Abstract

Biomimetic materials that display natural bioactive signals derived from extracellular matrix molecules like laminin and fibronectin hold promise for promoting regeneration of the nervous system. In this work, we investigated a biomimetic peptide amphiphile (PA) presenting a peptide derived from the extracellular glycoprotein tenascin-C, known to promote neurite outgrowth through interaction with β1 integrin. The tenascin-C mimetic PA (TN-C PA) was found to self-assemble into supramolecular nanofibers and was incorporated through co-assembly into PA gels formed by highly aligned nanofibers. TN-C PA content in these gels increased the length and number of neurites produced from neurons differentiated from encapsulated P19 cells. Furthermore, gels containing TN-C PA were found to increase migration of cells out of neurospheres cultured on gel coatings. These bioactive gels could serve as artificial matrix therapies in regions of neuronal loss to guide neural stem cells and promote through biochemical cues neurite extension after differentiation. One example of an important target would be their use as biomaterial therapies in spinal cord injury.

Keywords: Self assembly, Tenascin-C mimetic peptide, Peptide amphiphile, Neurite growth, Cell migration

1. Introduction

Bioactive materials hold promise for promoting regeneration of the nervous system by providing both physical and biochemical cues to cells in the damaged tissue [1–4]. Biomimetic biomaterials can incorporate native cues provided by extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins [5], such as laminin and fibronectin, which can promote cellular migration and guide neurite outgrowth during neural development and regeneration. One successful approach to mimicking ECM protein functionality has been covalent ligation of a peptide ligand from a native protein to a material to impart biological activity, a common example being the use of the peptide RGD found in fibronectin and other proteins, to enable cell adhesion through interaction with integrins [6]. In this work, we describe the development of a biomimetic material incorporating a peptide derived from the ECM glycoprotein tenascin-C to aid in neural tissue repair.

The glycoprotein tenascin-C plays a role in regeneration of the spinal cord [7,8]. It is heavily expressed following spinal cord injury and regions of high expression show axon ingrowth [8]. Inhibition of tenascin-C expression after spinal cord injury leads to a reduction in supraspinal axon regrowth and synapse formation with spinal motor neurons and impairs locomotor recovery [7]. Tenascin-C also plays a role in guidance of neural progenitors during brain development [9]. This protein is highly expressed in the subventricular zone (SVZ), contributing to the stem cell niche by changing the response to growth factors, enhancing sensitivity to FGF2 and decreasing sensitivity to BMP4, which promotes EGF receptor acquisition [10]. Tenascin-C is also heavily expressed in the extracellular space of the rostral migratory stream [9], a pathway that migratory neuroblasts from the SVZ follow to the olfactory bulb, where they become new interneurons. Tenascin-C acts through integrin-dependent mechanisms enabling cell adhesion. Meiners and colleagues have discovered a linear peptide within tenascin-C, VFDNFVLK, that increases neurite length [11] through interactions with α7β1-integrin [12]. This peptide was previously linked covalently to electrospun polyamide fibers, which were coated onto coverslips [13]. Several primary neurons (cerebellar granule neurons, spinal motor neurons, and dorsal root ganglion neurons), when cultured in vitro on the polyamide fiber coatings presenting the tenascin-C peptide, showed increased average neurite lengths [13]. Materials presenting this peptide have been shown to effect non-neuronal systems as well. In a recent report, coatings of self-assembled nanofibers presenting this peptide were shown to promote osteogenic differentiation from rat mesenchymal stem cells [14].

In this work our goal has been to incorporate the tenascin-C derived peptide mentioned above into self-assembling nanofibers formed by peptide amphiphiles (PAs) [4,15,16] capable of forming aligned nanofiber gels that can encapsulate and support cells. PAs developed in our laboratory can be designed to self-assemble into high aspect ratio nanofibers and that gels when exposed to physiological salt solutions containing divalent cations, such as Ca2+ [17]. Incorporation of the peptapeptide IKVAV from the ECM molecule laminin has been used to promote differentiation of neural progenitors into neurons in vitro [18], to reduce gliosis after spinal cord injury in vivo [19], and to promote neurite growth in vitro from cell encapsulated in gels [18,20,21] and in vivo in the spinal cord [19,21]. Thermally treated nanofibers can be aligned in a single direction during gelation by application of shear stress, for example, by pipetting through a CaCl2-containing gelling solution [22]. These aligned gels can encapsulate cells, promote aligned neurite growth and guide cell migration in the direction of the nanofibers [21]. In this work we have investigated PAs containing the bioactive peptide sequence derived from tenascin-C in aligned PA nanofiber gels encapsulating neurons and analyzed neurite outgrowth. We also investigated neurosphere-derived cell (NDC) migration on these aligned nanofiber gels.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Peptide synthesis and purification

PAs were synthesized using standard solid phase peptide synthesis methods with Fmoc-protected amino acids and Rink-resin purchased from Novabiochem Corporation, as previously described [20]. Briefly, for each coupling, the Fmoc protecting group was removed by shaking the resin in 30% piperidine in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF). Amino acids were coupled by adding the Fmoc- protected amino acids with O-benzotriazole-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) and Diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) in DMF. The palmitoyl tail was added using a molar ratio of palmitic acid/HBTU/DIEA of 4:4:6. PAs were cleaved with 95% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), 2.5% triisopropyl silane (TIS) and 2.5% H2O. PAs were purified by preparatory scale reverse phase HPLC running a mobile phase gradient of 100% H2O to 100% acetonitrile with 0.1% ammonium hydroxide. HPLC fractions were checked for the correct compound using electrospray ionization mass spectroscopy (ESI-MS), rotary evaporated to remove acetonitrile, and lyophilized (Labconco, FreezeZone6).

