Highlights

-

•

Eosinophilic cystitis is a disease of unknown aetiology, however there is an association with a history of allergies and atopy.

-

•

Common presentations are urinary frequency, dysuria, haematuria, and suprapubic pain, leading to diagnosis of less sinister urinary causes such as urinary tract infections.

-

•

Natural history is difficult to predict, varying from acute self-resolving cases to chronic debilitating conditions requiring hospital admissions and radical interventions.

-

•

It is difficult to distinguish from other forms of cystitis and biopsy is necessary for diagnosis.

-

•

Treatment can vary from medical to operative intervention, or a combination of both.

Keywords: Haematuria, Eosinophilic cystitis, Bladder biopsy, Urinary tract infection, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Eosinophilic cystitis is a rare inflammatory condition of the bladder that can cause haematuria. The aetiology is unknown and clinical presentation is difficult to distinguish from other causes of haematuria. Diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy. In this case, a patient with haematuria is diagnosed with eosinohpilic cystitis after presenting to hospital. He was commenced on antibiotics for a presumed urinary tract infection with no resolution of haematuria and symptoms. After diagnosis he was commenced on treatment with resolution of symptoms.

Case presentation

A 73-year-old male presents with first episode of haematuria. He was initially diagnosed with a urinary tract infection and commenced on antibiotics with no resolution. After further investigations including a cystoscopy and bladder biopsy, he was diagnosed with eosinophilic cystitis. He was treated with steroids improving his symptoms.

Conclusion

Eosinophilic cystitis is a rare disease of the bladder which is difficult to distinguish from other causes of haematuria, and is often misdiagnosed. Bladder biopsy is necessary for diagnosis. Early diagnosis is important, and it is through a combination of non-operative and operative interventions such as biopsy. Natural history is difficult to predict as it is difficult to determine is a patient will have a benign course with resolution with or without treatment, or result in a chronic course which may result in bladder damage and renal failure. This case highlights the importance of investigating haematuria that is unresponsive to initial empiric treatment such as antibiotics. It is important to refer to a Urologist for further investigation to rule out a sinister cause, but to also obtain a diagnosis, leading to definitive treatment.

1. Introduction

Eosinophilic cystitis is a relatively rare inflammatory condition of the bladder [1]. The aetiology is unknown, but it has been associated in patients with allergies and atopy [2]. Patients commonly present with urinary frequency, dysuria, haematuria, and suprapubic pain [3] which may lead to a diagnosis of a urinary tract infection. It is difficult to distinguish eosinophilic cystitis from other forms of cystitis. On cystoscopy, raised velvety, polypoid, oedematous lesions are usually noted [1], [2], [4], but to confirm diagnosis, a biopsy is required. In this case, a patient with haematuria is diagnosed with eosinohpilic cystitis after presenting to hospital. Prior to this he was treated with antibiotics for a presumed urinary tract infection with no resolution of haematuria.

2. Case report

A 73-year-old male presented to hospital with a one day history of haematuria, dysuria, and frequency. This was his first occurrence of haematuria and he was treated with antibiotics by his general practitioner for a presumed urinary tract infection.

On examination he was afebrile, and haemodynamically stable. He was tender in the suprapubic area. He was passing frank haematuria with some clots. Bladder scan showed low post void residuals. Remainder of examination including rectal exam were unremarkable.

Blood tests showed an elevated C-reactive protein of 121 mg/L (Normal Range <5 mg/L). Haemoglobin, white cell count, and coagulation studies were normal. Urinalysis showed blood, leucocytes, nitrites, and protein. He was initially diagnosed with a urinary tract infection and commenced on intravenous antibiotics. A 20 French 3-way catheter was inserted and bladder irrigation was performed. Computed Tomography (CT) intravenous pyelogram showed a thickened bladder wall with no focal lesion. There was small amount of stranding at the distal left ureter, and the prostate was not significantly enlarged.

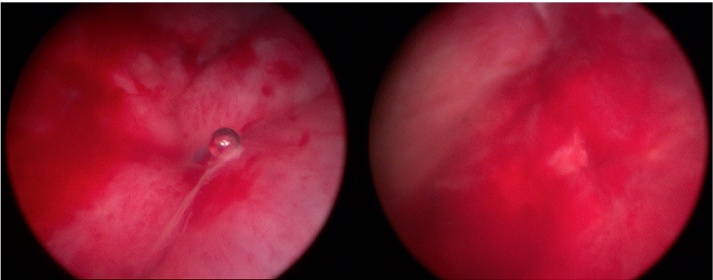

He eventually underwent a cystoscopy which found areas of patchy cystitis (Fig. 1) which were biopsied. There were no obvious lesions. Cytology of bladder washings showed no malignant cells. The bladder biopsies showed lamina propria with moderate inflammatory infiltrate rich in eosinophils and some lymphocytes suggestive of eosinophilic cystitis.

