Abstract

Background

Homogeneous ventilation is important for prevention of ventilator-induced lung injury. Electrical impedance tomography (EIT) has been used to identify optimal PEEP by detection of homogenous ventilation in non-dependent and dependent lung regions. We aimed to compare the ability of volumetric capnography and EIT in detecting homogenous ventilation between these lung regions.

Methods

Fifteen mechanically-ventilated patients after cardiac surgery were studied. Ventilator settings were adjusted to volume-controlled mode with a fixed tidal volume (Vt) of 6–8 ml kg−1 predicted body weight. Different PEEP levels were applied (14 to 0 cm H2O, in steps of 2 cm H2O) and blood gases, Vcap and EIT were measured.

Results

Tidal impedance variation of the non-dependent region was highest at 6 cm H2O PEEP, and decreased significantly at 14 cm H2O PEEP indicating decrease in the fraction of Vt in this region. At 12 cm H2O PEEP, homogenous ventilation was seen between both lung regions. Bohr and Enghoff dead space calculations decreased from a PEEP of 10 cm H2O. Alveolar dead space divided by alveolar Vt decreased at PEEP levels ≤6 cm H2O. The normalized slope of phase III significantly changed at PEEP levels ≤4 cm H2O. Airway dead space was higher at higher PEEP levels and decreased at the lower PEEP levels.

Conclusions

In postoperative cardiac patients, calculated dead space agreed well with EIT to detect the optimal PEEP for an equal distribution of inspired volume, amongst non-dependent and dependent lung regions. Airway dead space reduces at decreasing PEEP levels.

Keywords: capnography, mechanical ventilation, peep, ventilator induced lung injury

Editor's key points.

This pilot study compared volumetric capnography and electrical impedance tomography (EIT) in detecting distribution of ventilation after cardiac surgery.

EIT values approximated to calculated dead space and detected optimal PEEP to equalize gas distribution in dependent and non-dependent lung regions.

At 12 cm H20 PEEP, ventilation was distributed homogeneously between dependent and non-dependent regions.

However, excessive PEEP applied to healthy lungs caused airway distension rather than improving alveolar ventilation.

Ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) is a well-recognized complication of mechanical ventilation, which occurs in both patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)1 and healthy lungs.2,3 The deleterious effects of mechanical ventilation are caused by large amounts of stress and strain acting on lung tissue, as a result of inhomogeneous ventilation of the lungs.4–6 Although, protective lung strategies using low tidal volumes have been strongly recommended to prevent the development of VILI, the amount of PEEP that should be applied is still under debate.7,8 The positive effect of PEEP depends on the recruitability of lung tissue, which varies between patients,9,10 but also from day to day. Therefore, setting the PEEP level without a reliable tool to estimate the distribution of inspiratory tidal volume (Vt) at the bedside is a challenging activity.

Volumetric capnography (Vcap) is a non-invasive technique that describes the CO2 exhalation during one breath, and can be used to calculate alveolar and airway dead space.11 Because elimination of CO2 depends on alveolar ventilation and pulmonary perfusion, V/Q mismatches in either hyperinflated or collapsed lung areas will affect the amount of exhaled CO2 and thereby Vcap. Recently, a multi-centre observational study showed that an increased dead space fraction in patients with ARDS was associated with an increased mortality.12 Several studies showed the capability of Vcap in detecting optimal PEEP level during mechanical ventilation in various lung pathological conditions.13–15 Böhm and colleagues14 showed in 11 morbidly obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery, Slope III (SIII) has a high sensitivity and specificity to detect lung recruitment. They concluded that SIII was useful for identifying appropriate levels of PEEP in those patients. In 20 obese patients undergoing laparoscopic bariatric surgery Tusman and colleagues13 found that both Vcap and pulse-oximetry, as compared with respiratory compliance, are accurate parameters for the detection of alveolar collapse. Fengmei and colleagues15 found that best PEEP based on dead space fraction corresponded well with best PEEP according to highest respiratory compliance, in 23 ARDS patients. Therefore, Vcap is a promising technique to detect alveolar collapse and recruitment at the bedside.

Electrical Impedance Tomography (EIT) is a non-invasive, radiation-free, real time imaging modality, which has proved to correlate well with Computed Tomography (CT), according to assessment of changes in gas volume and tidal volume.16–18 Recently, we showed that the intratidal gas distribution calculated from EIT measurements, is able to define a patient specific PEEP level, at which the lungs are homogeneously ventilated among dependent and non-dependent lung regions. This parameter was evaluated in both experimental studies and in patients,19–21 but also during pressure support ventilation (PSV), Neurally Assisted Ventilatory Assist (NAVA) and pressure control ventilation (PCV).22,23 In addition, EIT has been used to visualize hyperinflation in the non-dependent region at a certain PEEP level when pixel-compliance is decreased.24,25

Suter and colleagues26 defined optimal PEEP as the balance of adequate levels, good compliance and elimination of CO2. However, we believe that stress and strain are important contributors to lung injury, as both factors increase with inhomogeneous ventilation.5,6 Therefore, the main goal of this study was to compare the results of Vcap measurements with that of EIT in finding the optimal PEEP, with an equal distribution of the inspiratory volume among the dependent and the non-dependent regions.

Methods

Study population

In this pilot-study, 15 mechanically ventilated patients, who had undergone coronary-artery bypass grafting and/or cardiac-valve surgery, admitted to the cardiothoracic intensive care unit (ICU) were included. The local medical ethical committee approved the study protocol and written informed consent was obtained from each patient or their relatives. Data were collected between January and July 2014.

