Abstract

T cell infiltration of solid tumors is associated with favorable patient outcomes, yet the mechanisms underlying variable immune responses between individuals are not well understood. One possible modulator could be the intestinal microbiota. We compared melanoma growth in mice harboring distinct commensal microbiota and observed differences in spontaneous antitumor immunity, which were eliminated upon cohousing or after fecal transfer. Sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA identified Bifidobacterium as associated with the antitumor effects. Oral administration of Bifidobacterium alone improved tumor control to the same degree as programmed cell death protein 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1)–specific antibody therapy (checkpoint blockade), and combination treatment nearly abolished tumor outgrowth. Augmented dendritic cell function leading to enhanced CD8+ T cell priming and accumulation in the tumor microenvironment mediated the effect. Our data suggest that manipulating the microbiota may modulate cancer immunotherapy.

Harnessing the host immune system constitutes a promising cancer therapeutic because of its potential to specifically target tumor cells although limiting harm to normal tissue. Enthusiasm has been fueled by recent clinical success, particularly with antibodies that block immune inhibitory pathways, specifically CTLA-4 and the axis between programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligand 1 (PD-L1) (1, 2). Clinical responses to these immunotherapies are more frequent in patients who show evidence of an endogenous T cell response ongoing in the tumor microenvironment before therapy (3–6). However, the mechanisms that govern the presence or absence of this phenotype are not well understood. Theoretical sources of interpatient heterogeneity include host germ-line genetic differences, variability in patterns of somatic alterations in tumor cells, and environmental differences.

The gut microbiota plays an important role in shaping systemic immune responses (7–9). In the cancer context, a role for intestinal microbiota in mediating immune activation in response to chemotherapeutic agents has been demonstrated (10, 11). However, it is not known whether commensal microbiota influence spontaneous immune responses against tumors and thereby affect the therapeutic activity of immunotherapeutic interventions, such as anti–PD-1/PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs).

