Abstract

Breast cancer (BrCa) is the leading cause of cancer related death in women. While current diagnostic modalities provide opportunities for early medical intervention, significant proportions of breast tumours escape treatment and metastasize. Gaining increasing recognition as a factor in tumour metastasis is the local immuno-surveillance environment. Following identification of the role played by the enzyme indoleamine dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) in mediating maternal foetal tolerance, the kynurenine pathway (KP) of tryptophan metabolism has emerged as a key metabolic pathway contributing to immune escape. In inflammatory conditions activation of the KP leads to the production of several immune-modulating metabolites including kynurenine, kynurenic acid, 3-hydroxykynurenine, anthranilic acid, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid, picolinic acid and quinolinic acid. KP over-activation was first described in BrCa patients in the early 1960s. More evidence has since emerged to suggest that the IDO1 is elevated in advanced BrCa patients and is associated with poor prognosis. Further, IDO1 positive breast tumours have a positive correlation with the density of immune suppressive Foxp3+ T regulatory cells and lymph node metastasis. The analysis of clinical microarray data in invasive BrCa compared to normal tissue showed, using two microarray databank (cBioportal and TCGA), that 86.3% and 91.4% BrCa patients have altered KP enzyme expression respectively. Collectively, these data highlight the key roles played by KP activation in BrCa, particularly in basal BrCa subtypes where expression of most KP enzymes was altered. Accordingly, the use of KP enzyme inhibitors in addition to standard chemotherapy regimens may present a viable therapeutic approach.

Keywords: breast cancer, kynurenine pathway, immune-evasion

BREAST CANCER

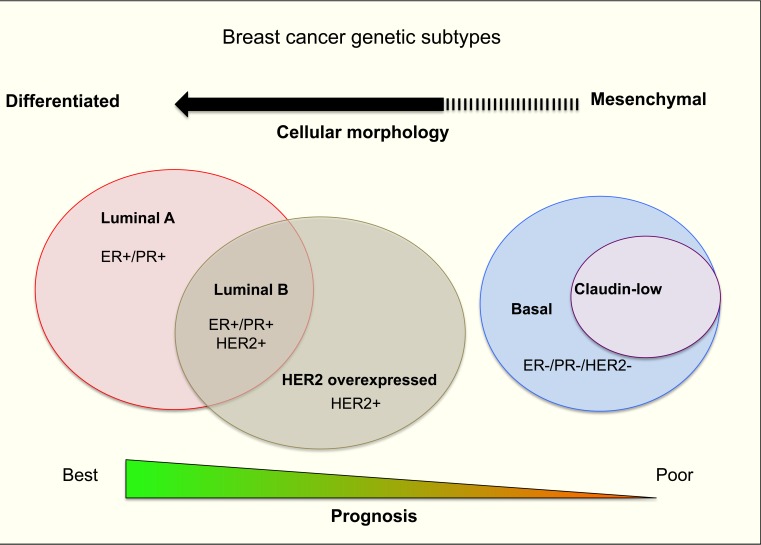

Breast cancer (BrCa) accounted for 11.9% of total worldwide cancer deaths in 2012 [1] despite recent advances in treatment and surveillance. BrCa is a heterogenic disease that can be categorized into four main molecular distinct subtypes based on gene expression profiling: luminal A, luminal B, human epithelial growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2) overexpressing and basal/triple negative (TN) cancer subtype [2-5] (Figure 1). A slight majority of diagnosed BrCa cases are luminal A subtype [2, 4] distinguished by high oestrogen receptor (ER) and/or progesterone receptor (PR) expression, but with a low expression of the cell proliferation marker Ki-67 [2, 4].

Figure 1. A summary of human breast cancer subtypes.

BRCA SUBTYPE MOLECULAR SIGNATURES AND ITS PROGNOSIS

Patients diagnosed with luminal A subtype have the best prognosis as this subtype is responsive to Tamoxifen hormone therapy [6]. The luminal B subtype also expresses ER and/or PR. However, as expression of the proliferation factor Ki-67 is higher than in the luminal A subtype, this subtype presents a higher risk of disease relapse [7]. HER-2 overexpressing subtype [2, 4], typically had a poor prognosis but the emergence of monoclonal antibody based therapies such as Trastuzumab, targeting the HER-2 receptor, has improved patient prognosis (44% reduction in risk of death) [8]. The basal/TN breast cancer subtype [2, 4] has the highest level of proliferation-related gene expression and frequencies of genetic mutations, such as TP53 and BRCA 1 [9]. Due to the lack of targeted treatments, the basal/TN subtype has the worst prognosis. Recently, a newly established breast cancer TN subtype, claudin-low, was described [2, 4] and was shown to lack epithelial cell-cell adhesion proteins such as E-cadherin and claudin 3, 4 and 7 [10]. Claudin-low tumours are also characterized by low luminal, high epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition features and by enhanced tumour initiating processes [11]. These properties render this subtype resistant to chemotherapy and hence these cells often dominate post-treatment tumour samples after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy or hormone therapy [12]. Patients diagnosed with this subtype also have a generally poor survival outcome [7]. Generally, each of the major subtypes comprises a roughly equal proportion of total breast cancer cases (11-23%).

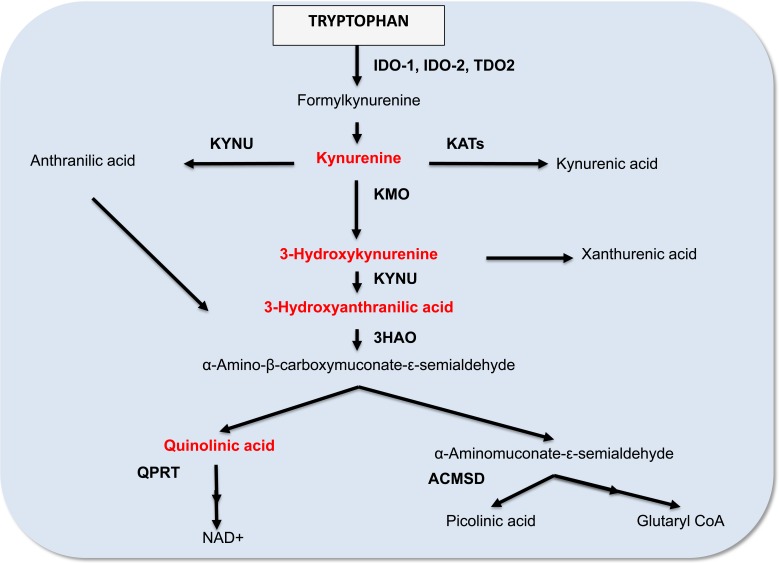

The molecular classification of breast tumour subtype has provided new opportunities to develop more appropriately targeted therapy. However, drug-based interventions will continue to be important for BrCa therapy. Another significant aspect to consider is the relationship between breast tumour development and immune tolerance. A particularly interesting recent development has been the discovery of the role of IDO1 in mediating tumour immune-evasion [13]. Specifically, alterations in tryptophan catabolism in both tumour and tumour-draining lymph nodes may provide a mechanistic avenue enabling tumour-cell persistence, a view that is supported by experimental evidence [14-16]. This review will focus on the contribution that alterations in tryptophan catabolism via the kynurenine pathway (KP; Figure 2) may play in BrCa progression. Understanding how BrCa cells exploit such immune evasion mechanisms may lead to identifying promising therapeutic targets for BrCa and metastasis based on modulation of tryptophan metabolism.

Figure 2. A simplified diagram of the kynurenine pathway.

TRYPTOPHAN METABOLISM: FOCUS ON THE KYNURENINE PATHWAY

Tryptophan is an essential amino acid obtained through the diet [17]. Under physiological conditions, the majority of tryptophan is catabolized through the KP to synthesize the vital energy cofactor, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) [18]. Several downstream metabolites of the KP are biologically active in various physiological and pathological processes, including kynurenine (KYN), kynurenic acid, 3-hydroxykynurenine, anthranilic acid, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (3-HAA), picolinic acid and quinolinic acid (QUIN).

