Abstract

Background

We assessed the evidence for association between 23 recently reported prostate cancer (PCa) variants and early-onset PCa and the aggregate value of 63 PCa variants for predicting early-onset disease using 931 unrelated men diagnosed with PCa prior to age 56 years and 1126 male controls.

Methods

Logistic regression models were used to test the evidence for association between the 23 new variants and early-onset PCa. Weighted and unweighted sums of total risk alleles across these 23 variants and 40 established variants were constructed. Weights were based on previously reported effect size estimates. Receiver operating characteristic curves and forest plots, using defined cut-points, were constructed to assess the predictive value of the burden of risk alleles on early-onset disease.

Results

Ten of the 23 new variants demonstrated evidence (p < 0.05) for association with early-onset PCa, including four that were significant after multiple test correction. The aggregate burden of risk alleles across the 63 variants was predictive of early-onset PCa (Area Under Curve = 0.71 using weighted sums), especially in men with a high burden of total risk alleles.

Conclusions

A high burden of risk alleles is strongly associated with early-onset PCa.

Impact

Our results provide the first formal replication for several of these 23 new variants and demonstrate that a high burden of common-variant risk alleles is a major risk factor for early-onset PCa.

Keywords: early-onset prostate cancer, GWAS, aggregate risk

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second leading cause of cancer mortality in men in the United States. In 2014, it is estimated that 233,000 men would be diagnosed with PCa and 29,480 men would die from the disease (1). The major recognized risk factors for PCa are increasing age, African ancestry, and positive family history.

Approximately 10% of men diagnosed with PCa in the United States are diagnosed with the disease prior to age 56 years (1). Men with early-onset PCa are more likely to be aggressively treated for their disease and more likely to die from their disease compared to men diagnosed with PCa later in life with similar clinical characteristics (2-4). As with most cancers, early intervention in men that need it can significantly increase the rate of survival. Given the controversy surrounding prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing, identifying subsets of men that would most likely benefit from early screening would have a major impact on the successful treatment of the disease. Early-onset disease is also an indicator for heritable disease (2,4,5). An important question is whether we can use the cumulative information across associated variants to reasonably predict who is most likely to be diagnosed with early-onset PCa.

To date, genome-wide association studies (GWAS), including primarily older men with PCa, have identified more than 60 distinct common loci with modest effects associated with the disease in men of European descent, including 23 new loci identified using 19,662 PCa cases and 19,715 controls included in the PRACTICAL consortium (6-20). Several studies have demonstrated the importance of the previously established common variants to early-onset and familial PCa (12,21-25). Herein, we first test whether these 23 new variants are associated with early-onset PCa (20). We then assess the aggregate value of these 23 new variants, aggregate value of these new variants plus 40 established variants, and the added value of including information from these 23 new variants to the overall burden of risk alleles from the 40 established variants in predicting early-onset PCa. We demonstrate that the total risk-allele burden across PCa GWAS variants can be useful for identifying a subset of men with substantially increased risk for early-onset disease.

Materials and Methods

Study Samples

This study includes 931 unrelated early-onset PCa cases (diagnosed prior to age 56 years) of European descent from the University of Michigan Prostate Cancer Genetics Project (UM-PCGP). Descriptive information about the cases is presented in Table 1. The average age of PCa diagnosis in these 931 cases was 49.7 years. Approximately 62% (576/931) of the cases had a reported first or second degree relative with PCa. All UM-PCGP subjects provided written informed consent to participate in the study. The protocol and consent documents were approved by Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan Medical School.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 931 UM-PCGP early-onset PCa casesa.

| Clinical Trait | Mean (Standard Deviation) | Median (Range) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis (years) | 49.7 (4.1) | 50 (27-55) |

| Prediagnostic PSA (mg/dL)b | 20.6 (199.5) | 5.2 (0.4-5428) |

| Gleason Score | Nc | % |

| ≤ 6 | 410 | 44.6 |

| 7 | 427 | 46.4 |

| ≥ 8 | 83 | 9.0 |

| T Stage | Nd | % |

| T1 | 1 | 0.1 |

| T2 | 660 | 82.1 |

| T3 | 140 | 17.4 |

| T4 | 3 | 0.4 |

Includes 20 metastatic cases and 32 cases with lymph node involvement.

Prediagnostic PSA available on 870 cases.

Gleason scores available on 920 cases. Note: Prostatectomy Gleason used when available (n = 787), otherwise biopsy Gleason scores used (n = 133).

T Stage available on 804 cases.

Publically available unrelated male controls with GWAS variant data were selected from Illumina’s iControlDB database (n = 1126) (26). Controls were selected to have European reported ancestry and genotype data generated from a GWAS commercial platform similar to the platform used in UM-PCGP cases. Limited descriptive information, including age, gender and ancestry, on selected iControlDB subjects can be obtained from the Illumina website. Illumina iControls have not been screened for PCa.