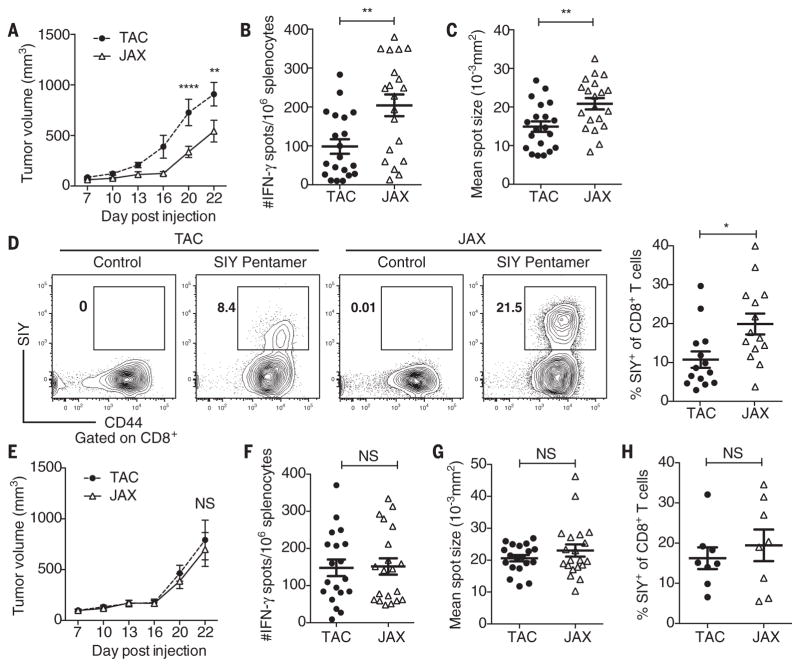

To address this question, we compared subcutaneous B16.SIY melanoma growth in genetically similar C57BL/6 mice derived from two different mouse facilities, Jackson Laboratory (JAX) and Taconic Farms (TAC), which have been shown to differ in their commensal microbes (12). We found that JAX and TAC mice exhibited significant differences in B16.SIY melanoma growth rate, with tumors growing more aggressively in TAC mice (Fig. 1A). This difference was immune-mediated: Tumor-specific T cell responses (Fig. 1, B and C) and intratumoral CD8+ T cell accumulation (Fig. 1D) were significantly higher in JAX than in TAC mice. To begin to address whether this difference could be mediated by commensal microbiota, we cohoused JAX and TAC mice before tumor implantation. We found that cohousing ablated the differences in tumor growth (Fig. 1E) and immune responses (Fig. 1, F to H) between the two mouse populations, which suggested an environmental influence. Cohoused TAC and JAX mice appeared to acquire the JAX phenotype, which suggested that JAX mice may be colonized by commensal microbes that dominantly facilitate antitumor immunity.

Fig. 1. Differences in melanoma outgrowth and tumor-specific immune responses between C57BL/6 JAX and TAC mice are eliminated when mice are cohoused.

(A) B16. SIY tumor growth kinetics in newly arrived JAX and TAC mice. (B) IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISPOT) in tumor-bearing JAX and TAC mice 7 days after tumor inoculation. (C) Mean size of IFN-γ spots (10−3 mm2). (D) Percentage of SIY+ T cells of total CD8+ T cells within the tumor of JAX and TAC mice as determined by flow cytometry 21 days after tumor inoculation. Representative plots (left), quantification (right). (E) B16.SIY tumor growth kinetics in JAX and TAC mice cohoused for 3 weeks before tumor inoculation. (F) Number of IFN-γ spots/106 splenocytes in tumor-bearing JAX and TAC mice cohoused for 3 weeks before tumor inoculation. (G) Mean size of IFN-γ spots (10−3 mm2). (H) Percentage of SIY+ T cells of total CD8+ T cells within the tumor of JAX and TAC mice cohoused for 3 weeks before tumor inoculation. Means ± SEM combined from six independent experiments, analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Sidak’s correction for multiple comparisons (A) and (E), or individual mice with means ± SEM combined from four (B), (C), (F), (G) or three (D) and (H) independent experiments, analyzed by Student’s t test; five mice per group per experiment; *P < 0.005, **P < 0.01; NS, not significant.

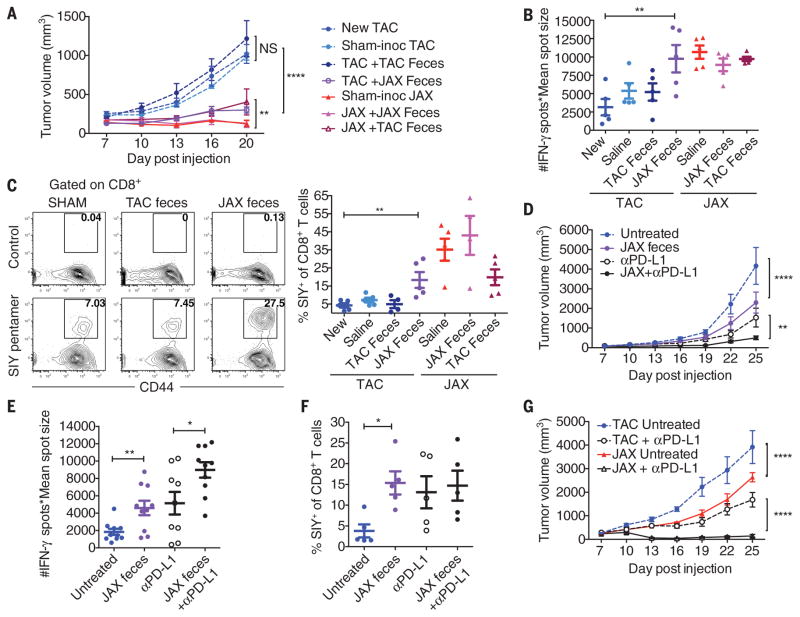

To directly test the role of commensal bacteria in regulating antitumor immunity, we transferred JAX or TAC fecal suspensions into TAC and JAX recipients by oral gavage before tumor implantation (fig. S1A). We found that prophylactic transfer of JAX fecal material, but not saline or TAC fecal material, into TAC recipients was sufficient to delay tumor growth (Fig. 2A) and to enhance induction and infiltration of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2, B and C, and fig. S1B), which supported a microbe-derived effect. Reciprocal transfer of TAC fecal material into JAX recipients had a minimal effect on tumor growth rate and anti-tumor T cell responses (Fig. 2, A to C, and fig. S1B), consistent with the JAX-dominant effects observed upon cohousing.