The inclusion criteria were age >18 yrs, written informed consent, haemodynamically stable. Exclusion criteria were: presence of a cardiac pacemaker, pneumothorax, thoracic deformations and severe airflow limitation (defined as forced expiratory volume in 1 s below 70% of forced vital capacity).

Study protocol

For Vcap measurements a mainstream CO2 sensor was placed between the tracheal tube and ventilator tubing's, and was connected to a NICO-capnograph (Novametrix, Wallinford, Connecticut, USA). Specific software (Analysis plus, Novametrix, Wallinford, Connecticut, USA) was used to record all Vcap data. In order to perform electrical impedance tomography (EIT) measurements, a silicon belt with 16 electrodes was placed around the thoracic cage between the 5th and 6th intercostal space (Pulmovista 500, Dräger, Lübeck, Germany). Ventilator settings were set to volume-controlled mode (Evita-infinity, Dräger, Lübeck, Germany), with a fixed tidal volume of 6–8 ml kg−1 predicted body weight and inspiration/expiration (I/E) ratio of 1:2. We deliberately choose volume control in order to avoid a change in the min volume because of differences in lung compliance at different levels of PEEP. The initial setting of the respiratory rate and fraction of inspired oxygen was adjusted to maintain an end-tidal carbon dioxide tension and oxygen saturation within a range of 35–45 mm Hg and 97–100%, respectively. PEEP was set according to the attending physician. Vt, respiratory rate (RR), I/E ratio remained unchanged throughout the entire study period.

We are reluctant to apply high levels of PEEP (>15 cm H2O) in postoperative patients after cardiac surgery who obviously have no ALI or ARDS, as these patients are generally prone to haemodynamic instability. Therefore, the patients were not subjected to recruitment manoeuvers. After baseline measurements of Vcap and EIT, the PEEP level was increased to 14 cm H2O. This PEEP level was maintained for 15–20 min in order to reach a steady state situation, as assessed by a stable signal of the volume of exhaled carbon dioxide (VCO2). Thereafter, the PEEP was decreased from 14 to 0 cm H2O PEEP in steps of 2 cm H2O. Each PEEP level was applied for five to 10 min depending on haemodynamically stability. Blood gas analysis, Vcap and EIT were measured during each PEEP step.

Data analysis

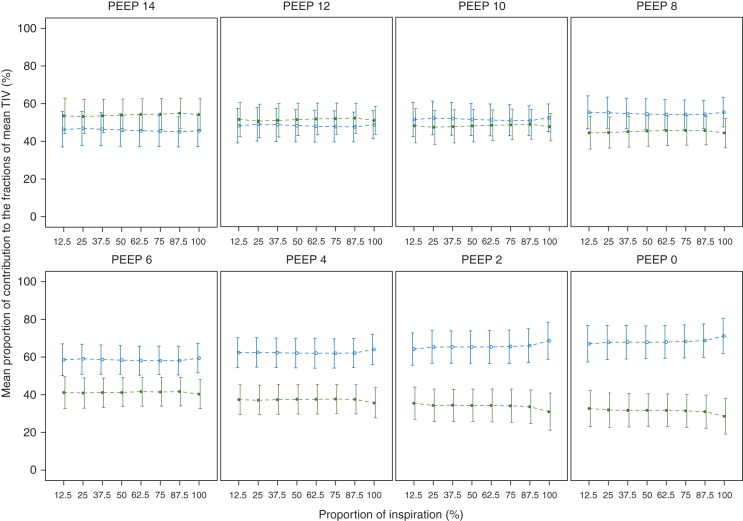

Volumetric capnography; model fitting and parameters

Vcap, which is constructed from expired CO2 concentration and expired volume, can be represented by a mathematical function, which is previously introduced by Tusman and colleagues.27,28 This makes the analysis of the Vcap data less susceptible to noise. To obtain this mathematical function from Vcap data, a non-linear least square curve fitting algorithm according to Tusman and colleagues was used in a custom-made Matlab® (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) program. From this model, parameters were derived for further analysis. First, the Vcap curve was divided into three phases (Phase I, II and III) (Fig. 1). Phase I indicates the CO2 volume originated from the airways, whereas phase III is the CO2 from the alveoli. Phase II therefore is the phase with CO2 from both the airways and alveoli. The inflection point of Phase II (Point A), which is determined by the maximum of the first derivative of the fitted model, was defined as the mean airway-alveolar interface that separates the airway from the alveolar compartment. Airway dead space (VDaw) is the volume from the beginning of the expiration until point A. Slope II (SII) is the slope of the inflection point of Phase II. Slope III (SIII) is the slope of phase III, which is calculated according to Tusman and colleagues.27,28 Therefore, phaseIII was divided into three even sized segments. A line was fitted through the second segment of phaseIII by the least-square method. The slope of this fitted line was determined as SIII. Thereafter slope III was divided by the fraction of end tidal CO2 (FECO2) in order to normalize the value and make it comparable between patients.28,29 Normalized Slope III (SnIII) represents the homogeneity of ventilation and pulmonary perfusion, which is considered as a good indicator of the global V/Q matching. SnIII increases in lung conditions associated with a mismatch of ventilation and perfusion such as atelectasis or pulmonary artery embolism, whereas low values indicate homogeneous V/Q matching.

Fig 1.

