Abstract

The emergence of ABTs for adolescents highlights the need to more clearly define and evaluate these treatments in the context of other attachment based treatments for young children and adults. We propose a general framework for defining and evaluating ABTs that describes the cyclical processes that are required to maintain a secure attachment bond. This secure cycle incorporates three components: 1) the child or adult’s IWM of the caregiver; 2) emotionally attuned communication; and 3) the caregiver’s IWM of the child or adult. We briefly review Bowlby, Ainsworth, and Main’s contributions to defining the components of the secure cycle and discuss how this framework can be adapted for understanding the process of change in ABTs. For clinicians working with adolescents, our model can be used to identify how deviations from the secure cycle (attachment injuries, empathic failures and mistuned communication) contribute to family distress and psychopathology. The secure cycle also provides a way of describing the ABT elements that have been used to revise IWMs or improve emotionally attuned communication. For researchers, our model provides a guide for conceptualizing and measuring change in attachment constructs and how change in one component of the interpersonal cycle should generalize to other components.

Keywords: attachment-based treatments, adolescents, communication, intergenerational, internal working models

During the past decade, clinical researchers have developed and begun to evaluate attachment-based treatments (ABTs) for adolescents (Diamond et al., 2010; Moretti & Obsuth, 2009). These treatments raise questions about the defining features of ABTs for adolescents and how these features are similar to or different from the ABTs that have been developed for adults and young children (Berlin, 2008; Slade, 2008; Toth, Gravener-Davis, Guild, & Cicchetti, 2013). These questions point to the need for a framework that identifies the common features of ABTs and yet provides enough flexibility to treat different types of child, adolescent and family problems. Such a framework could also help researchers and treatment developers to measure the attachment constructs and change processes. The framework proposed in this paper begins with a review of the model of the interpersonal attachment cycle that was initially defined by Bowlby and Ainsworth and subsequently elaborated by Mary Main. This interpersonal cycle consists of three components: 1) the child or adult’s internal working model (IWM) of the caregiver’s availability and responsiveness; 2) emotionally attuned communication and 3) the caregiver’s IWMs of self and other. Together, these components reciprocally influence one another to maintain and update the caregiver and child’s IWMs.

After reviewing Bowlby, Ainsworth and Main’s contributions to the components of the secure interpersonal cycle, we use this framework to review ABTs across development, with a particular focus on ABTs for adolescents and their caregivers. We suggest that deviations in adolescence from the components of the secure interpersonal attachment cycle provide a framework for assessing family distress and establishing targets for clinical intervention. We then use the components of the secure cycle to organize the various treatment strategies that have been used to help adolescents and their caregivers revise IWMs or improve emotional communication. Research implications are discussed in the final section with a focus on how the secure cycle can be used to develop measures that are sensitive to change in IWMs or emotionally attuned communication, and that will ultimately help to identify and clarify specific mechanisms of therapeutic change

The Secure Cycle

Bowlby’s attachment theory provides an account of the intrapsychic and interpersonal processes through which attachment bonds are developed and maintained over the lifespan (Kobak et al., 2006). In this view the child IWMs contribute to the relationship by filtering interpretations of the caregiver and activating strategies for signaling attachment and motivational needs. The caregiver’s IWMs contribute to the relationship by filtering interpretations of attachment signals and corresponding caregiving strategies. These IWMs of self and other are validated or occasionally updated and revised through ongoing verbal and non-verbal communications. As a result, while IWMs provide some stability in the interpersonal cycle that maintains the attachment bond, these models remain open to developmental changes, the emergence of new relationships or to corresponding changes in the emotional communications that maintain attachment bonds. An adequate conceptualization of stability and change in a secure attachment bond requires understanding each of the three components of the interpersonal cycle: 1) a child’s IWM organized by confident expectancies in the caregiver’s as availability and responsiveness 2) ) emotionally attuned communication characterized by direct signaling of needs and accurate readings and responding to those signals; and 3) a caregiver’s IWM that facilitates sensitive responding to an individual’s attachment needs and motivational signals.

Bowlby, Ainsworth and Main each made an important contribution to conceptualizing the components of a secure interactional cycle. Bowlby (1973) introduced the child’s IWM of the caregiver as the first component of the cycle. He viewed these IWMs as organized by expectancies or forecasts for caregiver responsiveness that were derived from recurring interactions with the caregiver. Confident expectancies for caregiver availability and responsiveness organize a secure IWM and provide the basis for viewing others as trustworthy and the self as capable and self-reliant. Alternatively, negative expectancies for caregiver responsiveness lead to feelings of anxiety and self-doubt, as well as defensive, self-protective strategies. Ainsworth introduced the second component of the interpersonal cycle with her observations of emotional communication in mother-infant dyads. Her ratings of caregivers’ sensitivity to their infants non-verbal signals provided critical evidence that infants’ IWMs assessed in the Strange Situation are initially built from children’s repeated experience of emotionally attuned communication with their caregivers (Bretherton, 2013). Main’s work with the Adult Attachment Interview (IWM) provided a window on the third component of secure cycle, caregivers’ IWMs of self and other. Main and subsequent research has shown a pattern of intergenerational transmission in which caregivers with secure IWMs in the AAI were associated with their infants’ secure IWMs assessed in the Strange Situation.

Main and Goldwyn’s coding of the AAI highlighted the increased complexity of adolescents and adults’ IWMs, and helped to clarify three levels of processing important to the construction of adult representations of attachment: attachment narratives, emotion regulation strategies, and reflective processes. At the most basic level, the AAI coding system allows raters to infer adults’ expectancies for caregiver responsiveness from narratives of attachment episodes that are elicited during the AAI (Hesse, 2008). These attachment narratives have script-like structures that begin with a moment of high need (emotional upset, injury, illness) followed by a coping response (to seek or not seek support from an attachment figure) followed by an anticipated response from the attachment figure (recalled or imagined). Positive expectancies for caregiver response are indicative of a “secure base script” and are accompanied by feelings of security, while negative expectancies elicit anxious feelings (Mikulincer, Shaver, Sapir-Lavid, & Avihou-Kanza, 2009; Waters, Brockmeyer, & Crowell, 2013). Ratings of expectancies for mothers and fathers derived from the AAI Q-sort have been shown to form distinct constructs from states of mind scales (Kobak & Zajac, 2009; Haydon, Roisman, & Marks, 2011; Waters et al., 2013).

At a second level of analysis, raters can infer “rules for processing attachment information” from interview transcripts (Hesse, 2008). These rules or strategies allow an individual to “preserve a state of mind with respect to attachment” (Main et al., 1985). Secure individuals who can flexibly attend to interview topics are judged as more coherent and as “free to evaluate” attachment. By contrast, more rigid or defensive strategies produce violations in maxims for coherent discourse (Grice, 1991) and provide raters with the basis for inferring a Dismissing or Preoccupied state of mind (Main & Goldwyn, 1998). These “secondary strategies” are thought to protect the individual from anxious feelings that accompany negative expectancies (Main et al., 1985) and may also reduce potential conflict with the caregiver (Main & Weston, 1981).

