Summary

This brief overview of endocytic trafficking is written in honor of Renate Fuchs, who retires this year. In the mid-80s, Renate pioneered studies on the ion-conducting properties of the recently discovered early and late endosomes and the mechanisms governing endosomal acidification. As described in this review, after uptake through one of many mechanistically distinct endocytic pathways, internalized proteins merge into a common early/sorting endosome. From there they again diverge along distinct sorting pathways, back to the cell surface, on to the trans-Golgi network or across polarized cells. Other transmembrane receptors are packaged into intraluminal vesicles of late endosomes/multivesicular bodies that eventually fuse with and deliver their content to lysosomes for degradation. Endosomal acidification, in part, determines sorting along this pathway. We describe other sorting machinery and mechanisms, as well as the rab proteins and phosphatidylinositol lipids that serve to dynamically define membrane compartments along the endocytic pathway.

Keywords: Endocytosis, clathrin mediated endocytosis, caveolae mediated endocytosis, clathrin-independent endocytosis, endosomes, endocytic trafficking, Rabs, Rab proteins, phosphatidylinositol phospholipids, multivesicular bodies, clathrin-dependent endocytosis

Introduction

Endocytosis, the process by which cells internalize macromolecules and surface proteins, was first discovered with the advancement of electron microscopy that enabled visualization of the specialized membrane domains responsible for two mechanistically and morphologically distinct pathways: clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) [1] and caveolae uptake [2] (see Table 1 for a glossary of terms and abbreviations used in this review). Selective inhibition of these two pathways later led to the discovery of cholesterol-sensitive clathrin- and caveolae-independent pathways [3–5], and more recently, the large capacity pathway involving clathrin independent carriers (CLIC) and glycophosphatidylinositol-anchored protein-enriched endosomal compartments (GEEC), termed the CLIC/GEEC pathway [6].

Table 1.

Glossary of terms and abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Term/Definition | Role/Function |

|---|---|---|

| AP2 | Adaptor Protein 2 | Recruits clathrin and cargo to growing clathrin coated pits |

| Arf6-dependent pathway | ADP-ribosylation factor 6 -dependent pathway | A clathrin-independent endocytic pathway |

| BAR domain-containing proteins | Bin/Amphiphysin/Rvs domain-containing proteins | proteins that can sense and generate membrane curvature |

| CavME | Caveolae-Mediated Endocytosis | An endocytic pathway |

| CCP/CCV | Clathrin-Coated Pit or Vesicle | The vehicles of clathrin-mediated endocytosis |

| CLASP | Clathrin Associated Sorting Proteins | Cargo specific adaptor proteins that work together with AP2 complexes |

| CIE | Clathrin-Independent Endocytosis | Describes alternate routes of endocytosis |

| CLIC/GEEC pathway | CLathrin-Independent Carriers, GPI-AP-Enriched Endocytic Compartments | A clathrin-independent endocytic pathway |

| CME | Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis | The major pathway for endocytic uptake |

| EEA1 | Early Endosome Antigen 1 | An early endosome associated scaffold protein |

| ESCRT | Endosomal Sorting Complexes Required for Transport | 4 complexes mediate formation in intraluminal vesicles during endosome maturation |

| FVYE domain | Fab-1, YGL023, Vps27, and EEA1 domain | Protein domain that interacts with PI(3)P a phosphatidyl inositol lipid |

| GAP | GTPase-Activating Protein | Inactivates small GTPases by catalyzing GTP hydrolysis |

| GEF | Guanine nucleotide Exchange Factor | Activated small GTPases by catalyzing GTP/GDP binding |

| GPI-AP | Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored Proteins | endocytic cargo |

| HSC70 | Heat Shock Cognate 70 | Also functions as the uncoating ATPase, to disassemble clathrin |

| ILV | Intraluminal Vesicle | Substructure of early/late endosomes. Sorts transmembrane cargo for degradation in lysosomes |

| MVB | Multivesicular body | A late endosome with cargo sorted into intraluminal vesicles for delivery to lysosomes |

| PH domain | Pleckstrin Homology domain | Protein domains that mediate specific PIP interactions |

| PIP | Phosphatidylinositol phospholipid | A phospholipid species readily interconvertable by phosphorylation/dephosphorylatio of the inositol head group |

| PI(4,5)P2 | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisPhosphate | Phospholipid component enriched in the plasma membrane |

| PI(3) | Phosphatidylinositol-3-Phosphate | Phospholipid component enriched in early endosome membranes |

| PX domain | PhoX homology domain | Protein domain required for specific PIP interactions |

| SH3 domain | SRC Homology 3 domain | Protein domains required for protein-protein interaction |

| SNX | Sorting Nexin family Proteins | Scaffolding and curvature generating proteins involved in endocytic trafficking |

| TGN | Trans-Golgi Network | A post-Golgi sorting compartment |

After molecules have been internalized through one of these different endocytic pathways they traffic through and are sorted by a pleiomorphic series of tubulovesicular compartments, collectively called endosomes [7]. Internalized macromolecules and surface proteins can have many different fates: They can be recycled back to the plasma membrane, delivered to the lysosomes for degradation, or in polarized cells sent across the cell through a process called transcytosis, which is important for transport across epithelia, endothelia and the blood brain barrier [8]. Endosomal compartments undergo maturation from early to late endosomes, which involves decreasing luminal pH, altering key phosphatidylinositol lipids through regulation by lipid kinases and phosphatases, and differential recruitment and activation of Rab-family GTPases.