Schematic model of three phases of the expiration. The Vcap curve is divided in three phases. Phase I represents exhaled CO2 from the airways, whereas phase III represents exhaled CO2 from the alveoli. Phase II is a mixed phase with CO2 from both the airways and alveoli. Point A is the inflection point of phase II, which is the theoretical point where the airway compartment is separated from the alveolar compartment. VDaw, airway dead space, Vtalv, alveolar tidal volume, Vt, tidal volume.

Physiological dead space was calculated according to the formula developed by Bohr, and the Enghoff modification of Bohr's formula30 (formula 1+formula 2):

(Mean alveolar partial pressure of CO2 ; mixed expired partial pressure of CO2 )

| (1) |

| (2) |

Alveolar dead space (VDalv) was computed by subtracting VDaw from VDEnghoff. We chose to subtract VDaw from VDEnghoff as the VDEnghoff contains all causes of V/Q inhomogeneity, whereas the Bohr formula is not supposed to contain shunts and low V/Q regions. The ratio of VDalv to alveolar tidal volume (VTalv) was obtained by dividing VDalv by VTalv (VTalv=VT−VDaw), in which VTalv represents alveolar tidal volume.

EIT parameters

EIT data were recorded with a sample frequency of 20 Hz. Data was reconstructed and analysed using special software (EITdiag, Dräger, Lübeck, Germany). For each PEEP level, 10 to 20 consecutive breaths at the end of each PEEP step were selected for analysis, with the assumption that the lungs were best adapted to the ventilator settings at that time. EIT data contains signals induced by the respiratory system and the circulatory system. Therefore, to filter out signals related to the circulatory system, EIT data was filtered using a low pass-filter set to 40 beats min-1. The reconstructed image was represented as a ventilation distribution map, which was generated by tidal impedance changes caused, by inspiration and expiration. These impedance changes are presented as tidal impedance variation (TIV) and have been shown to correlate well with gas volume changes, as measured by CT-scans.16–18 The surface area of the distribution map was divided into two equal regions of interest (ROIs), to know the non-dependent and dependent lung regions (Supplementary data, Fig. S1). The surface area of the EIT map was kept equal for all PEEP steps.

The intratidal gas distribution (ITV) was developed by Löwhagen, and colleagues21 (formula 3). The ITV describes the amount of the impedance distributed to each region of interest within one inspiration. For this calculation Löwhagen and colleagues21 divided the inspiratory part of the global impedance curve into eight equal volume sections. In other words each part of the inspiration is 12.5% of the entire inspiration. Thereafter, they transposed the time needed for each section of the inspiration to the regional curves. In this way they were able to calculate the contribution of four different regions of interest to the inspiration, during a single breath. According to our previous publications19,20,22,31 we calculated the ITV for two instead of four regions of interest. Using the ITV calculation one is able to analyse the ventilation homogeneity during the inspiration. In order to reliably calculate the ITV, the filtered EIT signals were re-sampled with a frame rate of 40 Hz. This step is important in order to divide the inspiratory part of the global TIV curve reliably into eight iso-volume sections (ITV, Intratidal Gas Distribution; TIV, Tidal Impedance Variation; ROI, Region of Interest; t, iso-volume part).21

| (3) |

In addition to the capnography and EIT parameters we also calculated the dynamic compliance. Dynamic compliance was calculated by dividing the expiratory tidal volume by Peak Inspiratory Pressure (PIP) minus PEEP.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 21 (Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented as mean (sd) unless otherwise specified. Normal distribution of the data was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, whereas homoscedasticity was tested using the Brown-Forsythe test. Changes in Vcap and EIT parameters during the entire protocol were tested using mixed linear models. Differences between two sequential PEEP steps were tested using the paired Student's t-test for normal distributed data, and using the Wilcoxon rank sum test for not normal distributed data. For all statistical test P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The initial physiological data, measured shortly before 14 cm H2O was applied, is summarized in Table 1. During the different PEEP levels, blood gases and dynamic compliance remained stable, down to a PEEP level of 2 cm H2O and decreased significantly at 0 PEEP (ZEEP) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Data are presented as mean (sd) unless otherwise specified. Predicted body weight (PBW), Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), Coronary artery by-pass graft (CABG), Arterial partial pressure of O2 , Fraction of inspired oxygen , Arterial partial pressure of CO2

| Patient characteristics | |||

| No. of patients | 15 | ||

| Age (yr) | 70 (8) | ||

| Male/Female | 13/2 | ||

| Height (cm) | 176 (13) | ||

| Weight (kg) | 86 (18) | ||

| Predicted body weight (kg) | 70 (13) | ||

| BMI | 28 (4) | ||

| CPB time (min) | 112 (35) | ||

| Type of surgery | CABG | Valve replacement | CABG+Valve replacement |

| 10 | 3 | 2 | |

| Haemodynamic data at ICU admission | |||

| Mean arterial pressure (mm Hg) | 70 (9) | ||

| Heart rate (BPM) | 77 (15) | ||

| Ventilator settings and respiratory measurements at ICU admission | |||

| Positive end-expiratory pressure (cm H2O) | 8 (1) | ||

| Peak inspiratory pressure (cm H2O) | 22 (2) | ||

| Expiratory tidal volume (ml) | 494 (74) | ||

| Expiratory tidal volume/Predicted body weight (ml kg PBW−1) | 7.1 (0.6) | ||

| Respiratory rate(Bpm) | 17 (2) | ||

| (mm Hg) | 350 (101) | ||

| (mm Hg) | 42.2 (4.5) | ||

Table 2.