Main also identified a reflexive level of processing that co-occurred with confident expectancies and secure states of mind (Fonagy, Steele, & Steele, 1991; Main, 1991). The AAI tests this reflexive level with questions that require participants to integrate episodic attachment narratives into a more general understanding of self and caregivers. These questions ask participants to step back and to compare past and present perspectives on relationships, discuss how views of caregivers have changed over time, and think about caregivers’ intentions and motivations for behaving as they did as parents. The reflexive or meta-cognitive level of processing introduces the possibility of bringing implicit expectancies into awareness and, of considering new information, alternative perspectives and ways of revising outdated expectancies. This reflexive level of processing is an active ingredient in mentalization-based treatments that emphasize gaining new understandings of the minds of others (Sharp & Fonagy, 2008).

The Secure Cycle and ABTs Across the Lifespan

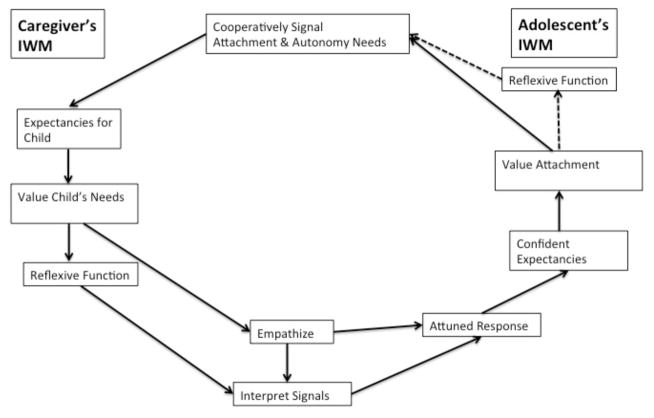

We believe that the secure cycle provides a general framework for assessing distressed attachment bonds and establishing treatment goals for ABTs for children, adolescents, and adults (see Figure 1). This framework is general enough to describe Bowlby’s (1988) attachment-based psychotherapy for adults as well as two of the more recent ABTs for the caregivers of infants and young children. In spite of enormous developmental change, the different components of the secure cycle (caregiver IWMs, emotional attunement, IWMs of the caregiver) provide a general description of the interpersonal processes required to maintain a secure attachment bond. This interpersonal cycle, in turn, provides treatment developers considerable flexibility in choosing targets for intervention, treatment modalities and intervention techniques. Reflection and conscious awareness of IWMs may be an essential mechanism of change in some ABTs and much less so in others.

Figure 1.

The Secure Interpersonal Cycle for Caregiver-Adolescent Relationships

Treatments for Adults

Bowlby’s training as a psychoanalyst predisposed him toward applying attachment concepts to individually oriented treatment for adults. His quote from the Separation volume of his attachment trilogy illustrates his view that reappraising IWMs of self and others is the overarching goal of ABT for adults. However, Bowlby (1973: 1988) viewed the process of revising IWMs as occurring in the context of ongoing communication, in which the therapist attends to the client’s verbal and non-verbal signals, empathically reflects the client’s motivational states and serves as a secure base for reflection and reevaluation. Bowlby’s view of treatment dovetails with Main’s view of IWMs. Because IWMs operate automatically and implicitly guide attachment behavior, a central task of therapy was to encourage clients to bring IWMs into awareness so that their validity could be tested and reevaluated. Establishing a secure therapist-client relationship was a precondition for revising IWMs. At a procedural level, the therapist establishes a secure relationship by acting as an empathic caregiver, by accepting the client’s distress, and by encouraging the client’s exploration and development. In addition to providing the adult client with an empathic caregiver, the therapist guides conversations towards the client’s attachment-related experiences so that the interactions generalized to form the core of IWMs become available for reflection and evaluation (Stern, 1985). As clients communicate implicit procedural memories in words, they can begin to identify and reflect on IWMs. Bringing these models into the therapeutic conversation, in turn, creates further opportunities to consider alternative views of self and others and to test the validity of existing IWMs in current interactions with significant others.

Therapeutic efforts to update or revise IWMs may target each of the three levels of processing identified by Main (expectancies, emotion regulation strategies, reflective function). As clients develop confident expectancies in the therapist’s availability and responsiveness, clients can feel more secure, acknowledge attachment needs, and evaluate how negative expectancies contribute to relationship difficulties. In this process, the therapist helps the client to identify the defensive processes that maintain states of mind and to contain the negative or painful emotions that accompany negative expectancies. By eliciting attachment narratives, the therapist encourages the client to find words and images for the expectancies and disowned attachment feelings. In making implicit expectancies, emotions, and defenses available for inspection, the client can reflect and evaluate IWMs in light of their consequences and consider alternative ways of perceiving and responding to attachment needs in self and others. In this treatment model, emotional communication with an empathic therapist provides the context for making implicit assumptions explicit and using reflection and revaluation to develop more secure expectancies for self and others.

Treatments for Young Children

The Circle of Security program (COS) developed a model of the secure cycle that guides intervention with caregivers of young children (Marvin, Cooper, Hoffman, & Powell, 2002). In doing so, they specified the cycle to capture the young child’s needs for exploration (the bottom half of the circle) and protection (the top half of the circle). The COS program aims to increase security in the attachment bond by targeting the caregiver component of the secure cycle with the goal of helping caregivers revise their IWMs of the child. Because infants and young children’s’ IWMs are presumed to be highly malleable and sensitive to the caregiving environment, success in revising caregivers’ IWMs or in improving communication would presumably lead to more secure IWMs in the child. Change in the child’s IWMs should, in turn, support the child’s ability to communicate and signal attachment and exploratory needs to the caregiver. This dual focus on revising caregivers’ IWMs of the child and on improving emotional attunement in the caregiver-child dyad added an important new treatment target for ABTs.

The COS program helps caregivers revise their IWMs of the child by introducing caregivers to alternative ways of attending to, interpreting and subsequently responding to the child’s signals (Powell, Cooper, Hoffman, & Marvin, 2013). COS begins with a careful analysis of the caregiver’s ability to attend to their child’s signals, using videos of caregiver-child interactions as an assessment tool. This helps the therapist to formulate the central “lynchpin” struggle, or organizing theme, that interferes with the caregiver’s ability to help the child organize emotions, provide comfort, and support exploration. Next, the intervention helps caregivers identify expectancies or perceptions of the child that lead to mistuned responses and defensive processes (i.e., “shark music”) that maintain these distorted perceptions and the lynchpin struggle. Having identified a central treatment focus, the COS intervention draws on and translates core principles from Bowlby’s theory of change and Main’s multi-level conceptualization of IWMs. The therapist addresses the caregiver’s negative expectancies by modeling attuned caregiving through the therapeutic relationship. As caregivers observe video replays of their interactions with their child, they are coached to empathize with and label painful emotions that maintain their defenses. Through this process they begin to and establish more reflective dialogue about their child and their caregiving role, and, the therapist is in the position to open the caregiver’s IWMs of the child to new information and points of view. This reflective dialogue is designed to increase the caregiver’s awareness and tolerance of the discomfort and sensitivities that interfere with their ability to accurately observe and sensitively respond to their child’s cues and miscues.

The Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC) intervention targets the communication component of the interpersonal cycle by coaching caregivers toward more emotionally attuned responses to the child’s signals (Bernard et al., 2012; Bernard, Meade, & Dozier, 2013). The ABC therapist coaches caregivers by identifying and reinforcing “in the moment” behaviors that occur spontaneously during the caregiver’s interaction with the child. Three behaviors are targeted for reinforcement: nurturance, following the child’s lead, and delight, while the frequency of frightening behaviors are reduced by bringing them to the caregivers’ awareness (Bernard et al., 2012).

An increase in the positive behaviors and decrease in frightening behaviors increases the level of emotional attunement in the relationship, which, in turn, has been found to increase the security and organization of the child’s IWM in the Strange Situation (Bernard et al., 2012). The ABTs developed for infants and young children added new approaches to improving emotional attunement in the caregiver-child dyad. Both COS and ABC have defined and assessed how mistuned caregiver responses to children’s signals contribute to anxious attachment. These treatments differ, however, in how they choose to intervene in the caregiver-child dyad. COS seeks to improve emotional attunement by assessing and respectfully challenging the caregiver’s IWMs of the child. By helping caregivers to differentiate between responses that are attuned to the child’s needs and miscues that reduce empathic responding, COS seeks to revise the caregiver’s IWM of the child in ways that improve accurate and empathic responding to attachment and exploratory needs. By contrast, ABC directly coaches caregivers in how to read and respond to their child’s signals. Presumably, changes in a caregiver’s IWMs produced in the COS program leads to change in caregiver-child communication, whereas changes in communication produced by the ABC program results in change in the caregiver’s IWM of the child.

Treatments for Adolescents—Developmental Change in the Secure Cycle

There are several developmental changes that must be accommodated in order to make the secure cycle clinically useful with adolescents and their caregivers. First, by adolescence, youth have become more active partners in maintaining the attachment bond as a goal-corrected partnership. Adolescents’ increased role in maintaining the interpersonal cycle is evident in their more complex and established IWMs of self and caregiver. Not only are IWMs more complex during adolescence but also they are more resistant to change compared to early childhood (Bowlby, 1973). As a result, insecure features of the adolescent’s IWM, such as negative expectancies, difficulties with emotion regulation and limitations in reflective capacity, play a larger role in maintaining relationship distress. The adolescent’s more active role also alters the nature of communication in the secure cycle. Goal conflicts become more normative and emotional attunement now requires conversations to cooperatively negotiate goal conflicts (Kobak & Duemmler, 1994). Emotionally attuned communications are evident when adolescents engage in conversations that directly signal their autonomy needs while valuing and respecting the caregiver’s concern for their safety and well-being. Conversations in which both partners acknowledge or mentalize each other’s perspectives facilitate cooperative negotiation of conflicting goals.

The biological changes associated with puberty also alter adolescents motivational systems. Exploratory needs change dramatically with the activation of the sexual system and increased desires to affiliate with peers (Kobak, Rosenthal, Zajac, & Madsen, 2007). As a result, the adolescent increases time away from parents and returns to the caregiver with less intensity and frequency. This interplay between the adolescent’s attachment, affiliative and sexual motivational systems fosters increasingly autonomous or self-regulated activities that are beyond the caregiver’s supervision or direct guidance. Caregivers continue to monitor adolescents’ safety, but their monitoring becomes increasingly reliant on the adolescent’s willingness to disclose and share their activities with the caregiver (Smetana, 2010). As adolescents autonomy and engagement in close peer relationships develop, attachment needs are less frequently activated and become more limited to emergency situations and moments of high need or distress (Kobak, et al., 2007). These developmental changes in the child call for complementary changes in the caregiver role. The caregiver’s IWM of the adolescent also become more complex and requires balancing respect for the adolescent’s autonomy with the continuing need to protect the adolescent from danger and risky behaviors. Conversations with the adolescent become important for the caregiver’s IWM insofar as they are needed to monitor the adolescent’s safety and empathize with the adolescent’s perspective.

As a result of these developmental changes in the secure cycle, ABTs for adolescents occupy a middle ground between treatments for adult and young children. Drawing from ABTs for the caregivers of young children, therapists treating adolescents may choose either to help parents revise their IWMs of the adolescent or to work with the caregiver-child dyad to increase emotionally attuned communication. However, treatments for adolescents may also draw from ABTs for adults that use individual therapy to revise adolescents’ IWMs of themselves and their caregivers. These three treatment modalities each offer a unique set of targets for assessment and intervention (see Table 1). Treatments that target the caregiver or adolescent’s IWMs must initially assess how the expectancies, regulatory strategies, or reflexive components of those models contribute to presenting problems or relationship difficulties. Similarly, treatments that focus on emotional communication in the caregiver-adolescent dyad must identify patterns of interactions that reduce the adolescent’s ability to use the relationship as a source of protection and support.

Table 1.

Treatment Targets, Mediators and Outcomes in ABT’s for Adolescents

| Treatment Modality & Target | Treatment Element | Mediator | Attachment Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver’s IWM | |||

| Negative View of Self | Therapist’s Empathic Responding | Increased felt security and reflective capacity | Increased caregiving efficacy |

| Negative View of Adolescent’s Problem Behavior | Reframing, Psychoeducation | Increased recognition of adolescent’s attachment needs | Increased positive engagement |

| Defensive Emotion Regulation | Eliciting Caregiving and Attachment Narratives | Episodic memories accompanied by emotion processing | More empathic and attuned responding |

| Reduced Reflexive Function | Reflective Dialogue, Video Replay, Psychoeducation | Statements indicating a distanced perspective on self and other | Improved problem solving and emotion regulation |

| Adolescent’s IWM | |||

| Negative Expectancies for Caregiver | Therapist’s Empathic Responding | Increased felt security and reflective capacity | Increased confidence in self and others |

| Restricted Emotion Regulation | Eliciting Attachment Narratives | Access to primary attachment needs and feelings | Valuing of attachment needs and feelings |

| Reduced Reflexive Function | Reflective Dialogue | Third party perspective on relationship | Improved problem solving and emotion regulation |

| Communication | |||

| Unresolved Goal conflicts | Communication Coaching | Improved perspective taking and signaling of needs | More Cooperative Conversations |

| Empathic Failures | Circular Questioning | Increased checking of interpretations of self and other | Improved accuracy of IWMs |

| Attachment injuries | Injury-Repair Episodes | Increase in validation cycles | Increased confidence in caregiver |

Assessing and Treating Adolescent Psychopathology

Deviations from the Secure Cycle: Attachment Injuries, Empathic Failures, and Mistuned Communication

By identifying deviations from the secure cycle with adolescents and linking them to adolescents’ symptoms and family distress, therapists can identify potential targets of intervention (see Table 1). For instance, by attending to how adolescents describe interactions with their caregivers, therapists can begin to identify negative expectancies that deviate from the secure base script or strategies that restrict or distort painful or difficult emotions and reduce reflective capacity. Helping adolescents to explore and narrate painful episodes in which the caregiver was unavailable, unresponsive, or rejecting provide the basis for assessing the severity of an adolescent’s attachment injuries. Therapists can help adolescents to make thematic connections between attachment episodes, making implicit negative expectancies that organize their IWMs a potential target for treatment.

