Abstract

Background

Dirofilaria repens and D. immitis are filarioid helminths with domestic and wild canids as main hosts and mosquitoes as vectors. Both species are known to cause zoonotic diseases, primarily pulmonary (D. immitis), ocular (D. repens), and subcutaneous (D. repens) dirofilariosis. Both D. immitis and D. repens are known as invasive species, and their distribution seems associated with climate change. Until very recently, both species were known to be nonendemic in Austria.

Methodology and Principal Findings

Metadata on introduced and possibly autochthonous cases of infection with Dirofilaria sp. in dogs and humans in Austria are analysed, together with analyses of mosquito populations from Austria in ongoing studies.

In Austria, most cases of Dirofilaria sp. in humans (30 cases of D. repens—six ocular and 24 subcutaneous) and dogs (approximately 50 cases—both D. immitis and D. repens) were most likely imported. However, occasionally infections with D. repens were discussed to be autochthonous (one human case and seven in dogs). The introduction of D. repens to Austria was confirmed very recently, as the parasite was detected in Burgenland (eastern Austria) for the first time in mosquito vectors during a surveillance program. For D. immitis, this could not be confirmed yet, but data from Germany suggest that the successful establishment of this nematode species in Austria is a credible scenario for the near future.

Conclusions

The first findings of D. repens in mosquito vectors indicate that D. repens presumably invaded in eastern Austria. Climate analyses from central Europe indicate that D. immitis also has the capacity to establish itself in the lowland regions of Austria, given that both canid and culicid hosts are present.

Introduction

Various vector-borne helminths are prevalent in Europe, including those transmitted by mosquitoes, such as Dirofilaria repens and D. immitis (Spirurida onchocercidae) (Table 1) [1]. The most important definitive hosts of D. repens are dogs, but the parasite can also infect wild carnivores like red foxes and wolves as well as cats and humans [2]. It is the causative agent of subcutaneous and ocular dirofilariosis. The distribution of D. repens is limited to the Old World, with highly prevalent areas (prevalences in dogs of >10%) in southern and eastern Europe, Asia Minor, central Asia, and Sri Lanka [3]. More than 1,500 cases of human subcutaneous or ocular dirofilariosis caused by this pathogen have been documented worldwide [3–5]. However, the estimated number of unreported cases is probably much higher [6]. Compared to D. immitis, the infestation with D. repens is less severe, with subcutaneous nodules that can be excised surgically.

Table 1. Comparison of Dirofilaria repens and D. immitis.

| Dirofilaria repens | Dirofilaria immitis—canine heartworm |

|---|---|

| • Canine and feline subcutaneous dirofilariosis | • Canine and feline cardiopulmonary dirofilariosis |

| • Zoonotic pathogen—human subcutaneous and ocular dirofilariosis | • Zoonotic pathogen—human pulmonary and ocular dirofilariosis |

| • Poor mammalian host specificity, with Canidae and Felidae as final hosts | • Poor mammalian host specificity, with Canidae and Felidae as final hosts |

| • Human—less suitable hosts | • Human—less suitable hosts |

| • Wild mammalian hosts: foxes | • Wild mammalian hosts: foxes, jackals, wolves, and pet ferrets |

| • Distribution: limited to Old World—southern and eastern Europe, Asia Minor, central Asia, and Sri Lanka | • Distribution: temperate, tropical, and subtropical areas of the world (Europe: main distribution in Mediterranean regions) |

D. immitis is responsible for canine and feline cardiopulmonary dirofilariosis [7]. Canine cardiopulmonary dirofilariasis, or heartworm disease, is a potentially life-threatening disease caused by adult D. immitis filariae [7]. Besides dogs, cats, ferrets, and wild carnivores (e.g., foxes, jackals, and wolves) may also serve as definite hosts of D. immitis but are asymptomatic in most cases [8]. Cats are generally more resistant to adult Dirofilaria, showing no or only nonspecific clinical signs [3].

As a zoonotic agent, D. immitis is the causative of human pulmonary dirofilariasis, but this parasite was recently also associated with ocular dirofilariasis [3,6]. However, humans are less suitable hosts, and the parasite usually cannot complete its life cycle. It induces local inflammation and granuloma formation in its human host without reaching maturity. D. immitis is distributed in temperate, tropical, and subtropical areas of the world. In Europe, the main distribution is located in Mediterranean regions, where high prevalences in dogs are observed, and in several areas, both D. repens and D. immitis coexist (e.g., [4]). In untreated dogs, heartworm prevalence rates ranging from 50% to 80% were reported in the Po Valley area in Italy (reviewed in [7]). Thirty-three cases of human pulmonary dirofilariosis had been documented in Europe by 2012, but as with D. repens, the true number of cases is assumed to be considerably higher.

In central Europe (including Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Liechtenstein, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Switzerland; definition of central Europe according to the World Fact Book: https://www.cia.gov/Library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2144.html), the first cases of D. immitis were described in four dogs in Switzerland in 1995 [9]. The first potential autochthonous findings of D. repens north of the Alpine Arc were documented in 11 clinically asymptomatic dogs from the south of Switzerland in 1998 [10]. D. repens and D. immitis have been documented more frequently in recent years, and autochthonous findings in dogs as well as mosquitoes are reported in new areas where both filarioid species were not known as endemic before [3,7,11]. By now (with the exception of Liechtenstein), both parasites have been reported in all countries neighboring Austria (Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Italy, and Switzerland) [3,7,11–17], and it is obvious that D. repens was documented in most central European areas prior to D. immitis.