Genotyping

Nine-hundred-thirty-eight European American UM-PCGP early-onset PCa cases were genotyped at Wake Forest University using the Illumina HumanHap 660W-Quad v1.1 BeadChip. The iControlsDB subjects were genotyped previously using the Illumina HumanHap550v1 or HumanHap550v3 commercial genotyping platforms.

Statistical Analyses

Initial genotyping quality control (QC) methodology was uniformly applied to all GWAS variants and samples (see Lange et al. (21) for details). Subjects missing >5% of variant genotyping calls across all GWAS variants were excluded from consideration. European ancestry for all subjects, including controls, was verified using the software ADMIXTURE (27); subjects with apparent misidentified ancestry or mixed ancestry were also removed from the study. Principal component analysis was also performed using the software Eigenstrat (28) on the combined sample of cases and controls using a linkage-disequilibrium (LD) pruned set of GWAS variants common across genotyping platforms for UM-PCGP cases and Illumina iControls.

We performed genotype imputation on the combined case-control sample to obtain genotype data on the 63 variants reported to be associated with PCa in Eeles et al. (20) and Goh et al. (29) using the software package MaCH (30,31). Genotype imputation was performed, separately, including variants from HapMap Phase II (CEU reference samples), HapMap Phase III (CEU + TSI reference samples) and the 1000 Genomes Project (Chromosome X only using all reference samples). For the autosomal variants, preference was given to Phase III imputation results when a variant was successfully imputed using both Phase II and Phase III HapMap samples. To reduce any possible bias in imputed genotype assignments due to different coverage of variants in the case and control participants, only variants that were successfully genotyped in >98% of both the cases and controls were included in the target panel prior to genotype imputation.

Logistic regression models, implemented in Mach2dat (31), were constructed to test the association between early-onset PCa and each of the 23 newly reported PCa variants using entirely imputed genotype data, scored as dosage values (expected number of copies of the minor alleles). The logistic regression models included covariate adjustment for the first 10 principal components derived from the GWAS data. A Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold for a one-sided test (one-sided p<0.0022), with requirement the direction of effect was consistent with the previous report, was applied to maintain an overall type I error rate of 0.05.

To assess the cumulative burden of the 23 recently identified variants on early-onset PCa, we estimated the total number of risk alleles each subject carries. The risk allele for each variant was defined as the allele associated with increased risk of PCa in Eeles et al. (20). For each subject, we calculated two risk scores, one based on the unweighted sum of risk alleles and the other based on a weighted sum, with the weight given to each variant risk allele equal to the natural logarithm of the corresponding variant’s reported odds ratio. For all variants, we used imputed genotype data, even if the variant was directly genotyped, to minimize the impact of any missing data on risk allele counts. We assessed, using t-tests, whether the unweighted total number of risk alleles was associated with PCa. We repeated these analyses for 40 previously established PCa variants for populations of European descent summarized in Goh et al. (29) (see Supplementary Table 1 for variant identities and their respective imputation quality). The individual association results for these 40 variants in UM-PCGP subjects have been reported previously (21). Finally, we calculated weighted and unweighted totals of risk alleles across all 63 variants.

To assess the relative ability to correctly classify subjects (with respect to case-control status), we constructed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and calculated the corresponding area under the curves (AUC) for weighted and unweighted aggregate risk allele counts for the 23 new PCa variants, 40 established PCa variants and the set of 63 total PCa variants. We then focused on the tails of the weighted and unweighted risk-allele sum counts and ranked subjects with regard to total number risk alleles, independent of disease status.

We additionally hypothesized that there was a subset of men with relatively extreme values of total risk-allele burden that could have their disease more accurately predicted than men with total risk-allele counts in the middle of the corresponding total risk-allele count distribution. Specifically, we performed two separate categorizations of all subjects based on the distribution of total risk alleles in controls. In the first categorization, subjects were assigned to a decile grouping based on their total risk allele count using cutoff values defined by the observed total-risk-score values in controls (e.g. the highest decile group would include cases and controls with observed total risk scores greater than 90% of the total risk scores observed in the controls). For each decile grouping, we calculated the odds ratios (ORs) comparing the proportions of cases and controls between the corresponding decile grouping and the lowest decile grouping (the reference group). In the other categorization scheme, we split cases and controls into two groupings defined by total-risk-allele threshold values across a range of percentiles cut-points (lower 2.5%, 5%, 10%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 90%, 95%, 97.5%) defined by the controls. For each percentile cut-point, we compared the distributions of cases and controls between the participant groupings defined by the percentile cut-point. These contingency-table-based analyses were performed using both weighted and unweighted risk-allele counts for the 23 new variants, 40 established variants and combined set of 63 variants.