Data are presented as mean (sd). The first statistical change compared with 14 cm H2O PEEP is indicated by *P<0.05 was considered significant. Tidal volume (VT), Airway dead space (VDaw), Alveolar dead space (VDalv), Alveolar dead space to alveolar tidal volume ratio (VDalv/VTalv), Normalized slope of phase III (SnIII), Amount of expired CO2 within one breath (VTCO2,br), Volume of phase III to tidal volume ratio (VIII/VT), Arterial minus end-tidal partial pressure of CO2 (Pa-ETCO2), Arterial partial pressure of O2 , Arterial partial pressure of CO2 , Fraction of inspired oxygen

| Dead space variables, blood gas analysis and compliance during the decremental PEEP trial | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEEP (cm H2O) | 14 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| VT (ml) | 472 (80) | 476 (77) | 474 (80) | 473 (77) | 472 (76) | 471 (78) | 474 (81) | 473 (81) |

| VDaw (ml) | 214 (40) | 209 (42) | 204 (39) | 196 (40)* | 188 (39) | 182 (36) | 174 (32) | 167 (26) |

| VDalv (ml) | 52 (37) | 52 (34) | 47 (31) | 45 (33) | 42 (33)* | 35 (32) | 39 (31) | 35 (29) |

| VDBohr/VT | 0.48 (0.06) | 0.47 (0.07) | 0.45 (0.07)* | 0.43 (0.07) | 0.40 (0.07) | 0.38 (0.07) | 0.35 (0.07) | 0.33 (0.07) |

| VDEnghoff/VT | 0.57 (0.07) | 0.55 (0.08) | 0.53 (0.08)* | 0.52 (0.08) | 0.49 (0.08) | 0.47 (0.09) | 0.46 (0.08) | 0.44 (0.08) |

| VDalv/VTalv | 0.19 (0.11) | 0.18 (0.1) | 0.17 (0.09) | 0.15 (0.09) | 0.14 (0.1)* | 0.12 (0.1) | 0.13 (0.09) | 0.11 (0.09) |

| SnIII (mm Hg ml−1) | 0.95 (1.19) | 0.73 (0.64) | 0.62 (0.31) | 0.62 (0.43) | 0.58 (0.33) | 0.48 (0.25)* | 0.47 (0.26) | 0.50 (0.21) |

| VTCO2,br (ml) | 12.5 (3.3) | 13.3 (3.7)* | 13.9 (3.7) | 14.3 (3.6) | 14.7 (3.7) | 15.2 (3.7) | 15.7 (3.8) | 16.0 (3.9) |

| VIII/VT | 0.42 (0.14) | 0.39 (0.13) | 0.41 (0.14) | 0.43 (0.13)* | 0.46 (0.13) | 0.46 (0.13) | 0.48 (0.12) | 0.51 (0.11) |

| Pa-ETCO2 (mm Hg) | 3.6 (2.8) | 3.4 (2.5) | 3.7 (2.6) | 3.2 (2.5) | 2.9 (2.7) | 2.7 (2.4) | 3.1 (2.4) | 2.8 (2.5)* |

| (mm Hg) | 43 (5) | 43 (5) | 44 (5) | 43 (5) | 42 (5) | 42 (5) | 42 (5) | 41 (5)* |

| (mm Hg) | 138 (35) | 140 (32) | 145 (25) | 145 (24) | 145 (23) | 139 (21) | 132 (24) | 127 (23)* |

| (mm Hg) | 346 (87) | 349 (80) | 359 (71) | 371 (71) | 372 (68) | 357 (65) | 338 (72) | 324 (70)* |

| Dynamic compliance (ml cm H2O−1) | 34 (6) | 36 (8) | 35 (6) | 35 (7) | 35 (7) | 34 (7) | 33 (7) | 31 (7)* |