Three different heme-enzymes, indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) [19], indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase 2 (IDO2) [20, 21] and tryptophan 2,3 dioxygenase (TDO2) [22], catalyse the first rate-limiting key step of the KP. Despite sharing the same substrate, the two IDO isoforms and TDO2 each have distinct inducers and patterns of tissue expression. IDO1 is highly induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ [23] whereas TDO-2 is induced by its substrate tryptophan and by glucocorticoids [24]. Induction of IDO2, however, is less well understood. IDO1 is commonly expressed in all major organs and immune T and B cells [25], whereas IDO2 is expressed by hepatocytes, in the bile duct, neuronal cells of the cerebral cortex and dendritic cells [26]. TDO-2 is primarily expressed in the liver [27], but is also expressed in placenta [28], maternal and embryonic tissues [29], and brain [30].

A key juncture of the KP leads to the catabolism of 2-amino-3-carboxymuconate semialdehyde (ACMS) to 2-aminomuconic acid 6-semialdehyde (AMAS) by 2-amino-3-carboxymuconate semialdehyde decarboxylase (ACMSD), then AMAS non-enzymatically converts to the neuroprotective metabolite picolinic acid (Figure 2) [31]. Alternatively, the KP can branch towards the non-enzymatic rearrangement of ACMS to form the metabolite QUIN, an essential precursor for de novo NAD+ synthesis. Under normal physiological conditions, the production of picolinic acid and QUIN is at equilibrium [32]. However, during chronic activation KP metabolism is diverted towards QUIN production, and hence NAD+ biosynthesis, which may promote cellular growth.

KP-MEDIATED IMMUNE-MODULATION IN CANCER

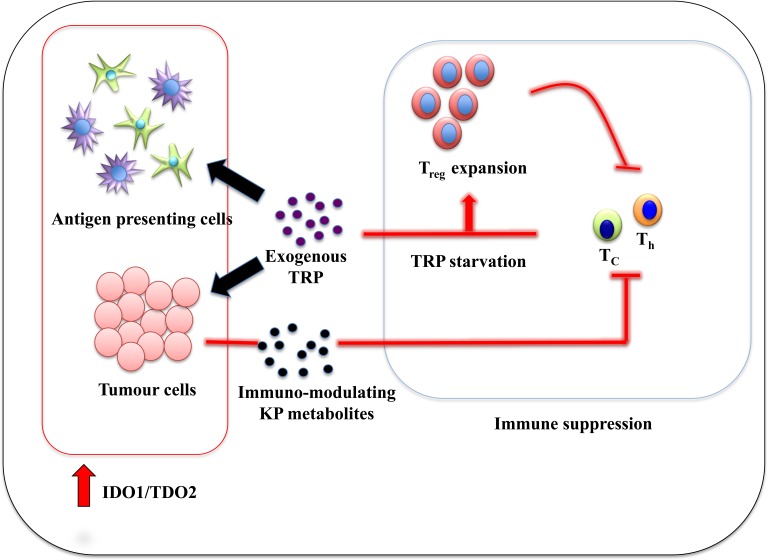

Since the demonstration that IDO1 has immuno-suppressive ability by mediating maternofetal tolerance [33], much attention has been dedicated to determining how IDO1 also modulates the immune response to tumours. In most forms of human cancers, including BrCa, high IDO1 expression is positively correlated to poor prognosis [34-41]. Studies utilizing murine cancer models confirmed that IDO1/TDO2 over-expressing tumours are more aggressive compared to tumours with basal IDO1/TDO2 levels [15, 16, 42]. In this paradigm, the generally pro-inflammatory cancer microenvironment leads to IDO1/TDO2 over-expression in stoma (epithelial and endothelial cells) and/or antigen-presenting cells (APCs) such as dendritic cells (DC) [43] resulting in depletion of tryptophan in the local milieu. Hence, local cytotoxic T-cells (Tc) and T helper cells (Th) become tryptophan deficient leading to inhibition of proliferation as a result of general control nonderepressible 2 (GCN2) signalling pathway activation [44, 45]. Tryptophan starvation also predisposes activated T-cells to Fas-dependent apoptosis [44, 45]. Consequently, CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) mature to become the prominent T-cells population in the microenvironment [46-48]. These T-cell subset populations have a potent suppressive effect on both innate and adaptive immunity [49, 50]. Not only do Tregs impose immuno-tolerance on the microenvironment, but they also promote immuno-tolerance in draining lymph nodes, thereby potentiating the likelihood of distant metastasis, a phenomenon that has been observed in several cancer types and is a significant ongoing problem in BrCa (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Immune tolerance mechanism by IDO1:TDO2 overexpression in cancer-associated inflammation environment.

In vivo studies using various animal models of human cancers treated with IDO inhibitors have provided relevant proof-of-concept that tryptophan metabolism is involved in tumour immune-escape. Two initial studies by Uyttenhove et al. [16] and Friberg et al. [51] demonstrated that the IDO inhibitor 1-methyltryptophan (1-MT), limited the growth of IDO1 overexpressing tumours engrafted in a syngeneic host. Further studies by Muller et al. [42] confirmed that 1-MT modestly slowed the growth of spontaneous mammary tumours in MMTV/neu mice. When combined with the cancer chemotherapeutic drug paclitaxel, MMTV/neu tumour size regressed by 30% with no side effects observed [42]. This suggested that 1-MT has only limited efficacy as a monotherapy, but is effective in combination together with chemotherapy. Additionally, immunodepletion of CD4+ or CD8+ T-cells before treatment abolished the efficacy of 1-MT treatment, suggesting that the anti-tumoral efficacy of 1-MT is dependent on a specific T-lymphocyte response.

While the majority of studies support the tumour-promoting activity of IDO1, it is important to note that other studies suggest that IDO1 may have anti-tumour activity [52]. These studies demonstrated that IFN-γ induced IDO1 resulted in depletion of the essential metabolite tryptophan, presumably reducing NAD+ production within the tumour cell thereby limiting cell growth. Animal studies have shown that IFN-γ induced IDO1 restricted tumour growth [53, 54] and while clinical studies have shown that hepatocellular and renal cell carcinoma specimens evidenced a positive association between IDO1 expression and favourable outcomes [55, 56]. However, both clinical studies noted that IDO1 expression was restricted to tumour infiltrating cells but was not found in the tumour cells. This potentially highlights the different roles (pro- and anti-tumorigenic) of elevated IDO1 expression within tumour cells as well as its microenvironment.

KP METABOLITES: INVOLVEMENT IN CANCER IMMUNOBIOLOGY

KYN

KYN is the first catabolite produced from tryptophan by IDO1/2 and/or TDO2. KYN has been recently identified as an endogenous ligand for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) [57], a key ligand-activated transcription factor involved in diverse cellular functions such as cellular differentiation and proliferation. Activation of the AhR by KYN promotes selective expansion of Tregs due to activation of forkhead box p3 (Foxp3) in naïve T-cells preventing maturation of Th17 cells [58]. Martin-Orozco and colleagues subsequently showed that depletion of the Th17 population favoured tumour growth in the lungs of mice injected intravenously with B16-F10 melanoma [59]. Adaptive transfer of antigen-challenged Th17 into tumour-bearing mice led to a lower rate of tumour establishment and growth whereas Th17 free mice could not prevent establishment of tumour allografts. The distinct anti-tumour effect of the Th17 cell subset reflects an ability to enhance DC infiltration and Tc cells immune response [59]. Accordingly, active expansion of Tregs cells through KYN-AhR activation creates an immune suppressive zone around IDO1 and/or TDO2 expressing tumours.

Enhanced tumour-cell survival and motility also results from KYN-AhR activation. Opitz et al., found that TDO2 expressing (i.e. KYN producing) brain tumour xenografts in AhR-proficient mice had an enhanced tumour growth rate, increased levels of the inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8) and a decreased number of infiltrating CD8+ cells around tumours with high AhR and TDO2 expression [57]. The persistence of elevated inflammatory cytokines in the microenvironment may lead to chronic IDO1 expression in APC cells such as macrophages and DC and/or tumour cells [60] thereby creating a pro-inflammatory feedback loop promoting tumour growth. Collectively, these studies highlight the importance of the AhR in IDO1 and/or TDO2 expressing tumours and emphasize the role that autocrine production of inflammatory cytokines plays in tumour survival and growth. Whether similar tumour-promoting interactions occur with KYN and AhR in BrCa remains unknown but are likely.