2.2. Conventional transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Samples for conventional TEM microscopy were prepared from 0.1 wt% PA solution dissolved in milli-Q water or saline and adjusted to a pH of 7.2–7.4 by adding NaOH. The solutions were then heated to 80 °C in a water bath for 1 h, and then slowly cooled to room temperature. 2 μL of a 0.1 wt% PA solution was pipetted onto a carbon formvar grid (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and allowed to dry. The samples were then negatively stained with 2 wt% uranyl acetate solution. Each sample was imaged using a JEOL 1230 TEM operating at 100 kV.

2.3. Small-angle X-ray ccattering (SAXS) and data modeling

Samples for SAXS were prepared by dissolving 1 wt% PA solutions in a 150 mM NaCl and 3 mM KCl solution, adjusted to a pH of 7.2–7.4 by adding NaOH. SAXS measurements were obtained using beamline 5ID-D, in the DuPont-Northwestern-Dow Collaborative Access team (DND-CAT) Synchrotron Research Center at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory. A double-crystal monochromator was used to select X-rays with energy of 15 keV, or a wavelength λ = 0.83 Å. The data was collected with a CCD detector positioned 245 cm behind the sample. The scattering intensity was recorded in interval 0.0005 < q < 0.23 Å−1. The wave vector defined as q = (4π/λ) sin (θ/2), where θ is the scattering angle. The 2D SAXS patterns were azimuthally averaged and the background was subtracted using standard methods to produce intensity vs. q profiles using the two-dimensional data reduction program FIT2D. Data analysis was based on fitting the scattering curve to an appropriate model by a least-squares method using software provided by NIST (NIST SANS analysis version 7.0 on IGOR). The TN-C PA SAXS curve was fit to a core-shell cylinder model.

2.4. Neurite outgrowth, alignment, and cell viability assays

P19 embryonal carcinoma cells were cultured as described in MacPherson et al. [23]. Media was composed of α-MEM (Gibco), 7.5% newborn calf serum (Lonza), 2.5% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), penicillin (100 units/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (Invitrogen). Neuronal differentiation was induced by treating P19 cells in non-tissue culture-treated Petri dishes with media containing 5 μM retinoic acid (Sigma) for four days. Neurospheres were collected from the Petri dish and allowed to settle in a centrifuge tube for 10 min. Media was removed, then trypsin/EDTA solution was added and the tube was gently agitated for five minutes. Cells were dissociated by triturating the neurospheres, and then media was added to inactivate the trypsin. Cells were centrifuged and the pellet was resuspended in media to a concentration of 25,000 cells/μl. Cells were mixed (1:4) with PA solution. 4 μl of PA/cell solution was pipetted through gelling solution (150 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 25 mM CaCl2) in a line approximately 20 mm long. The gelling solution was removed and media was added to the dish. For experiments in which the effects of hamster β1-integrin blocking antibody (Ha2/5) (BD Pharmingen) on neurite outgrowth were studied, 10 μg/mL antibody was added to the media. Cells were also cultured on 12-mm PDL/laminin-coated coverslips (Corning) (13,000 cells per coverslip) in 24-well plates. Cells were cultured for two days at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

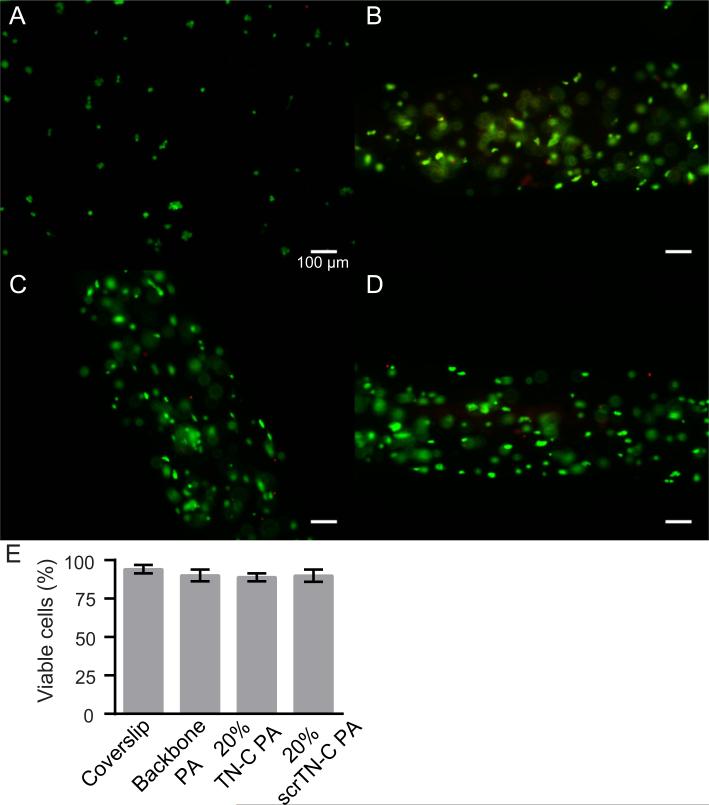

For cell viability experiments, after two days of culture, media was exchanged with PBS containing 2 μM calcein-AM (Life Technologies) and 100 ng/mL propidium iodide (Sigma) for 20 min at 37 °C. The gels were then rinsed with PBS and imaged with an inverted epifluorescent microscope (Zeiss). Live and dead cells were counted using the Cell Counter plug-in for ImageJ. A one-way ANOVA was performed and Tukey's multiple comparisons test was used to determine significance among various conditions.