Therapists may also use caregivers’ narratives of interactions with their adolescent to assess the caregiver’s IWMs of the adolescent. Narratives of how caregivers respond to their adolescent’s problem behaviors may reflect non-empathic or hostile views of adolescent and failure to recognize the adolescent’s attachment, exploratory, or relational needs. These empathic failures, in turn, may contribute to negative cycles of interaction that reduce the caregiver’s ability to reflect and consider alternative interpretations of the adolescent’s behavior and motivations.

Therapists may also assess deviations from the secure cycle in observations of mistuned emotional communication between adolescents and caregivers. Caregivers’ negative interpretations of their adolescents’ behavior often fuel their feelings of anger or helplessness and contribute to hostile or disengaged responses to the adolescent’s attachment and autonomy needs. These empathic failures, in turn, increase risk for attachment injuries and confirm the adolescent’s negative expectancies for the caregiver’s availability and responsiveness. The adolescent’s defensive responses to attachment injuries often result in angry, disengaged, or symptomatic expressions of attachment needs that further confirm the caregiver’s negative interpretations of the adolescent. The caregiver and adolescent’s failed attempts to establish emotionally attuned communications often contribute to a symptomatic cycle of coercive or disengaged exchanges that undermine mutual trust in the caregiver-adolescent relationship (Miccuci, 2009). As a result, the adolescent cannot use the relationship to effectively manage stress or to support exploration and developmental change.

The secure cycle not only guides assessment of mistuned communication and insecure IWMs that contribute to attachment disturbances, but it also provides the therapist with a map for revising IWMs and improving emotional attunement in attachment dyads. In many respects, the goal of treatment is to create experiences that are more closely aligned with the prototype provided by the secure cycle. This may occur not only by helping adolescents and their caregivers increase their awareness of how negative expectancies and defensive processes contribute to their distress, but also by providing opportunities for clients to recall and enact experiences that conform to the secure base script or opportunities for emotionally attuned conversation resulting in a sense of mutual understanding between the caregiver and adolescent. The secure cycle thus serves both a diagnostic and therapeutic function.

Treatment Elements for Adolescents--Toward a Theory of Change

With the three components of the secure cycle as a framework, ABTs for adolescents can draw upon and further specify treatment elements that have been used to revise adult’s IWMs, as well as treatment elements that have been used to improve emotional attunement in caregiver-child treatments. Four key elements have been included in treatments that target IWMs: 1) implicit modeling of secure attachment; 2) emotional processing of attachment narratives; 3) reflective dialogue; and 4) psychoeducation. Treatment elements that focus on improving emotional attunement between caregivers and children draw from the literatures on family therapy (Nichols, 2012) and caregiver-infant interaction (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Stern, 1985). These treatment elements include 1) communication coaching, 2) enactments of injury-repair episodes, and 3) reflective conversation. Although most ABTs employ multiple treatment elements, our goal in distinguishing components of these treatments is to allow for systematic testing of the effectiveness of specific components in producing change in attachment relationships.

Revising caregiver or adolescent IWMs

“In terms of the present theory much of the work of treating an emotionally disturbed person can be regarded as consisting, first, of detecting the existence of influential models of which the patient may be partially or completely unaware, and, second, of inviting the patient to examine the models disclosed and to consider whether they continue to be valid.” (Bowlby, 1973, p. 205).

Implicit modeling of a secure relationship

The client’s relationship with the therapist is both a precondition and a potential mechanism of change in the client’s IWMs (Bowlby, 1988). As a precondition, revision of IWMs can only occur when the caregiver or adolescent has a secure base from which to explore new perspectives and information. A relationship with an attuned therapist can provide the caregiver or adolescent with a sense of being understood and validated in ways that support more confident expectancies for self and others. These positive expectancies for the therapeutic relationship are tested by the therapist’s ability to manage the client’s emotional distress and to provide timely guidance. Clients’ confidence in the therapist should increase their willingness to narrate attachment injuries and explore alternative ways of interpreting their own and others’ behavior. At an implicit or procedural level, the therapeutic relationship provides the client with an experience of positive expectancies that support emotionally attuned communication.

The therapist may also use the relationship to help clients compare their experience with the therapist to their experiences in current and past relationships with significant others. As clients bring implicit and procedural aspects of their IWMs into conversation with the therapist, they are in a better position to revise existing IWMs in light of positive experiences with the therapist. The ongoing tension between implicit negative expectancies that organize IWMs and a positive relationship with the therapist may also become evident in alliance ruptures or moments when the client anticipates or experiences lack of availability or rejection from the therapist. Therapists may help client’s identify and discuss these attachment injuries to illustrate how sharing these moments can lead to conversations that restore trust in the therapist (Safran & Segal, 1990). If the therapist effectively manages these moments, alliance ruptures provide opportunities for the client to revise outdated IWMs.

Narrative change and emotion processing

Eliciting attachment and caregiving narratives creates the opportunity for adolescents and parents to re-experience and better understand primary attachment emotions. Therapists may play an active role in emotional processing by helping clients to contain, reframe, and effectively manage attachment-related feelings of fear, anger, or sadness. Greenberg’s emotion focused therapy distinguishes between primary emotions that play an adaptive function for the individual from secondary emotions that generally serve a defensive or self-protective function that reduces effective adaptation (Greenberg, Auszra, & Herrmann, 2007). When an individual recalls attachment episodes that follow the secure base script, they are likely to experience primary attachment emotions. The secure base script begins with a moment of high need that activates primary attachment emotions ranging from fear to sadness. These emotions motivate attachment behaviors and contact-seeking with an attachment figure. If the individual encounters obstacles to gaining access to or a response from an attachment figure, they may experience anger as the primary attachment emotion. Anger can motivate the individual to overcome obstacles or alert the caregiver to the importance of the relationship. These primary attachment emotions of fear, anger, and sadness motivate adaptive behavior and directly signal the child’s needs to available caregivers. As a result, they serve to restore access to a responsive caregiver, confirm positive expectancies for the caregiver’s availability, and result in secure feelings.

In the absence of a secure attachment, secondary emotions serve a self-protective function. Repeated attachment injuries and empathic failures activate secondary defensive strategies that systematically distort the expression of attachment-related feelings. As a result, the adolescent may attempt to hide feelings of vulnerability and hurt to minimize these painful feelings and deactivate the attachment system in an effort to avoid further attachment injuries. Alternatively, some adolescents may actively amplify feelings of fear, anger, or sadness in an attempt to engage non-responsive caregivers (Kobak et al., 1993). Primary emotions of anger, sadness, and anxiety are then expressed in distorted or secondary forms that are likely to miscue caregivers about the adolescent’s attachment needs. Anger about lack of availability may be expressed as hostility that further distances caregivers. Sadness at loss of a relationship may be expressed as depressed mood and withdrawal that may be interpreted as a lack of interest in maintaining the relationship with the caregiver. Fear may become generalized anxiety or phobias that are not amenable to caregivers’ attempts to provide comfort or support. These secondary emotions or distorted signals often increase empathic failures in ways that exacerbate or maintain the adolescent’s symptoms and problem behaviors.