3-HAA

Among the KP metabolites, 3-HAA appears to have the highest capacity to modulate the immune functions of both monocytic cells and lymphocytes. Macrophages treated with 3-HAA, lose their ability to synthesize nitric oxide (NO), due to upstream inhibition of both NF-κB and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) activity [61]. Considering that NO production by macrophages is critical to their immune-mediator function, inhibition of NO synthesis may impair macrophage ability to eradicate tumour cells.

Induction of kinase 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 [62], caspsase-8 and cytochrome c [63] by 3-HAA also induces apoptosis in both Tc and Th1 populations of effector T cell [64]. Additionally, 3-HAA also limits cytokine-stimulated Tc proliferation by reducing the number of T-cells entering the cell cycle [65]. The reduction of these two major effector T-cell populations may impair the immune response against KP expressing tumours. More recently, 3-HAA has also been shown to specifically enhance the differentiation of Tregs. A 70% increase in the number of Tregs cells is observed after the treatment of naïve T cells with a KP metabolite cocktail containing 10 μM of 3-HAA [63, 64]. This result was further confirmed by both Favre et al. and Zaher et al. who also reported strong Tregs differentiation in the presence of 3-HAA [66, 67]. In summary, chronic production of 3-HAA by cancer cells may not only lead to progressive loss of competent immune cells but also expansion of immune suppressive cells, dampening immune surveillance and thereby encouraging tumour growth.

Picolinic acid

Picolinic acid is one of the alternate end products of the KP, resulting from the enzymatic conversion of ACMS by the enzyme ACMSD (Figure 2). Picolinic acid is an endogenous metal chelator for elements such as iron [68]. Based on its iron chelation properties and the fact that other iron chelators such as desferrioxamine exhibit anti-tumour activity, picolinic acid has also been assessed for its anti-tumour activity [69]. Indeed, picolinic acid challenged tumour cells have decreased proliferation rates in vitro [70, 71] and in vivo [72], as compared to untreated control cells. Normal human cells, however, remain unaffected at the same dosage [73].

Picolinic acid is also associated with immune function. Picolinic acid interacts synergistically with IFN-γ to augment iNOS production by macrophages [74-76], increasing iNOS mRNA expression by 10 to 15 fold leading to a potent cytotoxic/cytostatic effect. This synergistic interaction was found to last for at least 20 hours. Picolinic acid challenged macrophages have been shown to inhibit tumour growth and increase survival in cancer animal models [76-78]. In addition to macrophage activation, picolinic acid also potently induces macrophage production of the chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α and -1β which also contributes to tumour eradication [79].

QUIN

Under normal physiological conditions, QUIN is the precursor for the production of the essential co-factor NAD+. This reaction is catalysed by the QPRT (Figure 2). QUIN is an agonist of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor and in pathophysiological conditions excess QUIN can induce over-activation of the NMDA receptor leading to excitotoxicity in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease [80]. Quin is also known to be involved in tumour neuropathogenesis and persistence [81-83]. When treated in vitro, Quin increased the proliferation rate of human glioblastoma U343MG cells [84], HT-116 and HT-29 colon cancer cells [85] and SK-N-SH neuroblastoma [71]. Interestingly, QUIN also increases astroglial production of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor [86], which may induce proliferation of cancer cells and increase resistance to chemotherapeutic agents [87]

We showed that QPRT is strongly elevated in higher grade gliomas leading to increased QUIN production, which was significantly associated with poor prognosis [88]. High QUIN levels promote tumour chemo-resistance due to enhanced production of NAD+, a vital substrate for Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase-1 (PARP-1) activation [89], which facilitates repair of reactive oxygen species-induced DNA damage and enables cells to recover DNA replication after treatment [90]. In fact, QUIN treated malignant human glioma cells were less sensitive to temozolomide and H2O2 mediated apoptosis compared to untreated glioma cells [88]. Similarly to 3-HAA, QUIN also modulates the immune response through selective inhibition of Th and Tc proliferation and natural killer cell activation [64]. QUIN expression can also increase Tregs population [67]. These results show that excessive QUIN in the tumour microenvironment may have a significantly detrimental effect on local immuno-surveillance. However, the precise role that QUIN may play in BrCa remains to be elucidated.

Kynurenic acid

Kynurenic acid can antagonize QUIN excitotoxicity at NMDA receptors and hence functions as an endogenous neuroprotectant. Whereas 3-HAA and QUIN have immunosuppressive properties that are likely to promote tumour growth [81], kynurenic acid can inhibit adenocarcinoma and renal cell carcinoma cancer cell proliferation in vitro [91]. Inhibition of the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway proteins is one of the possible anti-tumour activities of kynurenic acid [91]. The MAPK pathway promotes several cellular processes including motility, proliferation and survival [92] and is frequently over-activated in human cancer [93, 94]. Kynurenic acid is also known to up-regulate the expression of p21 Waf1/Cip that induces cell-cycle arrest [95]. Hence the presence of kynurenic acid in the tumour microenvironment might help to limit tumour growth.

REDOX MODULATION BY KP METABOLITES: POTENTIAL INVOLVEMENT IN CANCER GROWTH

Under certain intracellular or microenvironment conditions KP metabolites have been shown to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as H2O2 and hydroxyl radical. Formation of ROS has been linked to cancer initiation and progression by inducing lipid peroxidation, DNA damage/mutation and cell proliferation [96]. Indeed, one of the most extensively studied LP products are the 4-hydroxy-2-nonenals (4-HNE) which modulate a number of signaling processes such as Akt pathway involved in cancer initiation and progression [97]

In the presence of transition metals such as copper (Cu2+), manganese (Mn2+) and iron (Fe3+), 3-hydroxykynurenine and 3HAA can be oxidized to generate ROS [98] which is a well-known cause of DNA damage [99]. More recently, it was suggested that 3-hydroxykynurenine mediated cell death independently of caspase-3 activation via p38 MAPK phosphorylation [100]. 3HAA-generated ROS was shown to enhance apoptosis in precursor immune cells such as thymocytes [101] and monocytes [102]. Furthermore, 3HAA can auto-oxidize and generate cinnabarinic acid, which induces apoptosis in thymocytes by an order of magnitude greater than 3HAA [101]. Redox-mediated depletion of these precursor immune cells by 3HAA could lead to tumor persistence due to reduced numbers of mature T-cells. Despite much research supporting a pro-oxidant effect, 3-hydroxylkynurenine and 3HAA also have documented antioxidant properties [103-105]. In fact, 3-hydroxykynurenine and 3HAA has been shown to protect the brain and gliomas against oxidative stress by inhibiting spontaneous lipid peroxidation [106, 107].

QUIN is another KP metabolite that enhances ROS formation in the tumour microenvironment by several mechanisms including formation of redox-active complexes with Fe2+ leading to lipid peroxidation [108]. However, QUIN was also observed to act as an anti-oxidant in electrochemical studies. Low concentrations of QUIN reduced the rate of ROS production by affecting the Fe2+/Fe3+ ratios, only at concentrations above pathophysiological levels were pro—oxidant effects observed [109].

These somewhat conflicting observations suggest that the specific environmental milieu may determine the net ROS balance of these metabolites, which is not yet precisely defined in cancer.

EVIDENCE FROM CLINICAL STUDIES

Up-regulation of KP metabolism in BrCa patients was first reported by Rose et al (1967) who found increased kynureninase (KYNU), kynurenine-3-monooxygenase (KMO), and kynurenine aminotransferase-II enzyme activity (Figure 2) in the urine of untreated BrCa patients compared to controls [110]. While one-third of the patient cohort exhibited higher activity of these three enzymes, the remaining patients had similar enzymatic profiles to the control group. A potential explanation may be that the KP is differently modulated in the different BrCa subtypes. A later study by Sakurai et al. also detected higher IDO1 activity in the serum of BrCa patients and higher IDO1 mRNA expression in BrCa compared to normal tissue [111]. The elevated serum levels and IDO1 expression in tumour correlates to clinical stage, in agreement with another study by Rose et al. showing elevated KP enzyme activity in approximately one third of early cancer patients and in half of advanced BrCa patients respectively [112]. However, increased KP activity in advanced-stage patients was only evident in those with soft tissue metastases. Patients with skeletal metastases displayed normal KP activity, suggesting that KP over-activation may drive proximal tissue invasion but not distal metastasis. There is also evidence of immune system suppression in IDO1-positive advanced BrCa patients as IDO1 expressing breast tumours had higher numbers of infiltrating Tregs in tumour and lymph node metastases [113-115].