Within this article, the authors describe the findings of imported and (potentially) autochthonous findings of D. repens and D. immitis in dogs, humans, and mosquitoes in Austria.

Methods

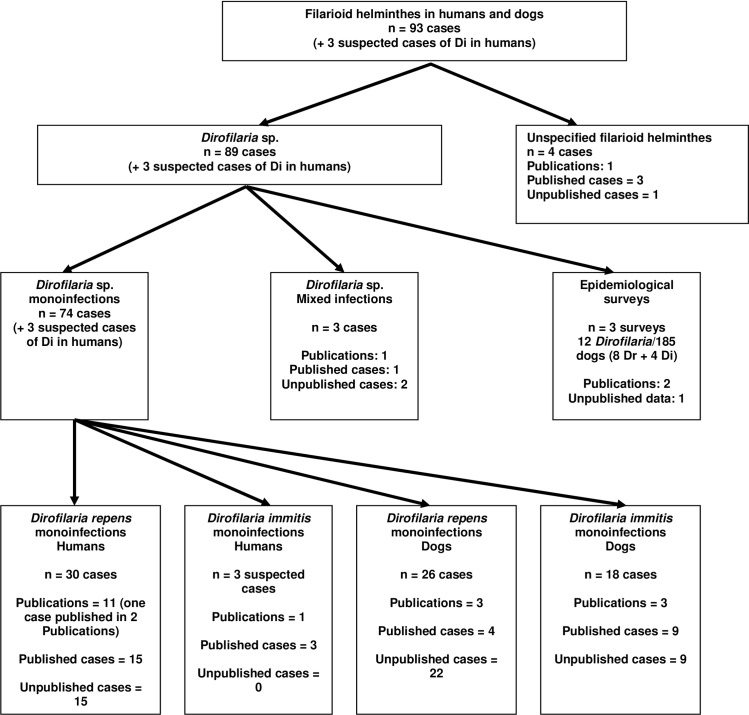

Published as well as unpublished cases of imported and autochthonous documentations of D. repens and D. immitis in dogs (definite hosts), humans (accidental hosts), and mosquitoes (vectors) in Austria are summarized (Fig 1). Published cases were examined using electronically available databases (NCBI, Scopus, Google Scholar) with the keywords “Dirofilaria” and “Austria.” Literature published in German was examined in the same way. Furthermore, unpublished cases were examined in electronic patient databases for Dirofilaria spp. (dogs: University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna; humans: Medical University of Vienna).

Fig 1. Flow chart (Di = Dirofilaria immitis).

Epidemiology of Dirofilaria spp. in Austria

Human Dirofilariosis in Austria

D. repens

Since 1978, 30 cases of human dirofilariosis caused by D. repens were reported in Austria, 16 (53%) in male patients and 14 (47%) in females (Table 2). Of these, 24 (80%) were subcutaneous infections and six (20%) ocular lesions. All patients presented clinical symptoms (appearance of skin nodes or wandering skin pain). Twenty-seven patients reported travel activity to at least one country known to be endemic for D. repens prior to infection. Fifty-three percent of all patients had been to the Mediterranean region, 13% to Hungary, and 27% overseas. About 30% of these infections were estimated to have been acquired in neighboring countries of Austria.

Table 2. Documented human Dirofilaria cases in Austria.

Dr: Dirofilaria repens; Di: Dirofilaria immitis; f: female; m: male; +: positive;–: negative; nd: not determined; His: Histology; Ser: Serology; maf: microfilariae (adult stage); mif: microfilariae (first larval stage); Eos: eosinophils; IgE: immunoglobulin E; Dv: Dipetalonema viteae antigen.

| Number | Year | Sex | Age | Pathology and/or Organ | Diagnosis | Geographical Anamnesis | Reference (if published) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1978 | f | 39 | hip, upper leg, knee | His: Dr (maf); Ser: Di–; IgE: 100 IU | Greece | Bardach et al. 1981[25] |

| 2 | 1989 | f | 27 | upper eyelid | His: Dr (maf); Ser: Di – | East Asia | Lammerhuber et al. 1989 [26] |

| 3 | 1992 | m | 36 | head (occipital) | His: Dr (maf) | Hungary, Greece, Italy | Auer 2004 [19] |

| 4 | 1995 | m | 44 | linea axillaris anterior (right) | His: Dr (maf) | Bahrain, Greece | Schuller-Petrovic et al. 1996 [27] |

| 5 | 1995 | m | 45 | lower leg (left) | His: Dr (mif) | nd | Bischof et al. 2003[28] |

| 6 | 1996 | m | 35 | epididymis | His: Dr (maf); Eos: 10%; Ser: Di +, Dr: + | Italy, Portugal | Auer et al. 1997 [29] |

| 7 | 1998 | f | 61 | orbital cavity | His: Dr (maf); Ser: Di – | Italy, Greece | Braun et al. 1999 [30] Groell et al. 1999 [31] |

| 8 | 1997 | f | 23 | shoulder | His: Dr (maf); Ser: Dv – | Bosnia | Auer et al. 2004 [19] |

| 9 | 1998 | m | 23 | right inguinal lymph nodes | His: Dr (maf); Ser: Di +, Dr +; Eos: 8% | Slovenia, Spain, Albania | Auer et al. 2004 [19] |