Results

Ten out of 23 variants recently reported (20) achieved at least nominally significant evidence (one-sided p<0.05; direction of effect consistent with prior report) for association with early-onset PCa, including rs3771570 (p=0.032), rs7611694 (p=0.014), rs1270884 (p=0.0028), rs8008270 (0.025), rs7241993 (0.0023), rs2405942 (p=0.011), rs42445739 (p=3.0×10-5), rs3096702 (p=0.0018), rs2273669 (p=8.6×10-4) and rs1933488 (p=0.0011) (Table 2). The latter four variants were significantly associated with PCa after accounting for multiple testing (one-sided p<0.0022) (Table 2). Of the remaining 13 variants that did not minimally achieve nominal significance, only three (rs1894292, rs7141529 and rs11650494) had a direction of effect that was inconsistent with the discovery study.

Table 2.

Summary of findings for 23 newly reported PCa variants (20).

| Chr. | Position | Variant | A1/A2 | Freq. A2 Cases | R2 | OR (95% CI) Early-Onset PCaa | OR Eeles | p-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 153100807 | rs1218582 | A/G | 0.50 | 0.95 | 1.03 (0.90,1.17) | 1.06 | 0.34 |

| 1 | 202785465 | rs4245739 | A/C | 0.24 | 0.99 | 0.75 (0.65,0.86) | 0.91 | 3.0×10-5 |

| 2 | 10035319 | rs11902236 | G/A | 0.30 | 0.91 | 1.06 (0.92,1.22) | 1.07 | 0.22 |

| 2 | 242031537 | rs3771570 | G/A | 0.16 | 1.00 | 1.17 (0.99,1.39) | 1.12 | 0.032 |

| 3 | 114758314 | rs7611694 | A/C | 0.36 | 0.99 | 0.87 (0.77,0.98) | 0.91 | 0.014 |

| 4 | 74568022 | rs1894292 | G/A | 0.46 | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.89,1.15) | 0.91 | 0.57 |

| 5 | 172872032 | rs6869841 | G/A | 0.23 | 1.00 | 1.04 (0.89,1.21) | 1.07 | 0.31 |

| 6 | 32300309 | rs3096702 | G/A | 0.39 | 0.95 | 1.21 (1.06,1.37) | 1.07 | 0.0018 |

| 6 | 109391882 | rs2273669 | A/G | 0.17 | 1.00 | 1.32 (1.11,1.57) | 1.07 | 8.6×10-4 |

| 6 | 153482772 | rs1933488 | A/G | 0.41 | 1.00 | 0.83 (0.73,0.94) | 0.89 | 0.0011 |

| 7 | 20961016 | rs12155172 | G/A | 0.25 | 0.92 | 1.08 (0.93,1.21) | 1.11 | 0.15 |

| 8 | 25948059 | rs11135910 | G/A | 0.16 | 1.00 | 1.03 (0.86,1.22) | 1.11 | 0.37 |

| 10 | 104404211 | rs3850699 | A/G | 0.26 | 1.00 | 0.89 (0.78,1.02) | 0.91 | 0.056 |

| 11 | 101906871 | rs11568818 | A/G | 0.43 | 1.00 | 0.90 (0.80,1.03) | 0.91 | 0.058 |

| 12 | 113169954 | rs1270884 | G/A | 0.54 | 0.99 | 1.19 (1.05,1.35) | 1.07 | 0.0028 |

| 14 | 52442080 | rs8008270 | G/A | 0.17 | 1.00 | 0.85 (0.73,1.00) | 0.89 | 0.025 |

| 14 | 68196497 | rs7141529 | A/G | 0.51 | 1.00 | 0.92 (0.82,1.05) | 1.09 | 0.89 |

| 17 | 565715 | rs684232 | A/G | 0.38 | 0.99 | 1.06 (0.93,1.21) | 1.10 | 0.18 |

| 17 | 44700185 | rs11650494 | G/A | 0.09 | 0.97 | 0.87 (0.69,1.09) | 1.15 | 0.89 |

| 18 | 74874961 | rs7241993 | G/A | 0.26 | 0.91 | 0.81 (0.70,0.94) | 0.92 | 0.0023 |

| 20 | 60449006 | rs2427345 | G/A | 0.45 | 1.00 | 0.92 (0.80,1.04) | 0.94 | 0.091 |

| 20 | 61833007 | rs6062509 | A/C | 0.30 | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.85,1.11) | 0.89 | 0.32 |

| X | 9774135 | rs2405942 | A/G | 0.20 | 1.00 | 0.88 (0.78,0.98) | 0.88 | 0.011 |

Odd Ratios (OR) calculated with respect to allele 2 (A2).

