Youth Suicide as a Public Health Issue in Hawai‘i

Youth suicide is a serious, yet preventable public health problem. The US suicide rate has more than doubled among youth since 1950,1 but has remained relatively stable over the last few decades.2 In Hawai‘i, an average of one suicide occurs every two days, with suicide being the leading cause of injury-related death among 15–24 year olds.3 Furthermore, compared to national averages, Hawai‘i's youth are more likely to report that they have seriously considered attempting suicide, made a suicide plan, and attempted suicide.4 Although suicide was once a rare occurrence in Hawai‘i, suicide rates among Native Hawaiians have been increasing since the state of Hawai‘i began collecting suicide statistics in 1908.5 Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) adolescents are now among the highest risk for suicide-related behaviors in the United States.5–7 Despite these health disparities, there are many strengths and resources that reside in Hawai‘i's NHPI communities, with youth reporting that they receive a tremendous amount of informal support from community members.8

Those living in rural communities also have higher rates of suicide and suicide attempts compared to urban residents.9,10 All five inhabited islands outside of metropolitan Honolulu, as well as specific areas of O‘ahu, are considered rural and federally designated as Health Professional Shortage Areas and Medically Underserved Populations.11 Rural youth in Hawai‘i are nearly four times more likely than urban youth to use the emergency department for mental health care.12 However, as with the ethnic groups discussed above, rural communities have strong social connections and are willing to come together on common concerns.13 Therefore, suicide prevention programs that address ethnic and geographic disparities, as well as the unique strengths and resources in these communities are needed. This paper describes the youth-led community awareness efforts for youth suicide prevention that were implemented in Hawai‘i's rural communities and provides examples of how these efforts integrated safe messaging guidelines.

Hawai‘i's Caring Communities Initiative for Youth Suicide Prevention

In 2011, the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa, John A. Burns School of Medicine was awarded a three-year Garret Lee Smith grant for youth suicide prevention from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Through this grant, the Hawai‘i's Caring Communities Initiative (HCCI) was created with a mission of preventing youth suicide by partnering with youth-serving community organizations,14 emergency departments, and critical access hospitals.15 The community partners and emergency departments received training through the Connect Suicide Prevention Training Program, which is an evidence-based program developed by New Hampshire's National Alliance on Mental Illness.16 Using a combination of PowerPoint slides, interactive exercises, and case scenarios, the Connect Program uses a socioecological model to enhance participants' abilities to recognize warning signs of suicide risk, increase their comfort level in making connections with youth, promote knowledge of risk and protective factors, and reduce stigma around mental health issues. It also seeks to increase coordination and communication across organizations working in the area of youth suicide prevention and response efforts by providing a common language of suicide prevention-related terms and concepts. The Connect Program is responsive to the target community's needs and strengths by allowing for cultural tailoring while adhering to evidence-based practices in suicide prevention,17 which is an important factor in promoting mental wellness among minority and indigenous youth.18

Community-based suicide prevention awareness campaigns have been shown to be an effective strategy to reduce suicide and increase awareness.19,20 Therefore, HCCI worked directly with community organizations in six rural communities across the state of Hawai‘i that have high proportions of NHPIs, including Kahuku and Waimanalo on O‘ahu, Hilo on Hawai‘i Island, Kahului on Maui, Kaua‘i, and Moloka‘i.21 One or two staff members from each organization was selected to serve as the Community Coordinator for HCCI. They participated in an intensive three-day Connect Training Program and were certified as Connect community trainers. The Community Coordinators then recruited youth from their community and trained them on suicide prevention using the Connect Program. Over the course of the grant, the Community Coordinators and the HCCI staff worked closely together to empower the youth to be youth leaders in suicide prevention. With the guidance of the Community Coordinators, the youth provided suicide prevention trainings to their peers and community members as well as developed and implemented suicide prevention awareness campaigns and events that adhered to safe messaging guidelines.14

Safe Messaging Guidelines for Suicide Prevention

Safe messaging is an important concept when developing community awareness campaigns and events related to suicide prevention.22 Studies show that when a suicide is highly publicized and described in details, the potential for “copycat” suicides increases, particularly among youth.23 The magnitude of the increase in suicides following a suicide story is proportional to the amount, duration, and prominence of media.24 For example, a review of 293 findings from 42 studies found that media coverage of suicide deaths of celebrity or political figures increase that likelihood of a copycat effect by 14.3 times.25 In response, safe messaging guidelines have been developed to ensure that public messages about suicide do not unintentionally increase suicide risk for vulnerable individuals who are receiving the messages. These guidelines can be applied to community awareness campaigns and educational and training efforts for suicide prevention for the general public (see Table 1).26

Table 1.