Following the initial discovery of these pathways and their trafficking, it was then determined that each endocytic pathway fulfills multiple critical cellular functions. Cells communicate with each other and their environment through endocytosis. Consequently, endocytosis regulates the levels of many essential surface proteins and transporters in human health and disease, such as the glucose transporters that maintain serum glucose levels, proton pumps that control stomach acidification, or sodium channels that control cell homeostasis [9]. Furthermore, endocytosis regulates signaling from surface receptors like G-protein coupled receptors [10] and receptor tyrosine kinases [11]. Finally, endocytosis regulates cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions through uptake of integrins and adhesion molecules [12]. Since the discovery of endocytosis several decades ago, its complex and critical role in human physiology and pathology has become increasingly appreciated and better understood. This review briefly summarizes our current state of knowledge about cargo sorting and trafficking along the endocytic pathway.

Multiple Mechanisms for uptake into cells

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis

The most studied and hence, well-characterized endocytic mechanism is clathrin-mediated endocytosis (Figure 1), which occurs through clathrin-coated pits (CCPs) and clathrin coated vesicles (CCVs), first observed >50 years ago by thin section electron microscopy [1]. CME was first found to play an important role in low-density lipoprotein [13] and transferrin uptake [14] upon binding to their respective receptors (hereafter referred to as ‘cargo’). The principle components of the CCVs are the heavy and light chains of clathrin [15], from which the pathway acquires its name, and the four subunits of the heterotetrameric adaptor protein 2 (AP2) complex [16]. The AP2 complex links the clathrin coat to the membrane bilayer and is also the principle cargo-recognition molecule [17]. There are other specialized adaptor proteins, collectively called “CLASPs” (for clathrin associated sorting proteins) [18, 19], which each recognize distinct sorting motifs on their respective cargo receptors. These cargo-specific adaptor proteins often interact with both clathrin and the AP2 complex, increasing the repertoire of cargo that can be sorted.

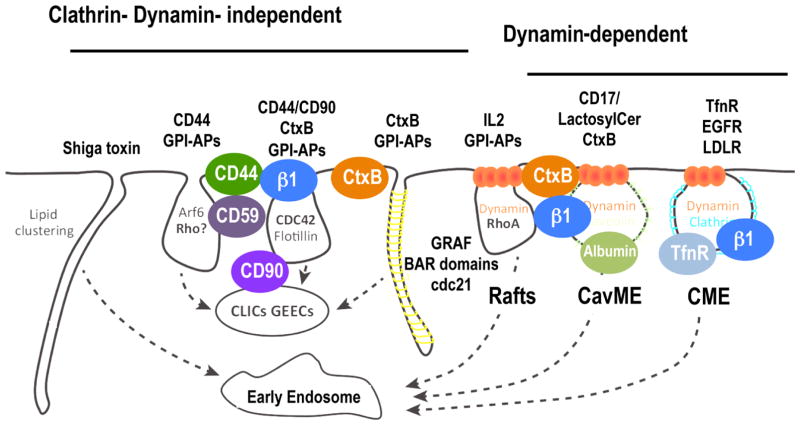

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the different endocytic pathways described in mammalian cells. The pathways can be broken into two main groups, dynamin-dependent and clathrin- and dynamin-independent pathways. Ligands known to traffic through each pathway, some of which have disease implications, are labeled along with the important molecular players of each pathway. The representation was inspired by [93].

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis proceeds through multiple stages: CCP initiation, cargo-selection, CCP growth and maturation, scission and CCV release, and, finally, uncoating. CCP assembly is initiated by AP2 complexes that are recruited to the plasma membrane-enriched phosphatidylinositol lipid, PI(4,5)P2 [19]. AP2 complexes then rapidly recruit clathrin [20]. Other scaffolding molecules (e.g. FCHo, eps15, and/or intersectins) also assemble early and may play a role in either nucleating and/or stabilizing nascent CCPs [20, 21]. Although clathrin has been shown to spontaneously assemble into closed cages in vitro [22], in cells, other curvature generating proteins must be recruited to nascent CCP’s for efficient budding. For example, the intrinsically curved, BAR (Bin-Amphiphysin-Rvs) domain-containing proteins can create increasingly deeper curvature and are thought to be required for progression of the clathrin-coated pit [23]. As the nascent pits grow, AP2 and other cargo-specific adaptor proteins recruit and concentrate cargo. Clathrin polymerization stabilizes the curvature of the pit; however other factors recruited to AP2 complexes are also required for efficient curvature generation and their subsequent invagination [24].

Release of mature clathrin-coated vesicles from the plasma membrane depends on the large GTPase dynamin [25]. Dynamin is recruited to clathrin-coated pits by BAR domain-containing proteins [26] such as amphiphysin, endophilin, and sorting nexin 9, which also encode SRC homology 3 (SH3) domains that bind to dynamin’s proline-rich domain. Dynamin assembles into collar-like structures encircling the necks of deeply invaginated pits and undergoes GTP hydrolysis to drive membrane fission [25]. Finally, once the vesicle is detached from the plasma membrane the clathrin coat is disassembled by the ATPase, heat shock cognate 70 (HSC70) and its cofactor auxilin [27, 28]. This allows the now uncoated vesicle to travel and fuse with its target endosome.

