Abstract

Background

Immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) are highly effective in preventing unintended pregnancy. State health departments are in the process of implementing a systems change approach to better apply policies supporting the use of immediate postpartum LARC.

Methods

Beginning in 2014, a group of national organizations, federal agencies, and six states have convened a LARC Learning Community to share strategies and best practices in immediate postpartum LARC policy development and implementation. Community activities consist of in-person meetings and a webinar series as forums to discuss systems change.

Results

The Learning Community identified eight domains for discussion and development of resources: training, pay streams, stocking and supply, consent, outreach, stakeholder partnerships, service location, and data and surveillance. The community is currently developing resource materials and guidance for use by other state health departments.

Conclusions

To effectively implement policies on immediate postpartum LARC, states must engage a number of stakeholders in the process, raise awareness of the challenges to implementation, and communicate strategies across agencies during policy development.

Introduction

Immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraceptives (immediate postpartum LARCs) include contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices and are recommended by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) as an effective method to reduce the rate of unintended pregnancy in the United States.1 ACOG released a 2009 Committee Opinion recommending the use of immediate postpartum LARC to reduce repeat adolescent pregnancy and repeat elective abortion among women of reproductive age.1 The United States Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, adapted from the World Health Organization and published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), indicates minimal contraindication for use of LARC during the immediate postpartum period.2 Numerous systematic reviews and research studies have now established immediate postpartum LARC as safe and effective methods for decreasing unintended pregnancy, and use has increased over the last decade.3–10

From 2011 to 2013, the most recent time period for which data have been released, 7% of women aged 15 to 44 years reported using LARC.3 By comparison, use of the oral contraceptive pill (16%), female sterilization (16%), and condoms (9%) were higher than use of LARC.11 Insertion during the immediate postpartum period is ideal, as opposed to the postpartum check-up typically occurring 6 weeks post-delivery, since many women resume sexual activity by this time and ovulation has occurred.12 In fact, research indicates that between 60% and 89% of women attend a scheduled postpartum visit, identifying a missed opportunity for obtaining contraception for a large percentage of women postpartum.13–18 Additionally, recent evidence suggests that immediate postpartum LARC is cost effective, saving approximately $280,000 per insertion in costs associated with an unintended pregnancy per 1,000 women over 2 years.19 Since LARC is a cost-saving, highly effective method for decreasing the risk of unintended pregnancy, and the usage rates are lower than less effective methods, ensuring access to LARC, particularly in the immediate postpartum period is a priority.

Based on current research and clinical practice recommendations, an increasing number of state health departments have explored developing policies for immediate postpartum LARC.20,21 To support states on this emerging issue, the CDC Division of Reproductive Health (CDC/DRH) and the Association for State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) convened the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Office of Population Affairs (OPA), the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), and a group of states in a learning community to better understand the successes and challenges of immediate postpartum LARC policy implementation.22 Six states volunteered to participate in the learning community: Colorado, Georgia, Iowa, Massachusetts, New Mexico, and South Carolina. The purpose of this article is to describe the immediate postpartum LARC Learning Community information-sharing collaborative on state-identified issues surrounding policy implementation as a methodology for affecting systems change. This article summarizes the experiences of these states in the Learning Community, discusses the concept of shared learning as a mechanism for systems change, and provides the foundation for other states to initiate or supplement implementation of immediate postpartum LARC policies.