Safe and Effective Messaging for Suicide Prevention26

| Recommendations for public awareness campaigns: | |

| The Do's | The Don'ts |

|

|

In addition, community-based public awareness campaigns offer survivors of suicide attempts and those who have lost someone to suicide a space to tell their stories, as a way for them to share with the community, to heal, and to put a face to the issue of suicide. Safe messaging should also be applied in these storytelling activities. Safe messaging for survivor speakers includes ensuring the speaker is at a point in their healing process where the focus is on what can be done to make things better in the future, and offer a message of hope to the audience.27 In addition, graphic details of the death should not be shared. It is also important to ensure that the speaker is provided a non-judgmental and compassionate space where the audience has an understanding of mental health. Moreover, “resource people” who are trained to provide resources and emotional support for anyone who might have an emotional reaction to the topic, should be present at all suicide prevention trainings and events.

Although the importance of safe messaging is widely accepted, there are limited resources to train youth and community members to translate and apply these concepts to their community awareness efforts. Thus, the HCCI team developed a safe messaging training using a PowerPoint presentation as well as interactive exercises to show some of the most common examples of unsafe messaging in the media and encourage youth to critically think about the safety of various community awareness ideas. The training emphasized the need to understand the audience and tailor messages to their context while ensuring the safety of the recipients. For example, trainees were taught to avoid data that normalizes or sensationalizes suicide or display pictures of suicide methods (ie, guns, ropes, etc). The use of positive messages that instill hope, resiliency, and healing was also encouraged.

As the youth developed ideas for their community awareness campaigns, the HCCI team provided continuous feedback to ensure their activities and messages adhered to safe messaging guidelines. These conversations were facilitated by the relationships and trust that the HCCI staff built with the communities, which is essential to working in NHPI communities.28 Knowing that face-to-face interactions were essential in building the relationship and trust, the HCCI staff members made numerous air flights to reach geographically dispersed areas across the state. In addition, retreats and webinars were organized to bring the youth leaders groups together to share challenges and ideas with one another.

Prior to receiving the safe messaging training, the youth leaders tended to be drawn to unsafe ideas for community awareness activities that included student assemblies with a large number of people and events that would memorialize people who have died by suicide and used sensational images of suicide methods. Once the youth leaders received the safe messaging training, and engaged in conversations with Community Coordinators and HCCI staff, they began to understand and actively apply the safe messaging guidelines to their community awareness campaign ideas. Examples from three communities that HCCI partnered with are described to illustrate how safe messaging guidelines were incorporated into youth-led community awareness campaigns.

