Abstract

N-Phenyl-N-(piperidin-2-ylmethyl)propionamide based bivalent ligands are unexplored for the design of opioid based ligands. Two series of hybrid molecules bearing N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-2-ylmethyl)propionamide derived small molecules conjugated with an enkephalin analogues with and without a linker (β-alanine) were designed and synthesized. Both bivalent ligand series exhibited remarkable binding affinities from nanomolar to subnanomolar range at both μ and δ opioid receptors and displayed potent agonist activities as well. The replacement of Tyr with Dmt and introduction of a linker between the small molecule and enkephalin analogue resulted in highly potent ligands. Both series of ligands showed excellent binding affinities at both μ (0.6–0.9 nM) and δ (0.2–1.2 nM) opioid receptors respectively. Similarly, these bivalent ligands exhibited potent agonist activities in both MVD and GPI assays. Ligand 17 was evaluated for in vivo antinociceptive activity in non-injured rats following spinal administration. Ligand 17 was not significantly effective in alleviating acute pain. The most likely explanations for this low intrinsic efficacy in vivo despite high in vitro binding affinity, moderate in vitro activity are (i) low potency suggesting that higher doses are needed; (ii) differences in experimental design (i.e. non-neuronal, high receptor density for in vitro preparations versus CNS site of action in vitro); (iii) pharmacodynamics (i.e. engaging signalling pathways); (iv) pharmacokinetics (i.e. metabolic stability). In summary, our data suggest that further optimisation of this compound 17 is required to enhance intrinsic antinociceptive efficacy.

Keywords: Opioids, Pain, Opioid receptors, Enkephalin

The opioid receptors belong to the superfamily of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and play important roles in pain perception and regulation. They are classified into three different subtype’s μ, δ and κ opioid receptors. Opioids have been used for the treatment of moderate to severe pain and for their psychotropic effects since ancient times. Indeed, exogenous agonists of opioid receptors elicit marked analgesic effects, along with serious side effects such as respiratory depression, sedation, constipation, nausea, tolerance and dependence. Most of the present opioid analgesics exert their analgesic and adverse effects primarily through the μ opioid receptors. For the past two decades there has been considerable interest in the synthesis of nonselective μ/δ ligands with different combinations of agonist and (or) antagonist activities at each of the opioid receptors, which have been shown to exhibit valuable analgesic properties.1–8 The new promising approach in the opioid drug development is ligand designed with mixed μ agonist/δ agonist profile or μ agonist/δ antagonist profile.9–11 Several reports indicate that the dimerization or oligomerization of GPCRs,12 and the existence of dimers for opioid receptors particularly between μ and δ opioid receptors have been reported.13 Recent pharmacological studies have demonstrated that the development of tolerance to μ-opioids can be suppressed by co-administration of δ opioid receptor agonists or antagonists, and that δ agonists can increase the potency and efficacy of μ agonists.14–17 It appears that this is based on the beneficial modulatory interactions existing between μ and δ opioid receptors.

The endogenous neuropeptides enkephalins, β-endorphins, endomorphins and dynorphins which interact with the δ, μ and κ opioid receptors respectively.18 These endogenous peptides acts as both neuromodulators and hormones, and are responsible for a broad spectrum of physiological effects. The subsequent elongation or truncation modifications of these endogenous peptides led to highly promising opioid agonists.6,19 Many interesting and useful selective peptide ligands for the opioid receptors have been developed and used extensively. The peptide fragments for our bivalent ligands (Tyr-DAla-Gly-Phe and Dmt-DAla-Gly-Phe) are potent well established opioid ligands. Portoghese et al.20 reported a conjugation of Tyr-(Gly)n peptide analogues to the N-phenyl-N-piperidin-4-yl)propionamide moiety and the resulting conjugate compounds showed very weak or no opioid activity. During the last decade our group has shown promising progress in synthesis of bivalent μ/δ ligands based on enkephalin analogues conjugated to the different positions of the 4-anilidopiperidine core and fentanyl molecule. 4,21–23 Our group reported a Dmt-substituted enkephalin-like tetrapeptide with a N-phenyl-N-piperidin-4-yl)propionamide moiety. These ligands exhibited good biological activities in vitro and demonstrated potent in vivo antihyperalgesic and antiallodynic effects in the tail-flick assay.4 Based on these results recently we reported a series of hybrid molecules containing the C-terminal of enkephalin analogues attached to the amino group of 4-anilidopiperidine core small molecules which were synthesized and pharmacologically evaluated.24 All these bivalent ligands showed good binding affinity as well as potent agonist activities in MVD and GPI assays at both μ and δ opioid receptors. The scientists at Neurosearch25 and Sepracor Inc.26 explored the N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-4-ylmethyl) propionamide, N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-3-ylmethyl)propionamide derivatives with substituted phenethyl groups as potent opioid agonists. They substituted a variety of heterocyclic compounds in place of the phenyl group on the ‘N’ piperidine. The above literature precedence and earlier promising results on opioid bivalent ligands from our group inspired us to explore the bivalent ligands based on the conjugation of enkephalin analogues to 5-amino substituted tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl) methyl moiety with N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-2-ylmethyl)propionamide based small molecules. Similarly, the second series of molecules explored by enkephalin analogues directly conjugated to the N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-2-ylmethyl)propionamide moiety. The small molecules 1 and 2 are structurally relevant to the 4-anilidopiperidine small molecules, the advantages of these molecules having additional hydrophobic cyclohexyl group and amine substitution on 5th position of tetrahydronaphthalen-2yl-methyl moiety. We expected the lipophilic nature of the molecules 1 and 2 will increase cell permeability of attached peptides, and consequently their bioavailability.27 Another interesting feature of these molecules amino group on tetrahydronaphthalen-2yl-methyl moiety was easily accessible to attach to the C-terminus enkephalin analogues with and without a linker. N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-2-ylmethyl) propionamide 11 analogues remain unexplored in the literature as potential opioid ligands for their structure activity relationship and represent a promising new approach in the design of hybrid nonpeptide-peptide analgesics. The rationale behind the design of second series of bivalent ligands (16–18), Lee et al.4 reported a Dmt-substituted enkephalin-like tetrapeptide with a N-phenyl-N-piperidin-4-yl)propionamide moiety. The resulted ligands exhibited good biological activities in vitro and demonstrated potent in vivo antihyperalgesic and antiallodynic effects. In our designs we replaced the N-phenyl-N-piperidin-4-yl)propionamide moiety with N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-2-ylmethyl)propionamide (11) and attached the enkephalin peptide analogues in similar fashion. The structural difference between N-phenyl-N-piperidin-4-yl)propionamide moiety and N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-2-ylmethyl)propionamide (11) is connectivity of piperidine ring to N-phenylpropionamide group, one is at 4th position and the other one is 2nd position. Our interest here is to study the effect of piperdine ring connectivity to N-phenylpropionamide group on opioid receptors (μ and δ) binding affinity and activity. The present study constitutes ongoing developments in our laboratory towards the design and synthesis of novel bivalent ligands based on enkephalin analogues and 4-anilidopiperidine small molecules.

