Abstract

Research in the past decade has documented that financial exploitation of older adults has become a major problem and Psychology is only recently increasing its presence in efforts to reduce exploitation. During the same time period, Psychology has been a leader in setting best practices for the assessment of diminished capacity in older adults culminating in the 2008 ABA/APA joint publication on a handbook for psychologists. Assessment of financial decision making capacity is often the cornerstone assessment needed in cases of financial exploitation. This paper will examine the intersection of financial exploitation and decision making capacity; introduce a new conceptual model and new tools for both the investigation and prevention of financial exploitation.

Financial exploitation—the misappropriation of an older adult’s money and/or property—is commonly discussed in terms of thefts, scams, and abuse of trust (Conrad, Iris, Ridings, Langley, & Wilber, 2010). Financial exploitation is increasing dramatically among older adults (Lichtenberg, Stoltman, Ficker, Iris, & Mast, 2015a), and yet psychology, like other disciplines involved in gerontology, has only recently begun to address this aspect of elder abuse. Financial exploitation is the second most common form of elder abuse (after emotional abuse), with an estimated prevalence rate of 5% each year (Acierno et al., 2010), and much of this financial exploitation of older adults is related to Alzheimer’s disease and its impact on financial capacity defined as a multidimensional construct (Marson et al., 2001) that ranges from paying bills to making major financial decisions. Financial decision making capacity; only one of the domains of financial capacity, will be the domain focused on in this paper. Although the field of psychology has not yet focused heavily on financial exploitation, financial exploitation is directly related to an area of work psychologists are very familiar with; diminished capacity and specifically financial incapacity: the lack of requisite skills to make informed decisions about financial matters (see ABA-APA, 2008). Indeed financial incapacity is often a cornerstone assessment in cases of financial exploitation. Although research on financial incapacity has examined the cognitive issues linked to a decrease in financial abilities (Marson et al., 2001), it has rarely considered financial exploitation. This paper will attempt to tie together psychological and neurocognitive aspects of financial exploitation with psychological and neurocognitive aspects of financial incapacity. The paper will briefly review separately the research in both financial exploitation and financial capacity, and then introduce a new conceptual model to tie this areas together, and introduce new assessment procedures as well. Finally, clinical and societal implications will be examined.

It is important to underscore the ethical principles involved in the call for elder justice, which Nerenberg, Davies and Navarro (2012) defines as older adults’ fundamental right to live free from abuse, neglect, and exploitation. While it is vitally important that older adults be protected from financial exploitation, it is equally important that they maintain financial autonomy. Both under- and overprotection of older adults can have damaging consequences. Under-protection of older adults can lead to gross financial exploitation and affect every aspect of the older adult’s life, including the ability to pay for necessary services. The dilemma is that overprotection can be equally costly. Many older adults strongly desire autonomy and control, such that unnecessarily limiting autonomy can lead to increased health problems and shortened longevity. Ageism—the tendency to view older adults in negative stereotypes (Hinrichsen, 2015)—exacerbates the tendency to overprotect older adults; ironically, ageism and the desire to “protect” older adults can result in financial exploitation by relatives and acquaintances who seem to have only the older adult’s interests in mind when they step in to “help.” Lichtenberg (2011) highlighted the deleterious effects of limiting autonomy when it was unnecessary and indeed these included exposing older adults to an increased risk of financial exploitation.

Financial Exploitation

Four recent random-sample studies of community-dwelling older adults have documented alarming rates of financial exploitation and its correlates; a fifth study offered a new way to classify financial exploitation. For the most part, these studies gathered data on abuse of trust, coercion, and financial entitlement. Acierno et al. (2010) report that 5.2% of all respondents had experienced financial exploitation by a family member during the previous year; 60% of the mistreatment consisted of family members’ misappropriation of money. The authors also examined a number of demographic, psychological, and physical correlates of reported financial exploitation. Only two variables—deficits in the number of activities of daily living (ADLs) the older adult could perform and nonuse of social services—were significantly related to financial exploitation.

Laumann, Leitsch, and Waite (2008) found that 3.5% of their sample had been victims of financial exploitation during the previous year. Younger older adults, ages 55–65, were the most likely to report financial exploitation. African Americans were more likely than Non-Hispanic Caucasians to report financial exploitation, while Latinos were less likely than Non-Hispanic Caucasians to report having been victimized. Finally, participants with a romantic partner were less likely to report financial exploitation.