Fig. 1.

Cystoscopy found areas of patchy cystitis which were biopsied to confirm diagnosis.

Post-operative recovery was unremarkable, and after consultations with the Immunology team, he was commenced on prednisone. His urine cleared with treatment and repeat urine cultures showed no growth. He was discharged on prednisone. On subsequent follow up four weeks later the patient was well with no further episodes of haematuria. His prednisone was being weaned under the supervision of Immunologists.

3. Discussion

Eosinophilic cystitis is a relatively rare inflammatory condition of the bladder first reported by Brown and Palubinskas in 1960 [1], [4]. Since then there have been at most 200 cases reported in the literature. It is more common in adults, affecting men and women equally, however in children there is a slight male predominance [3]. The aetiology is unknown, but eosinophilic cystitis has been associated in patients with allergies and atopy [2]. Charcot-Leyden crystals, which are often encountered with other eosinophilic disorders and asthma, have also been reported [5]. An underlying dysfunction of the immune system has also been suggested due to reported cases of eosinophilic cystitis in patients with celiac disease [6]. In this study by Popescu et al. [6] they also found further associations with lupus anticoagulant, BK virus, and Antibacterial and Proteus mirabilis infections. Other associations include urinary tract infections [7], [8], and transitional cell carcinoma [1].

As shown by this case, eosinophilic cystitis commonly presents with urinary frequency, dysuria, haematuria, and suprapubic pain. Less commonly there may be nocturia and urinary retention [3], with the latter being more frequently reported in women and children [9]. Non-genitourinary symptoms, although rare, include gastrointestinal symptoms (vomiting, diarrhoea), and skin rashes [10], [11]. Physical examination, which is usually unremarkable, may find suprapubic tenderness as found in this case or lower abdominal mass as reported in some cases [12], [13], [14].

Investigations may show proteinuria and microscopic haematuria on urinalysis, however urine cultures are usually negative [3]. Eosinophiluria, which was not detected, is rare, as eosinophils are rapidly degraded or there is little mucosal shedding from the urothelium [15]. Presence of eosinophils is not diagnostic, as it is present in other renal and urological conditions. In blood tests, eosinophilia may be useful, however, it is found in approximately 50% of patients with a history of allergy or atopy.

Radiologically, variable thickening of bladder wall, from diffuse thickening to mass formation on ultrasound may be shown depending on the stage of eosinophilic cystitis [16]. Hydronephrosis, and bladder and ureteral filling defects, which were noted in some studies [9], [15], were not shown in this case. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and cystogram have also been used in eosinophilic cystitis patients with bladder masses in other studies, but there were no characteristic appearances [3].

It is difficult to distinguish eosinophilic cystitis from other forms of cystitis or bladder malignancy from cystoscopy. Raised velvety, polypoid, oedematous lesions are usually noted [1], [2], but to confirm diagnosis of eosinophilic cystitis, a biopsy is required. Histopathologically, there is transmural inflammation predominantly with eosinophils, with inflammation and oedema more intense in the lamina propria [17]. In this case, patches of erythema were found and biopsied, showing multiple levels of oedematous bladder, with lamina propria containing moderate inflammatory infiltrate rich in eosinophils. Lymphocytes were also noted. The histology can also be classified into the acute or chronic phase [16], [17]. The acute phase exhibits tissue eosinophilia, mucosal oedema, hyperaemia, and muscle necrosis. In the chronic phase, eosinophilia is not as prevalent, with variable chronic inflammation, and prominent scarring. In this context, the acute phase was found in the patient.