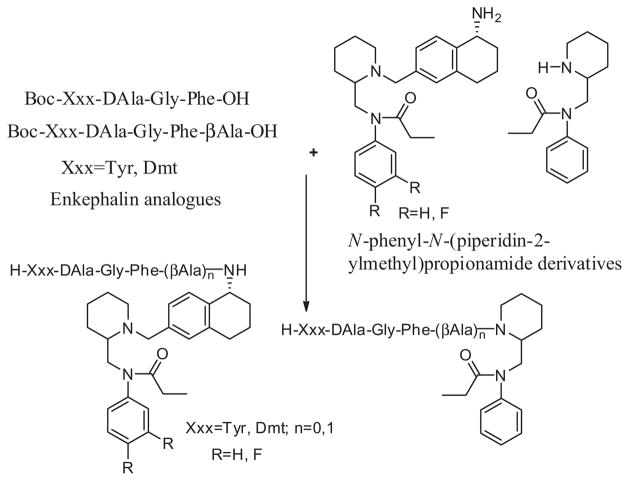

We take the N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-2-ylmethyl)propionamide 11 as the core template, which can be expanded towards designing novel ligands. The first series of bivalent ligands were designed based on the small molecule 1 (N-((1-(((R)-5-amino-5,6,7,8-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl)methyl)piperidin-2-yl)methyl)-N-phenylpropionamide) and fluoro analogue 2 conjugated to the C-terminal of the enkephalin peptide derivatives with and without a linker (Fig. 1). The rationale for choosing fluoro analogue 2 into bivalent ligands, the fluorine imparts a variety of properties to the molecules, including enhanced binding interactions, metabolic stability, changes in physical properties, and selective reactivities. 28 The Dmt-substituted enkephalin-like tetrapeptide with a N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-4-yl)propionamide moiety gave a promising results (in vitro and in vivo) at the μ and δ opioid receptors,4 and similar approach we followed here in the design of second series ligands. The C-terminal enkephalin peptide derivatives conjugated to the N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-2-ylmethyl)propionamide 11 with and without a linker (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Design principle of bivalent ligands.