Examples of youth-led suicide prevention awareness campaigns

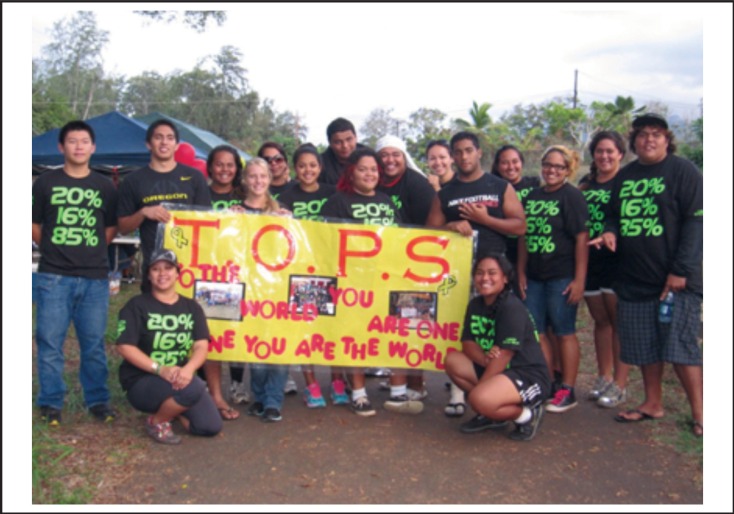

Teens on Preventing Suicide (TOPS) was created in the Kahuku community on O‘ahu (Figure 1). The TOPS youth leaders were concerned by the statistics on youth suicide behaviors from Hawai‘i's Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) and wanted to use these statistics as the basis for educating the public about the importance of youth suicide prevention. They decided to design t-shirts that featured the percentages of Hawai‘i's youth who had ever considered suicide (20%) and made a suicide plan (16%).4 They also included another statistic they learned during their training, which was that 85% of youth considering suicide will tell someone.29 This was done to emphasize the hopeful message that there is an opportunity to intervene. To reinforce the positive message, the back of the shirt displayed “100% Care.” This was the main message of their campaign, which was that the community cares about its members. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline number (1-800-273-TALK) was also provided on the sleeve of the shirt. The target audience for these shirts was the general community. However, the youth leaders also organized events such as a community walk and a school awareness activity where they developed resource materials for the audience. The TOPS youth leaders wore their t-shirts at all these events, which was immediately recognized by the community. The youth leaders and Community Coordinators reported that the t-shirts created a sense of intrigue among community members and often initiated a positive conversation about suicide prevention, thus decreasing the stigma that is typically associated with this topic.

Figure 1.

The TOPS youth leaders of Kahuku at their community walk for suicide prevention

Two youth groups were formed in Hilo, which were OLA (which means “life” in Hawaiian) and SPA (Suicide Prevention Awareness). Similar to the TOPS youth leaders, the OLA youth leaders also created a t-shirt campaign that integrated a hopeful life-affirming image. They also participated in various advocacy efforts in the community including sign-waving campaigns with the police department and proclamation signing for Suicide Prevention Week with the Mayor of Hilo. These efforts led to funding being provided for the youth leaders to participate in various suicide prevention trainings and conferences around the State. The SPA youth leaders conducted a self-care wellness fair at their school, where they distributed positive messages that promoted help-seeking behaviors and suicide prevention information and resources, including the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline number.

Maui Economic Opportunity's youth suicide prevention leaders, M.A.U. I. (Making An Unforgettable Impact) Kanak-tion, hosted two community awareness events in Kahului. Youth wanted to raise awareness about youth suicide while sharing information on the warning signs and following safe messaging guidelines. The events also focused on the importance of taking care of oneself and promoted hopeful messages around mental wellness. Their first event, a Care-nival, included a variety of game booths where participants could learn more about suicide prevention. Youth leaders also identified myths and facts about suicide prevention to share at each booth. In their second event, GLOW (Go Lighten Our World), they highlighted the struggles of dealing with suicide by creating an obstacle course. Participants engaged in role plays that promoted help-seeking behaviors and allowed them to practice how they could appropriately and compassionately respond to someone who may need mental health support. At both events, they provided the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline number on wallet cards with warning signs, and lists of local resources.

There are many more examples of youth-driven suicide prevention awareness activities that are published elsewhere. For instance, youth leaders from Kauai named Kaua‘i Leaders Against Suicide (KLAS) conducted a series of community awareness activities, including a radio public service announcement.14 Youth leaders from Moloka‘i named Suicide Prevention Across Moloka‘i (SPAM) also conducted community events that integrated the strengths and cultural traditions of their tight-knit community.30

Community Impact and Future Directions

During HCCI's three-year project period, the six youth leader groups developed and implemented a total of 31 community awareness activities. By counting the number of people in attendance at their events and estimating media readership and listenership, it is estimated that these youth-led awareness activities have reached over 643,000 people throughout the state of Hawai‘i. Efforts are currently underway to evaluate the impacts of these activities on suicide risk and stigma reduction. Although the funding for HCCI has officially ended, the partnerships created by HCCI have led to a series of collaborative efforts across the State to coordinate and sustain youth engagement and leadership in suicide prevention. For example, a Youth Leadership Council has been formed, which not only includes members from the original six communities that HCCI worked with, but also includes youth from other communities who have been touched by the HCCI community awareness activities. This Council provides a youth voice to the statewide Prevent Suicide Hawai‘i Task Force to inform policy, research, and community awareness activities. In addition, the Council youth leaders engage in ongoing training in suicide prevention and mental health as well as serve as advocates for community awareness.34,35