Narratives that conform to the secure base script allow the therapist to reinforce the client for acknowledging feelings of vulnerability and valuing attachment needs. By validating these primary attachment emotions, the therapist increases the client’s ability to acknowledge the attachment needs for support and encouragement and directly signal these needs to caregivers. Narratives that deviate from the secure base script provide a context for reframing secondary emotions of hostility, depression, and anxiety as distorted expressions of primary attachment needs. This requires increasing the client’s awareness of and exposure to primary attachment emotions involving hurt and vulnerability while calling attention to how self-protective or defensive processes interfere with communicating primary attachment needs. By accessing primary attachment emotions, clients are more likely to be motivated to engage others in ways that reduce conflict and result in more empathic responses from caregivers.

Reflective dialogue—Conversation as a mechanism of change

Making IWMs the object of attention and a topic for therapeutic conversation may be a common feature to all ABTs. This requires clients to use their reflective capacities to engage in meta-cognitive thinking about how implicit expectancies that organize their IWMs guide their perceptions and interpretation of behavior in themselves and others. While much of emotion processing is based on encouraging clients to acknowledge and value attachment-related feelings and bring them under greater cognitive control, reflexive functioning centers more on meaning making or drawing inferences from the emotions and behavior. Reflexive function begins when these automatic implicit inferences are made explicit through reflective dialogue. Once the interference is brought to the client’s attention they can then be opened to alternative interpretations and perspectives. The overall goal of reflective dialogue is to help the adolescent or caregiver establish a “self-distanced” stance toward oneself and others that recognizes the “opaqueness” of one’s own and others’ minds. This perspective or stance places the client in a position to consider and evaluate alternative interpretations and perspectives of both self and others.

Therapists may establish reflective dialogue in a variety of ways. These include eliciting caregiver’s interpretations of their child’s behavior during video replay (Hoffman, Marvin, Cooper, & Powell, 2006; Oppenheim & Koren-Karie, 2013) reframing adolescent symptoms as a relationship rather than an individual problem (Moran, Diamond, & Diamond, 2005); and didactic presentations that emphasize how conflict may be a distorted expression of adolescent’s attachment and autonomy needs. The therapist directs these conversations by using the prototype of the secure cycle to suggest new perspectives and alternative interpretations of behavior that more accurately reflect the adolescent’s or child’s attachment and autonomy needs. The process of video review has been most fully elaborated in the COS protocol, which integrates assessment of the caregiver’s IWMs of the child with increasing the caregiver’s awareness of areas of discomfort that inhibit their ability to read and respond to their child’s needs. Reflective dialogue in the COS protocol addresses implicit rules that organize the caregiver’s IWM of self, while altering the caregiver’s IWM of the child and how the caregiver perceives and responds to the child’s behavior. Some of these methods for establishing reflective dialogue could be readily adapted for working with the caregivers of adolescents.

Psychoeducation

Psychoeducation makes explicit use of the secure cycle not only to frame treatment goals but also to introduce clients to new information with which they can revise and update existing IWMs. The Connect program illustrates the value of explicitly teaching core principals of attachment to the parents of anti-social adolescents (Moretti & Obsuth, 2009). After introduction to key principles of the secure cycle (i.e., children’s attachment and autonomy needs; how expression of these needs change with development; how negotiating goal conflicts is required to maintain a secure partnership; how a secure relationship depends on the caregiver’s capacity to empathize with the child’s needs), participants reflect on how these principles can be understood in their own experience and practiced in role plays. The second part of the Connect program focuses on helping caregivers recognize their own needs and how to balance their needs with the needs of their adolescents. Providing psychoeducation in group contexts supports revision of caregivers’ IWMs of themselves and their children by developing group norms that support the prototype provided by the secure cycle.

Much of the effectiveness of psychoeducation depends on repeated exposure to new information and opportunity to practice new skills. ABTs use the secure cycle to develop and repeat alternative interpretations of problematic behavior and symptoms. Repeated and explicit use of the prototype of the secure cycle with distressed families characterized by high levels of negative exchanges can defuse negative affect and help caregivers and adolescents consider alternative and more constructive ways of interacting. A central contribution of psychoeducation is that it directs a family’s attention to how they can improve their relationships. In doing so, the prototype of the secure cycle provides caregivers and adolescents who are motivated to change with clear guidance as to how to improve their relationships. By establishing a clear and explicit model of what secure relationships look like, both caregivers and adolescents are provided with a sense of direction, optimism and hope. These may prove to be the active ingredients required for revising negative models of self and others.

Improving emotionally attuned communication in ABTs for adolescents

“A well known observation, which in the world of psychotherapy has perhaps been taken too much for granted without its theoretical implications being given sufficient attention, is the constant interaction of, on the one hand, patterns of communication, verbal and non-verbal, that are operating within an individual’s mind and, on the other, the patterns of communication between him and those whom he feels he can trust.” (Bowlby, 1991, p. 294)

The goal of ABT therapists working directly with caregiver-adolescent dyads is to increase emotionally attuned communication. The notion of increasing emotional attunement is closely tied to increasing the caregiver’s recognition and responsiveness to the adolescent’s needs for comfort, guidance, autonomy and occasional assistance in regulating emotions and behavior. Conversely, mistuned caregiver communication encompasses poor responsiveness to the adolescent’s attachment needs (e.g., neglect, withdrawal, low warmth), failure to respond to and support the adolescent’s autonomy (e.g., intrusiveness, overprotection), as well as difficulties with monitoring and meeting the adolescent’s need for adult guidance. Relationships in which the caregiver fails to provide continued guidance leave the child vulnerable to role confused and controlling behaviors (Obsuth, Hennighausen, Brumariu, & Lyons-Ruth, 2013). Therapists work to improve the caregiver’s ability to recognize and respond to the adolescent’s needs while simultaneously helping the adolescent to signal those needs effectively and acknowledge the caregiver’s point of view. Reflexive conversations, coaching and reparative enactments are approaches to improving emotional attunement that derive from different traditions of family therapy.

Reflexive Conversation

Eliciting reflexive conversation in the context of family and caregiver-adolescent discussions can be accomplished by punctuating moments of reflective functioning and asking family members to identify, share, and question assumptions about one another. Drawing on family therapy approaches (Selvini, Boscolo, Cecchin, & Prata, 1980), Fearon and colleagues have developed Mentalization-Based Treatment for Families (MBT-F), a protocol that provides therapists with a way of using their own observations of family interactions to move family members toward a reflective stance on their interactions. MBT-F specifies a loop that begins by the therapist noticing and naming an interaction. Checking involves testing the validity of the therapist’s observation with family members by acknowledging the therapist’s labeling of the interaction is tentative and possibly incorrect. Through a repeated cycle of noticing and mentalizing the moment, therapists can help family members to identify common triggers for negative interactions and consider alternative understandings of each other (Fearon et al., 2006; Keaveny, Midgley, Asen, Bevington, & Fearon, 2012). This approach views change as an iterative process in which family members gradually revise their IWMs through establishing a tentative or reflective stance toward other family members in a way that encourages more open communication and a reduction of misunderstandings. ABTs provide some specification to this approach insofar as the secure prototype would guide the therapist in noticing how attachment injuries or empathic failures may be contributing to negative patterns of family interactions.

