Abstract

Aims

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) from mice with monocrotaline (MCT)-induced pulmonary hypertension (PH) induce PH in healthy mice, and the exosomes (EXO) fraction of EVs from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can blunt the development of hypoxic PH. We sought to determine whether the EXO fraction of EVs is responsible for modulating pulmonary vascular responses and whether differences in EXO-miR content explains the differential effects of EXOs from MSCs and mice with MCT-PH.

Methods and results

Plasma, lung EVs from MCT-PH, and control mice were divided into EXO (exosome), microvesicle (MV) fractions and injected into healthy mice. EVs from MSCs were divided into EXO, MV fractions and injected into MCT-treated mice. PH was assessed by right ventricle-to-left ventricle + septum (RV/LV + S) ratio and pulmonary arterial wall thickness-to-diameter (WT/D) ratio. miR microarray analyses were also performed on all EXO populations. EXOs but not MVs from MCT-injured mice increased RV/LV + S, WT/D ratios in healthy mice. MSC-EXOs prevented any increase in RV/LV + S, WT/D ratios when given at the time of MCT injection and reversed the increase in these ratios when given after MCT administration. EXOs from MCT-injured mice and patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) contained increased levels of miRs-19b,-20a,-20b, and -145, whereas miRs isolated from MSC-EXOs had increased levels of anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative miRs including miRs-34a,-122,-124, and -127.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that circulating or MSC-EXOs may modulate pulmonary hypertensive effects based on their miR cargo. The ability of MSC-EXOs to reverse MCT-PH offers a promising potential target for new PAH therapies.

Keywords: Pulmonary hypertension, Exosomes, Extracellular vesicles, Mesenchymal stem cells, MicroRNA

1. Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rare disease that is characterized by vascular remodelling of the distal pulmonary arterial circulation. The remodelling seen in PAH includes both apoptosis and proliferation of pulmonary vascular endothelial cells, muscularization of distal pulmonary arterioles, deposition of extracellular matrix proteins, and perivascular inflammation.1,2 These myriad changes lead to a loss of peripheral arterioles and an obliterative vasculopathy in parts of the vascular bed that remain. As the disease progresses, pulmonary vascular resistance increases leading to right ventricular (RV) failure and death. Presently available medical therapies consist of vasorelaxant drugs with some degree of selectivity for the pulmonary circulation. These medications have improved functional capacity and delayed the time to clinical deterioration, but a cure for the disease will likely require an approach that halts or reverses the broad pulmonary vascular remodelling that occurs.

The cause of pulmonary vascular remodelling in PAH is not well understood. Altered synthesis and metabolism of endogenous pulmonary vasodilators, growth factors, and inflammatory pathways have been identified, but it remains unclear whether these abnormalities are responsible for initiating and propagating the disease or whether they merely represent altered cell signalling after the disease has developed. The numerous vascular abnormalities observed in PAH suggest that the disease is unlikely to be caused by a single event or even by a moderate number of defects. Rather, dysregulation of a broad array of signalling pathways involved in apoptosis, angiogenesis, and inflammation is likely needed to induce and maintain the pulmonary vascular changes that are seen.

MicroRNAs (miRs) are small non-coding RNAs that modulate the transcription of up to hundreds of genes at a time by binding to a common moiety in the promoter region and suppressing the translation of mRNA. Many of these miR species are known to regulate the transcription of integrated gene programs that are involved in vascular cell growth, apoptosis, and inflammation making them ideally suited to modulate the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension (PH). Recent studies have proposed a variety of miRs as key modulators of pulmonary vascular remodelling that may offer important therapeutic targets for treating PAH.3–5 However, it is unclear where these miR species derive from and how they are delivered to their target cells.

Two major pools of circulating miRs have been described. One includes miRs that are bound to the argonaute2 family of proteins that allow them to remain intact without being degraded by RNAses.6 The other major pool includes miRs that are transported in extracellular vesicles (EVs). EVs are cell-derived structures that contain cytoplasmic and cellular membrane components representative of the cells from which they were shed. They are generated spontaneously but also in response to exogenous stressors including hypoxia, shear stress, irradiation, chemotherapeutic agents, and cytokines.7 Several distinct sub-populations of EVs have been described in the literature including exosomes (EXOs), microparticles, ectosomes, microvesicles (MVs), membrane particles, and apoptotic vesicles.8 Included in their cargo are a number of proteins and nucleic acid species including small RNAs and miRs. Initially thought of as cellular debris, numerous studies have demonstrated that EVs act as vehicles for the intracellular transmission of RNA and protein species which directly impact recipient cell gene expression and cellular phenotype.9–13

Previously, we demonstrated that EVs isolated from the circulation or lungs of mice with monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension (MCT-PH) induce right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) and pulmonary vascular remodelling when injected in to healthy mice.14 However, others have shown that EVs isolated from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are capable of blunting the development of hypoxic PH in mice.15 MSCs have been increasingly recognized as a potential therapeutic approach to a variety of conditions including acute lung injury, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and PH. However, administration of MSC in these models has not been associated with any discernible increase in the number of MSC in the lung, suggesting that MSC act in some fashion other than direct tissue engraftment.

In the present study, we sought to determine which EV sub-population plays a regulatory role in the development and reversal of MCT-PH in mice and what differentiates EVs that induce disease from those that blunt it. We found that the EXO fraction of EVs isolated from mice with MCT-PH (MCT-PH EXOs) is responsible for inducing pulmonary hypertensive changes in healthy mice and that the EXO fraction of EVs isolated from MSC (MSC-EXOs) prevents and reverses PH in the same animal model. Furthermore, we found that MCT-PH EXOs contain increased levels of miRs that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of PAH, whereas MSC-EXOs contain increased levels of miRs that blunt angiogenesis, inhibit proliferation of neoplastic cells, and induce senescence of vascular SMCs and endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs). We also found that many of the miRs that were increased in MCT-PH EXOs were also increased in EXOs isolated from patients with idiopathic PAH (IPAH) compared with healthy volunteers and that EXO isolated from human MSCs were just as effective as EXOs from murine MSC in reversing MCT-PH in mice. Together, these findings suggest a prominent role of EXOs in mediating the pulmonary vascular remodelling seen in PH and point to a novel potential therapeutic approach for the treatment of PAH.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental animals

All mouse studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Rhode Island Hospital, CMTT#s 0090-10, 0211-08) and were performed to conform to NIH guidelines (Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals). Six- to eight-week-old male C57BL/6 mice were used for all studies and were euthanized via CO2 inhalation/cervical dislocation.

2.2. Isolation and culture of MSCs

Murine MSCs (mMSCs) were isolated and cultured as described by Zhu et al.16 Briefly, leg bones were removed from 10 mice and flushed with α-MEM (Hyclone) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine/10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) to remove haematopoietic stem cells. Prior to use, FBS was ultracentrifuged at 10 000 g for 1 h. Pelleted material was discarded, and the supernatant was ultracentrifuged at 100 000 g for 1 h. The supernatant, containing FBS depleted of EXOs, was then used for all tissue isolation or cell culture experiments. Bones were collagenase-digested, placed in plastic culture flasks with α-MEM/10% EXO-depleted FBS, and incubated at 37°C. Culture medium was changed (Day 3) to remove non-adherent cells, debris. On Day 5, bone chips and adherent cells were reseeded into new flasks and incubated at 37°C. Culture medium was changed every 48 h. Immunotyping characterization of cells occurred at Passage 4 confirming the presence of CD29+/CD44+/Sca-1+/CD31−/CD45−/CD86− adherent cells. Adipogenic, chondrogenic, and osteogenic differentiation assays were performed at Passage 5 confirming the differentiation capacity of cells into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes.

