Abstract

Rationale: The contribution of air pollution to the risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is unknown.

Methods: We studied 1,558 critically ill patients enrolled in a prospective observational study at a tertiary medical center who lived less than 50 km from an air quality monitor and had an ARDS risk factor. Pollutant exposures (ozone, NO2, SO2, particulate matter < 2.5 μm, particulate matter < 10 μm) were assessed by weighted average of daily levels from the closest monitors for the prior 3 years. Associations between pollutant exposure and ARDS risk were evaluated by logistic regression controlling for age, race, sex, smoking, alcohol, insurance status, rural versus urban residence, distance to study hospital, and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II.

Measurements and Main Results: The incidence of ARDS increased with increasing ozone exposure: 28% in the lowest exposure quartile versus 32, 40, and 42% in the second, third, and fourth quartiles (P < 0.001). In a logistic regression model controlling for potential confounders, ozone exposure was associated with risk of ARDS in the entire cohort (odds ratio, 1.58 [95% confidence interval, 1.27–1.96]) and more strongly associated in the subgroup with trauma as their ARDS risk factor (odds ratio, 2.26 [95% confidence interval, 1.46–3.50]). There was a strong interaction between ozone exposure and current smoking status (P = 0.007). NO2 exposure was also associated with ARDS but not independently of ozone exposure. SO2, particulate matter less than 2.5 μm, and particulate matter less than 10 μm were not associated with ARDS.

Conclusions: Long-term ozone exposure is associated with development of ARDS in at-risk critically ill patients, particularly in trauma patients and current smokers. Ozone exposure may represent a previously unrecognized environmental risk factor for ARDS.

Keywords: air pollution, ozone, acute lung injury, pulmonary edema

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Ozone induces lung inflammation and oxidative stress in humans and experimental models. In population-based studies, ozone exposure has been implicated in hospital admissions and mortality related to heart and lung disease. Recent evidence suggests that environmental exposures such as tobacco smoke and alcohol abuse may enhance the risk of developing acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), but the effect of exposure to ambient levels of environmental pollutants such as ozone on risk of ARDS has not been investigated.

What This Study Adds to the Field

We found that long-term ozone exposure, even at relatively low levels, is associated with development of ARDS in at-risk critically ill patients. These findings suggest that ozone exposure, like other environmental exposures such as alcohol and tobacco, may represent an important and previously unrecognized risk factor for development of ARDS.

The acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a common syndrome of acute lung inflammation, noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, and acute respiratory failure (1). With a U.S. incidence of 190,000 cases per year and mortality of 30 to 40% (2), ARDS is an important and costly public health problem. The most common clinical risk factors for ARDS are sepsis, pneumonia, severe trauma, aspiration of gastric contents, and multiple transfusions (3). However, ARDS develops in only a subset of patients with these risk factors. The mechanisms that predispose to ARDS in some, but not all, at-risk patients are not understood.

Recent evidence suggests that environmental exposures such as tobacco smoke (4–6) and alcohol abuse (7) may enhance the risk of developing ARDS, but the effect of exposure to ambient levels of environmental pollutants on risk of ARDS has not been investigated. We hypothesized that long-term exposure to high levels of ambient pollutants primes the lung to develop ARDS in the setting of another clinical risk factor. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the association between ARDS and long-term exposure to air pollutants including ozone, NO2, particulate matter less than 2.5 μm [PM2.5], particulate matter less than 10 μm [PM10], and SO2 in a large cohort of critically ill patients at risk for ARDS.

Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (8).

Methods

A complete description of methods is available in the online supplement.

Patients

We studied patients from VALID (Validating Acute Lung Injury Biomarkers for Diagnosis), a prospective observational cohort of critically ill medical, surgical, and trauma patients admitted to Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) (9–12). Subjects enrolled from 2006 to 2012 were included if a residential address was available, they lived within 50 km of at least one U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-approved air quality monitor, and they had an ARDS risk factor.

Clinical Data

Clinical data included demographics, insurance status, current smoking, alcohol use, medical history, medications, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II (13), hemodynamics, ventilator settings, laboratory values, and outcomes. Patients were coded as metro or nonmetro dwellers using U.S. Department of Agriculture 2003 and 2013 Rural–Urban Continuum Codes. Patients were phenotyped at enrollment and on subsequent 3 days for sepsis (14), organ dysfunction (15), and ARDS. Patients were classified as having ARDS if they met American European Consensus Conference (16) criteria for acute lung injury (ALI) or ARDS on two or more consecutive days and as having no ARDS if they did not meet criteria on any day. Patients meeting criteria on a single or on two nonconsecutive days were deemed “indeterminate” ARDS status and were included only in a sensitivity analysis.