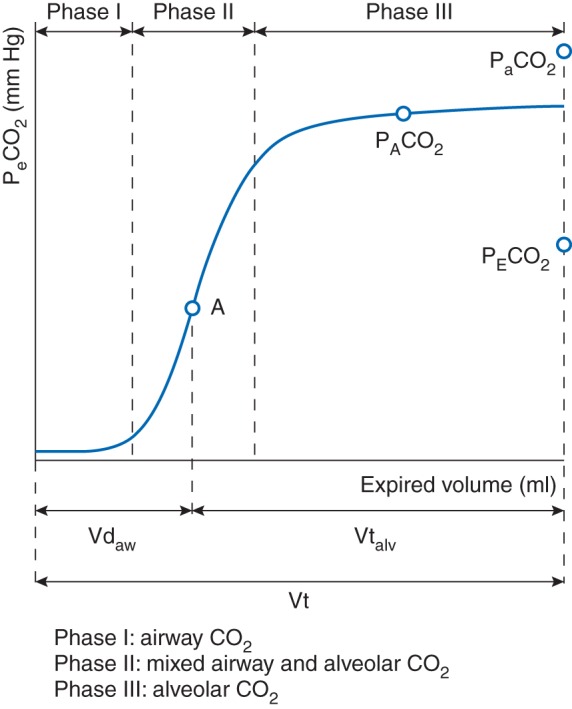

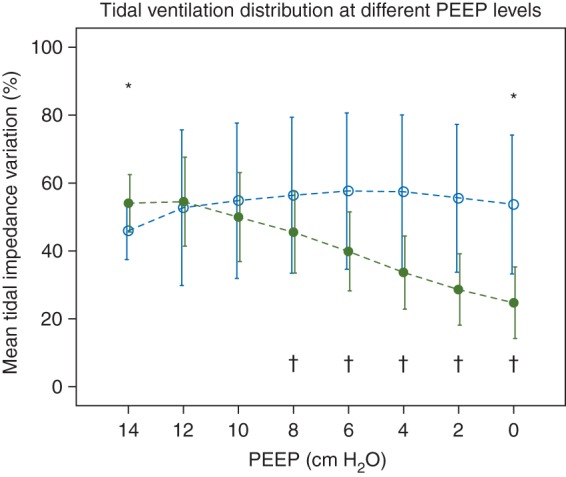

Figure 2 shows the TIV for the dependent and non-dependent lung region. The 14 cm H2O PEEP step was chosen as reference, and the TIV of both lung regions together was set to 100% at 14 cm H2O, Therefore, at lower PEEP levels the sum of TIV of both regions can be more or less than 100%, as compared with PEEP 14 cm H2O. At 14 cm H2O of PEEP, most of the ventilation was distributed to the dependent lung region and from PEEP level of 10 cm H2O and lower, the non-dependent lung region became predominant ventilated (Fig. 2). TIV in the dependent lung region decreased during each PEEP step reduction from a PEEP of 12 cm H2O, indicating less ventilation at lower PEEP levels as a result of collapse (Fig. 2). TIV in the non-dependent region had the highest value at 6 cm H2O of PEEP (Fig. 2). In addition, ventilation was evenly distribution among dependent and non-dependent regions at 12 and 10 cmH2O PEEP (Fig. 3).

Fig 2.

Tidal Impedance Variation at different PEEP levels. Data are shown as mean (sd). In the dependent lung region the ventilation distribution was decreased when PEEP was lowered, whereas the non-dependent region received more ventilation as compared with PEEP 14 cm H2O. * Indicates a significant reduction in TIV of the non-dependent region according to 6 cm H2O. † Indicates a significant reduction in TIV of the dependent region as compared with 12 cm H2O. Dashed lines represents the interpolation lines; open circles=non-dependent region; solid circles=dependent region. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Fig 3.

Mean intratidal gas distribution (ITV) curve of all the patients at each PEEP step. Data are shown as mean (sd). ITV curve represents the mean percentile contribution (%) of ventilation distribution in non-dependent and dependent lung regions during the entire inspiration. At PEEP 12 and 10 cm H2O, intratidal gas distribution curves stayed close to each other, showing equal distribution to both regions. Dashed lines represents the interpolation lines; open circles=non-dependent region; solid circles=dependent region.

Table 2 shows changes in different Vcap parameters. VDBohr/VT and VDEnghoff/VT significantly decreased from a PEEP of 10 cm H2O and less as compared with 14 cm H2O PEEP. The ratio of alveolar dead space to alveolar tidal volume significantly decreased from a PEEP level of 6 cm H2O and less as compared with 14 cm H2O PEEP. The normalized slope of phase III significantly changed at a PEEP levels of 4 cm H2O or less, whereas volume of phase III corrected for tidal volume (VIII/VT) increased significantly, as compared with 14 cm H2O PEEP at ≤8 cm H2O PEEP, indicating more alveolar ventilation at lower PEEP levels. In addition, VDaw decreased significantly from a PEEP level of 8 cm H2O or less. Shunt fraction calculated as the difference between arterial CO2 minus end-tidal CO2 (Pa-ETCO2)32 only significantly differed at ZEEP.

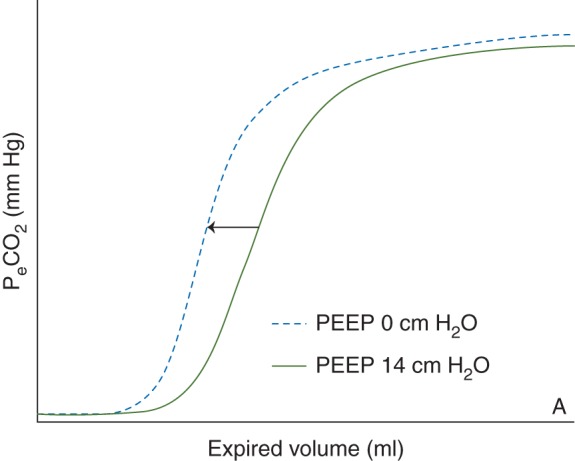

Figure 4a shows the effect of PEEP on the Vcap curve. When lower PEEP levels are applied the Vcap curve is shifted to the left, as a consequence of decreased VDaw. VDaw/VT significantly decreased at 10 cm H2O and lower as compared with 14 cm H2O PEEP (Table 2).

Fig 4.

Effect of increased PEEP on the Vcap curve. Figure 4 demonstrates the effect of two PEEP levels on the Vcap curve. As a result of the PEEP application the Vcap curve shifts to the right, indicating an increase in airway dead space. PeCO2 = Expiratory carbondioxide pressure; Vcap = volumetric capnography.

Discussion

In this study we found that dead space calculations according to Bohr and Enghoff agreed well with the PEEP level, resulting in homogeneous ventilation as measured by EIT. In contrast, VDalv/VTalv and SnIII were insensitive to detect lung inhomogeneity. In addition, we found that in relatively healthy lungs, without the application of a RM, higher PEEP levels mainly induce airway distention rather than improve alveolar ventilation.