Human MSCs (hMSCs) used in these studies were purchased from Lonza. These cells were isolated from normal non-diabetic adult bone marrow withdrawn from bilateral punctures of the posterior iliac crests of multiple human donors. hMSCs were cultured as per manufacturer's instructions.

2.3. Isolation and characterization of MSC-derived EVs populations

MSC-EVs were isolated from cell-free culture media obtained at Passage 8 (Passage 5 for hMSCs). As MSCs grown using this protocol can be maintained for up to 10 passages, EVs isolated at this time are derived from true MSCs.16 Cells were removed by centrifugation (300 g, 10 min), and the supernatant was separated into three different fractions as follows: (i) MV fraction: cell-free culture media were ultracentrifuged at 10 000 g for 1 h followed by resuspension of the pelleted material in PBS; (ii) EXO fraction: the supernatant from the MV pellet was ultracentrifuged at 100 000 g for 1 h and the pelleted material was resuspended in PBS; and (iii) EV fraction: cell-free culture media were ultracentrifuged at 100 000 g for 1 h without the preceding 10 000 g ultracentrifugation step and the pelleted material, containing MVs and EXOs, was resuspended in PBS. The protein content of all fractions was determined by the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce). In addition, vesicle populations were characterized by EM, western blot, and NanoSight analysis.

2.4. PH induction studies using different EV populations from MCT-injured mice

Mice received injections of EVs, EXOs, or MVs, isolated from the lungs or plasma of MCT-injured or vehicle-injected mice. EVs, EXOs, or MVs were given at a dose of 25 µg in 100 µL of PBS via tail vein injection once daily for 3 days. Twenty-five micrograms of EVs, EXOs, and MVs were isolated from ∼2 to 4 × 106 cultured lungs cells and 150–300 µL of whole blood. Control mice received an equal volume of PBS. Mice were analysed 4 weeks later.

2.5. MCT injury prevention study using mMSC-EVs

Mice received weekly subcutaneous injections of MCT (600 mg/kg) or PBS (vehicle) for 4 weeks. Three hours after each injection, mice received either 25 µg of mMSC-EVs in 100 µL of PBS or an equal volume of PBS via tail vein injection. Twenty-five micrograms of EVs were isolated from ∼2 to 4 × 106 cultured mMSCs. Mice were analysed 1 week later (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1).

2.6. MCT injury reversal studies using MSC-EVs

Mice received weekly subcutaneous injections of MCT or PBS for 4 weeks. One week after the last series of injections, part of the group was sacrificed for analysis and the remainder received daily tail vein injections of mMSC-EVs or hMSC-EVs, 25 µg/day or an equal volume of PBS, for 3 days. Twenty-five micrograms of EVs were isolated from ∼2 to 4 × 106 cultured mMSCs or hMSCs. Mice were analysed 4 weeks later (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2).

In separate experiments, mice received daily tail vein injections of mMSC-EVs, murine lung cell-derived EVs (LEVs), or non-MSC bone marrow-derived cell EVs (lineage-depleted bone marrow cell EVs or Lin-EVs), 25 µg/day or an equal volume of PBS, for 3 days starting 1 week after the last series MCT or vehicle injections. Twenty-five micrograms of EVs were isolated from ∼2 to 4 × 106 cultured lung cells or Lin− cells. Mice were analysed 4 weeks later.

Also in separate experiments, mice received weekly subcutaneous injections of MCT or PBS for 4 weeks. One week after the last series of injections, part of the group was sacrificed for analysis, and the remainder received daily tail vein injections of mMSC-EVs, -EXOs or -MVs, 25 µg/day or an equal volume of PBS, for 3 days. Twenty-five micrograms of EVs, EXOs, and MVs were isolated from ∼2 to 4 × 106 cultured mMSCs. Mice were analysed 4 weeks later.

2.7. Lung histology

Lungs were inflated with 1.5 cc of 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, and the pulmonary circulation was flushed with 10 cc of PBS. Both were performed at a constant pressure (20 cm H2O). Right and left lungs were embedded separately in paraffin, and haematoxylin and eosin staining was performed on 5 µm sections from each paraffin block. Ten blood vessels (on end, diameters 20–50 μm) were analysed from the right and left lung of each mouse. The pulmonary vessel wall thickness-to-blood vessel wall diameter (WT/D) ratio was determined by measuring the thickness of the vessel wall (internal lamina-to-adventitia) and dividing by the intraluminal diameter (internal lamina-to-internal lamina).

2.8. Measurement of RV hypertrophy

The RV free wall was dissected off the interventricular septum and weighed wet. Measurements were expressed as the RV free wall-to-left ventricle + septum ratio (RV/LV + S).

2.9. miR microarray analysis

miRs isolated from the following EV populations: (i) mMSC-EXOs; (ii) Lin− EXOs; (iii) Plasma EXOs from MCT-injured mice; (iv) Plasma EXOs from vehicle-injected mice; (v) Plasma EXOs from human subjects with PAH, and (vi) Plasma EXOs from control subjects. Three independent samples were processed for each group analysed. Total RNA was measured for quantity and quality using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. Approximately 0.25–0.5% of the total RNA fraction extracted were miR species. Ten nanograms of total RNA per sample, isolated from 5 to 10 µg of EXOs, was used to amplify cDNA using the High Capacity cDNA transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, all equipment/reagents). cDNA pre-amplification reactions were performed using a pooled mixture of all primer assays and consisted of one 10 min cycle, 95°C; 14 cycles, 95°C, 15 s; one 4 min cycle, 60°C. RT–PCR reactions were performed in with the 7900HT Fast RT PCR System using 384-well TaqMan® Rodent and Human MicroRNA Array Cards. The 2−ΔΔCT method was used to calculate relative expression of each target miR,17 using snoRNA 202 (rodent array) and RNU6B (human array) as endogenous controls.

2.10. Statistical analysis

All analyses were run using SAS Software 9.4 (SAS Inc.) with the GLIMMIX procedure. Analyses for Figures 1 and 6 were accomplished using generalized estimating equations assuming a normal distribution with Sandwich estimation. All other analyses were examined using the general linear model (two-way ANOVA) using least squares estimation. Multiple comparisons were examined using Tukey corrections. Significance was established at the 0.05 level, and all interval estimates were calculated for 95% confidence. Data in Figures 1–6 are presented as mean values with 95% CIs.