Air Pollutant Exposure Estimates

Daily measurements of ozone, NO2, SO2, PM2.5, and PM10 were obtained from the EPA’s Aerometric Information Retrieval System. The 24-hour average was computed for each pollutant except for ozone. Because ozone levels are typically elevated only during daylight hours, the highest 8-hour average was used. Because ozone levels are monitored only in warmer months in Tennessee, ozone data were restricted to April through September.

Patient addresses were geocoded and distances to all monitors calculated (Haversine formula). Daily pollutant exposures were estimated by the inverse-distance-squared weighted average of daily levels from monitors within 50 km (17). Long-term exposures were estimated using average pollutant levels for the 1-, 3-, and 5-year periods before ICU admission and short-term exposures using levels for the prior 3 days and 6 weeks. Findings for 1-, 3-, and 5-year ozone exposures were similar; 3-year data are presented. Because no significant associations between long-term exposures to SO2, PM2.5, and PM10 and risk of ARDS were observed, these are presented in the online supplement. As there were no associations between any short-term air pollutant exposure and ARDS, these data are not shown. For reference, correlations between pollutant levels are shown in Table E1 in the online supplement.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical data were compared between patients with and without ARDS using Pearson chi-square tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Missing values of regression covariates were multiply imputed with predictive mean matching (18) to avoid case-wise deletion of patient records. We fit logistic regression models to examine the relationship between ARDS and pollutant levels controlling for prespecified confounders including age, race, sex, enrollment month (to control for season), current smoking, alcohol use, insurance status (as a proxy for socioeconomic status), median household income, metro versus nonmetro residence, distance to VUMC, APACHE II, injury severity score (trauma subset only), and blunt versus penetrating trauma. A restricted cubic spline with three knots was used for age, month, and APACHE II to permit nonlinear associations. Data analyses were performed using R Version 3 (R Core Team).

Results

Patients

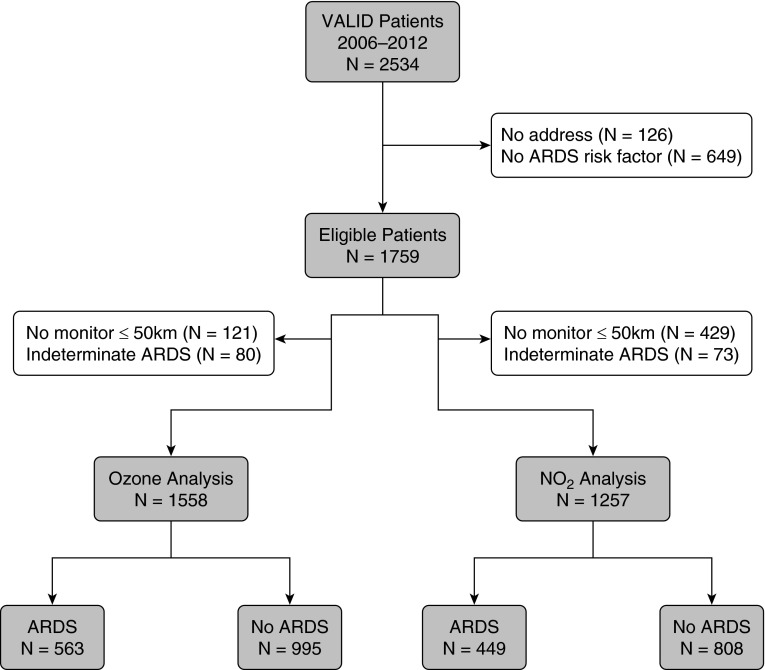

Differences between patients who were eligible for inclusion in the study and those who were not eligible related to the requirement for living within 50 km of an air pollution monitor, leading to more nonmetro dwellers and a farther distance to Vanderbilt among excluded patients (Table E2). There were 1,558 patients who met the inclusion criteria for the ozone analysis and 1,257 who met the inclusion criteria for the NO2 analysis (Figure 1). There were 1,350, 1,355, and 1,130 patients available for the SO2, PM2.5, and PM10 analyses, respectively; levels of the individual air pollutants were only moderately correlated (Table E1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram summarizing patient selection for the ozone and NO2 analyses. ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; VALID = Validating Acute Lung Injury Biomarkers for Diagnosis.

