CONSPECTUS

A large class of heme and nonheme metalloenzymes utilize O2 or its derivatives (e.g. H2O2) to generate high-valent metal-oxo intermediates for performing challenging and selective oxidations. Due to their reactive nature, these intermediates are often short-lived and very difficult to characterize. Synthetic chemists have sought to prepare analogous metal-oxo complexes with ligands that impart enough stability to allow for their characterization and an examination of their inherent reactivity. The challenge in designing these molecules is to achieve a balance between their stability, which should allow for their in situ characterization or isolation, and their reactivity, in which they can still participate in interesting chemical transformations. This review focuses on our recent efforts to generate and stabilize high-valent manganese-oxo porphyrinoid complexes, and tune their reactivity in the oxidation of organic substrates.

Dioxygen can be used to generate a high-valent MnV(O) corrolazine (MnVO(TBP8Cz)) by irradiation of MnIII(TBP8Cz) with visible light in the presence of a C–H substrate. Quantitative formation of the MnV(O) complex occurs with concomitant selective hydroxylation of the benzylic substrate hexamethylbenzene. Addition of a strong H+ donor converted this light/O2/substrate reaction from a stoichiometric to a catalytic process with modest turnovers. The addition of H+ likely activates a transient MnV(O) complex to achieve turnover, whereas in the absence of H+, the MnV(O) complex was an unreactive, “dead-end” complex. Addition of anionic donors to the MnV(O) complex also leads to enhanced reactivity, with a large increase in the rate of 2-electron oxygen-atom-transfer (OAT) to thioether substrates. Spectroscopic characterization (Mn K-edge X-ray absorption and resonance Raman spectroscopies) revealed that the anionic donors (X−) bind to the MnV ion to form six-coordinate [MnV(O)(X)]− complexes. An unusual “V-shaped” Hammett plot for the oxidation of para-substituted thioanisole derivatives suggested that six-coordinate [MnV(O)(X)]− complexes can act as both electrophiles or nucleophiles, depending on the nature of the substrate. Oxidation of the MnV(O) corrolazine resulted in the in situ generation of an MnV(O) π-radical cation complex, [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz•+)]+, which exhibited more than a 100-fold rate increase in the oxidation of thioethers. The addition of Lewis acids (LA: ZnII, B(C6F5)3) to the closed-shell, diamagnetic MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) stabilized a paramagnetic valence tautomer MnIV(O)(TBP8Cz•+):LA, which was characterized as a second π-radical cation complex by NMR, EPR, UV-vis, and high resolution CSI-MS. The MnIV(O)(TBP8Cz•+):LA complexes are able to abstract H• from phenols and exhibit a rate enhancement of up to ∼100-fold over the parent MnV(O) valence tautomer. In contrast, a large decrease in rate is observed for OAT for the MnIV(O)(TBP8Cz•+):LA complexes. The rate enhancement for HAT may derive from the higher redox potential for the π-radical cation complex, while the large rate decrease seen for OAT may come from a decrease in electrophilicity for an MnIV(O) versus MnV(O) complex.

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

High-valent metal-oxo species play important roles in the functioning of both heme and non-heme metalloenzymes. An iron(IV)-oxo porphyrin π-radical cation is the intermediate that carries out the oxidation reactions for heme enzymes including Cytochrome P450, peroxidase, and catalase.1–3 This species, labeled Compound I (Cpd-I) in the heme literature, is capable of performing a range of selective and challenging oxidations, from the hydroxylation of strong C– H bonds, to the epoxidation of alkenes, to the sulfoxidation of thioether substrates.2–4 Non-heme iron enzymes rely on a similar ferryl intermediate, although the overall oxidation state (FeIV(O)) is lower by one unit because there is no porphyrin ring available for storing an extra positive charge.5 Manganese porphyrins have been examined as surrogates for iron hemes in heme proteins including P4506,7 and myoglobin.8,9 Additionally, interest in Mn-oxo chemistry has seen a large resurgence because of the possible roles of Mn(O) species in water oxidation carried out by Photosystem II.10,11

Synthetic chemists have put much effort into the synthesis and study of high-valent metal-oxo complexes with two main objectives: 1) to determine the spectroscopic signatures and fundamental reactivity patterns of these species so this information can be compared to the biological systems and used to define plausible enzymatic mechanistic scenarios and 2) to construct bioinspired oxidation catalysts that take advantage of the reactivity/selectivity properties of M(O) species. The obvious challenge to studying high-valent Fe(O) and Mn(O) complexes of biological relevance is the lack of stability of these species. The goal for the synthetic chemist has been to devise ligands which can provide enough stability to M(O) species to allow for their spectroscopic characterization and/or isolation, and also allow for rational modification of the ligand environment to assess structure/function relationships.

Metalloenzymes such as P450 are capable of generating high-valent M(O) species from dioxygen. In contrast, synthetic methods typically require high-energy oxidants (e.g. iodosylbenzene) to prepare M(O) species that can be spectroscopically characterized or isolated. An ongoing challenge is thus to utilize O2 to prepare identifiable, yet reactive metal-oxo complexes that can oxidize organic substrates.

The contraction of the porphyrin core has led to the development of corroles and corrolazines, and these porphyrinoid compounds have enjoyed significant success in stabilizing high-valent metal-oxo and related (e.g. metal-imide, metal-nitride) species.12,13 Our laboratory has focused on the synthesis and reactivity of the corrolazine (Cz) scaffold, which has provided access to high-valent Fe-oxo, Mn-oxo, Mn-imido complexes, as well as other (Co, Cu, V) high oxidation state complexes.14,15 The advantages in stability of M(O) complexes brought about by the Cz scaffold have allowed us to test fundamental structure/function paradigms, including those that involve axial ligand effects and the influence of the redox-active ability of the porphyrinoid framework. We have also discovered a method for utilizing O2 to prepare a high-valent Mn-oxo complex, and to perform catalytic oxidations under certain conditions. In this review we will describe our recent results on high-valent manganese-oxo corrolazines.