Fig. 2. Oral administration of JAX fecal material to TAC mice enhances spontaneous antitumor immunity and response to αPD-L1 mAb therapy.

(A) B16.SIY tumor growth in newly arrived TAC mice, TAC and JAX mice orally gavaged with phosphate-buffered saline or TAC or JAX fecal material before tumor implantation. (B) Number of IFN-γ spots × mean spot size (10−3 mm2), determined by ELISPOT 7 days after tumor inoculation. (C) Percentage of SIY+ CD8+ Tcells within the tumor of TAC and JAX mice treated as in (A), 21 days after tumor inoculation. Representative plots (left), quantification (right). (D) B16.SIY tumor growth in TAC mice, untreated or treated with JAX fecal material 7 and 14 days after tumor implantation, αPD-L1 mAb 7, 10, 13, and 16 days after tumor implantation, or both regimens. (E) IFN-γ ELISPOT assessed 5 days after start of treatment. (F) Percentage of tumor-infiltrating SIY+ CD8+ Tcells, determined by flow cytometry 14 days after start of treatment. (G) B16.SIY tumor growth kinetics in TAC and JAX mice, untreated or treated with αPD-L1 mAb 7, 10, 13, and 16 days after tumor implantation. Means ± SEM analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s (A) or Tukey’s (D) and (G) correction for multiple comparisons; or individual mice with means ± SEM analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons (B), (C), (E), and (F); data are representative of (A) to (C), (F), and (G) or combined from (D) and (E) two to four independent experiments; five mice per group per experiment; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant.

To test whether manipulation of the microbial community could be effective as a therapy, we administered JAX fecal material alone or in combination with antibodies targeting PD-L1 (αPD-L1) to TAC mice bearing established tumors. Transfer of JAX fecal material alone resulted in significantly slower tumor growth (Fig. 2D), accompanied by increased tumor-specific T cell responses (Fig. 2E) and infiltration of antigen-specific T cells into the tumor (Fig. 2F), to the same degree as treatment with systemic αPD-L1 mAb. Combination treatment with both JAX fecal transfer and αPD-L1 mAb improved tumor control (Fig. 2D) and circulating tumor antigen–specific T cell responses (Fig. 2E), although there was little additive effect on accumulation of activated T cells within the tumor microenvironment (Fig. 2F). Consistent with these results, αPD-L1 therapy alone was significantly more efficacious in JAX mice compared with TAC mice (Fig. 2G), which paralleled improved antitumor T cell responses (fig. S1C). These data indicate that the commensal microbial composition can influence spontaneous antitumor immunity, as well as a response to immunotherapy with αPD-L1 mAb.

