Abstract

Background

Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides key biomarkers to predict onset and track progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, most published reports of relationships between MRI variables and cognition in older adults include racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically homogenous samples. Racial/ethnic differences in MRI variables and cognitive performance, as well as health, socioeconomic status and psychological factors, raise the possibility that brain-behavior relationships may be stronger or weaker in different groups. The current study tested whether MRI predictors of cognition differ in African Americans and Hispanics, compared with non-Hispanic Whites.

Methods

Participants were 638 non-demented older adults (29% non-Hispanic White, 36% African American, 35% Hispanic) in the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project. Composite scores of memory, language, speed/executive functioning, and visuospatial function were derived from a neuropsychological battery. Hippocampal volume, regional cortical thickness, infarcts, and white matter hyperintensity (WMH) volumes were quantified with FreeSurfer and in-house developed procedures. Multiple-group regression analysis, in which each cognitive composite score was regressed onto MRI variables, demographics, and cardiovascular health, tested which paths differed across groups.

Results

Larger WMH volume was associated with worse language and speed/executive functioning among African Americans, but not among non-Hispanic Whites. Larger hippocampal volume was more strongly associated with better memory among non-Hispanic Whites compared with Hispanics. Cortical thickness and infarcts were similarly associated with cognition across groups.

Conclusion

The main finding of this study was that certain MRI predictors of cognition differed across racial/ethnic groups. These results highlight the critical need for more diverse samples in the study of cognitive aging, as the type and relation of neurobiological substrates of cognitive functioning may be different for different groups.

Introduction

Quantitative measurement of brain structure, frequently undertaken with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), provides a key set of biomarkers to predict onset and track progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).[1] However, much of what is known about the relationship between structural MRI variables and cognitive performance comes from studies of racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically homogenous samples of older adults. For example, the 2012 demographic report from the landmark Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) describes the sample as comprising less than 5% African American participants, less than 3% Hispanic participants, and less than 20% participants who did not complete at least one year of college.[2] This publically-available dataset has contributed hundreds of publications to the knowledge base of neuroimaging markers in AD, yet it does not represent the demographic, cultural, or experiential diversity of the aging U.S. population. U.S. Census data from 2012–2013 indicate that the current population of Americans aged 65 and over comprises 9% Blacks, 7% Hispanics, and 52% of elders with less than one year of college.[3–5] Importantly, the projected population of Americans aged 65 and over in 2050 will comprise 12% Blacks and 20% Hispanics.[6]

It is important to study structural MRI predictors of cognitive functioning in more diverse populations not only to ensure generalizability of findings, but also to investigate potential differences in the causes and correlates of cognitive impairment across racial/ethnic groups. Such investigations may improve our understanding of racial/ethnic disparities in dementia incidence.[7–8] An early study from our northern Manhattan cohort found that the incidence of AD among adults aged 65 and older followed over seven years was 5.4% in non-Hispanic Whites, 10.5% in African Americans, and 9.8% in Hispanics.[7] Interestingly, risk factors for AD appear to differ across racial/ethnic groups. For example, studies of multiple cohorts suggest that the presence of an APOE-ε4 allele is a stronger determinant of AD risk among non-Hispanic Whites, compared with both African Americans and Hispanics.[9–11] Such findings, combined with evidence of differences in brain structural integrity, cognitive performance, health, educational quality, socioeconomic status and psychological factors, raise the possibility that the underlying neurobiological pathways to AD differ across racial/ethnic groups.

The goal of this study was to determine whether structural MRI predictors of performance in multiple cognitive domains differ across African American, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic White older adults who participated in a large epidemiological study in northern Manhattan. The four MRI variables were chosen because each has been shown to relate to cognitive performance in older adults: white matter hyperintensity (WMH) volume,[12] infarcts,[13–14] hippocampal volume,[12,15] and cortical thickness in “AD signature” regions.[16] Multiple cognitive domains are examined based on evidence that the neurobiological substrates of cognitive performance differ across cognitive domains.[17–18]

Material and Methods

Participants

The 638 older adults in this sample participated in the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP), a prospective, community-based longitudinal study of aging and dementia in northern Manhattan. Full descriptions of study procedures and the larger WHICAP sample have been published previously.[9,19] In brief, participants were identified from among Medicare-eligible residents of the geographic region of northern Manhattan in two initial recruitment waves (1992 and 1999) and followed at approximate 24-month intervals.

