Abstract

Premise of the study:

We report the complete sequence of the chloroplast genome of Capsicum frutescens (Solanaceae), a species of chili pepper.

Methods and Results:

Using an Illumina platform, we sequenced the chloroplast genome of C. frutescens. The total length of the genome is 156,817 bp, and the overall GC content is 37.7%. A pair of 25,792-bp inverted repeats is separated by small (17,853 bp) and large (87,380 bp) single-copy regions. The C. frutescens chloroplast genome encodes 132 unique genes, including 87 protein-coding genes, 37 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, and eight ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes. Of these, seven genes are duplicated in the inverted repeats and 12 genes contain one or two introns. Comparative analysis with the reference chloroplast genome revealed 125 simple sequence repeat motifs and 34 variants, mostly located in the noncoding regions.

Conclusions:

The complete chloroplast genome sequence of C. frutescens reported here is a valuable genetic resource for Capsicum species.

Keywords: Capsicum frutescens, chili pepper, chloroplast genome, next-generation sequencing, Solanaceae

A chloroplast is an organelle with its own genome encoding a number of chloroplast-specific components (Sugiura et al., 1998). Owing to its tractable size and high level of conservation, the chloroplast genome can be used to characterize genetic relationships among species. Furthermore, plant taxonomists have widely adopted the sequence variability of two loci in land plants, consisting of portions of the chloroplast rbcL and matK genes, as an effective DNA barcode (Vijayan and Tsou, 2010). Chloroplast DNA contains many of the genes necessary for proper functioning of the organelle. The analysis of chloroplast DNA sequences has proven useful in studying plant evolution (Shaw et al., 2007), and the field of chloroplast genome characterization is growing rapidly (Timmis et al., 2004). The size of the genome, which has been determined for a number of plants and algae, ranges from 85 to 292 kbp. The complete DNA sequences of several different chloroplast genomes of plants and algae have been reported. Many chloroplast DNAs contain two inverted repeats (IRs), which separate a large single-copy region (LSC) from a small single-copy region (SSC) (Palmer and Thompson, 1982). The IRs vary in length from 4 to 25 kbp (Robinson et al., 2009).

Capsicum frutescens L. (Solanaceae), a name that is generally applied to all cultivated peppers in the United States, is also known as C. annuum L. (Smith and Heiser, 1951). Cultivars of C. frutescens can be annual or short-lived perennial plants. The flowers have a greenish white or greenish yellow corolla, and they are either insect- or self-pollinated. The fruit is usually very pungent, growing to 1.0–8.0 cm long and 0.6–3.0 cm in diameter (Smith and Heiser, 1951). The fruit is typically pale yellow as it matures to a bright red, but it can also be other colors (Heiser and Smith, 1953; Stummel and Bosland, 2006). More recently, C. frutescens has been bred to produce ornamental strains with a large number of erect peppers growing in colorful ripening patterns (Stummel and Bosland, 2006). Capsicum frutescens likely originated in South or Central America (Heiser, 1979; Clement et al., 2010) and spread quickly throughout the tropical and subtropical regions in this area, where it still grows wild today (Purseglove, 1976). It is also believed that C. frutescens is the ancestor of C. chinense Jacq. (Bosland, 1996; Basu et al., 2003).

In this study, using Illumina technology, the complete chloroplast genome of C. frutescens was sequenced, assembled, annotated, and mined for simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers and for single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and insertion/deletion (indel) variants. The resultant data have been made publicly available as a resource for genetic information for Capsicum L. species, which will facilitate investigations into genetic variation and phylogenetic relationships of closely related Capsicum species.

METHODS AND RESULTS

For this study, C. frutescens seeds (accession no. IT158639) were obtained from the National Agrobiodiversity Center, Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea. Seeds were germinated and grown in a greenhouse, fresh leaves were collected from 40-d-old seedlings, and DNA was extracted using a DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, California, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions to construct chloroplast DNA libraries. An Illumina paired-end DNA library (average insert size of 500 bp) was constructed using the Illumina TruSeq library preparation kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, San Diego, California, USA).