Caveolae-mediated endocytosis

Caveolae-mediated endocytosis (CavME), which was also first discovered ~60 years ago by thin section electron microscopy [2], is the second most well-characterized and studied endocytic pathway (Figure 1). CavME has been found to be important in transcytotic trafficking across endothelia as well as mechanosensing and lipid regulation [29]. Caveolae, the site of CavME, are flask or omega-shaped plasma membrane invaginations with a diameter of 50–100 nm and are abundantly present on many but not all eukaryotic plasma membranes [30]. Biochemical studies have revealed that caveolae are detergent resistant, highly hydrophobic membrane domains enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids [31, 32]. In addition to their role in endocytosis, caveolae have been implicated as signaling platforms, regulators of lipid metabolism and in cell surface tension sensing [33].

The main structural proteins of caveolae are members of the caveolin protein family, the most common being caveolin-1. Caveolin-1 is a small integral membrane protein that is inserted into the inner leaflet of the membrane bilayer. The cytosolic N-terminal region of caveolin-1 binds to cholesterol and functions as a scaffolding domain that binds to important signaling molecules [33]. Once thought to be sufficient for the formation of caveolae, it is now known that caveolins co-assemble with cytosolic coat proteins, called cavins, to form these structures [34].

Live cell microscopy studies have revealed that caveolae are static structures and that CavMe is highly regulated and triggered by ligand binding to cargo receptors concentrated in caveolae [29]. The steps involved in CavME are not as well understood as those involved in CME. However, budding of caveolae from the plasma membrane is known to be regulated by kinases and phosphatases [35], as numerous studies have shown that their chemical inhibition either inhibits (in the case of kinase inhibitors) or enhances (in the case of phosphatase inhibitors) CavME [36, 37]. Finally, like CME, dynamin is required to pinch off caveolae vesicles from the plasma membrane [38].

Clathrin-independent endocytosis

More recently, it has become clear that other mechanistically distinct endocytic pathways mediate uptake of different subsets of signaling, adhesion and nutrient receptors, as well as regulate the surface expression of membrane transporters. These pathways have been shown to be clathrin-independent endocytic (CIE) pathways, and as the name infers, the endocytic vesicles/tubules involved in CIE have no distinct coat and are not easily detected by EM. Thus, these pathways were first discovered by virtue of their resistance to inhibitors that block CME and CavME [3, 4, 39].

The term CIE encompasses several pathways (Figure 1, reviewed in [40–42]): i) An endophilin-, dynamin- and RhoA-dependent pathway that was first identified for its role in interleukin-2 receptor endocytosis [5] and recently shown to mediate uptake of many other cytokine receptors and their constituents [43]. ii) A recently discovered clathrin- and dynamin-independent pathway that involves the small GTPases Rac1 and Cdc42 and leads to the actin-dependent formation of so-called clathrin-independent carriers (CLICs) [44], which fuse to form a specialized early endosomal compartment called the GPI-AP enriched endosomal compartments (GEECs) [6, 42]. Hence, this process is termed the CLIC/GEEC pathway. iii) A pathway depending on the small GTPase, Arf6, that was first shown to mediate uptake and recycling of the Major Histocompatibility Antigen I [41]. Arf6 activates phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase to produce PI(4,5)P2 to stimulate actin assembly and drive endocytosis [45]. And, iv) a pathway dependent on curvature-generating, membrane-anchored proteins, called flotillins [46, 47]. The degree of overlap of these pathways is still incompletely understood and, somewhat disputed [48]. Certainly, they carry overlapping cargo molecules, for example the GPI-anchored protein, CD59, is taken up by both the CLIC/GEEC and in a flottilin-dependent manner in HeLa cells. Similarly, the transmembrane protein, CD44 is a cargo of both the Arf6-pathway and the CLIC/GEEC pathway [49]. Thus, it remains unclear as to whether they represent mechanistically distinct pathways or cell type and/or experimentally induced variations of the same pathway. Additional molecular machinery and mechanistic insights are needed to resolve these issues and better define these pathways.

The role of these CIE pathways in the cell and the extent to which they contribute to the endocytic capacity of the cell remains unclear. Thus, whereas some studies suggest they are the major pathways for bulk uptake [6], other authors have suggested that CME can account for virtually all bulk uptake [50], inferring that CIE might be induced only upon disruption of CME. However, a recent survey of endocytic activities in 29 different non-small cell lung cancer cells revealed that CIE pathways are differentially regulated relative to CME and CavME, providing strong evidence for their autonomy and functional importance [51].