Beginning in 2005, 769 active WHICAP participants who were classified as non-demented at their previous study visit received structural MRI. On average, these participants were one year younger than those who refused MRI but were similar in terms of other characteristics.[20] The subset of 638 participants included in the present study met the following inclusion criteria: (1) underwent at least partial neuropsychological evaluation at the time of their MRI, (2) did not meet criteria for dementia based on this neuropsychological evaluation, (3) self-reported their race/ethnicity as White (non-Hispanic), African American (non-Hispanic) or Hispanic (any race), (4) had complete data on all covariates (i.e., age, sex, education, cardiovascular health), (5) had complete data on quantitative MRI variables of interest (i.e., WMH volume, presence of at least one infarct, intracranial volume-corrected hippocampal volume, and cortical thickness). Participants were not excluded for the presence of mild cognitive impairment. Characteristics of the sample at the time of the MRI scan are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics at baseline

| Entire sample (N=638) |

Non-Hispanic White (N=184) |

African American (N=229) |

Hispanic (N=225) |

Group differencesa |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 80.03 (5.60) | 80.16 (5.75) | 79.76 (5.74) | 80.18 (5.22) | W=AA=H |

| Education | 10.80 (4.77) | 13.68 (3.24) | 12.34 (3.44) | 6.88 (4.39) | W>AA>H |

| % Female | 68.18 | 59.78 | 69.00 | 74.22 | W<AA<H |

| CV risk | 1.10 (0.83) | 0.97 (0.82) | 1.19 (0.84) | 1.12 (0.81) | W<AA=H |

| % with Diabetes | 21.79 | 14.67 | 26.64 | 22.67 | W<AA=H |

| % with Hypertension | 66.61 | 55.98 | 69.43 | 72.44 | W<AA=H |

| % with Heart disease | 21.47 | 26.09 | 22.71 | 16.44 | W>H=AA |

| WMH volume | 3.51 (5.57) | 2.11 (3.13) | 4.89 (7.27) | 3.25 (4.79) | W<H<AA |

| % with Infarct(s) | 31.50 | 32.07 | 35.37 | 27.11 | W=AA=H |

| Hippocampal volume | 2.63 (0.38) | 2.55 (0.38) | 2.64 (0.39) | 2.69 (0.36) | W<AA=H |

| Cortical thickness | 2.58 (0.13) | 2.58 (0.12) | 2.55 (0.14) | 2.59 (0.13) | W=H>AA |

| Memory | 0.13 (0.73) | 0.36 (0.77) | 0.00 (0.79) | 0.07 (0.58) | W>AA=H |

| Language | 0.31 (0.64) | 0.65 (0.59) | 0.33 (0.56) | 0.02 (0.60) | W>AA>H |

| Speed/executive functioning | 0.18 (1.03) | 0.54 (0.82) | 0.32 (0.95) | −0.31 (1.12) | W>AA>H |

| Visuospatial | 0.30 (0.57) | 0.63 (0.38) | 0.33 (0.50) | 0.01 (0.63) | W>AA>H |

Note. CV=Cardiovascular; WMH=White Matter Hyperintensity; W=Non-Hispanic White; AA=African American; H=Hispanic

Group differences are based on t-tests (p<.05).

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance images were obtained on a 1.5T Philips Intera scanner at Columbia University Medical Center between 2005 and 2007. T1-weighted (repetition time = 20 ms, echo time = 2.1 ms, field of view 240 cm, 256 × 160 matrix, 1.3 mm slice thickness) and T2-weighted fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR; repetition time = 11,000 ms, echo time = 144.0 ms, inversion time = 2800, field of view 25 cm, 2 nex, 256 × 192 matrix with 3 mm slice thickness) images were acquired in the axial orientation.

White Matter Hyperintensities

Using previously-described procedures,[21–23] whole-brain WMH volumes were quantified from T2-weighted fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images. In brief, images were skull stripped, and a Gaussian curve was fit to map voxel intensity values. Voxels at least 2.0 standard deviations above the image mean were labeled as WMH. Labeled images were also visually inspected and corrected if errors were detected.

Infarcts

Infarcts were identified radiologically, as previously described.[24] In brief, all available images (e.g., T1-weighted, FLAIR, proton density, T2-weighted double-echo) were inspected for infarcts, defined as lesions 3 mm or larger. Infarcts were quantified by two raters, whose published κ values range from 0.73 to 0.90.[25]

Hippocampal Volume

Uncorrected hippocampal volume and total intracranial volume (ICV) were quantified with FreeSurfer version 5.1 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/) using T1-weighted images. Hippocampal volumes were corrected for intracranial volume before inclusion in all descriptive and inferential statistics. Corrected hippocampal volumes were computed as (FreeSurfer-derived hippocampal volume / FreeSurfer-derived ICV) × 1,000.

Cortical Thickness Composite

Regional cortical thickness was quantified with FreeSurfer version 5.1 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/) using T1-weighted images. A single “AD signature” measure was derived for each participant by averaging cortical thickness values across hemisphere in nine regions that have previously been shown to best reflect AD neurodegeneration.[16] These regions, named by Dickerson and colleagues and represented by FreeSurfer (in parentheses), included: rostral medial temporal lobe (entorhinal cortex and parahippocampus), angular gyrus (inferior parietal lobe), inferior frontal lobe (pars opercularis, pars orbitalis, and pars triangularis), inferior temporal lobe (inferior temporal lobe), temporal pole (temporal pole), precuneus (precuneus), supramarginal gyrus (supramarginal gyrus), superior parietal lobe (superior parietal lobe), and superior frontal lobe (superior frontal lobe).