Patient characteristics for the ozone analysis are in Table E3. Of the 1,558 patients, 563 met criteria for ARDS. Patients with ARDS were older, were more likely to have sepsis as their ARDS risk factor, and had a higher severity of illness than patients who did not develop ARDS.

Ozone Exposure and ARDS

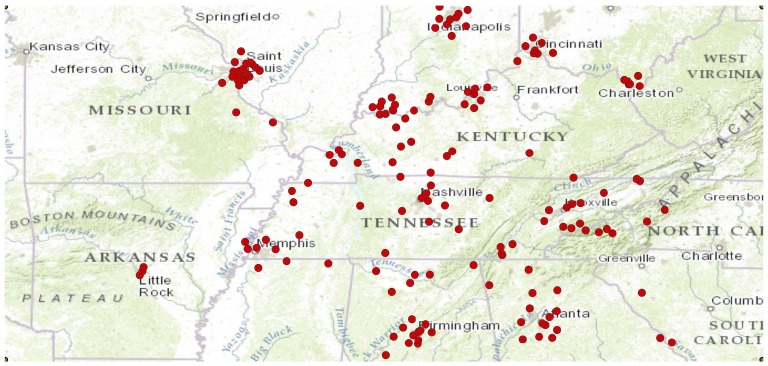

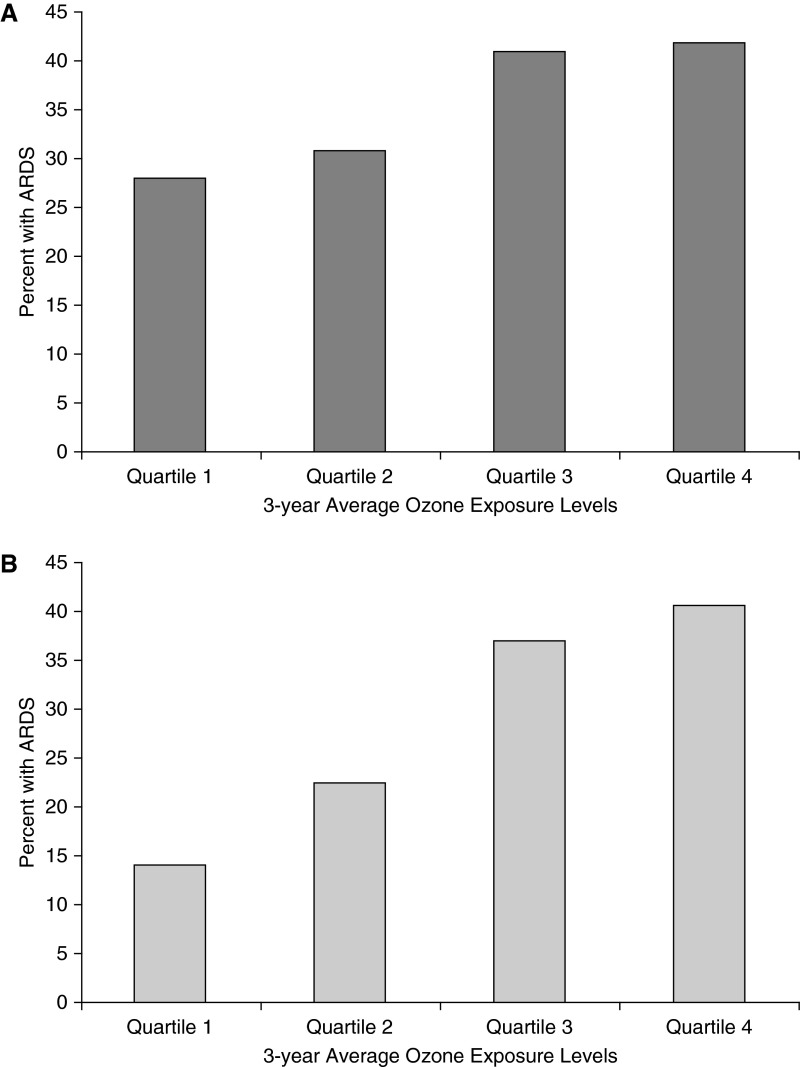

The geographic distribution of the ozone monitors that were included in the study is shown in Figure 2. The median distance from a patient’s residence to the nearest air quality monitor was 19 km. Three-year average ozone exposure levels were lower than current EPA standards (19) (median, 51.5 ppb; range, 41.5–58.2). Despite these low levels of exposure, the incidence of ARDS increased significantly with increasing long-term ozone exposure (Table 1, Figure 3A). In a logistic regression model that controlled for potential confounders, long-term ozone exposure was independently associated with risk of ARDS (Table 2, Figure 4A). The findings were not different if 24-hour average levels of ozone were used rather than the highest daily 8-hour average (Table E4).