A later prospective cohort study showed that KP metabolism returned to near normal levels in BrCa patients post-mastectomy, with- or without-oophorectomy, further demonstrating the link between tumour presence and KP modulation [116]. More recently, post-surgical re-normalization of KP metabolism in BrCa patients was confirmed together with reduced IDO1 activity expression post-chemotherapy [117].

Despite much evidence that IDO1 expression is associated with poor prognosis in BrCa patients, a study of medullary BrCa patients showed that high IDO1 expression was associated with favourable outcomes [118]. This study agrees with others [55, 56] where IDO1 expression was observed in the surrounding dendritic-like monocytes rather than the tumour cells. This again raises the possibility that IDO1 locality determines whether it supports or prevents tumour growth.

Evidence from microarray databank

Data mining from ex vivo clinical studies

An early collective and global BrCa study in cBioportal using the Agilent microarray series showed that a total 86.3% of all BrCa cases had altered mRNA expression of enzymes in the KP (454 out of 526 BrCa patients, z-score of −1< and >1, Table 1A) [119, 120]. Data from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) confirmed the cBioprotal results and showed a slightly higher percentage of total 91.4% of patients with altered KP enzyme expression (169 of 185 patients, z-score of −1< and >1; Table 1A). However, as both databases did not differentiate BrCa subtype, it is not possible to draw firm conclusions regarding whether specific KP enzymes were up-or down-regulated. Furthermore, the heterogeneous database presentation may dilute subtype specific KP dysregulation evidence.

Table 1A. KP enzymes mRNA expression by microarray database.

| cBioPortal (n = 526) | TCGA (n = 185) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| %. of KP mRNA changes | % of elevated mRNA | %. of KP mRNA changes |

% of elevated mRNA | |

| IDO-1 | N.A. | N.A. | 32 | 53 |

| TDO2 | 33 | 53 | 34 | 51 |

| KMO | 35 | 61 | 36 | 52 |

| 3HAO | 22 | 49 | 21 | 53 |

| KYNU | 26 | 55 | 23 | 60 |

| ACMSD | 22 | 49 | 24 | 80 |

| QPRT | 36 | 54 | 37 | 49 |

However, microarray data from patients with invasive breast carcinoma (cBioPortal; PAM50 series) [119, 120] (Table 1B, z score <-1 and >1) overcame this limitation. This data showed that the mRNA expression of specific KP enzymes differed substantially by BrCa subtype. Significantly, the claudin low subtype, exhibited elevated TDO2 and KYNU mRNA expression in more than half of the samples; while a quarter of the samples exhibited elevated KMO and 3-hydroxyanthranilate 3,4-dioxygenase (3HAO). In the similarly aggressive basal BrCa subtype, both TDO2 and KYNU were also elevated. Elevated expression of TDO2 is indicative of active breakdown of tryptophan leading to increased production of the potent immuno-suppressive metabolite 3-HAA. Intriguingly, ACMSD remained unchanged or down-regulated in these subtypes suggesting a KP pathway shift towards quinolinic acid and energy production (thereby facilitating tumour progression) and away from production of the tumour suppressive metabolite picolinic acid. In the HER2-overexpressing BrCa subtype, TDO2, KMO, KYNU and QPRT were elevated similarly to both the claudin-low and basal subtypes in 34% to 59% of total specimens. Considering that these subtypes are associated with higher rates of lymph node metastasis, elevation of the early KP enzymes TDO2, KMO and KYNU may promote tumour aggressiveness and metastasis. Interestingly, a portion of HER2 over-expressing specimens had elevated ACMSD, suggesting increased production of anti-tumour picolinic acid metabolite. This is a potentially contradictory observation in a subtype associated with poor prognosis, given the anti-tumour activity of picolinic acid (as described above) anti-tumorigenic property. However, a potential explanation of this anomaly may be that enhanced picolinic acid by tumour cells could be a potential strategy to chelate additional iron for growth, although there is no data to support this hypothesis.

Table 1B. KP enzymes mRNA expression by human breast cancer subtypes from PAM50 series/cBioPortal.

| Claudin low (n = 8) | Basal (n = 81) | HER2 (n = 58) |

Luminal A (n = 235) | Luminal B (n = 133) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA changes | Total changes (%) |

Elevated (%) |

Total changes (%) |

Elevated (%) |

Total changes (%) |

Elevated (%) |

Total changes (%) |

Elevated (%) |

Total changes (%) |

Elevated (%) |

| TDO2 | 63 | 100 | 34 | 79 | 41 | 92 | 29 | 25 | 34 | 56 |

| KMO | 25 | 100 | 12 | 60 | 59 | 100 | 36 | 57 | 35 | 49 |

| 3HAO | 25 | 100 | 22 | 67 | 19 | 82 | 21 | 55 | 26 | 17 |

| KYNU | 63 | 100 | 27 | 86 | 34 | 95 | 23 | 34 | 25 | 39 |

| ACMSD | 38 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 19 | 64 | 28 | 89 | 25 | 76 |

| QPRT | 13 | 100 | 31 | 56 | 55 | 94 | 31 | 31 | 35 | 66 |

In contrast, both the low-metastatic risk luminal A and B subtypes showed no changes in KP apart from elevated ACMSD mRNA, which as discussed, could lead to higher concentrations of picolinic acid and a more tumour suppressive KP profile.

Clinical data from the Genes-to-Systems Breast Cancer database [121] was then used to examine the relationship between breast tumour grade and KP mRNA expression profile. This analysis showed that TDO2 expression was higher in well, and moderately differentiated grade 1 and 2 breast tumours, compared to poorly differentiated grade 3 tumours. Increased KP enzymes mRNA expression in invasive breast carcinoma was also observed in the European Molecular Biology laboratory Gene Expression Atlas (EMBL; Table 1C) [122-125]. All invasive carcinoma samples examined in these studies had elevated IDO1, TDO2 and KMO. Interestingly, normal breast epithelial cells in the immediate tumour proximity also showed elevated TDO2 and KMO expression, implying that IDO1/TDO2 expressing tumours have the capability to influence KP activity in surrounding normal tissue. This not only highlights the potential interplay between these three KP enzymes in facilitating tumour invasion, but also suggests that targeting a single KP enzyme may not be optimal for complementary cancer immunotherapy. This agrees with our study demonstrating that the entire pathway is active in human brain tumours that suppresses the anti-tumour immune response and support tumour growth [57]. Collectively, these data suggest that the elevated KP activity contributes to tumour aggressiveness.

Table 1C. KP enzymes mRNA expression in human breast cancer specimens from EMBL-gene Atlas.

| Disease group | n value | KP enzymes expression | Array number | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDO-1 | TDO2 | KMO | ||||

| Normal breast | 143 | E-GEOD-10780 | 96 | |||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 42 | |||||

| Reduction mammoplastices | 10 | E-TABM-276 | 97 | |||

| Invasive ductual carcinoma | 23 | |||||

| 0 cm away from tumour | 28 | |||||

| 1 to 4 cm away from tumour | ||||||

| Normal breast | 15 | E-GEOD-8977 | 98 | |||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 7 | |||||

| Ductal carcinoma in situ | 53 | E-GEOD-41194 | 99 | |||

| Invasive breast cancer | 51 | |||||

*Black box: No change in mRNA expression; Green box: up regulation in mRNA expression

CONCLUSIONS

Since the discovery of the essential role played by IDO1 in mediating maternal foetal tolerance, a great deal of interest has focused on the roles that IDO1 and other KP enzymes may play in cancer immunology. Over the past decade strong evidence has accumulated that confirms that IDO1/TDO2 overexpression in tumour results in tryptophan depletion in the microenvironment, in turn, suppressing the T-cell mediated immune response. Other observations also implicate KP activation in promoting immune evasion. Higher 3-HAA concentrations, resulting from increased KYNU activity, causes reduced iNOS expression in macrophages, impairing their anti-tumour activity. Increased Tregs population caused by KYN-AhR activation further promotes immune suppression in the tumour vicinity and increases in QUIN, the NAD+ precursor, enhances cell proliferation. Considering these observations, there has been considerable interest in the potential of IDO1 inhibitors to reverse immune evasion with the majority of studies providing positive results.