The library was sequenced with 2 × 300 bp on the MiSeq instrument at LabGenomics (http://www.labgenomics.co.kr/). Prior to chloroplast de novo assembly, low-quality sequences (quality score < 20; Q20) were filtered out, and the remaining high-quality reads were assembled using the CLC Genome Assembler (version beta 4.6; CLC bio, Aarhus, Denmark) with a minimum overlap size of 200 bp and maximum bubble size of 50 bp for the de Bruijn graph. Chloroplast contigs were selected from the initial assembly by performing a BLAST (version 2.2.31) search against the reference chloroplast genome of C. annuum (GenBank accession NC_018552) using CLC software with parameters of 0.5 for fraction, 0.8 for similarity, and 200–600 bp of overlap size (Jo et al., 2011). The selected chloroplast contigs were merged into a total of four contigs, and iterative contig extensions were performed to construct a complete C. frutescens chloroplast genome by mapping raw reads to the contigs. Dual Organellar GenoMe Annotator (DOGMA; Wyman et al., 2004) and CpGAVAS (Liu et al., 2012) were used to annotate the chloroplast genome. All transfer RNA (tRNA) genes were amended with tRNAscan-SE (Lowe and Eddy, 1997). OGDRAW (Lohse et al., 2007) was used to produce a map of the genome.

Sputnik software (Cardle et al., 2000) was used to find the SSR markers present in the chloroplast genome of C. frutescens. It uses a recursive algorithm to search for repeats with lengths between two and five, and finds perfect, compound, and imperfect repeats. Sputnik has been applied for SSR identification in many species, including Arabidopsis and barley (Cardle et al., 2000). To identify SNP and indel variants in the C. frutescens chloroplast genome, we used BWA (Li and Durbin, 2009) with ‘mem’ command line options ‘-k19 –w100 –d100 –r1.5 –y20 –c500 –D0.5 –W0 –m50’ and SAMtools (Li et al., 2009) software with ‘mpileup’ command line options ‘-uf –d250 -q0 –e20 –h100 –L250 –m1 –o40.’ A more detailed method is described at http://samtools.sourceforge.net/mpileup.shtml.