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of the 163 ozone monitors that contributed exposure data for the ozone analysis.

Table 1.

Comparison of Patients by Quartile of Ozone Exposure

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ozone, 3-yr average, ppb* | 41.5–49.0 | 49.0–51.5 | 51.5–53.5 | 53.5–58.2 | |

| Age, yr | 53 (40–64) | 54 (37–65) | 52 (36–62) | 52 (40–63) | 0.64 |

| Male | 214 (60) | 214 (61) | 202 (57) | 219 (62) | 0.56 |

| White | 239 (67) | 289 (82) | 319 (90) | 314 (89) | <0.001 |

| Current smoker | 138 (42) | 119 (38) | 132 (41) | 139 (41) | 0.74 |

| Alcohol abuse | 74 (21) | 60 (17) | 67 (19) | 64 (18) | 0.62 |

| Insurance, group 1† | 205 (58) | 243 (69) | 250 (71) | 231 (66) | 0.001 |

| APACHE II | 25 (20–30) | 25 (20–31) | 25 (20–31) | 26 (21–31) | 0.34 |

| Distance to VUMC, km | 11 (6–51) | 49 (17–100) | 70 (31–102) | 73 (52–120) | <0.001 |

| Metro (vs. nonmetro) residence county | 293 (82) | 249 (70) | 260 (73) | 222 (63) | <0.001 |

| ARDS risk factor | |||||

| Trauma | 116 (33) | 140 (40) | 144 (40) | 143 (40) | 0.19 |

| Sepsis | 194 (54) | 182 (51) | 177 (50) | 178 (50) | |

| Other | 47 (13) | 32 (9) | 35 (10) | 33 (9) | |

| Zip code–based household income, $1,000 | 39.2 (30.4–47.8) | 44.8 (38.2–57.0) | 45.2 (38.1–56.0) | 43.0 (36.8–51.5) | <0.001 |

| ARDS | 100 (28) | 109 (31) | 146 (41) | 148 (42) | <0.001 |

Definition of abbreviations: APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; IQR = interquartile range; VUMC = Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Data presented as n (%) or median (IQR) unless otherwise noted.

Data are reported as ppb range for each quartile.

Group 1 = private, Medicare, federal.

Figure 3.

Relationship between quartile of ozone exposure and development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). In an unadjusted analysis of all patients (A) and the subset with trauma as their ARDS risk factor (B), patients in the second, third, and fourth quartiles of 3-year ozone exposure estimates were significantly more likely to develop ARDS (P < 0.001 by Pearson test for both A and B). (A) The incidence of ARDS was 28.0%, (95% confidence interval [CI], 23.4–32.7%) in quartile 1, 30.8% (95% CI, 26.0–35.6%) in quartile 2, 41.0% (95% CI, 36.0–46.1%) in quartile 3, and 41.8% (95% CI, 36.7–46.9%) in quartile 4. (B) The incidence of ARDS was 13.8% (95% CI, 7.5–20.1%) in quartile 1, 22.9% (95% CI, 15.9–29.8%) in quartile 2, 38.9% (95% CI, 30.9–46.9%) in quartile 3, and 41.3% (95% CI, 33.2–49.3%) in quartile 4.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Analysis for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Ozone Cohort

| Variable | Comparator | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ozone | 5-ppb increment (49–54) | 1.58 | 1.27–1.96 |

| Age | Q3:Q1* | 0.95 | 0.79–1.14 |

| Sex | Female:male | 1.05 | 0.84–1.31 |

| Race | Nonwhite:white | 0.70 | 0.50–0.98 |

| Current smoker | Smoker:nonsmoker | 0.98 | 0.75–1.28 |

| Alcohol abuse | Yes:no | 0.94 | 0.70–1.28 |

| Insurance status | Group 2:group 1† | 0.93 | 0.71–1.22 |

| APACHE II | Q3:Q1‡ | 1.83 | 1.55–2.16 |

| Distance to VUMC | Q3:Q1§ | 0.89 | 0.62–1.28 |

| Residence county | Nonmetro:metro | 0.92 | 0.67–1.26 |

| Enrollment month | September:March | 0.92 | 0.75–1.12 |

| Median household income | Q3:Q1|| | 0.88 | 0.72–1.08 |

Definition of abbreviations: APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; Q = quartile; VUMC = Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Lower quartile is 39 and upper quartile is 64.