2. MnIII(TBP8Cz) and MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)

Our group reported the first synthesis of corrolazine in 2001. The starting material is a tetraazaporphyrin (or porphyrazine), which can be prepared from available nitrile derivatives. The porphyrin is ring-contracted by treatment with PBr3 to give a phosphorous corrolazine with a PV(O), PV(OH), or PV(OR)2 group in the internal cavity. A difficult step is removal of phosphorus to give metal-free Cz, which requires Na/NH3(l) reduction at –78 °C. Details of the synthesis were reviewed previously.14,15 The structural relationships between the different porphyrinoid members can be seen in Figure 1. The core size of the corrolazine (Npyrrole-Npyrrole(trans) = 3.54 Å) is the smallest of the porphyrinoid ligands depicted, and when fully deprotonated, the corrolazine is trianionic with an 18 π-electron aromatic core.16,17

Figure 1.

Core structures of porphyrinoid ligands.

The manganese corrolazine, MnIII(TBP8Cz) (TBP8Cz = octakis(p-tert-butylphenyl)corrolazinato3−) is easily prepared by addition of Mn(acac)3 to metal-free TBP8CzH3. X-ray diffraction studies of MnIII(TBP8Cz) have revealed two different axial ligands bound to the Mn ion, MeOH or H2O, depending on crystallization conditions.18,19 Hydrogen bonds are evident between these axial donors and nearby meso-N atoms in the crystal lattice. The high-valent metal oxo complex, MnV(O)(TBP8Cz), was first prepared from the oxidation of MnIII(TBP8Cz) by iodosylbenzene in CH2Cl2. We designed the corrolazine ligand to stabilize high-valent states, and the MnV(O) complex was not only stable in solution under ambient conditions, but was also amenable to purification by chromatography and isolation as a solid. As seen in Figure 2, the MnIII and MnV(O) complexes have formed the basis of a wide range of derivatives obtained from the addition of axial ligands, protons, oxidants and Lewis acids. These species are easily distinguishable by their spectroscopic features, and exhibit novel and varied patterns of reactivity. This review discusses these findings.

Figure 2.

Transformations of manganese corrolazines. (Ar = p-tert-butylphenyl)

3. OXYGEN ACTIVATION

A long-standing goal in model complex chemistry and in the pursuit of oxidation catalysts has been to generate high-valent metal-oxo species from dioxygen. It was shown that diiron µ-oxo porphyrins derived from O2 are susceptible to photocleavage to generate postulated FeIV(O)(porph) intermediates involved in catalytic oxidations.20 Chromium(III) corroles react with O2 to give CrV(O) complexes and catalytically oxidize PPh3.21 There are still few Fe or Mn complexes that can activate O2 in the absence of co-reductants to give M(O) species and oxidize organic substrates. During our work with Mn corrolazines, we observed that aerobic solutions of MnIII(TBP8Cz) would, on occasion, slowly convert to the bright green typical of MnV(O)(TBP8Cz). This transformation was difficult to reproduce, but careful examination of reaction conditions led to the finding that aerobic solutions of MnIII(TBP8Cz) required irradiation by visible light (>400 nm) to produce MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) (Scheme 1).22 This reaction was also dependent on the nature of the solvent. Confirmation that O2 was the source of the terminal oxo ligand was obtained by isotope labeling with 18O2. In contrast, addition of H218O did not give any labeled product, ruling out H2O as an oxygen source. The participation of singlet O2 was ruled out by the use of a 1O2 trap.22

Scheme 1.

Production of MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) from MnIII(TBP8Cz), O2, and Visible Light. Adapted from refs 22, 24. Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.

From kinetic data in cyclohexane we speculated that the mechanism of O2 activation involved autoxidation of the solvent.22 A proposed mechanism involved a photochemically activated MnIII complex reacting with O2 to form an MnIV-superoxo species, which then abstracts an H atom from solvent to generate solvent radicals that can then propagate in a solvent-assisted autoxidation. The MnV(O) complex could arise from homolytic cleavage of MnIV(OOH), or other pathways.

The solvent dependence of the formation of the MnV(O) complex suggested to us that running the reaction in an inert solvent might allow us to control the oxidation of exogenous C–H substrates. We tested the inert solvent benzonitrile (benzene: BDFE (C-H gas phase) = 104.7 kcal mol−1)23 in the light-driven aerobic oxidation of MnIII(TBP8Cz), and no reaction was observed.24 However, the addition of a series of toluene derivatives [Ph(CH3)n; n = 1 – 6] to the PhCN reaction as proton/electron sources led to production of MnV(O)(TBP8Cz). Analysis of the reaction mixture, with hexamethylbenzene (HMB) (BDFE (C–H) = 83.2 kcal mol−1)23 as substrate, revealed the major product was pentamethylbenzyl alcohol (87% yield) with a minor amount of pentamethylbenzaldehyde (8% yield) (Scheme 1). The rate of this reaction increased with an increase in the number of methyl groups on the substrate, where toluene showed the slowest rate (4.0 × 10−7 M−1 s−1) and hexamethylbenzene showed the fastest rate (8.0 × 10−5 M−1 s−1). A kinetic isotope effect (KIE) of 5.4 for toluene and 5.3 for mesitylene was determined. From these findings we proposed that HAT from the toluene derivatives is the rate-determining step.24

Femtosecond laser flash photolysis was employed to characterize the photochemical transformation. Upon femtosecond laser excitation (λexc = 393 nm) of MnIII(TBP8Cz), transient absorption difference spectra revealed short-lived excited states with features at 530 and 774 nm. Monitoring these bands under O2 versus N2 atmosphere showed that the 774 nm species decayed more rapidly in the presence of O2. From the transient absorption data, a mechanism was proposed involving an excited state of MnIII(TBP8Cz) reacting with O2.24

The proposed mechanism is shown in Scheme 2. Photoexcitation generates a short-lived 5T1 excited state (530 nm), which undergoes rapid intersystem crossing to the longer-lived 7T1 excited state.25 The tripseptet state is identified by the 774 nm peak and reacts with O2 to give a putative superoxo complex, MnIV(OO•−)(TBP8Cz), which can either abstract a hydrogen atom from substrate to give MnIV(OOH)(TBP8Cz) and benzyl radical, or undergo back electron-transfer (ET). Once formed, the hydroperoxo complex can produce MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) and the benzyl alcohol derivative.