Recently, we demonstrated that homogeneous ventilation by means of ITV agreed well with a PEEP level, with the highest dynamic compliance.20 We compared the whole dependent with the non-dependent lung region and found that the dependent lung region had the highest TIV at 12 cm H2O PEEP and decreased with each decremental PEEP step, indicating collapse in that region. At a PEEP level of 12 cm H2O the dependent and non-dependent lung regions were in balance. Above this PEEP the dependent region received most of the tidal volume, whereas below this PEEP the non-dependent region was predominantly ventilated. Thus EIT is the first device able to visualize collapse and hyperinflation of lung tissue at the bedside.

In an experimental study by Tusman and colleagues32 a RM followed by decremental PEEP trial from 24 to 0 cm H2O in steps of 2 cm H2O was performed, in eight lung lavaged pigs. They investigated the ability of Vcap to detect optimal PEEP, as compared with computed tomography scans (CT), and found that dynamic compliance, VDalv/VTalv and Pa-ETCO2 correlated best with the amount of non-aerated lung tissue as detected by CT-scans. Yang and colleagues33 performed a decremental PEEP trial on eight lung-lavaged piglets. After a RM they stepwisely reduced the PEEP from 20 cm H2O to 4 cm H2O in steps of 4 cm H2O. At PEEP levels below 16 cm H2O they found that VDalv/VTalv was well correlated to non-aerated and normally aerated lung tissue as assessed by CT-scans. In addition, they found that the lowest SIII value was closely related to best lung function. They concluded that VDalv/VTalv and SIII are best predictors for alveolar collapse or hyperinflation. Therefore, from these two studies it can be concluded that Vcap is a reliable tool to detect both collapse and hyperinflation of lung tissue, as confirmed by CT-scans, which is the golden standard to assess alveolar collapse or hyperinflation.

Maisch and colleagues34 performed an incremental and decremental PEEP trial in 20 anesthetized patients with healthy lungs, undergoing faciomaxillary surgery. During the PEEP trial, PEEP levels between 0 and 15 cm H2O were applied in PEEP steps of 5 cm H2O. They showed that after a RM physiological dead space was the lowest at 10 cm H2O PEEP, whereas static compliance of the respiratory system was the highest at that PEEP level. In addition, functional residual capacity and were insensitive parameters for detection of alveolar hyperinflation as they decreased with each PEEP step. Therefore, they concluded that physiological dead space and static compliance of the respiratory system, are suitable parameters for PEEP titration. Interestingly, we found that the PEEP level at which VDBohr/VT and VDEnghoff/VT significantly decreased (Table 2), suggesting a reduction in V/Q mismatch, agreed well with the PEEP level at which the inspired air was homogeneously distributed to the dependent and non-dependent lung regions, as measured by EIT (Figs 2 and 3). However, at lower PEEP levels, VDBohr/VT and VDEnghoff/VT keeps decreasing indicating that this parameter adds no additional information about ventilation homogeneity at lower PEEP. In addition, the exhaled CO2 per breath (VCO2,br) and the SnIII both showed that elimination of CO2 improved at lower PEEP levels (Table 2), but no optimum could be found. Therefore, in the present study design and study population, Vcap is not able to detect homogeneous ventilation.

Our finding in Vcap that PEEP mainly increases the airway-volume rather than improves alveolar ventilation is apparently in contradiction with the results of other studies published earlier.14,32,33 Lower PEEP levels cause a shift of the Vcap curve to the left (Fig. 4a), indicating increased airway dead space at higher PEEP levels. These opposing results could be explained by the fact that post-cardiac surgery patients have relatively healthy lungs. Although the patients in our study may have atelectasis, there is no question of surfactant depletion and we assume that the atelectasis is recruited without the need for high PEEP levels. In contrast, the previous studies used the lung-lavaged models with large amount of shunt area, which are recruitable at high PEEP levels. However, Nieman and colleagues35–41 found during in vivo microscopy in normal and surfactant deactivated pigs, during ventilation with tidal volumes of 6, 12 and 15 ml kg−1, that in normal lungs the alveolar area at end-inspiration and end-expiration (I-EΔ) did not differ between the three different tidal volumes, whereas in the surfactant deactivated lungs I-EΔ increased significantly at higher tidal volumes. In a next study35 they used different tidal volumes (6, 12, 15 ml kg−1) and PEEP levels (5, 10, 20 cm H2O) and found that I-EΔ did not change in normal lungs, whereas in surfactant deactivated lungs the alveolar size significantly increased, as compared with normal lungs with equal settings. From these studies it can be concluded that in normal lungs with stable alveoli, PEEP volume results in airway distention, whereas in ALI/ARDS lungs, PEEP keeps the alveoli open and stabilized. In addition, airway distention as a result of high PEEP might also explain why physiological dead space calculated according to Enghoff, increases at higher PEEP levels, whereas did not significantly differ during the different PEEP levels, except at ZEEP. This explains the absence of a change in SIII and the left shift of SII in the Vcap curves at decreasing PEEP levels in our patients.