For neurite outgrowth experiments, after two days of culture, gels were rinsed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. Gels were rinsed 3× with PBS then blocked with 10% normal goat serum and 0.1% triton X-100. Gels were incubated overnight with primary antibody in blocking solution (rabbit anti-β-III-tubulin IgG, 1/2000, Covance). Gels were rinsed with PBS 3× and blocked with 10% normal goat serum. Gels were incubated with secondary antibody for one hour (Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG, 1/100, Invitrogen). Fluorescent images of the gels were acquired with a laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss, Nicon), acquiring z-stacks containing 20–40 images per gel, with a z-dimension step size of 2 μm or 5.8 μm. The number of gels analyzed in data presented in Fig. 4 for backbone PA, 10% TN-C PA, 20% TN-C PA, and 50% TN-C PA were, 12, 12, 6, and 6, respectively. For data shown in Fig. 5, five gels not treated with β1-integrin blocking antibody and three gels treated with β1-integrin blocking antibody were analyzed for each condition. Neurites (not contacting other cells or neurites) were traced and measured using Simple Neurite Tracer, a plug-in for Image J, that enables the user to scroll between images in the z-stack while tracing neurites that move through multiple images. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows a montage of 26 images from an example z-stack, as well as examples of the neurite tracing procedure with Simple Neurite Tracer. A two-way ANOVA was used to evaluate the different gel compositions and the effects of β1-integrin blocking antibody. Tukey's multiple comparisons test was used to determine significant differences in gel compositions. Sidak's multiple comparisons test was used to determine significant differences between gels treated and not treated with β1-integrin blocking antibody.

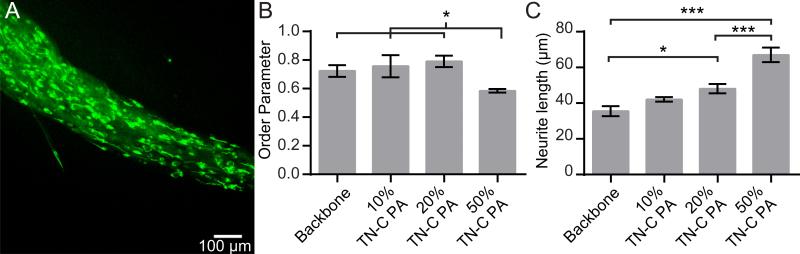

Fig. 4.

Neurite outgrowth from P19 embryonal carcinoma-derived neurons cultured for two days in PA gels. (A) Flattened z-stack image of immunolabeled cells (green: β-III-tubulin.) in 20% TN-C PA gel. (B) The order parameters of neurites in PA gels. (C) Average neurite lengths in PA gels. Error bars represent standard errors. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

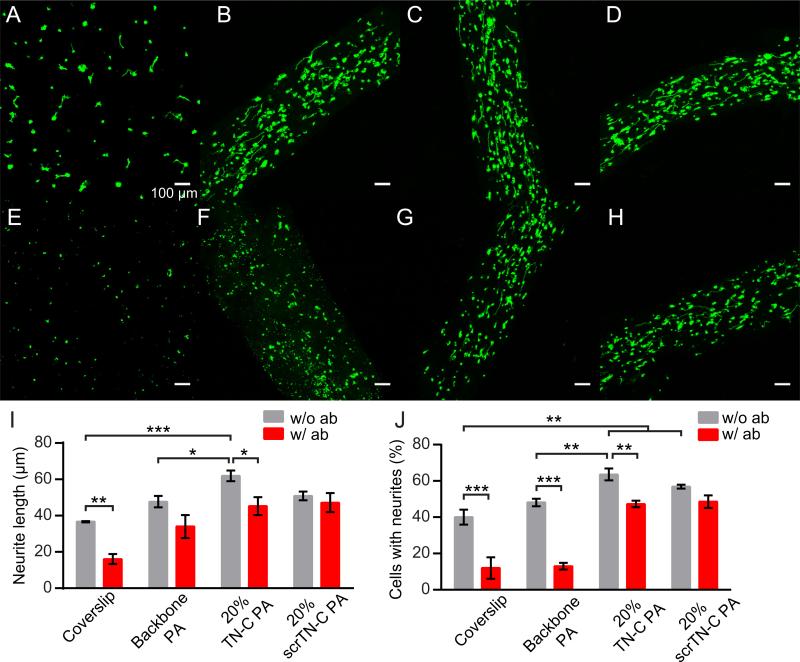

Fig. 5.

Neurite growth after two days on coverslips and PA gels. (A-H) Flattened z-stack images of immunolabeled cells (green: β-III-tubulin.). (A-D) Conditions without β1-integrin blocking antibody and (E-H) with 10 μg/mL β1-integrin blocking antibody. (A, E) Cells on PDL/laminin-coated coverslips. (B, F) Cells in backbone PA gels. (C, G) Cells in 20% TN-C PA gels. (D, H). Cells in 20% scrTN-C PA gels. (I) Average neurite lengths. (J) Percentage of β-III-tubulin-positive cells with neurites. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All scalebars correspond to 100 μm.

In order to quantify neurite alignment, the traces acquired in Simple Neurite Tracer were retraced in the NeuronJ plug-in for ImageJ software. The coordinates of each neurite were exported to a text file. A Matlab algorithm was written to determine the relative angle (θn) between each neurite segment and the longitudinal axis of the gel. These relative angles were used to calculate the order parameter (OP) with the following equation,

| (1) |

An order parameter of 1 indicates perfect alignment and 0 indicates random alignment. A one-way ANOVA was performed and Tukey's multiple comparisons test was used to determine significance between conditions.

2.5. PA coating of APTES-coated glass coverslips

12-mm glass coverslips were washed in 2% (vol/vol) micro-90 detergent (Sigma) for 30 min at 60 °C, then rinsed six times with distilled water. Coverslips were rinsed with ethanol, and then dried. An APTES coating on the glass was prepared similar to Peramo et al. [24]. Glass coverslips were plasma-etched with O2 for 30 s, then immediately incubated in a 2% (vol/vol) solution of APTES in ethanol for 15 min. Coverslips were rinsed twice with ethanol, then twice with water. Coverslips were dried, stored at 4 °C, and used within one month.