Building the evidence-base for systems change through prevention strategies

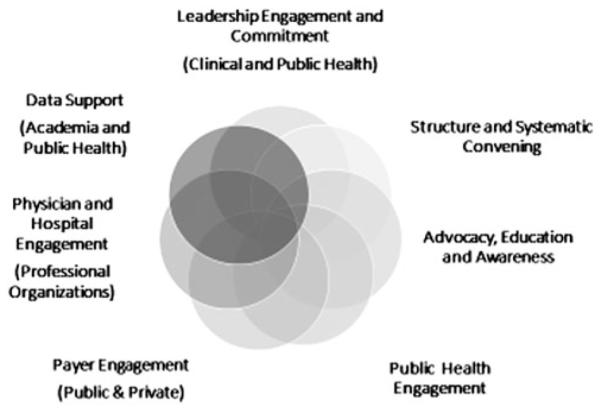

Public health is often faced with complex issues that require integrated systems change in order to drive health improvement. Likewise, to fully address the ten essential services of public health,23 state health departments rely on strategies that maximize use of limited resources to effect sustainable, systemic change. Using national-level collaboratives and communities to facilitate group learning is an effective strategy for both information sharing and developing practical resources for participating states and partners to use when implementing a systems change approach (Fig. 1). Johnson et al. (2004) identify a framework for building capacity to support states in sustaining a prevention strategy.24 The framework is composed of essential factors including (1) developing formal linkages in the administrative structure that maintains the strategy; (2) identifying champions that will lead the strategy; (3) garnering resources to support the strategy; (4) developing administrative policies and procedures to organize the strategy; and (5) ensuring sufficient expertise among staff to integrate the strategy into existing operations. The learning community has adopted this frame-work and applied it to eight identified domains for implementing immediate postpartum LARC policies to support sustainability efforts. Additionally, learning community organizers have developed new strategic partnerships to address some of the resource needs identified by participants. Key to the learning community is the commitment of state health department leadership to raise awareness on this specific public health topic.

FIG. 1.

Components of the systems approach: Types of engagement and support required. Each circle is defined by its adjacent label. The figure moves in a clockwise fashion; darker shading indicates a step further in the systems approach process.

State health officials, the chief health representatives in most states, are uniquely able to facilitate, lead, and catalyze health systems changes. Often, state health officials, with the support of a leadership team, are able to convene key governmental and nongovernmental partners in meetings to target components of the health system requiring direct intervention to effect systems changes. By providing structure and serving as neutral conveners, state health officials facilitate the development of a shared vision and strategic framework for collective action. This allows state and local partners to stay focused on action-oriented work to achieve the shared goal. State health officials are able to effectively engage clinical and community partners to serve as advocates, educators, and champions for evidence-based program and policy change. Hospitals, professional organizations, and academic partners are major influencers in the systems change approach, serving a critical role in operationalizing program and policy changes. Using linked data and epidemiological tools, state health officials, in collaboration with partners, are able to describe health issues in a manner that raises visibility among a broader community of policy-makers and, potentially, funders. Additionally, state health officials are able to leverage the same data to collaborate with public and private payers to drive payment policy reforms. State health officials also leverage the public health workforce to provide services based on the program and policy changes, and support the broader health care system in communities. Effectively developing policies on immediate postpartum LARC occurs when these key elements of systems change take place. State health officials—particularly those collaborating with Medicaid agency counterparts and others in leadership positions—propel this important systems change work.

Description of the immediate postpartum LARC Learning Community

ASTHO uses a standard model for implementing learning communities with states to address high priority issues that require coordination across health departments, state governments, and nongovernmental partners. Participants form state teams with representatives from collaborating intrastate entities and develop consensus-driven plans to address the issue. The model is derived from early work in education by Scardamalia and Bertmeiler (1994) and is defined as a group of individuals with the goal of advancing collective knowledge through collective understanding of a specific issue.25 ASTHO uses these basic concepts when bringing states together in a team environment to share information and resources. ASTHO uses a standard six-stage process for implementing a learning community. This process is described below in the context of the immediate postpartum LARC Learning Community:

1) State participant recruitment – key health department staff from each of the six states are contacted to develop state teams of knowledgeable experts;

2) Baseline key informant interviews – state team members are interviewed to develop a baseline measurement of immediate postpartum LARC understanding and current activities;

3) In-person kick-off meeting – state teams and federal experts are brought together for information-sharing purposes and to identify areas for further technical assistance;

4) Virtual learning events – state teams and federal experts meet via webinar once per month to discuss identified issues and provide technical assistance;

5) Closing meeting – state teams and federal experts meet to share a summary of information generated through-out all events; and

6) Resource guidance – all immediate postpartum LARC Community members participate in development of a foundational immediate postpartum LARC policy and resource guidance to share with other states initiating similar activities.

The immediate postpartum LARC Learning Community is a collective of national experts and organizations, and state health department staff, leadership, clinicians, and advocates. For a comprehensive list of immediate postpartum LARC Learning Community state member professional roles, see Table 1. State teams provide the expert knowledge on immediate postpartum LARC policy implementation, while ASTHO facilitates the learning community, and federal experts provide perspective, knowledge, resources, and other scientific information from the respective agencies.

Table 1.