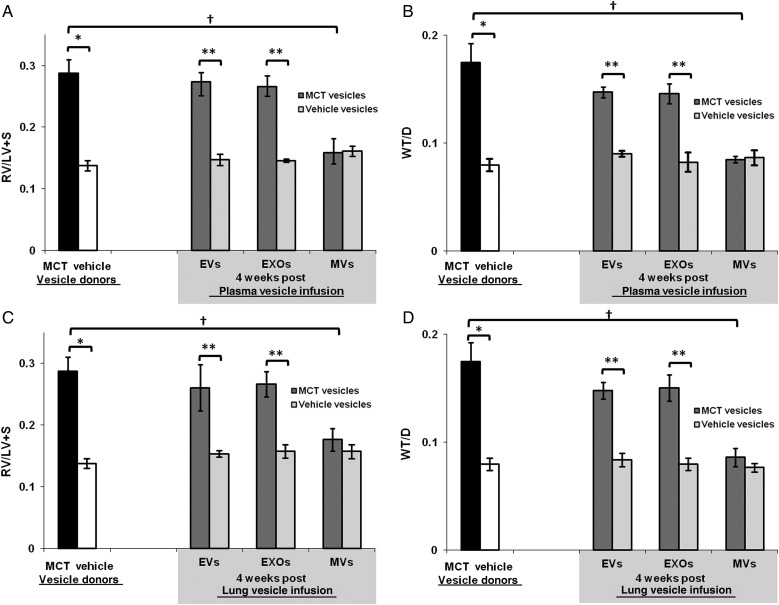

Figure 1.

EXOs from MCT-injured mice induce RV hypertrophy, pulmonary vascular remodeling. (A–D) RV/LV + S, WT/D ratios of MCT-injured (black bars) and vehicle-injected mice (white bars). Plasma and lung vesicles harvested from these mice were infused into healthy mice. RV/LV + S, WT/D ratios 4 weeks after healthy mice were infused with (A and B) plasma- or (C and D) lung EVs, -EXOs, or -MVs isolated from MCT-injured (dark grey bars), vehicle-injected (light grey bars) mice. n = 5 mice per group; *vs. vehicle-injected mice (P < 0.0001 for all comparisons), **vs. mice injected with vesicles from vehicle-injected mice (P < 0.0001 for all comparisons), †vs. MCT-injured mice (P < 0.0001 for all comparisons).

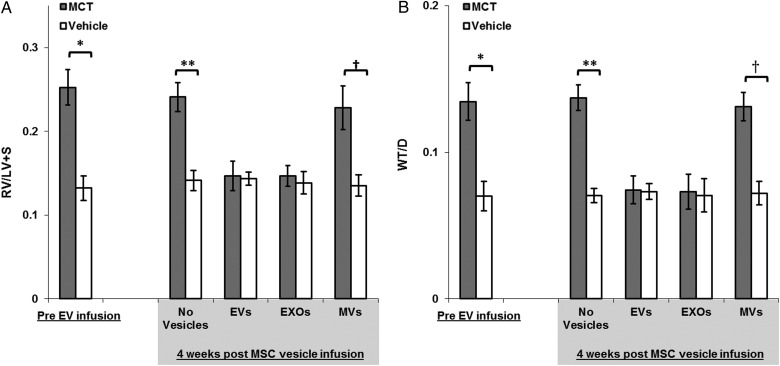

Figure 6.

Reversal of MCT-induced RV hypertrophy, pulmonary vascular remodelling with mMSC-EXOs. (A and B) RV/LV + S, WT/D ratios of MCT-injured (grey bars) and vehicle-injected mice (white bars) pre-EV infusion. Mice were then infused with mMSC-EVs, mMSC-EXOs, mMSC-MVs, or vehicle (no vesicles). RV/LV + S, WT/D ratios 4 weeks after MCT-injured (grey bars) or vehicle-injected (white bars) mice received EVs, EXOs, MVs, or vehicle. n = 5 mice per group; *vs. vehicle-injected mice (P < 0.001 for all comparisons); **vs. vehicle-injected mice treated with vehicle (P < 0.001 for all comparisons); †vs. vehicle-injected mice treated with mMSC-MVs (P < 0.001 for all comparisons).

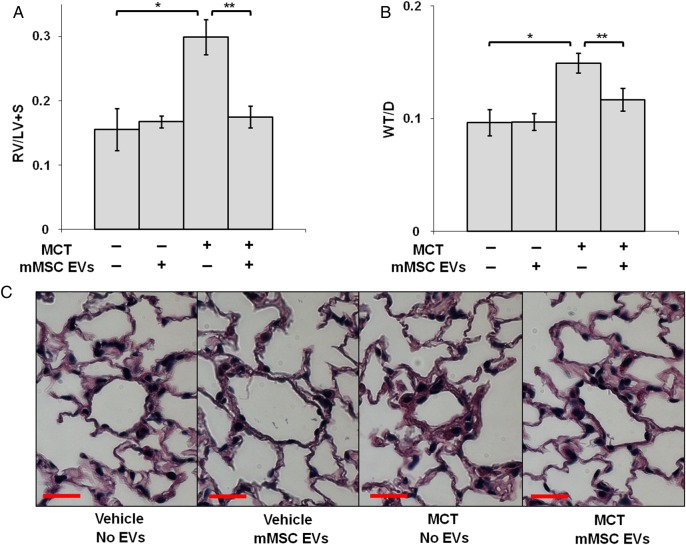

Figure 2.

Prevention of MCT-induced RV hypertrophy, pulmonary vascular remodelling with mMSC-EVs. (A) RV/LV + S, (B) WT/D ratios of MCT-injured or vehicle-injected mice that received concurrent mMSC-EV or vehicle infusions. n = 8 mice per group; *vs. vehicle-injected mice treated with vehicle (P < 0.0001 for all comparisons); **vs. MCT-injured mice treated with vehicle (P < 0.0001 RV/LV + S ratio, P = 0.0094 WT/D ratio). (C) Haematoxylin and eosin staining of lung sections from each group. Red bar = 20 µm.

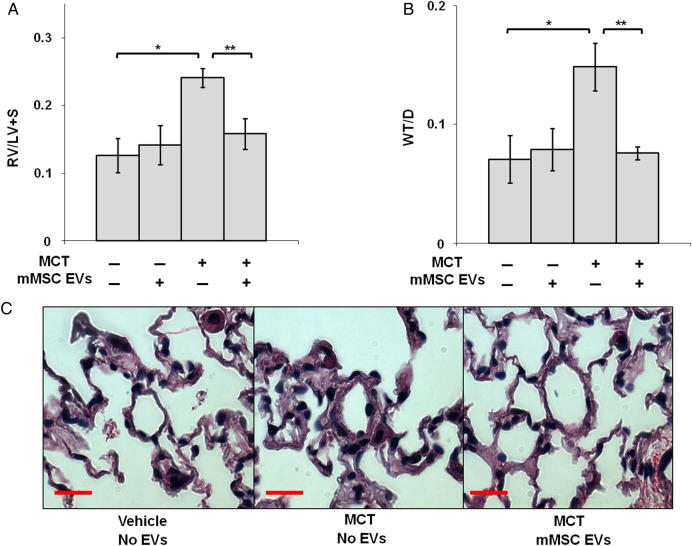

Figure 3.