One-sided p-value based on previous reported direction of effect (p<0.0022 significant after multiple test correction).

R2: Imputation Quality

Early-onset PCa cases had significantly more estimated total risk alleles than unscreened controls across these 23 variants (PCa cases: unweighted mean=21.61, se=0.10, median=21.70; controls: unweighted mean=20.69, se=0.09, median=20.55; p-diff = 2.0×10-12). Adding in the 40 established PCa variants, early-onset cases carried 58.02 (se=0.16, median=57.98) and controls carried 54.49 (se=0.15, median=54.64) risk alleles on average (p-diff=8.9×10-59) across all 63 variants. Overlapping histograms plotting the distributions of the unweighted and weighted sums of risk alleles for cases and controls across the 23 new PCa variants and 63 total PCa variants are presented in Supplementary Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

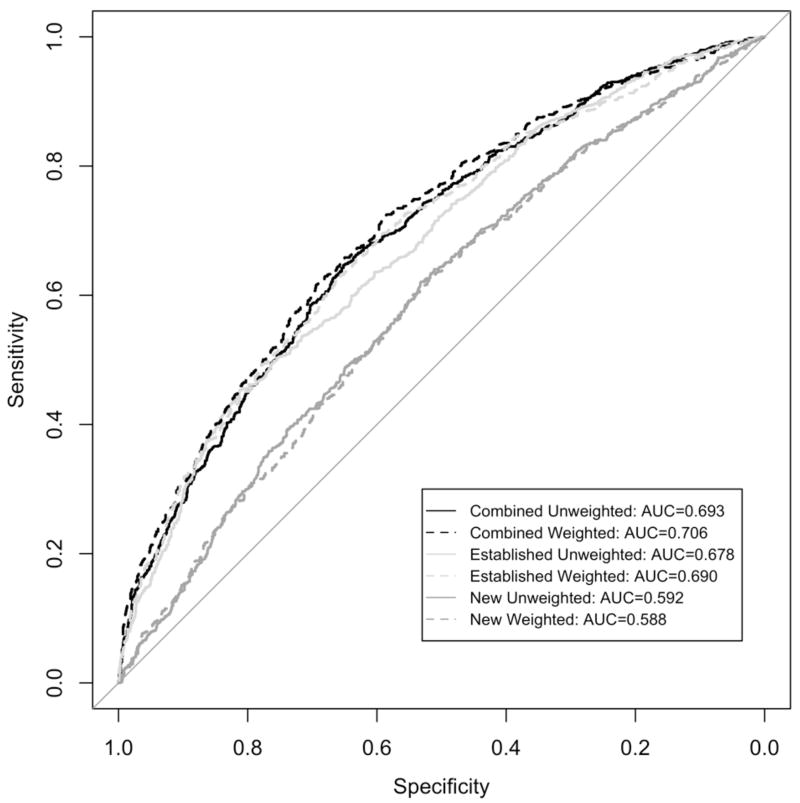

The aggregate burden of the risk alleles across the new variants alone provided a poor ability to discriminate between cases and controls (AUC=0.59 for both weighted and unweighted sums; Figure 1). The predictive value was only slightly higher when restricting the burden of risk alleles to the 10 new variants that demonstrated nominal evidence (p<0.05) of association in our study (AUC=0.61 for both weighted and unweighted sums). The ability to discriminate was noticeably better for the older established variants (AUC=0.69 for weighted sums, AUC=0.68 for unweighted sums). Adding the 23 new variants to the 40 established variants only modestly improved the ability to discriminate (AUC=0.71 for weighted sums, AUC=0.69 for unweighted sums) compared to the older variants by themselves.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curves, and corresponding area under curve (AUC), using weighted and unweighted burden of risk alleles for 23 new PCa variants, 40 established PCa variants and the 63 combined variants.