| 10 | 1998 | f | 48 | left chest, left axillary region | His: Dr (maf); Ser: Di + | Spain, Greece (Korfu) | Auer et al. 2004 [19] |

| 11 | 1998 | m | 43 | sacral | His: Dr (maf); Ser: Di + | Malta, Portugal, Italy (Sardinia) | Auer et al. 2004 [19] |

| 12 | 1999 | m | 4 | neck, back | Ser: Dr +; IgE: >1,000 IU; Eos: 10% | Italy | a |

| 13 | 2000 | m | 59 | right cheek | Ser: Dr +; IgE: 1,000 IU | nd | a |

| 14 | 2000 | f | 37 | right chest | His: Dr (maf); Ser: Dr + | Turkey, Spain | Auer et al. 2004 [19] |

| 15 | 2001 | m | 11 | inguinal lymphoma | Ser: Dr +, Di + | Indonesia (Bali) | a |

| 16 | 2001 | f | 60 | eye | His: worm not specified; Ser: + | nd | a |

| 17 | 2002 | m | 42 | upper extremity | His: Dr (maf); Eos: 6%; Ser: Dr +, Di + | Ethiopia, Ghana | a |

| 18 | 2003 | m | 61 | skin (wandering knot) | Ser: Dr–, Di + | Peru | a |

| 19 | 2003 | m | 54 | inguinal hernia | Ser: Dr +, Di + | nd | a |

| 20 | 2006 | f | 34 | palm | His: Dr (maf); PCR Dr; Ser: Dr +, Di - | Austria (Nickelsdorf, Burgenland) | Auer and Susani (2008) [18] |

| 21 | 2008 | f | 62 | cheek, oral mucosa | His: Dr (maf); PCR Dr | Hungary | a |

| 22 | 2009 | m | 61 | epididymis | His: Dr (maf); PCR Dr; Eos: 9% | Namibia | a |

| 23 | 2009 | f | 53 | right chest | His: Dr (maf); PCR Dr | Italy | Böckle et al. 2010 [32] |

| 24 | 2011 | f | 46 | eye (subconjunctival) | His: Dr (maf); PCR Dr | Bosnia | Ritter et al. 2012 [33] |

| 25 | 2011 | f | 65 | lumbar region | His: Dr (maf); PCR Dr | East Asia, Sri Lanka, India | a |

| 26 | 2011 | f | 49 | head (temporal) | His: Dr (maf) | Croatia, Serbia | a |

| 27 | 2012 | m | 53 | orbital cavity | His: Dr (maf); PCR Dr | Italy, Hungary, Croatia | a |

| 28 | 2012 | f | 39 | eye, migrating worm | His: Dr (maf) | India | a |

| 29 | 2014 | m | 75 | umbilical hernia | His: Dr (maf); PCR Dr | Hungary | a |

| 30 | 2014 | m | 50 | inguinal hernia | His: Dr (maf); PCR Dr | Greece | a |

aUnpublished patient data archived at the Medical University Vienna.

Only one human case of subcutaneous dirofilariosis was discussed as autochthonous acquired infection [18]. In September 2006, a 34-year-old border police officer from Nickelsdorf (Burgenland) presented a “tumor” 1 cm in diameter on the right palm of her hand after a mosquito bite. Histology and PCR were positive for D. repens and gave a negative result for D. immitis. Although the woman mentioned that she had never left Austria at geographical anamnesis, her occupation at the border to Hungary raised questions about the exact location where the infection was acquired.

D. immitis

Three suspected cases of human pulmonary dirofilariosis cases caused by D. immitis have been observed in Austria so far [19]. Patients presented pulmonary symptoms and were positive for D. immitis at serology. Because of the location in the lung, no invasive biopsies were conducted to confirm the presence of the parasite.