Group 1 = private, Medicare, federal; Group 2 = TennCare, Medicaid, none.

Lower quartile is 20 and upper quartile is 31.

Lower quartile is 19 and upper quartile is 109.

Lower quartile is $35,800 and upper quartile is $51,500.

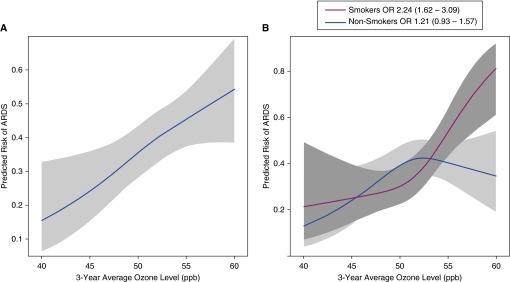

Figure 4.

Relationship between 3-year average ozone exposure level and predicted risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in a logistic regression model controlling for age, race, sex, enrollment month, smoking, alcohol use, insurance status, zip code–based median household income, metro versus nonmetro residence, distance to the Vanderbilt University Medical Center, and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II in (A) all patients in the ozone analysis, and (B) the same patients segregated by smoking status. The association between 3-year average ozone exposure level and predicted risk of ARDS differed between smokers and nonsmokers and was only significant in the smokers. OR = odds ratio.

The association between ARDS and ozone exposure was strongest in the subgroup of patients (n = 552) with trauma as their ARDS risk factor (Figure 3B). In a logistic regression model that controlled for potential confounders, long-term ozone exposure was independently associated with risk of ARDS in trauma patients (Table E5). The interaction between trauma and ozone exposure was statistically significant (P = 0.039).

NO2 exposure and ARDS

Patient characteristics for the NO2 analysis are in Table E6. NO2 exposure levels were relatively low (median, 15.4 ppb; range, 1.7–17.7). Although overall rates of ARDS across quartiles of NO2 exposure were not significantly different in an unadjusted analysis (Table E7), NO2 exposure was associated with risk of ARDS in a logistic regression model that controlled for potential confounders (Table E8). As with ozone, the effect was strongest in trauma patients (n = 419; odds ratio [OR] per 5-ppb increase, 1.92; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.25–2.94). When 3-year ozone and NO2 exposure were included in the same model, only ozone exposure remained significantly associated with ARDS (Table E9).

Interaction with Smoking and Alcohol

Because exposure of the lung to cigarette smoke could be synergistic with ozone for increasing the risk of ARDS, we tested for an interaction between current smoking and ozone exposure. The interaction term was highly significant (P = 0.007). Ozone was significantly associated with ARDS only in current smokers and not in nonsmokers (Figure 4B). There was no association between alcohol and ARDS in this study and no interaction between alcohol and ozone (P value for interaction, 0.60) or any other pollutant.

Sensitivity Analyses

To determine if accuracy of exposure estimates affected the findings, we restricted analysis to patients living within 15 km of a monitor. None of the analyses were substantively changed (not shown). In a second sensitivity analysis, we included the 80 patients with “indeterminate” ARDS status as control subjects. Ozone exposure was still associated with ARDS (OR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.25–1.94), especially in trauma patients (OR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.46–3.51). The interaction of ozone exposure with smoking was unchanged (P < 0.001).

Discussion

In critically ill patients at risk for ARDS, long-term exposure estimates for ozone based on residential address were associated with development of ARDS. Importantly, this association was independent of other known risk factors for ARDS, such as age and severity of illness. In addition, this association persisted after adjustment for potential confounders, including metro versus nonmetro dwelling, source of insurance and median household income as indicators of socioeconomic status, and distance of residence from the study hospital, which was included to control for possible unmeasured differences in severity of illness that could lead to transfer to VUMC of sicker patients from remote hospitals with different levels of pollutant exposure. We also found an association of long-term exposure to NO2 and risk of ARDS; however, in two pollutant models with ozone and NO2, only ozone remained significant. There was no association between exposure estimates for other pollutants (SO2, PM2.5, and PM10) and ARDS. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an association between ambient air pollution and risk of ARDS. Furthermore, the observed association occurred at relatively low levels of exposure that fall within current EPA standards, suggesting that these observations, if reproduced, could be relevant even in areas with low levels of ambient ozone. Based on these findings, long-term exposure to ozone could represent a previously unrecognized risk factor for development of ARDS.