Beach, Schulz, Castle, and Rosen (2010) found that 3.5% of their sample reported having experienced financial exploitation during the previous six months, and almost 10% had at some point since turning 60. The most common experience was signing documents the participant did not fully understand. The authors found that, directly related to theft and scams, 2.7% of their subjects believed that someone had tampered with their money within the previous six months. African Americans were more likely to report financial exploitation than were Non-Hispanic Caucasians, and depression and ADL deficits were other correlates of financial exploitation.

Lichtenberg, Stickney, and Paulson (2013) investigated older adults’ experience of fraud, defined as financial losses—other than by robbery or theft—inflicted by another person. This was the first population-based study that gathered prospective data to predict financial exploitation of any kind. The sample consisted of 4,400 older adults who participated in a Health and Retirement Survey substudy, the 2008 Leave-Behind Questionnaire. The prevalence of fraud across the previous five years was 4.5%, and among measures collected in 2002, age, education, and depression were significant predictors of fraud. Using depression and social-needs fulfillment to determine the most psychologically vulnerable older adults, Lichtenberg and colleagues found that fraud prevalence in those with the highest rates of depression and lowest social-needs fulfillment was three times higher (14%) than the rest of the sample (4.1%; χ2=20.49; p<.001).

Jackson and Hafemesiter (2012) compared the experience of pure financial exploitation with hybrid financial exploitation, in which psychological abuse, physical abuse, or neglect is found along with financial exploitation. In cases of hybrid financial exploitation, older adults were less healthy and more likely to be abused by those who cohabited with them. The older adult victims were also more likely to have Alzheimer’s disease in cases of hybrid exploitation. This important research highlights the variability and heterogeneity of financial exploitation of older adults, and leads directly to the links of financial exploitation to Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease and Financial Abilities

In recent years, the Alzheimer’s Association in partnership with the National Institute on Aging updated the clinical criteria for Alzheimer’s disease (McKhann et al., 2011). There is now general agreement that in the preclinical phase of Alzheimer’s disease, the biological processes involved can begin decades before clinical symptoms appear (Sperling et al., 2011). The importance of the preclinical phase and the mild cognitive impairment (MCI) phase that follows (Albert et al., 2011) is that older adults are slowly and insidiously becoming more vulnerable cognitively, and often this decline goes unrecognized by both loved ones and professionals. One of the earlier changes that can accompany cognitive decline is a decrease in financial decision making abilities.

Plassman et al. (2008) used a subsample of the nationally representative Health and Retirement Study to estimate the prevalence of cognitive impairment, both with and without Alzheimer’s disease in the U.S. The baseline data included more than 1,700 older adults, and the longitudinal study 856 individuals age 71 and older. Baseline data reveal that in 2008, an estimated 5.4 million people age 71 and older had cognitive impairment, akin to Mild Cognitive Impairment, and an additional 3.4 million had dementia. The findings are striking, in that they show a much higher rate of cognitive impairment than found in any other sample. This dramatic increase in the older-adult population in the U.S. means that the number of individuals with cognitive impairment will almost triple in the next 35 years (Hebert, Scherr, Bienias, Bennett, & Evans, 2003).

The impact of Alzheimer’s disease on financial capacity (Marson, 2001) threatens financial autonomy. For many years, Marson and his colleagues have investigated how major neurocognitive disorders impact financial capacity, which they define as the ability to manage money and financial assets in ways that are consistent with one’s values or self-interest. Stiegal (2012) explains how financial capacity and financial exploitation are connected, in that older adults’ vulnerability is twofold: (a) the potential loss of financial skills and financial decision making and (b) the inability to detect—and therefore prevent—financial exploitation.

Marson (2001) demonstrated that financial capacity is closely linked to stage of Alzheimer’s disease. In a group of individuals in the mild stage of Alzheimer’s, the authors found that 13% were fully capable of financial decision making and another 37% were marginally capable. In contrast, few in the moderate stage were rated as capable. In the case of marginally capable individuals, it is clear that being in the mild stage of Alzheimer’s disease makes an older adult vulnerable, however, 50% of older adults with mild stage Alzheimer’s disease were judged to be capable or marginally capable of financial decision making.