Dirofilaria Infections in Dogs in Austria

D. repens

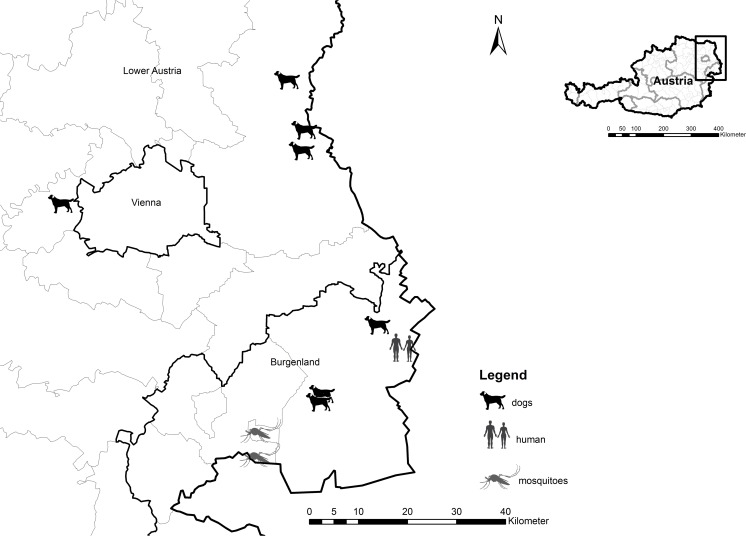

Overall, D. repens was detected in 37 dogs in Austria (Table 3). Excluding epidemiological surveys and mixed infections with D. immitis, 26 dogs presented monoinfections. Ten (38%) dogs were female and 16 were male (62%). In only five cases (19%) of the monoinfections did symptoms like skin nodules lead to the diagnosis of dirofilariosis. In all other cases, the pathogens were found incidentally or during travel screening. Fifteen (58%) of the dogs infected with D. repens (including mixed infections with D. immitis) had previous travel activity to countries neighboring Austria known to be endemic for D. repens (Hungary, Slovakia, or Germany). Seven (27%) of the monoinfections were reported in Austrian dogs whose travel activity remained unclear. However, an epidemiological study conducted in eastern Austria documented the findings of microfilariae of D. repens in one of eight dogs in Gänserndorf (Lower Austria) and six of 90 dogs in Neusiedl (Burgenland) by PCR and Knott test [20]. All potentially autochthonous cases (with no reported time spent abroad) were reported from eastern Austria (Lower Austria and Burgenland) only (Fig 2). With the exception of one case in Gablitz (west of Vienna), all of those cases were documented at the border areas to Slovakia and Hungary.

Table 3. Documented cases of Dirofilaria repens and Dirofilaria immitis in dogs in Austria.

+: positive;–: negative; nd: not determined; His: Histology; Ser: Serology; Maf: microfilariae (adult stage); mif: microfilariae (first larval stage) in blood, if not specified otherwise; Eos: eosinophils; IgE: immunoglobulin E; Ag-ELISA: SNAP Canine Heartworm Antigen Test Kit (IDEXX Laboratories).

| Number | Year | Sex (neutered) | Age | Breed | Symptoms and/or Reason for examination | Diagnosis | Geographical Anamnesis | Therapy | Reference (if published) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. repens | |||||||||

| 1 | before 2001 | f (n) | 4 | mongrel | subcutaneous nodule | Maf +; mif + | Greece | – | Leschnik et al. (2008) [34] |

| 2 | before 2001 | f (n) | 1 | Kuvasz crossbreed | hematuria,subcutaneous nodules (after primary diagnosis) | mif + in urine | Hungary | + | Kleiter et al. (2001) [35] |

| 3 | 2002 | f (n) | 11.5 | mongrel | incidental finding, tumor cytology | mif + | Hungary | – | a |

| 4 | 2004 | m | 2 | Dachshund | incidental finding, hematology | mif +; PCR +; Ag-ELISA – | Hungary | + | Leschnik et al. (2008) [34] |

| 5 | 2007 | f (n) | 8 | mongrel | conjunctivitis, swelling of the lower eye lid | Maf; mif +; Eos: 11% | Austria (Zurndorf, Burgenland) | + | a |

| 6 | 2008 | m | >3 | mongrel | incidental finding | PCR + | Hungary | – | a |

| 7 | 2008 | m | >3 | German Shorthaired Pointer | incidental finding | PCR + | Hungary, lives in district Neusiedl | – | b |

| 8 | 2008 | f | <3 | German Wirehaired Pointer | incidental finding | PCR + | Slovakia, lives in district Neusiedl | – | b |

| 9 | 2008 | f | >3 | Large Munsterlander | incidental finding | PCR + | Germany, lives in district Neusiedl | – | b |

| 10 | 2008 | f | >3 | Golden Retriever | incidental finding | PCR + | Austria (Podersdorf; Burgenland) | – | b |

| 11 | 2008 | m | >3 | Labrador Retriever | incidental finding | PCR + | Austria (Podersdorf; Burgenland), lives in district Neusiedl | – | b |

| 12 | 2008 | m | 7 | Wirehaired Dachshund | incidental finding | PCR + | Austria (Oberweiden; Gänserndorf), lives in district Gänserndorf | unclear | b |

| 13 | 2008 | m | 10 | German Wirehaired Pointer | incidental finding | PCR + | Austria (Zwerndorf; Gänserndorf), lives in district Gänserndorf | – | b |

| 14 | 2008 | m | 8 | Hanoverian Tracking Hound | incidental finding | PCR + | Hungary, lives in district Gänserndorf | – | b |

| 15 | 2008 | m | 6 | WireHaired Dachshund | incidental finding | PCR + | Slovakia, lives in district Gänserndorf | – | b |

| 16 | 2008 | f | 4 | Labrador Retriever | incidental finding | PCR + | Hungary, lives in district Gänserndorf | – | b |

| 17 | 2008–2010 | f | 6 | unknown | subcutaneous mandibular cyst | Maf; PCR + | Austria (Gablitz, Lower Austria)—exported to Germany | nd | Pantchev et al. (2011) [36] |

| 18 | 2012 | m (n) | 3 | mongrel | incidental finding, blood | mif +; PCR +; Ag-ELISA – | Slovakia | + | a |

| 19 | 2013 | m (n) | 7 | mongrel | incidental finding, tumor, cytology | mif +; PCR + | Slovakia | – | a |

| 20 | 2013 | m | 3 | mongrel | incidental finding, blood | mif +; PCR +; Ag-ELISA – | Romania | + | a |

| 21 | 2013 | m (n) | 6 | Golden Retriever | incidental finding, tumor, cytology | mif +; PCR +; Ag-ELISA – | Austria (Ebenthal/Lower Austria) | + | a |

| 22 | 2013 | f (n) | 5 | Newfoundland dog | incidental finding, tumor, cytology | mif +; PCR + | Hungary | + | a |

| 23 | 2013 | m (n) | 2 | mongrel | incidental finding, blood | mif +; PCR +; Ag-ELISA – | Croatia | + | a |