Endosomal Trafficking

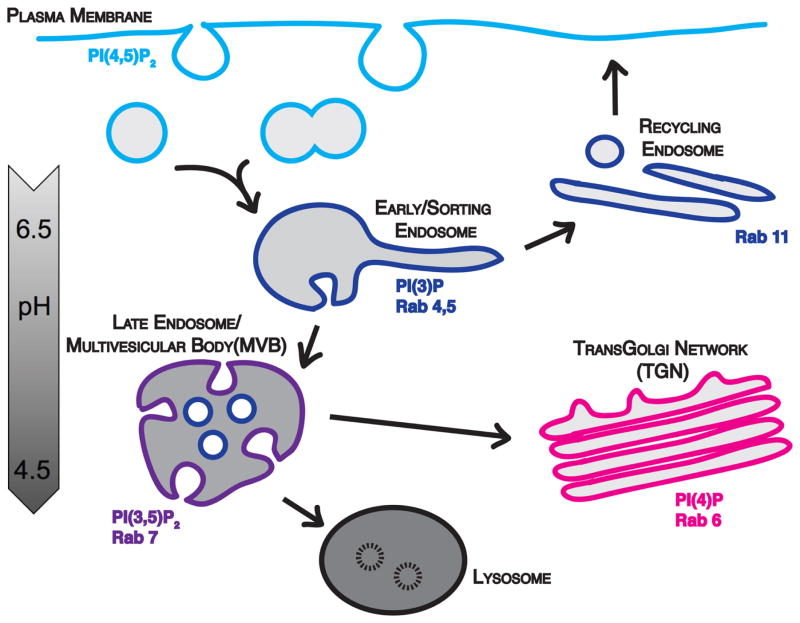

Once internalized into cells through any of the multiple endocytic pathways, cargoes (receptors and their bound ligands) then merge into the common endosomal network. The endosomal network is a dynamic and interconnected “highway” system that allows for the vectorial trafficking and transfer of cargoes between distinct membrane-bound compartments. The function of the endosomal network is to collect internalized cargoes, sort, and disseminate them to their final destinations [44]. Upon entering the cell, primary endocytic vesicles undergo multiple rounds of homotypic fusion [52] to form early/sorting endosomes. Within early endosomes initial sorting decisions are made and the fates of the internalized receptors are decided. Ultimately, cargoes can be recycled back to the plasma membrane, sent to the trans-Golgi network (TGN) via retrograde traffic, or sorted to the lysosome for degradation (Figure 2). The regulation of membrane traffic and cargo sorting is achieved through the tight spatial and temporal control of endosomal identity.

Figure 2.

Endosomal trafficking. Internalized vesicles undergo homotypic fusion to form early/sorting endosomes, which tubulate to facilitate cargo sorting. From here internalized cargo can be sorted and recycled back to the plasma membrane through the recycling endosome, sent to the trans-Golgi network (TGN) via retrograde trafficking mechanisms, or trafficked through the late endosome/multivesicular body (MVB) to the lysosome for degradation. As endosomes mature they increase in acidification (depicted in greyscale). Additionally, each endosomal compartment is defined by signature phosphatidylinositol phospholipids (PIPs) and Rab family GTPases.

Endosome Identity

Each compartment within the endosomal network has a unique identity. However, these identities are fluid and can be altered as molecules and cargoes are dynamically exchanged. This process is more widely recognized as endosomal maturation. Early endosomes mature to late endosomes through several mechanisms. Most notably, as endosomes mature their lumens becomes increasingly acidic. This is due to the actions of a v-type vacuolar H+ ATPase in the membrane bilayer, which pumps hydrogen ions into the vacuole lumen and decreases the pH [53, 54]. Other mechanisms have evolved to regulate the dynamic nature of these trafficking pathways and to control the directional flow of membrane trafficking, such as alterations in phosphatidylinositol phospholipids (PIPs), and the differential recruitment and activation of Rab family GTPases (For more information on Rabs, see Box 1).

Box 1. Rab proteins control membrane identity, function, and trafficking.

Rab GTPases are highly conserved small monomeric GTPases that have key roles in regulating membrane trafficking and the compartmentalization of the endomembrane system. The Rab GTPase family is the largest family within the Ras superfamily of small GTPases. Rabs contribute to the structural and functional identity of the endomembrane system through the recruitment of unique sets of effector proteins to the surfaces of distinct membrane compartments [63, 85, 94, 95]. This function relies heavily on the fact that Rab GTPases, similar to other Ras superfamily GTPases, function as “molecular switches” and cycle between GDP- and GTP-bound states. As Rab GTPases have low intrinsic rates of nucleotide exchange and hydrolysis, they require other proteins to help modulate the GTP-GDP cycle. Guanine-nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) catalyze the exchange and hydrolysis reactions, respectively [96]. Rab effectors preferentially bind to the GTP-bound and active form of Rab GTPases. The association of an active Rab GTPase and its effector protein allows for the formation of higher-order molecular assemblies, which define endomembrane identity as well as control vesicle formation, targeting, and fusion to ensure the directionality of transport. These Rab-centric protein complexes are reversible, as well as spatially and temporally regulated through the GTP-GDP cycle, to allow for the dynamic flux of endomembrane identity and the fidelity of cargo transport [97]. The proper spatiotemporal regulation of Rab GTPase activity is absolutely critical to maintaining vesicle trafficking throughout the cell.

Membrane compartments along the endocytic pathway are, in part, identified by their phosphatidylinositol phospholipid composition. PIPs are phosphorylated derivatives of phosphatidylinositol, which is synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum and delivered to other endomembrane compartments through membrane trafficking [55]. PIP segregation on distinct membranes is critical for the directional flow of membrane cargoes. Specific PIPs are enriched at distinct compartments through the regulated inter-conversion of PIP species by lipid kinases and phosphatases that mediate reversible phosphorylation/dephosphorylation at the 3, 4, and 5 positions of the inositol ring [55, 56]. Increasing evidence demonstrates that lipid distribution is important for the differential recruitment of proteins involved in trafficking to specific membrane compartments through PIP-specific lipid binding domains (Figure 2). Thus, as described above, many components of the CME pathway, including AP2 and dynamin, selectively bind to PI(4,5)P2, which is enriched at the plasma membrane. Similarly, FVYE domains (named after the four proteins, Fab1p, YOTB, Vac1p, EEA1, originally found to encode the domain) and PX domains (Phox homology) preferentially bind PI(3)P [57, 58], which is predominantly restricted to early endosomes and their intraluminal vesicles (ILVs, see Figure 2) [59, 60]. Distinct pleckstrin homology domains, also found on many endocytic proteins, can recognize either PI(4)P, PI(4,5)P2, or PI(3,4,5)P3 [58].