Clinical data confirms the role of KP activation in BrCa and provides support for the use of KP enzyme inhibitor/s in addition to standard chemotherapy regimens. Significantly, KP activation seems to be associated with the more aggressive forms of BrCa that readily metastasize. Hence, it is possible to speculate that BrCa patient KP profiling may provide a valuable biomarker potentially capable of discriminating between non-invasive and invasive BrCa. Such methodology may have significant diagnostic, prognostic and/or therapeutic value.

Acknowledgments

Cure for life Foundation, Tour de Cure Foundation, The St Vincent Clinic Foundation, The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Australian Research Council (ARC) and The Curran Foundation (Australia) are thanked for supporting our work.

Abbreviations

- 1-MT

1-methyltryptophan

- 3-HAA

3-hydroxyanthranilic acid

- 3HAO

3-hydroxyanthranilate 3,4-dioxygenase

- ACMS

2-amino-3-carboxymuconate semialdehyde

- ACMSD

2-amino-3-carboxymuconate semialdehyde decarboxylase

- AhR

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- AMAS

2-aminomuconic acid 6-semialdehyde

- APCs

Antigen presenting cells

- BrCa

Breast cancer

- DC

Dendritic cells

- ER

Estrogen receptor

- Foxp3

forkhead box p3

- IDO1

Indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase 1

- IDO2

Indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase 2

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- KMO

Kynurenine-3-monooxygenase

- KP

Kynurenine pathway

- KYN

Kynurenine

- KYNU

Kynureninase

- MAPK

mitogen activated protein kinase

- NAD+

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- NMDA

N-methyl-d-aspartate

- NO

Nitric oxide

- QUIN

quinolinic acid

- PR

Progesterone receptor

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- Tc

Cytotoxic T-cells

- TDO2

Tryptophan 2,3 dioxygenase 2

- Th

T helper cells

- TN

Basal/triple negative

- Tregs

CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

BH, CKL and GJG conceptualized, drafted and written the manuscript. DBL, LG and AB participated during the draft and proof-read the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JW, Comber H, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. European journal of cancer. 2013;49:1374–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, Fluge O, Pergamenschikov A, Williams C, Zhu SX, Lonning PE, Borresen-Dale AL, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hergueta-Redondo M, Palacios J, Cano A, Moreno-Bueno G. “New” molecular taxonomy in breast cancer. Clinical & translational oncology. 2008;10:777–785. doi: 10.1007/s12094-008-0290-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, Hastie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Thorsen T, Quist H, Matese JC, Brown PO, Botstein D, Lonning PE, et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:10869–10874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sotiriou C, Pusztai L. Gene-expression signatures in breast cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360:790–800. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher B, Costantino J, Redmond C, Poisson R, Bowman D, Couture J, Dimitrov NV, Wolmark N, Wickerham DL, Fisher ER, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating tamoxifen in the treatment of patients with node-negative breast cancer who have estrogen-receptor-positive tumors. The New England journal of medicine. 1989;320:479–484. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198902233200802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van ‘t Veer LJ, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ, He YD, Hart AA, Mao M, Peterse HL, van der Kooy K, Marton MJ, Witteveen AT, Schreiber GJ, Kerkhoven RM, Roberts C, Linsley PS, Bernards R, Friend SH. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002;415:530–536. doi: 10.1038/415530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pegram MD, Konecny G, Slamon DJ. The molecular and cellular biology of HER2/neu gene amplification/overexpression and the clinical development of herceptin (trastuzumab) therapy for breast cancer. Cancer treatment and research. 2000;103:57–75. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-3147-7_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reis-Filho JS, Tutt AN. Triple negative tumours: a critical review. Histopathology. 2008;52:108–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prat A, Parker JS, Karginova O, Fan C, Livasy C, Herschkowitz JI, He X, Perou CM. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of the claudin-low intrinsic subtype of breast cancer. Breast cancer research. 2010;12:R68. doi: 10.1186/bcr2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creighton CJ, Li X, Landis M, Dixon JM, Neumeister VM, Sjolund A, Rimm DL, Wong H, Rodriguez A, Herschkowitz JI, Fan C, Zhang X, He X, Pavlick A, Gutierrez MC, Renshaw L, et al. Residual breast cancers after conventional therapy display mesenchymal as well as tumor-initiating features. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:13820–13825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905718106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hennessy BT, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Stemke-Hale K, Gilcrease MZ, Krishnamurthy S, Lee JS, Fridlyand J, Sahin A, Agarwal R, Joy C, Liu W, Stivers D, Baggerly K, Carey M, Lluch A, Monteagudo C, et al. Characterization of a naturally occurring breast cancer subset enriched in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and stem cell characteristics. Cancer research. 2009;69:4116–4124. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prendergast GC. Immune escape as a fundamental trait of cancer: focus on IDO. Oncogene. 2008;27:3889–3900. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz JB, Muller AJ, Prendergast GC. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in T-cell tolerance and tumoral immune escape. Immunological reviews. 2008;222:206–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pilotte L, Larrieu P, Stroobant V, Colau D, Dolusic E, Frederick R, De Plaen E, Uyttenhove C, Wouters J, Masereel B, Van den Eynde BJ. Reversal of tumoral immune resistance by inhibition of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:2497–2502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113873109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uyttenhove C, Pilotte L, Theate I, Stroobant V, Colau D, Parmentier N, Boon T, Van den Eynde BJ. Evidence for a tumoral immune resistance mechanism based on tryptophan degradation by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Nature medicine. 2003;9:1269–1274. doi: 10.1038/nm934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moffett JR, Namboodiri MA. Tryptophan and the immune response. Immunology and cell biology. 2003;81:247–265. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2003.t01-1-01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colabroy KL, Begley TP. Tryptophan catabolism: identification and characterization of a new degradative pathway. Journal of bacteriology. 2005;187:7866–7869. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.22.7866-7869.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takikawa O, Yoshida R, Kido R, Hayaishi O. Tryptophan degradation in mice initiated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1986;261:3648–3653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ball HJ, Sanchez-Perez A, Weiser S, Austin CJ, Astelbauer F, Miu J, McQuillan JA, Stocker R, Jermiin LS, Hunt NH. Characterization of an indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-like protein found in humans and mice. Gene. 2007;396:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ball HJ, Yuasa HJ, Austin CJ, Weiser S, Hunt NH. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-2; a new enzyme in the kynurenine pathway. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2009;41:467–471. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ren S, Liu H, Licad E, Correia MA. Expression of rat liver tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase in Escherichia coli: structural and functional characterization of the purified enzyme. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 1996;333:96–102. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takikawa O, Kuroiwa T, Yamazaki F, Kido R. Mechanism of interferon-gamma action. Characterization of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in cultured human cells induced by interferon-gamma and evaluation of the enzyme-mediated tryptophan degradation in its anticellular activity. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1988;263:2041–2048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren S, Correia MA. Heme: a regulator of rat hepatic tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase? Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2000;377:195–203. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braun D, Longman RS, Albert ML. A two-step induction of indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase (IDO) activity during dendritic-cell maturation. Blood. 2005;106:2375–2381. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-0979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukunaga M, Yamamoto Y, Kawasoe M, Arioka Y, Murakami Y, Hoshi M, Saito K. Studies on tissue and cellular distribution of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 2: the absence of IDO1 upregulates IDO2 expression in the epididymis. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry. 2012;60:854–860. doi: 10.1369/0022155412458926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knox WE, Mehler AH. The conversion of tryptophan to kynurenine in liver. I. The coupled tryptophan peroxidase-oxidase system forming formylkynurenine. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1950;187:419–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minatogawa Y, Suzuki S, Ando Y, Tone S, Takikawa O. Tryptophan pyrrole ring cleavage enzymes in placenta. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2003;527:425–434. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0135-0_50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki S, Tone S, Takikawa O, Kubo T, Kohno I, Minatogawa Y. Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase in early concepti. The Biochemical journal. 2001;355:425–429. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3550425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haber R, Bessette D, Hulihan-Giblin B, Durcan MJ, Goldman D. Identification of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase RNA in rodent brain. Journal of neurochemistry. 1993;60:1159–1162. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pucci L, Perozzi S, Cimadamore F, Orsomando G, Raffaelli N. Tissue expression and biochemical characterization of human 2-amino 3-carboxymuconate 6-semialdehyde decarboxylase, a key enzyme in tryptophan catabolism. The FEBS journal. 2007;274:827–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salter M, Knowles RG, Pogson CI. Quantification of the importance of individual steps in the control of aromatic amino acid metabolism. The Biochemical journal. 1986;234:635–647. doi: 10.1042/bj2340635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munn DH, Zhou M, Attwood JT, Bondarev I, Conway SJ, Marshall B, Brown C, Mellor AL. Prevention of allogeneic fetal rejection by tryptophan catabolism. Science. 1998;281:1191–1193. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5380.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Astigiano S, Morandi B, Costa R, Mastracci L, D'Agostino A, Ratto GB, Melioli G, Frumento G. Eosinophil granulocytes account for indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-mediated immune escape in human non-small cell lung cancer. Neoplasia. 2005;7:390–396. doi: 10.1593/neo.04658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brandacher G, Perathoner A, Ladurner R, Schneeberger S, Obrist P, Winkler C, Werner ER, Werner-Felmayer G, Weiss HG, Gobel G, Margreiter R, Konigsrainer A, Fuchs D, Amberger A. Prognostic value of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in colorectal cancer: effect on tumor-infiltrating T cells. Clinical cancer research. 2006;12:1144–1151. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chamuleau ME, van de Loosdrecht AA, Hess CJ, Janssen JJ, Zevenbergen A, Delwel R, Valk PJ, Lowenberg B, Ossenkoppele GJ. High INDO (indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase) mRNA level in blasts of acute myeloid leukemic patients predicts poor clinical outcome. Haematologica. 2008;93:1894–1898. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ino K, Yoshida N, Kajiyama H, Shibata K, Yamamoto E, Kidokoro K, Takahashi N, Terauchi M, Nawa A, Nomura S, Nagasaka T, Takikawa O, Kikkawa F. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase is a novel prognostic indicator for endometrial cancer. British journal of cancer. 2006;95:1555–1561. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okamoto A, Nikaido T, Ochiai K, Takakura S, Saito M, Aoki Y, Ishii N, Yanaihara N, Yamada K, Takikawa O, Kawaguchi R, Isonishi S, Tanaka T, Urashima M. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase serves as a marker of poor prognosis in gene expression profiles of serous ovarian cancer cells. Clinical cancer research. 2005;11:6030–6039. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki Y, Suda T, Furuhashi K, Suzuki M, Fujie M, Hahimoto D, Nakamura Y, Inui N, Nakamura H, Chida K. Increased serum kynurenine/tryptophan ratio correlates with disease progression in lung cancer. Lung cancer. 2010;67:361–365. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takao M, Okamoto A, Nikaido T, Urashima M, Takakura S, Saito M, Saito M, Okamoto S, Takikawa O, Sasaki H, Yasuda M, Ochiai K, Tanaka T. Increased synthesis of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase protein is positively associated with impaired survival in patients with serous-type, but not with other types of, ovarian cancer. Oncology reports. 2007;17:1333–1339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Folgiero V, Goffredo BM, Filippini P, Masetti R, Bonanno G, Caruso R, Bertaina V, Mastronuzzi A, Gaspari S, Zecca M, Torelli GF, Testi AM, Pession A, Locatelli F, Rutella S. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) activity in leukemia blasts correlates with poor outcome in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Oncotarget. 2014;5:2052–2064. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muller AJ, DuHadaway JB, Donover PS, Sutanto-Ward E, Prendergast GC. Inhibition of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, an immunoregulatory target of the cancer suppression gene Bin1, potentiates cancer chemotherapy. Nature medicine. 2005;11:312–319. doi: 10.1038/nm1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Belladonna ML, Grohmann U, Guidetti P, Volpi C, Bianchi R, Fioretti MC, Schwarcz R, Fallarino F, Puccetti P. Kynurenine pathway enzymes in dendritic cells initiate tolerogenesis in the absence of functional IDO. Journal of immunology. 2006;177:130–137. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee GK, Park HJ, Macleod M, Chandler P, Munn DH, Mellor AL. Tryptophan deprivation sensitizes activated T cells to apoptosis prior to cell division. Immunology. 2002;107:452–460. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01526.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munn DH, Shafizadeh E, Attwood JT, Bondarev I, Pashine A, Mellor AL. Inhibition of T cell proliferation by macrophage tryptophan catabolism. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1999;189:1363–1372. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Curti A, Pandolfi S, Valzasina B, Aluigi M, Isidori A, Ferri E, Salvestrini V, Bonanno G, Rutella S, Durelli I, Horenstein AL, Fiore F, Massaia M, Colombo MP, Baccarani M, Lemoli RM. Modulation of tryptophan catabolism by human leukemic cells results in the conversion of CD25− into CD25+ T regulatory cells. Blood. 2007;109:2871–2877. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-036863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakamura T, Shima T, Saeki A, Hidaka T, Nakashima A, Takikawa O, Saito S. Expression of indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase and the recruitment of Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells in the development and progression of uterine cervical cancer. Cancer science. 2007;98:874–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00470.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salaroglio IC, Campia I, Kopecka J, Gazzano E, Orecchia S, Ghigo D, Riganti C. Zoledronic acid overcomes chemoresistance and immunosuppression of malignant mesothelioma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:1128–1142. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fehervari Z, Sakaguchi S. CD4+ Tregs and immune control. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2004;114:1209–1217. doi: 10.1172/JCI23395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Field EH, Matesic D, Rigby S, Fehr T, Rouse T, Gao Q. CD4+CD25+ regulatory cells in acquired MHC tolerance. Immunological reviews. 2001;182:99–112. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1820108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Friberg M, Jennings R, Alsarraj M, Dessureault S, Cantor A, Extermann M, Mellor AL, Munn DH, Antonia SJ. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase contributes to tumor cell evasion of T cell-mediated rejection. International journal of cancer. 2002;101:151–155. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ozaki Y, Edelstein MP, Duch DS. Induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase: a mechanism of the antitumor activity of interferon gamma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85:1242–1246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshida R, Park SW, Yasui H, Takikawa O. Tryptophan degradation in transplanted tumor cells undergoing rejection. Journal of immunology. 1988;141:2819–2823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu WG, Yamamoto N, Takenaka H, Mu J, Tai XG, Zou JP, Ogawa M, Tsutsui T, Wijesuriya R, Yoshida R, Herrmann S, Fujiwara H, Hamaoka T. Molecular mechanisms underlying IFN-gamma-mediated tumor growth inhibition induced during tumor immunotherapy with rIL-12. International immunology. 1996;8:855–865. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.6.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ishio T, Goto S, Tahara K, Tone S, Kawano K, Kitano S. Immunoactivative role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2004;19:319–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2003.03259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Riesenberg R, Weiler C, Spring O, Eder M, Buchner A, Popp T, Castro M, Kammerer R, Takikawa O, Hatz RA, Stief CG, Hofstetter A, Zimmermann W. Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in tumor endothelial cells correlates with long-term survival of patients with renal cell carcinoma. Clinical cancer research. 2007;13:6993–7002. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Opitz CA, Litzenburger UM, Sahm F, Ott M, Tritschler I, Trump S, Schumacher T, Jestaedt L, Schrenk D, Weller M, Jugold M, Guillemin GJ, Miller CL, Lutz C, Radlwimmer B, Lehmann I, et al. An endogenous tumour-promoting ligand of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature. 