Professional Role Types of State Participants in the Immediate Postpartum Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives Learning Community

| LARC Learning Community participating states |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Team member professional rolea | Colorado | Georgia | Iowa | Massachusetts | New Mexico |

South Carolina |

| State health department leadership (e.g., state health official, medical director, senior deputy, etc.)b |

X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Medicaid representative | X | X | X | X | ||

| ACOG representative | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Academic medicine representative (university school of medicine/academic teaching hospital leadership) |

X | X | X | |||

| Hospital association representative | X | |||||

| Maternal and child health program representative (health department) |

X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Family planning representative (health department) | X | X | X | X | ||

| Project officer (health department) | X | |||||

| Local health department leadership (e.g., local health official, medical director, etc.) |

X | |||||

| Provider representative | X | |||||

| CDC maternal and child health epidemiology assignee (state health department) |

X | X | ||||

May include multiple members within a professional role category.

All State Health Officials and Health Department leadership are aware and approve of the learning community, but may not have participated in all calls, meetings, or sessions.

ACOG, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; LARC, long-acting reversible contraceptives.

ASTHO plans, facilitates, and leads the learning community during in-person and virtual meetings with national partners and state staff by engaging state leadership, providing expert and state-to-state technical assistance, developing meeting and virtual learning session content, and evaluating state team processes and outcomes. ASTHO also develops summary reports, state success stories, and tools outlining key themes and outcomes identified as the learning community progresses. These documents are available on the ASTHO immediate postpartum LARC webpage. The web resources are designed to benefit the members of the learning community, the public, and other state health agencies by providing practical examples of implemented policies, challenges to implementation, and successes.

CDC/DRH provides overall scientific support for the learning community, funds ASTHO to facilitate the community, and participates in discussion with state staff. This effort meets a CDC agency goal of integrating clinical care and public health, and CDC is committed to developing resources for use by all participating states.26 CMS provides technical assistance on Medicaid policy-related issues and shares resources with participating states (e.g., information about payment strategies). The learning community aligns with the Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services, Maternal and Infant Health Initiative goal: to decrease the rate of unintended pregnancies by increasing the use of effective contraception among women of childbearing age, including LARC.27 OPA supports access to LARC through the Title X Family Planning Program and the Providing Quality Family Planning Services: Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs (2014) on provision of family planning services.28 The community supports the Title X Program mission to provide individuals with the information and means to exercise personal choice in determining the number and spacing of their children, including access to a broad range of acceptable and effective family planning methods and services.29

As a supporting organization, ACOG has provided technical assistance by linking its LARC Work Group activities with the immediate postpartum LARC Learning Community.30 It has developed a practice bulletin and two committee opinions on LARC use and plans to develop materials for provider training on immediate postpartum insertion. Based on this work, other maternal and child health organizations have requested inclusion in the immediate postpartum LARC Learning Community. Developing partnerships with National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Association (NFPRHA) and the Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs (AMCHP) has provided additional support to state health department staff including resources and forums for continued discussion when developing immediate postpartum LARC policies.

Identifying domains for discussion and strategies for information exchange

In baseline interviews, the learning community identified multiple successes and challenges with immediate postpartum LARC policy implementation, including engaging stakeholders, providers, and patients; working with Medicaid for billing; training and educating providers; identifying a champion to move the policy development forward; and communicating immediate postpartum LARC availability and coverage to multiple audiences.31 The in-person kick-off meeting engaged state teams in group discussions on each of these topics and allowed learning community participants to further define each of these topical areas, participate in information-sharing about individual state experiences, and identify goals for the remainder of the learning community activity.30 Together, the group identified four goals for the learning community:

Improve state capacity to successfully implement immediate postpartum LARC by facilitating state-to-state sharing of promising strategies and common challenges;

Provide an opportunity for states to hear from ASTHO and other federal and national partners about related activities, implementation barriers, and possible solutions;

Create an opportunity for multidisciplinary state teams to identify immediate action steps for the next year; and

Highlight best practices to share with other states that are initiating immediate postpartum LARC policies.

The group also identified eight domains for focused learning events. The domains, with accompanying topics, are shown in Table 2. The states discussed the following domains, all of which will be covered before the learning community ends:

Table 2.