Neuropsychological evaluation and dementia diagnosis

Participants in WHICAP are interviewed and tested in their preferred language (English or Spanish). Factor analysis has shown that the WHICAP neuropsychological battery measures four distinct cognitive domains (i.e., memory, language, speed/executive functioning, and visuospatial functioning) that are invariant across English and Spanish speakers.[26] Memory measures include total immediate recall, delayed recall, and delayed recognition scores from the Selective Reminding Test.[27] Language measures include naming, letter and category fluency, verbal abstraction, repetition, and comprehension. Speed/executive functioning measures include both trials of the Color Trails Test. Visuospatial tests include recognition and matching trials from the Benton Visual Retention Test,[28] visual abstraction, and the Rosen drawing test.[29] To compute composites, raw scores were converted to z-scores using means and standard deviations from the first study visit (either 1992 or 1999) in the larger WHICAP sample, then z-scores were averaged within domains. Scores are not corrected for demographic data.

After each visit, dementia diagnoses are made by consensus of neurologists and neuropsychologists based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised Third Edition criteria[30] using all available neuropsychological and interview data. Structural MRI data are not used for consensus diagnoses.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics and group comparisons (e.g., chi square tests, analyses of variance, and independent samples t-tests) were obtained using SPSS 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Regression analyses were conducted in Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA). Separate models were run for each of the four cognitive variables: memory, language, speed/executive functioning, and visuospatial. In initial models, a cognitive composite was regressed onto the four MRI variables (i.e., WMH volume, infarcts, hippocampal volume, cortical thickness) and demographic covariates (i.e., age, sex, education) simultaneously in the whole group. Follow-up models added dichotomous variables reflecting African American race and Hispanic ethnicity to these models to determine whether race/ethnicity was related to cognitive performance independent of structural MRI and demographic characteristics. Finally, the role of cardiovascular health, a presumed early component of the causal pathway leading to cerebrovascular disease, was examined. Specifically, a covariate reflecting the sum of self-reported cardiovascular conditions, including diabetes, hypertension and heart disease, was added to the models. This variable ranged from 0 to 3, with higher values indicating worse cardiovascular health, and was normally distributed. Collinearity diagnostics were examined to ensure the absence of potential multicollinearity issues in all regression models. All variance inflation factor (VIF) values were below 1.3.

Multiple-group regression analysis was used to compare the strengths of regression paths across racial/ethnic groups. Even when constructs are not estimated as latent factors (i.e., indicated by multiple, observed variables), the latent variable approach to interactions can provide more defensible interpretations of interaction effects.[31] Using this approach, regression models were estimated simultaneously in two groups (i.e., non-Hispanic White and African American or non-Hispanic White and Hispanic). In initial models, regression paths were forced to equivalence across groups. That is, the magnitude and direction of associations between the predictors and the cognitive outcomes were assumed to be the same across race/ethnicity. Subsequent models systematically freed one regression path at a time. That is, the association between a MRI variable and the cognitive outcome was allowed to differ across race/ethnicity. A significant change in the model χ2 was interpreted as evidence for a racial or ethnic difference in the strength of a regression path. These models were then repeated, adding the cardiovascular health covariate described above.