Reversal of MCT-induced RV hypertrophy, pulmonary vascular remodelling with mMSC-EVs. (A) RV/LV + S, (B) WT/D ratios 4 weeks after MCT-injured or vehicle-injected mice received mMSC-EV or vehicle infusions. n = 10 mice per group; *vs. vehicle-injected mice treated with vehicle (P < 0.0001 for all comparisons); **vs. MCT-injured mice treated with vehicle (P < 0.0001 for all comparisons). (C) Haematoxylin and eosin staining of lung sections from each group. Red bar = 20 µm.

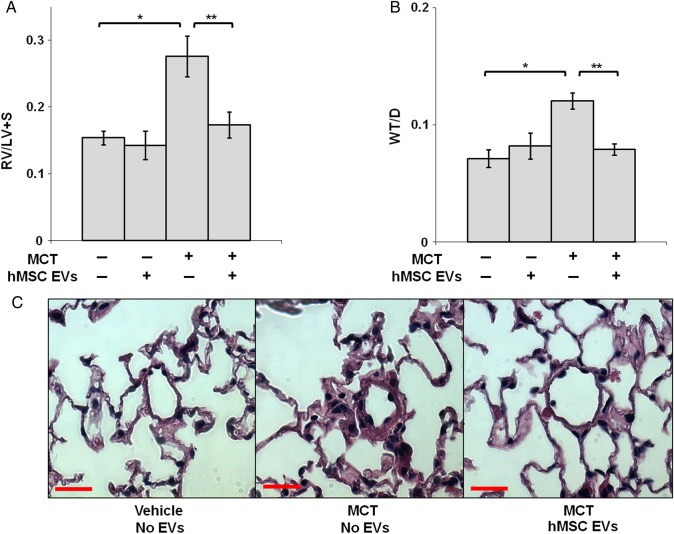

Figure 4.

Reversal of MCT-induced RV hypertrophy, pulmonary vascular remodelling with hMSC-EVs. (A) RV/LV + S, (B) WT/D ratios 4 weeks after MCT-injured or vehicle-injected mice received hMSC-EV or vehicle infusions. n = 5 mice per group; *vs. vehicle-injected mice treated with vehicle (P < 0.0001 for all comparisons); **vs. MCT-injured mice treated with vehicle (P < 0.0001 for all comparisons). (C) Haematoxylin and eosin staining of lung sections from each group. Red bar = 20 µm.

Figure 5.

EV populations that do not reverse MCT-induced RV hypertrophy, pulmonary vascular remodelling. (A and B) RV/LV + S, WT/D ratios of MCT-injured (grey bars) and vehicle-injected mice (white bars) pre-EV infusion. Mice were then infused with murine bone marrow-derived lineage-depleted cell EVs (Lin-EVs), murine lung EVs, or vehicle (no EVs). RV/LV + S, WT/D ratios 4 weeks after MCT-injured (grey bars) or vehicle-injected (white bars) mice received EV or vehicle infusions. n = 5 mice per group; *vs. vehicle-injected mice (P < 0.001 for all comparisons); **vs. vehicle-treated mice treated with vehicle (P < 0.001 for all comparisons).

3. Results

3.1. EXOs from mice with MCT-PH induce pulmonary hypertensive changes

In previous studies,16 we found that EVs isolated from the plasma or lung homogenates of mice with MCT-PH induced RV hypertrophy and pulmonary vascular remodelling in healthy mice, whereas EVs from control mice had no effect. The EVs used in those studies contained numerous vesicle sub-populations, including MVs and EXOs. To determine what fraction of the EVs obtained from plasma and lung homogenates in these experiments were responsible for the pathogenic effect, we conducted additional experiments in the present study in which EVs from mice with MCT-PH and normal control mice were separated into EXOs and MVs. Groups of healthy mice received tail vein injections of EVs, MVs, or EXOs isolated from the plasma or lungs of MCT-injured or control mice or an equal volume of PBS. Four weeks later, RV/LV + S and WT/D ratios were significantly higher in mice injected with plasma or lung EVs or EXOs from mice with MCT-PH compared with mice injected with PBS or EVs or EXOs that were isolated from control mice (vehicle-injected mice that did not have PH) (Figure 1). Injection of MVs isolated from the plasma or lungs of MCT-PH mice did not increase RV/LV + S or WT/D ratios in healthy mice (Figure 1).

3.2. mMSC-EVs prevent MCT-induced RV hypertrophy and pulmonary vascular remodelling

To determine whether MSC-EVs can attenuate the development of MCT-PH, mice were given weekly subcutaneous injections of MCT or vehicle for 4 weeks. After each injection, mice in both groups received 25 µg of mMSC-EVs or an equal volume of PBS via tail vein injection. Four weeks after the last series of injections, RV/LV + S and WT/D ratios were significantly higher in MCT-injured mice treated with PBS compared with control mice treated with PBS. However, there was no increase in RV/LV + S or WT/D ratios in MCT-injured mice treated with mMSC-EVs compared with control mice or MCT-injured mice treated with PBS (Figure 2).

3.3. mMSC-EVs and hMSC-EVs reverse MCT-induced RV hypertrophy and pulmonary vascular remodelling

We next sought to determine whether mMSC-EVs were capable of reversing pulmonary hypertensive changes once MCT-PH had already been established. In these experiments, groups of MCT-injured and vehicle-injected mice received daily tail vein injections of 25 µg of mMSC-EVs or hMSC-EVs or an equal volume of PBS (vehicle), for 3 days beginning 1 week after the last injection of MCT. Four weeks after the last EV injection, RV/LV + S and WT/D ratios were significantly lower in MCT-injured mice treated mMSC-EV than in MCT-injured mice that were treated with PBS and no different than RV/LV + S and WT/D ratios in mice that did not receive MCT (Figure 3). Similar findings were seen in MCT-injured mice treated with hMSC-EVs. Four weeks after the last injection, RV/LV + S and WT/D ratios were significantly lower in MCT-injured mice treated with hMSC-EV than in MCT-injured mice given PBS alone and no different than RV/LV + S and WT/D ratios in mice that did not receive MCT (Figure 4).

In additional experiments, MCT-injured mice were treated with LEVs and Lin-EVs isolated from healthy mice. Four weeks after EV injections, RV/LV + S and WT/D ratios in MCT-injured mice treated with these EVs were the same as MCT-injured mice treated with PBS alone (Figure 5).

3.4. The mMSC-EXO population reverses MCT-induced RV hypertrophy

To determine which fraction of the MSC-EVs was responsible for reversal of MCT-PH, groups of MCT-injured and vehicle-injected mice received daily tail vein injections of mMSC-EVs, mMSC-EXOs, mMSC-MVs, or an equal volume of PBS alone for 3 days following the final dose of MCT. Four weeks after the last series of EV injections, RV/LV + S and WT/D ratios were significantly lower in MCT-injured mice treated with mMSC-EXOs or mMSC-EVs than in mice injected with mMSC-MVs or PBS alone. RV/LV + S and WT/D ratios in MCT-injured mice treated with MSC-EXOs or -EVs were no different than in mice that were not treated with MCT (Figure 6).