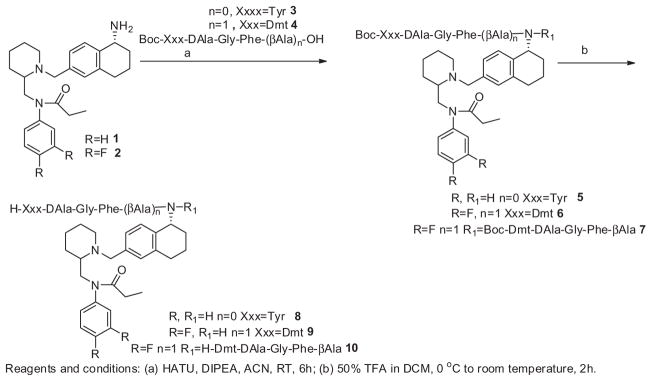

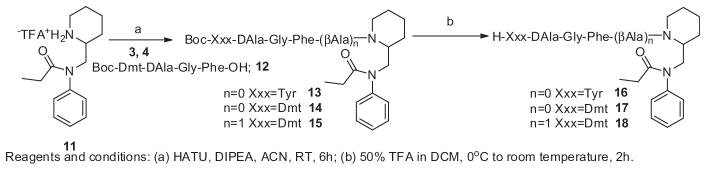

The synthetic procedures for small molecules 1 and 2, and their structure activity relationship studies are going to communicate as a different account. The enkephalin analogues 3 (Boc-Tyr-DAla-Gly-Phe-OH), 4 (Boc-Dmt-DAla-Gly-Phe-βAla-OH) and 12 (Boc-Dmt-DAla-Gly-Phe-OH) were prepared by solution phase peptide synthesis following the Nα-Boc strategy by previously reported.21 The hybrid molecules 8–10 were prepared starting from the small molecules 1 and 2 according to Scheme 1. The enkephalin peptides 3 and 4 are conjugated to the small molecules 1 and 2 in presence of HATU/DIPEA in acetonitrile to afford the Boc-protected bivalent ligands 5, 6 and 7. Surprisingly, during the coupling of enkephalin peptide 4 to the small molecule 2, we obtained two products wherein the major product 6 has a single peptide unit attached to the small molecule, and the other minor product 7 has two peptide units conjugated to the small molecule. Without further purification the Boc-protected analogues 5 (mixture of 6 and 7) were treated with 50% trifluoroacetic acid in dichloromethane to yield the crude final bivalent ligands 8, 9 and 10. The second series of bivalent ligands were prepared according to Scheme 2. The enkephalin peptides 3, 4 and 12 were conjugated to the N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-2-ylmethyl)propionamide moiety 11 in the presence of HATU/DIPEA in acetonitrile to afford the Boc-protected analogues 13, 14 and 15 which were followed by removal of the Boc group with 50% trifluoroacetic acid in dichloromethane thus obtaining the crude bivalent ligands 16, 17 and 18. The Boc-protected analogues 5–7 and 13–15 were triturated with ether, filtered and washed with excess ether, and without further purification the Boc group was deprotected to obtain the final bivalent ligands. The final crude ligands were purified by RP-HPLC to give pure ligands as white powders in overall yields of 35–40%. The purity of the final ligands was determined as >95% by analytical HPLC. The final bivalent ligands were characterised and their purity confirmed by analytical HPLC, 1H NMR, HRMS. For all the data, see Supporting information.

Scheme 1.

Preparation of enkephalin analogues with 5-amino substituted tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl)methyl bivalent ligands.

Scheme 2.

Preparation of enkephalin analogues with N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-2-ylmethyl)propionamide bivalent ligands.

The opioid receptor binding affinities of the synthesized bivalent ligands were evaluated using human δ opioid receptors (hDOR) and rat μ-opioid receptors (rMOR) with cells that stably express these receptors as previously described.29 [3H]DPDPE and [3H]DAMGO were used as competitive radio ligands, respectively. The tissue bioassays (mouse vas deferens: MVD, guinea pig isolated ileum: GPI) also were performed to characterise the agonist function at δ and μ opioid receptors as described previously.30 The affinities of the two series of bivalent ligands were evaluated at the μ and δ opioid receptor. In addition, the functional activity of these hybrid molecules was also investigated through MVD and GPI assay (Tables 2 and 3). The two series of new opioid bivalent ligands showed very promising binding affinities and functional bioactivities at the δ and μ opioid receptors.

Table 2.

Functional assay result for bivalent ligands at MOR and DOR

| Compd | a MVD (δ) | a GPI (μ) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| IC50 (nM) | ||

| 1 | 18% 1 μM | 1005 ± 58 |

| 2 | 22% 1 μM | 10% 1 μM |

| 8 | 540 ± 230 | 95 ± 16 |

| 9 | 57 ± 9.4 | 5.7 ± 2.5 |

| 10 | 6.1 ± 1.5 | 2.1 ± 0.45 |

Concentration at 50% inhibition of muscle contraction at electrically stimulated isolated tissues.

Table 3.

Receptor affinity and functional bioactivity of bivalent ligands

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R3 | Binding Ki (nM)

|

Ki μ/δ | c MVD δ | c GPI μ | |||

| b log IC50 | a MOR (μ) | b log IC50 | a DOR (δ) | |||||

| 16 | Tyr-DAla-Gly-Phe– | −8.49 ± 0.06 | 2 | −8.31 ± 0.08 | 2 | 1 | 7.1 ± 1.5 | 21 ± 7.1 |

| 17 | Dmt-DAla-Gly-Phe– | −8.76 ± 0.30 | 0.8 | −9.28 ± 0.03 | 0.2 | 4/1 | 0.47 ± 0.06 | 0.73 ± 0.06 |

| 18 | Dmt-DAla-Gly-Phe-βAla | −9.56 ± 0.30 | 0.9 | −8.92 ± 0.04 | 1.2 | 1 | 0.45 ± 0.26 | 4.1 ± 2.1 |

Competition analyses against radiolabeled ligand ([3H]DPDPE for DOR δ [3H]DAMGO for μ were carried out using rat brain membranes.

Logarithmic values determined from the nonlinear regression analysis of data collected from at least two independent experiments.

Concentration at 50% inhibition of muscle contraction at electrically stimulated isolated tissues.