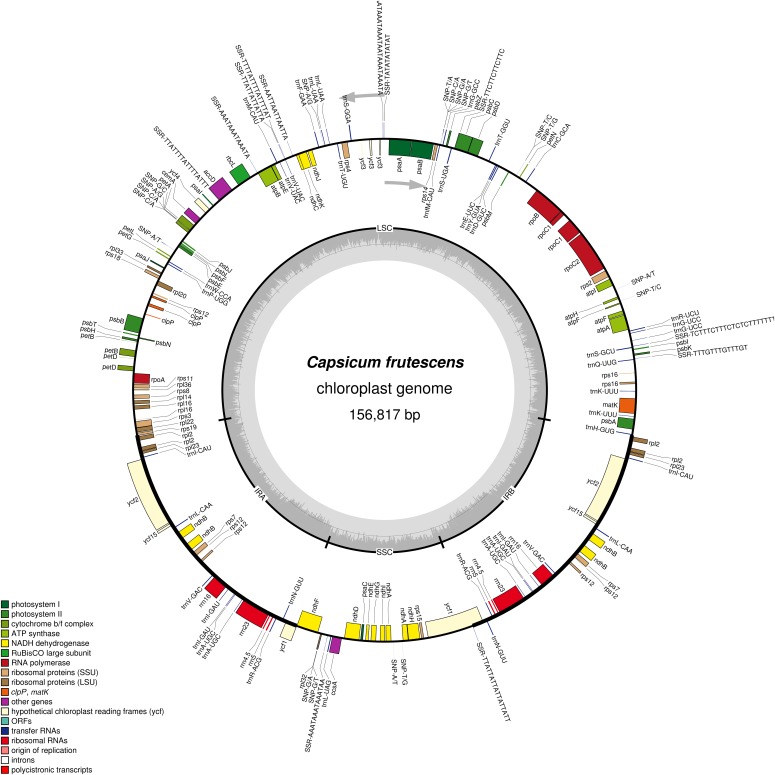

Illumina paired-end (2 × 300 bp) sequencing produced a total of 8,272,114 paired-end reads, with an average fragment length of 256 bp, which were then analyzed to generate 1,796,432,923 bp of sequence. The results contain 31,772,592 mapped nucleotides with an average coverage of 202× on the chloroplast genome. Contig alignment and scaffolding based on paired-end data resulted in a complete circular C. frutescens chloroplast genome sequence (Fig. 1). The chloroplast genome of C. frutescens has been deposited in GenBank (accession no. KR078312; National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI]). It has a total length of 156,817 bp and is composed of an LSC of 87,380 bp, two IRs of 25,792 bp, and an SSC of 17,853 bp. The overall GC content of the C. frutescens chloroplast genome is 37.7%, with the IRs having a higher GC content (43.1%) than the LSC (35.7%) and SSC (32.0%) due to the presence of GC-rich ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes. The C. frutescens chloroplast genome encodes 132 unique genes (Appendix 1), including 87 protein-coding genes, 37 tRNA genes, and eight rRNA genes. Seven of these genes are duplicated in the IR regions, nine genes (rps16, atpF, rpoC1, petB, petD, rpl16, rpl2 (IR), ndhB (IR), ndhA) and six tRNA genes contain one intron, and two genes (clpP, rps12) and one ycf (ycf3) contain two introns (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Gene map of the Capsicum frutescens chloroplast genome. Genes drawn inside the circle are transcribed clockwise, while those drawn outside are transcribed counterclockwise (marked with two arrows). Different functional gene groups are color-coded. Variation in the GC content of the genome is shown in the middle circle. The map was drawn using OGDRAW version 1.2 (Lohse et al., 2007).

The size of the C. frutescens chloroplast genome (156,817 bp) was larger than reported for Capsicum species such as C. annuum var. glabriusculum (Dunal) Heiser & Pickersgill (GenBank accession no. KJ619462) and C. annuum (GenBank accession no. NC_018552). The lengths of the LSC and IRs in C. frutescens differed from those in the other two species and contributed to the variation of chloroplast genome size. For example, the C. frutescens chloroplast genome was 36 bp longer than the reported C. annuum chloroplast genome and 205 bp longer than the C. annuum var. glabriusculum chloroplast genome. Furthermore, the SSC and IR regions of C. frutescens were 3 and 9 bp longer, respectively, and the LSC region was 14 bp shorter and 167 bp longer, respectively, than those of the previously reported chloroplast genomes. The average GC content in the C. frutescens chloroplast genome is 37.7%, similar to other Capsicum species.

The organization and gene order of the Capsicum chloroplast genome exhibited the general chloroplast genome structure seen in angiosperms (Sugiura, 1992). The Capsicum chloroplast genome contains 132 genes (Appendix 2), of which there were eight rRNA genes, 37 tRNA genes, 21 ribosomal subunit genes (12 small subunit and nine large subunit), and four DNA-directed RNA polymerase genes. Forty-six genes were involved in photosynthesis, of which 11 encoded subunits of the NADH-oxidoreductase, seven for photosystem I, 15 for photosystem II, six for the cytochrome b6/f complex, six for different subunits of ATP synthase, and one for the large chain of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO). Five genes were involved in different functions, and three genes were of unknown function. As shown in Fig. 1 and Appendix 2, genome organization appeared to be more conserved with unique gene sequences, as discovered previously in Capsicum species (Jo et al., 2011; Zeng et al., 2014; Raveendar et al., 2015a). However, in this newly determined chloroplast genome, we found 132 predicted genes and size variations were observed in the IR and LSC regions.