2011;478:197–203. doi: 10.1038/nature10491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mezrich JD, Fechner JH, Zhang X, Johnson BP, Burlingham WJ, Bradfield CA. An interaction between kynurenine and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor can generate regulatory T cells. Journal of immunology. 2010;185:3190–3198. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martin-Orozco N, Muranski P, Chung Y, Yang XO, Yamazaki T, Lu S, Hwu P, Restifo NP, Overwijk WW, Dong C. T helper 17 cells promote cytotoxic T cell activation in tumor immunity. Immunity. 2009;31:787–798. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Litzenburger UM, Opitz CA, Sahm F, Rauschenbach KJ, Trump S, Winter M, Ott M, Ochs K, Lutz C, Liu XD, Anastasov N, Lehmann I, Hofer T, von Deimling A, Wick W, Platten M. Constitutive IDO expression in human cancer is sustained by an autocrine signaling loop involving IL-6, STAT3 and the AHR. Oncotarget. 2014;5:1038–1051. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sekkai D, Guittet O, Lemaire G, Tenu JP, Lepoivre M. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase expression and activity in macrophages by 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid, a tryptophan metabolite. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 1997;340:117–123. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.9913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hayashi T, Mo JH, Gong X, Rossetto C, Jang A, Beck L, Elliott GI, Kufareva I, Abagyan R, Broide DH, Lee J, Raz E. 3-Hydroxyanthranilic acid inhibits PDK1 activation and suppresses experimental asthma by inducing T cell apoptosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:18619–18624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709261104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fallarino F, Grohmann U, You S, McGrath BC, Cavener DR, Vacca C, Orabona C, Bianchi R, Belladonna ML, Volpi C, Santamaria P, Fioretti MC, Puccetti P. The combined effects of tryptophan starvation and tryptophan catabolites down-regulate T cell receptor zeta-chain and induce a regulatory phenotype in naive T cells. Journal of immunology. 2006;176:6752–6761. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fallarino F, Grohmann U, Vacca C, Bianchi R, Orabona C, Spreca A, Fioretti MC, Puccetti P. T cell apoptosis by tryptophan catabolism. Cell death and differentiation. 2002;9:1069–1077. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weber WP, Feder-Mengus C, Chiarugi A, Rosenthal R, Reschner A, Schumacher R, Zajac P, Misteli H, Frey DM, Oertli D, Heberer M, Spagnoli GC. Differential effects of the tryptophan metabolite 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid on the proliferation of human CD8+ T cells induced by TCR triggering or homeostatic cytokines. European journal of immunology. 2006;36:296–304. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Favre D, Mold J, Hunt PW, Kanwar B, Loke P, Seu L, Barbour JD, Lowe MM, Jayawardene A, Aweeka F, Huang Y, Douek DC, Brenchley JM, Martin JN, Hecht FM, Deeks SG, et al. Tryptophan catabolism by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 alters the balance of TH17 to regulatory T cells in HIV disease. Science translational medicine. 2010;2:32ra36. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zaher SS, Germain C, Fu H, Larkin DF, George AJ. 3-hydroxykynurenine suppresses CD4+ T-cell proliferation, induces T-regulatory-cell development, and prolongs corneal allograft survival. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2011;52:2640–2648. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Richardson DR, Kalinowski DS, Lau S, Jansson PJ, Lovejoy DB. Cancer cell iron metabolism and the development of potent iron chelators as anti-tumour agents. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2009;1790:702–717. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Testa U, Louache F, Titeux M, Thomopoulos P, Rochant H. The iron-chelating agent picolinic acid enhances transferrin receptors expression in human erythroleukaemic cell lines. British journal of haematology. 1985;60:491–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1985.tb07446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fernandez PJ, Johnson GS. Selective toxicity induced by picolinic acid in simian virus 40-transformed cells in tissue culture. Cancer research. 1977;37:4276–4279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guillemin GJ, Cullen K, Lim C, Smythe GA, Garner B, Kapoor V, Takikawa O, Brew BJ. Characterization of the kynurenine pathway in human neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:12884–12892. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4101-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leuthauser SW, Oberley LW, Oberley TD. Antitumor activity of picolinic acid in CBA/J mice. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1982;68:123–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ogata S, Takeuchi M, Fujita H, Shibata K, Okumura K, Taguchi H. Apoptosis induced by niacin-related compounds in K562 cells but not in normal human lymphocytes. Bioscience, biotechnology, and biochemistry. 2000;64:1142–1146. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bosco MC, Rapisarda A, Reffo G, Massazza S, Pastorino S, Varesio L. Macrophage activating properties of the tryptophan catabolite picolinic acid. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2003;527:55–65. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0135-0_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Melillo G, Cox GW, Radzioch D, Varesio L. Picolinic acid, a catabolite of L-tryptophan, is a costimulus for the induction of reactive nitrogen intermediate production in murine macrophages. Journal of immunology. 1993;150:4031–4040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Varesio L, Clayton M, Blasi E, Ruffman R, Radzioch D. Picolinic acid, a catabolite of tryptophan, as the second signal in the activation of IFN-gamma-primed macrophages. Journal of immunology. 1990;145:4265–4271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ruffmann R, Schlick R, Chirigos MA, Budzynsky W, Varesio L. Antiproliferative activity of picolinic acid due to macrophage activation. Drugs under experimental and clinical research. 1987;13:607–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ruffmann R, Welker RD, Saito T, Chirigos MA, Varesio L. In vivo activation of macrophages but not natural killer cells by picolinic acid (PLA) Journal of immunopharmacology. 1984;6:291–304. doi: 10.3109/08923978409028605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bosco MC, Rapisarda A, Massazza S, Melillo G, Young H, Varesio L. The tryptophan catabolite picolinic acid selectively induces the chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha and -1 beta in macrophages. Journal of immunology. 2000;164:3283–3291. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Guillemin GJ, Brew BJ. Implications of the kynurenine pathway and quinolinic acid in Alzheimer's disease. Redox report. 2002;7:199–206. doi: 10.1179/135100002125000550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Adams S, Braidy N, Bess A, Brew BJ, Grant RS, Teo C, Guillemin GJ. The kynurenine pathway in brain tumor pathogenesis. Cancer research. 2012;72:5649–5657. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Prendergast GC. Immune escape as a fundamental trait of cancer: focus on IDO. Oncogene. 2008 doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Prendergast GC. Cancer: Why tumours eat tryptophan. Nature. 2011;478:192–194. doi: 10.1038/478192a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Serio CD, Cozzi A, Angeli I, Doria L, Micucci I, Pellerito S, Mirone P, Masotti G, Moroni F, Tarantini F. Kynurenic Acid Inhibits the Release of the Neurotrophic Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF)-1 and Enhances Proliferation of Glia Cells, in vitro. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2005:25981–993. doi: 10.1007/s10571-005-8469-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Thaker AI, Rao MS, Bishnupuri KS, Kerr TA, Foster L, Marinshaw JM, Newberry RD, Stenson WF, Ciorba MA. IDO1 metabolites activate beta-catenin signaling to promote cancer cell proliferation and colon tumorigenesis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:416–425. e411–414. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bresjanac M, Antauer G. Reactive Astrocytes of the Quinolinic Acid-Lesioned Rat Striatum Express GFRalpha1 as Well as GDNF in Vivo. Exp Neurol. 2000;164:53–59. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hansford LM, Marshall GM. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) family ligands reduce the sensitivity of neuroblastoma cells to pharmacologically induced cell death, growth arrest and differentiation. Neurosci Lett. 2005;389:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sahm F, Oezen I, Opitz CA, Radlwimmer B, von Deimling A, Ahrendt T, Adams S, Bode HB, Guillemin GJ, Wick W, Platten M. The endogenous tryptophan metabolite and NAD+ precursor quinolinic acid confers resistance of gliomas to oxidative stress. Cancer research. 2013;73:3225–3234. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Belenky P, Bogan KL, Brenner C. NAD+ metabolism in health and disease. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2007;32:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kim MY, Zhang T, Kraus WL. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by PARP-1: ‘PAR-laying’ NAD+ into a nuclear signal. Genes & development. 2005;19:1951–1967. doi: 10.1101/gad.1331805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Walczak K, Zurawska M, Kis J, Starownik R, Zgrajka W, Bar K, Turski WA, Rzeski W. Kynurenic acid in human renal cell carcinoma: its antiproliferative and antimigrative action on Caki-2 cells. Amino acids. 