Sherod et al. (2009) investigated the neurocognitive predictors of financial capacity across 85 healthy normal older adults, 113 older adults with MCI, and 43 older adults with mild Alzheimer’s disease. Interestingly, arithmetic was the single best predictor of financial decision making capacity. When it came to self-assessment, Okonkwo et al. (2009) found that in their study, even those older adults in the earlier stages of cognitive decline—with only mild cognitive impairment—were more likely to overestimate their cognitive skills than normal controls. In contrast, financial decision making remained intact among those with mild cognitive impairment, relative to normal controls. Taken together, these results underscore the idea that while mild cognitive impairment makes older adults more vulnerable, it does not inevitably rob them of financial decision making abilities.

Several newer studies have investigated actual financial decision making in couples in which one person shows cognitive decline. Findings demonstrate the value of an assessment tool that offers protection where needed, but also supports autonomy wherever possible. Over a 10-year period, Hsu and Willis (2013) examined financial management in couples in which one party had cognitive deficits and found that cognitive impairment—and not cognitive change—was related to greater financial difficulties. Indeed, difficulties with money often preceded the turning over of financial decision making from the cognitively impaired spouse to the non-impaired spouse. Nevertheless, 33% of respondents in the study continued to be the primary financial decision maker, despite having cognitive scores in the range of Mild Alzheimer’s disease.

Boyle et al. (2012) and Boyle (2013) examined how cognitive abilities before the onset of Alzheimer’s disease predict financial decision making five years later, and found that more rapid cognitive decline leads to poorer decision-making abilities (using hypothetical mutual-fund options), even in participants with mild cognitive impairment. These results are consistent with Marson et al.’s (2009) research on financial capacity. Marson (2001; also see Marson et al., 2009) argues that the impact of, Alzheimer’s disease on financial decision making capacity is one of the biggest challenges to financial autonomy.

Although cognitive functioning is an important predictor of financial decision making capacity, other factors may influence financial decision making abilities. Boyle (2013) points out that financial decision making capacity differs from executional capacity (e.g., the ability to manipulate money, pay bills, and understand and maintain an accurate checkbook). In nearly 25% of the couples studied, the person with Alzheimer’s disease retained decisional capacity, even in the absence of executional capacity. Boyle’s findings on individual differences underscore the ethical tension: One must always be aware of the fundamental tension between autonomy (self-determination) and protection (beneficence; Moberg & Kniele, 2006; Moye & Marson, 2007). It can be tempting to rely on generalized findings, such as the fact that older adults are at risk for financial scams and theft, and apply them in each case, no matter the circumstances, to protect the older adult.

There is little overlap between recent research on financial exploitation and financial capacity. Financial-exploitation research, funded primarily by the National Institute of Justice, has focused on determining the prevalence and subtypes of exploitation. This requires population-based random samples and telephone interviews. Since most telephone interviews exclude persons with Alzheimer’s disease, the data are frequently confusing—for instance, is financial exploitation actually more common among the near old (55–64 years) than among older adults? In contrast, Jackson and Hafemesiter (2012) did not use a random population-based sample; instead, they examined records from Utah’s Adult Protective Services, the state agency responsible for investigating elder abuse. Jackson and Hafemeister determined that older persons with Alzheimer’s disease were more likely to experience more than one type of abuse and to lose, on average, twice as much money per case of financial exploitation as those without dementia. In contrast, financial decision making capacity research has focused on older people with Alzheimer’s disease, but has not investigated real-world financial transactions or exploitation. Kemp and Mosqueda (2005) discuss the lack of validated measures to evaluate elder financial decision making abilities and the importance of assessment by a qualified expert. Shivapour, Nguyen, Cole, and Denburg (2012) highlight the need for well-validated measures of decision-making capacity in older adults that have been tailored to specific decisions.

In sum, the links between financial exploitation, capacity, and Alzheimer’s disease are clear—yet they remain disconnected in actual practice. Many cases of financial exploitation have a root cause in impaired decision making abilities. Dong (2014) concluded that decision-making capacity is the cornerstone assessment in cases of elder abuse, including financial exploitation. In the next section, conceptual and empirical approaches will be introduced that may bring these areas together. Conceptual models are grounded in the previous work of both financial exploitation and financial decision making capacity and includes their linkages to Alzheimer’s disease.