A total of 125 potential SSRs motifs were identified, located mostly in the noncoding regions (Table 1); of these, the majority belonged to tetranucleotide (50%) and trinucleotide (26%) repeats. All other types of SSRs, such as di- and pentanucleotide motifs, were relatively low (25%). The majority of tetranucleotide SSRs had the AAAT/AATA/ATAA motif, followed by those with the ATAA/TAAA/AAAT motif; the TTTG/TTGT/TGTT, TCTT/CTTT/TTTC, and AATT/ATTA/TTAA motifs were found with similar frequency (7.2%). Two different repeats—those with the TTTTA/TTTAT/TTATT and TTATT/TATTT/ATTTT motifs—were identified among pentanucleotide SSRs. The TTC/TCT/CTT and TTA/TAT/ATT motifs were identified among the trinucleotide SSRs, but only the TA/AT motif was identified for the dinucleotide SSRs (Table 1). In total, 125 potential SSRs motifs were identified in the 156.8-kb sequence of the Capsicum chloroplast genome. Hence, the observed frequency of SSRs motifs was approximately one per 1250 bp of chloroplast genome.

Table 1.

SSR candidates of the Capsicum frutescens chloroplast genome.

| SSR type | SSR abundances | Percentage abundance (%) |

| Dinucleotide | ||

| TA/AT | 9 | 7.2 |

| Trinucleotide | ||

| TTC/TCT/CTT | 9 | 7.2 |

| TTA/TAT/ATT | 23 | 18.4 |

| Tetranucleotide | ||

| TTTG/TTGT/TGTT | 9 | 7.2 |

| TCTT/CTTT/TTTC | 9 | 7.2 |

| ATAA/TAAA/AAAT | 16 | 12.8 |

| AATT/ATTA/TTAA | 9 | 7.2 |

| AAAT/AATA/ATAA | 19 | 15.2 |

| Pentanucleotide | ||

| TTTTA/TTTAT/TTATT | 11 | 8.8 |

| TTATT/TATTT/ATTTT | 11 | 8.8 |

| Total | 125 | 100 |

Comparison of the C. frutescens chloroplast genome sequence with the reference chloroplast sequence of C. annuum revealed a total of 34 mutations (18 SNPs and 16 indels), with 15 of these variants involving more than one nucleotide (Table 2 and 3). Among the detected variants, six SNPs and two indels were observed in the coding region of the chloroplast genome. Among these SNPs and indels, there were 29 and five mutations located in the LSC and SSC regions, respectively. These molecular markers will facilitate studies of genetic diversity, population genetic structure, and sustainable conservation for C. frutescens.

Table 2.

SNP markers of the Capsicum frutescens chloroplast genome.

| No. | REF (C. annuum) | ALT (C. frutescens) | Coding region | QUAL | Region |

| 1 | T | C | noncoding region | 222 | LSC |

| 2 | A | T | noncoding region | 222 | LSC |

| 3 | T | G | noncoding region | 4.77 | LSC |

| 4 | T | C | noncoding region | 19.1 | LSC |

| 5 | G | T | noncoding region | 222 | LSC |

| 6 | G | A | noncoding region | 222 | LSC |

| 7 | C | A | noncoding region | 222 | LSC |

| 8 | T | A | noncoding region | 222 | LSC |

| 9 | A | G | noncoding region | 222 | LSC |

| 10 | G | C | gene (petA) | 222 | LSC |

| 11 | A | G | gene (petA) | 222 | LSC |

| 12 | C | A | gene (petA) | 222 | LSC |

| 13 | C | A | gene (petA) | 222 | LSC |

| 14 | A | T | noncoding region | 222 | LSC |

| 15 | G | A | gene (rpl32) | 164 | SSC |

| 16 | G | T | gene (rpl32) | 124 | SSC |

| 17 | A | T | noncoding region | 222 | SSC |

| 18 | T | G | noncoding region | 222 | SSC |

Note: ALT = alteration; LSC = large single-copy; QUAL = Phred-scaled quality score; REF = reference; SSC = small single-copy.

Table 3.