To create a thin gel coating, 3 μL of annealed 1% PA solutions were spread across the surface of an APTES-coated coverglass in a 24-well plate. For conditions composed of a mixture of PA, the backbone PA concentration was 0.75% (w/v) and the TN-C PA was 0.25% (w/v). 400 μL of gelling solution (150 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES) was added gently to the well for one min. After removing the gelling solution, the coverslips were rinsed three times with PBS with 1 mM CaCl2 before use.

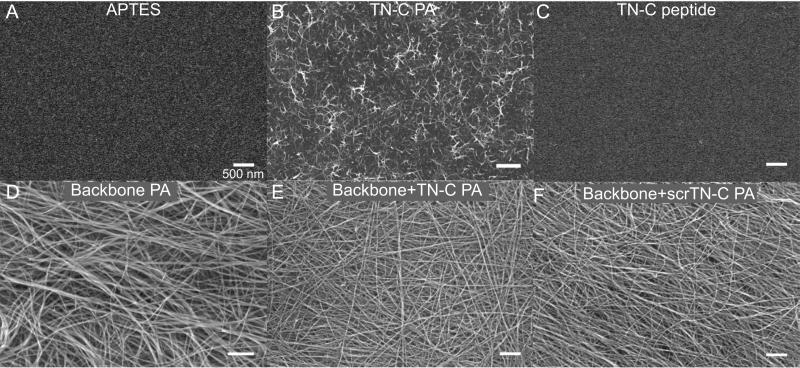

2.6. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of coatings

Coverslips were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series with a final rinse of 100% ethanol for 30 min. Coverslips were critical point dried (Tousimis, SAMDRI-795). Dry samples were placed on conductive adhesive tabs on pin stubs (Ted Pella). Samples were coated with 5 nm of osmium with an osmium plasma coater (Structure Probe, Inc.). Samples were imaged with a Hitachi S-4800 field emission scanning electron microscope at a typical accelerating voltage of 10 kV.

2.7. NPC migration assay

NPCs were cultured as previously described [25,26]. NPC isolation was performed in accordance with Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Briefly, ventricular zone tissue was dissected out from E13 mouse embryos and was mechanically and enzymatically dissociated into single cells and plated on un-tissue-culture-treated T75 flask in DMEM/F12 based media (containing 2% B27 supplement, 1% N2 supplement, 2 mM Glutamax, 1% P/S) supplemented with bFGF (20 μg/ml) and heparin (2 μg/mL). NPCs were passaged every four days and maintained up to five passages.

NPC neurospheres from passage 2–4, aged 3–4 days after passage were collected in Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged lightly for 15 s. The neurospheres were resuspended to a concentration of ~30–50 neurospheres per 75 μL. Solutions were removed from PA-coated coverslips and 75 μL of the neurosphere suspension was placed on the coverslips. Neurospheres were allowed to settle for 1 h before adding remaining media to the 24-well plates with the coverslips. After 4 days, samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min at 4 °C. Samples were imaged by phase contrast microscopy, and using ImageJ the areas occupied by each neurosphere were measured. The number of neurospheres analyzed for APTES-treated coverslips, TN-C PA, TN-C peptide, backbone PA, backbone PA with TN-C PA, and backbone PA with scrTN-C PA were, 21, 5, 6, 30, 29, 27, respectively. A one-way ANOVA was performed and Tukey's multiple comparisons test was used to determine significance between conditions.

2.8. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism v.6 software. One-way and two-way ANOVAs were performed (specified above) and Tukey's or Sidak's multiple comparisons tests were used to determine significant differences between conditions. Error bars in all figures represent standard errors.

3. Results

3.1. Materials characterization

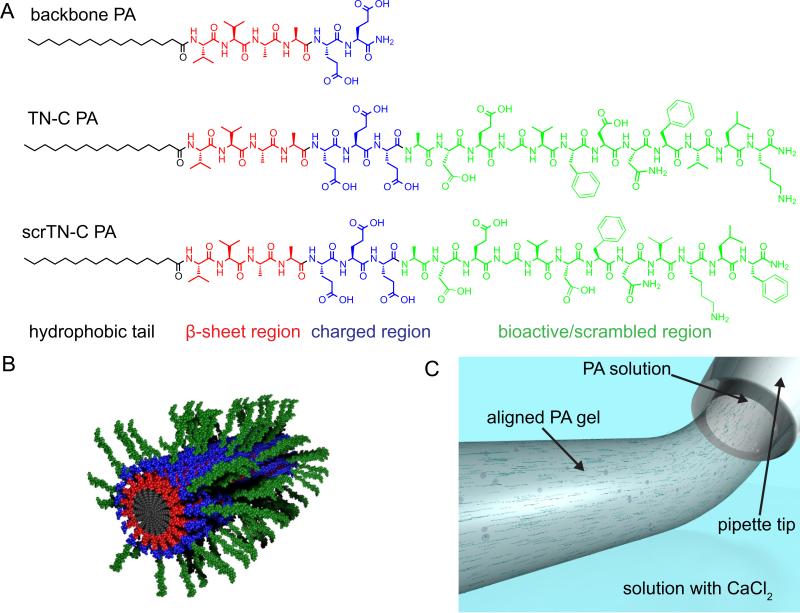

Gels containing aligned nanofibers composed of two different PAs were prepared using a recently developed approach (Fig. 1) [21]. One PA in the system contains a hydrophobic alkyl tail conjugated to the peptide sequence VVAAEE and is referred to as the backbone PA. This PA was selected because of its ability to form robust PA gels containing aligned nanofibers. The tenascin-C mimetic PA (TN-C PA) was synthesized with the same alkyl tail and peptide backbone sequence, followed by an extra glutamic acid for additional charge and the peptide sequence ADEGVFDNFVLK from tenascin-C which has been shown to promote neurite outgrowth [11]. The additional four amino acids in the tenascin-c sequence, ADEG, were included to act as a spacer between the charged region and the epitope, and because a peptide containing the ADEGVFDNFVLK sequence showed greater ability to promote neurite outgrowth than a peptide without the ADEG sequence in a previous report [13]. A peptide with the sequence ADEGVFDNFVLK but without the alkyl tail (TN-C peptide) was synthesized as well as a control version of the PA containing a scrambled epitope region (scrTN-C PA). In this control PA, the critical “FD” and “FV” amino acid positions were altered [11], resulting in the sequence ADEGVDFNVKLF.