Scheme 2.

Mechanism for the Photochemical Oxidation of MnIII(TBP8Cz). Adapted from ref 24. Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.

The experiments in inert PhCN showed that the oxidation of the toluene derivatives appeared to be a promising method for the aerobic oxidation of certain C-H substrates, but the final MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) complex was stable, limiting this chemistry to a stoichiometric process. Catalytic turnover was seen only with weaker C–H bond substrates (e.g. dihydroacridine, BDFE = 69 kcal/mol) or with O-atom acceptors such as PPh3.22,24,26 We hypothesized that the addition of strong H+ donors might activate MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) toward oxidation of the toluene derivatives, regenerating the starting MnIII(TBP8Cz) and yielding catalytic turnover.

Addition of the strong proton donor [H(OEt2)2]+[B(C6F5)4]− (H+[B(C6F5)4]−) to the oxidation of HMB with air, light (hv > 400 nm) and MnIII(TBP8Cz) resulted in catalytic activity (scheme 3).19 MnIII(TBP8Cz) converted to a new species with UV-vis bands at 446 and 728 nm, which slowly bleached over the course of the reaction. Control reactions showed that light, O2, and MnIII(TBP8Cz) were all required for production of oxidized products.19

Scheme 3.

Catalytic Aerobic Oxidation. Adapted from ref 19. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

Insight into the catalytically active species was obtained by examining the MnIII complex in the presence of H+. Addition of 1 equiv of H+[B(C6F5)4]− to MnIII(TBP8Cz) resulted in a spectrum (446, 730 nm) that was nearly identical to that observed for the catalytic reaction. However, addition of a second equiv of H+ gave a new species with a spectral signature of 470, 763 nm. The distinct spectra for the three MnIII species are shown in Figure 3. We were successful in crystallizing and characterizing all three of these complexes by X-ray diffraction (XRD). The neutral MnIII complex is five-coordinate with an axial water molecule. Upon protonation with 1 H+, a remote site on the corrolazine ring is protonated to give [MnIII(H2O)(TBP8Cz(H))][B(C6F5)4]. Addition of 2 H+ results in the diprotonated [MnIII(H2O)(TBP8Cz(H)2)][B(C6F5)4]2 complex, in which two of the meso-nitrogen atoms are protonated (Figure 3). Dissolution of these crystalline complexes showed UV-vis spectra that were identical to in situ preparations, providing definitive characterization for the different protonation states in Figure 3.19

Figure 3.

(top) Displacement ellipsoid plots (50% probability level) for MnIII(TBP8Cz)(H2O) (left), [MnIII(H2O)(TBP8Cz(H))]+ (center) and [MnIII(H2O)(TBP8Cz(H)2)]2+ (right) at 110(2) K. (bottom left) UV–vis spectral changes for MnIII(TBP8Cz) upon addition of 1 equiv (blue line) and 2 equiv (red line) of H+[B(C6F5)4]− in CH2Cl2. (bottom right) Addition of H+[B(C6F5)4]− to MnIII(TBP8Cz). Adapted from ref 19. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

The reaction of crystalline, monoprotonated [MnIII(H2O)(TBP8Cz(H))][B(C6F5)4] with light, O2 and HMB under catalytic conditions led to PMBOH and PBMCHO, but only in sub-stoichiometric amounts. The formation of the valence tautomer [MnIV(O)(TBP8Cz•+)(H)]+ (418, 784 nm) (vide infra) was also noted by UV-vis. In contrast, the same reaction with crystalline diprotonated [MnIII(H2O)(TBP8Cz(H)2)][B(C6F5)4]2 did give catalytic turnover. It was shown by UV-vis that the diprotonated starting material rapidly converted to the monoprotonated complex in benzene during catalysis. Independent experiments showed that exogenous H2O in C6H6 was a sufficient base to deprotonate the second meso-NH+ proton of the diprotonated MnIII complex. The resulting monoprotonated complex that forms under catalytic conditions slowly decomposed over 5 h.19

The catalytic cycle in Scheme 4 was postulated for the catalytic aerobic oxidation of HMB. With 2 equiv of H+ in C6H6 under aerobic conditions, the monoprotonated MnIII complex is the resting state of the catalyst. The monoprotonated complex exhibits similar photochemistry to the neutral complex, resulting in the generation of a tripseptet (7T1) excited state which reacts with O2 to form the proposed MnIV(O2•−) complex. The superoxo species then abstracts H• from HMB, leading to MnIV(OOH) and HMB radical, which can then recombine via O-O cleavage to give PMBOH and the MnV(O) complex. We proposed that the MnV(O) complex was activated by the excess H+ present under catalytic conditions to give further oxidation products and regenerate the MnIII resting state.19

Scheme 4.