The Person-centered Approach to Assessment in Persons with Alzheimer’s disease

In the 1970s and 1980s interest in capacity assessment went up following significant changes in the laws that determine competency. Under the new laws, functional testing and not just the presence of neurocognitive and mental health diagnoses replaced the mere presence of one or more mental health diagnoses as the legal standards for incompetence across the U.S. (see Appelbaum & Grisso, 1988, for review). Appelbaum and Grisso (1988) examined the legal standards used by states to determine incapacity and identified the decision-making abilities or intellectual factors involved in making informed decisions: choice, understanding, appreciation, and reasoning. These kernel intellectual factors have been reiterated as fundamental aspects of decisional abilities (ABA/APA, 2008). Although originally outlined for medical decision making, the same intellectual factors apply to financial decisions.

Specifically, the older adult must be capable of clearly communicating his or her choice. Understanding is the ability to comprehend the nature of the proposed decision and provide some explanation or demonstrate awareness of its risks and benefits. Appreciation refers to the situation and its consequences, and often involves their impact on both the older adult and others; Appelabum and Grisso (1988) contend that the most common causes of impairment in appreciation are lack of awareness of deficits and/or delusions or distortions. Reasoning includes the ability to compare options—for instance, different treatment options in the case of health decision making—as well as the ability to provide a rationale for the decision or explain the communicated choice.

Flint, Sudore, and Widera (2012) found that impaired financial decision making is linked not only to cognitive impairment, but also to the behavioral and psychological symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease including lack of awareness and delusional thinking. While the financial-exploitation literature has focused on risk factors for financial abuse and definitions for financial exploitation, the financial-capacity literature has emphasized financial knowledge and skills and, to a lesser extent, financial decision making. Yet in the context of a specific financial decision, it is essential to determine whether the older adult’s judgment is authentic and the integrity of his or her financial-decisional abilities intact.

The person-centered approach to work with older adults who suffer from Alzehiemer’s disease helps to support autonomy in these individuals (Fazio, 2013). This approach aims to build on the individual’s strengths and honor a person’s values and his or her choices and preferences (Fazio, 2013). Some of the method’s underlying assumptions (Mast, 2011) are that (a) people are more than the sum of their cognitive abilities, (b) traditional approaches overemphasize deficits and underemphasize strengths, and (c) it is important to understand the person’s subjective experience, particularly in relation to their positive and negative reactions to others’ behavior. Whitlach (2013) emphasizes the importance of persons with Alzheimer’s disease continuing to have choice, and states that even people scoring well into the impaired range on the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) can provide valid and reliable responses. Mast (2011) describes a new approach to the assessment of persons with Alzheimer’s disease the Whole Person Dementia Assessment, which seeks to integrate person-centered principles with standardized assessment techniques.

We aimed to expand the conceptual model of decision-making abilities described by Appelbaum and Grisso (1988) and incorporate the Whole Person Assessment approach. Person-centered principles allow for the fact that even in the context of dementia or other mental of functional impairment, important areas of reserve or strength may be present, such as financial-judgment capacity. The value of standardization is the opportunity to assess a domain across time and practitioners and be confident that the same areas are being assessed. Furthermore, only when an assessment is rooted in a sentinel financial transaction or decision can a third party render an opinion about whether financial exploitation is present or not, since financial decision-making capacity in high-risk older adults is rarely entirely present or entirely absent (Dong, 2014).

Psychological issues, such as psychological vulnerability, and the susceptibility to undue influence also play key roles in financial exploitation. It is important for psychological assessment tools to incorporate both these psychological processes and neurocognitive ones. A new conceptual model to understand and assess financial exploitation and financial decision-making capacity (i.e. the ability to make informed decisions about financial issues) is presented next.