Domains and Topics Identified by Learning Community State Participants

| Topics | Webinar or resource |

|---|---|

| Domain: Training Providers |

Georgia provider training toolkit video and other demonstrations

|

Virtual learning sessions

|

|

| Cross-cutting training |

|

| Billing and coding |

|

| Domain: Pay Streams Title X clinics |

|

| Federally qualified health centers |

|

| Private insurers |

|

| Medicaid |

|

| Domain: Informed Consent and Ethical Concerns |

|

| Consent |

|

| Ethical concerns |

|

| Informed consent content Domain: Stocking and Supply Pricing |

TBD1

|

| Alternative funding Pharmacy |

TBD

|

| Domain: Outreach Provider |

|

| Patient |

|

| Policymaker |

|

| Domain: Partnership | |

| Federal agencies | TBD |

| National organizations |

|

| Domain: Service Location | |

| Rural/urbanTelehealth/ Clinics |

TBD |

| Domain: Data | |

| Monitoring and evaluation |

|

| Quality assurance and improvement |

|

| Access | TBD |

TBD, or to be determined, indicates an area within a domain where resource materials are not yet available.

ASTHO, Association for State and Territorial Health Officials; IUD, intrauterine device; LARC, long-acting reversible contraceptives.

1) Training: Implementing skill building for providers on immediate postpartum LARC insertion, training pharmacy staff on stocking and billing, and training administrative, pharmacy, and clinical staff on billing and coding for nonpharmacy use of LARC devices;

2) Pay streams: Understanding how Title X family planning programs approach immediate postpartum LARC, the variability in how private insurers approach reimbursement for services, and the relationship of 1115 family planning waivers and state plan amendments with immediate postpartum LARC reimbursement under Medicaid;

3) Consent: Defining timing and content of informed consent;

4) Stocking and supply: Providing concrete examples of device-stocking procedures and supply policies in both hospital pharmacies and clinics;

5) Outreach: Recruiting advocates to develop and implement immediate postpartum LARC policy by identifying effective strategies for contacting providers and policy makers, and providing examples of successful communication strategies to use with the public and clients;

6) Stakeholder partnerships: Identifying ways to engage national and federal partners on the issue of immediate postpartum LARC and determining which internal and external state partnerships are essential to successfully implementing policy;

7) Service locations: Differentiating strategies for rural and urban settings including developing engagement strategies with federally qualified health centers and family planning clinics in states; and

8) Data and surveillance: Developing more information regarding appropriate quality assurance and improvement indicators for immediate postpartum LARC and documentation on how to access existing data, particularly on safety monitoring and insertion rates.

Since planning for the initial 18-month learning community timeline only allowed for six webinars, CDC and ASTHO identified four of the eight domains for focused learning events. The first and last webinars provided states with an opportunity to share progress made on immediate postpartum LARC policy development and implementation since the beginning of the learning community. The remaining webinars focused on training, pay streams, stocking and supply, and consent domains. Each webinar contained presentations by national and state experts, an opportunity for states to discuss issues related to the targeted domain, and information sharing by federal and other national partners. All webinars and presentations were recorded and are publicly available on the ASTHO LARC website.22

At the Learning Community in-person, closing meeting, the state teams will discuss material shared during the previous sessions and will be introduced to the six new state teams that are included in the second cohort. ASTHO and federal partners will address the remaining four domains of outreach, partnership, service location, and data/surveillance during the second cohort of the learning community.

Data collection and current results to evaluate the effectiveness of the learning community

ASTHO collected qualitative and quantitative information over the course of the learning community in order to confirm that discussions were addressing the successes and challenges identified during the key informant interviews; to identify areas where federal partners could offer continued technical assistance; and to build the evidence and resource base for states interested in pursuing immediate postpartum LARC policy implementation. Baseline key informant interviews were conducted with members of each state team prior to the in-person meeting, to identify common themes for discussion during the kick-off meeting. Additional data on the targeted domain were collected during each webinar, to assess state staff opinions on issues within that domain. Participant polls were completed by individuals on state teams rather than the state team as a whole. Finally, at each subsequent webinar, the states were asked to present information on progress to change state systems within the domain presented during the previous webinar. This allowed ASTHO staff to continuously gather information on progress in each identified domain during the learning community.

Interview data collected before the opening meeting indicated that having a physician champion and specifically inviting physicians to all meetings where immediate postpartum LARC was being discussed was an important strategy to ensure clinical advocacy throughout the state. Participants also indicated during interview that provider training was a priority. States identified multiple strategies to achieve support of the clinical community, including offering continuing education credit, evaluating training effectiveness, and measuring uptake at hospitals following simulation training. Additionally, information collected during webinar sessions indicated that 40% of state team staff were meeting monthly to discuss the capacity to develop immediate postpartum LARC policy within the state, 13% of state teams were meeting weekly, and 47% were meeting as necessary to address emerging issues.