There are limitations to this study. Firstly, we did not apply a RM before the PEEP reduction, in order to avoid serious deterioration of haemodynamics in the direct postoperative period. It has been shown that Vcap parameters after an RM are more sensitive to detect changes in CO2 elimination, as compared with PEEP trials without an RM.42,43 Secondly, EIT describes the ventilation distribution in a lung slice of approximately 5–10 cm thick.42,44 Therefore, the image obtained from the single cross-section does not represent the entire lung. In addition, PEEP increases results in changed chest size and intrathoracic blood volume. However, by using two large regions of interest, the corresponding lung tissue to the individual pixel is limited. The effect of changed intrathoracic blood volume is limited, as EIT is a hundred times more sensitive to impedance changes caused by aeration, as compared with impedance changes caused by the cardiac system.45–47 Thirdly, the time intervals of 5–10 min at each PEEP level might be too short to achieve a steady state for obtaining reliable data. However, a recent study showed that elimination of CO2 reached a new stable period within five min of a PEEP change.48 It is known that Vcap is influenced by both the cardiac system and the pulmonary system. In this study we did not perform cardiac output measurements. Therefore we cannot assess Vcap changes induced by reduced cardiac output at higher PEEP levels. However, we found no significant differences in bp and heart rate between PEEP 14 and ZEEP. Therefore, we assume that the influence of the change in cardiac output with different PEEP levels on dead space was not profound.

Conclusion

In postoperative cardiac patients with low shunt fractions, dead space calculations according to Bohr and Enghoff agreed well with EIT. EIT is able to detect the optimal PEEP level for equal distribution of inspired air, among the non-dependent and the dependent regions of the lungs. In contrast, VDalv/VTalv and SnIII were unable to detect this distribution. In addition, we found that in relatively healthy lungs, applying higher PEEP levels mainly induced airway distention rather than improvement of alveolar ventilation.

Authors' contributions

Study design/planning: P.B., D.G.

Study conduct: P.B., A.S., B.H., T.W.

Data analysis: P.B., A.S., B.H., T.W., D.H., D.G.

Writing paper: P.B., A.S., B.H., T.W., D.H., D.G.

Revising paper: all authors

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at British Journal of Anaesthesia online.

Declaration of interest

None declared.