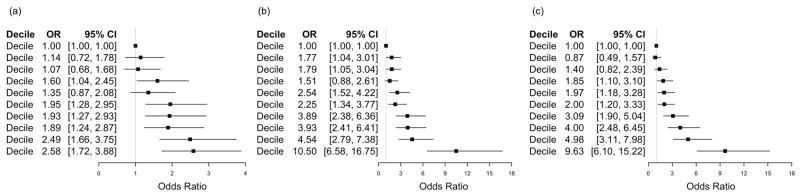

For all three sets of variants (new, established and combined) there was a steady increase, across decile categories, in the odds for men having PCa compared to the odds for men in the lowest decile grouping (Figure 2). For brevity, we focus here on results for the weighted total risk-allele scores (results were similar for unweighted scores (see Supplementary Figure 3)). A large jump in the odds ratios was observed between the highest decile group and the next highest decile group for the set of 40 established variants [OR = 10.50 (10th decile group) vs. 4.54 (9th decile group)] and combined set of 63 variants [OR = 9.63 vs. 4.98, respectively]) (Figure 2). The odds ratios across the decile groupings for the set of new variants were considerably less striking than for the other sets of variants and there was no large jump in the last decile grouping [OR = 2.58 for the 10th decile group vs. OR = 2.49 for the 9th decile group]. Categorizing subjects into two groups, based on percentile cut-points of the total-risk-allele sums in controls, revealed that the strongest odds ratios were observed for both the upper and lower extreme 2.5% tail cut-points of the total-risk-score distribution (see Supplementary Figure 4), consistent with the observed deficits of cases in the extreme lower tail and deficits of controls in the extreme upper tail of the total risk allele distributions.

Figure 2.

Association between decile categories (lowest decile group is reference category) for weighted number of risk alleles carried and PCa. Decile-specific odds ratios were estimated based on the imputed dataset (931 cases and 1,126 controls) for (a) 23 newly reported PCa variants (b) 40 established PCa variants (c) 63 combined PCa variants.

Discussion

More than 60 independent common PCa variants have been discovered through GWAS in men of European ancestry. The initial discoveries, often made with relatively small case-control samples, were made possible by the relatively strong effects (OR >1.25) of the associated variants. The more recent discoveries, including the 23 newly reported variants in Eeles et al. (20), required considerably larger sample sizes due to the associated variants having much smaller effects (OR~1.10). We have previously demonstrated that many of the older, stronger-effect, PCa variants are individually associated with early-onset PCa (21). Herein, we sought to assess whether there was evidence of association between early-onset PCa and these 23 new variants. We also evaluated the added utility of including the total burden of PCa risk alleles for these 23 new variants in combination with 40 previously established PCa variants on early-onset disease prediction. We note that we found no evidence supporting an association between the cumulative burden of PCa risk alleles and measures of disease severity including Gleason grade, tumor stage or PSA (data not shown).

We found at least nominal evidence (one-sided p<0.05; effect direction the same as the original study) supporting the reported associations for 10 of the 23 newly reported variants, including four that reached the conservative Bonferroni significance threshold. Ten of the 13 remaining variants had directions of effect consistent with the discovery report. Thus, despite relatively low power to detect such replication (for example, using a one-sided p=0.05, we had power = 0.38 to detect an associated variant with minor allele frequency = 0.25 and an OR = 1.10), we were able to provide supportive evidence that many of these variants are associated with early-onset PCa. A recent study that compared 312 hereditary PCa cases and 620 sporadic PCa cases to 587 common controls across these 23 variants found nominal evidence for association between PCa and eight of the variants for hereditary PCa (17/23 variants had consistent directions of effect with discovery study) and five of the variants for sporadic PCa (18/23 variants had consistent directions of effect) (25). No single variant achieved statistical significance after accounting for multiple testing in this study. Future larger replication studies are necessary to further validate each of these variants as a PCa risk variant.

The aggregate burden of risk alleles for the 23 new variants is strongly associated with early-onset PCa, but their cumulative predictive value is relatively poor. Not surprisingly, given their smaller number and smaller effect sizes, their overall predictive value is considerably smaller than was observed for the 40 established variants. Including the burden of these 23 variants to the burden of the 40 more established variants resulted in modestly stronger discrimination, with the greatest additional gains observed in men with extreme values of total risk-allele burden. These results suggest finding and including additional lower-effect common variants could be beneficial in disease prediction, but their added value will likely be small.

Three previous studies have evaluated the predictive value of the cumulative burden of established common risk alleles for PCa diagnosis (25,32,33). The recent report by Cremers et al. (25) described the cumulative risk for 74 PCa variants, including the same variant or a strong LD proxy for 39/40 of our established variants and all 23 new variants, separately in 312 Dutch hereditary PCa cases (mean age diagnosis 62 years) and 620 sporadic PCa cases (mean age diagnosis 65 years) compared to 587 common controls. Using an unweighted total risk allele score, Cremers et al. reported that the discriminative value based on these 74 variants was stronger for the hereditary PCa cases [AUC=0.73] than for the sporadic PCa cases [AUC=0.64]. The two earlier studies limited their analyses to established variants that demonstrated evidence for association in their own cohorts, whereas our study and the study by Cremers et al. included all previously reported associated variants regardless of evidence in our own studies. In Lindstrom et al. (32), 23/25 variants included in their risk calculations were included or had a strong LD proxy among our 40 established variants. Lindstrom et al. showed that the predictive value of the burden of common established risk alleles was stronger for men diagnosed with PCa earlier in life [e.g. AUC = 0.66 using men diagnosed age 60 years and younger compared to AUC = 0.60 in men diagnosed after the age of 75 years]. Agalliu et al. (33) identified 17/31 established variants that demonstrated at least nominal evidence for significance in a cohort of 979 PCa cases and 1,251 controls of Ashkenazic descent that were subsequently included in the construction of an unweighted total risk score (12/17 variants were included among our 40 established variants). The overall discriminative value of these 17 variants [AUC=0.64] was similar to the overall value observed by Lindstrom et al. [average AUC=0.63 across all ages for the 25 variants included in their study]. Consistent with Lindstrom, Agalliu et al. also observed a stronger association between total risk allele burden and PCa in younger cases. When comparing all men in the upper 25% of the total risk allele distribution to men in the lower 25%, Agalliu et al. found higher odds ratios in the younger men (diagnosed at age 60 years or younger; n=238) with PCa (OR = 5.20; 95% CI: (2.94,9.19)) than in the men diagnosed with PCa after age 60 years (OR = 3.30; 95% CI: (2.32, 4.68)).