Results

Racial and Ethnic Group Differences in Study Variables

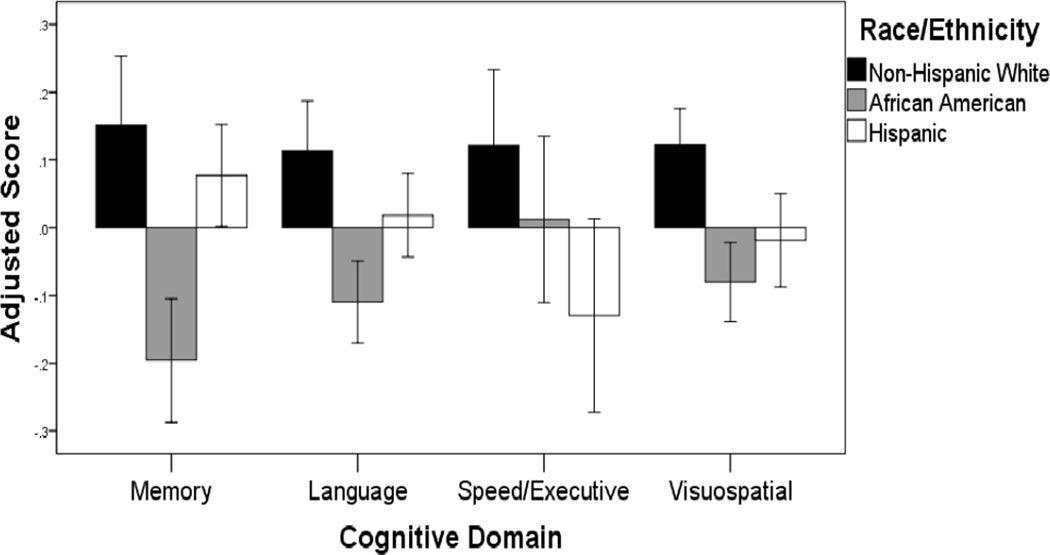

As shown in Table 1, racial/ethnic groups differed in educational attainment, proportion of women, cardiovascular health, WMH volume, hippocampal volume, cortical thickness and all four cognitive composites, but not in age or in the number of individuals with at least one radiologically imaged infarct. Figure 1 displays demographic-adjusted cognitive scores for the three groups, indicating that group differences described in Table 1 are appreciable even after adjustment for age, sex, and education.

Figure 1.

Cognitive scores, adjusted for age, sex and education are shown separately for the three racial/ethnic groups. Scores correspond to residualized z-score composites. Error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals.

Predictors of Cognition in the Whole Sample

Results from four separate regression models examining predictors of performance on the four cognitive composites are summarized in Table 2. Larger WMH volume and smaller values on the cortical thickness composite were each independently associated with poorer performance in all four cognitive domains. Having at least one infarct was independently associated with lower memory, language, and visuospatial scores. Finally, smaller hippocampal volume was independently associated with lower scores on memory and speed/executive functioning. With regard to standardized estimates, hippocampal volume was the strongest MRI predictor of memory (β=0.14), infarct was the strongest MRI predictor of language (β=−0.12) and visuospatial performance (β=−0.13), and WMH volume was the strongest MRI predictor of speed/executive functioning (β=−0.11). Younger age and greater educational attainment were each independently associated with higher cognitive test scores in all four domains, while female sex was only associated with higher memory scores.

Table 2.

Predictors of cognition in the whole sample (standardized)

| Model 1: Memory |

Model 2: Language |

Model 3: Speed/ Executive functioning |

Model 4: Visuospatial |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.18 (0.04)** | −0.15 (0.03)** | −0.16 (0.04)** | −0.14 (0.03)** |

| Education | 0.26 (0.04)** | 0.61 (0.03)** | 0.43 (0.03)** | 0.57 (0.03)** |

| Female | 0.12 (0.04)* | 0.01 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.04 (0.03) |

| WMH volume | −0.09 (0.04)* | −0.07 (0.03)* | −0.11 (0.04)* | −0.08 (0.03)* |

| Infarct | −0.08 (0.04)* | −0.12 (0.03)** | −0.06 (0.04) | −0.13 (0.03)** |

| Hippocampal volume | 0.14 (0.04)* | −0.02 (0.03) | 0.08 (0.04)* | −0.01 (0.04) |

| Cortical thickness | 0.09 (0.04)* | 0.12 (0.03)** | 0.08 (0.04)* | 0.09 (0.03)* |

p<.001

p<.05

Next, dichotomous variables representing African American race and Hispanic ethnicity were added to the models described above. Independent of the MRI predictors and demographic covariates, African American race was associated with lower scores on memory, language and visuospatial composites (all p’s<.001), while Hispanic ethnicity was associated with lower composite scores on speed/executive functioning and visuospatial skill (all p’s<.001). Results were unchanged following addition of the cardiovascular health covariate to all models.