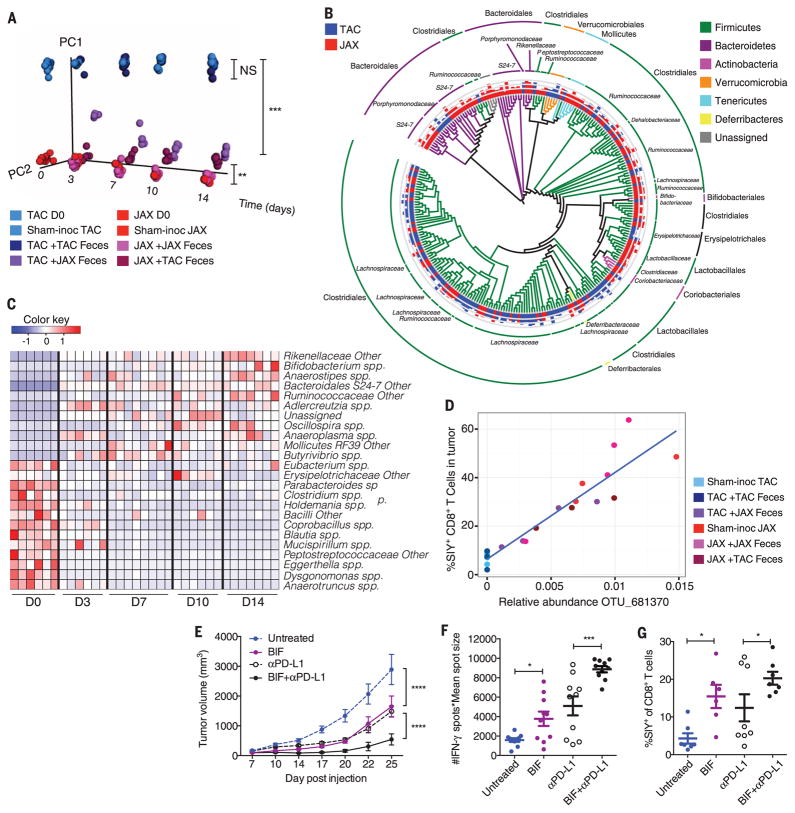

To identify specific bacteria associated with improved antitumor immune responses, we monitored the fecal bacterial content over time of mice that were subjected to administration of fecal permutations, using the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) miSeq Illumina platform. Principal coordinate analysis revealed that fecal samples analyzed from TAC mice that received JAX fecal material gradually separated from samples obtained from sham-and TAC feces–inoculated TAC mice over time (P = 0.001 and P = 0.003, respectively, ANOSIM multivariate data analysis) and became similar to samples obtained from sham- and JAX feces–inoculated JAX mice (Fig. 3A). In contrast, TAC-inoculated TAC mice did not change in community diversity relative to sham-inoculated TAC mice (P = 0.4, ANOSIM). Reciprocal transfer of TAC fecal material into JAX hosts resulted in a statistically significant change in community diversity (P = 0.003, ANOSIM), yet the distance of the microbial shift was smaller (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3. Direct administration of Bifidobacterium to TAC recipients with established tumors improves tumor-specific immunity and response to αPD-L1 mAb therapy.

(A) Principal coordinate analysis plot of bacterial β-diversity over time in groups treated as in Fig. 2A, each group is made up of at least two cages, three or four mice per cage; data represent three independent experiments; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (ANOSIM). (B) Phylogenetic analysis of taxa that are of significantly different abundance in newly arrived JAX versus TAC mice FDR < 0.05 (non-parametric t test); bars represent log-transformed fold changes, inner circle, log10(10); middle circle, log10(100); outer circle, log10(1000). (C) Heat map showing relative abundance over time of significantly altered genus-level taxa in JAX-fed TAC mice FDR < 0.05 (nonparametric t test); columns depict individual mice; each time point shows mice from two separate cages, three or four mice per cage. (D) Correlation plot of relative abundance of Bifidobacterium OTU_681370 in fecal material obtained from groups, as in (A), 14 days after arrival and frequency of SIY+ CD8+ T cells in tumor; P = 1.4 × 10−5, FDR = 0.0002, correlation R2 = 0.86 (univariate regression). (E) B16.SIY tumor growth kinetics in TAC mice, untreated or treated with Bifidobacterium 7 and 14 days after tumor implantation, αPD-L1 mAb 7, 10, 13, and 16 days after tumor implantation, or both regimens. (F) IFN-γ ELISPOT assessed 5 days after start of treatment. (G) Percentage of tumor-infiltrating SIY+ CD8+ Tcells, determined by flow cytometry 14 days after start of treatment. Means ± SEM analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction (E) or individual mice with means ± SEM analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak correction (F) and (G), and are combined from two independent experiments; five mice per group per experiment: *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Comparative analysis showed that 257 taxa were of significantly different relative abundance in JAX mice relative to TAC mice [false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05, nonparametric t test] (Fig. 3B and table S1). Members belonging to several of these groups were similarly altered in JAX-fed TAC mice relative to sham- or TAC-inoculated TAC mice (Fig. 3C and tables S1 and S2). To further identify functionally relevant bacterial taxa, we asked which genus-level taxa were significantly associated with accumulation of activated antigen-specific T cells within the tumor microenvironment across all permutations (Fig. 2C). The only significant association was Bifidobacterium (P = 5.7 × 10−5, FDR = 0.0019, univariate regression) (table S3), which showed a positive association with antitumor T cell responses and increased in relative abundance over 400-fold in JAX-fed TAC mice (Fig. 3C). Stimulatory interactions between bifidobacteria and the host immune system, including those associated with interferon-γ (IFN-γ), have been described previously (13–16). We thus hypothesized that members of this genus could represent a major component of the beneficial antitumor immune effects observed in JAX mice.

