the task of predicting a priori macromolecular characteristics and properties of any heteropolymer containing syringylic segments. Hence, SM is an extraordinary new biobased monomer for its ability to significantly raise polymer Tg’s and deformation resistances at small added contents, so the isolation of syringol from hardwood or grassy lignin-based bio-oils and its conversion to SM has the potential to become a worthwhile investment.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge NSF grant CHE-1507010 to T.H.E. for supporting A.L.H., NSF grant DMR-1506623 to R.P.W. for supporting K.H.R., and UD’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering and NIST award 70NANB10H256 through the UD Center for Neutron Science for supporting N.A.N. The UD NMR facility was supported financially by the Delaware COBRE program with a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences – NIGMS (1 P30 GM110758-01) from the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank the UD Advanced Materials Characterization Lab for use of the DSC instrument and thermogravimetric analyzer; Michael G. Karavolias and John A. McCarron for synthesizing and purifying guaiacylic monomers; Prof. Michael E. Mackay for use of the rheometer; and Jacob P. Brutman and Prof. Marc A. Hillmyer at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities for the chloroform SEC data.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmacrolett.6b00270.

Experimental conditions and methods, macromolecular characteristics, table of heteropolymer properties, SEC data, composition vs conversion data, thermolysis data, and additional rheology data (PDF)

Author Present Address

¶ Department of Chemical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, United States.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Author Status

∥ Deceased: 24 March 2015

Supplementary Material

References

- Mathers R. T. How Well Can Renewable Resources Mimic Commodity Monomers and Polymers?. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2012, 50 (1), 1–15. 10.1002/pola.24939. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mülhaupt R. Green Polymer Chemistry and Bio-Based Plastics: Dreams and Reality. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2013, 214 (2), 159–174. 10.1002/macp.201200439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Isikgor F. H.; Becer C. R. Lignocellulosic Biomass: A Sustainable Platform for the Production of Bio-Based Chemicals and Polymers. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6 (25), 4497–4559. 10.1039/C5PY00263J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Llevot A.; Grau E.; Carlotti S.; Grelier S.; Cramail H. From Lignin-Derived Aromatic Compounds to Novel Biobased Polymers. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2016, 37 (1), 9–28. 10.1002/marc.201500474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delidovich I.; Hausoul P. J. C.; Deng L.; Pfützenreuter R.; Rose M.; Palkovits R. Alternative Monomers Based on Lignocellulose and Their Use for Polymer Production. Chem. Rev. 2015, 116, 1540. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandini A.; Lacerda T. M. From Monomers to Polymers from Renewable Resources: Recent Advances. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2015, 48, 1–39. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2014.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg A. L.; Reno K. H.; Wool R. P.; Epps T. H. III Biobased Building Blocks for the Rational Design of Renewable Block Polymers. Soft Matter 2014, 10 (38), 7405–7424. 10.1039/C4SM01220H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao K.; Tang C. Controlled Polymerization of Next-Generation Renewable Monomers and Beyond. Macromolecules 2013, 46 (5), 1689–1712. 10.1021/ma3019574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh K. Controlled/Living Polymerization of Renewable Vinyl Monomers into Bio-Based Polymers. Polym. J. 2015, 47 (8), 527–536. 10.1038/pj.2015.31. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hillmyer M. A.; Tolman W. B. Aliphatic Polyester Block Polymers: Renewable, Degradable, and Sustainable. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47 (8), 2390–2396. 10.1021/ar500121d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher J. J.; Hillmyer M. A.; Reineke T. M. Isosorbide-Based Polymethacrylates. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2015, 3 (4), 662–667. 10.1021/sc5008362. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.-Y.; Park J.; Hwang H.; Kim J. K.; Song I. K.; Choi J. W. Catalytic Depolymerization of Lignin Macromolecule to Alkylated Phenols over Various Metal Catalysts in Supercritical tert-Butanol. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2015, 113, 99–106. 10.1016/j.jaap.2014.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asmadi M.; Kawamoto H.; Saka S. Gas- and Solid/Liquid-Phase Reactions During Pyrolysis of Softwood and Hardwood Lignins. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2011, 92 (2), 417–425. 10.1016/j.jaap.2011.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buranov A. U.; Mazza G. Lignin in Straw of Herbaceous Crops. Ind. Crops Prod. 2008, 28 (3), 237–259. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2008.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ragauskas A. J.; Beckham G. T.; Biddy M. J.; Chandra R.; Chen F.; Davis M. F.; Davison B. H.; Dixon R. A.; Gilna P.; Keller M.; Langan P.; Naskar A. K.; Saddler J. N.; Tschaplinski T. J.; Tuskan G. A.; Wyman C. E. Lignin Valorization: Improving Lignin Processing in the Biorefinery. Science 2014, 344 (6185), 1246843. 10.1126/science.1246843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaujia P. K.; Sharma Y. K.; Garg M. O.; Tripathi D.; Singh R. Review of Analytical Strategies in the Production and Upgrading of Bio-Oils Derived from Lignocellulosic Biomass. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2014, 105, 55–74. 10.1016/j.jaap.2013.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C.; Arancon R. A. D.; Labidi J.; Luque R. Lignin Depolymerisation Strategies: Towards Valuable Chemicals and Fuels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43 (22), 7485–7500. 10.1039/C4CS00235K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates F. S.; Hillmyer M. A.; Lodge T. P.; Bates C. M.; Delaney K. T.; Fredrickson G. H. Multiblock Polymers: Panacea or Pandora’s Box?. Science 2012, 336 (6080), 434–440. 10.1126/science.1215368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosnáček J.; Matyjaszewski K. Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization of Tulipalin A: A Naturally Renewable Monomer. Macromolecules 2008, 41 (15), 5509–5511. 10.1021/ma8010813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J.; Lee Y.; Tolman W. B.; Hillmyer M. A. Thermoplastic Elastomers Derived from Menthide and Tulipalin A. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13 (11), 3833–3840. 10.1021/bm3012852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg A. L.; Stanzione J. F. III; Wool R. P.; Epps T. H. III A Facile Method for Generating Designer Block Copolymers from Functionalized Lignin Model Compounds. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2014, 2 (4), 569–573. 10.1021/sc400497a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg A. L.; Karavolias M. G.; Epps T. H. III RAFT Polymerization and Associated Reactivity Ratios of Methacrylate-Functionalized Mixed Bio-Oil Constituents. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6 (31), 5728–5739. 10.1039/C5PY00291E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg A. L.; Nguyen N. A.; Karavolias M. G.; Reno K. H.; Wool R. P.; Epps T. H. III Softwood Lignin-Based Methacrylate Polymers with Tunable Thermal and Viscoelastic Properties. Macromolecules 2016, 49 (4), 1286–1295. 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b02316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- FAO Yearbook of Forest Products 2013; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2015; pp 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Fache M.; Boutevin B.; Caillol S. Epoxy Thermosets from Model Mixtures of the Lignin-to-Vanillin Process. Green Chem. 2016, 18 (3), 712–725. 10.1039/C5GC01070E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanzione J. F. III; Giangiulio P. A.; Sadler J. M.; La Scala J. J.; Wool R. P. Lignin-Based Bio-Oil Mimic as Biobased Resin for Composite Applications. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2013, 1 (4), 419–426. 10.1021/sc3001492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Vajjala Kesava S.; Gomez E. D.; Robertson M. L. Sustainable Thermoplastic Elastomers Derived from Fatty Acids. Macromolecules 2013, 46 (18), 7202–7212. 10.1021/ma4011846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanzione J. F. III; Sadler J. M.; La Scala J. J.; Wool R. P. Lignin Model Compounds as Bio-Based Reactive Diluents for Liquid Molding Resins. ChemSusChem 2012, 5 (7), 1291–1297. 10.1002/cssc.201100687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steelink C. Stable Phenoxy Radicals Derived from Phenols Related to Lignin1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87 (9), 2056–2057. 10.1021/ja01087a041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altwicker E. R. The Chemistry of Stable Phenoxy Radicals. Chem. Rev. 1967, 67 (5), 475–531. 10.1021/cr60249a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otsu T.; Yamada B.; Sugiyama S.; Mori S. Effects of Ortho-Substituents on Reactivities, Tacticities, and Ceiling Temperatures of Radical Polymerizations of Phenyl Methacrylates. J. Polym. Sci., Polym. Chem. Ed. 1980, 18 (7), 2197–2207. 10.1002/pol.1980.170180715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada B.; Sugiyama S.; Mori S.; Otsu T. Low Ceiling Temperature in Radical Polymerization of 2,6-Dimethylphenyl Methacrylate. J. Macromol. Sci., Chem. 1981, 15 (2), 339–345. 10.1080/00222338108066450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The hyphenated value following a homopolymer designation corresponds to that material’s number-average molecular weight listed in Table S1.