Racial and Ethnic Group Differences in MRI Predictors of Cognitive Domains

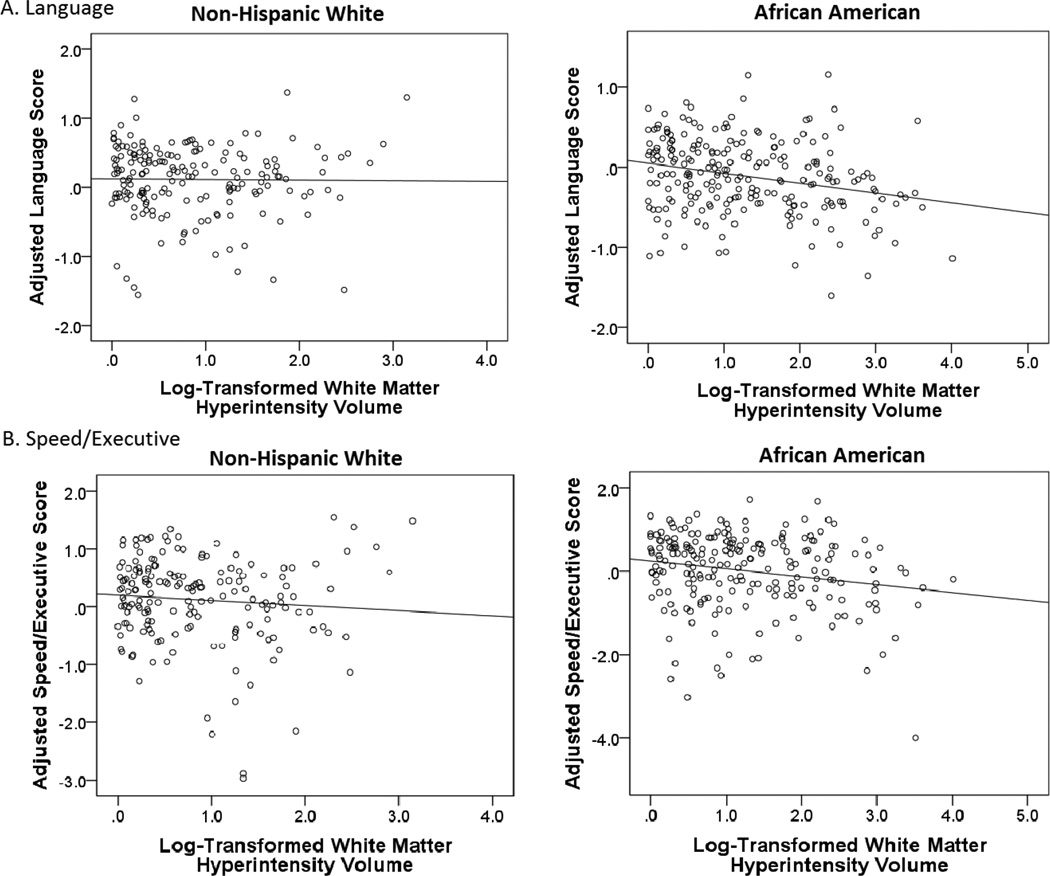

Larger WMH volume was associated with worse performance on language (B=−0.01; SE=0.00; β= −0.16; p=.003) and speed/executive functioning composites (B=−0.02; SE=0.01; β= −0.17; p=.006) among African Americans, but not non-Hispanic Whites (language: B=0.02; SE=0.01; β=0.09; p=.135; speed/executive functioning: B=0.02; SE=0.02; β=0.06; p=.364). This difference was evidenced by significantly improved model fit when regression paths between WMH volume and language, and between WMH volume and speed/executive functioning, were allowed to differ across non-Hispanic Whites and African Americans (see Table 3). This pattern of results was not substantially changed upon addition of the cardiovascular health covariate. While the difference in the magnitude of the association between WMH volume and speed/executive functioning was at trend (Δχ2(1)= −3.63; p=.06), WMH volume remained significantly associated with speed/executive functioning among African Americans (B=−0.02; SE=0.01; β= −0.17; p=.006), but not non-Hispanic Whites (B=0.01; SE=0.02; β=0.06; p=.42), independent of cardiovascular health. Figure 2 displays simple associations between WMH volume and demographic-adjusted cognitive scores for language and speed/executive functioning domains, stratified by racial group (i.e., non-Hispanic White, African American). No racial group differences in the regression paths between any of the MRI predictors and cognition were identified for memory or visuospatial composites.

Table 3.

Changes in chi square with freeing of individual regression paths in multiple-group models

| Memory | Language | Speed/Executive functioning |

Visuospatial | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African American versus non-Hispanic White | ||||

| WMH volume | −0.03 | −5.73* | −4.09* | −1.35 |

| Infarct | −0.14 | −0.65 | −0.07 | −0.02 |

| Hippocampal volume | −1.0 | −0.01 | −0.00 | −0.34 |

| Cortical thickness | −1.5 | −2.05 | −1.21 | −0.67 |

| Hispanic versus non-Hispanic White | ||||

| WMH volume | −0.47 | −0.94 | −3.76 | −2.42 |

| Infarct | −0.03 | −0.87 | −1.11 | −0.01 |

| Hippocampal volume | −4.41* | −1.33 | −2.81 | −0.25 |

| Cortical thickness | −0.06 | −0.52 | −0.17 | −0.04 |

p<.05

Figure 2.

Simple associations between WMH volumes and demographic-adjusted cognitive scores stratified by racial group for (A) language and (B) speed/executive. Cognitive scores correspond to residualized z-score composites.