Coaching

Communication coaching “in the moment” during adolescent-parent interactions can serve to reinforce attuned moments and interrupt and redirect mistuned interactions. Therapists trained in this technique observe and punctuate positive interactions and are likely to be most effective when they have the ability to clearly identify attuned and mistuned communication. Like other interventions for young children (e.g., Parent-Child Interaction Therapy, ABC), the in-the-moment comments work to actively shape caregiver behavior in ways that can increase the adolescent’s sense of the caregiver’s sensitivity to their signals. By adolescence, coaching must be adapted to shape the adolescent’s ability to identify and share their needs and goals with parents. Many adolescents protect themselves from the feelings of hurt that accompany their negative expectancies by disengaging from parents, seeking support from peers, or becoming hostile and non-compliant during normal negotiation of goal conflicts. As a result, these defensive strategies distort or miscue their caregivers about underlying attachment or autonomy needs. Autonomy-related conflicts are common, and, in these contexts, adolescents can be coached how to articulate and negotiate their goals with caregivers.

Reparative Enactments

Enactments of injury and repair episodes provide an innovative approach to coaching on-line communication with adolescents and caregivers. This approach requires the therapist to focus attention on an adolescent’s IWM and to identify an attachment injury that supports negative expectancies and defensive strategies that restrict open communication in the attachment dyad (Johnson, Makinen, & Millikin, 2001). Once an attachment injury is identified, the therapist orchestrates a repair episode. This sequence requires that the adolescent share the injury with their caregiver and that the caregiver validates and empathizes with the adolescent’s experience and associated vulnerable emotions. This may require the caregiver to acknowledge past failures to respond to the adolescent at times of high need. When therapists are successful in choreographing these injury and repair episodes, they provide the opportunity for the adolescent to experience support from the caregiver and for the caregiver to understand the vulnerabilities that may motivate defensive and miscued communications.

Diamond and his colleagues have developed the injury and repair approach in their Attachment Based Family Therapy (ABFT) for the treatment of depressed and suicidal adolescents (Diamond et al., 2010). Their treatment begins by asking the adolescent why they are unable to go to their caregiver(s) for comfort and support when they are feeling suicidal. Individual sessions with the adolescent are then used to explore the adolescent’s IWMs and identify attachment injuries, while individual sessions with the caregiver prepare them to better respond and empathize with the adolescent (Moran et al., 2005). During the next phase of treatment, family sessions allow the therapist to choreograph injury and repair interactions that provide the caregiver and adolescent with further opportunities to revise and update their IWMs. Following the repair episodes, improving communication remains the focus of treatment, providing the adolescent further opportunities to articulate and negotiate attachment and autonomy needs. In this respect, ABFT is a multi-modal treatment that combines an individual focus on revising IWMs with communication training. Compared to other reinforcement or practice-based mechanisms of change, accessing primary attachment emotions associated with attachment injuries points to exposure as a potential mechanism of change (Carey, 2011).

ABTs differ in the degree to which they attempt to bring about change through implicit/procedural processes or more explicit verbal reflection and declarative knowledge. Learning theory suggests that IWMs can be revised through reinforcement and extinction processes that do not require conscious reflection. Similarly, when a therapist models a secure relationship that provides the client with more positive expectancies and feelings of security, these therapeutic benefits occur without need for the client’s conscious awareness or reflection. Presumably, the client’s experience of more attuned interactions with the therapist provides the basis for gradually revising negative expectancies and increasing an overall level of felt security. This, in turn, may open models of self and other to reflection and revision. However, these effects on emotion regulation and reflection are likely to be subtle and not a specific intervention target. By contrast, treatment elements such as reflective dialogue and psychoeducation use declarative and explicit verbal processing to revise IWMs. These approaches either seek to make implicit expectations explicit through conversations with the therapist or provide clients with an explicit model of the prototype of the secure cycle that can be used as a guide for developing more effective communication skills. The effectiveness of these approaches is likely to depend on the degree to which they are practiced and made part of implicit/procedural components of IWMs.

ABTs also differ in how much interventions focus on building new skills, as opposed to how much they target the negative emotions that motivate defenses and restrict attention to attachment needs. Some ABTs primarily focus on building the competencies and skills required to maintain a more secure attachment bond. For instance, ABC and Connect primarily focus on developing skills needed to maintain more attuned communication and empathic understanding and share an emphasis on providing the client with positive experiences and new skills for maintaining attachment relationships. An alternative view of change places more emphasis on helping clients to access narratives of attachment injuries that support insecure IWMs and how the associated painful feelings contribute to current relationship difficulties. For instance, building on the work of (Fraiberg & Fraiberg, 1980), Bowlby viewed therapy as a context in which painful feelings associated with negative expectancies for self and others can be safely re-experienced and acknowledged. Similarly, ABFT encourages adolescents to generate narratives of attachment ruptures and motivates adolescent-parent dyads to initiate and engage in reparative interactions with one another. Exposing adolescents and caregivers to the painful emotions associated with attachment injuries also requires therapists to attend to how clients defend against those feelings. In addition, therapists must address defensive strategies such as dismissing/avoidance or preoccupied/rumination to open IWMs to revision or to improve emotional attunement.

Developing the Evidence Base for ABTs for Adolescents

In spite of substantial progress in developing ABTs, the evidence base for these treatments remains underdeveloped. Only a few ABTs have demonstrated efficacy in randomized clinical trials and questions remain about replication, the nature of control conditions, and how the success of these treatments is conceptualized and assessed (Berlin, 2008). ABTs designed for older children, adolescents, or adults face the additional challenge of demonstrating their efficacy, not only in changing attachment, but also in reducing psychopathology and symptoms, which are the primary outcomes examined in research on evidence-based treatments for adolescent and adult disorders.

A first step in testing ABTs is to develop measures and research designs that are capable of capturing subtle changes in the most proximal targets for intervention. Capturing change in IWMs and caregiver-adolescent communication will require close attention to how individuals narrate their experience in relationships, dimensional ratings of states of mind, and intensive longitudinal designs that use relatively brief but frequently repeated measures. For instance, if the primary goal of a psychoeducational program for caregivers is to change negative expectancies of their adolescents, then measures that capture change in expectancies are needed. Indicators of change in expectancies could include coding of caregivers’ narrative descriptions of adolescent behavior from primarily negative to more empathic interpretations. Promising attempts have been demonstrated for the Connect program in that participation in Connect is associated with pre-post reductions in caregiver reports of adolescent problem behaviors and in positive changes in interview assessments of caregivers’ IWMs (Moretti & Obsuth, 2009). Similar assessment approaches may also be used to examine change in adolescents’ IWMs with a particular focus on the degree to which pre-post assessments of attachment narratives change toward a secure base script. Finally, if the adolescent’s negative expectancies for caregiver availability and responsiveness are targeted, attachment narratives generated before and after treatment should show a shift toward more positive expectancies that are reflected in the secure base script (Mikulincer et al., 2009; Salemink & Wiers, 2011).