Indel markers of the Capsicum frutescens chloroplast genome.

| No. | REF (C. annuum) | ALT (C. frutescens) | Coding region | QUAL | Region |

| 1 | ATTTTTTTTT | ATTTTTTTTTT, ATTTTTTTTTTT | noncoding region | 48.5 | LSC |

| 2 | TAAAAAA | TAAAAAAA | noncoding region | 178 | LSC |

| 3 | GAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA | GAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA, GAAAAAAAAAAA, GAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA | noncoding region | 18.5 | LSC |

| 4 | CTTTTTT | CTTTTTTT | noncoding region | 152 | LSC |

| 5 | TCAACTCATTTTA | T | noncoding region | 214 | LSC |

| 6 | TATTTTTAATTTTAATTTT | TAT | noncoding region | 217 | LSC |

| AATATATTTTAATTTTAAT | |||||

| ATAAATAAATAATTTTAAT | |||||

| ATATTAATATAAATAAATA | |||||

| AATAAT | |||||

| 7 | CAAAAAAAAAA | CAAAAAAAAAAA, CAAAAAAAAAAAA, CAAAAAAAA | noncoding region | 65.5 | LSC |

| 8 | ATTTTTTTTT | ATTTTTTTTTT, ATTTTTTTTTTT | noncoding region | 68.5 | LSC |

| 9 | TAAAAAAAAAA | TAAAAAAAAAAA, TAAAAAAAAAAAA | noncoding region | 48.5 | LSC |

| 10 | TCCGGTAAAGACTCCGG | TCCGGTAAAGACGCCGGTAAAGA | gene (rpl20) | 218 | LSC |

| TAAAGACTCCGGTAAAGAC | CTCCGGTAAAGACTCCGGTAAAGAC | ||||

| 11 | GTTTTTTTT | GTTTTTTTTT, GTTTTTTTTTT | noncoding region | 94.5 | LSC |

| 12 | GAAAAAAA | GAAAAAA | noncoding region | 66.5 | LSC |

| 13 | GAAAAAAAA | GAAAAAAAAA, GAAAAAAAAAA | noncoding region | 90.5 | LSC |

| 14 | CTTTT | CTTTTT | noncoding region | 214 | LSC |

| 15 | ATTCTTATTTTTT | ATTATTTTTT | gene (rps19) | 203 | LSC |

| 16 | TCCCCC | TCCCCCC | noncoding region | 185 | SSC |

Note: ALT = alteration; LSC = large single-copy; QUAL = Phred-scaled quality score; REF = reference; SSC = small single-copy.

The size of the C. frutescens chloroplast genome identified here is more closely related to that of C. annuum var. glabriusculum reported previously (Raveendar et al., 2015b). Moreover, the C. frutescens chloroplast genome has similar genome organization, gene order, gene sizes, and GC content, with only SNPs/indels variation. It has been reported that C. annuum var. glabriusculum is considered the wild parental species of the cultivated C. annuum (Votava et al., 2002; Aguilar-Meléndez et al., 2009; González-Jara et al., 2011).

CONCLUSIONS

We provide here the complete chloroplast genome sequence of C. frutescens, a cultivated pepper in the United States. Availability of this sequence and the recently determined C. annuum chloroplast genome sequence (GenBank accession no. NC_018552) enables us to assess genome-wide mutational dynamics within the genus Capsicum. The chloroplast genome possesses similar genome organization, gene order, gene sizes, and GC content, with only SNPs/indels variation having been revealed. It is difficult to get accurate phylogenies and effective species discrimination using a small number of plastid genes in evolutionarily young lineages (Ruhsam et al., 2015). Therefore, complete plastid genome sequencing provides a solution to this problem. Availability of this sequence can enable researchers to design conserved primers to sequence new genomic regions that could provide useful phylogenetic information for closely related species. Moreover, the structural details of this C. frutescens chloroplast genome join the growing database of Capsicum species, which can facilitate investigations into gene expression and genetic variation of these crop species.

Appendix 1.