Although ozone exposure has not previously been associated with ARDS, both acute and chronic ozone exposure have been associated with respiratory disease in experimental and clinical studies. Acute ozone exposure induces acute lung injury in animals, primarily by producing an oxidant-mediated injury to the lung epithelium that leads to increased permeability and lung inflammation (20). Controlled short-term exposure to ozone (at doses that are much higher than ambient pollutant levels) in humans also causes airway inflammation and oxidant injury (21–23). In epidemiologic studies, acute exposure to high ozone levels has been associated with asthma exacerbations (24). Both ozone and NO2 exposure over the preceding 6 weeks were associated with acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (25), a syndrome that shares pathologic features with ARDS. Chronic ozone exposure has been associated with decreased lung growth in children (26, 27) and decreased small airway function in young adults (28). In a study of more than 400,000 subjects, chronic ozone exposure was associated with mortality from respiratory causes (29); data on ARDS as a cause of respiratory mortality were not available in that study.

In the current study, the association between ARDS and ozone exposure was strongest in patients at risk for ARDS from severe trauma. Because it is well established that trauma-associated ARDS is clinically and pathophysiologically different from ARDS due to other causes (30), ambient ozone exposure may uniquely prime the lung to develop ARDS in the setting of severe trauma. The higher rate of smoking in the trauma group (54%) compared with the nontrauma group (34%, P < 0.0001) may have potentiated the effects of ambient ozone exposure. Because the incidence of ARDS in the trauma group was lower (32%) than in the nontrauma patients (40%), another potential explanation is that other ARDS risk factors, such as sepsis, represent such a potent and overwhelming stimulus for ALI that the contribution of chronic ozone exposure to risk of ARDS is less apparent. Finally, it is possible that patients who develop ARDS as a result of trauma spend more time outdoors than patients with other ARDS risk factors, leading to higher exposure levels to ambient pollutants.

Smoking has only recently been recognized to be an independent risk factor for ARDS. Prospective studies report a strong association between cigarette smoking and risk of ARDS in severe trauma (4), nonpulmonary sepsis (6), lung transplant recipients (31), and patients receiving blood transfusions (5). Indeed, given the low levels of ambient ozone exposure in the VALID cohort, it is somewhat surprising that the effect of smoking on development of ARDS does not overwhelm the signal from ozone exposure. Potential mechanisms for potentiation of ARDS by smoking have considerable overlap with mechanisms of ozone-induced lung injury (32). These include harmful effects on lung epithelial and endothelial permeability and function (33, 34), proinflammatory effects due to changes in neutrophil alveolar macrophage trafficking and function, and effects on cell-mediated and humoral immunity (35, 36). Smoking and air pollutant exposure have previously been shown to have synergistic effects on risk of obesity, pulmonary function deficits, and lung cancer (37–39). The strong interaction between smoking and ozone exposure in the current study suggests that ozone exposure may also potentiate the harmful effects of tobacco smoke on the lung regarding ARDS risk. This observation is important, because both smoking and air pollution exposure are potentially modifiable environmental risk factors for developing ARDS.

Although we found an association between long-term NO2 exposure and ARDS, this association was not significant after controlling for ozone levels. There are several potential explanations. First, because nitrogen oxides are the most prevalent ambient reactant for ozone formation, the association between NO2 and risk of ARDS may only be indicative of ozone exposure. Second, because nitrogen oxides are predominantly traffic-related pollutants, exposure estimates based on regional monitors may not be accurate. Studies that analyze distance to roadway might be better suited to determine the relationship between NO2 or other traffic-related pollutants such as PM2.5 and PM10 and development of ARDS. Finally, because there were fewer monitoring stations for NO2 than for ozone, this analysis had less power.

This study has several strengths. First, we studied a large heterogeneous cohort of critically ill medical, surgical, and trauma patients, enhancing the potential generalizability of the findings. Second, the patients were rigorously phenotyped prospectively for both ARDS risk factors and development of ARDS by physician investigators. This is in sharp contrast to many epidemiologic studies that have relied on inherently less reliable death certificate data or administrative coding for patient phenotyping. Third, residential addresses and dates of admissions were used for exposure estimates, allowing for individualized rather than population- or neighborhood-based exposure estimates. Finally, the extensive prospective data collection in the VALID study allowed us to control for a large number of potential confounders, decreasing but not eliminating the possibility of residual confounding.