The small molecules 1 and 2 are showed very good binding affinity (69 nM and 33 nM) at μ opioid receptors respectively, with high selectivity towards the μ opioid receptor. When the C-terminus of the enkephalin analogue was attached to the amino group of the small molecule 1 the resultant bivalent ligand 8 exhibited 1 nM a 33 fold increase in binding affinity for the μ receptor, and a 56 fold increases for a δ receptor biding affinity of 160 nM comparative to the small molecule 1. The introduction of a linker (β-alanine) in between the enkephalin analogues and the small molecules, and the replacement of Tyr1 with Dmt1 attached to the fluoro analogue of small molecule 2 the bivalent ligand 9 which exhibited μ receptor binding affinity retained (0.7 nM) and almost 400 fold increase in the δ receptor binding affinity to 0.4 nM compared to 8. The bivalent ligand 10 contains two enkephalin peptide units with small molecule exhibited almost similar binding affinities (0.6 nM) at both receptors as does ligand 9 which contains one enkephalin unit. In second series of bivalent ligands 16, 17 and 18 enkephalin analogues directly attached to the N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-2-ylmethyl)propionamide moiety with and without a linker. The second series of bivalent ligands 16, 17 and 18 showed excellent binding affinities towards μ and δ opioid receptors (Table 3). The enkephalin peptide 3 directly attached to the small molecule 11 resulting in the bivalent ligand 16 showed good and balanced binding affinities (2 nM) at μ and δ opioid receptors. Ligand 17 retained similar binding affinities like ligand 16 with 0.8 nM affinity at the μ opioid receptor, with a 10 fold increased binding affinity of 0.2 nM at the δ opioid receptor. In ligand 18 the introduction of a linker between enkephalin analogue and small molecule showed almost the same binding affinities as ligand 17. Thus replacement of Tyr with Dmt and introducing a β-alanine as the linker in this series of ligands not significant influence the binding affinities towards the receptors as were observed profoundly in the earlier series.

All analogues showed good opioid agonist activities in the GPI and MVD assays and were observed to correlate to their in vitro binding affinities at μ and δ opioid receptors respectively (Tables 1–3). Among these novel bivalent ligands 17 and 18 are found to have very potent agonist activities at both in MVD (0.47 and 0.45 nM) and GPI (0.73 and 4.1 nM) assays respectively. The bivalent ligands 17 and 18 showed very balanced activities at μ and δ opioid receptors. The lead compound 17 was evaluated in vivo (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Binding affinities of bivalent ligands at μ/δ opioid receptors

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R | R1 | R2 | Binding Ki (nM)

|

Ki μ/δ | |||

| b log IC50 | a MOR (μ) | b log IC50 | a DOR (δ) | |||||

| 1 | H | H | H | −6.83 ± 0.09 | 69 | −4.92 ± 0.09 | 5200 | 1/79 |

| 2 | F | H | H | −7.25 ± 0.09 | 33 | −4.72 ± 0.70 | 9000 | 1/270 |

| 8 | H | Tyr-DAla-Gly-Phe– | H | −8.69 ± 0.17 | 1 | −6.47 ± 0.08 | 160 | 1/160 |

| 9 | F | Dmt-DAla-Gly-Phe-βAla– | H | −9.10 ± 0.23 | 0.7 | −8.79 ± 0.06 | 0.4 | 1.75/1 |

| 10 | F | Dmt-DAla-Gly-Phe-βAla– | Dmt-DAla-Gly-Phe-βAla– | −8.89 ± 0.21 | 0.6 | −8.85 ± 0.04 | 0.6 | 1 |

Competition analyses against radiolabeled ligand ([3H]DPDPE for DOR δ [3H]DAMGO for μ were carried out using rat brain membranes.

Logarithmic values determined from the nonlinear regression analysis of data collected from at least two independent experiments.

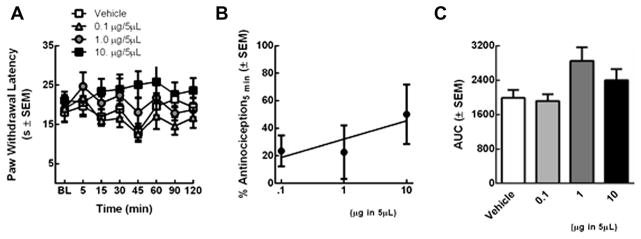

Figure 2.

(A) Ligand 17 was evaluated in SD rats using a radiant heat assay (B) Ligand 17 antinociceptive dose-response curve (C) Ligand 17 dose-dependency was assessed by constructing a dose response curve.

Three doses of Ligand 17 or vehicle (0.1, 1.0, and 10 μg in 5 μl; n = 5/treatment) were evaluated in non-injured rats using a radiant heat assay. At no time were paw withdrawal latencies (PWLs) of rats treated with Ligand 17 significantly longer than those vehicle-treated rats and baseline values (p >0.05; Fig. 2a). The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to determine if the duration of effect depended on dose; no significantly differences in the AUC were observed (Fig. 2c). The % antinociception was calculated and reached a maximal level of 63 ± 19 % (10 μg/5μL) 5 minutes after intrathecal administration; this was not significantly higher than vehicle treatment (p = 0.65; Fig. 2b). Ligand 17 did not significantly alleviate acute thermal pain in non-injured rats despite high affinity and in vitro functional activity at μ and δ opioid receptors. Detailed in vivo experimental procedures are given in the notes section.