3.5. Differential expression of EXO-based miRs

miR microarray analysis was performed on EXO-based miRs, and expression levels were compared with their control EXO population. miRs unique to or significantly up-regulated in (greater than two-fold) a given EXO population were recorded, and the following comparisons were made: (i) EXOs known to induce PH (MCT-injured mouse plasma EXOs) vs. their control population (vehicle-injected mouse plasma EXOs), (ii) EXOs known to reverse PH (mMSCs-EXOs) vs. their control population (Lin− marrow cell EXOs), and (iii) EXOs known to reverse PH vs. EXOs known to induce PH.

Compared with plasma EXOs isolated from vehicle-injected mouse, MCT-injured mouse plasma EXOs contained 19 miRs that were uniquely expressed or up-regulated, 140 miRs that were decreased or not expressed, and 221 miRs that were expressed at similar levels (see Supplementary material online, Figure S3). Compared with EXO isolated from Lin− bone marrow cells, mMSC-EXOs contained 65 miRs that were uniquely expressed or up-regulated, 147 miRs that were decreased or not expressed, and 168 that were expressed at similar levels (see Supplementary material online, Figure S3). Compared with EXOs isolated from the blood of mice with MCT-PH, mMSC-EXOs contained 44 miRs that were uniquely expressed or up-regulated, 115 miRs that were decreased or not expressed, and 221 that were expressed at similar levels (see Supplementary material online, Figure S3).

A similar analysis was performed on EXOs isolated from the plasma of human subjects with PAH and control subjects. Twenty-one miRs were found to be uniquely expressed or up-regulated in plasma EXOs from patients with IPAH vs. plasma EXOs from control subjects, including 11 that were also uniquely expressed or up-regulated in MCT-injured mouse plasma EXOs vs. vehicle-treated mouse plasma EXOs (Table 1).

Table 1.

miRs unique to/up-regulated in MCT-PH mouse EXOs and humans with IPAH vs. their control EXOs

| PH-inducing EXOsa vs. non-PH-inducing EXOsb (murine) | IPAH EXOs vs. control subject EXOs (human) |

|---|---|

| miR-let-7c | miR-let-7c |

| miR-16 | miR-let-7d |

| miR-19b | miR-16 |

| miR-20a | miR-18a |

| miR-20b | miR-19b |

| miR-21 | miR-20a |

| miR-93 | miR-20b |

| miR-101a | miR-27b |

| miR-133b | miR-30b |

| miR-145 | miR-30c |

| miR-146b | miR-125a-5p |

| miR-186 | miR-145 |

| miR-192 | miR-146b |

| miR-195 | miR-148a |

| miR-200b | miR-195 |

| miR-339-3p | miR-200b |

| miR-365 | miR-215 |

| miR-425 | miR-218 |

| miR-532-3p | miR-221 |

| miR-339-3p | |

| miR-365 |

aMCT-PH mouse plasma EXOs.

bVehicle-injected mouse plasma EXOs.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we found that the EXO fraction of EVs isolated from the plasma or lungs of mice with MCT-PH can induce increases in RV/LV + S and WT/D ratios in healthy mice and that EXOs isolated from MSCs can prevent the development of MCT-PH and reverse the pulmonary hypertensive changes seen in mice with established MCT-PH. These findings suggest that EXOs are capable of mediating both the development and the reversal of RV hypertrophy and pulmonary vascular remodelling depending on where they are derived from and strongly suggest that circulating EXOs play a pivotal role in modulating pulmonary hypertensive responses in this murine model of PH.

Others investigators have suggested that circulating EVs are increased in both preclinical and human forms of PH.18 We have previously shown that transfer of an unfractionated preparation of EVs obtained from the plasma or lungs of mice with MCT-PH to healthy mice caused the same type of RV hypertrophy and pulmonary vascular remodelling as occurs in MCT-PH, whereas injection of EVs isolated from the plasma or lungs of healthy mice had no effect.14 EVs isolated from plasma or tissue culture contain a variety of subcellular species including larger sized vesicles, which include MVs, smaller sized vesicles, which include EXOs, and cellular debris. Thus, it was unclear from our previous work what portion of the EV fraction was responsible for transferring the pulmonary hypertensive effects from diseased mice to healthy mice.

In the present study, we found that the pathogenic effect of EVs isolated from MCT-PH mice could be completely abrogated by removing the EXO fraction. Healthy mice given EXOs from the plasma or lungs of mice with MCT-PH developed RV hypertrophy and pulmonary vascular remodelling, whereas EVs from MCT-PH mice that had been depleted of EXOs had no pulmonary hypertensive effects. These findings demonstrate that EXOs are the EV species that modulate the pulmonary vascular responses seen in these experiments and strongly suggest that in this model of PH, EXOs may play an important role in disease progression once PH is established.

The MCT model of PH is characterized by endothelial apoptosis and perivascular inflammation. Release of EVs has been well described in a variety of cell types including vascular endothelial cells undergoing apoptosis. Although the cellular source of the EXO from MCT-PH mice that causes PH is uncertain, we found that EXOs obtained from cell-free lung conditioned media produced the same pulmonary hypertensive effects as EXOs isolated from plasma, whereas EVs obtained from other organs did not. In previous studies, we performed proteomic analyses of plasma- and lung-derived EVs from MCT-PH and vehicle-injected mice and found that EVs from both sources appear to be enriched with proteins specific to endothelial cells, platelets, erythroid cells, myeloid cells, and lymphoid cells.14 We also found that plasma and lung EVs isolated from MCT-PH mice had greater expression of endothelial cell markers compared with plasma and lung EVs from control mice.14 These findings strongly suggest that the plasma EXOs that are capable of inducing pulmonary hypertensive changes derive from the pulmonary vascular endothelium. The results from the present study support the hypothesis that pulmonary vascular endothelial cells release a unique population of EXOs that induce pulmonary hypertensive changes in the healthy lung. This may work as a positive feedback loop that serves to propagate vascular remodelling and may help to explain the difficulty in fully reversing MCT-PH once it has been established.

Interestingly, Lee et al.15 found that the protective effect of MSC infusion on hypoxic PH was also mediated by MSC-EXOs. In that study, intravenous delivery of MSC-EXOs given immediately before and 4 days after the start of exposure to hypoxia delayed the pulmonary influx of macrophages and blunted the development of RV hypertrophy and vascular remodelling. In the present study, we found that a similar strategy of administering MSC-EVs at the time of injury prevents the development of MCT-PH. MSC-EV infusion given immediately after each injection of MCT completely prevented MCT-induced increases in RV hypertrophy and pulmonary vessel wall thickness. More importantly, mice injected with MSC-EVs starting 1 week after the last dose of MCT had complete reversal of RV hypertrophy and pulmonary vascular wall thickness. In contrast, infusion of EVs isolated from other tissues or non-mesenchymal bone marrow cells had no effect on reversing pulmonary hypertensive changes. The beneficial effects of MSC-EVs were not limited to mMSCs as hMSC-EVs were just as effective at reversing MCT-PH as mMSC-EVs. In addition, we found that the EXO fraction of EVs and not the MV fraction was responsible for reversal of pulmonary hypertensive changes. These findings support those of Lee et al.15 and extend their earlier observations to another model of PH. In addition, the present study demonstrates that MSC-EXOs are capable of reversing as well as blunting an experimental model of PH. These findings further the therapeutic potential of EXOs in the treatment of clinical pulmonary vascular disease.