Proposed Catalytic Cycle for the Oxidation of HMB. Reproduced from ref 19. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

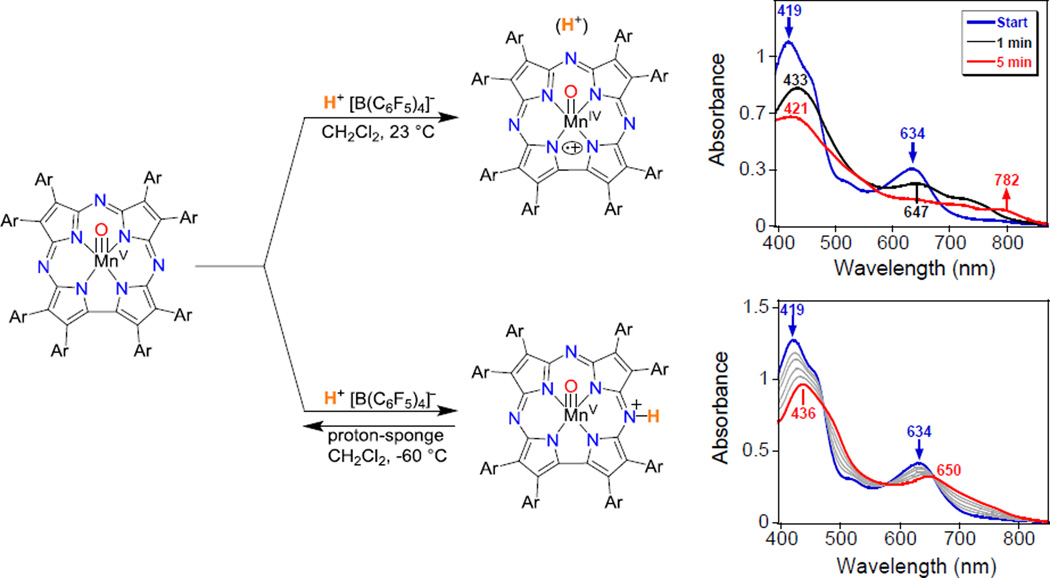

To gain more information about the activated form of the MnV(O) complex in the presence of H+, the isolated MnV(O) complex was reacted with H+[B(C6F5)4]− and monitored by UV-vis. Interestingly, the reaction with acid leads to two distinct species depending upon the temperature. As shown in Figure 4, addition of H+ at 23 °C gives the valence tautomer MnIV(O)(TBP8Cz•+):H, in which electron transfer has occurred from the Cz ring to the metal ion and suggests that protonation occurs at the terminal oxo position. In contrast, the same reaction at −60 °C resulted in a new spectrum with peaks at 436 and 650 nm, which was reversible upon addition of proton sponge. NMR analysis, including deuterium exchange and two-dimensional NOESY and COSY spectra, identified the site of protonation as one of the meso-N atoms (Figure 4), similar to what was seen for the MnIII complex (Figure 3). These experiments showed that there are two possible sites of protonation on the Mn(O) complex. The presence of two equiv of H+ under catalytic conditions may activate the Mn(O) complex through a combination of the potential proton binding sites shown in Figure 4.19

Figure 4.

Scheme showing the addition of H+ to MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) (left). UV–vis spectra of MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) + H+[B(C6F5)4]− (blue line) to give [MnIV(O)(TBP8Cz•+)(H)]+ (red line) in CH2Cl2 at 23 °C (top right). UV-vis spectral changes (0 – 1 min) for the addition of H+[B(C6F5)4]− to MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) (blue line) to give [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz(H))]+ (red line) in CH2Cl2 at –60 °C (bottom right). Adapted from ref 19. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

Our work on O2 chemistry showed for the first time that an MnV(O) complex could be synthesized from an MnIII precursor and air, visible light, and an H-atom donor. We also determined that MnIII(TBP8Cz) could function as a pre-catalyst for the light-driven, aerobic oxidation of the toluene derivative HMB in the presence of a strong proton donor.

4. INFLUENCE OF AXIAL LIGANDS ON REACTIVITY

In an early study on axial ligands, we showed that the addition of anionic donors (F−, CN−) to MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) resulted in large rate enhancements (760 – 16,000-fold) for HAT reactions with C-H substrates.15,27 It was hypothesized that coordination of these donors led to an increase in driving force for HAT and resulted in greatly enhanced reactivity. This work has been reviewed elsewhere.15 Kinetic analysis suggested a pre-equilibrium binding of the donor prior to the rate-determining step. A binding constant for F− of K = (163 ± 7) M−1 was obtained.27 Mass spectral evidence was provided for [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(X)]− (X = F−, CN−), but the instability of these species did not allow for characterization by XRD.

The six-coordinate [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− complex was characterized by X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS).28 The decrease in the pre-edge peak is consistent with converting the MnV(O) complex from 5- to 6-coordinate (Figure 5). The extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) for [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− indicated that a sixth C/N donor at 2.21 Å was present, in accord with a coordinated cyanide ligand. Interestingly, the coordination of CN− to MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) did not cause a significant lengthening of the Mn–O bond.

Figure 5.

(top) Formation of six-coordinate [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(X)]− complexes. (bottom left) Normalized Mn K-edge XAS data for MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) with none (red), 10 (dark blue) and 100 (light blue) equiv CN−. (bottom right) Resonance Raman spectra of [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(X)]− where X = no ligand (black), F− (blue), N3− (red), or OCN− (purple). Adapted from refs 28, 29. Copyright 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

Resonance Raman (RR) spectra show a strong Mn–O vibrational mode at 981 cm−1 for MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) that downshifts 5 cm−1 to 976 cm−1 when the anionic donors F−, N3−, or OCN− were present (Figure 5).29,30 All attempts to measure the RR spectra of the CN − adduct failed, due the rapid decay of the complex at higher concentrations. The assignment of the 976 cm −1 peak was confirmed by the predicted downfield shift of 40 cm −1 for the O18-labeled six-coordinate complexes with F− and N3−.29 These data are consistent with coordination of the anionic donors trans to the oxo group.