Increasing the awareness of youth suicide prevention as a public health concern is important to advance the overall wellness of our communities. Engaging youth as active partners in youth suicide prevention activities is promising because youth serve as important role models for their peers.31 However, these efforts must be cognizant of and align with safe messaging guidelines to avoid the possibility of unintentionally increasing the risk of suicide for those who may be facing mental health challenges. Resources for applying safe messaging guidelines for all types of communications about suicide, such as educational materials for the public, social media, newsletters, website content, event publicity, and public talks are growing, but more are needed. For example, the Framework for Successful Messaging by the Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention provides guidance to strategically promote hope, offer help, and increase resilience via all public messaging about suicide in a safe way.33 The HCCI project demonstrates that program implementation can be youth-driven while adhering to evidence-based practices of suicide prevention. Using a youth leadership model may enhance prevention strategies to address persistent health disparities in minority communities.32

Acknowledgements

Mahalo to the youth leaders, community partners, and university staff of the Hawai‘i's Caring Communities Initiative for their dedication to suicide prevention and mental wellness. Special thanks to Dynaka Merino and Annette Valjorma-Hunter for their inspiring work with the TOPS youth leaders. This manuscript was developed, in part, under grant number 1U79SM060394 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The views, opinions and content of this publication are those of the authors and contributors, and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of CMHS, SAMHSA, and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and should not be construed as such.

Contributor Information

Tetine L Sentell, Office of Public Health Studies at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa.

Donald Hayes, Hawai‘i Department of Health.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], author 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action. Washington, DC: DHHS; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Public Health Service, author. The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent Suicide. Washington, DC: DHHS; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galanis D. Overview of Suicides in Hawai‘i. Presented at: Statewide Prevent Suicide Hawai‘i Task Force meeting. Honolulu, Hawai‘i: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, author. Youth Online: High School YRBS. [April 6, 2016]. http://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/App/Default.aspx.

- 5.Else IRN, Andrade NN, Nahulu, LB. Suicide and suicidal-related behaviors among indigenous Pacific Islanders in the United States. Death Stud. 2007;31(5):479–501. doi: 10.1080/07481180701244595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuen NY, Nahulu LB, Hishinuma ES, Miyamoto RH. Cultural identification and attempted suicide in Native Hawaiian adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(3):360–370. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200003000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong SS, Sugimoto-Matsuda JJ, Chang JY, Hishinuma ES. Ethnic differences in risk factors for suicide among American high school students, 2009: The vulnerability of multiracial and Pacific Islander adolescents. Arch Suicide Res. 2012;16(2):159–173. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2012.667334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medeiros SM, Tibbetts KA. Ho'omau i nā ‘Ōpio: Findings from the 2008 pilot-test of the youth development and assets survey. Honolulu, HI: Kamehameha Schools Research and Evaluation Division; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirsch JK. A review of the literature on rural suicide: risk and protective factors, incidence, and prevention. Crisis. 2006;27(4):189–199. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.27.4.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, author. Nonfatal self-inflicted injuries treated in hospital emergency departments: United States, 2000. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2002;51(20):436–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawai‘i Primary Care Association, author. Hawai‘i Primary Care Directory: A directory of safety net health services in Hawai‘i. [April 8, 2016]. http://www.hawaiipca.net/media/assets/PrimaryCareDirectory2006.pdf.