A New Approach to Financial Decision-making Capacity for Specific Sentinel Financial Decisions or Transactions

Framework

A New Model for Understanding Financial Decision Making Capacity and Exploitation

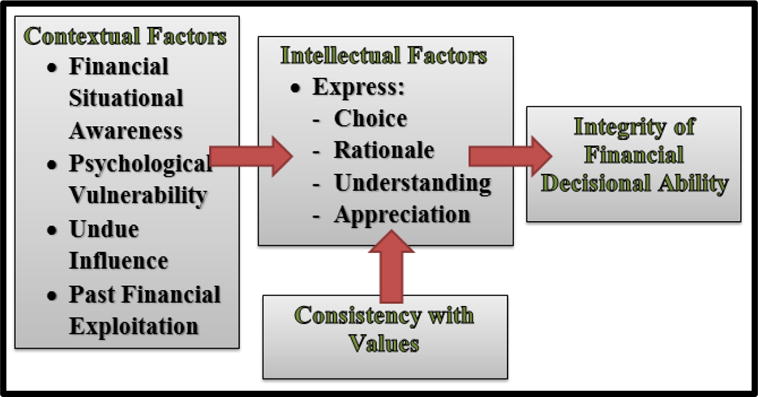

Lichtenberg et al. (2015a) proposed a new model for evaluating financial exploitation and decision making. As can be seen in Figure 1, contextual factors include Financial Situational Awareness (FSA); Psychological Vulnerability (PV), which includes loneliness and depression; Susceptibility to Undue Influence (I); and Risks for Financial Exploitation (FE). Contextual factors, as illustrated by the model, directly influence the core intellectual factors associated with decisional abilities for a sentinel financial transaction or decision.

Figure 1.

Key Components of the Financial Decisional Abilities Model

Financial Situational Awareness refers to an older adult’s (1) Knowledge of the sources of income they utilize; (2) Confidence in their financial decision making abilities and (3) Financial satisfaction and the presence or absence of financial hardships. In assessing financial exploitation that involves financial decision making it is important to know about the experience the older adult has had with money. Lichtenberg et al. (2013) in a study of fraud (a specific form of financial exploitation) found that financial dissatisfaction was related to reports of being defrauded.

Psychological vulnerability refers to conditions such as depression, anxiety, worries about memory loss and problem solving as well as reporting difficulties in getting one’s social needs met. Depression was a predictor of financial exploitation in studies (Beach et al., 2010; Lichtenberg et al., 2013; Lichtenberg et al., 2015b). When depression and a lack of effectiveness in getting social needs met were combined, the experience of fraud was 2–3 times greater in this psychologically vulnerable group versus the rest of the sample. Even when financial skills such as checkbook management and bill payment were the same in a group comparison of financially exploited versus non-exploited older adults, psychological vulnerability still distinguished between the groups.

The Susceptibility to Undue Influence is another key psychological variable to be considered in understanding financial exploitation and decision making of older adults. Shulman, Cohen and Hull (2005) examined 25 cases in which there were challenges to the testamentary capacity of an older adult. Testamentary capacity, examples of which include making a donation or signing a real estate contract (e.g., reverse mortgage) in addition to changing a will, are heavily weighted toward financial decision making skills as opposed to actual management of finances or even performing cash transactions. In 72% of the challenged cases, radical changes were made to the previous will. Fifty-six percent of the cases had documented issues of undue influence. Lichtenberg et al. (2015b) found that susceptibility to undue influence was related to being financially exploited.

Intellectual factors refer to the functional abilities required for financial decision-making capacity and include an older adult’s ability to (1) express a choice (C), (2) communicate the rationale (R) for the choice, (3) demonstrate understanding (U) of the choice, (4) demonstrate appreciation (A) of the relevant factors involved in the choice, and (5) make a choice that is consistent with past values (V). Intellectual factors—unless they are overwhelmed by the impact of contextual factors—are the most proximal and central to determining the integrity of financial decisional abilities. Intellectual factors were drawn from the 25-year tradition of decisional abilities research (Appelbaum and Grisso, 1988) and echoed by more recent work (ABA-APA, 2008; Sherod et al., 2009). The ABA-APA Handbook for Psychologists to assess diminished capacity also highlighted the importance of an older adult’s values.

This model documents the many contextual and psychological influences on informed decision making (intellectual factors) and the preliminary evidence cited above highlights how these contextual variables relate to financial exploitation. This new model lead to the creation of two new scales; the Lichtenberg Financial Decision Making Rating Scale (LFDRS) and the Lichtenberg Financial Decision Screening Scale (LFDSS). The research conducted to date on these scales indicates that they are promising tools for both assessment of financial decision making capacity and financial exploitation.