Having previously looked at the influence of axial donors on HAT reactivity,27 we sought to understand if similar effects on O-atom transfer (OAT) would be observed. Sulfoxidation was examined with the 5- and 6-coordinate MnV(O) complexes (Scheme 5). Smooth conversion of [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(X)]− to [MnIII(TBP8Cz)(X)]− (X = none, CN−, F−, OCN−, N3−, SCN−, NO3−) was observed after addition of RSR (R = Me, n-Bu). Second-order rate constants revealed large rate enhancements for several of the anionic donors, with the largest (24,000-fold) seen for CN−. 29 The trend in rate enhancement that was found, X = none ≈ SCN− ≈ NO3− < OCN− < N3− < F− ≪ CN−, was supported by DFT calculations.28 These results suggested that the stronger the binding interaction of X− to MnV(O), the larger the rate enhancement. An Eyring analysis was conducted on [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− plus dibutyl sulfide (DBS), and the activation parameters were ΔH‡ = 14 ± 0.4, ΔS‡ = −10 ± 0.8, ΔG‡ = 17 ± 0.5 (298 K).28 A comparison of the activation parameters for MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) (ΔH‡ = 16 ± 1, ΔS‡ = −20 ± 1, ΔG‡ = 22 ± 2)31 showed that addition of CN− lowered the overall barrier (ΔG‡) through both enthalpic and entropic contributions.

Scheme 5.

OAT to Thioether Substrates. Adapted from ref 29. Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

Further mechanistic information was obtained by examining the OAT reactivity of the six-coordinate [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(CN)]− and [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(F)]− complexes with a series of para-substituted thioanisole derivatives (X-p-C6H4SCH3; X = OMe, CH3, H, Br, C(O)OMe, CN, NO2). As with the alkyl sulfides, smooth conversion to MnIII products were seen by UV-vis, and good yield of sulfoxide obtained. Labeling of the terminal oxo ligand with 18O led to 71% isotopic incorporation in the sulfoxide product.28 A Hammett analysis of the thioanisole derivatives exhibited a negative slope for the electron-donating substituents, with ρ = − 1.39 for CN − and ρ = − 2.29 for F−. However, when electron-withdrawing substituents were tested, a positive linear slope was observed with ρ = 1.22 for CN − and ρ = 1.78 for F−, resulting in unusual “V-shaped” Hammett plots (Figure 6).29 A V-shaped Hammett plot strongly suggested a fundamental change in the mechanism of OAT, leading to two proposed pathways (Figure 6). Pathway A depicts the typical electrophilic mechanism, in which the high-valent MnV(O) complex is the electrophile. This pathway accounts for the part of the Hammett plot with a negative slope and is the anticipated mechanism for OAT. The change in mechanism can be rationalized by pathway B in Figure 6. In this pathway, a quinoid-type resonance form of the thioanisole derivative is invoked, which is stabilized by strong electron-withdrawing substituents. The oxo ligand functions as a weak nucleophile in this case, and is attracted to the partial positive charge on the sulfur center. This “umpolung” reactivity provides the mechanistic switch. A quinoid-type X-ray structure was observed for a phenylthiolate-nickel(II) complex, providing confidence in the proposed mechanism in pathway B.32

Figure 6.

(left) Hammett plots for [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(X)]− (X = CN− or F−) and para-X-substituted thioanisole derivatives. (right) Mechanistic pathways for electron-donating (Pathway A) and electron-withdrawing (Pathway B) para-substituted thioanisole derivatives. Adapted from ref 29. Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

The V-shaped Hammett plot in Figure 6 can be contrasted to the reactivity of the one-electron oxidized, cationic MnV(O)(TBP8Cz•+) complex (vide infra). Reaction of this complex with the same thioanisole derivatives resulted in a linear Hammett plot for all of the thioanisole derivatives, with ρ = −1.40. These data indicated that only an electrophilic mechanism (pathway A) is operative for the cationic Mn-oxo complex, and suggest that the positive charge on the metal complex removes any nucleophilic character. 29 Together these results show that the six-coordinate [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz)(X)] complexes are more reactive than the five-coordinate MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) in OAT reactions, and that the anionic, axially ligated Mn-oxo complexes can exhibit both electrophilic and nucleophilic character.29

5. INFLUENCE OF ONE-ELECTRON OXIDATION ON THE OAT REACTIVITY

Addition of the one-electron oxidants [(BrC6H4)3N•+](SbCl6−) or cerium(IV) ammonium nitrate (CAN) to MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) led to the generation of the one-electron oxidized π-radical-cation complex [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz•+)]+. This complex could not be isolated in the solid state, but was characterized spectroscopically in situ. Oxidation of MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) was accompanied by an immediate color change from bright green to orange-brown, and a new spectrum with peaks at 410 and 780 nm appeared (Figure 7). The broadened Soret band, and low-intensity, long-wavelength peak in the near-IR are characteristic of porphyrin π-radical cations, in which an electron has been removed from the aromatic π system. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy revealed a sharp singlet at g = 2.001, consistent with the Cz ring as the locus of oxidation and the metal remaining in an MnV oxidation state (Figure 7, inset). Spectral titrations together with previous spectroelectrochemical assignments18 supported the one-electron oxidation of the Cz ring.31

Figure 7.