One very interesting feature of the distribution of total risk alleles is the lack of evidence for a bi-modal distribution among cases and a noticeable deficit of cases in the lower tail of the total risk allele distribution (see Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). The shapes of the distributions of total risk alleles in cases looked very similar to those of controls, with the distribution for the cases shifted to the right. This observation would suggest that the burden of common risk-alleles plays an important role in the probability of developing disease irrespective of other risk factors (e.g. rare variants, environmental factors, epigenetic factors). A widely held hypothesis is that yet to be discovered uncommon high-penetrant risk alleles explain a significant proportion of the increased genetic susceptibility in PCa families and men with early-onset disease. This hypothesis is supported by our recent discovery of such a mutation, G84E, in HOXB13, which has a considerably higher frequency in men with early-onset and/or familial disease (34). It has been reported that a high burden of established common variants increases disease risk even among HOXB13 G84E carriers (35). Consistent with this report, among 23 UM-PCGP PCa HOXB13 G84E carriers in our study, the mean cumulative number of risk alleles across all 63 variants was 59.10 (sd=4.88) compared to 57.99 (sd=4.92) in non-G84E-carriers.

Disease misclassification in cases and/or controls can create biased estimates of effect. We note all cases in our study were confirmed by pathology report. Our controls were largely young males (average age 20 years) who have not, to our knowledge, been screened for PCa. While approximately 15% of these men will develop PCa some time in their lives, based on the age distribution of our cases and National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program PCa prevalence rates (36), we would expect a disease misclassification rate of ~0.7% (n~8/1126 of our controls) using our unscreened controls compared to a perfectly-diagnosed age-matched control sample for our early-onset PCa case sample. To assess the impact of this misclassification, we recalculated the mean number of total risk alleles in our iControls using this misclassification rate and the observed risk allele counts in our cases to get an unbiased maximum-likelihood-based estimate (MLE) of mean total risk alleles in our control sample. Using the MLE-based estimates would decrease the parameter estimates for mean number of total risk alleles from 20.69 (using the uncorrected-sample mean) to 20.68 (MLE-based mean) for the 20 new variants, 33.80 to 33.79 for the 43 established variants, and 54.49 to 54.47 for the combined set of variants. Thus, any bias using these unscreened young controls, relative to age-matched controls, is expected to be small and result in slightly conservative conclusions. Further, we note that our expected rate of disease misclassification in our controls is likely lower than that for most PCa case-control studies of older men that rely on PSA and digital rectal exam (DRE) screening. There is considerable overlap in distributions of PSA for men with and without PCa (37) and DRE screening misses Stage T1 PCa and PCa that does not occur peripherally in the posterior and lateral aspects of the prostate gland.

Our study includes several other features worthy of discussion. First, the iControls do not have available PCa family history and thus we cannot assess the additive value of PCa risk variants in conjunction with family history. Second, cases and controls were genotyped at separate times on separate, but similar, genotyping platforms. As we reported previously looking at >450,000 genotyped variants, we saw no evidence for systematic inflation of test statistics when comparing these cases to these controls (21). Still, it is possible that a small number of individual variants could be influenced by small genotype batch effects – though the direction of those batch effects would equally likely make our results conservative or anti-conservative, as the determination of the “risk allele” for each variant was based on independent data from previous reports. Third, we used imputed genotype data rather than directly genotyped data for analyses. Not all risk variants were directly genotyped and, when constructing burden scores for genotyped variants, missing data would cause unnecessary variation. We included only variants with high genotyping rates in both cases and controls in the target panel prior to genotype imputation and note that imputation quality was estimated to be excellent (R2>0.9) (see Table 1 and Lange et al.(21)) for the vast majority of variants. Fourth, a subset of patients (n=127) were directly ascertained for inclusion in linkage studies based on having known living relatives with disease and many other cases were symptomatic and identified in a hospital-based setting. Thus, this collection of 931 cases is likely not representative of early-onset PCa cases identified through standard epidemiological screening studies. Fifth, using previously reported ORs from studies based primarily on older men with disease, we demonstrate a small improvement in disease prediction using weighted total risk-allele counts compared to unweighted total risk-allele counts. Prediction of early-onset disease could be improved further by applying variant weights based specifically on studies of early-onset disease. We note that using weights based on our own individual variant effect estimates in an aggregate variant burden setting would be anti-conservative. Appropriate variant weighting for early-onset PCa aggregate risk-allele testing will need to be continuously refined as additional PCa populations are studied and new PCa variants are identified.