The enkephalin analogues conjugated with N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-2-ylmethyl)propionamide derivatives represent an new family of μ and δ hybrid ligands and exhibit very good and balanced binding affinities with good agonist properties at μ and δ opioid receptors. From the structure activity relationship studies the small molecule 2 exhibited excellent binding affinities and selectivity towards the μ opioid receptor. The conjugation of enkephalin analogues to the small molecules, and the resultant bivalent ligands exhibited good binding affinities and agonistic activities as well. The introduction of a linker between the small molecule and peptide, and the replacement of Tyr with Dmt afforded highly potent ligands at both receptors. In the second series of bivalent ligands (16–18) introduction of a linker in between small molecule and peptide does not have a much effect on the bioactivity. Ligand 17 was evaluated for in vivo antinociceptive activity in non-injured rats following spinal administration. This local administration at the site of the first synapse was chosen to optimise delivery to the site of action and thus evaluate maximal intrinsic efficacy. At the doses tested, Ligand 17 was not significantly effective in alleviating acute pain. The most likely explanations for this low intrinsic efficacy in vivo despite high in vitro binding affinity, moderate in vitro activity are (i) low potency suggesting that higher doses are needed; (ii) differences in experimental design (i.e. non-neuronal, high receptor density for in vitro preparations versus CNS site of action in vitro); (iii) pharmacodynamics (i.e. engaging signalling pathways); (iv) pharmacokinetics (i.e. metabolic stability). In summary, our data suggest that further optimisation of this compound 17 is required to enhance intrinsic antinociceptive efficacy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by grants from the U.S. Public Health Service NIDA (Grants 314450 NIDA 2P01 DA006284). We thank Christine Kasten for assistance with the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ACN

acetonitrile

- Boc

tert-butyloxycarbonyl

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- DAMGO

[D-Ala2, NMePhe4, Gly5-ol]enkephalin

- DALEA

[D-Ala2, Leu5] enkephalinamide

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DIPEA

N,N-diisopropylethylamine

- HBTU

N,N,N′,N′-tetra methyl-O-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)uronium hexafluorophosphate

- hDOR

human δ opioid receptor

- Dmt

2,6-dimethyltyrosine

- DPDPE

c[D-Pen2, DPen5]enkephalin

- GPI

guinea pig isolated ileum

- HATU

1-[bis(dimethylamino) methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium3-oxid hexafluorophosphate

- HRMS

high resolution mass spectrometry

- rMOR

rat μ opioid receptor

- MVD

mouse vas deferens

- RP-HPLC

reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography

- RT

room temperature

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- TLC

thin layer chromatography

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.10.081.