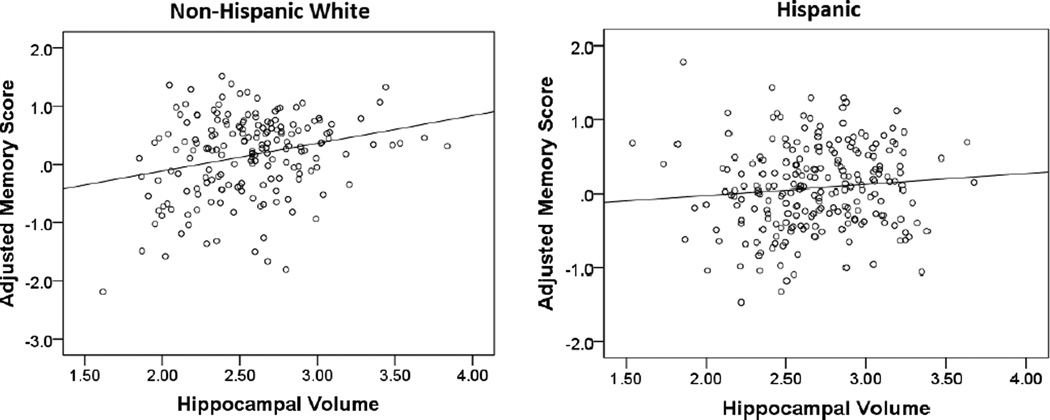

Larger hippocampal volume was associated with higher memory scores among non-Hispanic Whites (B=0.55; SE=0.14; β=0.28; p<.001), but not Hispanics (B=−0.20; SE=0.11; β=−0.12; p=.061). This difference was evidenced by significantly improved model fit when the regression path between hippocampal volume and memory was allowed to differ across non-Hispanic Whites and Hispanics (see Table 3). This pattern of results was not substantially changed upon addition of the cardiovascular health covariate. Figure 2 displays simple associations between hippocampal volume and demographic-adjusted memory, stratified by ethnic group (i.e., non-Hispanic White, Hispanic). No racial/ethnic group differences in the regression paths between any of the MRI predictors and cognition were identified for language, speed/executive functioning, or visuospatial composites.

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that MRI predictors of cognition differed across racial/ethnic groups. Specifically, WMH volume was a stronger predictor of language and speed/executive functioning among African Americans, and hippocampal volume was a weaker predictor of memory among Hispanics, compared with non-Hispanic Whites. These results were identified in the context of numerous differences in level of cognitive, imaging, demographic, and cardiovascular health variables across racial/ethnic groups. Specifically, African Americans and Hispanics attained less education, comprised a larger proportion of women, reported worse cardiovascular health, and had greater WMH burden than non-Hispanic Whites. Additionally, African Americans showed greater atrophy in the set of cortical regions shown to be most sensitive to AD neurodegeneration, compared with non-Hispanic Whites. Non-Hispanic Whites obtained higher scores across cognitive domains of memory, language, speed/executive functioning and visuospatial functioning than African Americans and Hispanics.

Results from the whole-group regression analysis are consistent with the extant literature on MRI predictors of older adults’ abilities in different cognitive domains. Specifically, hippocampal volume was the strongest MRI predictor of memory, WMH volume was the strongest MRI predictor of speed/executive functioning, and infarct was the strongest MRI predictor of language and visuospatial performance. Previous animal and human studies have shown the hippocampus to be a critical structure for memory performance.[32,15] Similarly, volumetric and diffusion tensor imaging studies have repeatedly shown that white matter integrity is crucial in the execution of a variety of speed/executive functioning tasks.[33–35,12] Finally, language and visuospatial deficits are common cognitive symptoms following late-life stroke.[36] Non-significant relationships between certain MRI variables and cognitive domains likely reflect specificity in the neurobiological substrates of cognition.

Results from the multiple group analyses showed relationships between MRI variables and cognition that varied in strength across racial/ethnic groups. First, while hippocampal volume predicted cognitive test scores similarly among African Americans and Whites, smaller hippocampal volume was significantly associated with worse memory test scores among non-Hispanic Whites, but this relationship was at trend among Hispanics. A previous study of MRI predictors of clinical diagnosis (i.e., normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment or dementia) reported a similar interaction between Hispanic ethnicity and hippocampal volume such that reduced hippocampal volume was associated with mild cognitive impairment among non-Hispanic Whites, but not among Hispanics.[37] It is possible that other, unmeasured neurobiological and/or psychosocial factors influence memory test performance in Hispanic older adults more than hippocampal atrophy. For example, nearly all of the Hispanics in this study experienced a unique developmental environment outside of the U.S. that could have led to structural or functional differences in memory networks. Unique psychosocial factors such as immigration experiences and test anxiety may also play a bigger role in memory performance for Hispanics than non-Hispanic Whites in this study.

Second, larger WMH volume was associated with lower performance on tasks of language and speed/executive scores among African Americans, but not among non-Hispanic Whites. A previous study of cognitive functioning among African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites in the Chicago Health and Aging Project did not find significant interactions between race and WMH volume.[38] However, there were no racial differences in WMH volume in that study, which contrasts the findings of this and many other studies of older adults.[39–41] In addition, cognitive measures in that study did not include tests of executive functioning as they did in the current study, which included verbal abstraction and task-switching. A previous study of cognitive functioning among African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study did not find significant interactions between race and WMH volume.[42] However, this study included younger participants (age 55 and up), did not include tests of executive functioning, and quantified WMH as a 10-category, rater-defined variable as opposed to whole-brain WMH volume.