Preliminary Reliability and Validity of the LFDRS

Psychologists have expertise in assessing whether an older adult is vulnerable, which is a key requirement for the prosecution of perpetrators of financial exploitation. Declining cognitive abilities and mental-health concerns are often evidence that an older adult is vulnerable. In the area of financial capacity, the legal question is, “Did the older adult have the requisite abilities to make the decision in question (e.g., executing a new will)?” Neuropsychological tests can determine the presence or absence of cognitive impairment and dementia and stage it, but cannot directly assess the older adult’s ability to create a will. Below, for instance, are the legal standards for creating a will (i.e., testamentary capacity) in Michigan:

Michigan Code of Law 700.2501 This is a four (4) pronged test:

[The testator] had the ability to understand she was providing for the disposition of her property after her death.

Had the ability to know the nature and extent of her property.

Knew the natural objects of her bounty.

Had the ability to understand in a reasonable manner the general nature and effect of her act in signing a Will.

While most people are aware of steps 1–3 (knowing one’s property, one’s heirs, and one’s plan for distribution) step 4 requires what Appelbaum and Grisso (1988) term “understanding” and “appreciation.” Therefore, choice, understanding, and appreciation are explicitly stated in the legal code for creating a will; the ability to reason is implied, and the legal code specifies that the will cannot be based on delusional thinking. Similar language is used in the legal standards for an individual to execute a contract and even to give a gift.

To date, two studies examined the LFDRS (Lichtenberg et al., 2015a; Lichtenberg et al., 2015b). Inter-rater reliability was examined in the first study and found to be within acceptable limits. Convergent and Construct validity have also been examined. Lichtenberg et al., 2015b in a study of 69 older adults found that decision making abilities and the intellectual factors subscale was positively correlated with both general cognition and financial abilities. The intellectual factors subscale and total decision making abilities rating were also significantly correlated with the recent experience of financial exploitation in the same sample. A rich picture emerged with regard to the LFDRS and its ability to detect financial exploitation, one that allows us to better understand a root cause of this complex problem. Decisional abilities, when impaired, may be one of the greatest risk factors for financial exploitation of older adults. This makes sense conceptually, and is supported by our data. Sixty-three percent of those with impaired decisional ability reported financial exploitation, compared to 13% of the rest of the sample. While the LFDRS is in the early stages of being validated, its conceptual underpinnings, which articulate the specific intersection of financial incapacity and financial exploitation is a new direction in the field.

Preliminary Validity of the LFDSS

While the LFDRS provides psychologists with an assessment tool based on a new conceptual model, the LFDSS is focused on expanding the use of psychological tools beyond the boundaries of psychology. We also created a screening scale based on the items for the intellectual factors and are working with attorneys, financial planners, social workers, adult protective services workers, and others to validate it by having these front-line professionals administer the scale and obtain the ratings themselves. These efforts represent an attempt to bring psychological expertise to the field of financial exploitation. The LFDSS was created purposefully to give financial services professionals (i.e. attorneys, bankers, financial planners, CPAs) a tool to help them spot financial decision making incapacity. The LFDSS was also created to help the criminal justice system, and particularly Adult Protective Services professionals, investigate decision making abilities in cases of suspected financial exploitation. The first empirical study of the LFDSS occurred when a group representing the above mentioned professionals were trained in the administration and scoring of the LFDSS.

One hundred and eight LFDSS cases were included in the first preliminary study. Of the 29 APS cases, 18 (62%) were judged to be substantiated for financial exploitation and 11 to be unsubstantiated. Of the 79 non-APS professional cases, 10 (12%) were judged to have deficits in decision-making capacity and 69 to have full financial decision-making capacity. Taken together, LFDSS risk scores significantly differentiated older adults who were rated as (a) being exploited from those who were not and (b) raising concerns about financial decision-making deficits from those who were not.

Recommendations for Clinical and Applied Work to Detect and Reduce Financial Exploitation

To combat financial exploitation it is recommended that there be an expansion of tools related to financial decision making capacity and financial exploitation. These tools should be used by psychologists as part of an integrative approach. Recent evidence has emerged that elder-abuse teams that include psychologists in the assessment process are the most effective for investigating and subsequently prosecuting financial exploitation (Wood et al., 2014).