References and notes

- 1.Mosberg HI, Yeomans L, Harland AA, Bender AM, Sobczyk-Kojiro K, Anand JP, Clark JM, Jutkiewicz EM, Traynor JR. J Med Chem. 2013;56:2139. doi: 10.1021/jm400050y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mosberg HI, Yeomans L, Anand JP, Porter V, Sobczyk-Kojiro K, Traynor JR, Jutkiewicz EM. J Med Chem. 2014:3148. doi: 10.1021/jm5002088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiller PW, Fundytus ME, Merovitz L, Weltrowska G, Nguyen TMD, Lemieux C, Chung NN, Coderre TJ. J Med Chem. 1999;42:3520. doi: 10.1021/jm980724+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee YS, Kulkarani V, Cowell SM, Ma SW, Davis P, Lai J, Porreca F, Vardanyan R, Hruby VJ. J Med Chem. 2011;54:382. doi: 10.1021/jm100982d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Podolsky AT, Sandweiss A, Hua J, Bilsky EJ, Cain JP, Kumirov VK, Lee YS, Hruby VJ, Vardanyan RS, Vanderah TW. Life Sci. 2013;93:1010. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giri AK, Hruby VJ. Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2014;23:22. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2014.856879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiller PW. Life Sci. 2010;86:598. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horan PJ, Mattia A, Bilsky EJ, Weber S, Davis TP, Yamamura HI, Malatynska E, Appleyard SM, Slaninova J, Misicka A, Lipkowski AW, Hruby VJ, Porreca F. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265:1446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ananthan S. AAPS J [electronic resource] 2006;8(1):E118–E1125. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morphy R, Kay C, Rankovic Z. Drug Discovery Today. 2004;15:641. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis MP. Expert Opin Drug Disc. 2010;5:1007. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2010.511473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.George SR, O’Dowd BF, Lee SP. Nat Rev Drug Disc. 2002;1:808. doi: 10.1038/nrd913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomes I, Filipovska J, Jordan BA, Devi LA. Methods. 2002;27:358. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao GM, Wu D, Soong Y, Shimoyama M, Berezowska I, Schiller PW, Szeto HH. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:188. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.1.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang Q, Mosberg HI, Porreca F. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;254:683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porreca F, Takemori AE, Sultana M, Portoghese PS, Bowen WD, Mosberg HI. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;263:147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gendron L, Pintar JE, Chavkin C. Neuroscience. 2007;150:807. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasternak GW, Goodman R, Synder SH. Life Sci. 1975;16:1765. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(75)90270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janecka A, Fichna J, Janecki T. Curr Top Med Chem. 2004;4:1. doi: 10.2174/1568026043451618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Essawi MYH, Portoghese PS. J Med Chem. 1983;26:348. doi: 10.1021/jm00357a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petrov RR, Vardanyan RS, Lee YS, Ma S-W, Davis P, Begay LJ, Lai J, Porreca F, Hruby VJ. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:4946. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.06.040.All solvents, reagents, and starting materials were obtained from commercial sources unless otherwise indicated. The enkephalin peptide analogues 3 and 4 were prepared by solution phase peptide synthesis following the Nα-Boc strategy by utilizing HBTU as the coupling reagent with DIPEA as base and acetonitrile. All reactions were performed under N2 unless otherwise noted. The final ligands 8, 9, 10, 16, 17 and 18 used for the biological assay were purified by RP-HPLC using a semi preparative Vydac (C4-bonded, 300 Å) column and a gradient elution at a flow rate of 3 mL/min. The gradient used was 10–90% acetonitrile in 0.1% aqueous TFA over 40 min. Approximately 10 mg of crude peptide was injected each time, and the fractions containing the purified peptide were collected and lyophilized to dryness. The purity of the final products, determined by NMR analysis, HRMS and by analytical RPHPLC (Vydac 218 TP C18 10 micron length 250 mm) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. 1H NMR spectra were performed in DMSO-d6 solution on Bruker DRX 500 chemical shifts were referred residual proton signal of DMSO at 2.5 ppm in the case of DMSO-d6 solution.In vivo assay: Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (225–300 g; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were kept in a temperature-controlled environment with lights on 07:00–19:00 with food and water available ad libitum. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the policies and recommendations of the International Association for the Study of Pain, the National Institutes of Health, and with approval from the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Arizona for the handling and use of laboratory animals. Surgical methods: Rats were anesthetized (ketamine/xylazine anesthesia, 80/ 12 mg/kg ip; Sigma–Aldrich) and placed in a stereotaxic head holder. The cisterna magna was exposed and incised, and an 8-cm catheter (PE-10; Stoelting) was implanted as previously reported, terminating in the lumbar region of the spinal cord.31 Catheters were sutured (3-0 silk suture) into the deep muscle and externalized at the back of the neck. After a recovery period (≥7 days) after implantation of the indwelling cannula, vehicle (10% DMSO: 90% MPH2O, n = 7) or Ligand 17 (0.1, 1, 10 μg; n = 5/dose) were injected in a 5 μL volume followed by a 9 μl saline flush. Catheter placement was verified at completion of experiments.Behavioral assay: Paw-flick latency32 was determined as follows. Rats were allowed to acclimate to the testing room for 30 minutes prior to testing. Basal paw withdrawal latencies (PWLs) to an infrared radiant heat source were measured (Intensity = 40) and ranged between 16.0 and 20.0 s. A cutoff time of 33.0 seconds was used to prevent tissue damage. After a single, intrathecal injection (i.t.) of ligand 17 or vehicle, PWLs were re-assessed 7 times up to 2 h or until they returned to baseline values. Maximal percent efficacy was calculated and expressed as: % Antinociception = 100*(test latency after drug treatment – baseline latency)/(cutoff – baseline latency).Statistics: All data were analyzed by non-parametric two-way analysis of variance (anova; post hoc: Neuman–Kuels) in FlashCalc (Dr Michael H. Ossipov, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA); areas under the curve were compared by one-way ANOVA. Differences were considered to be significant if P ≤ 0.05. All data were plotted in GraphPad Prism 6.Preparation of compound 5: To an ice-cold stirred solution of the Boc-protected enkephalin peptide 4 (Boc-Tyr-DAla-Gly-Phe-OH) (137 mg, 0.21 mmol, 1 equiv) in dry acetonitrile (6 mL) was added DIPEA (0.16 mL, 0.91 mmol, 4 equiv) and HATU (0.16 g, 0.43 mmol, 2 equiv) followed by N-((1-(((R)-5-amino-5,6,7,8-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl)methyl)piperidin-2-yl)methyl)-N-phenylpropionamide 1 (95 mg, 0.18 mmol, 1 equiv). The resulting reaction mixture was stirred for 4–6 h at room temperature. The solvent was stripped of under reduced pressure, and the resultant residue was diluted with dichloromethane (60 mL) and washed with 5% potassium hydrogen sulfate solution twice and followed by diluted sodium bicarbonate solution two times. The organic layer was washed with water followed by brine and dried over sodium sulfate. The organic phase was evaporated to dryness in vacuo. The resultant residue was washed with diethyl ether a couple of times and dried. This produced the enkephalin conjugated small molecule 5 (0.12 g, 64% of yield) as a brown colored solid and used for the further reaction without purification.Preparation of compound 6: Prepared as described for compound 5 from 2 (0.1 g, 0.20 mmol, 1 