If replicated, these findings of group-specific associations between WMH and cognition may reflect threshold or synergistic effects. That is, a relatively high level of WMH may need to be present in the brain in order to affect cognition, and since African Americans have higher levels of WMH, the relationship between white matter disease burden and cognitive function is more readily seen among this racial group. It is also possible that WMH have a greater impact on cognitive functioning in the presence of certain psychological or environmental variables (e.g., educational quality) or other types of neuropathology (e.g., AD pathology). Indeed, African Americans were found to have more hippocampal atrophy and cortical thinning in “AD signature” regions, compared with non-Hispanic Whites in this study.

Limitations of this study include its cross-sectional design, which prohibits causal interpretations, and its dichotomous measure of infarcts, which may have limited power to detect associations between infarcts and cognitive test performance. Strengths of this study include its large, well-characterized cohort of roughly equal numbers of three racial/ethnic groups, the comprehensive neuropsychological battery used to derive cognitive composite scores, consideration of cardiovascular health, and inclusion of multiple MRI measures simultaneously to characterize unique brain-behavior relationships. The unique community-based recruitment strategy in WHICAP minimizes many of the confounds present in other studies, even when they include sufficient numbers of ethnic minorities. Specifically, a neighborhood-based recruitment strategy was used to recruit members of all racial/ethnic groups in WHICAP, taking advantage of the positive and consistent interaction of Columbia University Medical Center with residents of Northern Manhattan. Other studies often employ different recruitment strategies in order to increase participation of ethnic minorities. In addition, all WHICAP participants are residents of a geographic region of approximately 10 square miles. In multi-site studies, racial/ethnic group differences are often confounded by geographic differences. However, it should be noted that due to longstanding differences in the socioeconomic and sociocultural experience of racial/ethnic minorities and immigrant groups, it is unlikely that diverse cohorts will ever be perfectly matched on all experiential variables.

Conclusion

In this study, MRI predictors of memory, language, and speed/executive functioning appear to differ across non-demented African American, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic White older adults. These results highlight the need for more diverse samples in the study of cognitive aging and AD, as the type and relation of the neurobiological substrates of cognitive impairment may be different for individuals of different backgrounds.

Figure 3.

Simple associations between hippocampal volumes and demographic-adjusted memory scores stratified by ethnic group. Memory scores correspond to residualized z-score composites.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (grant numbers AG037212, AG034189, AG047963). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Aisen PS, Weiner MW, et al. Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:119–128. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70299-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ADNI Demographic Report. 2012 Retrieved from http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/ADNI_Enroll_Demographics.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Census. Race. 2013 Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/topics/population/race.html.

- 4.U.S. Census. Hispanic Origin. 2013 Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/population/hispanic/

- 5.U.S. Census. Educational attainment. 2013 Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/hhes/socdemo/education/