| 24 | 2014 | m (n) | 5 | Magyar Vizsla | incidental finding, tumor, cytology | mif + | Hungary | + | a |

| 25 | 2014 | m (n) | 3 | mongrel | incidental finding, subcutaneous nodule | mif +; PCR–; Ag-ELISA – | unclear | – | a |

| 26 | unclear | m (n) | 5 | mongrel | subcutaneous nodule | Maf; mif + | Hungary | + | a |

| D. immitis | |||||||||

| 1 | 1985 | m | 4 | Doberman | section | Two Maf in atrium cordis | former Yugoslavia, Italy, Greece, Turkey, France (Corsica) | – | Hinaidy et al. (1987) [37] |

| 2 | 1987 | nd | nd | Beagle | nd | nd | Japan, Saudi Arabia | nd | Löwenstein et al. (1988) [38] |

| 3 | 1987 | nd | nd | Rottweiler | nd | nd | Italy | nd | Löwenstein et al. (1988) [38] |

| 4 | 1988 | f | 4 | German Shepherd | necropsybloody expectoration, apathy, cough, dyspnea, inappetence, ascites | Approx. 40 Maf in right heart chamber and arteria pulmonalis | Italy | – | Löwenstein et al. (1988) [38] |

| 5 | before 2001 | m (n) | 5 | Spaniel | travel screening | Ag-ELISA +; mif + | Spain | – | Leschnik et al. (2008) [34] |

| 6 | before 2001 | f (n) | 6 | crossbreed | travel screening | Ag-ELISA +; mif + | Greece | – | Leschnik et al. (2008) [34] |

| 7 | before 2001 | f (n) | 3.5 | Greyhound | travel screening | Ag-ELISA +; mif + | Spain | – | Leschnik et al. (2008) [34] |

| 8 | 2001 | f (n) | 5 | crossbreed | travel screening | Ag-ELISA +; mif | unclear | – | Leschnik et al. (2008) [34] |

| 9 | 2002 | m (n) | 3 | Boston Terrier | travel screening | Ag-ELISA + | United States of America (Florida) | – | Leschnik et al. (2008) [34] |

| 10 | 2009 | f (n) | 6 | Labrador Retriever | travel screening | Ag-ELISA +; mif | Greece | + | a |

| 11 | 2009 | m (n) | 3.5 | crossbreed | travel screening | Ag-ELISA +; mif + | Greece | + | a |

| 12 | 2010 | m | 6 | Rottweiler | incidental finding, hematology | Ag-ELISA +; mif + in blood and urine | Romania | – | a |

| 13 | 2011 | f (n) | 5 | Greyhound | travel screening | Ag-ELISA +; mif + | Spain | + | a |

| 14 | 2011 | m | 5 | Galgo Español | travel screening | Ag-ELISA +; mif + | Spain | + | a |

| 15 | 2011 | f (n) | 5 | Galgo Español | travel screening | Ag-ELISA +; mif + | Greece | + | a |

| 16 | 2011 | f (n) | 1 | Terrier | travel screening | Ag-ELISA +; mif | Serbia | + | a |

| 17 | 2012 | m | 5 | crossbreed | travel screening | Ag-ELISA +; PCR +; mif + | Croatia, southern France | + | a |

| 18 | 2014 | m (n) | 4 | crossbreed | apathy | Ag-ELISA +; PCR–; mif | Hungary | + | a |

| Dirofilaria repens and D. immits | |||||||||

| 1 | before 2001 | f (n) | 4 | crossbreed | subcutaneous nodule | Ag-ELISA: +; Knott test: +; mif +; Maf D. repens | Greece | + | Kleiter et al. (2001) [35] |

| 2 | 2014 | m (n) | 5 | Magyar Vizsla | travel screening | Ag-ELISA +; PCR +; mif + | Hungary (East) | – | a |

| 3 | 2014 | m (n) | 6 | German Shepherd | travel screening | Ag-ELISA +; PCR +;mif + | Hungary (West) | + | a |

| Epidemiological surveys | |||||||||

| 1 | 1999–2003 | Five of 87 dogsFour cases D. immitis, one case D. repens | travel screening | Knott test, Ag-ELISA | Mediterranean | Prosl et al. (2003) [39] | |||

| 2 | 2008 | One of eight D. repens | epidemiological survey | Knott test, PCR | Austria (Lower Austria, Gänserndorf Distict) | Duscher et al. (2009) [20] | |||

| 3 | 2008 | Six of 90 D. repens | epidemiological survey | Knott test, PCR | Austria (Burgenland, Neusiedl District) | a | |||

| Filaroid infection without species determination | |||||||||

| 1 | before 2001 | m | 1 | Kuvasz | travel screening | mif + | Hungary | – | Leschnik et al. (2008) [34] |

| 2 | 2001 | f (n) | 8 | crossbreed | travel screening | mif + | Greece | + | Leschnik et al. (2008) [34] |

| 3 | 2001 | m (n) | 2 | crossbreed | travel screening | mif + | Greece | + | Leschnik et al. (2008) [34] |

| 4 | 2005 | m | 7 | Pudelpointer | incidental finding, histology stomach | mif + | Slovenia | – | a |

aUnpublished patient data archived at the University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna.

bDuscher and Feiler, unpublished data.

Fig 2. Potential autochthonous cases of D. repens in humans, dogs, and mosquitoes in eastern Austria.