The mechanisms by which EXOs modulate pulmonary vascular and RV hypertrophic responses remain to be elucidated; however, numerous studies suggest that EXOs are effective vehicles for the intracellular delivery of miRs. The role of miRs in the pathogenesis of PH has generated considerable interest due to their ability to modulate the expression of numerous genes simultaneously. Over a dozen miRs have been reported to be up-regulated in animal models of PH and in patients with PAH, and several others have been found to be down-regulated.3–5,19 In the present study, we speculated that the differing effects of MCT-PH mouse EXOs and MSC-EXOs on pulmonary vascular remodelling could be explained by differences in the miRs species that they contained. We found 19 miRs that were uniquely expressed or up-regulated more than two-fold in EXOs from mice with MCT-PH compared with EXOs from healthy mice. Several of these miRs have been implicated in the pathogenesis of PH. Interestingly, many of the miRs that were up-regulated in EXOs from mice with MCT-PH were also increased in EXOs from patients with IPAH. In fact, out of the 19 miRs that were uniquely expressed or up-regulated greater than two-fold in EXOs from MCT-PH mice, 11 were found to be up-regulated more than two-fold in IPAH patients compared with healthy controls. Increased miRs common to EXOs from MCT-PH mice and IPAH patients include the miR-17–92 cluster, miR-21, and miR-145. The miR-17–92 cluster (which includes miRs-17, -18a, -19a, -20a, -19b-1, and -92-1) is a well-characterized family of miRs that is known to play important roles in modulating cellular proliferation and apoptosis.20 There has been considerable interest in the role of the miR-17–92 cluster in modulating pulmonary vascular remodelling, because BMPR2, the primary mediator of familial PH, has been shown to be a direct target of several members of this family, including miRs-17 and -20a.21 Point mutations in the BMPR2 gene have been identified in over 70% of cases of familial PH and in about a quarter of IPAH.22,23 Interestingly, protein levels of BMPR2 are depressed in patients with IPAH and in animal models of PH even in the presence of normal BMPR2 gene expression suggesting that miR inhibition of BMPR2 transcription may play an important role in the pathogenesis of PAH.22,23 More importantly, depletion of miR-20a using a targeted antagomir restores BMPR2 signalling and blunts the development of hypoxic PH, strongly suggesting that miR-20a is capable of inducing pulmonary vascular disease.24 Thus, miR-20a delivery to pulmonary vascular endothelial cells by circulating EXOs may play an important role in inducing or promoting PH.

miRs-21 and -145 have also been strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of PAH.25,26 Several studies suggest that miR-21 enhances vascular SMC proliferation and migration.26,27 miR-21 expression is increased by hypoxia, BMPR2 signalling, and IL-6 and is highly dysregulated in PAH.27,28 Whether or not miR-21 is capable of inducing PH is unclear. Antisense inhibitors of miR-21 have been shown to reduce pulmonary vascular remodelling in hypoxia.26 However, others have shown that miR-21 may protect against PH as miR-21-null mice have exaggerated pulmonary hypertensive responses.28 miR-145 is highly expressed in vascular SMCs and has been shown to promote a contractile phenotype.29 miR-145 expression is activated by TGF-β, BMP4, and hypoxia and has been found to be elevated in patients with PAH.30 Targeted disruption of the gene for miR-145 or antisense inhibition protects against the development of hypoxia-induced PH.30

In addition to miRs that are felt to be involved in the pathogenesis of PAH, nearly all of the miRs that were found to be up-regulated or uniquely expressed in MCT-PH mouse EXOs and IPAH patients fall into a category described by Hale et al.19 as hypoxamirs. Hypoxamirs are a subset of miRs that are increased in response to low oxygen tension. Although hypoxia has long been considered an important environmental stimulus of pulmonary vascular remodelling, the molecular and cell signalling mechanisms responsible for hypoxia-induced PH have been unclear. Recent studies strongly suggest that the miR species that are up-regulated in response to reduced oxygen tension are likely to play important roles in regulating the pulmonary vascular remodelling in response to hypoxia.19 Of the roughly 1400 distinct miRNA species that have been identified, ∼165 have been identified as hypoxamirs related to TGF/BMP signalling, inflammatory stimuli, and hypoxia.19 Virtually all of the miRs found to be up-regulated in EXOs from MCT-PH mice, and patients with IPAH are included in this category including miR-17–92 cluster, miR-21, and miR-145. Thus, the miRs that are increased in EXOs from mice and IPAH patients include many species that have been associated with the pathogenesis of PAH. Whether or not these miRs contribute to the development of PH or are increased as a result of PH will require additional studies. However, our findings that the EXOs that contain increased levels of these miRs induce PH when injected into healthy mice, whereas EXOs without increased levels of these miRs (EXOs isolated from control mice) do not, strongly suggests that one or more of these miR can induce pulmonary vascular remodelling.

Identifying miRs that are up-regulated during the development of PH may further our understanding of the pathogenesis of the disease. Furthermore, determining which miRs and their downstream targets are necessary for mediating the pathologic effect of MCT-PH EXOs could help to identify potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of PAH. In addition, a program or pattern of miR expression in circulating EXOs that is unique to pulmonary vascular remodelling could be used as a biomarker that could aid in the diagnosis and monitoring of PAH.

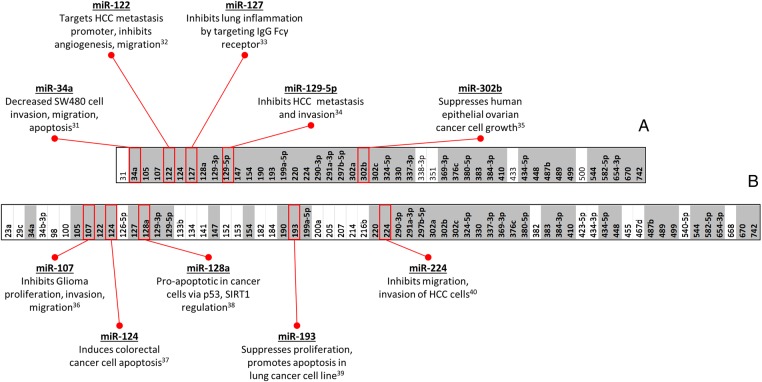

At the same time, a number of miRs were found to be increased in the MSC-EXOs that reversed PH in MCT-PH mice compared with non-MSC bone marrow stem/progenitor cells that had no effect. Many of these miRs (e.g. miRs-101a, -122, -193, -224, and -302b) have been found to induce apoptosis or suppress growth or migration of a variety of cancer cells (Figure 7, Refs 31–40). Although the effect of these miRs on pulmonary vascular remodelling has not been studied directly, their anti-proliferative properties on rapidly growing cell lines may explain in part, the ability of MSC-EXOs to reverse pulmonary hypertensive changes in MCT-PH mice. The increased expression of miR-124 in MSC-EXOs is particularly intriguing as recent studies have suggested that miR-124 down-regulation contributes to pulmonary vascular remodelling in hypoxic PH.41 Wang et al.41 found that miR-124 expression was significantly decreased in fibroblasts isolated from calves with hypoxic PH and from humans with severe IPAH. Furthermore, overexpression of miR-124 attenuated proliferation, migration, and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 expression of hypertensive fibroblasts. The investigators concluded that therapies directed at restoring miR-124 function have high potential for the treatment of PAH. Thus, it is possible that in the present study, reversal of pulmonary vascular remodelling in MCT-PH mice treated with MSC-EXOs was due in part to restoration of miR-124 expression in pulmonary fibroblasts.

