Abstract

Introduction:

The aim of this in vitro study is to evaluate the role of light and laser sources in the bleaching ability of 37.5% H2 O2 on extracted human teeth.

Materials and Methods:

About 30 caries-free single-rooted maxillary central incisors were used for the study. Specimens were prepared by sectioning the crown portion of teeth mesiodistally, and labial surface was used for the study. Specimens were then immersed in coffee solution for staining. Color of each tooth was analyzed using Shadestar, a digital shademeter. Specimens were then divided into three groups of 10 each and were subjected to bleaching with 37.5% H2 O2, 37.5% H2 O2 + light activation, and 37.5% H2 O2 + laser activation, respectively. Postbleaching, the color was analyzed for all the specimens immediately and then after 1, 2, and 3 weeks intervals, respectively.

Results:

All the statistical analyses were done using SPSS version 17. Intra- and inter-group comparisons were done with Friedman test and Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA, respectively. Statistical analysis concluded with a significant improvement in their shade values from baseline in all the three groups. Halogen light activation and laser-activated groups showed comparatively enhanced bleaching results over no-activation group, though the difference was not statistically significant.

Conclusion:

The results of the present study show that bleaching assisted with halogen light and laser showed increased lightness than nonlight activated group. Durability of bleaching results obtained postbleaching was maintained throughout the experimental trail period of 3 weeks for both halogen light and laser activation group, whereas no-light activation group presented with shade rebound after 2 weeks postbleaching.

Keywords: Bleaching, halogen light, hydrogen peroxide, laser, shade star

INTRODUCTION

Tooth color is considered as the most important aspect to assess patient's perception to dental attractiveness. It has been observed that most of the people are dissatisfied with their tooth color, thereby demanding for information regarding the efficacy of various procedures available to enhance tooth color such as micro/macro abrasion, bleaching, veneers, crowns, and composite restoration.

Tooth discoloration can be broadly classified into extrinsic and intrinsic discoloration. Careful diagnosis and treatment planning can lighten teeth in challenging situation, with bleaching considered to be the simplest, less invasive,[1] and economic approach. Harlan, in 1884, published what is believed to be the first report of hydrogen peroxide which he called hydrogen dioxide. Since then, many manufacturing companies are mixing various chemical solutions along with hydrogen peroxide to speed up in-office bleaching. Attempts are even being made to speed up the bleaching process in the office by using an electric current,[2] ultra-violet rays,[3] and other heating instruments and lights.[4]

Hydrogen peroxide being unstable splits into hydroxyl (HO·), perhydroxyl radicals (HO2·) superoxide anions (O2·−), and reactive oxygen molecules (O) that attack the long and strongly colored molecules to achieve stability, thereby generating other radicals. The longer chain molecules then split in shorter chains which reflect light differently than its precursors and thus the tooth appears lighter. Dissociation of hydrogen peroxide to obtain free radicals can be accelerated using chemical, heat, or light to reduce the treatment time.

Tooth color is determined visually using a set of color tabs/shades called shade guides such as vita-classic, Vitapan-3D Master, whereas objective method for measuring shade encourages the use of electronic devices such as spectrophotometer, colorimeter, or RGB system. Shadestar is a digital shade-taking device, which gives reliable and reproducible objective results in multiple shade standards such as Vita-Classic, Vitapan 3D-Master, Ceram-X Mono, and Ceram-X duo.

Therefore, the aim of this in vitro study is to evaluate the role of light and laser sources in the bleaching ability of 37.5% H2 O2 on extracted human teeth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

About 30 extracted human maxillary central incisors were visually examined for the absence of caries, cracks, restorations, or other surface defects. Specimens were then analyzed using an ultrasonic scaler and polished with pumice-water paste. Samples were then prepared by sectioning crown of each specimen which was sectioned at a distance of 7 mm from the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) while the roots were sectioned at a distance of 4 mm from the CEJ followed by mesio-distal sectioning, parallel to the long axis of the tooth. The labial half of each tooth was used for the study and the lingual half was discarded. For staining the samples, samples were immersed in 200 ml of a freshly prepared coffee solution (Nescafe Classic), as reported earlier by Sulieman et al.[5] and stored in a bacteriologic oven for 7 days at a temperature of 37°C.