Scheme and UV-vis spectra for the oxidation of (TBP8Cz)MnV(O) (10 µM) with increasing amounts of [(BrC6H4)3N•+](SbCl6−) (0–1.2 equiv) at 25 °C in CH2Cl2. Inset: X-band EPR spectrum of [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz•+)]+ (10 µM) at 15 K in CH2Cl2. Adapted from ref 31. Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

The MnV(O) π-radical-cation was examined for OAT reactivity. Addition of DMS to [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz•+)]+ generated from (BrC6H4)3N•+/MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) showed isosbestic conversion to a new spectrum (440, 470, 722 nm) characteristic of [MnIV(TBP8Cz)]+. The oxidation state of this complex was confirmed by EPR, revealing the spectrum of an S = 3/2 MnIV ion with well-resolved 55Mn hyperfine coupling.33 The OAT product DMSO was obtained in good yield (88%). For MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) and [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz+•)]+, second order rate constants with DMS were (2.0 ± 0.2) × 10 −3 M−1 s−1 and 0.25 ± 0.05 M−1 s−1, respectively, indicating a large rate enhancement (> 100-fold) for [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz•+)]+. An Eyring analysis gave ΔH‡ = 16 ± 1 kcal mol −1 for the neutral MnV(O) complex, but a much smaller ΔH‡ = 7 ± 0.8 kcal mol −1 for the one-electron oxidized complex. Both complexes gave negative ΔS‡ values as expected for a bimolecular OAT mechanism, but ΔS‡ was unusually large for [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz•+)]+ (−45 ± 3 cal K−1 mol −1). The origin of this large negative entropic factor was not determined, but it attenuates the effect of the enthalpic change, giving a more modest rate enhancement than might be expected.31

DFT calculations on the potential energy profiles of sulfoxidation corroborated the trends seen from kinetics. A concerted bimolecular mechanism for both the MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) and [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz•+)]+ was found by DFT, and a lower barrier of OAT was seen for the one-electron oxidized complex. An increase in electrophilicity for the [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz•+)]+ complex may lower the reaction barrier for OAT.31

5. LEWIS ACIDS AND VALENCE TAUTOMERISM

The addition of Lewis and Bronsted acids to MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) provided a new method for tuning the reactivity and electronic structure of this species. Addition of Zn(OTf)2, a redox-inactive Lewis acid, to the MnV(O) complex resulted in a UV-vis spectrum similar to that of the one-electron oxidized [MnV(O)(TBP8Cz•+)]+, a puzzling result.34 The spectral change was fully reversible with the addition of a Zn(II) chelator. Evans method NMR measurement revealed that the new species was paramagnetic, with µeff = 4.11 µB, (S = 1 (2.83 µB) and S = 2 (4.90 µB)). The data suggested that ZnII may be stabilizing an alternate electronic configuration, or “valence tautomer” of MnV(O)(TBP8Cz). We postulated that ZnII was binding to the oxo group and weakening the metal-oxo π-bonding, thereby favoring the MnIV(O)(TBP8Cz•+) valence tautomer.34

The MnIV(O)(π-radical-cation):ZnII complex exhibited electron-transfer reactivity significantly different from that seen for the MnV(O) starting material. The MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) valence tautomer is reduced by decamethylferrocene (Cp*2Fe, E°red = −0.59 V vs. Fc+/Fc), but not by the weaker reductant ferrocene (Fc, E°red = 0.00 V vs. Fc+/Fc). However, MnIV(O)(π-radical-cation):ZnII is easily reduced by Fc and gives an MnIV(Cz0) product. Reduction of the MnV(O) complex by Cp*2Fe leads to an MnIII product. These data indicated that the MnIV(O)(TBP8Cz+•):ZnII complex was a more powerful oxidant than the MnV(O) complex, but leads only to the one-electron reduced MnIV state. Reaction of MnIV(O)(TBP8Cz+•):ZnII with hydrogen atom donors (e.g. substituted phenols) yielded similar results.34

A nonmetallic Lewis acid, B(C6F5)3, exhibited similar chemistry to ZnII, with UV-vis and Evans method confirming the stabilization of the valence tautomer MnIV(O)(TBP8Cz•+):B(C6F5)3).35 Spectral titrations for both Lewis acids revealed similar association constants for one-to-one binding, with Ka = 2.0 × 107 M−1 for B(C6F5)3 and Ka = 4.0 × 106 M−1 for ZnII. Low-temperature, high-resolution electrospray mass spectrometry data on MnIV(O)(TBP8Cz•+):B(C6F5)3 showed the formation of a 1:1 adduct. For both ZnII and B(C6F5)3, the data are most consistent with coordination of the Lewis acid at the terminal oxo ligand, however conclusive structural characterization for these species has not yet been obtained.

The influence of B(C6F5)3 on HAT by MnIV(O)(TBP8Cz’+):B(C6F5)3 was greater than that of ZnII, with an ∼100-fold increase in HAT rate with phenols (Scheme 6). A kinetic isotope effect of kH/kD = 3.2 ± 0.3 was measured for 2,4,6-TTBP, pointing to an HAT mechanism. The trend in reactivity is shown in Scheme 6, where the MnIV(O)(TBP8Cz’+):ZnII tautomer shows a moderate rate enhancement, and MnIV(O)(TBP8Cz•+):B(C6F5)3 shows rate enhancements up to ∼100-fold relative to MnV(O). Thus the HAT reactivity of MnIV(O)(TBP8Cz•+):LA increases with the increasing strength of the Lewis acid.35

Scheme 6.

Summary of HAT reactivity of MnIV(O)(TBP8Cz•+) with substituted phenols. Adapted from ref 35. Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

In earlier work we found that the low spin MnV(O) tautomer reacts rapidly with triphenylphosphine (PPh3), an O-atom accepting reagent, and we decided that triarylphosphines were good test substrates to compare the two-electron O-atom transfer reactivity of MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) with the MnIV(O)(π-radical cation) valence tautomer. Stopped-flow UV-vis spectroscopy was required for these fast reactions, and we obtained second-order rate constants ranging from 16 ± 1 to 1.43 ± 6 × 104 M−1 s−1 for a series of substituted triarylphosphine derivatives reacting with MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) (Figure 8).36 Variation of the para substituents of the phosphine derivatives led to a linear Hammett correlation with a negative slope (ρ = − 0.91 ± 0.05), consistent with the expected mechanism where the MnV(O) complex is an electrophilic oxidant.