D. immitis

Filarioid helminths of the species D. immitis were documented in 25 dogs in Austria (Table 3). Of 16 dogs presenting monoinfections with D. immitis with known sex, eight were male and eight female. Clinical signs of imported dogs were in general occult or mild and resolved after adequate therapy. All cases of D. immitis in Austria were diagnosed during necropsy, travel screening, or routine veterinary examination with hematology, and 81% of the examined dogs had a history of travel activity to the Mediterranean region (e.g., Italy, Greece) prior to infection; no case was suspected to be an autochthonous infection from Austria.

Mixed infections and infections of unspecified filarioid helminths

Mixed D. repens and D. immitis infections were examined in three dogs, all of which had reported travel activity. Microfilariae were observed in the blood of four dogs, without further differentiation of the parasites to species level.

Wildlife Hosts

Blood samples of foxes from eastern (District of Gänserndorf in Lower Austria; n = 36; unpublished data) and western Austria (Tyrol and Vorarlberg; n > 500; unpublished data) were screened for the presence of filarioid helminths. However, to date, neither D. repens nor D. immitis have been observed in Austrian foxes or other possible wild hosts.

Mosquitoes

Various species of the genera Aedes, Ochlerotatus, Culex, Culiseta, Coquillettidia, and Anopheles are potential vectors of Dirofilaria spp. [3,7] in Europe. Several epidemiological studies have been conducted in Austria and neighboring countries; however, in most of these studies, DNA of the pathogens was examined in field-sampled mosquitoes that were classified to species level, and entire animals from the same sampling site and date were pooled. So, the vector competence of several mosquito species remains unclear because this cannot be confirmed if entire mosquitoes (including the abdomen) are used for molecular analysis.

Currently, 46 mosquito species are known to be present in Austria [17]. Of these, Aedes vexans, Ae. albopictus (no stable populations in Austria in 2014), Culiseta annulata, Culex pipiens complex, Anopheles maculipennis complex, An. algeriensis, and Ochlerotatus caspius are potential vectors for D. repens [3,12,17,21–23]. Potential vectors of D. immitis in Austria are Coquillettidia richardii, Ae. albopictus, Oc. caspius, Ae. vexans, An. maculipennis complex, Cx. pipiens complex, and Cx. modestus [3,7,14,17].

D. repens in Austria was detected in mosquitoes in 2012 for the first time in a nationwide mosquito surveillance and monitoring program [22]. DNA of D. repens was examined in pools of An. algeriensis in Rust and An. maculipennis complex in Mörbisch, both in the federal state of Burgenland, bordering Hungary (Fig 2). To date, these are the only findings of autochthonous Dirofilaria spp. in mosquitoes in Austria.

Conclusions

According to Simon et al. (2012), the transmission of D. repens and D. immitis is limited to two main preconditions:

(i) the presence of one mosquito species capable of transmitting the parasites, and (ii) the presence of a minimum number of dogs infected with adult helminths that produce microfilariae.

In Austria, competent mosquito vectors for the transmission of both D. repens and D. immitis are part of the Austrian Culicidae species inventory. The two most common mosquito species in Austria, Ae. vexans and the Cx. pipiens complex, may readily act as potential vectors of these pathogens [21].

The number of infected dogs might be the limiting factor for the establishment of Dirofilaria in Austria. It is estimated that 581,000–600,000 dogs live in 511,000 households in Austria, with a human population of 8,579,747 (Statistik Austria: www.statistik.at, date: 01.01.2015). Most of these dogs are kept in the house; outdoor and/or kennel keeping is uncommon in this country. This circumstance might delay the introduction and establishment of the nematodes and might be the reason why they are to date not autochthonous in Austria, while this is the case for neighboring countries.

The above-mentioned preconditions are themselves influenced by several factors like human behavior with respect to pets (pet travel and health care) and wildlife (e.g., high fox populations after rabies eradication programs), globalization, and climatic factors [7]. Several models have shown that the expansion from southern to central and northern Europe (up to 50° N in the case of D. immitis) is most probable. Both the heartworm predictive model (based on growing degree days) and the Dirofilaria development units show parts of eastern Austria (the regions where most D. repens cases in dogs, the findings in mosquitoes, and the human case were documented) as suitable for the introduction and/or establishment of D. repens as well as D. immitis [24]. More detailed studies should reveal the exact area of predicted establishment, especially for the most westerly spread.

The (potential) autochthonous findings of D. repens in one human, seven dogs, and two mosquito species indicate that this parasite is becoming endemic and establishing itself in Austria. However, a stable establishment of D. repens is still to be seen, as all these cases were documented within a relatively short time span. D. immitis does not appear to be endemic in Austria, but with regard to observations in the neighboring countries (particularly Hungary and Slovakia) it will probably become established in the near future. Therefore, regular monitoring of the mosquito population as well as the wild carnivore population is of urgent need.

The first findings of D. repens in mosquito vectors indicate that D. repens presumably invaded into eastern Austria in recent times. Veterinarians and medical physicians should be aware of possible autochthonous cases with these neglected pathogens in Austria. However, further monitoring of mosquitoes is necessary to observe the expansion of the distribution of D. repens and the possible invasion by D. immitis in Austria.

Key Learning Points

Autochthonous findings of D. repens in mosquitoes, as well as potential autochthonous cases in dogs and humans, suggest that this parasite is establishing itself in Austria.