In summary, we provide the first significant evidence to support the association of several recently identified PCa variants to early-onset PCa. We establish that a high-burden of common risk alleles is strongly associated with early-onset PCa and that men with an aggregate burden of risk alleles in the tails of the total risk allele distribution have either high (men in the upper tail) or low (lower tail) odds of having early-onset PCa. Given the strong odds ratios observed in the upper tail, men with an unusually high number of risk alleles should be considered candidates for earlier PCa screening. The ability to discriminate between case-control status was largely driven by older established variants; including the 23 new variants only modestly improved disease prediction. Despite odds ratios that were considerably elevated there still remained considerable overlap between the case and control total risk allele distributions. Given this overlap and the apparent diminishing discriminating value of including newly discovered lower penetrant common variants, expanding the search for uncommon high-penetrant risk variants could be especially critical to further improving our ability to accurately predict men who will get early-onset disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the men with PCa who participated in this research project. We especially appreciate the support of Dr. Joel Nelson and his patients. The authors also express gratitude to Ms. Linda Okoth for assisting with UM-PCGP sample preparations and clinical data collection.

Financial Support: This work was primarily supported by NIH R01- CA136621 (E. M. Lange, K. A. Zuhlke, A. M. Johnson, J. Li, Y. Wang, J. Xu, S. L. Zheng, K. A. Cooney). Additional financial support provided by NIH P50-CA69568 (K. A. Zuhlke, A. M. Johnson, K. A. Cooney), NIH R01-HG006292 (Q. Duan, Y. Li) and NIH R01-HG006703 (E. M. Lange, Y. Wang, Q. Duan, Y. Li). J. V. Ribado was supported by the Post-Baccalaureate Research Education Program, NIH 5R25-GM089569.