At the sequence level, Bifidobacterium operational taxonomic unit OTU_681370 showed the largest increase in relative abundance in JAX-fed TAC mice (table S1) and the strongest association with antitumor T cell responses across all permutations (Fig. 3D and table S3). We further identified this bacterium as most similar to B. breve, B. longum, and B. adolescentis (99% identity). To test whether Bifidobacterium spp. may be sufficient to augment protective immunity against tumors, we obtained a commercially available cocktail of Bifidobacterium species, which included B. breve and B. longum and administered this by oral gavage, alone or in combination with αPD-L1, to TAC recipients bearing established tumors. Analysis of fecal bacterial content revealed that the most significant change in response to Bifidobacterium inoculation occurred in the Bifidobacterium genus (P = 0.0009, FDR = 0.015, nonparametric t test), with a 120-fold increase in OTU_681370 (fig. S2A and table S4), which suggested that the commercial inoculum contained bacteria that were at least 97% identical to the taxon identified in JAX and JAX-fed TAC mice. An increase in Bifidobacterium could also be detected by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (fig. S2B).

Bifidobacterium-treated mice displayed significantly improved tumor control in comparison with their non-Bifidobacterium treated counterparts (Fig. 3E), which was accompanied by robust induction of tumor-specific T cells in the periphery (Fig. 3F) and increased accumulation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells within the tumor (Fig. 3G and fig. S2C). These effects lasted several weeks (fig. S2, D and E).

The therapeutic effect of Bifidobacterium feeding was abrogated in CD8-depleted mice (fig. S3A), which indicated that the mechanism was not direct but rather through host antitumor T cell responses. Heat inactivation of the bacteria before oral administration also abrogated the therapeutic effect on tumor growth and reduced tumor-specific T cell responses to baseline (fig. S3, B to D), which suggested that the antitumor effect requires live bacteria. As an alternative strategy, we tested the therapeutic effect of B. breve and B. longum strains obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, which also showed significantly improved tumor control (fig. S4A). Administration of Bifidobacterium to TAC mice inoculated with B16 parental tumor cells or MB49 bladder cancer cells also resulted in delayed tumor outgrowth (fig. S4, B and C, respectively). Oral administration of Lactobacillus murinus to TAC mice, which was not among the overrepresented taxa in JAX-fed mice, had no effect on tumor growth (fig. S4D) or on tumor-specific T cell responses (fig. S4E), which suggested that modulation of antitumor immunity depends on the specific bacteria administered. Collectively, these data point to Bifidobacterium as a positive regulator of anti-tumor immunity in vivo.