2012;43:1663–1670. doi: 10.1007/s00726-012-1247-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chan-Hui PY, Weaver R. Human mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase mediates the stress-induced activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades. The Biochemical journal. 1998;336:599–609. doi: 10.1042/bj3360599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dhillon AS, Hagan S, Rath O, Kolch W. MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3279–3290. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wagner EF, Nebreda AR. Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nature reviews Cancer. 2009;9:537–549. doi: 10.1038/nrc2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Walczak K, Turski WA, Rzeski W. Kynurenic acid enhances expression of p21 Waf1/Cip1 in colon cancer HT-29 cells. Pharmacological reports : PR. 2012;64:745–750. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(12)70870-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Visconti R, Grieco D. New insights on oxidative stress in cancer. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2009;12:240–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ayala A, Munoz MF, Arguelles S. Lipid peroxidation: production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;2014:360438. doi: 10.1155/2014/360438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Goldstein LE, Leopold MC, Huang X, Atwood CS, Saunders AJ, Hartshorn M, Lim JT, Faget KY, Muffat JA, Scarpa RC, Chylack LT, Jr, Bowden EF, Tanzi RE, Bush AI. 3-Hydroxykynurenine and 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid generate hydrogen peroxide and promote alpha-crystallin cross-linking by metal ion reduction. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7266–7275. doi: 10.1021/bi992997s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hiraku Y, Inoue S, Oikawa S, Yamamoto K, Tada S, Nishino K, Kawanishi S. Metal-mediated oxidative damage to cellular and isolated DNA by certain tryptophan metabolites. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:349–356. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.2.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Smith AJ, Smith RA, Stone TW. 5-Hydroxyanthranilic acid, a tryptophan metabolite, generates oxidative stress and neuronal death via p38 activation in cultured cerebellar granule neurones. Neurotoxicity research. 2009;15:303–310. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hiramatsu R, Hara T, Akimoto H, Takikawa O, Kawabe T, Isobe K, Nagase F. Cinnabarinic acid generated from 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid strongly induces apoptosis in thymocytes through the generation of reactive oxygen species and the induction of caspase. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103:42–53. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Morita T, Saito K, Takemura M, Maekawa N, Fujigaki S, Fujii H, Wada H, Takeuchi S, Noma A, Seishima M. 3-Hydroxyanthranilic acid, an L-tryptophan metabolite, induces apoptosis in monocyte-derived cells stimulated by interferon-gamma. Ann Clin Biochem. 2001;38:242–251. doi: 10.1258/0004563011900461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Backhaus C, Rahman H, Scheffler S, Laatsch H, Hardeland R. NO scavenging by 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid and 3-hydroxykynurenine: N-nitrosation leads via oxadiazoles to o-quinone diazides. Nitric Oxide. 2008;19:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Christen S, Peterhans E, Stocker R. Antioxidant activities of some tryptophan metabolites: possible implication for inflammatory diseases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87:2506–2510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Giles GI, Collins CA, Stone TW, Jacob C. Electrochemical and in vitro evaluation of the redox-properties of kynurenine species. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003:300719–724. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02917-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Latini A, Rodriguez M, Borba Rosa R, Scussiato K, Leipnitz G, Reis de Assis D, da Costa Ferreira G, Funchal C, Jacques-Silva MC, Buzin L, Giugliani R, Cassina A, Radi R, Wajner M. 3-Hydroxyglutaric acid moderately impairs energy metabolism in brain of young rats. Neuroscience. 2005;135:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Leipnitz G, Schumacher C, Dalcin KB, Scussiato K, Solano A, Funchal C, Dutra-Filho CS, Wyse AT, Wannmacher CM, Latini A, Wajner M. In vitro evidence for an antioxidant role of 3-hydroxykynurenine and 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid in the brain. Neurochem Int. 2007;50:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Platenik J, Stopka P, Vejrazka M, Stipek S. Quinolinic acid-iron(ii) complexes: slow autoxidation, but enhanced hydroxyl radical production in the Fenton reaction. Free Radic Res. 2001;34:445–459. doi: 10.1080/10715760100300391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kubicova L, Hadacek F, Chobot V. Quinolinic acid: neurotoxin or oxidative stress modulator? Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:21328–21338. doi: 10.3390/ijms141121328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rose DP. The influence of sex, age and breast cancer on tryptophan metabolism. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 1967;18:221–225. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(67)90161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sakurai K, Amano S, Enomoto K, Kashio M, Saito Y, Sakamoto A, Matsuo S, Suzuki M, Kitajima A, Hirano T, Negishi N. [Study of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in patients with breast cancer] Gan to kagaku ryoho Cancer & chemotherapy. 2005;32:1546–1549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rose DP, Randall ZC. Tryptophan metabolism in early and advanced breast cancer and carcinoma of the cervix. Clinica chimica acta. 1972;40:276–280. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(72)90284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yu J, Sun J, Wang SE, Li H, Cao S, Cong Y, Liu J, Ren X. Upregulated expression of indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase in primary breast cancer correlates with increase of infiltrated regulatory T cells in situ and lymph node metastasis. Clinical & developmental immunology. 2011;2011:469135. doi: 10.1155/2011/469135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yu J, Du W, Yan F, Wang Y, Li H, Cao S, Yu W, Shen C, Liu J, Ren X. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells suppress antitumor immune responses through IDO expression and correlate with lymph node metastasis in patients with breast cancer. Journal of immunology. 2013;190:3783–3797. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mansfield AS, Heikkila PS, Vaara AT, von Smitten KA, Vakkila JM, Leidenius MH. Simultaneous Foxp3 and IDO expression is associated with sentinel lymph node metastases in breast cancer. BMC cancer. 2009;9:231. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rose DP, Randall ZC. Reassessment of tryptophan metabolism in breast cancer five years after an initial study. Clinica chimica acta. 1973;45:33–36. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(73)90141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lyon DE, Walter JM, Starkweather AR, Schubert CM, McCain NL. Tryptophan degradation in women with breast cancer: a pilot study. BMC research notes. 2011;4:156. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Jacquemier J, Bertucci F, Finetti P, Esterni B, Charafe-Jauffret E, Thibult ML, Houvenaeghel G, Van den Eynde B, Birnbaum D, Olive D, Xerri L. High expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in the tumour is associated with medullary features and favourable outcome in basal-like breast carcinoma. International journal of cancer. 2012;130:96–104. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, Antipin Y, Reva B, Goldberg AP, Sander C, Schultz N. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer discovery. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, Cerami E, Sander C, Schultz N. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Science signaling. 2013;6:pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Mosca E, Alfieri R, Merelli I, Viti F, Calabria A, Milanesi L. A multilevel data integration resource for breast cancer study. BMC systems biology. 2010;4:76. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Chen DT, Nasir A, Culhane A, Venkataramu C, Fulp W, Rubio R, Wang T, Agrawal D, McCarthy SM, Gruidl M, Bloom G, Anderson T, White J, Quackenbush J, Yeatman T. Proliferative genes dominate malignancy-risk gene signature in histologically-normal breast tissue. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2010;119:335–346. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0344-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Cheng AS, Culhane AC, Chan MW, Venkataramu CR, Ehrich M, Nasir A, Rodriguez BA, Liu J, Yan PS, Quackenbush J, Nephew KP, Yeatman TJ, Huang TH. Epithelial progeny of estrogen-exposed breast progenitor cells display a cancer-like methylome. Cancer research. 2008;68:1786–1796. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Karnoub AE, Dash AB, Vo AP, Sullivan A, Brooks MW, Bell GW, Richardson AL, Polyak K, Tubo R, Weinberg RA. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449:557–563. doi: 10.1038/nature06188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lee S, Stewart S, Nagtegaal I, Luo J, Wu Y, Colditz G, Medina D, Allred DC. Differentially expressed genes regulating the progression of ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive breast cancer. Cancer research. 2012;72:4574–4586. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]