Footnotes

The authors state no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bratt O, Damber JE, Emanuelsson M, Gronberg H. Hereditary prostate cancer: clinical characteristics and survival. J Urol. 2002;167:2423–2426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin DW, Porter M, Montgomery B. Treatment and survival outcomes in young men diagnosed with prostate cancer: a Population-based Cohort Study. Cancer. 2009;115:2863–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salinas CA, Tsodikov A, Ishak-Howard M, Cooney KA. Prostate cancer in young men: an important entity. Nat Rev Urol. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.91. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeegers MP, Jellema A, Ostrer H. Empiric risk of prostate carcinoma for relatives of patients with prostate carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2003;97:1894–1903. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amundadottir LT, Sulem P, Gudmundsson J, Helgason A, Baker A, Agnarsson BA, et al. A common variant associated with prostate cancer in European and African populations. Nat Genet. 2006;38:652–58. doi: 10.1038/ng1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freedman ML, Haiman CA, Patterson N, McDonald GJ, Tandon A, Waliszewska A, et al. Admixture mapping identifies 8q24 as a prostate cancer risk locus in African-American men. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14068–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605832103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duggan D, Zheng SL, Knowlton M, Benitez D, Dimitrov L, Wiklund F, et al. Two genome-wide association studies of aggressive prostate cancer implicate putative prostate tumor suppressor gene DAB2IP. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1836–44. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Manolescu A, Amundadottir LT, Gudbjartsson D, Helgason A, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a second prostate cancer susceptibility variant at 8q24. Nat Genet. 2007;39:631–37. doi: 10.1038/ng1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Steinthorsdottir V, Bergthorsson JT, Thorleifsson G, Manolescu A, et al. Two variants on chromosome 17 confer prostate cancer risk, and the one in TCF2 protects against type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:977–83. doi: 10.1038/ng2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeager M, Orr N, Hayes RB, Jacobs KB, Kraft P, Wacholder S, et al. Genome-wide association study of prostate cancer identifies a second risk locus at 8q24. Nat Genet. 2007;39:645–49. doi: 10.1038/ng2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eeles RA, Kote-Jarai Z, Giles GG, Olama AA, Guy M, Jugurnauth SK, et al. Multiple newly identified loci associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2008;40:316–21. doi: 10.1038/ng.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Rafnar T, Bergthorsson JT, Manolescu A, Gudbjartsson D, et al. Common sequence variants on 2p15 and Xp11.22 confer susceptibility to prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40:281–83. doi: 10.1038/ng.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas G, Jacobs KB, Yeager M, Kraft P, Wacholder S, Orr N, et al. Multiple loci identified in a genome-wide association study of prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40:310–15. doi: 10.1038/ng.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Olama AA, Kote-Jarai Z, Giles GG, Guy M, Morrison J, Severi G, et al. Multiple loci on 8q24 associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1058–60. doi: 10.1038/ng.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eeles RA, Kote-Jarai Z, Al Olama AA, Giles GG, Guy M, Severi G, et al. Identification of seven new prostate cancer susceptibility loci through a genome-wide association study. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1116–21. doi: 10.1038/ng.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Gudbjartsson DF, Blondal T, Gylfason A, Agnarsson BA, et al. Genome-wide association and replication studies identify four variants associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1122–26. doi: 10.1038/ng.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kote-Jarai Z, Olama AA, Giles GG, Severi G, Schleutker J, Weischer M, et al. Seven prostate cancer susceptibility loci identified by a multi-stage genome-wide association study. Nat Genet. 2011;43:785–91. doi: 10.1038/ng.882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schumacher FR, Berndt SI, Siddiq A, Jacobs KB, Wang Z, Lindstrom S, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies new prostate cancer susceptibility loci. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:3867–75. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eeles RA, Olama AA, Benlloch S, Saunders EJ, Leongamornlert DA, Tymrakiewicz M, et al. Identification of 23 new prostate cancer susceptibility loci using the iCOGS custom genotyping array. Nat Genet. 2013;45:385–91. doi: 10.1038/ng.2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lange EM, Johnson AM, Wang Y, Zuhlke KA, Lu Y, Ribado JV, et al. Genome-wide association scan for variants associated with early-onset prostate cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lange EM, Salinas CA, Zuhlke KA, Ray AM, Wang Y, Lu Y, et al. Early onset prostate cancer has a significant genetic component. Prostate. 2012;72:147–56. doi: 10.1002/pros.21414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kote-Jarai Z, Easton DF, Stanford JL, Ostrander EA, Schleutker J, Ingles SA, et al. Multiple novel prostate cancer predisposition loci confirmed by an international study: the PRACTICAL Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2052–61. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin G, Lu L, Cooney KA, Ray AM, Zuhlke KA, Lange EM, et al. Validation of prostate cancer risk-related loci identified from genome-wide association studies using family-based association analysis: evidence from the International Consortium for Prostate Cancer Genetics (ICPCG) Hum Genet. 2012;131:1095–1103. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-1136-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cremers RG, Galesloot TE, Aben KK, van Oort IM, Vasen HF, Vermeulen SH, Kiemeney LA. Known susceptibility SNPs for sporadic prostate cancer show a similar association with “hereditary” prostate cancer. Prostate. 2015;75:474–83. doi: 10.1002/pros.22933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.http://www.illumina.com/science/icontroldb.ilmn

- 27.Alexander DH, Novembre J, Lange K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 2009;19:1655–64. doi: 10.1101/gr.094052.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–09. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goh CL, Schumacher FR, Easton D, Muir K, Henderson B, Kote-Jarai Z, et al. Genetic variants associated with predisposition to prostate cancer and potential clinical implications. J Internal Med. 2012;271:353–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Willer CJ, Sanna S, Abecasis GR. Genotype imputation. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:387–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y, Willer CJ, Ding J, Scheet P, Abecasis GR. MaCH: using sequence and genotype data to estimate haplotypes and unobserved genotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:816–34. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindstrom S, Schumacher FR, Cox D, Travis RC, Albanes D, Allen NE, et al. Common genetic variants in prostate cancer risk prediction—results from the NCI Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium (BPC3) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;2:1437–44. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agalliu I, Wang Z, Wang T, Dunn A, Parikh H, Myers T, et al. Characterization of SNPs associated with prostate cancer in men of Ashkenazic descent from the set of GWAS identified SNPs: impact of cancer family history and cumulative SNP risk prediction. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ewing CM, Ray AM, Lange EM, Zuhlke KA, Robbins CM, Tembe WD, et al. Germline mutations in HOXB13 are associated with prostate cancer risk. New Engl J Med. 2012;366:141–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karlsson R, Aly M, Clements M, Zheng L, Adolfsson J, Xu J, et al. A population-based assessment of germline HOXB13 G84E mutation and prostate cancer risk. Eur Urol. 2014;65:169–76. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson IM, Pauler DK, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Lucia MS, Parnes HL, et al. Prevalence of prostate cancer among men with a prostate-specific antigen level ≤4.0 ng per millileter. New Engl J Med. 2004;350:2239–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.