Until now, D. immitis is only associated with travel activity, and the parasite is not (yet) endemic in Austria.

The increase of cases with both D. repens and D. immitis in dogs in recent years makes it clear that veterinarians should also consider these parasites in the diagnosis of Austrian dogs without prior travel activity.

Mosquito surveillance and observation of canid wildlife hosts for the presence of D. repens and D. immitis is necessary to evaluate the possible establishment of both parasites in the future.

Top Five Papers

Genchi C, Kramer LH, Rivasi F (2011) Dirofilarial infections in Europe. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 11:1307–17. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2010.0247.

Morchón R, Carretón E, González-Miguel J, Mellado-Hernández I (2012) Heartworm Disease (Dirofilaria immitis) and Their Vectors in Europe—New Distribution Trends. Front Physiol 3:196. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00196.

Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F, Brianti E, Traversa D, Petrić D, et al. (2013) Vector-borne helminths of dogs and humans in Europe. Parasit Vectors 6:16. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-16.

Silbermayr K, Eigner B, Joachim A, Duscher GG, Seidel B, et al. (2014) Autochthonous Dirofilaria repens in Austria. Parasit Vectors 7:226. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-226.

Simón F, Siles-Lucas M, Morchón R, González-Miguel J, Mellado I, et al. (2012) Human and animal dirofilariasis: the emergence of a zoonotic mosaic. Clin Microbiol Rev 25:507–44. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00012-12.

Funding Statement

The work of Hans-Peter Fuehrer was funded by the ERA-Net BiodivERsA, with the national funders FWF I-1437, ANR-13-EBID-0007-01, and DFG BiodivERsA KL 2087/6-1 as part of the 2012-13 BiodivERsA call for research proposals. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F, Brianti E, Traversa D, Petrić D, Genchi C, et al. Vector-borne helminths of dogs and humans in Europe. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6: 16 10.1186/1756-3305-6-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Otranto D, Cantacessi C, Dantas-Torres F, Brianti E, Pfeffer M, Genchi C, et al. The role of wild canids and felids in spreading parasites to dogs and cats in Europe. Part II: Helminths and arthropods. Vet Parasitol. 2015;213: 24–37. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simón F, Siles-Lucas M, Morchón R, González-Miguel J, Mellado I, Carretón E, et al. Human and animal dirofilariasis: the emergence of a zoonotic mosaic. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25: 507–44. 10.1128/CMR.00012-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tasić-Otašević SA, Trenkić Božinović MS, Gabrielli S V, Genchi C. Canine and human Dirofilaria infections in the Balkan Peninsula. Vet Parasitol. 2015;209: 151–6. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sałamatin R V, Pavlikovska TM, Sagach OS, Nikolayenko SM, Kornyushin V V, Kharchenko VO, et al. Human dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria repens in Ukraine, an emergent zoonosis: epidemiological report of 1465 cases. Acta Parasitol. 2013;58: 592–8. 10.2478/s11686-013-0187-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otranto D, Eberhard ML. Zoonotic helminths affecting the human eye. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4: 41 10.1186/1756-3305-4-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morchón R, Carretón E, González-Miguel J, Mellado-Hernández I. Heartworm Disease (Dirofilaria immitis) and Their Vectors in Europe—New Distribution Trends. Front Physiol. 2012;3: 196 10.3389/fphys.2012.00196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albanese F, Abramo F, Braglia C, Caporali C, Venco L, Vercelli A, et al. Nodular lesions due to infestation by Dirofilaria repens in dogs from Italy. Vet Dermatol. 2013;24: 255–e56. 10.1111/vde.12009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deplazes P, Guscetti F, Wunderlin E, Bucklar H, Skaggs J, Wolff K. Endoparasitenbefall bei Findel- und Verzicht-Hunden in der Südschweiz. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 1995;137: 172–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bucklar H, Scheu U, Mossi R, Deplazes P. Breitet sich in der Südschweiz die Dirofilariose beim Hund aus? Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 1998;140: 255–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Genchi C, Kramer LH, Rivasi F. Dirofilarial infections in Europe. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11: 1307–17. 10.1089/vbz.2010.0247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bocková E, Rudolf I, Kočišová A, Betášová L, Venclíková K, Mendel J, et al. Dirofilaria repens microfilariae in Aedes vexans mosquitoes in Slovakia. Parasitol Res. 2013;112: 3465–70. 10.1007/s00436-013-3526-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sassnau R, Dyachenko V, Pantchev N, Stöckel F, Dittmar K, Daugschies A. Dirofilaria repens infestation in a sled dog kennel in the federal state of Brandenburg (Germany). Diagnosis and therapy of canine cutaneous dirofilariosis. Tierarztl Prax Ausgabe K Kleintiere—Heimtiere. 2009;37: 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kronefeld M, Kampen H, Sassnau R, Werner D. Molecular detection of Dirofilaria immitis, Dirofilaria repens and Setaria tundra in mosquitoes from Germany. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7: 30 10.1186/1756-3305-7-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Czajka C, Becker N, Jöst H, Poppert S, Schmidt-Chanasit J, Krüger A, et al. Stable transmission of Dirofilaria repens nematodes, northern Germany. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20: 328–31. 10.3201/eid2002.131003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Svobodová Z, Svobodová V, Genchi C, Forejtek P. The first report of authochthonous dirofilariosis in dogs in the Czech Republic. Helminthologia. 2006;43: 242–245. 10.2478/s11687-006-0046-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zittra C, Kocziha Z, Pinnyei S, Harl J, Kieser K, Laciny A, et al. Screening blood-fed mosquitoes for the diagnosis of filarioid helminths and avian malaria. Parasit Vectors. BioMed Central Ltd.; 2015;8: 16 10.1186/s13071-015-0637-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Auer H, Susani M. Der erst authochthone Fall einer subkutanen Dirofilariose in Österreich. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2008;120: 104–6. 10.1007/s00508-008-1031-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Auer H. Die Dirofilariose des Menschen Epidemiologie and Nosologie einer gar nicht so seltenen Parasitose in Osterreich (Nematoda, Spirurida, Onchocercidae). Denisia; 2004; 463–471.