The chronicity and recurrence is difficult to predict given the variable natural history of eosinophilic cystitis. Most will have a benign course with resolution with or without treatment, whereas some become chronic leading to bladder damage and renal failure. Subequently, there may be a need for long-term monitoring with relevant blood and urine tests, imaging, and occasional cystoscopy [13], [17] to ensure other causes such as urothelial cancers are not the cause. Because of its rarity, there are no standardised treatment protocols. However, there have been algorithms described [17] where the precipitating factor(s) such as concurrent UTI or medication are removed if identified. If no precipitant is found, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and anti-histamines have been recommended, followed by corticosteroids as second line, and cyclosporine-A and azathioprine as third line if there is no resolution. Modifications can be made such as adding antibiotics, if an infection is found. If medical management fails, then operative intervention may be indicated ranging from diathermy to resection of bladder lesion to radical procedures such as cystectomy.

4. Conclusion

Eosinophilic cystitis is a disease for which aetiology is unknown. It may be precipitated or associated with other systemic or local conditions, making it difficult to distinguish from other urological conditions. In this case it was misdiagnosed as a urinary tract infection. Clinical assessment may be unremarkable, and biopsy is necessary to diagnose it. Once diagnosed, treatment is by a combination of medications and operative intervention. However, management may be modified by co-existing conditions, and the extent of effects on the bladder and upper tract. Natural history is difficult to predict and long-term follow up may be warranted to ensure that more sinister cause such as cancer is not being masked.

This case highlights the importance of investigating haematuria, a common presentation, that is unresponsive to antibiotic therapy. It is important to refer to a Urologist for further investigation. This will help rule out a sinister cause, but to also obtain a diagnosis, leading to definitive treatment, and prevent progression to a chronic disabling disease.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests or relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.

Funding

There are no sources of funding to be declared or acknowledged.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval not required.

Author contributions

Daniel Chia − Single author: concept, case report, design, writing of paper, obtaining image.

Consent

Informed consent has been provided by the patient for this case report and accompanying image with guarantee of confidentiality.

Guarantor

Daniel Chia.

References

- 1.Brown E.W. Eosinophilic granuloma of the bladder. J. Urol. 1960;83:665–668. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)65773-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hellstrom H.R., Davis B.K., Shonnard J.W. Eosinophilic cystitis. A study of 16 cases. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1979;72(5):777–784. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/72.5.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van den Ouden D. Diagnosis and management of eosinophilic cystitis: a pooled analysis of 135 cases. Eur. Urol. 2000;37(4):386–394. doi: 10.1159/000020183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palubinskas A.J. Eosinophilic cystitis: case report of eosinophilic infiltration of the urinary bladder. Radiology. 1960;75:589–591. doi: 10.1148/75.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamada T., Taguchi H. Clinical study of interstitial cystitis. 1-(2) The etiological consideration of 4 cases of interstitial cystitis with advanced contracted bladder. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 1984;75(5):795–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Popescu O.E., Landas S.K., Haas G.P. The spectrum of eosinophilic cystitis in males: case series and literature review. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2009;133(2):289–294. doi: 10.5858/133.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstein M. Eosinophilic cystitis. J. Urol. 1971;106(6):854–857. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)61417-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perlmutter A.D., Edlow J.B., Kevy S.V. Toxocara antibodies in eosinophilic cystitis. J. Pediatr. 1968;73(3):340–344. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(68)80110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van den Ouden D., van Kaam N., Eland D. Eosinophilic cystitis presenting as urinary retention. Urol. Int. 2001;66(1):22–26. doi: 10.1159/000056557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gregg J.A., Utz D.C. Eosinophilic cystitis associated with eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1974;49(3):185–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inglis J.A., Tolley D.A., Grigor K.M. Allergy to mitomycin C complicating topical administration for urothelial cancer. Br. J. Urol. 1987;59(6):547–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1987.tb04874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vetter V. Case of the month: a 2-year-old girl with urinary stasis and a bladder mass. Tumor-forming eosinophilic cystitis. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1995;154(11):935–936. doi: 10.1007/BF01957510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thijssen A., Gerridzen R.G. Eosinophilic cystitis presenting as invasive bladder cancer: comments on pathogenesis and management. J. Urol. 1990;144(4):977–999. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39638-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salman M. Eosinophilic cystitis simulating invasive bladder cancer: a real diagnostic challenge. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2006;38(3–4):545–548. doi: 10.1007/s11255-006-0103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itano N.M., Malek R.S. Eosinophilic cystitis in adults. J. Urol. 2001;165(3):805–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leibovitch I. Ultrasonographic detection and control of eosinophilic cystitis. Abdom. Imaging. 1994;19(3):270–271. doi: 10.1007/BF00203525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teegavarapu P.S. Eosinophilic cystitis and its management. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2005;59(3):356–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2004.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]