A second recommendation is that assessment tools must be created, empirically tested, and widely used by both criminal justice and non-criminal justice professionals. Despite the growing prevalence and adverse impact of elder financial abuse, cases of financial exploitation are difficult to detect and prosecute. Why? Although this problem is undoubtedly multifaceted, an important cause is the distributed nature of case detection. That is, incidences of elder financial exploitation affect multiple professionals across multiple settings, including law enforcement; adult-protective, financial, health, and social services; and the legal system. In response to this problem, in 2003 the Department of Justice initiated a federal program designed to strengthen collaborative responses to family violence. This led to the creation of 80 Family Justice Centers—multidisciplinary alliances that coordinate intervention resources, strengthen community access, and provide education about family violence and elder abuse. Although Family Justice Centers have made a significant impact, they have identified case detection as the biggest impediment to the identification of elder financial abuse.

Most criminal justice professionals who come in contact with financial exploitation have not been formally trained in the assessment of the key variables that underlie financial decision making. In addition, standardized tools that are available to non-psychologist professionals to guide such assessments do not exist. During a recent webinar by the leaders of an Elder Abuse Forensic Center, sponsored by the National Adult Protective Services Association, the lack of easily administered tools to assess financial decision making (capacity) was identified as the chief weakness in the current identification and investigation process (Navarro & Wilber, 2014). Clearly, adult protective services professionals, law-enforcement professionals, and prosecutors would benefit by having assessment tools available to screen for decision making in older adults.

Financial service industry front-line professionals must be trained to assess decision-making abilities when confronted with significant financial transactions being made by older adults. The only way to curb financial exploitation is by making screening assessments of decision-making abilities available to financial services professionals before an older adult makes a large purchase, bank transfer, investment or withdrawal. Professionals and staff in certain contexts must have higher standards of practice that include explicit assessment of decision-making abilities, and these assessment measures must be empirically tested. The list of potential users is broad and includes bankers, financial planners, CPAs, insurance sales personnel, trust officers, geriatric care managers, social and health-service workers, and even employees at places such as Western Union and Walmart, which frequently wire large sums of money for older adults who may be victims of financial exploitation.

Recommendations for Policy

Focusing on elder mistreatment, Pillemer, Connolly, Breckman, Spreng, & Lachs (2015) highlight the importance of more research funding and emphasize that Alzheimer’s disease renders older adults more susceptible to all types of elder abuse. Taking this argument further, based on the research cited at the beginning of this article, even cognitive impairment without dementia often renders older adults more vulnerable to financial exploitation. The implications of these conclusions are impactful; with the growing number of older adults with Alzheimer’s disease continued increases in funding for the 2011 Elder Justice Act as part of the Affordable Care Act (which recognized in federal law older adults’ rights to be free from abuse and exploitation) will enable financial exploitation to receive an ever more increasing focus. The biggest impact of this may well be the increase in multi-disciplinary teams to address the issue. The ever increasing spot light on the problem of financial exploitation in older adults will also move the financial service industry professions to have higher standards with regard to how they detect and assess for cognitive impairment and financial decision making.