Figure 7.

mMSC-derived EXO-based miRs. miRs unique to or up-regulated (greater than two-fold) in mMSC-EXOs (PH-reversing EXOs) compared with (A) EXO-based miRs from the plasma of MCT-injured mice (PH-inducing EXOs), (B) EXO-based miRs from Lin− cells (EXOs that neither reverse nor induce PH). miRs in bold font/highlighted in grey are common to both comparisons.

Finally, recent studies have suggested a role of miR-34a in mediating the senescence of EPCs, fibroblasts, and vascular SMCs and inhibiting angiogenesis.42 Considering the prominent role of EPCs and the proliferation of fibroblasts and vascular SMCs in pulmonary vascular remodelling, it is possible that the reversal of MCT-PH following injection of MSC-EXOs was due to transfer of EXO-based miR-34a to the bone marrow and pulmonary circulation.

In the only other study that we are aware of in which MSC-EXOs were used to blunt PH in mice,15 investigators also analysed differences in miR content between EXOs that blunted PH and those that did not and found increased expression of miRs-16, - 21,-199 a, and pre-let 7b. Although we found increased levels of the miR-199a family in MSC-EXO, we saw no differences in miR-16, 21, or pre-let-7b. However, non-mesenchymal bone marrow cell EXOs (Lin− bone marrow cell EXOs) were used as our control population, whereas, in the previous study, MSC-EXO content was compared with that of fibroblast EXOs.

There are several limitations to the findings of this study. First, the EXO and MV sub-populations used in our studies were separated using differential centrifugation. This seperative technique does not yield pure sub-populations of vesicles.43,44 Although the mean size of all EXOs used in these studies is within the 30–100 nm size range described in the EXO literature,8 EM and NanoSight analysis revealed that vesicles in the MV size range (100–1000 nm) are detected in these preparations. Similarly, sub-100 nm vesicles contaminate MV populations used in these studies. In spite of limitations presented by differential centrifugation, there is no consensus on a ‘gold standard’ method to isolate EVs. The International Society of Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) has recently published a position statement that outlines minimal experimental requirements for definition of EVs, which includes the presence of transmembrane proteins such as tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81).45 Tetraspanins are typically present in EXOs but absent in MVs.8 By western blot analysis, we show that all of the EVs (which include EXOs and MVs) and EXOs used in these studies are positive for both CD63 and CD81 and some are weakly positive for CD9. Conversely, none of the MVs used in these studies are positive for CD63 but some are weakly positive for either CD9 or CD81 (see Supplementary material online, Figures S4–S8). These data indicate that although the EXO and MV populations used in these studies are not pure, they are certainly enriched with EXOs and/or MVs. Most importantly, we demonstrate that despite this impurity, EXO and MV sub-populations have vastly different effects when infused into mice.

It is also possible that non-EV miRNA may have pelleted with large proteins and may have contributed to the observations reported in this manuscript. We feel that this is unlikely as the EV pellets were washed thoroughly prior to use. In addition, miRNAs bound to large proteins are not anticipated to remain intact during lung cell culture and are therefore unlikely to have contributed to induction or reversal of PH in these studies. Furthermore, we have previously demonstrated that plasma and cell culture media conditioned by lung isolated from mice with MCT-PH that had been depleted of EVs by ultracentrifugation do not induce PH when infused into healthy mice.14

FBS that was used during tissue isolation and cell culture provides an additional source of EVs that could affect the outcome of our studies. However, the vast majority of EVs was depleted by ultracentrifugation of FBS prior to use. Although, it is possible that a trivial amount of FBS-based EVs may have contaminated EV populations used in these studies. As all EVs used in these studies were prepared with the same EV-depleted FBS and some EV populations had a biological effect (induction or reversal or PH) and others did not, it is unlikely that EVs from bovine serum confound the results. Furthermore, miR microarray analysis using the murine and human array cards performed on EV-depleted bovine serum did not reveal the presence of any miR species. Therefore, the miR species reported in these studies were not contaminated with bovine-based miRs.

In summary, we show that injection of EXOs can induce or reverse MCT-induced PH in mice depending on their source of origin. EXOs that induce PH appear to derive from pulmonary vascular endothelial cells once PH has been established and have increased levels of miRs that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of PH, whereas EXOs that reverse PH appear to be unique to MSCs and have increased expression of miRs that induce anti-proliferative, apoptotic, or senescent effects on a variety of hyperproliferative cells including EPCs, fibroblast, and vascular SMCs. Considering these findings, we propose that circulating EXOs released from pulmonary vascular endothelial cells and MSCs play important roles in modulating pulmonary vascular remodelling. As such, EXOs represent promising targets that could be used for the development of new therapeutic strategies in the treatment of PAH.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Cardiovascular Research online.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Funding

This project was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM103468 P.J.Q., HL088328 J.R.K., GM103652 J.M.A.).