- 12.Matsu C, Goebert D, Chung-Do J, Carlton B, Sugimoto-Matsuda J, Nishimura S. Disparities in psychiatric emergency department visits among youth in Hawai‘i, 2000 to 2010. J Pediatr. 2013;162(30):618–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berkes F, Ross H. Community resilience: Toward an integrated approach. Soc Nat Resour. 2013;26(1):5–20. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung-Do JJ, Goebert DA, Bifulco K, Tydingco T, Alvarez A, Rehuher D, Sugimoto-Matsuda J, Arume B, Wilcox P. Hawai‘i's Caring Communities Initiative: Mobilizing Rural and Ethnic Minority Communities for Youth Suicide Prevention. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2015;8(4):108–123. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugimoto-Matsuda J, Rehuher D. Suicide prevention in diverse populations: a systems and readiness approach for emergency settings. [April 8, 2016];Psychiatric Times. 2014 http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/cultural-psychiatry/suicide-prevention-diverse-populations-systems-and-readiness-approach-emergency-settings. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bean G, Baber KM. Connect: An effective community-based youth suicide prevention program. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2011;41(1):87–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2010.00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung-Do J, Bifulco K, Antonio M, Tydingco T, Helm S, Goebert D. A Cultural Analysis of the NAMI-NH Connect Suicide Prevention Program by Rural Community Leaders in Hawai‘i. J Rural Ment Health. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antonio M, Chung-Do, J. Systematic review of interventions focusing on Indigenous adolescent mental health and substance use. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2015;22(3):36–56. doi: 10.5820/aian.2203.2015.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Census Bureau, author. State and County Quick Facts. [April 8, 2016]. http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/15.

- 20.Oliver RJ, Spilsbury JC, Osiecki SS, Denihan WM, Zureick JL, Friedman S. Brief report: preliminary results of a suicide awareness mass media campaign in Cuyahoga County, Ohio. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008;38(2):245–249. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenner E, Jenner LW, Matthews-Sterling M, Butts JK, Williams TE. Awareness effects of a youth suicide prevention media campaign in Louisiana. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2010;40(4):394–406. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.4.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Etzersdorfer E, Sonneck G. Preventing suicide by influencing mass-media reporting. The Viennese experience 1980–1996. Arch Suicide Res. 1998;4(1):67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zenere FJ. Suicide clusters and contagion. Principal Leadership. 2009;10(2):12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gould MS. Suicide and the media. Ann N Y Acad Svi. 2001;932:200–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stack S. Media coverage as a risk factor in suicide. Public health policy and practice. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:238–240. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.4.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suicide Prevention Resource Center, author. Safe and Effective Messaging for Suicide Prevention. [April 8, 2016]. http://www.ct.gov/dmhas/lib/dmhas/prevention/cyspi/safemessaging.pdf.

- 27.Connect, author. Telling your own story: best practices for presentations by suicide loss and suicide attempt survivors. [April 8, 2016]. http://theconnectprogram.org/survivors/telling-your-own-story-best-practices-presentations-suicide-loss-and-suicide-attempt.

- 28.Chung-Do J, Look M, Mabello T, Trask-Batti M, Burke K, Mala Mau MKL. Engaging Pacific Islanders in research: community recommendations. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2016;10(1):63–71. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2016.0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juhnke GA, Granello PF, Granello DH. Suicide, self-injury, and violence in the schools: assessment, prevention, and intervention strategies. Honoken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung-Do JJ, Napoli SB, Hooper K, Tydingco T, Bifulco K. Youth-led suicide prevention in an indigenous rural community. [April 8, 2016];Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/cultural-psychiatry/youth-led-suicide-prevention-indigenous-rural-community. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antonio MA, Chung-Do J, Goebert D, Bifulco K, Tydingco T, Helm S. A Strength-Based and Youth-Driven Approach to Suicide Prevention in Rural and Minority Communities; Symposium presented at: Society for Prevention Research Conference; May 2015; Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guerra NG, Bradshaw CP. Linking the prevention of problem behaviors and positive youth development: Core competencies for positive youth development and risk prevention. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2008;122:1–17. doi: 10.1002/cd.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, Action Alliance Framework for Successful Messaging. [April 2016]. http://suicidepreventionmessaging.actionallianceforsuicideprevention.org/

- 34.Terrell J. 1 in 8 Hawaii Middle Schoolers Say They've Attempted Suicide. Civil Beat. [April 2016]. http://www.civilbeat.com/2016/04/1-in-8-hawaii-middle-schoolers-say-theyve-attempted-suicide/

- 35.Fujii N. How these Hawai‘i Youth Work to Prevent Suicide. Ka Leo. [April 2016]. http://www.kaleo.org/news/how-these-hawai-i-youth-work-to-prevent-suicide/article_e23c18ec-f527-11e5-b735-6754f5a6ff03.html.