This study has some limitations. First, patients were drawn from only one geographic region, and air pollutant effects may differ by geographic region. Second, as in any study that does not directly measure air pollutant levels, there is the possibility of exposure misclassification. To mitigate the concern of exposure misclassification, a sensitivity analysis included only patients who lived within 15 km of a monitor with similar results. Exposure misclassification could also be caused by reliance on the address provided at hospital admission; information about prior addresses during the exposure period was not available. Exposure misclassification may also arise from exposures that occur away from the residence, including at the place of occupation. Number of hours spent outdoors versus indoors could also affect total exposure and would not be captured in our estimates. Third, the possibility of residual confounding and in particular residual spatial confounding remains. We attempted to mitigate this concern by including socioeconomic status (measured by insurance source and zip code–based median household income), metro versus nonmetro residence, and distance to the study hospital in the regression models. However, given the concern for potential unmeasured confounders, it will be important to confirm these findings in geographically diverse patient groups with both higher and lower levels of ozone exposure. Fourth, in this exploratory study, we did not aim to strictly control the type I error rate. To minimize the likelihood of identifying false-positive associations, we prespecified the variables and interaction terms to include in the primary models before data examination. Subgroup analyses such as trauma/nontrauma were also prespecified. Although we did not adjust for multiple comparisons, our primary finding of ozone–ARDS association has a P value of less than 0.001, which would be significant with post hoc significance adjustment using a conservative Bonferroni method. Finally, because this was an observational study, causality cannot be inferred.

In summary, in a large group of rigorously phenotyped critically ill patients, we report an association between long-term ozone exposure levels and risk of developing ARDS. This risk was potentiated by cigarette smoking and was strongest in patients with severe trauma as their ARDS risk factor. These findings indicate that ozone exposure may be a previously unrecognized environmental risk factor for ARDS.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants P30 ES000267 (L.B.W.), HL110969 (C.S.C.), and HL51856 (M.A.M.).

Author Contributions: All authors made substantial contributions to the design of the study and data acquisition and interpretation. Z.Z. and T.K. were primarily responsible for the data analysis. L.B.W. drafted the manuscript, and all authors critically revised it. All authors provided final approval for the version submitted for publication and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1418OC on December 17, 2015