Upon inoculation with Bifidobacterium, a small set of species were altered in parallel with Bifidobacterium (ANOSIM, P = 0.003) (fig. S5A and table S4), however, for the most part, they did not resemble the changes observed with JAX feces administration. Although we observed reductions (~2- to 10-fold) in members of the order Clostridiales, as well as in butyrate-producing species, upon Bifidobacterium inoculation, which could point to an inhibitory effect on the regulatory T cell compartment (17–19), we did not observe any difference in the frequency of CD4+ Foxp3+ T cells in tumors isolated from JAX and TAC mice (fig. S5B). Thus, although we cannot definitively rule out an indirect effect, it is unlikely that Bifidobacterium is acting primarily through modulation of the abundance of other bacteria.

We next assessed whether translocation of Bifidobacterium was occurring into the mesenteric lymph nodes, spleen, or tumor; however, no Bifidobacterium was detected in any of the organs isolated from Bifidobacterium-gavaged tumor-bearing mice (fig. S5C). We thus concluded that the observed systemic immunological effects are likely occurring independently of bacterial translocation.

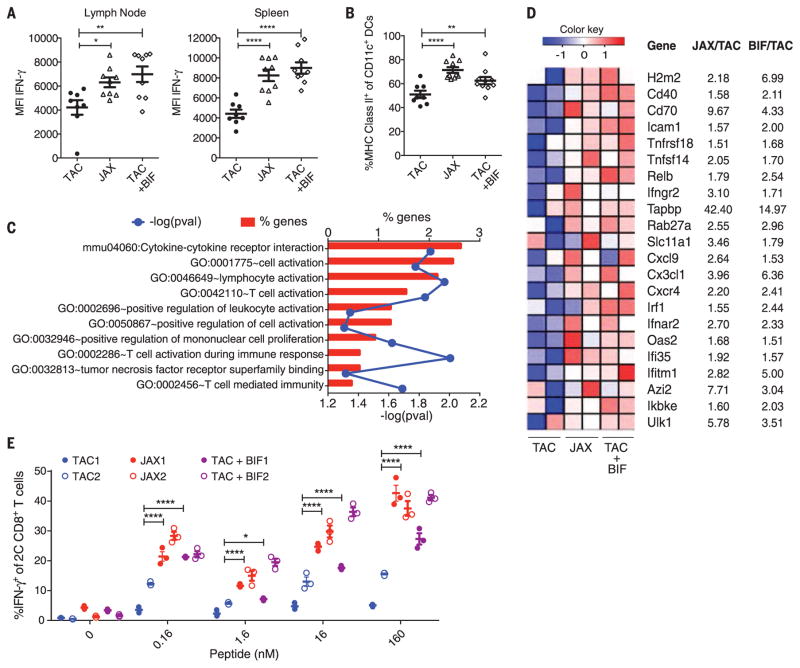

We subsequently interrogated the immunologic mechanisms underlying the observed differences in T cell responses between TAC, JAX, and Bifidobacterium-treated TAC mice (fig. S6A). CD8+ SIY-specific 2C T cell receptor (TCR) Tg T cells exposed to tumors in JAX and Bifidobacterium-treated TAC mice exhibited greater expansion in the tumor-draining lymph node, as compared with their counterparts in TAC mice (fig. S6B). However, they produced markedly greater IFN-γ in both the tumor-draining lymph node and the spleen of JAX and Bifidobacterium-fed TAC tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 4A), consistent with our analyses of the endogenous T cell response (Figs. 1C, 2E, and 3F). These data pointed to an improvement in immune responses upstream of T cells, at the level of host dendritic cells (DCs). Consistent with this hypothesis, we found an increased percentage of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) Class IIhi DCs in the tumors of JAX and Bifidobacterium-treated TAC mice (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. Dendritic cells isolated from JAX and Bifidobacterium-fed TAC mice show increased expression of genes associated with antitumor immunity and heightened capability for Tcell activation.