Further informational polls collecting information during learning community discussions indicated that of the reimbursements for immediate postpartum LARC, 78% were paid by Medicaid, with the remainder paid by private insurers (11%) or clients/patients (11%). In fact, the decision to provide reimbursement and publish final guidance for immediate postpartum LARC was made by the Medicaid Medical Director in most states (67%), with the remainder responding that published guidance on reimbursement was not yet available (33%). More than one-third (33%) of respondents indicated that the use of a global fee, or one fee for a set of maternity services, in both public and private insurance is a challenge for providers in their state and potentially affected their states’ ability to provide immediate postpartum LARC. Respondents also noted medical management loopholes (17%), challenges in the reimbursement process (33%), and the cost of the devices and stocking costs (17%) as barriers to provision. Additionally, the majority of respondents indicated that to date, state health departments had not created guidelines on the timing of obtaining patient consent for immediate postpartum LARC (80%). All respondents indicated that the webinar series increased their knowledge of immediate postpartum LARC payment streams and sustainability.

State accomplishments and future directions

As the immediate postpartum LARC Learning Community moves forward, participating states are engaging state health department leadership to develop important policies, protocols, and training modules to improve immediate postpartum LARC implementation. Every state in the learning community has a Medicaid policy in place for immediate postpartum LARC insertion and has published Medicaid updates, bulletins, or coding updates. Massachusetts and Colorado have created patient education fact sheets and materials, and Colorado has created an immediate postpartum LARC provider training protocol. Georgia has conducted successful trainings at residency programs throughout the state, supporting immediate postpartum LARC utilization in the future health care workforce. South Carolina hospitals are working to improve hospital capacity for immediate postpartum LARC by ensuring that clinical staff are familiar with the procedure and Medicaid policies for reimbursement. New Mexico is launching a provider education campaign in the fall of 2015 in coordination with Medicaid Managed Care Organizations to educate providers on immediate postpartum LARC reimbursement. The state staff are partnering with a telehealth program from the University of New Mexico and a provider champion to plan provision of Continuing Medical Education credits for providers. Iowa hosted graduate students from the Harvard School of Public Health to develop an evaluation plan for the Iowa immediate postpartum LARC initiative. Iowa also partnered with South Carolina to facilitate a virtual presentation on LARC practices to Iowa staff and the graduate students (Table 2).22 The CDC, ASTHO, and other national immediate postpartum LARC Learning Community partners anticipate that participating states will develop more materials through-out the duration of the learning community.

As more states begin to explore implementing immediate postpartum LARC policies, it is crucial that states familiar with this process share resources describing successes and challenges. The immediate postpartum LARC Learning Community is a first step in this direction and aims to providing organized, usable resources and information to states in a centralized, publicly available forum. CDC and ASTHO, with assistance from CMS, OPA, ACOG, AMCHP, and NFPRHA, plan to develop working guidance that all states and jurisdictions can use when considering developing and implementing immediate postpartum LARC policies. The guidance will incorporate information and resources collected during the learning community process and will be focused on the eight highlighted domains. It is anticipated that information on the four domains explored by the first cohort of states will be available the end of 2015, and the full guidance will be made available by fall of 2016.

Conclusion

An organized and structured forum for addressing a specific public health issue can integrate a systems change approach into an effective strategy for policy implementation. The immediate postpartum LARC Learning Community, consisting of national organizations, federal partners, and states, provides such a forum for developing guidance on immediate postpartum LARC policies. The learning community ongoing activities are to provide states considering immediate postpartum LARC policy implementation with resources to support communication, systems, and programmatic change and partner with states in the process of implementation by offering information addressing challenges and successes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the state teams and their participating staff for contributions to this activity. The authors would also like to thank Lekisha Daniel-Robinson, CMCS, CMS, for representing her agency and providing technical assistance to states as needed. Additionally, the authors would like to thank Loretta Gavin, OPA, and Sue Moskosky, OPA, for representing their agency in this national activity. Finally, the authors would like to thank Kristin Rankin for her input on this manuscript, and thoughtful commentary on the overall framework.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