The specimens were then washed under running tap water and embedded in a customized putty mold, covering its labial surface. A circular, measured preselected area of 7 mm diameter was cut through the putty mold on the labial surface of specimen to suit the measuring tip diameter of Shadestar, to prevent external light interferences, and to standardize color-gauging. The vita classic values registered at this stage with Shadestar were recorded as baseline values. Each specimen was labeled with its relevant shade and stored in normal saline. Specimens were randomly divided into three different experimental groups of 10 specimens each.

Group I

A 2 mm thick layer of 37.5% hydrogen peroxide gel (Pola office+) was applied on the specimens at 3 intervals for 8 min each with a waiting period of 3 min between each bleaching session, as per manufacturer's instructions. The gel was removed with a suction tip, tooth was later washed under running water, and then the shade was measured in the predetermined area.

Group II

A 2 mm thick layer of 37.5% hydrogen peroxide gel was applied and each specimen was photoactivated at 3 intervals for 8 min each with a waiting period of 3 min between each bleaching session, using halogen light (Beyond, Stafford, Tx, USA) with power density of 150 W and high-intensity blue light (480-520 nm), kept at a distance of 15 mm from the tooth surface. Water-saturated gauze pad was placed under each specimen during bleaching procedure to prevent dehydration.

Group III (with laser activation)

A 2 mm thick layer of 37.5% hydrogen peroxide bleaching gel was applied and activated using Picasso diode laser (GaAlAs) with a wavelength of 810 nm and it was preset into pulsed mode #4 of 7 W power with duration of 9.9 s and an interval of 1.5 s. The bleaching hand piece of Picasso diode laser was held to cover 2 teeth at a time, for a period of 30 s. The procedure was repeated 6 times giving a total activation period of 3 min per cycle followed by a holding period of 4 min. The whole procedure was repeated 4 times, with the total laser bleaching time being 28 min as per the manufacturer's instructions. A water-saturated gauze pad was placed under each specimen during bleaching procedure to prevent dehydration.

Vita classic shade guide readings of each specimen were measured and recorded immediately postbleaching, over respective intervals of 1, 2, and 3 weeks of storage in normal saline, using Shadestar. The obtained readings were scored according to value-oriented vita classic shade guide readings as used by Pohjola et al. and Leonard et al. in their studies[6,7] for evaluation of bleaching efficiency.

All the statistical analyses were done using SPSS version 17 (SPSS Inc,III,Chicago, USA). Friedman test was done for intragroup comparison (P < 0.01) and Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA was done for intergroup comparison (P < 0.017).

RESULTS

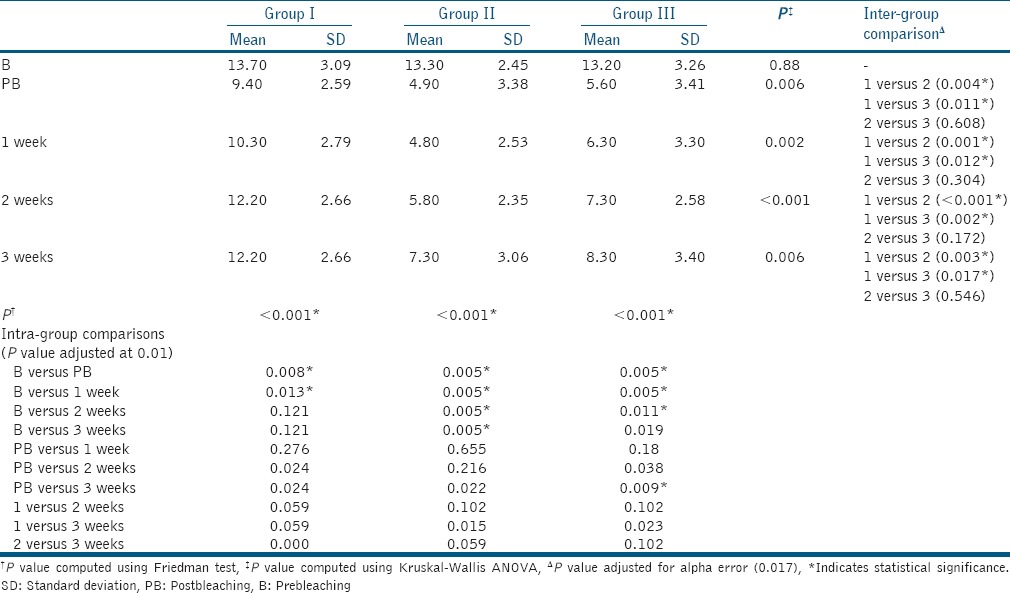

At baseline, no statistically significant difference in the mean shade values is found among the three experimental groups. All the groups produced significant increase in lightness from baseline following bleaching, with the Group II showing comparatively lighter teeth followed by Group III and I. There was statistically significant difference in mean shade values immediately postbleaching and over a period of 1, 2, and 3 weeks postbleaching between Group I and II and between Group I and III. However, no statistically significant difference in the degree of lightness was observed between Groups II and III as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Intra- and inter-group mean shade values comparison