(A) Quantification of IFN-γ mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 2C CD8+ Tcells in the tumor-draining lymph node (left) and spleen (right) of TAC, JAX, and Bifidobacterium-fed TAC mice on day 7 after adoptive transfer. (B) Percentage of MHC Class IIhi DCs in tumors isolated from TAC, JAX, and Bifidobacterium-fed TAC mice 40 hours after tumor implantation as assessed by flow cytometry. Data in (A) and (B) show individual mice with means ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak correction; representative of two to four independent experiments, eight or nine mice per group per experiment: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001. (C) Enriched biological pathways and functions found within the subset of elevated genes in JAX and Bifidobacterium-treated TAC-derived DCs relative to untreated TAC DCs isolated from tumors 40 hours after tumor inoculation, as assessed by DAVID pathway analysis. Red bars indicate the percentage of genes in a pathway up-regulated in DCs isolated from JAX and Bifidobacterium-fed TAC mice. Blue line indicates P values calculated by Fisher’s exact test. (D) Heat map of key antitumor immunity genes in DCs isolated from JAX, Bifidobacterium-treated TAC or untreated TAC mice. Mean fold-change for each gene transcript is shown on the right. (E) Quantification of IFN-γ+ 2C TCR Tg CD8+ Tcells stimulated in vitro with DCs purified from peripheral lymphoid tissues of naïve TAC, JAX, and Bifidobacterium-treated TAC mice in the presence of different concentrations of SIY peptide. Analyses in (C) to (E) were performed on data combined from two independent experiments, five mice pooled per group per experiment. (E) Technical replicates of pooled samples from each experiment separately and were analyzed by fitting a linear mixed model, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons: *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001.

We therefore used genome-wide transcriptional profiling of early tumor-infiltrating DCs isolated from TAC, JAX, and Bifidobacterium-treated TAC mice (fig. S7A and table S5). Pathway analysis of 760 gene transcripts up-regulated in both JAX and Bifidobacterium-treated TAC-derived DCs relative to DCs from untreated TAC mice identified cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, T cell activation, and positive regulation of mononu-clear cell proliferation as significantly enriched pathways (Fig. 4C and fig. S7B). Many of these genes have been shown to be critical for antitu-mor responses, including those involved in CD8+ T cell activation and costimulation [H2-m2 (MHC-I), Cd40, Cd70, and Icam1] (20–22); DC maturation (Relb and Ifngr2) (23, 24); antigen processing and cross presentation (Tapbp, Rab27a, and Slc11a1) (25–27); chemokine-mediated recruitment of immune cells to the tumor microenvironment (Cxcl9, Cx3cl1, and Cxcr4) (28–30); and type I interferon signaling (Irf1, Ifnar2, Oas2, Ifi35, and Ifitm1) (31, 32) (Fig. 4D and fig. S7C). Expression of these genes was also increased in murine bone marrow–derived DCs stimulated with Bifidobacterium in vitro (table S6), consistent with previous reports that these species of Bifidobacterium can directly elicit DC maturation and cytokine production (13).

To test whether functional differences in DCs isolated from TAC, JAX, and Bifidobacterium-treated TAC mice could be sufficient to explain the differences in T cell priming observed in vivo, we purified DCs from lymphoid tissues of naïve TAC, JAX, and Bifidobacterium-treated TAC mice and tested their ability to induce carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)–labeled CD8+ SIY-specific 2C TCR Tg T cell proliferation and acquisition of IFN-γ production in vitro. DCs purified from JAX and Bifidobacterium-treated TAC mice induced 2C T cell proliferation at lower antigen concentration than did DCs purified from naïve TAC mice (fig. S8, A and B). Furthermore, at all antigen concentrations, JAX-derived DCs elicited elevated levels of T cell IFN-γ production (Fig. 4E and fig. S8A). We observed similar effects upon oral administration of Bifidobacterium to TAC mice before DC isolation (Fig. 4E and fig. S8A). Taken together, these data suggest that commensal Bifidobacterium-derived signals modulate the activation of DCs in the steady state, which in turn supports improved effector function of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells.

