Abstract

This paper examines associations among parental and adolescent health behaviors and pathways to adulthood. Using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, we identify a set of latent classes describing pathways into adulthood and examine health-related predictors of these pathways. The identified pathways are consistent with prior research using other sources of data. Results also show that both adolescent and parental health behaviors differentiate pathways. Parental and adolescent smoking are associated with lowered probability of the higher education pathway and higher likelihood of the work and the work & family pathways (entry into the workforce soon after high school completion). Adolescent drinking is positively associated with the work pathway and the higher education pathway, but decreases the likelihood of the work & family pathway. Neither parental nor adolescent obesity are associated with any of the pathways to adulthood. When combined, parental/adolescent smoking and adolescent drinking are associated with displacement from the basic institutions of school, work, and family.

Keywords: adolescent health behaviors, parent health behaviors, transition to adulthood

A growing body of research reveals intragenerational health selection in which health during childhood affects socioeconomic achievements later in life (Case, Fertig, and Paxson 2005; Jackson 2009; Palloni 2006). For example, diverse indicators of poor health in childhood are negatively associated with educational attainment (Eide and Showalter 2011) and occupational standing and wealth (Palloni et al. 2009), with diminished income likely persisting into mid-adulthood (Haas, Glymour, and Berkman 2011). Later experiences in adolescence—including obesity, migraine headaches, poor mental health, and drinking—also predict educational attainment (Balsa, Giuliano, and French 2011; Crosnoe 2007; Currie et al., 2010; McLeod and Fettes 2007; Rees and Sabia 2011).

The present paper broadens this body of research and suggests new avenues for inquiry in two respects. First, research tends to emphasize singular aspects of socioeconomic attainment and rarely characterizes the sequence of successive roles and the multifaceted pathways to adulthood that include—in addition to educational attainment and paid work—family formation. As Macmillan and Copher (2005) note, although technically challenging to study, pathways richly describe movement into adulthood because they depict the timing of entry into each role (i.e., trajectories) and configurations of these trajectories (i.e., pathways) in a unified manner. Such an approach allows for the study of an often-stated but rarely-studied dictum: the significance of any particular role (e.g., student, paid worker) depends on other role involvements and their timing (e.g., early versus late parenthood) (Marini 1985, 1987; Marini, Shin, and Raymond 1989; Miech et al. 2015; Moen 2003; Mouw 2005). The preponderance of extant evidence focuses on youth health behaviors and their implications for educational attainment and income. Less is known about adolescent health behaviors and family formation, or about how health behaviors may influence combinations of marriage and parenthood with student and worker roles.

Second, the paper proposes and tests a model of inter- and intragenerational health selection according to which health behaviors of parents and adolescents shape the multidimensional pathways that people follow into adulthood. Previous research shows that adults whose parents reported poor physical health during adolescence are significantly less likely to attain a college degree (Boardman et al. 2012) but this work did not specifically evaluate behavioral pathways through which this association may have operated. The present paper joins findings from life course sociology and behavioral medicine to articulate hypotheses about parental health behaviors and their implications for pathways to adulthood.

To be sure, numerous studies have examined parental and adolescent health precursors to specific aspects of pathways to adulthood (particularly education; e.g., Case et al. 2005; Jackson 2009). In addition, some studies have examined the effects of adolescent health behaviors on pathways to adulthood (particularly substance use; e.g., Oesterle, Hawkins, and Hill 2011). But none of this work has simultaneously considered parental and adolescent health behaviors, modeled pathways with current latent class modeling techniques, or drawn on nationally representative data. This study adds to this existing research using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) and latent class models to (1) identify and characterize different pathways to adulthood among a nationally representative sample of young adults and (2) examine whether an array of adolescent and parental health behaviors are associated with these pathways.

PATHWAYS TO ADULTHOOD

Life course scholars typically recognize five transition markers that distinguish different pathways to adulthood: completing one’s education, obtaining full-time employment, setting up an independent household, getting married, and having children (Rindfuss, Swicegood, and Rosenfeld 1987). The different possible combinations and timings of these transitions define different pathways and can have significant long-term social ramifications (Hogan 1978; Marini et al. 1989). Studies of the transition to adulthood have emphasized a process of deinstitutionalization whereby a small number of culturally normative combinations and timings of transitions have given way to a much more heterogeneous set of transition patterns (Shanahan 2000). Nonetheless, recent research has identified a relatively parsimonious set of ideal typical pathways in the contemporary United States.