References

- 1.Rabinovitch M, Guignabert C, Humbert M, Nicolls MR. Inflammation and immunity in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Res 2014;115:165–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathew R. Pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension: a case for caveolin-1 and cell membrane integrity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2014;306:H15–H25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bienertova-Vasku J, Novak J, Vasku A. MicroRNAs in pulmonary arterial hypertension: pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. J Am Soc Hypertens 2015;9:221–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guignabert C, Tu L, Girerd B, Ricard N, Huertas A, Montani D, Humbert M. New molecular targets of pulmonary vascular remodeling in pulmonary arterial hypertension: importance of endothelial communication. Chest 2015;147:529–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant JS, White K, MacLean MR, Baker AH. MicroRNAs in pulmonary arterial remodeling. Cell Mol Life Sci 2013;70:4479–4494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arroyo JD, Chevillet JR, Kroh EM, Ruf IK, Pritchard CC, Gibson DF et al. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108:5003–5008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ratajczak J, Wysoczynski M, Hayek F, Janowska-Wieczorek A, Ratajczak MZ. Membrane-derived microvesicles: important and underappreciated mediators of cell-to-cell communication. Leukemia 2006;20:1487–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Théry C, Ostrowski M, Segura E. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nature Rev Immunol 2009;9:581–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deregibus MC, Cantaluppi V, Calogero R, Lo Iacono M, Tetta C, Biancone L. Endothelial progenitor cell derived microvesicles activate an angiogenic program in endothelial cells by a horizontal transfer of mRNA. Blood 2007;110:2440–2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baj-Krzyworzeka M, Szatanek R, Weglarczyk K, Baran J, Urbanowicz B, Branski P. Tumor-derived microvesicles carry several surface determinants and mRNA of tumor cells and transfer some of these determinants to monocytes. Cancer Immunol Imunother 2006;55:808–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rozmyslowicz T, Majka M, Kijowski J, Murphy SL, Conover DO, Poncz M. Platelet- and megakaryocyte-derived microparticles transfer CXCR4 receptor to CXCR4-null cells and make them susceptible to infection by X4-HIV. AIDS 2003;17:33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aliotta JM, Sanchez-Guijo FM, Dooner GJ, Johnson KW, Dooner MS, Greer KA et al. Alteration of marrow cell gene expression, protein production, and engraftment into lung by lung-derived microvesicles: a novel mechanism for phenotype modulation. Stem Cells 2007;25:2245–2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aliotta JM, Pereira M, Johnson KW, de Paz N, Dooner MS, Puente N et al. Microvesicle entry into marrow cells mediates tissue-specific changes in mRNA by direct delivery of mRNA and induction of transcription. Exp Hematol 2010;38:233–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aliotta JM, Pereira M, Amaral A, Sorokina A, Igbinoba Z, Hasslinger A et al. Induction of pulmonary hypertensive changes by extracellular vesicles from monocrotaline-treated mice. Cardiovasc Res 2013;100:354–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee C, Mitsialis SA, Aslam M, Vitali SH, Vergadi E, Konstantinou G et al. Exosomes mediate the cytoprotective action of mesenchymal stromal cells on hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 2012;126:2601–2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu H, Guo ZK, Jiang XX, Li H, Wang XY, Yao HY et al. A protocol for isolation and culture of mesenchymal stem cells from mouse compact bone. Nat Protoc 2010;5:550–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−delta delta C(T)) method. Methods 2001;25:402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amabile N, Guignabert C, Montani D, Yeghiazarians Y, Boulanger CM, Humbert M. Cellular microparticles in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2013;42:272–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hale AE, White K, Chan SY. Hypoxamirs in pulmonary hypertension: breathing new life into pulmonary vascular research. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2012;2:200–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mendell JT. miRiad roles for the miR-17-92 cluster in development and disease. Cell 2008;133:217–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brock M, Trenkmann M, Gay RE, Michel BA, Gay S, Fischler M et al. Interleukin-6 modulates the expression of the bone morphogenic protein receptor type II through a novel STAT3-microRNA cluster 17/92 pathway. Circ Res 2009;104:1184–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Machado R, Aldred M, James V, Harrison R, Patel B, Schwalbe E et al. Mutations of the TGF-beta type II receptor BMPR2 in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Human Mut 2006;27:121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomson J, Machado R, Pauciulo M, Morgan N, Humbert M, Elliott G et al. Sporadic primary pulmonary hypertension is associated with germline mutations of the gene encoding BMPR-II, a receptor member of the TGF-beta family. J Med Gen 2000;37:741–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brock M, Samillan VJ, Trenkmann M, Schwarzwald C, Ulrich S, Gay RE et al. AntagomiR directed against miR-20a restores functional BMPR2 signalling and prevents vascular remodelling in hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J 2014;35:3203–3211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White K, Loscalzo J, Chan SY. Holding our breath: the emerging and anticipated roles of microRNA in pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ 2012;2:278–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang S, Banerjee S, Freitas Ad, Cui H, Xie N, Abraham E et al. miR-21 regulates chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2012;302:L521–L529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ji R, Cheng Y, Yue J, Yang J, Liu X, Chen H et al. MicroRNA expression signature and antisense-mediated depletion reveal an essential role of MicroRNA in vascular neointimal lesion formation. Circ Res 2007;100:1579–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parikh VN, Jin RC, Rabello S, Gulbahce N, White K, Hale A et al. MicroRNA-21 integrates pathogenic signaling to control pulmonary hypertension: results of a network bioinformatics approach. Circulation 2012;125:1520–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis-Dusenbery BN, Chan MC, Reno KE, Weisman AS, Layne MD, Lagna G et al. Down-regulation of Kruppel-like factor-4 (KLF4) by microRNA-143/145 is critical for modulation of vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype by transforming growth factor-beta and bone morphogenetic protein 4. J Biol Chem 2011;286:28097–28110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caruso P, Dempsie Y, Stevens HC, McDonald RA, Long L, Lu R et al. A role for miR-145 in pulmonary arterial hypertension: evidence from mouse models and patient samples. Circ Res 2012;111:290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai M, Du G, Shi R, Yao J, Yang G, Wei Y et al. MiR-34a inhibits migration and invasion by regulating the SIRT1/p53 pathway in human SW480 cells. Mol Med Rep 2015;11:3301–3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta P, Cairns MJ, Saksena NK. Regulation of gene expression by microRNA in HCV infection and HCV-mediated hepatocellular carcinoma. Virol J 2014;11:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie T, Liang J, Liu N, Wang Q, Li Y, Noble PW et al. MicroRNA-127 inhibits lung inflammation by targeting IgG Fcγ receptor I. J Immunol 2012;188:2437–2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma N, Chen F, Shen SL, Chen W, Chen LZ, Su Q et al. MicroRNA-129-5p inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell metastasis and invasion via targeting ETS1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015;461:618–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ge T, Yin M, Yang M, Liu T, Lou G. MicroRNA-302b suppresses human epithelial ovarian cancer cell growth by targeting RUNX1. Cell Physiol Biochem 2014;34:2209–2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen L, Li ZY, Xu SY, Zhang XJ, Zhang Y, Luo K et al. Upregulation of miR-107 inhibits glioma angiogenesis and VEGF expression. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2016;36:113–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun Y, Zhao X, Luo M, Zhou Y, Ren W, Wu K et al. The pro-apoptotic role of the regulatory feedback loop between miR-124 and PKM1/HNF4α in colorectal cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci 2014;15:4318–4332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adlakha YK, Saini N. miR-128 exerts pro-apoptotic effect in a p53 transcription-dependent and -independent manner via PUMA-Bak axis. Cell Death Dis 2013;4:e542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang J, Yang B, Han L, Li X, Tao H, Zhang S et al. Demethylation of miR-9-3 and miR-193a genes suppresses proliferation and promotes apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Cell Physiol Biochem 2013;32:1707–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li H, Li Y, Liu D, Sun H, Liu J. miR-224 is critical for celastrol-induced inhibition of migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 2013;32:448–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang D, Zhang H, Li M, Frid MG, Flockton AR, McKeon BA et al. MicroRNA-124 controls the proliferative, migratory, and inflammatory phenotype of pulmonary vascular fibroblasts. Circ Res 2014;114:67–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao T, Li J, Chen AF. MicroRNA-34a induces endothelial progenitor cell senescence and impedes its angiogenesis via suppressing silent information regulator 1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2010;299:E110–E116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Witwer KW, Buzás EI, Bemis LT, Bora A, Lässer C, Lötvall J et al. Standardization of sample collection, isolation and analysis methods in extracellular vesicle research. J Extracell Vesicles 2013;2; doi:10.3402/jev.v2i0.20360. eCollection 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Deun J, Mestdagh P, Sormunen R, Cocquyt V, Vermaelen K, Vandesompele J et al. The impact of disparate isolation methods for extracellular vesicles on downstream RNA profiling. J Extracell Vesicles 2014;3; doi:10.3402/jev.v3.24858. eCollection 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lötvall J, Hill AF, Hochberg F, Buzás EI, Di Vizio D, Gardiner C et al. Minimal experimental requirements for definition of extracellular vesicles and their functions: a position statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles 2014;3:26913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]