There is a close relationship between PIP modifying enzymes and Rab GTPases, the other molecular identifier of distinct endosomal compartments. For example, PIPs can recruit regulators of Rab proteins, i.e. guanine-nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) that activate Rabs and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) that inactivate them, to target membranes through the association of specific lipid-binding domains. In addition, PIP kinases and phosphatases are often Rab effectors. Thus, Rab5-dependent PI(3)P synthesis on early endosomes is regulated by the class III PI3-kinase VPS34 [61], a Rab5 effector [62, 63]. Additionally, several known Rab effectors have PI(3)P binding motifs, including early endosomal antigen 1 (EEA1), a well-characterized marker of early endosomes, which associates with PI(3)P through its FYVE domain. Thus, phosphoinositides and Rabs can coordinate membrane identity through both positive and negative feedback mechanisms [63, 64].

An important and emerging concept in endosomal maturation is domain or compartment conversion [65]. In this process, also known as a Rab cascade, an upstream Rab (e.g. Rab5) recruits a GEF that activates and recruits a downstream Rab (e.g. Rab7), which in turn recruits a GAP for the upstream Rab and, in this way, converts the membrane’s identity (e.g. from a Rab5 to a Rab7 domain). Thus, through a change in Rabs and their effector molecules, the membrane’s identify and function is altered.

Endosomal sorting mechanisms

As cargoes enter the endosomal network they are sorted in the early endosome towards their final destination. Early endosomal sorting depends initially on endosomal acidification and ligand dissociation. Internalized ligand-receptor complexes have different pH sensitivities for receptor-ligand dissociation [66]. This allows for the differential recycling of cell surface receptors. For example, receptors that recycle to the plasma membrane typically release their ligands in the early endosome, where the pH is maintained at ~6.5, in part through regulation by the circulating plasma membrane Na/K ATPase [54]. This allows for the rapid recycling of cell surface receptors such as the transferrin receptor or the low-density lipoprotein receptor. Cargoes that are destined for the trans-Golgi network release their ligands in the late endosomal pH range of ~5.5 (e.g. mannose-6-phosphate receptor). Conversely, signaling receptors (e.g. the epidermal growth factor receptor) often remain ligand bound and active, even at low (~4.5) pH. This can allow for their continual signaling from endosomal compartments until they are sorted into ILVs and sent for degradation in the lysosome [66].

In addition to pH, endosome geometry is important for sorting of internalized cargoes [67]. Early endosomes are highly dynamic and pleiomorphic structures. As early endosomes mature they can exhibit tubulation, which helps facilitate cargo sorting and recycling. The larger vacuolar portion of the early endosome is roughly spherical and ~100–500 nm in diameter [44]. This geometry maximizes the volume-to-surface area ratio and thus, as ligands dissociate from their receptor they accumulate in the lumen of these vacuolar regions. Conversely, the narrow tubules that extend from early endosomes have a maximum surface area-to-volume ratio. This allows for the accumulation of transmembrane receptors destined for recycling. In some cells the tubules released from early/sorting endosomes accumulate in the perinuclear region before returning to the cell surface, forming the recycling endosome [44, 67].

In addition to physical sorting by pH and geometry, it was discovered that efficient endocytic cargo recycling depends on the active association of sorting machinery with sorting signals encoded within the amino acid sequences of cargo molecules [68]. These active sorting interactions typically occur along endosomal tubules. Endosomal membrane tubulation is driven by proteins with lipid-binding motifs, such as BAR domain-containing proteins, that can induce membrane curvature. Sorting nexin family proteins (SNXs) also interact with endosomal membranes, induce tubulation and control cargo sorting [69]. Several SNX family members are involved in cargo sorting as part of the evolutionarily conserved retromer complex [68, 70]. The retromer complex was discovered in yeast, as being required for retrograde transport of the trans-Golgi sorting receptor, Vps10, from endosomes to the TGN [71, 72]. Later, biochemical and cell biology studies demonstrated the conservation of this complex in mammals and uncovered the molecular mechanisms of action. The retromer complex can be divided into two functionally distinct subcomplexes: the membrane recognition and deformation complex comprised of BAR domain-containing sorting nexins (SNX 1/2 or SNX 5/6 in mammals, or Vps 5 and 17, in yeast), and the cargo-selective complex comprised of Vps26, Vps29, and Vps35 [70]. The retromer complex is recruited to endosomes through SNX-mediated PI(3)P binding and/or association with Rab7-positive late endosomes through Vps35-Rab7 interactions [70]. Retromer complexes function to “rescue” cargo receptors (e.g. the mannose-6-phosphate receptor that carries newly synthesized lysosomal hydrolases from the TGN to the endo/lysosomal system) from the degradative lysosomal pathway and divert them for recycling to the plasma membrane or the trans-Golgi network.