One pathway reflects a delayed transition to adulthood (Amato et al. 2008; Amato and Kane 2011; Osgood et al. 2005). This pathway comprises young adults who do not seek postsecondary education, may have difficulty establishing themselves in a full-time job with the prospects of a long-term career, may continue to live with their parents, and generally have limited family formation. Other common pathways are distinguished along two axes: the decision or opportunity to pursue higher education and the decision or opportunity to delay family formation (Amato et al. 2008; Amato and Kane 2011; Oesterle et al. 2010, 2011; Osgood et al. 2005; Sandefur, Eggerling-Boeck, and Park 2005). Using data on 728 respondents from the Seattle Social Development Project, Oesterle et al. (2010), for instance, distinguish pathways involving postsecondary education with limited family formation from pathways involving family formation with limited education beyond a high school degree for both men and women. Similarly, using data from the Michigan Study of Adolescent Transitions for almost 1,500 young adults, Osgood et al. (2005) distinguished pathways involving a focus on marriage and family (“fast starters”), pathways focusing on career and postsecondary education (“educated singles”), and pathways combining postsecondary education and family formation (“educated partners”). While this work is critical to life course research on pathways to adulthood, it has largely relied upon relatively small, regionally specific samples. Thus, Goal 1 of our paper is to identify and characterize pathways to adulthood in a nationally representative sample of recent cohorts.

HEALTH BEHAVIORS AND PATHWAYS TO ADULTHOOD

Health behaviors may be associated with pathways to adulthood because they have the potential to durably influence a young person’s emotional, cognitive, and social capital. In turn, these sources of capital affect young people’s capacities to succeed in the educational, labor, and marriage markets. Indeed, children and adolescents exposed to detrimental parental health behaviors—and especially those who also adopt detrimental health behaviors themselves—may have diminished cognitive, emotional, and social capacities that then constrain opportunities to pursue pathways to adulthood involving higher education and/or family formation.

Parent Health Behaviors

Parents influence the pathways to adulthood of their children because they help shape adolescent health behaviors both genetically and via social learning processes. There is abundant evidence that poor parental health behaviors are associated with social learning processes that increase the likelihood of similar poor health behaviors among their children, including poor diets and eating patterns that may lead to obesity (Kral and Rauh 2010), inactivity (Richards et al. 2009), and smoking and drinking (Göhlmann, Schmidt, and Tauchmann 2010; Hussong et al. 2008; Kandel and Wu 1995). That is, smoking, obesity, and drinking “transmit” from parents to their children. The potential for social learning processes and genetic propensities suggests that parental health behaviors are distal to pathways to adulthood, in contrast to adolescent health behaviors. According to this perspective, parent health behaviors will not explain pathways beyond the effects of adolescent health behaviors.

Alternatively, parental health behaviors could play a significant role if they affect child development at a critical or sensitive stage in early life. For example, parental substance use may influence social, emotional, and cognitive skills independent of the adolescent’s own substance use and/or subsequent experiences. To date, there is no existing research on the way in which parental health behaviors predict the pathways to adulthood of their children. Goal 2 is thus to examine whether these parental health behaviors, above and beyond adolescent health behaviors, are associated with transition patterns to adulthood.

What parental health behaviors may be predictive of their children’s pathway to adulthood? There is a growing body of increasingly sophisticated research showing that parent substance use, both during pregnancy and throughout childhood and early adolescence, can durably alter their children’s emotional, social, and cognitive capacities, raising the possibility of intergenerational health effects on pathways. Parental tobacco and alcohol use have been studied extensively and their developmental consequences may have implications for transition patterns. Specifically, smoking in the household is associated with children’s emotional development, including increased risk of externalizing symptoms and disorders (aggression, criminality), depression, and, most consistently, ADHD (Cornelius and Day 2009; Pauly and Slotkin 2008). Parental smoking and alcohol use, particularly during pregnancy, have been associated with disruptive behavioral disorders—oppositional defiance, conduct disorder, ADHD (Latimer et al. 2012)—and they are risk factors for other psychiatric disorders (Hill et al. 2000). Parental alcohol use has been associated with growth restriction, antisocial behaviors, internalizing problems (for girls), and academic difficulties among children and early adolescents (Hussong et al. 2008).

The relationships between parent substance use and child and adolescent psychosocial development likely reflect a combination of social and biological processes. Parent substance use can alter parenting practices. For instance, past studies have shown that alcoholic parents are less likely to discipline their children (King and Chassin 2004), and they are less likely to provide emotional support (Rutherford et al. 1998) and monitoring (van der Vorst et al. 2006). In turn, such children may lack self-regulator skills that help one to succeed in educational settings, workplaces, and interpersonal relationships.

Experimental designs with nonhuman animal studies confirm associations between smoking and emotional and cognitive development, and evidence is accumulating that documents biological mechanisms that could in part account for these relationships in humans (Bublitz and Stroud 2012; Maritz and Harding 2011). For example, a recent review concluded that second-hand smoke has notable associations with diminished neurological development, which may have implications for cognition and emotions. The combination of emotional, social, and cognitive difficulties associated with parental smoking and alcohol use suggests that youth exposed to these risk factors will be less likely to continue their educations to the tertiary level (which requires cognitive and social skills), and will be less likely to engage in family formation or higher status occupations (owing to diminished emotional and social skills, which lowers competitiveness in marriage and labor markets). That is, these risk factors will increase the likelihood of pathways involving limited involvements in higher education, family formation, and full-time jobs.