Fig. 1.

Formation of gels with aligned PA nanofibers. (A) Chemical structures of PAs used to form the gels (B) Molecular graphics representation of nanofibers formed by co-assembly of bioactive and backbone PA molecules (the longer PA in the fiber displays the bioactive signal), (C) An illustration depicting the formation of a gel with aligned PA nanofibers by pipetting a PA solution through a salt solution containing CaCl2.

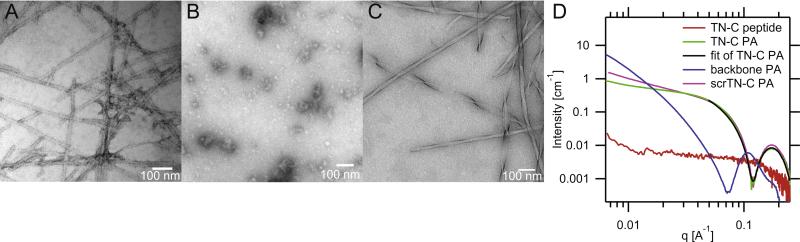

In order to verify that the TN-C PA would self-assemble into nanofibers in aqueous solutions, a 1% (w/v) solution in water, pH 7.4, was cast on a carbon film grid, then stained with uranyl acetate and examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 2A). The TN-C PA formed fairly uniform nanofibers with an average diameter of 13.5 ± 2.3 nm. TEMs of the TN-C peptide with the bioactive sequence ADEGVFDNFVLK, but lacking the backbone sequence and alkyl tail, demonstrated that the TN-C peptide did not form nanofibers (Fig. 2B). Rather, the peptide formed aggregates of various sizes without any regular morphology. TEM micrographs of the backbone PA reveal the formation of twisting, ribbon-like nanofibers with diameters ranging between 24 and 40 nm (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of PAs and TN-C peptide. Conventional TEM micrographs of (A) TN-C PA, (B) TN-C peptide, and (C) backbone PA, negatively stained with uranyl acetate. (D) SAXS scans and fit for 1 wt% solutions of PAs and peptide.

Small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) scans of 1 wt.% PA solutions in saline (150 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, pH 7.4) were obtained to confirm that the TN-C PA forms nanofibers (Fig. 2D). The low q region of the SAXS curve (q < 10-1 Å) of TN-C PA had a slope of −0.71, which indicates that a cylindrical fiber morphology is the dominant nanostructure (a slope of −1 is indicative of cylindrical structures). Furthermore, a fit using a cylindrical core-shell model was able to closely match the TN-C PA curve, confirming the nanofiber morphology. The similarity between the TN-C PA and scrTN-C PA curves demonstrates that they have similar nanofiber morphologies. In contrast, the SAXS curve of the TN-C peptide without the backbone sequence and alkyl tail reveals the absence of any defined nanoscale structure. For the backbone PA, the slope of the SAXS curve in the low q region is −2.27, corresponding to a flat nanostructure (a slope of −2 is indicative of flat structures), which matches the morphology of the nanofibers observed in TEM micrographs.

3.2. Neurite outgrowth in aligned PA gels

Next, we evaluated the potential of gels containing TN-C PA to support cell viability and to promote the growth of aligned neurites by culturing neurons, differentiated from P19 embryonal carcinoma cells, in the PA gels for two days. In all of the gel compositions tested, cell viability was high (approximately 90%) and was similar to cell viability on PDL/laminin-coated coverslips (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Cell viability in PA gels after two days of culture. (A) P19-derived neurons on a PDL/laminin coverslip, (B) in backbone PA gel, (C) in backbone PA and 20% TN-C PA gel, and (D) in backbone PA and 20% scrTN-C PA gel. Living cells are labeled green (calcein-AM) and dead cells are labeled red (propidium iodide). Scale bars: 100 μm. (E) The percentage of cells that were viable for each condition.

We observed that neurites had a strong tendency to grow in the direction of the aligned nanofiber gels, based on Order Parameters (OPs) calculated from the neurite traces (see Section 2 for details). Neurite alignment in gels composed of backbone PA and up to 20% TN-C PA was high, with OPs from 0.72 to 0.79 (Fig. 4B). However, there was a significant decrease in OP (0.58) when the TN-C PA content was 50% of the total PA. This is likely due in part to the reduction of the amount of backbone PA, which was selected because of its ability to form robust aligned gels. It may also be due to a change in nanostructure of the fibers composed of the mixture of PAs that occurs during the annealing process. The average neurite length significantly increased in gels with 20% and 50% TN-C PA, relative to gels composed of only the backbone PA, and the effect increased as the percentage of TN-C PA increased (Fig. 4C). Based on these results, gels composed of 20% TN-C PA were further studied, since this concentration of TN-C PA increased neurite outgrowth but did not decrease neurite alignment.