References

- American Bar Association Commission on Law and Aging and American Psychological Association [ABA/APA] Assessment of older adults with diminished capacity: A handbook for psychologists. Washington, DC: American Bar Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB, Resnick HS, Steve K, Muzzy W, Kilpatrick DG. Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study. Journal Information. 2010;100(2):292–297. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2011;7(3):270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. New England Journal of Medicine. 1988;319:1635–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812223192504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SR, Schulz R, Castle NG, Rosen J. Financial exploitation and psychological mistreatment among older adults: Differences between African Americans and Non-African Americans in a population-based survey. The Gerontologist. 2010;50(6):744–757. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle G. ‘She’s usually quicker than the calculator’: Financial management and decision-making in couples living with dementia. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2013;21(5):554–562. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA, Yu L, Wilson RS, Gamble K, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Poor decision making is a consequence of cognitive decline among older persons without Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment. PloS One. 2012;7(8):e43647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad KJ, Iris M, Ridings JW, Langley K, Wilber KH. Self-report measure of financial exploitation of older adults. The Gerontologist. 2010;50(6):758–773. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X. Elder abuse: Research, practice, and health policy. The 2012 GSA Maxwell Pollack award lecture. The Gerontologist. 2014;54(2):153–162. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio S. The individual is the core—and key—to person-centered care. Generations. 2013;37(3):16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Flint LA, Sudore RL, Widera E. Assessing financial capacity impairment in older adults. Generations. 2012;36:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the US population: Prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichsen GA. Attitudes about aging. In: Lichtenberg PA, Mast BT, Carpenter BD, Wetherell JL, editors. APA Handbook of clinical geropsychology: History and status of the field and perspectives on aging. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2015. pp. 363–378. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JW, Willis R. Dementia risk and financial decision making by older households: The impact of information. Dementia. 2013;7(4):45. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2339225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SL, Hafemeister TL. APS investigation across four types of elder maltreatment. Journal of Adult Protection. 2012;14(2):82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp BJ, Mosqueda LA. Elder financial abuse: An evaluation framework and supporting evidence. Journal of American Geriatric Society. 2005;53:1123–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Leitsch SA, Waite LJ. Elder mistreatment in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a nationally representative study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2008;63(4):S248–S254. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.4.s248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg PA, Stickney L, Paulson D. Is psychological vulnerability related to the experience of fraud in older adults? Clinical Gerontologist. 2013;36(2):132–146. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2012.749323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg PA, Stoltman J, Ficker LJ, Iris M, Mast BT. A person-centered approach to financial capacity: Preliminary development of a new rating scale. Clinical Gerontologist. 2015a;38:49–67. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2014.970318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg PA, Ficker LJ, Rahman-Filipiak A. Financial Decision-making Abilities and Financial Exploitation in Older African Americans: Preliminary Validity Evidence for the Lichtenberg Financial Decision Rating Scale (LFDRS) Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect. 2015b doi: 10.1080/08946566.2015.1078760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg PA. Misdiagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Cases of capacity. Clinical Gerontologist. 2011;35:42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Marson DC. Loss of financial competency in dementia: Conceptual and empirical approaches. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2001;8:164–181. [Google Scholar]

- Marson DC, Martin RC, Wadley V, Griffith HR, Snyder S, Goode PS, Harrell LE. Clinical interview assessment of financial capacity in older adults with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(5):806–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mast BT. Whole person dementia assessment. Baltimore, MD: Health Professions Press, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Jr, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2011;7(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberg PJ, Kniele K. Evaluation of competency: Ethical considerations for neuropsychologists. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult. 2006;13:101–114. doi: 10.1207/s15324826an1302_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moye J, Marson DC. Assessment of decision-making capacity in older adults: An emerging area of practice and research. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007;62B:P3–P11. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.1.p3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro A, Wilber K. Prosecution of financial exploitation cases: Lessons from an elder abuse forensic center [PDF slides] 2014 Jan; Retrieved from Napsa-Now Online Website: http://www.nccdglobal.org/sites/default/files/content/navarro-wilber.pdf.

- Nerenberg L, Davies M, Navarro AE. In pursuit of a useful framework to champion elder justice. Generations. 2012;36:89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Okonkwo OC, Griffith HR, Vance DE, Marson DC, Ball KK, Wadley VG. Awareness of functional difficulties in mild cognitive impairment: A multidomain assessment approach. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(6):978–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Connolly MT, Breckman R, Spreng N, Lachs MS. Elder mistreatment: Priorities for consideration by the White House Conference on Aging. The Gerontologist. 2015;55(2):320–327. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher G, Heeringa SG, Weir DR, Ofstedal MB, Wallace RB. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148:427–434. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherod MG, Griffith HR, Copeland J, Belue K, Krzywanski S, Zamrini E, Marson DC. Neurocognitive predictors of financial capacity across the dementia spectrum: Normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2009;15:258–67. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709090365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivapour SK, Nguyen CM, Cole CA, Denburg NL. Effects of age, sex, and neuropsychological performance on financial decision-making. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2012;6:82. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2012.00082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman KI, Cohen CA, Hull I. Psychiatric issues in retrospective challenges of testamentary capacity. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;20:63–69. doi: 10.1002/gps.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Phelps CH. Toward defining preclinical aspects of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiegel LA. An overview of elder financial exploitation. Generations. 2012;36(2):73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch CJ. Person-centered care in the early stages of dementia: Honoring individuals and their choices. Generations. 2013;37(3):30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wood S, Rakela B, Liu PJ, Navarro AE, Bernatz S, Wilber KH, Schneider D. Neuropsychological profiles of victims of financial elder exploitation at the Los Angeles County Elder Abuse Forensic Center (LACEAFC) Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect. 2014;26(4):414–423. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2014.881270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]