Assessment of change in emotion regulation and defensive strategies may be principally guided by dimensional assessment of states of mind with respect to attachment. If Dismissing or Preoccupied states of mind restrict an individual’s ability to access, acknowledge and integrate attachment-related emotion into narratives of attachment episodes, an adolescent’s ability to generate narratives of attachment injuries becomes indicative of improved emotion regulation (Berking et al., 2008; Chambers, Gullone, & Allen, 2009; Kross & Ayduk, 2011; Kross, Ayduk, & Mischel, 2005). Movement toward the secure prototype is indicated by the adolescent’s ability to access feelings of vulnerability at appropriate times with a corresponding valuing and accepting of attachment needs as legitimate. Dimensional assessments of Dismissing and Preoccupied states of mind derived from AAI transcripts may be sensitive to changes toward more secure states of mind AAI (Kobak & Zajac, 2011). For instance, subtle reductions in Dismissing strategies may be evident in increased ability to value attachment and access memories that adhere to the secure base script. Change in Preoccupied strategies may be evident in an individual’s ability to contain anger toward an attachment figure and accept a caregiver’s limitations in ways that clarify the boundary between self and other.

Efforts to measure an adolescent or caregiver’s reflective function are challenged by how this capacity fluctuates in response to context and the individual’s emotional state. Reflective function is employed throughout most treatment modalities, and therapists often encourage family members to assume a reflective stance during treatment. However, it is important to differentiate momentary improvements in reflective capacity that occur with support from the therapist from the individual’s ability to spontaneously adopt a reflexive stance during moments of caregiver-adolescent interaction outside of therapy. Presumably, successful intervention provides clients with repeated opportunities to practice establishing a reflective stance and considering alternative perspectives, even (and maybe especially) during moments of high distress. Thus, it may be particularly important to measure reflective function at moments of high challenge. Standardized contexts such as the AAI or video-replay may be useful in measuring individual reflective capacities, but it remains uncertain whether repeated assessments in these contexts are capable of capturing change.

Tasks for assessing emotional attunement in the caregiver-adolescent relationship may also provide important indicators of attachment change. Emotionally attuned communication is a complex and multi-dimensional construct that must account for the degree to which both caregiver and adolescent contribute to maintaining open communication and a cooperative partnership. Deviations from emotionally attuned communication include negative reciprocity in caregiver-adolescent exchanges, role confused behaviors in which the adolescent organizes the interaction with the caregiver, or adolescent disengagement and withdrawal (Obsuth et al., 2013). These deviations from the secure cycle often co-occur with adolescent symptoms and problem behaviors, and pre-post reductions in these negative exchanges would provide an indicator of treatment efficacy. In addition to widely used conflict tasks, therapists may attend to other aspects of interaction, including the extent to which caregivers support the adolescent’s capacity to develop their goals and plans for the future, as well the degree to which dyads maintain positive interactions or “delight” in being with each other (Powell et al., 2013; Stern, 1985).

If measurable change occurs in proximal targets of an intervention, such as expectancies, emotion regulation, reflective function or emotional communication, questions follow about the degree to which change in one component of the IWMs or communication generalizes to other components in the secure cycle. For instance, if adolescents show improved emotion regulation that allows them to narrate attachment injuries, do these changes in emotion regulation carry forward into how the adolescent communicates with the caregiver? Similarly, if caregivers develop an increased ability to recognize and appropriately respond to adolescents’ attachment and autonomy needs, does this alter how they respond to adolescent problem behaviors? Does developing a reflective stance toward self and others necessarily result in more positive expectancies or more attuned communication? These questions go to the heart of what it may mean to revise or update an IWM or increase security in the caregiver-adolescent attachment bond. While interventions may target a specific component of IWMs, change is only likely to be consolidated if it is generalized to expectancies, emotion regulation, and communication.

ABTs are generally conceived as transdiagnostic treatments that may be useful in addressing a variety of adolescent symptoms and problem behaviors. However, the relation between attachment difficulties and adolescent psychopathology is most likely bidirectional. In some cases, attachment difficulties may clearly precede the development of symptoms. In other cases, adolescent problem behaviors may precipitate or exacerbate problems in the caregiver-adolescent attachment bond. An important challenge for future research is to link change in IWMs or caregiver-adolescent communication to symptom reduction. This will require comparing ABTs to other evidence-based treatments using symptom measures as a primary outcome. In order to demonstrate that improvement in attachment is the mechanism of change, ABTs must demonstrate that change in IWMs or communication precedes symptom reduction (Kazdin, 2007). Finally, assuming ABTs prove effective in reducing symptoms, the relative cost effectiveness and amenability to dissemination of these treatments could be compared to other evidence-based treatments.

Summary

ABTs for adolescents represent an important extension of attachment theory and research to the challenges of helping troubled adolescents and their caregivers. Incorporating adolescent treatments into this growing literature provides an opportunity to step back and clarify the defining features of ABTs and to think systematically about how to specify and measure the process of change in treatments that claim to be attachment-based. We have suggested that ABTs share the prototype of the secure cycle as a guide to assessing troubled families and we have reviewed ABT interventions that have been used to revise IWMs or improve emotional communication. This general framework can serve as a guide to further treatment development and evaluation. However, in order for ABTs to establish themselves in the world of evidence-based treatments, attachment researchers must develop measures of IWMs and emotionally attuned communication that are sensitive to therapeutic change. This effort is most likely to be successful when existing measures of IWMs and communication are adapted in active collaboration with treatment developers.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by NIMH grant RO1-MH91059. We are grateful to Guy Diamond, Ph.D and Suzanne Levy, Ph.D. and others at the Center for Family Intervention Science for case presentations and conversations that provided a stimulating clinical context for testing some of the concepts in this paper.