Partial funding of this activity was provided by CDC-RFA-0173-1302. No other competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee on Gynecologic Practice; Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group ACOG Committee Opinion 450: Increasing Use of Contraceptive Im-plants and Intrauterine Devices to Reduce Unintended Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1434–1438. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c6f965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-4):1–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branum A, Jones J. Trends in Long acting reversible contraceptive use among women aged 15–44. NCHS Brief. 2015;(188):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sober S, Schreiber C. Postpartum contraception. Clin Obestet Gynecol. 2014;57:763–776. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstuck N, Steyn P. Intrauterine contraception after cesarean section and during lactation: A systematic review. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:811–818. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S53845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pickle S, Wu J, Burbank-Schmitt E. Prevention of unintended pregnancy: A focus on long-acting reversible contraception. Prim Care. 2014;41:239–260. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldwin M, Edelman A. The effect of long-acting reversible contraception on rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents: A review. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.10.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldstuck N, Steyn P. The intrauterine device in women with diabetes mellitus type I and II: A systematic review. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2013:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2013/814062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White K, Potter J, Hopkins K, Grossman D. Variation in postpartum contraceptive method use: Results from the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS) Contraception. 2014;89:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapp N, Curtis K. Intrauterine device insertion during the postpartum period: A systematic review. Contraception. 2009;80:327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J. Currrent contraceptive status among women aged 15–44: United States, 2011– 2013. NCHS Data Brief. 2014;(173):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Speroff L, Mishell D., Jr The postpartum visit: It’s time for a change in order to optimally initiate contraception. Contraception. 2008;78:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryant AS, Haas JS, McElrath TF, McCormick MC. Predictors of compliance with the postpartum visit among women living in healthy start project areas. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:511–516. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu SY, Callaghan WM, Shapiro-Mendoza CK. Postpartum care visit—11 states and New York City, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007:1312–1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hulsey TM, Laken M, Miller V, Ager J. The influence of attitudes about unintended pregnancy on use of prenatal and postpartum care. J Perinatol. 2000;20:513–519. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kogan MD, Leary M, Schaetzel TP. Factors associated with postpartum care among Massachusetts users of the Maternal and Infant Care Program. Fam Plann Perspect. 1990;22:128–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu MC, Prentice J. The postpartum visit: Risk factors for nonuse and association with breast-feeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1329–1336. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.126848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weir S, Posner HE, Zhang J, Willis G, Baxter JD, Clark RE. Predictors of prenatal and postpartum care adequacy in a Medicaid managed care population. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Washington C, Jamshidi R, Thung S, Nayeri U, Caughey A, Werner E. Timing of postpartum intrauterine device placement: A cost-effective analysis. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hernandez L, Sappenfield W, Clark C, Thompson D. Trends in contraceptive use among Florida women: Implications for policies and programs. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:S213–S221. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han L, Teal S, Sheeder J, Tocce K. Preventing repeat pregnancy in adolescents: Is immediate postpartum insertion of the contraceptive implant cost effective? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;24:e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) Maternal and child health: Long acting reversible contraception (LARC) Available at: www.astho.org/Programs/Maternal-and-Child-Health/Long-Acting-Reversible-Contraception-LARC Accessed March 16, 2015.

- 23.The Public Health System and the 10 Essential Public Health Services. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nphpsp/essentialservices.html. Accessed April 2, 2015.

- 24.Johnson K, Hays C, Center H, Daley C. Building capacity and sustainable prevention innovations: A sustainability planning model. Eval Program Plann. 2004;27:135–149. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scardamalia M, Bereiter C. Community support for knowledge-building communities. J Learn Sci. 1994;3:265–283. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Public Health Professionals Gateway: Public Health and Clinical Care Integration. Available at: www.cdc.gov/stltpublichealth/Program/resources/public.html Accessed March 17, 2015.

- 27.Daniel-Robinson L. CMCS maternal and infant health initiative. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Arlington, VA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gavin L, Moskosky S, Carter M, et al. Providing quality family planning services: Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014:1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moskosky SB. ASTHO LARC meeting. Office of Population Affairs; Arlington, VA: 2014. OPA-LARC presentation. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Association for State and Territorial Health Official (ASTHO) Long-acting reversible contraception learning community launch executive summary. ASTHO; Arlington, VA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.ASTHO LARC Learning Community . Themes from key informant interviews. ASTHO; Arlington, VA: 2014. [Google Scholar]