Figure 8.

Reaction of MnV(O)(TBP8Cz) with a series of para-substituented phosphines. Adapted from ref 36. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

There was also a strong dependence on the steric encumbrance of the PAr3 derivatives, consistent with concerted nucleophilic attack of the PAr3 substrate.

The reaction of PPh3 with the paramagnetic MnIV(O)(TBP8Cz•+):LA species (LA = ZnII, B(C6F5)3, H+) led to a dramatic decrease in the rate of OAT, with a ratio of second-order rate constants = knone/kMn(O)LA = 14,000 – 71,000. This rate inhibition strongly contrasts the increase in rate constants we observed for HAT with the π-radical cation valence tautomer. We suggested that perhaps it is the inherent electrophilicity of an MnIV(O) versus an MnV(O) unit that may be responsible for the inhibition, since the local oxidation state of +4 may lower the electrophilicity of the terminal oxo ligand compared to a local oxidation state of +5.36 The lower electrophilicity could influence the two-electron phosphine oxidation reactions as proposed, and would be exerting a different influence than the increase in redox potential seen for the π-radical cation complex, which results in faster one-electron HAT. A summary of the reactivity for the two valence tautomers is shown in Scheme 7.

Scheme 7.

Reactivity of Mn(O)(Cz) Valence Tautomers. Adapted from ref 36. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

6. Summary

The formation of a stable high-valent manganese(V)-oxo corrolazine has led to a wide variety of discoveries pertaining to the reactivity of metal-oxo complexes. It was shown that reacting manganese(III) corrolazine with light, air and a C–H substrate allowed for clean formation of the MnV(O) complex, and addition of acid to the reaction mixture allowed for catalytic turnover. The addition of anionic donors, protons, oxidants or Lewis acids to the MnV(O) corrolazine each affected the reactivity of the high-valent species in different ways. These new mechanistic insights contribute to our understanding of how the reactivity of high-valent metal-oxo intermediates is controlled in enzymatic systems. The knowledge gained from these studies also may suggest strategies for designing potential new synthetic oxidation catalysts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (GM101153) and NSF (CHE121386) to D.P.G. We would like to thank A. Confer for assistance with the TOC figure. R.A.B. is grateful for the E2SHI and Greer Fellowships.

Biographies

Heather Neu received her B.S. degree in Chemistry from the University of Wisconsin Superior in 2007, where she conducted independent undergraduate research through the McNair Scholars program under the direction of Professor Troy S. Bergstedt. In 2010, she earned her M.S. from the University of Minnesota Duluth, with Professor Victor N. Nemykin. She is currently a Ph.D. candidate at Johns Hopkins University working with Professor David P. Goldberg.

Regina Baglia received her B.S. degree in Biochemistry from Temple University in 2011, where she conducted undergraduate research through the Diamond Research Scholars program under the direction of Professor Michael J. Zdilla. She is currently a Ph.D. candidate at Johns Hopkins University working with Professor David P. Goldberg.