- 6.Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2012. Jun, Older Americans 2012: Key Indicators of Well-Being. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang MX, Cross P, Andrews H, Jacobs DM, Small S, Bell K, Mayeux R. Incidence of AD in African-Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and Caucasians in northern Manhattan. Neurology. 2001;56:49–56. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurland BJ, Wilder DE, Lantigua R, et al. Rates of dementia in three ethnoracial groups. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14:481–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang MX, Cross P, Andrews H, Jacobs DM, Small S, Bell K, Mayeux R. Incidence of AD in African-Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and Caucasians in northern Manhattan. Neurology. 2001;56:49–56. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sahota A, Yang M, Gao S, Hui SL, Baiyewu O, et al. Apolipoprotein E-associated risk for Alzheimer’s disease in the African-American population is genotype dependent. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:659–661. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta Analysis Consortium. JAMA. 1997;278:1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kloppenborg RP, Nederkoorn PJ, Geerlings MI, van den Berg E. Presence and progression of white matter hyperintensities and cognition: a meta-analysis. Neurology. 2014;82:2127–38. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Rooij FG, Schaapsmeerders P, Maaijwee NA, van Duijnhoven DA, de Leeuw FE, et al. Persistent cognitive impairment after transient ischemic attack. Stoke. 2014;45:2270–2274. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pendlebury ST, Markwick A, de Jager CA, Zamboni G, Wilcock GK, Rothwell PM. Difference in cognitive profile between TIA, stroke and elderly memory research subjects: a comparison of the MMSE and MoCA. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;34:48–54. doi: 10.1159/000338905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mielke MM, Okonkwo OC, Oishi K, Mori S, Tighe S, et al. Fornix integrity and hippocampal volume predict memory decline and progression to Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickerson BC, Bakkour A, Salat DH, Feczko E, Pacheco J, et al. The cortical signature of Alzheimer’s disease: regionally specific cortical thinning relates to symptom severity in very mild to mild AD dementia and is detectable in asymptomatic amyloid-positive individuals. Cerb Cortex. 2009;19:497–510. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang H, Sachdev PS, Wen W, Kochan NA, Zhu W, et al. Neuroanatomical correlates of cognitive performance in late life. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2011;32:216–226. doi: 10.1159/000333372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carmichael O, Mungas D, Beckett L, Harvey D, Tomaszewski Farias S, et al. MRI predictors of cognitive change in a diverse and carefully characterized elderly population. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manly JJ, Bell-McGinty S, Tang MX, Schupf N, Stern Y, Mayeux R. Implementing diagnostic criteria and estimating frequency of mild cognitive impairment in an urban community. Archives of Neurology. 2005;62:1739–1746. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.11.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brickman AM, Schupf N, Manly JJ, Luchsinger JA, Andrews H, Tang MX, Brown TR. Brain morphology in older African Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and whites from northern Manhattan. Archives of Neurology. 2008;65:1053–1061. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.8.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brickman AM, Muraskin J, Zimmerman ME. Structural neuroimaging in Alzheimer's disease: do white matter hyperintensities matter? Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2009;11(2):181–190. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.2/ambrickman. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brickman AM, Sneed JR, Provenzano FA, Garcon E, Johnert L, Muraskin J, Roose SP. Quantitative approaches for assessment of white matter hyperintensities in elderly populations. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2011;193(2):101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brickman AM, Provenzano FA, Muraskin J, Manly JJ, Blum S, Apa Z, Mayeux R. Regional white matter hyperintensity volume, not hippocampal atrophy, predicts incident Alzheimer disease in the community. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(12):1621–1627. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reitz C, Schupf N, Luchsinger JA, Brickman AM, Manly JJ, et al. Validity of self-reported stroke in elderly African Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and Whites. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:834–840. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeCarli C, Massaro J, Harvey D, Hald J, Tullberg M, et al. Measures of brain morphology and infarction in the Framingham Heart Study: establishing what is normal. Neurobio Aging. 2005;26:491–510. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siedlecki KL, Manly JJ, Brickman AM, Schupf N, Tang MX, Stern Y. Do neuropsychological tests have the same meaning in Spanish speakers as they do in English speakers? Neuropsychology. 2010;24:402–411. doi: 10.1037/a0017515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buschke H, Fuld PA. Evaluating storage, retention, and retrieval in disordered memory and learning. Neurology. 1974;24:1019–1025. doi: 10.1212/wnl.24.11.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benton AL. The Visual Retention Test. New York: The Psychological Corporation; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosen W. The Rosen Drawing Test. Bronx, NY: Veterans Administration Medical Center; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Revised Third. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marsh HW, Wen Z, Nagengast B, Hau K-T. Structural equation models of latent interaction. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 436–458. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Squire LR. Memory and the hippocampus: a synthesis from findings with rats, monkeys, and humans. Psychol Rev. 1992;99:195–231. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.99.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papp KV, Kaplan RF, Springate B, Moscufo N, Wakefield DB, et al. Processing speed in normal aging: effects of white matter hyperintensities and hippocampal volume loss. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2014;21:197–213. doi: 10.1080/13825585.2013.795513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Birdsill AC, Koscik RL, Jonaitis EM, Johnson SC, Okonkwo OC, et al. Regional white matter hyperintensities: aging, Alzheimer’s disease risk, and cognitive function. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:769–776. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.10.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hedden T, Mormino EC, Amariglio RE, Younger AP, Schultz AP, et al. Cognitive profile of amyloid burden and white matter hyperintensities in cognitively normal older adults. J Neurosci. 2012;32:16233–16242. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2462-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edwards JD, Jacova C, Sepehry AA, Pratt B, Benavente OR. A quantitative systematic review of domain-specific cognitive impairment in lacunar stroke. Neurology. 2013;80:315–322. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827deb85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeCarli C, Reed BR, Jagust W, Martinez O, Ortega M, Mungas D. Brain behavior relationships among African Americans, Whites, and Hispanics. Alz Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22:382–391. doi: 10.1097/wad.0b013e318185e7fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aggarwal NT, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, De Jager PL, Bennett DA, Evans DA, et al. The association of Magnetic Resonance Imaging measures with cognitive function in a biracial population sample. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:475–482. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bryan CS. Race and health care. J S C Med Assoc. 2008;95:116–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nyquist PA, Bilgel MS, Gottesman R, Yanek LR, Moy TF, et al. Extreme deep white matter hyperintensity volumes are associated with African American race. Cerbrovasc Dis. 2014;37:244–250. doi: 10.1159/000358117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liao D, Cooper L, Cai J, et al. The prevalence and severity of white matter lesions, their relationship with age, ethnicity, gender, and cardiovascular disease risk factors: the ARIC Study. Neuroepidemiology. 1997;16:149–162. doi: 10.1159/000368814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mosley TH, Knopman DS, Catellier DJ, Bryan N, Hutchinson RG, et al. Cerebral MRI findings and cognitive functioning: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Neurology. 2005;64:2056–2062. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000165985.97397.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]