Next, we compared neurite growth in TN-C gels with growth on coverslips and in gels with scrTN-C PA. Neurite alignment in TN-C PA gels (OP = 0.68) was similar to scrTN-C PA gels (OP = 0.71). Neurite length in TN-C gels was significantly greater compared to coverslips (69% greater) and backbone PA gels (30% greater), though not significantly greater than scrTN-C PA (Fig. 5I). In contrast, neurite length in scrTN-C gels was found not to be significantly different from the other gel compositions or coverslips, and in fact was similar to the mean length in backbone PA gels (50.8 μm vs. 47.7 μm, respectively). We also found that in TN-C PA gels, the percentage of β-III-tubulin-positive cells with neurites was slightly (but not significantly) higher than in scrTN-C PA gels while it was significantly higher than on coverslips and backbone PA gels (Fig. 5J). In contrast, the percentage of cells with neurites in scrTN-C PA gels was not significantly different than in backbone PA gels.

Since the tenascin-C-derived peptide sequence was reported to interact with β1 integrin, we also tested neurite growth in gels treated with 10 μg/mL β1-integrin blocking antibody (β1-ab) (Fig. 5E-H), which has previously been shown to block neurite outgrowth enhancement by the peptide [12]. Addition of β1-ab resulted in significant reductions in the percentage of β-III-tubulin-positive cells with neurites on coverslips and in backbone PA and TN-C PA gels, but not in scrTN-C PA gels (Fig. 5J). Average neurite lengths also significantly decreased on coverslips and in TN-C PA gels, but not in backbone PA gels and scrTN-C PA gels (Fig. 5I).

3.3. Neurosphere-derived cell migration on PA gel coatings

In order to assess the ability of PA gels to support NDC migration, a thin coating of gel was formed on aminopropyltriethoxysi-lane (APTES)-treated coverslips. The APTES treatment was used to create a positive layer on the glass surface, so that the net-negatively charged PAs would adsorb onto the positively charged glass surface. PA coatings on the APTES-treated glass were then visualized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). SEM micrographs reveal that the TN-C PA formed a coating of short nanofibers less than one μm in length (Fig. 6B), while gelation of solutions containing the backbone PA formed dense coatings of long nanofibers (Fig. 6D-F). The difference in coating density is likely due to greater electrostatic attraction between the positively charged glass surface and the negative surface charge on backbone PA nanofibers, which are terminated by two glutamates that carry a negative charge at physiological pH. The morphological difference between the TN-C PA fibers and the backbone PA fibers is likely due to variations in the order and strength of hydrogen bonding between molecules within the nanofibers. Coatings formed from mixed solutions of backbone PA and TN-C PA (25% TN-C PA) or scrTN-C PA (25% scrTN-C PA) (Fig. 6E, F) closely resembled those formed by backbone PA alone. As expected, the TN-C peptide did not form any observable nanostructures on the APTES-coated coverslips (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

SEM micrographs of peptide and PA coatings (as labeled) on APTES-treated glass coverslips. (A) APTES-treated coverslip control. (E, F) The PA mixtures contain 25% of either TN-C PA or scrTN-C PA. Scalebars correspond to 500 nm.

Embryonic mouse neural progenitor cell-derived neurospheres were cultured for four days on the surfaces described in Fig. 5 and on PDL coverslips. On PDL coverslips, neurospheres readily attached and cells migrated out from the neurosphere to distances of several hundred micrometers (Fig. 7A). In contrast, only a small fraction of the neurospheres seeded on APTES-coated glass attached to the surface, and those that attached remained spherical (Fig. 7B). The low rate of attachment and lack of spreading was similar on TN-C PA and peptide coatings (Fig. 7C, D). Neurospheres attached with much greater frequency on coatings containing the backbone PA and cells migrated out from the neurosphere (Fig. 7E, F, G). The coatings containing the backbone PA (Fig. 6D, E, F) all show dense networks of long nanofibers, which may aid in cell attachment and migration. The average area covered by cells from a neurosphere was 2.9 times greater on backbone PA coatings compared to APTES-treated glass (Fig. 7H). Inclusion of the TN-C PA with the backbone PA significantly increased the area of spreading by 41% compared to the backbone PA alone. Cell migration on coatings containing backbone PA with scrTN-C PA were not significantly different than on backbone PA alone or mixtures of backbone PA with TN-C PA.

Fig. 7.

(A-G) Representative NPC neurospheres cultured on PDL coverslips, APTES coverslips, PA- and peptide-coated coverslips for four days. Scalebars: 100 μm. (H) The average area of neurospheres on coatings after four days, normalized to the average area of neurospheres on APTES-treated glass. Error bars represent standard errors. **P < 0.01.

4. Discussion

This work demonstrates that a peptide sequence taken from tenascin-C can be incorporated into a self-assembling PA nanofiber system while retaining its neurite growth-promoting properties. An interesting benefit of the self-assembling nature of this material is the ability to transition from a solution to gel upon exposure to physiological divalent cations, like Ca2+. Combined with the ability to align the nanofibers, we were able to trap neurons suspended in a PA solution within an aligned gel upon exposure to Ca2+ ions. Cells encapsulated in the gels remained viable and grew neurites that aligned with the longitudinal axis of the gel.

Inclusion of the tenascin-C PA in gels effectively signaled neurons to increase their neurite length and increase the percentage of β-III-tubulin-positive cells relative to backbone PA gels. Addition of the scrTN-C PA in gels did not significantly increase neurite length or the percentage of β-III-tubulin-positive cells with neurites, relative to backbone PA gels. However, in these measurements TN-C PA gels were not significantly different than scrTN-C PA gels. When gels were treated with β1-integrin blocking antibody, neurite length and the percentage of β-III-tubulin-positive cells with neurites significantly decreased in TN-C PA gels, but not in scrTN-C PA gels. Taken together, these results suggest that the TN-C PA is effective at increasing the number of cells with neurites and their length and the effect is at least in part mediated through β1-integrin interaction. However, since the scrTN-C PA was not significantly different from TN-C PA or backbone PA, the dependence on peptide sequence is not entirely resolved.