Our studies demonstrate an unexpected role for commensal Bifidobacterium in enhancing anti-tumor immunity in vivo. Given that beneficial effects are observed in multiple tumor settings and that alteration of innate immune function is observed, this improved antitumor immunity could be occurring in an antigen-independent fashion. The necessity for live bacteria may imply that Bifidobacterium colonizes a specific compartment within the gut that enables it to interact with host cells that are critical for modulating DC function or to release soluble factors that disseminate systemically and lead to improved DC function.

Our results do not rule out a contribution of other commensal bacteria species in having the capability to regulate antitumor immunity, either positively or negatively. Our data support the idea that one source of intersubject heterogeneity with regard to spontaneous antitumor immunity and therapeutic effects of antibodies targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis may be the composition of gut microbes, which could be manipulated for therapeutic benefit. These principles could apply to other immunotherapies, such as antibodies targeting the CTLA-4 pathway. Similar analyses can be performed in humans, by using 16S rRNA sequencing of stool samples from patients receiving checkpoint blockade or other immunotherapies, to identify commensals associated with clinical benefit.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

R code for gene expression analyses can be found at https://github.com/kipkeston/TG_Microbiota; microarray data can be found at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE73475 and www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE73476; 16S rRNA sequencing data can be found at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/297465. The data reported in this manuscript are presented in the main paper and in the supplementary materials. We thank D. Ringus for anaerobic culture of bifidobacteria and colony quantification, Y. Zhang for providing Lactobacillus murinus cultures, and R. Sweis for providing the MB49 bladder cancer cell line. This work was supported by a Team Science Award from the Melanoma Research Alliance, and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH, P30 Digestive Disease Research Core Center Grant (DK42086), the University of Chicago Cancer Biology training program (5T32CA009594-25), and the Cancer Research Institute fellowship program. The University of Chicago has filed a patent application that relates to microbial community manipulation in cancer therapy.

Footnotes

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Hodi FS, et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamid O, et al. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:134–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tumeh PC, et al. Nature. 2014;515:568–571. doi: 10.1038/nature13954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spranger S, et al. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:200ra116. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ji RR, et al. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61:1019–1031. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1172-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gajewski TF, Louahed J, Brichard VG. Cancer J. 2010;16:399–403. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181eacbd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Science. 2012;336:1268–1273. doi: 10.1126/science.1223490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ivanov II, II, Honda K. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:496–508. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAleer JP, Kolls JK. Immunity. 2012;37:10–12. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iida N, et al. Science. 2013;342:967–970. doi: 10.1126/science.1240527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viaud S, et al. Science. 2013;342:971–976. doi: 10.1126/science.1240537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivanov II, II, et al. Cell. 2009;139:485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.López P, Gueimonde M, Margolles A, Suárez A. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010;138:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ménard O, Butel MJ, Gaboriau-Routhiau V, Waligora-Dupriet AJ. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:660–666. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01261-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong P, Yang Y, Wang WP. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawahara T, et al. Microbiol Immunol. 2015;59:1–12. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arpaia N, et al. Nature. 2013;504:451–455. doi: 10.1038/nature12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith PM, et al. Science. 2013;341:569–573. doi: 10.1126/science.1241165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atarashi K, et al. Science. 2011;331:337–341. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackey MF, et al. J Immunol. 1998;161:2094–2098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scholer A, Hugues S, Boissonnas A, Fetler L, Amigorena S. Immunity. 2008;28:258–270. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bak SP, et al. J Immunol. 2012;189:1708–1716. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan J, et al. Immunol Lett. 2004;94:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pettit AR, et al. J Immunol. 1997;159:3681–3691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Compeer EB, Flinsenberg TWH, van der Grein SG, Boes M. Front Immunol. 2012;3:37. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jancic C, et al. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:367–378. doi: 10.1038/ncb1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stober CB, Brode S, White JK, Popoff JF, Blackwell JM. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5059–5067. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00153-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kabashima K, et al. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1249–1257. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nukiwa M, et al. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:1019–1027. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang L, et al. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:203–213. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuertes MB, et al. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2005–2016. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woo SR, et al. Immunity. 2014;41:830–842. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.