- A similar evaluation of Ctr,app was not made for PSM due to the unsuitability of comparing Đ data taken using different instrumentation and solvents. In this case, SEC data for PSM were collected in chloroform instead of tetrahydrofuran (the eluent for the other polymers) due to solubility issues.

- Trommsdorff V. E.; Köhle H.; Lagally P. Zur Polymerisation Des Methacrylsäuremethylesters. Makromol. Chem. 1948, 1 (3), 169–198. 10.1002/macp.1948.020010301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norrish R. G. W.; Smith R. R. Catalysed Polymerization of Methyl Methacrylate in the Liquid Phase. Nature 1942, 150, 336–337. 10.1038/150336a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gargallo L.; Hamidi N.; Radić D. Effect of the Side Chain Structure on the Glass Transition Temperature: 2. Poly(o-Alkylphenyl Methacrylate)s. Thermochim. Acta 1987, 114 (2), 319–328. 10.1016/0040-6031(87)80054-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox T. G. Influence of Diluent and of Copolymer Composition on the Glass Temperature of a Polymer System. Bull. Am. Phys. Soc. 1956, 1, 123. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly J. M.; Bair H. E.; Karasz F. E. Thermodynamic Properties of Stereoregular Poly(Methyl Methacrylate). Macromolecules 1982, 15 (4), 1083–1088. 10.1021/ma00232a024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wesslén B.; Gunneby G.; Hellström G.; Svedling P. Synthesis and Characterization of Poly (Phenyl Methacrylates). J. Polym. Sci., Polym. Symp. 1973, 42 (1), 457–465. 10.1002/polc.5070420152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gargallo L.; Hamidi N.; Radić D. Synthesis, Solution Properties and Chain Flexibility of Poly(2,6-Dimethylphenyl Methacrylate). Polymer 1990, 31 (5), 924–927. 10.1016/0032-3861(90)90057-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.