One of the primary goals of the development of this PA was to create a material that could be used to improve functional recovery in spinal cord injury by injecting the PA in solution into the acutely injured tissue. In previous work, we demonstrated that injection of a laminin-mimetic PA with the sequence IKVAV improved functional performance as measured by the BBB scale in rodent models of acute spinal cord injury [19]. In a recently reported paper, it was shown that the IKVAV PA increased activation of β1 integrin following injection at the injury site, as measured by HUTS-4 antibody fluorescent labeling in tissue one week post-injection [27]. This motivated the development of the TN-C PA, since the peptide had been shown to act through β1 integrin signaling to promote neurite outgrowth. Indeed, injection of the TN-C PA into the acute injury resulted in a significant increase in BBB score from 5.58 in the vehicle-treated animals to 10.2 in TN-C PA-treated animals [27]. The in vitro results shown here suggest that the improvement in BBB score found previously may be a consequence of improved neurite growth in the injury or the ability of the PA to aid in cell migration, which may also be critical for recovery in the injured cord.

A second main objective was to develop a PA capable of promoting migration of cells derived from neural progenitor cells. We envisioned using a material with both physical directional cues of aligned fibers along with biochemical cues that were present in native migratory channels like the rostral migratory stream. A material capable of guiding cells derived from neural progenitors or stem cells could be used to direct native or transplanted cells to regions of neuronal loss. Tenascin-C is expressed in the RMS and is presented to migrating neuroblasts on the surfaces of astrocytes [9]. At the same time, β1 integrin is known to play a role in neural migration [28,29]. This work confirms our hypothesis that nanofibers presenting a tenascin-C-derived β1 integrin binding sequence would increase NPC-derived cell migration. Neurospheres attached and cells migrated on all gel coatings that included the backbone PA. A significant increase in cell migration occurred on coatings composed of PA mixtures containing both the backbone PA and the TN-C PA compared to backbone PA alone. In contrast, there was not a significant difference in migration between the coatings of backbone PA alone and mixtures of backbone PA with scrTN-C PA.

Here again, addition of the TN-C PA with the backbone PA resulted in a significant effect, while the scrTN-C PA did not, but there were not significant differences between TN-C PA and scrTN-C PA when directly compared. This provides additional support to the possibility that there may be some factor that is not sequence-specific contributing to the observed effects. One possibility is that the changed sequence found in the scrTN-C PA retains some of the bioactivity of the tenascin-C-derived sequence. In the original work discovering the bioactivity of the VFDNFVLK sequence from tenascin-C, control peptides were tested in which the sequence was not scrambled, instead certain amino acids were substituted [11]. The control peptide for which the most data was presented, and which was used in further work [12], was VSPNGSLK. In this peptide, four of the amino acids have been changed, one of which was changed to a proline. These changes may have eliminated any bioactivity, while the rearrangement of the amino acids in the scrTN-C PA may have resulted in partial retention of bioactivity. Additional evaluation of variants would be necessary to fully elucidate the role of sequence specificity.

5. Conclusions

We have shown that a bioactive peptide sequence from the ECM glycoprotein tenascin-C can be incorporated into self-assembling peptide amphiphiles capable of forming nanofibers. Gels with the TN-C mimetic PA promoted neurite outgrowth, which may play a role in the material's ability to promote functional recovery after spinal cord injury. The functionality of this material also extends to the enhancement of NPC-derived cell migration. The ability to promote migration, combined with the ability to align PA nanofibers, opens the possibility of using this material to guide endogenous or transplanted neural stem cells to repopulate dysfunctional areas of the brain.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Significance.

Tenascin-C is an important extracellular matrix molecule in the nervous system and has been shown to play a role in regenerating the spinal cord after injury and guiding neural progenitor cells during brain development, however, minimal research has been reported exploring the use of biomimetic biomaterials of tenascin-C. In this work, we describe a selfassembling biomaterial system in which peptide amphiphiles present a peptide derived from tenascin-C that promotes neurite outgrowth. Encapsulation of neurons in hydrogels of aligned nanofibers formed by tenascin-C-mimetic peptide amphiphiles resulted in enhanced neurite outgrowth. Additionally, these peptide amphiphiles promoted migration of neural progenitor cells cultured on nanofiber coatings. Tenascin-C biomimetic biomaterials such as the one described here have significant potential in neuroregenerative medicine.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Biomedical Imaging And Bioengineering Award Number 5R01EB003806-07 and by the Center for Regenerative Nanomedicine at the Simpson Querrey Institute for BioNanotechnology at Northwestern. J.E.G. received postdoctoral support from the National Institutes of Health Award Number F32EB007131. Peptide synthesis was performed in the Peptide Synthesis Core Facility and cell culture was performed in the Nano-medicine Cleanroom of the Simpson Querrey Institute at Northwestern University. The U.S. Army Research Office, the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, the Department of Energy, the Frederick S. Upton Foundation and Northwestern University provided funding to develop these facilities. Imaging was performed at the Northwestern University Center for Advanced Microscopy generously supported by NCI CCSG P30 CA060553 awarded to the Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center. SEM was performed at the Electron Probe Instrumentation Center of the NUANCE Center at Northwestern University, which is supported by NSF-NSEC, NSF-MRSEC, Keck Foundation, the State of Illinois, and Northwestern University. Use of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. The authors acknowledge Tammy McGuire for isolation of neural progenitor cells and Dr. Steven Weigand for assistance with SAXS experiments.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2016.04.010.