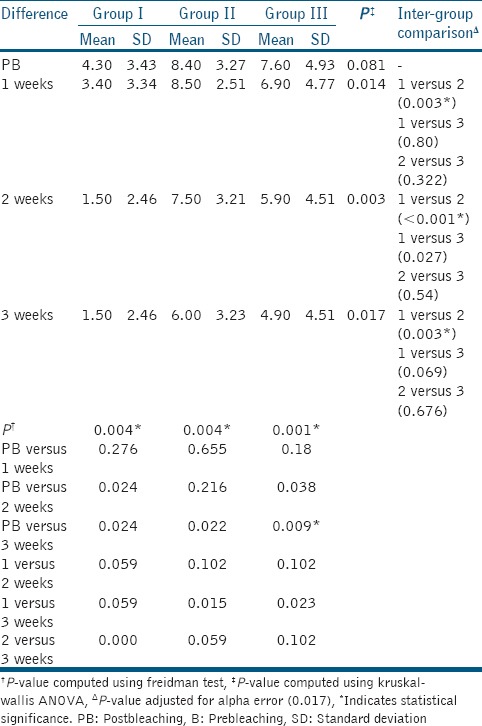

The mean shade change values from baseline immediately postbleaching was found to be highest for Group II, followed by Group III and I. The difference in mean shade change values from baseline was found to be significant between Group I and II at duration of 1, 2, and 3 weeks postbleaching. However, no statistically significant difference was observed between Group I and III; Group II and III as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Intra- and Inter-group mean shade change value comparison

Statistically significant increase in lightness from baseline shade values was observed immediately postbleaching in all the three groups. In Groups II and III, this increase in lightness was maintained throughout the experimental period. Group I showed an increase in value-oriented scores, with no statistically significant difference from their baseline values at 2 weeks postbleaching.

DISCUSSION

Tooth whitening, also referred to as bleaching, is considered to be the most conservative method to manage a discolored tooth when compared to all the above-mentioned treatment modalities.[8,9]

Diffusion of peroxide into the organic matter of tooth structure depends on the diffusion coefficient, duration of application, and concentration of active bleaching agent.[10] Hence, in the present study, 37.5% hydrogen peroxide is used as a bleaching agent. Photocatalytic interactions accelerate the dissociation of hydrogen peroxide by heating up the bleaching agent, thereby increasing the interaction between reactive oxygen and pigmented molecules, leading to enhanced bleaching efficiency.[11]

In the present study, Shadestar, a digital shade measuring device, is used to evaluate the shade during the trial as it gives quick and reliable readings. Considering the reliability and accuracy of vita classic shade guide,[12] in the present study, value-oriented vita classic shade guide scale[6,7] was used to calculate shade change from baseline.

Laser being monochromatic, coherent, and collimated is a differentiated source of energy,[13] when irradiated on a bleaching agent, the chromophores present in the gel absorb the light and thus activate the molecule, thereby improving tooth whitening ability. Few studies showed enhanced bleaching results on using laser,[14] while other studies showed no significant improvement.[15,16] In the present study, laser activation produced comparatively enhanced bleaching efficacy with hydrogen peroxide gel when compared to nonactivation group, which is in correlation with the results obtained by Calatayud et al.[17]

Halogen light, one of the most common light sources used in power bleaching, transmits higher temperatures without causing discomfort to the patients.[18] Results of the present study demonstrated greater average shade change values following bleaching for halogen-activated group than nonactivation and laser activation groups. This might be because of difference in the power density of both the activation sources, leading to variation in the degree of heat produced in the bleaching gel which in turn enhances the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide. The results obtained were in accordance with the study conducted by Patel et al.[19] where halogen light provided comparatively enhanced tooth whitening than diode laser and plasma arc light.