Other mechanisms of active cargo sorting within the endosomal network have been discovered [68]. One example is the sorting of ubiquitinated cargoes, such as the signaling epidermal growth factor receptor, into intraluminal vesicles for lysosomal degradation. As early endosomes mature they can accumulate intraluminal vesicles in their vacuolar portions through the inward budding of the limiting membrane [73, 74]. These ILVs increase in number as endosomes mature to become late endosomes/multivesicular bodies. Sorting into ILVs is mediated by the multi-subunit ESCRT (endosomal sorting complexes required for transport) machinery. The ESCRT complex family is comprised of four different protein complexes, ESCRTs −0, −I, −II, −III, and Vps4, a member of the AAA-ATPase (ATPases associated with various cellular activities) family that functions to disassemble the ESCRT complexes to complete the process. These complexes act together to recognize and sort ubiquitinated cargoes, and drive the formation of cargo-containing ILVs [73–75]. Upon late endosome-lysosome fusion the ILVs are exposed to and degraded by lysosomal hydrolyses (lipases and proteases).

Endocytosis in Human Disease

The loss of function of any of the central components of CME such as: clathrin, AP2, and dynamin result in embryonic lethality [26, 76, 77]. Therefore, severe mutations of the key players are not seen in human disease. However, several perturbations of CME have been reported in numerous human diseases such as cancer, myopathies, neuropathies, metabolic genetic syndromes, and psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases [18]. Likewise, core components of CavME have been shown to be altered in cancer [78–80] and CavME has been suggested to play a role in a variety of diseases including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and myopathies. Because of the different cargo trafficked in a clathrin independent manner which are important for cell survival [46], signaling [81] and migration [82] and their regulation by small GTPases, the CIE pathway is also thought to be deregulated in human diseases, specifically cancer [48]. However, since so little is currently known about these pathways, more research is needed to fully understand their physiological importance.

Given the ubiquitous and critical nature of endocytosis, it has been usurped for both good and bad. Thus, viruses and toxins specifically target different endocytic pathways to invade the cell [83], and as more becomes known about the different pathways of endocytosis, researchers are developing methods to specifically target and deliver nanoparticles and therapeutics to diseased cells [84].

Mutations in Rabs [85–88], lipid phosphatases [89] and kinases [55, 56], and other components of the endosomal trafficking and sorting machinery are also linked to many human diseases [12, 90–92]. Though we have gained much insight into the molecular mechanisms of endosomal trafficking, there are still gaps in our knowledge of how cells have evolved specialized mechanisms of cargo detection, sorting, and trafficking. A deeper understanding of these mechanisms will lead to a better understanding of the link between endocytic membrane trafficking and human pathology.