General features of the Capsicum frutescens chloroplast genome.

| Chloroplast genome feature | Quantity |

| Genome size (bp) | 156,817 |

| GC content (%) | 37.7 |

| Total no. of genes | 132 |

| Protein-coding genes | 87 |

| rRNA genes | 8 |

| tRNA genes | 37 |

| Genes duplicated in IR regions | 7 |

| Total introns | 12 |

| Single intron (gene) | 9 |

| Double introns (gene) | 3 |

| Single intron (tRNA) | 6 |

Appendix 2.

Genes present in the Capsicum frutescens chloroplast genome.

| Chloroplast genome feature | Gene products |

| Photosystem I | psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ, ycf32, ycf4 |

| Photosystem II | psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbN, psbT, psbZ |

| Cytochrome b6/f | petA, petB1, petD1, petG, petL, petN |

| ATP synthase | atpA, atpB, atpE, atpF1, atpH, atpI |

| RuBisCO | rbcL |

| NADH oxidoreductase | ndhA1, ndhB1,3, ndhC, ndhD, ndhE, ndhF, ndhG, ndhH, ndhI, ndhJ, ndhK |

| Large subunit ribosomal proteins | rpl21,3, rpl14, rpl161, rpl20, rpl22, rpl233, rpl32, rpl33, rpl36 |

| Small subunit ribosomal proteins | rps2, rps3, rps4, rps73, rps8, rps11, rps122,3,4, rps14, rps15, rps161, rps18, rps19 |

| RNA polymerase | rpoA, rpoB, rpoC11, rpoC2 |

| Unknown function protein-coding gene | ycf13, ycf23, ycf153 |

| Other genes | accD, ccsA, cemA, clpP2, matK |

| Ribosomal RNAs | rrn163, rrn233, rrn4.53, rrn53 |

| Transfer RNAs | trnA-UGC1,3, trnC-GCA, trnD-GUC, trnE-UUC, trnF-GAA, trnG-UCC1, trnG-GCC, trnH-GUG, trnI-CAU3, trnI-GAU1,3, trnK-UUU1, trnL-UAA1, trnL-UAG, trnL-CAA3, trnfM-CAU, trnM-CAU, trnN-GUU3, trnP-UGG, trnQ-UUG, trnR-ACG3, trnR-UCU, trnS-GCU, trnS-GGA, trnS-UGA, trnT-GGU, trnT-UGU, trnV-UAC1, trnV-GAC3, trnW-CCA, trnY-GUA |

Gene containing a single intron.

Gene containing two introns.

Two gene copies in IRs.

Transsplicing gene.

LITERATURE CITED

- Aguilar-Meléndez A., Morrell P. L., Roose M. L., Kim S. C. 2009. Genetic diversity and structure in semiwild and domesticated chiles (Capsicum annuum; Solanaceae) from Mexico. American Journal of Botany 96: 1190–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S. K., De A. K., De A. 2003. Capsicum: Historical and botanical perspectives. In A. K. De , Capsicum: The genus Capsicum, 1–15. CRC Press, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Bosland P. W. 1996. Capsicums: Innovative uses of an ancient crop. In J. Janick , Progress in new crops, 479–487. ASHS Press, Arlington, Virginia, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cardle L., Ramsay L., Milbourne D., Macaulay M., Marshall D., Waugh R. 2000. Computational and experimental characterization of physically clustered simple sequence repeats in plants. Genetics 156: 847–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement C. R., De Cristo-Araújo M., Coppens D’Eeckenbrugge G., Alves Pereira A., Picanço-Rodrigues D. 2010. Origin and domestication of native Amazonian crops. Diversity (Basel) 2: 72–106. [Google Scholar]

- González-Jara P., Moreno-Letelier A., Fraile A., Piñero D., García-Arenal F. 2011. Impact of human management on the genetic variation of wild pepper, Capsicum annuum var. glabriusculum. PLoS ONE 6: e28715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiser C. B. 1979. Origins of some cultivated new world plants. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 10: 309–326. [Google Scholar]

- Heiser C. B., Smith P. G. 1953. The cultivated Capsicum peppers. Economic Botany 7: 214–227. [Google Scholar]