Durability of bleaching results was found to be maintained throughout the trial period of 3 weeks for halogen-activated group. However, for laser-activated group, the effect of bleaching therapy diminished over a period of 2 weeks and for no-light bleaching group, the effect lasted no longer than a week after bleaching. Though the exact mechanism of samples retaining the shade is not clearly understood, it was observed earlier that depending on the degree of porosity in the enamel and dentin, oxygen gets entrapped in the tooth structure and facilitates further bleaching. Heating of bleaching gel further increases the penetration of peroxide into the organic matter of tooth structure, and continuous oxidation takes place over time.

However, this is an in vitro study, whereas in clinical situations, teeth are constantly exposed to various staining substances causing variations in the response to bleaching, this could be a limitation. Furthermore, future studies can be done with larger sample size and different activation modes for bleaching.

CONCLUSION

On the basis of results obtained from the present study, following conclusions can be drawn:

All the groups produced significant increase in lightness from baseline following bleaching. Halogen and laser light activation group showed increased lightness than nonlight-activated group with no statistically significant difference

Halogen and laser light activation group maintained the shade obtained for 3 weeks postbleaching; whereas no-light activation group presented with shade rebound after 2 weeks postbleaching.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Abouassi T, Wolkewitz M, Hahn P. Effect of carbamide peroxide and hydrogen peroxide on enamel surface: An in vitro study. Clin Oral Investig. 2011;15:673–80. doi: 10.1007/s00784-010-0439-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Westlake A. Bleaching teeth by electricity. Am J Dent Sci. 1895;29:101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenthal P. The combined use of ultra-violet rays and hydrogen dioxide for bleaching teeth. Dent Cosm. 1911;53:246–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbot CH. Bleaching discolored teeth by means of 30% perhydrol and electric light rays. J Allied Dent Soc. 1918;13:259. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sulieman M, Addy M, Macdonald E, Rees JS. The bleaching depth of a 35% hydrogen peroxide based in-office product: A study in vitro. J Dent. 2005;33:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leonard RH, Jr, Bentley C, Eagle JC, Garland GE, Knight MC, Phillips C. Nightguard vital bleaching: A long-term study on efficacy, shade retention. Side effects, and patients’ perceptions. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2001;13:357–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2001.tb01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pohjola RM, Browning WD, Hackman ST, Myers ML, Downey MC. Sensitivity and tooth whitening agents. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2002;14:85–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2002.tb00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papathanasiou A, Bardwell D, Kugel G. Combining in office and take home whitening systems. Contemp Esthet Res Pract. 2000;4:88–91. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thosre D, Mulay S. Smile enhancement the conservative way: Tooth whitening procedures. J Conserv Dent. 2009;12:164–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.58342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawamoto K, Tsujimoto Y. Effects of the hydroxyl radical and hydrogen peroxide on tooth bleaching. J Endod. 2004;30:45–50. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200401000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Moor RJ, Verheyen J, Diachuk A, Verheyen P, Meire MA, De Coster PJ, et al. Insight in the chemistry of laser-activated dental bleaching. Scientific World Journal 2015. 2015:650492. doi: 10.1155/2015/650492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim-Pusateri S, Brewer JD, Dunford RG, Wee AG. In vitro model to evaluate reliability and accuracy of a dental shade-matching instrument. J Prosthet Dent. 2007;98:353–8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(07)60119-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pick RM. Using lasers in clinical dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 1993;124:37–4. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1993.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lizarelli RF, Moriyama LY, Bagnato VS. A nonvital tooth bleaching technique with laser and LED. J Oral Laser Appl. 2002;2:45–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baroudi K, Hassan NA. The effect of light-activation sources on tooth bleaching. Niger Med J. 2014;55:363–8. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.140316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wetter NU, Walverde D, Kato IT, Eduardo Cde P. Bleaching efficacy of whitening agents activated by xenon lamp and 960-nm diode radiation. Photomed Laser Surg. 2004;22:489–93. doi: 10.1089/pho.2004.22.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calatayud JO, Calatayud CO, Zaccagnini AO, Box MJ. Clinical efficacy of a bleaching system based on hydrogen peroxide with or without light activation. Eur J Esthet Dent. 2010;5:216–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldstein RE, Garber DA. Complete Dental Bleaching. 3rd ed. Chicago: Quintessence; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel A, Louca C, Millar BJ. An in vitro comparison of tooth whitening techniques on natural tooth colour. Br Dent J. 2008;204:E15. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]