Funding

Department of Adult Intensive Care, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Plotz FB, Slutsky AS, van Vught AJ, Heijnen CJ. Ventilator-induced lung injury and multiple system organ failure: a critical review of facts and hypotheses. Intensive Care Med 2004; 30: 1865–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Futier E, Constantin JM, Paugam-Burtz C et al. . A trial of intraoperative low-tidal-volume ventilation in abdominal surgery. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 428–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schultz MJ, Haitsma JJ, Slutsky AS, Gajic O. What tidal volumes should be used in patients without acute lung injury? Anesthesiology 2007; 106: 1226–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mead J, Takishima T, Leith D. Stress distribution in lungs: a model of pulmonary elasticity. J Appl Physiol 1970; 28: 596–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Protti A, Cressoni M, Santini A et al. . Lung stress and strain during mechanical ventilation: any safe threshold? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183: 1354–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Protti A, Andreis DT, Monti M et al. . Lung Stress and Strain During Mechanical Ventilation: Any Difference Between Statics and Dynamics?. Crit Care Med 2013; 41: 1046–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briel M, Meade M, Mercat A et al. . Higher vs lower positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2010; 303: 865–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Putensen C, Theuerkauf N, Zinserling J, Wrigge H, Pelosi P. Meta-analysis: ventilation strategies and outcomes of the acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute lung injury. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: 566–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cressoni M, Cadringher P, Chiurazzi C et al. . Lung inhomogeneity in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189: 149–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gattinoni L, Caironi P, Cressoni M et al. . Lung recruitment in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 1775–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suarez-Sipmann F, Bohm SH, Tusman G. Volumetric capnography: the time has come. Curr Opin Crit Care 2014; 20: 333–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kallet RH, Zhuo H, Liu KD, Calfee CS, Matthay MA. The Association Between Physiologic Dead-Space Fraction and Mortality in Subjects With ARDS Enrolled in a Prospective Multi-Center Clinical Trial. Respir Care 2014; 59: 1611–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tusman G, Groisman I, Fiolo FE et al. . Noninvasive monitoring of lung recruitment maneuvers in morbidly obese patients: the role of pulse oximetry and volumetric capnography. Anesth Analg 2014; 118: 137–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bohm SH, Maisch S, von SA et al. . The effects of lung recruitment on the Phase III slope of volumetric capnography in morbidly obese patients. Anesth Analg 2009; 109: 151–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fengmei G, Jin C, Songqiao L, Congshan Y, Yi Y. Dead space fraction changes during PEEP titration following lung recruitment in patients with ARDS. Respir Care 2012; 57: 1578–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frerichs I, Hinz J, Herrmann P et al. . Detection of local lung air content by electrical impedance tomography compared with electron beam CT. J Appl Physiol 2002; 93: 660–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meier T, Luepschen H, Karsten J et al. . Assessment of regional lung recruitment and derecruitment during a PEEP trial based on electrical impedance tomography. Intensive Care Med 2008; 34: 543–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Victorino JA, Borges JB, Okamoto VN et al. . Imbalances in regional lung ventilation: a validation study on electrical impedance tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 169: 791–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bikker IG, Blankman P, Specht P, Bakker J, Gommers D. Global and regional parameters to visualize the ‘best’ PEEP during a PEEP trial in a porcine model with and without acute lung injury. Minerva Anestesiol 2013; 79: 983–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blankman P, Hasan D, Groot JE, Gommers D. Detection of ‘best’ positive end-expiratory pressure derived from electrical impedance tomography parameters during a decremental positive end-expiratory pressure trial. Crit Care 2014; 18: R95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowhagen K, Lundin S, Stenqvist O. Regional intratidal gas distribution in acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome--assessed by electric impedance tomography. Minerva Anestesiol 2010; 76: 1024–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blankman P, Hasan D, van Mourik MS, Gommers D. Ventilation distribution measured with EIT at varying levels of pressure support and Neurally Adjusted Ventilatory Assist in patients with ALI. Intensive Care Med 2013; 39: 1057–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blankman P, van der Kreeft SM, Gommers D. Tidal ventilation distribution during pressure-controlled ventilation and pressure support ventilation in post-cardiac surgery patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2014; 58: 997–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bikker IG, Leonhardt S, Reis MD, Bakker J, Gommers D. Bedside measurement of changes in lung impedance to monitor alveolar ventilation in dependent and non-dependent parts by electrical impedance tomography during a positive end-expiratory pressure trial in mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients. Crit Care 2010; 14: R100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costa EL, Borges JB, Melo A et al. . Bedside estimation of recruitable alveolar collapse and hyperdistension by electrical impedance tomography. Intensive Care Med 2009; 35: 1132–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suter PM, Fairley B, Isenberg MD. Optimum end-expiratory airway pressure in patients with acute pulmonary failure. N Engl J Med 1975; 292: 284–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tusman G, Scandurra A, Bohm SH, Suarez-Sipmann F, Clara F. Model fitting of volumetric capnograms improves calculations of airway dead space and slope of phase III. J Clin Monit Comput 2009; 23: 197–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tusman G, Gogniat E, Bohm SH et al. . Reference values for volumetric capnography-derived non-invasive parameters in healthy individuals. J Clin Monit Comput 2013; 27: 281–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ream RS, Schreiner MS, Neff JD et al. . Volumetric capnography in children. Influence of growth on the alveolar plateau slope. Anesthesiology 1995; 82: 64–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fletcher R, Jonson B, Cumming G, Brew J. The concept of deadspace with special reference to the single breath test for carbon dioxide. Br J Anaesth 1981; 53: 77–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blankman P, van der Kreeft SM, Gommers D. Tidal ventilation distribution during pressure-controlled ventilation and pressure support ventilation in post-cardiac surgery patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2014; 58: 997–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tusman G, Suarez-Sipmann F, Bohm SH et al. . Monitoring dead space during recruitment and PEEP titration in an experimental model. Intensive Care Med 2006; 32: 1863–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Y, Huang Y, Tang R et al. . Optimization of positive end-expiratory pressure by volumetric capnography variables in lavage-induced acute lung injury. Respiration 2014; 87: 75–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maisch S, Reissmann H, Fuellekrug B et al. . Compliance and dead space fraction indicate an optimal level of positive end-expiratory pressure after recruitment in anesthetized patients. Anesth Analg 2008; 106: 175–81, table [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halter JM, Steinberg JM, Gatto LA et al. . Effect of positive end-expiratory pressure and tidal volume on lung injury induced by alveolar instability. Crit Care 2007; 11: R20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nieman GF, Bredenberg CE, Clark WR, West NR. Alveolar function following surfactant deactivation. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 1981; 51: 895–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schiller HJ, McCann UG, Carney DE, Gatto LA, Steinberg JM, Nieman GF. Altered alveolar mechanics in the acutely injured lung. Crit Care Med 2001; 29: 1049–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Halter JM, Steinberg JM, Schiller HJ et al. . Positive end-expiratory pressure after a recruitment maneuver prevents both alveolar collapse and recruitment/derecruitment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167: 1620–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schiller HJ, Steinberg J, Halter J et al. . Alveolar inflation during generation of a quasi-static pressure/volume curve in the acutely injured lung. Crit Care Med 2003; 31: 1126–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steinberg JM, Schiller HJ, Halter JM et al. . Alveolar instability causes early ventilator-induced lung injury independent of neutrophils. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 169: 57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steinberg J, Schiller HJ, Halter JM et al. . Tidal volume increases do not affect alveolar mechanics in normal lung but cause alveolar overdistension and exacerbate alveolar instability after surfactant deactivation. Crit Care Med 2002; 30: 2675–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Erlandsson K, Odenstedt H, Lundin S, Stenqvist O. Positive end-expiratory pressure optimization using electric impedance tomography in morbidly obese patients during laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2006; 50: 833–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tusman G, Bohm SH, Suarez-Sipmann F, Turchetto E. Alveolar recruitment improves ventilatory efficiency of the lungs during anesthesia. Can J Anaesth 2004; 51: 723–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindgren S, Odenstedt H, Olegard C, Sondergaard S, Lundin S, Stenqvist O. Regional lung derecruitment after endotracheal suction during volume- or pressure-controlled ventilation: a study using electric impedance tomography. Intensive Care Med 2007; 33: 172–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barber DC. A review of image reconstruction techniques for electrical impedance tomography. Med Phys 1989; 16: 162–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brenner D, Elliston C, Hall E, Berdon W. Estimated risks of radiation-induced fatal cancer from pediatric CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 176: 289–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Visser KR. Electric properties of flowing blood and impedance cardiography. Ann Biomed Eng 1989; 17: 463–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tusman G, Bohm SH, Suarez-Sipmann F, Scandurra A, Hedenstierna G. Lung recruitment and positive end-expiratory pressure have different effects on CO2 elimination in healthy and sick lungs. Anesth Analg 2010; 111: 968–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.