- 20.Duscher G, Feiler A, Wille-Piazzai W, Bakonyi T, Leschnik M, Miterpáková M, et al. Nachweis von Dirofilarien in österreichischen Hunden. Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr. 2009;122: 199–203. 10.2376/0005-9366-122-199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudolf I, Šebesta O, Mendel J, Betášová L, Bocková E, Jedličková P, et al. Zoonotic Dirofilaria repens (Nematoda: Filarioidea) in Aedes vexans mosquitoes, Czech Republic. Parasitol Res. Springer Verlag; 2014;113: 4663–7. 10.1007/s00436-014-4191-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silbermayr K, Eigner B, Joachim A, Duscher GG, Seidel B, Allerberger F, et al. Autochthonous Dirofilaria repens in Austria. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7: 226 10.1186/1756-3305-7-226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becker N, Petric D, Zgomba M, Boase C, Madon M, Dahl C, et al. Mosquitoes and Their Control: Second Edition. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin; Heidelberg; 2010. 10.1007/978-3-540-92874-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Genchi C, Rinaldi L, Cascone C, Mortarino M, Cringoli G. Is heartworm disease really spreading in Europe? Vet Parasitol. 2005;133: 137–48. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bardach H, Heimbucher J, Raff M. Subkutane Dirofilaria (Nochtiella) repens-Infektion beim Menschen—Erste Fallbeschreibung in Österreich und Übersicht der Literatur. Wien Klin Wochenschr. Universitats-Hautklinik, Alser Strasse 4, A-1090 Vienna, Austria.; 1981;93: 123–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lammerhuber C, Auer H, Bartl G, Dressler H. Subkutane Dirofilaria (Nochtiella) repens-Infektion im Oberlidbereich. Spektrum der Augenheilkd. 1990;4: 162–164. 10.1007/BF03163592 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schuller-Petrovic S, Kern TH, Haßl A, Hermentin K, Gebhart W. Subkutane Dirofilariose beim Menschen—Ein Fallbericht aus Österreich. H+G Zeitschrift fur Hautkrankheiten. 1996;71: 927–931. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bischof G, Simader H, Stemberger H, Sattmann H. Überraschende Diagnose einer fraglichen Beinvenenthrombose durch ultarschallgezielte Feinnadelpunktion (Kasuistik). Helminthological Colloquium. 2003 Nov 13. Vienna, Austria. Abstract.

- 29.Auer H, Weinkammer H, Bsteh A, Schnayder C, Dieze O, Kunit G, et al. Ein seltener Fall einer Dirofilaria repens-Infestation des Nebenhodens. Mitt Osterr Ges Tropenmed Parasitol. 1997;19: 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun H, Koele W, Stammberger H, Ranner G, Gröll R. Endoscopic removal of an intraorbital “Tumor”: A vital surprise. Am J Rhinol. 1999;13: 469–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groell R, Ranner G, Uggowitzer MM, Braun H. Orbital dirofilariasis: MR findings. Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20: 285–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Böckle BC, Auer H, Mikuz G, Sepp NT. Danger lurks in the Mediterranean. Lancet (London, England). 2010;376: 2040 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61258-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ritter A, Egger S, Emesz M. Dirofilariose: Subkonjunktivale Infektion mit Dirofilaria repens. Ophthalmologe. 2012;109: 788–90. 10.1007/s00347-012-2541-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leschnik M, Löwenstein M, Edelhofer R, Kirtz G. Imported non-endemic, arthropod-borne and parasitic infectious diseases in Austrian dogs. WienKlinWochenschr.; 2008;120: 59–62. 10.1007/s00508-008-1077-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kleiter M, Luckschander N, Willmann M. Kutane Dirofilariose (Dirofilaria repens) bei zwei nach Österreich importierten Hunden. Kleintierpraxis. 2001;46: 283–288. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pantchev N, Etzold M, Daugschies A, Dyachenko V. Diagnosis of imported canine filarial infections in Germany 2008–2010. Parasitol Res. 2011;109 Suppl: S61–76. 10.1007/s00436-011-2403-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hinaidy HK, Bacowsky H, Hinterdorfer F. Einschleppung der Hunde-Filarien Dirofilaria immitis und Dipetalonema reconditum nach Osterreich. Zentralbl Veterinarmed B. 1987;34: 326–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Löwenstein M, Meissel H, Koller J. Dirofilaria immitis infection of dogs in Austria. Wien Tierarztl Monatsschr; 1988;75: 420–424. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prosl H, Schwendenwein I, Kolm U. Dirofilariosis in Austria. Helminthological Colloquium. 2003 Nov 13. Vienna, Austria. Abstract.