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman GA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2731–2740. doi: 10.1172/JCI60331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, Weaver J, Martin DP, Neff M, Stern EJ, Hudson LD. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1685–1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calfee CS, Matthay MA, Eisner MD, Benowitz N, Call M, Pittet JF, Cohen MJ. Active and passive cigarette smoking and acute lung injury after severe blunt trauma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1660–1665. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1802OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toy P, Gajic O, Bacchetti P, Looney MR, Gropper MA, Hubmayr R, Lowell CA, Norris PJ, Murphy EL, Weiskopf RB, et al. TRALI Study Group. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: incidence and risk factors. Blood. 2012;119:1757–1767. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-370932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calfee CS, Matthay MA, Kangelaris KN, Siew ED, Janz DR, Bernard GR, May AK, Jacob P, Havel C, Benowitz NL, et al. Cigarette smoke exposure and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1790–1797. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moss M, Parsons PE, Steinberg KP, Hudson LD, Guidot DM, Burnham EL, Eaton S, Cotsonis GA. Chronic alcohol abuse is associated with an increased incidence of acute respiratory distress syndrome and severity of multiple organ dysfunction in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:869–877. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000055389.64497.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ware LB, Zhao Z, Koyama T, Matthay MA, Lurmann F, Balmes JR, Calfee CS. Long-term ozone exposure levels are associated with development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:A2174. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1418OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siew ED, Ikizler TA, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A, Wickersham N, Bossert F, Peterson JF, Parikh CR, May AK, Ware LB. Elevated urinary IL-18 levels at the time of ICU admission predict adverse clinical outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1497–1505. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09061209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siew ED, Ware LB, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A, Moons KG, Wickersham N, Bossert F, Ikizler TA. Urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin moderately predicts acute kidney injury in critically ill adults. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1823–1832. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware LB, Fessel JP, May AK, Roberts LJ., II Plasma biomarkers of oxidant stress and development of organ failure in severe sepsis. Shock. 2011;36:12–17. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318217025a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Neal HR, Jr, Koyama T, Koehler EA, Siew E, Curtis BR, Fremont RD, May AK, Bernard GR, Ware LB. Prehospital statin and aspirin use and the prevalence of severe sepsis and acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1343–1350. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182120992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM, Sibbald WJ The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Chest. 1992;101:1644–1655. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernard G. The Brussels score. Sepsis. 1997;1:43–44. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, Legall JR, Morris A, Spragg R the Consensus Committee. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS: definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pope CA, III, Ezzati M, Dockery DW. Fine-particulate air pollution and life expectancy in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:376–386. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0805646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Little RJA, Rubin DB. New York: Wiley; 1987. Statistical analysis with missing data. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rice MB, Guidotti TL, Cromar KR ATS Environmental Health Policy Committee. Scientific evidence supports stronger limits on ozone. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:501–503. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201411-1976ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mustafa MG. Biochemical basis of ozone toxicity. Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;9:245–265. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90035-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen C, Arjomandi M, Balmes J, Tager I, Holland N. Effects of chronic and acute ozone exposure on lipid peroxidation and antioxidant capacity in healthy young adults. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:1732–1737. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aris RM, Christian D, Hearne PQ, Kerr K, Finkbeiner WE, Balmes JR. Ozone-induced airway inflammation in human subjects as determined by airway lavage and biopsy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:1363–1372. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.5.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mudway IS, Kelly FJ. An investigation of inhaled ozone dose and the magnitude of airway inflammation in healthy adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:1089–1095. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200309-1325PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guarnieri M, Balmes JR. Outdoor air pollution and asthma. Lancet. 2014;383:1581–1592. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60617-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johannson KA, Vittinghoff E, Lee K, Balmes JR, Ji W, Kaplan GG, Kim DS, Collard HR. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis associated with air pollution exposure. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:1124–1131. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00122213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang BF, Chen YH, Lin YT, Wu XT, Leo Lee Y. Relationship between exposure to fine particulates and ozone and reduced lung function in children. Environ Res. 2015;137:382–390. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen CH, Chan CC, Chen BY, Cheng TJ, Leon Guo Y. Effects of particulate air pollution and ozone on lung function in non-asthmatic children. Environ Res. 2015;137:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tager IB, Balmes J, Lurmann F, Ngo L, Alcorn S, Künzli N. Chronic exposure to ambient ozone and lung function in young adults. Epidemiology. 2005;16:751–759. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000183166.68809.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Pope CA, III, Ito K, Thurston G, Krewski D, Shi Y, Calle E, Thun M. Long-term ozone exposure and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1085–1095. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calfee CS, Eisner MD, Ware LB, Thompson BT, Parsons PE, Wheeler AP, Korpak A, Matthay MA Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Trauma-associated lung injury differs clinically and biologically from acute lung injury due to other clinical disorders. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2243–2250. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000280434.33451.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diamond JM, Lee JC, Kawut SM, Shah RJ, Localio AR, Bellamy SL, Lederer DJ, Cantu E, Kohl BA, Lama VN, et al. Lung Transplant Outcomes Group. Clinical risk factors for primary graft dysfunction after lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:527–534. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201210-1865OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moazed F, Calfee CS. Environmental risk factors for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Clin Chest Med. 2014;35:625–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu Q, Sakhatskyy P, Grinnell K, Newton J, Ortiz M, Wang Y, Sanchez-Esteban J, Harrington EO, Rounds S. Cigarette smoke causes lung vascular barrier dysfunction via oxidative stress-mediated inhibition of RhoA and focal adhesion kinase. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L847–L857. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00178.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li XY, Rahman I, Donaldson K, MacNee W. Mechanisms of cigarette smoke induced increased airspace permeability. Thorax. 1996;51:465–471. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.5.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacNee W, Wiggs B, Belzberg AS, Hogg JC. The effect of cigarette smoking on neutrophil kinetics in human lungs. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:924–928. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198910053211402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arcavi L, Benowitz NL. Cigarette smoking and infection. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2206–2216. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.20.2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner MC, Cohen A, Jerrett M, Gapstur SM, Diver WR, Pope CA, III, Krewski D, Beckerman BS, Samet JM. Interactions between cigarette smoking and fine particulate matter in the Risk of Lung Cancer Mortality in Cancer Prevention Study II. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180:1145–1149. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McConnell R, Shen E, Gilliland FD, Jerrett M, Wolch J, Chang CC, Lurmann F, Berhane K. A longitudinal cohort study of body mass index and childhood exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke and air pollution: the Southern California Children’s Health Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:360–366. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishinakagawa T, Senjyu H, Tanaka T, Asai M, Kotaki K, Yano Y, Miyamoto N, Yanagita Y, Kozu R, Tabusadani M, et al. Smoking aggravates the impaired pulmonary function of officially acknowledged female victims of air pollution of 40 years ago. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2014;234:151–160. doi: 10.1620/tjem.234.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]