David Goldberg received his B.A. degree from Williams College (1989) and a Ph.D. degree from M.I.T (1995). After completing a postdoctoral fellowship at Northwestern University, he moved to Johns Hopkins University in 1998, where he is currently a Professor of Chemistry.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jung C. The mystery of cytochrome P450 Compound I A mini-review dedicated to Klaus Ruckpaul. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics. 2011;1814:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poulos TL. Heme Enzyme Structure and Function. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:3919–3962. doi: 10.1021/cr400415k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rittle J, Green MT. Cytochrome P450 Compound I: Capture, Characterization, and C-H Bond Activation Kinetics. Science. 2010;330:933–937. doi: 10.1126/science.1193478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ortiz de Montellano PR, De Voss JJ. Oxidizing species in the mechanism of cytochrome P450. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2002;19:477–493. doi: 10.1039/b101297p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ray K, Pfaff FF, Wang B, Nam W. Status of Reactive Non-Heme Metal-Oxygen Intermediates in Chemical and Enzymatic Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:13942–13958. doi: 10.1021/ja507807v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gelb MH, Toscano WA, Sligar SG. Chemical Mechanisms for Cytochrome-P-450 Oxidation - Spectral and Catalytic Properties of a Manganese-Substituted Protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1982;79:5758–5762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.19.5758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makris TM, von Koenig K, Schlichting I, Sligar SG. The status of high-valent metal oxo complexes in the P450 cytochromes. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006;100:507–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oohora K, Kihira Y, Mizohata E, Inoue T, Hayashi T. C(sp(3))-H Bond Hydroxylation Catalyzed by Myoglobin Reconstituted with Manganese Porphycene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:17282–17285. doi: 10.1021/ja409404k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zahran ZN, Chooback L, Copeland DM, West AH, Richter-Addo GB. Crystal structures of manganese- and cobalt-substituted myoglobin in complex with NO and nitrite reveal unusual ligand conformations. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2008;102:216–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Umena Y, Kawakami K, Shen JR, Kamiya N. Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9 angstrom. Nature. 2011;473:55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature09913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yano J, Yachandra V. Mn4Ca Cluster in Photosynthesis: Where and How Water is Oxidized to Dioxygen. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:4175–4205. doi: 10.1021/cr4004874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leeladee P, Jameson GNL, Siegler MA, Kumar D, de Visser SP, Goldberg DP. Generation of a High-Valent Iron Imido Corrolazine Complex and NR Group Transfer Reactivity. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:4668–4682. doi: 10.1021/ic400280x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu HY, Mahmood MHR, Qiu SX, Chang CK. Recent developments in manganese corrole chemistry. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013;257:1306–1333. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg DP. Corrolazines: New frontiers in high-valent metalloporphyrinoid stability and reactivity. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:626–634. doi: 10.1021/ar700039y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGown AJ, Badiei YM, Leeladee P, Prokop KA, DeBeer S, Goldberg DP. Synthesis and Reactivity of High-Valent Transition Metal Corroles and Corrolazines. In: Handbook of Porphyrin Science. Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. Vol. 14. Singapore: World Scientific Press; 2011. pp. 525–599. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerber WD, Goldberg DP. High-valent transition metal corrolazines. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006;100:838–857. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramdhanie B, Stern CL, Goldberg DP. Synthesis of the first corrolazine: A new member of the porphyrinoid family. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:9447–9448. doi: 10.1021/ja011229x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lansky DE, Mandimutsira B, Ramdhanie B, Clausen M, Penner-Hahn J, Zvyagin SA, Telser J, Krzystek J, Zhan R, Ou Z, Kadish KM, Zakharov L, Rheingold AL, Goldberg DP. Synthesis, characterization, and physicochemical properties of manganese(III) and manganese(V)-oxo corrolazines. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:4485–4498. doi: 10.1021/ic0503636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neu HM, Jung J, Baglia RA, Siegler MA, Ohkubo K, Fukuzumi S, Goldberg DP. Light-Driven, Proton-Controlled, Catalytic Aerobic C-H Oxidation Mediated by a Mn(III) Porphyrinoid Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:4614–4617. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenthal J, Luckett TD, Hodgkiss JM, Nocera DG. Photocatalytic oxidation of hydrocarbons by a bis-iron(III)-µ-oxo Pacman porphyrin using O2 and visible light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:6546–6547. doi: 10.1021/ja058731s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahammed A, Gray HB, Meier-Callahan AE, Gross Z. Aerobic oxidations catalyzed by chromium corroles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1162–1163. doi: 10.1021/ja028216j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prokop KA, Goldberg DP. Generation of an Isolable, Monomeric Manganese(V)-Oxo Complex from O2 and Visible Light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:8014–8017. doi: 10.1021/ja300888t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warren JJ, Tronic TA, Mayer JM. Thermochemistry of proton-coupled electron transfer reagents and its implications. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:6961–7001. doi: 10.1021/cr100085k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jung J, Ohkubo K, Prokop-Prigge KA, Neu HM, Goldberg DP, Fukuzumi S. Photochemical Oxidation of a Manganese(III) Complex with Oxygen and Toluene Derivatives to Form a Manganese(V)-Oxo Complex. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:13594–13604. doi: 10.1021/ic402121j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan X, Kirmaier C, Holten D. A picosecond study of rapid multistep radiationless decay in manganese(III) porphyrins. Inorg. Chem. 1986;25:4774–4777. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jung JE, Ohkubo K, Goldberg DP, Fukuzumi S. Photocatalytic Oxygenation of 10-Methyl-9,10-dihydroacridine by O2 with Manganese Porphyrins. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2014;118:6223–6229. doi: 10.1021/jp505860f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prokop KA, de Visser SP, Goldberg DP. Unprecedented Rate Enhancements of Hydrogen-Atom Transfer to a Manganese(V)-Oxo Corrolazine Complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:5091–5095. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neu HM, Quesne MG, Yang TS, Prokop-Prigge KA, Lancaster KM, Donohoe J, DeBeer S, de Visser SP, Goldberg DP. Dramatic Influence of an Anionic Donor on the Oxygen-Atom Transfer Reactivity of a Mn-V-Oxo Complex. Chem. Eur. J. 2014;20:14584–14588. doi: 10.1002/chem.201404349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neu HM, Yang TH, Baglia RA, Yosca TH, Green MT, Quesne MG, de Visser SP, Goldberg DP. Oxygen-Atom Transfer Reactivity of Axially Ligated Mn(V)-Oxo Complexes: Evidence for Enhanced Electrophilic and Nucleophilic Pathways. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:13845–13852. doi: 10.1021/ja507177h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandimutsira BS, Ramdhanie B, Todd RC, Wang H, Zareba AA, Czernuszewicz RS, Goldberg DP. A stable manganese(V)-oxo corrolazine complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:15170–15171. doi: 10.1021/ja028651d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prokop KA, Neu HM, de Visser SP, Goldberg DP. A Manganese(V)-Oxo pi-Cation Radical Complex: Influence of One-Electron Oxidation on Oxygen-Atom Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:15874–15877. doi: 10.1021/ja2066237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakazawa J, Ogiwara H, Kashiwazaki Y, Ishii A, Imamura N, Samejima Y, Hikichi S. Dioxygen Activation and Substrate Oxygenation by a p-Nitrothiophenolatonickel Complex: Unique Effects of an Acetonitrile Solvent and the p-Nitro Group of the Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:9933–9935. doi: 10.1021/ic201555f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukuzumi S, Kotani H, Prokop KA, Goldberg DP. Electron- and Hydride-Transfer Reactivity of an Isolable Manganese(V)-Oxo Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:1859–1869. doi: 10.1021/ja108395g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leeladee P, Baglia RA, Prokop KA, Latifi R, de Visser SP, Goldberg DP. Valence Tautomerism in a High-Valent Manganese-Oxo Porphyrinoid Complex Induced by a Lewis Acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:10397–10400. doi: 10.1021/ja304609n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baglia RA, Durr M, Ivanović-Burmazović I, Goldberg DP. Activation of a High-Valent Manganese-Oxo Complex by a Nonmetallic Lewis Acid. Inorg. Chem. 2014;53:5893–5895. doi: 10.1021/ic500901y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaragoza JPT, Baglia RA, Siegler MA, Goldberg DP. Strong Inhibition of O-Atom Transfer Reactivity for MnIV(O)(π-Radical-Cation)(Lewis Acid) versus MnV(O) Porphyrinoid Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:6531–6540. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]