References

- 1.Hubbell JA. Bioactive biomaterials. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 1999;10:123–129. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(99)80021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt CE, Leach JB. Neural tissue engineering: strategies for repair and regeneration. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2003;5:293–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.5.011303.120731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matson JB, Zha RH, Stupp SI. Peptide self-assembly for crafting functional biological materials. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2011;15:225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.cossms.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Webber MJ, Kessler JA, Stupp SI. Emerging peptide nanomedicine to regenerate tissues and organs. J. Intern. Med. 2010;267:71–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin H, Jo S, Mikos AG. Biomimetic materials for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4353–4364. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00339-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collier JH, Segura T. Evolving the use of peptides as components of biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2011;32:4198–4204. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu Y-M, Cristofanilli M, Valiveti A, Ma L, Yoo M, Morellini F, Schachner M. The extracellular matrix glycoprotein tenascin-C promotes locomotor recovery after spinal cord injury in adult zebrafish. Neuroscience. 2011;183:238–250. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Winterbottom JK, Schachner M, Lieberman AR, Anderson PN. Tenascin-C expression and axonal sprouting following injury to the spinal dorsal columns in the adult rat. J. Neurosci. Res. 1997;49:433–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas LB, Gates MA, Steindler DA. Young neurons from the adult subependymal zone proliferate and migrate along an astrocyte, extracellular matrix-rich pathway. Glia. 1996;17:1–14. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199605)17:1<1::AID-GLIA1>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcion E, Halilagic A, Faissner A, ffrench-Constant C. Generation of an environmental niche for neural stem cell development by the extracellular matrix molecule tenascin C. Development. 2004;131:3423–3432. doi: 10.1242/dev.01202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meiners S, Nur-e-Kamal MS, Mercado ML. Identification of a neurite outgrowth-promoting motif within the alternatively spliced region of human tenascin-C. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:7215–7225. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07215.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mercado MLT, Nur-e-Kamal A, Liu H-Y, Gross SR, Movahed R, Meiners S. Neurite outgrowth by the alternatively spliced region of human tenascin-C is mediated by neuronal alpha7beta1 integrin. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:238–247. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4519-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed I, Liu HY, Mamiya PC, Ponery AS, Babu AN, Weik T, Schindler M, Meiners S. Three-dimensional nanofibrillar surfaces covalently modified with tenascin-C-derived peptides enhance neuronal growth in vitro. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2006;76:851–860. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sever M, Mammadov B, Guler MO, Tekinay AB. Tenascin-C mimetic peptide nanofibers direct stem cell differentiation to osteogenic lineage. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15:4480–4487. doi: 10.1021/bm501271x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartgerink J, Beniash E, Stupp S. Self-assembly and mineralization of peptide-amphiphile nanofibers. Science. 2001;294:1684–1688. doi: 10.1126/science.1063187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webber MJ, Berns EJ, Stupp SI. Supramolecular nanofibers of peptide amphiphiles for medicine. Isr. J. Chem. 2013;53:530–554. doi: 10.1002/ijch.201300046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beniash E, Hartgerink JD, Storrie H, Stendahl JC, Stupp SI. Self-assembling peptide amphiphile nanofiber matrices for cell entrapment. Acta Biomater. 2005;1:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silva GA, Czeisler C, Niece KL, Beniash E, Harrington DA, Kessler JA, Stupp SI. Selective differentiation of neural progenitor cells by high-epitope density nanofibers. Science. 2004;303:1352–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1093783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tysseling-Mattiace VM, Sahni V, Niece KL, Birch D, Czeisler C, Fehlings MG, Stupp SI, Kessler JA. Self-assembling nanofibers inhibit glial scar formation and promote axon elongation after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:3814–3823. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0143-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberger JE, Berns EJ, Bitton R, Newcomb CJ, Stupp SI. Electrostatic control of bioactivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011;50:6292–6295. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berns EJ, Sur S, Pan L, Goldberger JE, Suresh S, Zhang S, Kessler JA, Stupp SI. Aligned neurite outgrowth and directed cell migration in self-assembled monodomain gels. Biomaterials. 2014;35:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.09.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang S, Greenfield MA, Mata A, Palmer LC, Bitton R, Mantei JR, Aparicio C, de la Cruz MO, Stupp SI. A self-assembly pathway to aligned monodomain gels. Nat. Mater. 2010;9:594–601. doi: 10.1038/nmat2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacPherson P, McBurney M. P19 embryonal carcinoma cells: a source of cultured neurons amenable to genetic manipulation. Methods. 1995;65:1093–1099. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peramo A, Albritton A, Matthews G. Deposition of patterned glycosaminoglycans on silanized glass surfaces. Langmuir. 2006;22:3228–3234. doi: 10.1021/la051166m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reynolds BA, Weiss S. Generation of neurons and astrocytes from isolated cells of the adult mammalian central nervous system. Science. 1992;255:1707–1710. doi: 10.1126/science.1553558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vescovi AL, Reynolds BA, Fraser DD, Weiss S. BFGF regulates the proliferative fate of unipotent (neuronal) and bipotent (neuronal/astroglial) EGF-generated CNS progenitor cells. Neuron. 1993;11:951–966. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90124-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan L, North HA, Sahni V, Jeong SJ, McGuire TL, Berns EJ, Stupp SI, Kessler JA. Beta1-Integrin and integrin linked kinase regulate astrocytic differentiation of neural stem cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacques TS, Relvas JB, Nishimura S, Pytela R, Edwards GM, Streuli CH, ffrench-Constant C. Neural precursor cell chain migration and division are regulated through different beta1 integrins. Development. 1998;125:3167–3177. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.16.3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leone DP, Relvas JB, Campos LS, Hemmi S, Brakebusch C, Fassler R, Ffrench-Constant C, Suter U. Regulation of neural progenitor proliferation and survival by beta1 integrins. J. Cell. Sci. 2005;118:2589–2599. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.