References

- Berking M, Wupperman P, Reichardt A, Pejic T, Dippel A, Znoj H. Behaviour Research and Therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46(11):1230–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin L. In: Handbook of Attachment. 2. Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K, Dozier M, Bick J, Lewis Morrarty E, Lindhiem O, Carlson E. Enhancing Attachment Organization Among Maltreated Children: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. Child Development. 2012;83(2):623–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K, Meade EB, Dozier M. Parental synchrony and nurturance as targets in an attachment based intervention: building upon Mary Ainsworth’s insights about mother–infant interaction. Attachment & Human Development. 2013;15(5–6):507–523. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2013.820920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss: Separation: anxiety and anger. London: Tavistock; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A Secure Base. New York: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Epilogue. In: Parkes CM, Stevenson-Hinde J, Marris P, editors. Attachment Across the Life Cycle. London: Routledge/Tavistock; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I. Revisiting Mary Ainsworth’s conceptualization and assessments of maternal sensitivity-insensitivity. 2013 doi: 10.1080/14616734.2013.835128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey TA. Exposure and reorganization: The what and how of effective psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(2):236–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R, Gullone E, Allen NB. Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(6):560–572. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond GS, Wintersteen MB, Brown GK, Diamond GM, Gallop R, Shelef K, Levy S. Attachment-Based Family Therapy for Adolescents with Suicidal Ideation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(2):122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon P, Target M, Sargent J, Williams LL, McGregor J, Bleiberg E, Fonagy P. Short-term mentalization and relational therapy (SMART): an integrative family therapy for children and adolescents. In: Allen JG, Fonagy P, editors. Practice in Handbook of Mentalization-Based Treatment. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. pp. 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Steele M, Steele H. The capacity for understanding mental states: The reflective self in parent and child and its significance for security of attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1991;12:201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Fraiberg S. Clinical studies in infant mental health. London: Tavistock; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg LS, Auszra L, Herrmann IR. The relationship among emotional productivity, emotional arousal and outcome in experiential therapy of depression. Psychotherapy Research. 2007;17(4):482–493. doi: 10.1080/10503300600977800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grice P. Studies in the Way of Words. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Haydon KC, Roisman GI, MJ An empirically derived approach to the latent structure of the Adult Attachment Interview: Additional convergent and discriminant validity evidence. Attachment & Human Development. 2011 doi: 10.1080/14616734.2011.602253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse E. The Adult Attachment Interview: Protocol, method of analysis, and empirical studies. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of Attachment. 2. Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman KT, Marvin RS, Cooper G, Powell B. Changing toddlers“ and preschoolers” attachment classifications: The circle of security intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(6):1017–1026. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes J. The Search for the Secure Base. London: Psychology Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM, Makinen JA, Millikin JW. Attachment injuries in couple relationships: A new perspective on impasses in couples therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2001;27(2):145–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2001.tb01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Mediators and Mechanisms of Change in Psychotherapy Research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3(1):1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keaveny E, Midgley N, Asen E, Bevington D, Fearon P. Minding the Family Mind: The development and initial evaluation of Mentalization Based Treatment for Families. In: Midgley N, Vrouva I, editors. Minding the Child: Mentalization-based interventions with children, young people and their families. London: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak R, Zajac K. Revaluating Adolescent States of Mind and Their Implications for Psychopathology: A Relational/Lifespan Framework. In: Cicchetti D, Roisman G, editors. The Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology, The Origins of Adaptation and Maladaptation. Vol. 36. New York: Erlbaum; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak R, Rosenthal NL, Zajac K, Madsen SD. Adolescent attachment hierarchies and the search for an adult pair-bond. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2007;2007(117):57–72. doi: 10.1002/cd.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak R, Duemmler S. Attachment and conversation: A discourse analysis of goal-corrected partnerships. In: Perlman D, Bartholomew K, editors. Advances in the Study of Personal Relationships. Vol. 5. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1994. pp. 121–149. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Cole HE, Ferenz-Gillies R, Fleming WS, Gamble W. Attachment and emotion regulation during mother-teen problem solving: a control theory analysis. Child Development. 1993;64(1):231–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kross E, Ayduk O. Making Meaning out of Negative Experiences by Self-Distancing. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2011;20(3):187–191. doi: 10.1177/0963721411408883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kross E, Ayduk O, Mischel W. When Asking “Why” Does Not Hurt Distinguishing Rumination From Reflective Processing of Negative Emotions. Psychological Science. 2005;16(9):709–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Goldwyn R. Adult attachment classification system. University of California; Berkeley: 1998. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Main M. Metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive monitoring. and singular (coherent) vs. multiple (incoherent) model of attachment: findings and directions for future research. In: Parkes CM, Stevenson-Hinde J, Marris P, editors. Attachment Across the Life Cycle. Vol. 2006. London: Routledge; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Weston DR. The quality of the toddler's relationship to mother and father: Related to conflict behavior and the readiness to establish new relationships. Child Development. 1981;52:932–940. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security in Infancy, Childhood, and Adulthood: A Move to the Level of Representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1985;50(1/2):66–104. doi: 10.2307/3333827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin R, Cooper G, Hoffman K, Powell B. The Circle of Security project: Attachment-based intervention with caregiver-pre-school child dyads. Attachment & Human Development. 2002;4(1):107–124. doi: 10.1080/14616730252982491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miccuci J. The Adolescent in Family Therapy: Harnessing the Power of Relationships. New York: Guilford; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, Sapir-Lavid Y, Avihou-Kanza N. What’s inside the minds of securely and insecurely attached people? The secure-base script and its associations with attachment-style dimensions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97(4):615–633. doi: 10.1037/a0015649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran G, Diamond G, Diamond G. The relational reframe and parents’ problem constructions in attachment-based family therapy. Psychotherapy Research. 2005;15(3):226–235. doi: 10.1080/10503300512331387780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti M, Obsuth I. Effectiveness of an attachment-focused manualized intervention for parents of teens at risk for aggressive behaviour: The Connect Program. Journal of Adolescence. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols MP. Family Therapy: Concepts and Methods. 10. New York: Pearson; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Obsuth I, Hennighausen K, Brumariu LE, Lyons-Ruth K. Disorganized Behavior in Adolescent-Parent Interaction: Relations to Attachment State of Mind, Partner Abuse, and Psychopathology. Child Development. 2013 doi: 10.1111/cdev.12113. n/a–n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim D, Koren-Karie N. The insightfulness assessment: measuring the internal processes underlying maternal sensitivity. Attachment & Human Development. 2013;15(5–6):545–561. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2013.820901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell B, Cooper G, Hoffman K, Marvin B. The Circle of Security Intervention. Guilford Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Fraley RC, Belsky J. A taxometric study of the Adult Attachment Interview. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43(3):675–686. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran J, Segal Z. Interpersonal Process in Cognitive Therapy. New York: Basic; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Salemink E, Wiers RW. Modifying Threat-related Interpretive Bias in Adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39(7):967–976. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9523-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvini MP, Boscolo L, Cecchin G, Prata G. Hypothesizing - Circularity - Neutrality: Three Guidelines for the Conductor of the Session. Family Process. 1980;19(1):3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1980.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C, Fonagy P. The Parent's Capacity to Treat the Child as a Psychological Agent: Constructs, Measures and Implications for Developmental Psychopathology. Social Development. 2008;17(3):737–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00457.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Adolescents, Families, and Social Development. John Wiley & Sons; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stern DN. The Interpersonal World of the Infant. Karnac Books; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Gravener-Davis JA, Guild DJ, Cicchetti D. Relational interventions for child maltreatment: past, present, and future perspectives. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25(4 Pt 2):1601–1617. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zeijl J, Mesman J, van Ijzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Juffer F, Stolk MN, et al. Attachment-based intervention for enhancing sensitive discipline in mothers of 1- to 3-year-old children at risk for externalizing behavior problems: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(6):994–1005. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallin DJ. Attachment in Psychotherapy. Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Waters TEA, Brockmeyer SL, Crowell JA. AAI coherence predicts caregiving and care seeking behavior: Secure base script knowledge helps explain why. 2013;15(3):316–331. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2013.782657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]