equiv) N-((1-(((R)-5-amino-5,6,7,8-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl)methyl)piperidin-2-yl)methyl)-N-(3,4-difluorophenyl)propionamide and enkephalin peptide 4 (0.15 g, 0.23 mmol, 1 equiv) (Boc-Dmt-DAla-Gly-PheβAla-OH) afforded the compound 6 (0.14 g, 60% of yield) as a brown coloured solid and used for the further reaction without purification.Preparation of compound 7: Compound 7 was formed as a minor product during the preparation of compound 6 and we did not isolate the compound 7 and continued for the next reaction without further purification.Preparation of compound 8: To an ice-cold stirred solution of the enkephalin conjugated small molecule 5 (0.12 g) in dry dichloromethane (3 mL) was added 3 mL of trifluoroacetic acid. The resulting mixture was stirred for 2 h, and the solvent was stripped of under reduced pressure. The resultant residue was washed with diethyl ether a couple of times and dried afforded the final ligand 8 as a light brown colored solid. The crude final compound was purified by preparative RP-HPLC to give pure ligand 8 (50 mg, 41% of yield) as a white powder. ESI MS m/z 844 (MH)+. HRMS [M+H]+ 844.47534 (theoretical 844.4756); NMR (499 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.61 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 8.48–8.35 (m, 1H), 8.28 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 8.20–8.07 (m, 2H), 8.03 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.43–7.33 (m, 3H), 7.29–7.09 (m, 8H), 7.04 (dd, J = 8.8, 6.9 Hz, 2H), 6.74–6.66 (m, 2H), 4.90–4.82 (m, 1H), 4.67–4.58 (m, 1H), 4.58–4.42 (m, 1H), 4.42–4.26 (m, 2H), 4.16–4.05 (m, 3H), 4.06–3.82 (m, 4H), 3.82–3.72 (m, 1H), 3.66 (dd, J = 16.8, 5.3 Hz, 1H), 3.24–3.13 (m, 1H), 2.99–2.80 (m, 4H), 2.73–2.57 (m, 2H), 2.06–1.94 (m, 4H), 1.80–1.59 (m, 5H), 1.60–1.43 (m, 2H), 1.43–1.29 (m, 1H), 1.24 (dd, J = 7.0, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 1.08 (dd, J = 7.1, 1.7 Hz, 2H), 0.95–0.88 (m, 3H).Preparation of compound 9: Prepared as described for compound 8 from 6 (0.1 g) afforded the crude product 9. The final ligand 9 was isolated by preparative RP-HPLC (10–90% of acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA in water within 40 min) to give pure ligand 9 (39 mg, 38% of yield) as a white powder. ESI MS m/z 1001 (MNa)+. HRMS [M+H]+ 979.52441 (theoretical 979.5252); 1H NMR (499 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.73–9.39 (m, 1H), 8.36–8.28 (m, 3H), 8.24 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.17 (q, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (dd, J = 7.1, 2.6 Hz, 2H), 8.00 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.69–7.60 (m, 1H), 7.60–7.50 (m, 1H), 7.35–7.13 (m, 10H), 6.40 (s, 2H), 5.01–4.93 (m, 1H), 4.60 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 4.54–4.40 (m, 2H), 4.33–4.21 (m, 2H), 4.19–4.04 (m, 2H), 3.89–3.80 (m, 1H), 3.68 (dd, J = 16.8, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 3.59 (dd, J = 16.8, 5.9 Hz, 1H), 3.37–3.29 (m, 1H), 3.26–3.20 (m, 1H), 3.04–2.90 (m, 3H), 2.90–2.79 (m, 2H), 2.78–2.60 (m, 3H), 2.28 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.17 (s, 6H), 2.11–1.98 (m, 2H), 1.93–1.81 (m, 2H), 1.78–1.61 (m, 4H), 1.52 (q, J = 10.7, 7.9 Hz, 2H), 0.99–0.88 (m, 3H), 0.86 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H).Preparation of compound 10: Compound 10 was formed as a minor product during the preparation of compound 9. The final ligand 10 was isolated by preparative RP-HPLC (10–90% of acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA in water within 40 min) to give pure ligand 10 (10 mg) as a white powder. ESI MS m/ z 1516 (MH)+. HRMS [M+H]+2 758.89549 (theoretical 1515.78).-((N-phenylpropionamido)methyl)piperidin-1-ium (Compound 11) MS (ESI) m/z (M+H)+: 247. 1H NMR (499 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.70–8.61 (m, 1H), 8.59–8.47 (m, 1H), 7.52–7.41 (m, 4H), 7.41–7.36 (m, 1H), 4.10 (dd, J = 14.4, 8.5 Hz, 1H), 3.54 (dd, J = 14.4, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 3.34–3.23 (m, 1H), 3.14–3.01 (m, 1H), 2.85 (m, 1H), 2.11–1.89 (m, 2H), 1.77–1.64 (m, 3H), 1.64–1.49 (m, 1H), 1.44–1.33 (m, 2H). 0.90 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 174.51, 159.61, 159.32, 159.04, 158.75, 142.82, 130.31, 128.90, 128.55, 119.90, 117.57, 115.25, 112.92, 55.39, 51.66, 44.82, 40.50, 40.42, 40.33, 40.26, 40.17, 40.09, 40.00, 39.92, 39.83, 39.67, 39.50, 27.70, 26.56, 22.11, 21.82, 9.54.Preparation of compound 13: Prepared as described for compound 5 from 11 (0.1 g, 0.27 mmol, 1 equiv) (N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-2-ylmethyl)propionamide) and enkephalin peptide 3 (0.17 g, 0.27 mmol, 1 equiv) (Boc-Tyr-DAla-Gly-Phe-OH) afforded the compound 13 (0.15 g, 63% of yield) as a brown coloured solid and used for the further reaction without purification.Preparation of compound 14: Prepared as described for compound 5 from 11 (0.12 g, 0.34 mmol, 1 equiv) (N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-2-ylmethyl)propionamide) and enkephalin peptide 12 (0.2 g, mg, 0.34 mmol, 1 equiv) (Boc-Dmt-DAla-Gly-Phe-OH) afforded the compound 14 (0.16 g, 57% of yield) as a brown coloured solid and used for the further reaction without purification.Preparation of compound 15: Prepared as described for compound 5 from 11 (0.15 g, 0.41 mmol, 1 equiv) (N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-2-ylmethyl)propionamide) and enkephalin peptide 4 (0.27 g, 0.41 mmol, 1 equiv) (Boc-Dmt-DAla-Gly-Phe-βAla-OH) afforded the compound 15 (0.2 g, 55% of yield) as a brown coloured solid and used for the further reaction without purification.Preparation of compound 16: Prepared as described for compound 8 from 13 (0.1 g) afforded the crude product 16. The final ligand 16 was isolated by preparative RP-HPLC (10–90% of acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA in water within 40 min) to give pure ligand 16 as a white powder. ESI MS m/z 685 (MH)+. HRMS [M+H]+ 685.37063 (theoretical 685.37081); 1H NMR (499 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.41–9.27 (m, 1H), 8.60–8.45 (m, 1H), 8.39–8.20 (m, 1H), 8.18–7.93 (m, 3H), 7.46–7.30 (m, 3H), 7.30–7.13 (m, 6H), 7.09–6.93 (m, 3H), 6.70 (m, 2H), 4.91–4.80 (m, 1H), 4.75–4.61 (m, 1H), 4.45–4.28 (m, 1H), 4.28–4.09 (m, 1H), 4.09–3.45 (m, 6H), 3.40–3.25 (m, 1H), 2.95–2.79 (m, 3H), 2.79–2.56 (m, 1H), 1.95–1.80 (m, 1H), 1.65–1.30 (m, 5H), 1.31–1.11 (m, 2H), 1.13–0.99 (m, 3H), 0.92–0.75 (m, 3H).Preparation of compound 17: Prepared as described for compound 8 from 14 (0.12 g) afforded the crude product 17. The crude final ligand 17 was isolated by preparative RP-HPLC (10–90% of acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA in water within 40 min) to give pure ligand 17 as a white powder. ESI MS m/z 713 (MH)+. HRMS [M+H]+ 713.40194 (theoretical 713.40211); 1H NMR (499 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.39–8.28 (m, 3H), 8.16–8.00 (m, 2H), 7.45–7.30 (m, 3H), 7.29–7.12 (m, 6H), 7.08–7.02 (m, 1H), 6.41 (t, J = 2.5 Hz, 2H), 4.91–4.78 (m, 1H), 4.75–4.62 (m, 1H), 4.35–4.09 (m, 3H), 3.85–3.80 (m, 1H), 3.75–3.42 (m, 4H), 3.43–3.23 (m, 1H), 3.05–2.96 (m, 1H), 2.95–2.80 (m, 2H), 2.75–2.65 (m, 1H), 2.17 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 6H), 1.95–1.80 (m, 1H), 1.65–1.45 (m, 3H), 1.45–1.30 (m, 2H), 1.29–1.07 (m, 1H), 0.92–0.77 (m, 6H).Preparation of compound 18: Prepared as described for compound 8 from 15 (0.1 g, 0.10 mmol, 1 equiv) afforded the crude product 18. The final ligand 18 was isolated by preparative RP-HPLC (10–90% of acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA in water within 40 min) to give pure ligand 18 as a white powder. ESI MS m/z 784 (MH)+. HRMS [M+H]+ 784.4391 (theoretical 784.4392); 1H NMR (499 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.31 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 3H), 8.12–7.96 (m, 4H), 7.46–7.40 (m, 2H), 7.36–7.28 (m, 2H), 7.26–7.13 (m, 6H), 6.41 (s, 2H), 4.73 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.46–4.40 (m, 1H), 4.29–4.18 (m, 1H), 4.18–4.07 (m, 1H), 4.05–3.96 (m, 1H), 3.89–3.52 (m, 7H), 3.45 (d, J = 13.9 Hz, 1H), 3.30–3.18 (m, 1H), 3.17–3.05 (m, 2H), 3.00 (dd, J = 13.8, 11.3 Hz, 1H), 2.95–2.82 (m, 2H), 2.79–2.70 (m, 1H), 2.17 (s, 6H), 1.70–1.46 (m, 4H), 1.41–1.21 (m, 2H), 0.95–0.80 (m, 6H)