- Jo Y. D., Park J., Kim J., Song W., Hur C. G., Lee Y. H., Kang B. C. 2011. Complete sequencing and comparative analyses of the pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) plastome revealed high frequency of tandem repeats and large insertion/deletions on pepper plastome. Plant Cell Reports 30: 217–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25: 1754–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., Homer N., Marth G., et al. 2009. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25: 2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Shi L., Zhu Y., Chen H., Zhang J., Lin X., Guan X. 2012. CpGAVAS, an integrated web server for the annotation, visualization, analysis, and GenBank submission of completely sequenced chloroplast genome sequences. BMC Genomics 13: 715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse M., Drechsel O., Bock R. 2007. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW): A tool for the easy generation of high-quality custom graphical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes. Current Genetics 52: 267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe T. M., Eddy S. R. 1997. . tRNAscan-SE: A program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Research 25: 955–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer J. D., Thompson W. F. 1982. Chloroplast DNA rearrangements are more frequent when a large inverted repeat sequence is lost. Cell 29: 537–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purseglove J. 1976. The origins and migrations of crops in tropical Africa. In J. R. Harlan , Origins of African plant domestication, 291–309. Mouton De Gruyter, The Hague, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Raveendar S., Jeon Y.-A., Lee J.-R., Lee G.-A., Lee K. J., Cho G.-T., Maa K.-H., Lee S.-Y., Chung J.-W. 2015a. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Korean landrace “Subicho” pepper (Capsicum annuum var. annuum). Plant Breeding and Biotechnology 3: 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Raveendar S., Na Y. W., Lee J. R., Shim D., Ma K. H., Lee S. Y., Chung J. W. 2015b. The complete chloroplast genome of Capsicum annuum var. glabriusculum using Illumina sequencing. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 20: 13080–13088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D. G., Aronsson H., Sandelius A. S. 2009. The chloroplast: Interactions with the environment. Springer, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhsam M., Rai H. S., Mathews S., Ross T. G., Graham S. W., Raubeson L. A., Mei W., et al. 2015. Does complete plastid genome sequencing improve species discrimination and phylogenetic resolution in Araucaria? Molecular Ecology Resources 15: 1067–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J., Lickey E. B., Schilling E. E., Small R. L. 2007. Comparison of whole chloroplast genome sequences to choose noncoding regions for phylogenetic studies in angiosperms: The tortoise and the hare III. American Journal of Botany 94: 275–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P. G., Heiser C. B., Jr 1951. Taxonomic and genetic studies on the cultivated peppers, Capsicum annuum L. and C. frutescens L. American Journal of Botany 38: 362–368. [Google Scholar]

- Stummel J. R., Bosland P. 2006. Ornamental pepper: Capsicum annuum In N. O. Anderson , Flower breeding and genetics: Issues, challenges, and opportunities for the 21st century, 561–599. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura M. 1992. The chloroplast genome. Plant Molecular Biology 19: 149–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura M., Hirose T., Sugita M. 1998. Evolution and mechanism of translation in chloroplasts. Annual Review of Genetics 32: 437–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmis J. N., Ayliffe M. A., Huang C. Y., Martin W. 2004. Endosymbiotic gene transfer: Organelle genomes forge eukaryotic chromosomes. Nature Reviews. Genetics 5: 123–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan K., Tsou C. H. 2010. DNA barcoding in plants: Taxonomy in a new perspective. Current Science (India) 99: 1530–1541. [Google Scholar]

- Votava E., Nabhan G., Bosland P. 2002. Genetic diversity and similarity revealed via molecular analysis among and within an in situ population and ex situ accessions of chiltepín (Capsicum annuum var. glabriusculum). Conservation Genetics 3: 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wyman S. K., Jansen R. K., Boore J. L. 2004. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics 20: 3252–3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng F. C., Gao C. W., Gao L. Z. 2014. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of American bird pepper (Capsicum annuum var. glabriusculum). Mitochondrial DNA Part A 27: 724–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]