Acknowledgments

Support: This work was supported by the following sources: HHMI Med into Grad Grant (Grant#56006776) to the Mechanisms of Disease and Translational Science Track supported by NIH T32 (Grant# 1T32GM10977601), The Pharmacological Sciences Training Grant GM00706240, NIH RO1 (5R01MH61345), and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award Number TL1TR001104.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Roth TF, Porter KR. Yolk Protein Uptake in the Oocyte of the Mosquito Aedes Aegypti. L. J Cell Biol. 1964;20:313–32. doi: 10.1083/jcb.20.2.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamada E. The fine structure of the gall bladder epithelium of the mouse. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1955;1(5):445–58. doi: 10.1083/jcb.1.5.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moya M, et al. Inhibition of coated pit formation in Hep2 cells blocks the cytotoxicity of diphtheria toxin but not that of ricin toxin. J Cell Biol. 1985;101(2):548–59. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.2.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansen SH, Sandvig K, van Deurs B. The preendosomal compartment comprises distinct coated and noncoated endocytic vesicle populations. J Cell Biol. 1991;113(4):731–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.4.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamaze C, et al. Interleukin 2 receptors and detergent-resistant membrane domains define a clathrin-independent endocytic pathway. Mol Cell. 2001;7(3):661–71. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirkham M, et al. Ultrastructural identification of uncoated caveolin-independent early endocytic vehicles. J Cell Biol. 2005;168(3):465–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott CC, Vacca F, Gruenberg J. Endosome maturation, transport and functions. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;31:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Preston JE, Joan Abbott N, Begley DJ. Transcytosis of macromolecules at the blood-brain barrier. Adv Pharmacol. 2014;71:147–63. doi: 10.1016/bs.apha.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antonescu CN, McGraw TE, Klip A. Reciprocal regulation of endocytosis and metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(7):a016964. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irannejad R, von Zastrow M. GPCR signaling along the endocytic pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;27:109–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goh LK, Sorkin A. Endocytosis of receptor tyrosine kinases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(5):a017459. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a017459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mellman I, Yarden Y. Endocytosis and cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(12):a016949. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carpentier JL, et al. Co-localization of 125I-epidermal growth factor and ferritin-low density lipoprotein in coated pits: a quantitative electron microscopic study in normal and mutant human fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1982;95(1):73–7. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neutra MR, et al. Intracellular transport of transferrin- and asialoorosomucoid-colloidal gold conjugates to lysosomes after receptor-mediated endocytosis. J Histochem Cytochem. 1985;33(11):1134–44. doi: 10.1177/33.11.2997327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson MS. Forty Years of Clathrin-coated Vesicles. Traffic. 2015 doi: 10.1111/tra.12335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirchhausen T, Owen D, Harrison SC. Molecular structure, function, and dynamics of clathrin-mediated membrane traffic. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(5):a016725. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirchhausen T. Adaptors for clathrin-mediated traffic. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:705–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McMahon HT, Boucrot E. Molecular mechanism and physiological functions of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(8):517–33. doi: 10.1038/nrm3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Traub LM, Bonifacino JS. Cargo recognition in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(11):a016790. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cocucci E, et al. The first five seconds in the life of a clathrin-coated pit. Cell. 2012;150(3):495–507. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henne WM, et al. FCHo proteins are nucleators of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Science. 2010;328(5983):1281–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1188462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woodward MP, Roth TF. Coated vesicles: characterization, selective dissociation, and reassembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75(9):4394–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.9.4394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qualmann B, Koch D, Kessels MM. Let’s go bananas: revisiting the endocytic BAR code. EMBO J. 2011;30(17):3501–15. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aguet F, et al. Advances in analysis of low signal-to-noise images link dynamin and AP2 to the functions of an endocytic checkpoint. Dev Cell. 2013;26(3):279–91. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmid SL, V, Frolov A. Dynamin: functional design of a membrane fission catalyst. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:79–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson SM, et al. Coordinated actions of actin and BAR proteins upstream of dynamin at endocytic clathrin-coated pits. Dev Cell. 2009;17(6):811–22. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothman JE, Schmid SL. Enzymatic recycling of clathrin from coated vesicles. Cell. 1986;46(1):5–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90852-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ungewickell E, et al. Role of auxilin in uncoating clathrin-coated vesicles. Nature. 1995;378(6557):632–5. doi: 10.1038/378632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parton RG, Simons K. The multiple faces of caveolae. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(3):185–94. doi: 10.1038/nrm2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pelkmans L, Helenius A. Endocytosis via caveolae. Traffic. 2002;3(5):311–20. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.30501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murata M, et al. VIP21/caveolin is a cholesterol-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(22):10339–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harder T, Simons K. Caveolae, DIGs, and the dynamics of sphingolipid-cholesterol microdomains. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9(4):534–42. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parton RG, del Pozo MA. Caveolae as plasma membrane sensors, protectors and organizers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14(2):98–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm3512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nassar ZD, Parat MO. Cavin Family: New Players in the Biology of Caveolae. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2015;320:235–305. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiss AL. Caveolae and the regulation of endocytosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;729:14–28. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-1222-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li S, Seitz R, Lisanti MP. Phosphorylation of caveolin by src tyrosine kinases. The alpha-isoform of caveolin is selectively phosphorylated by v-Src in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(7):3863–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parton RG, Joggerst B, Simons K. Regulated internalization of caveolae. J Cell Biol. 1994;127(5):1199–215. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.5.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henley JR, et al. Dynamin-mediated internalization of caveolae. J Cell Biol. 1998;141(1):85–99. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandvig K, van Deurs B. Selective modulation of the endocytic uptake of ricin and fluid phase markers without alteration in transferrin endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(11):6382–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doherty GJ, McMahon HT. Mechanisms of endocytosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:857–902. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081307.110540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donaldson JG, Jackson CL. ARF family G proteins and their regulators: roles in membrane transport, development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(6):362–75. doi: 10.1038/nrm3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayor S, Parton RG, Donaldson JG. Clathrin-independent pathways of endocytosis. In: Schmid ASSL, Zerial M, editors. Endocytosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol; 2016. pii: a016758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boucrot E, et al. Endophilin marks and controls a clathrin-independent endocytic pathway. Nature. 2015;517(7535):460–5. doi: 10.1038/nature14067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huotari J, Helenius A. Endosome maturation. EMBO J. 2011;30(17):3481–500. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Radhakrishna H, Donaldson JG. ADP-ribosylation factor 6 regulates a novel plasma membrane recycling pathway. J Cell Biol. 1997;139(1):49–61. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glebov OO, Bright NA, Nichols BJ. Flotillin-1 defines a clathrin-independent endocytic pathway in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(1):46–54. doi: 10.1038/ncb1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frick M, et al. Coassembly of flotillins induces formation of membrane microdomains, membrane curvature, and vesicle budding. Curr Biol. 2007;17(13):1151–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mayor S, Parton RG, Donaldson JG. Clathrin-independent pathways of endocytosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(6) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maldonado-Baez L, Williamson C, Donaldson JG. Clathrin-independent endocytosis: a cargo-centric view. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319(18):2759–69. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bitsikas V, I, Correa R, Jr, Nichols BJ. Clathrin-independent pathways do not contribute significantly to endocytic flux. Elife. 2014;3:e03970. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elkin SR, et al. A Systematic Analysis Reveals Heterogeneous Changes in the Endocytic Activities of Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2015;75(21):4640–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salzman NH, Maxfield FR. Intracellular fusion of sequentially formed endocytic compartments. J Cell Biol. 1988;106(4):1083–91. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.4.1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mellman I, Fuchs R, Helenius A. Acidification of the endocytic and exocytic pathways. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:663–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.003311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fuchs R, Male P, Mellman I. Acidification and ion permeabilities of highly purified rat liver endosomes. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(4):2212–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Di Paolo G, De Camilli P. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature. 2006;443(7112):651–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bissig C, Gruenberg J. Lipid sorting and multivesicular endosome biogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(10):a016816. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lemmon MA. Phosphoinositide recognition domains. Traffic. 2003;4(4):201–13. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2004.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Balla T. Inositol-lipid binding motifs: signal integrators through protein-lipid and protein-protein interactions. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 10):2093–104. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gillooly DJ, et al. Localization of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate in yeast and mammalian cells. EMBO J. 2000;19(17):4577–88. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klumperman J, Raposo G. The complex ultrastructure of the endolysosomal system. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(10):a016857. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schu PV, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase encoded by yeast VPS34 gene essential for protein sorting. Science. 1993;260(5104):88–91. doi: 10.1126/science.8385367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Odorizzi G, Babst M, Emr SD. Phosphoinositide signaling and the regulation of membrane trafficking in yeast. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25(5):229–35. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01543-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zerial M, McBride H. Rab proteins as membrane organizers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(2):107–17. doi: 10.1038/35052055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shin HW, et al. An enzymatic cascade of Rab5 effectors regulates phosphoinositide turnover in the endocytic pathway. J Cell Biol. 2005;170(4):607–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Novick P, Zerial M. The diversity of Rab proteins in vesicle transport. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9(4):496–504. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mellman I. Endocytosis and molecular sorting. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:575–625. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maxfield FR, McGraw TE. Endocytic recycling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5(2):121–32. doi: 10.1038/nrm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hsu VW, Bai M, Li J. Getting active: protein sorting in endocytic recycling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(5):323–8. doi: 10.1038/nrm3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Weering JR, et al. Molecular basis for SNX-BAR-mediated assembly of distinct endosomal sorting tubules. EMBO J. 2012;31(23):4466–80. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Burd C, Cullen PJ. Retromer: a master conductor of endosome sorting. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(2) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Seaman MN, et al. Endosome to Golgi retrieval of the vacuolar protein sorting receptor, Vps10p, requires the function of the VPS29, VPS30, and VPS35 gene products. J Cell Biol. 1997;137(1):79–92. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Seaman MN, McCaffery JM, Emr SD. A membrane coat complex essential for endosome-to-Golgi retrograde transport in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1998;142(3):665–81. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Babst M. MVB vesicle formation: ESCRT-dependent, ESCRT-independent and everything in between. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23(4):452–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hurley JH, Hanson PI. Membrane budding and scission by the ESCRT machinery: it’s all in the neck. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(8):556–66. doi: 10.1038/nrm2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Henne WM, Stenmark H, Emr SD. Molecular mechanisms of the membrane sculpting ESCRT pathway. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(9) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mitsunari T, et al. Clathrin adaptor AP-2 is essential for early embryonal development. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(21):9318–23. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9318-9323.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Royle SJ. The cellular functions of clathrin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63(16):1823–32. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5587-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Song Y, et al. Caveolin-1 knockdown is associated with the metastasis and proliferation of human lung cancer cell line NCI-H460. Biomed Pharmacother. 2012;66(6):439–47. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhan P, et al. Expression of caveolin-1 is correlated with disease stage and survival in lung adenocarcinomas. Oncol Rep. 2012;27(4):1072–8. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sunaga N, et al. Different roles for caveolin-1 in the development of non-small cell lung cancer versus small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64(12):4277–85. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Le Roy C, Wrana JL. Clathrin- and non-clathrin-mediated endocytic regulation of cell signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(2):112–26. doi: 10.1038/nrm1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Howes MT, et al. Clathrin-independent carriers form a high capacity endocytic sorting system at the leading edge of migrating cells. J Cell Biol. 2010;190(4):675–91. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201002119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cossart P, Helenius A. Endocytosis of viruses and bacteria. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(8) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Adjei IM, Sharma B, Labhasetwar V. Nanoparticles: cellular uptake and cytotoxicity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;811:73–91. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-8739-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(8):513–25. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Seabra MC, Mules EH, Hume AN. Rab GTPases, intracellular traffic and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02227-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cheng KW, et al. Emerging role of RAB GTPases in cancer and human disease. Cancer Res. 2005;65(7):2516–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hutagalung AH, Novick PJ. Role of Rab GTPases in membrane traffic and cell physiology. Physiol Rev. 2011;91(1):119–49. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00059.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sharma S, Skowronek A, Erdmann KS. The role of the Lowe syndrome protein OCRL in the endocytic pathway. Biol Chem. 2015;396(12):1293–300. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2015-0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Esposito G, Ana Clara F, Verstreken P. Synaptic vesicle trafficking and Parkinson’s disease. Dev Neurobiol. 2012;72(1):134–44. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jiang S, et al. Trafficking regulation of proteins in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:6. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Goldenring JR. A central role for vesicle trafficking in epithelial neoplasia: intracellular highways to carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(11):813–20. doi: 10.1038/nrc3601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gauthier NC, Masters TA, Sheetz MP. Mechanical feedback between membrane tension and dynamics. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22(10):527–35. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wandinger-Ness A, Zerial M. Rab proteins and the compartmentalization of the endosomal system. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(11):a022616. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pfeffer SR. Rab GTPase regulation of membrane identity. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25(4):414–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Barr F, Lambright DG. Rab GEFs and GAPs. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22(4):461–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gurkan C, et al. Large-scale profiling of Rab GTPase trafficking networks: the membrome. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(8):3847–64. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]