- 22.Lee YS, Nyberg J, Moye S, Agnes RS, Davis P, Ma SW, Lai J, Porreca F, Vardanyan R, Hruby VJ. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:2161. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.01.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee YS, Petrov R, Park C, Ma SW, Davis P, Lai J, Porreca F, Hruby VJ. J Med Chem. 2007;50:5528. doi: 10.1021/jm061465o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deekonda S, Wugalter L, Rankin D, Largent-Milnes TM, Davis P, Wang Y, Bassirirad NM, Lai J, Kulkarni V, Vanderah TW, Porreca F, Hruby VJ. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2015;25:4683. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.07.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dan P, Birgitte EL, Gordon M, Ostergaard NE, Paul RJ. 2007093603. WO. 2007

- 26.Gregory CD, Liming S, James HR, Brian AM, Xinhe W, Fengjian W, Thomas BD. 200071518. WO. 2000

- 27.Lee K, Jung WH, Park CW, Hong CY, Kim IC, Kim S, Oh YS, Kwon OH, Lee SH, Park HD, Kim SW, Lee YH, Yoo YJ. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998;18:2563. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00456-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hagmann WK. J Med Chem. 2008;51:4359. doi: 10.1021/jm800219f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misicka A, Lipkowski AW, Horvath R, Davis P, Kramer TH, Yamamura HI, Hruby VJ. Life Sci. 1992;51:1025. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90501-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kramer TH, Davis P, Hruby VJ, Burks TF, Porreca F. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;266:577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yaksh TL, Rudy TA. Physiol Behav. 1976;17:1031. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(76)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. Pain. 1988:3277. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.