Adolescent Health Behaviors

Goal 3 of our analyses is to describe how adolescent health behaviors are associated with combinations of school, work, and family careers that characterize distinct pathways to adulthood. Below we highlight how health outcomes can theoretically cause changes in life course pathways.

BMI

Adolescent health behaviors may also have cognitive, emotional, and social consequences that, in turn, affect young people’s capacities to succeed in schools, workplaces, and marriage markets. Beginning with education, several studies have found that BMI has a negative association with educational attainment, particularly among women, which may reflect weight-based stigma and marginalization (Crosnoe 2007; Crosnoe and Muller 2004; Glass, Haas, and Reither 2010; von Hippel and Lynch 2014).

Beyond affecting educational attainment, adolescent health behaviors may also influence success in labor markets through similar processes. For instance, the stigma associated with being overweight carries over to the labor market with heavier people facing wage penalties and a lower likelihood of promotion to managerial positions (Conley and Glauber 2007; Glass et al. 2010). Speculatively, it may be that overweight youth are less likely to become employed among those youth who do not attend college.

Family formation is sometimes conceptualized as occurring in the context of a “marriage market” consisting of a supply of possible spouses with differing “values” (Becker 1981; Oppenheimer 1988). Assessments of value reflect many forms of capital thought to indicate earnings potential, fecundity, and the likelihood of high parental investments in children: social, human, and psychological capital but also indicators of physical health. Indeed, research consistently shows that health increases the likelihood of marriage (Goldman 1993; Harris 2010; Wade and Pevalin 2004). Body mass index (BMI) reliably predicts the probability of getting married and the timing of marriage, with larger effects observed among women (Averett and Korenman 1994; Averett, Sikora, and Argys 2008; Conley and Glauber 2007; Fu and Goldman 1996). Higher BMIs are also associated with adverse reproductive outcomes among females, reflecting a potentially large range of physiological mechanisms (Jungheim et al. 2012).

Substance Use

Adolescent substance use is also consistently found to have a negative association with educational attainment (e.g., King et al. 2006), an association that likely reflects reciprocal processes (Crosnoe 2006). Substance use may exert a negative effect on education by directly interfering with social and cognitive capacities that promote school success (Baumrind and Moselle 1985). It may also work through more indirect processes, as substance use is a “social Rubicon” that comes to define substance users, in terms of both self-appraisals and peer appraisals, as a member of an adolescent social group that eschews customary social norms and goals, including educational success (Kobus 2003).

Studies have also found that adolescent substance use is associated with unemployment and welfare receipt in young adulthood (Brook et al. 1999; Oesterle et al. 2010; Osgood et al. 2005). Substance use is also thought to lower “value” in marriage markets. Yamaguchi and Kandel (1985a) proposed that adolescent substance use is incompatible with family formation, a proposition supported by a considerable body of research with respect to illegal drugs and marijuana (Yamaguchi and Kandel 1985a, 1985b) and heavy episodic drinking (Duncan, Wilkerson, and England 2006; Staff et al. 2010; Waldron et al. 2008). Such findings are unsurprising given that many controlled substances disrupt interpersonal relationships, often lead to social withdrawal, and alter one’s nervous system in fundamental ways.

The foregoing considerations suggest that adolescent substance use and BMI are associated with individual aspects of transitions and indeed suggest potential, causal links in which these health outcomes lead to disengagement from the basic institutions of education, work, and family. This study is one of the first to examine how both parental and adolescent health may influence multifaceted pathways using a nationally representative sample. Further, the prospective research design allows us to establish temporal order between health and later life course pathways, an important criteria to help separate causal effects from spurious ones.

DATA AND METHODS

Data come from Waves I and IV of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health).1 Wave I of Add Health is a nationally representative sample of adolescents who were enrolled in middle school or high school in 1994. The sample was obtained by first randomly selecting 80 high schools from a list of all high schools in the United States stratified to ensure adequate representation of different regions, types of schools, ethnic compositions of schools, and study body sizes. The 80 high schools were then paired with 65 middles schools that fed into their student body. The combined 145 middle and high schools hosted an in-school survey that yielded 90,118 student respondents in grades 7 through 12 in 1994. Approximately 200 students from each school were randomly selected for in-depth in-home interviews, which resulted in a sample of 20,745 adolescents at Wave I. The in-home component also included an interview with a parent or caretaker (typically the mother or female head of the household if available). The parent/caretaker interviews included information about parent socioeconomic status and health behaviors that is used in the following analyses. A fourth wave of data was collected 14 years after Wave I. Of the eligible respondents from Wave I, 93% were re-located and 80% were re-interviewed, resulting in 15,701 adult in-home interviews.

At Wave IV, respondents ranged in age from 24 to 35. In order to focus on the years covering the transition to adulthood, the analysis is limited to respondents who were at least 30 years old when interviewed at Wave IV (N = 5,326). This filter maximizes sample size while ensuring that a sufficient period of time had elapsed after completing their education for respondents to settle into relationships and start families. The age range of this analysis, 18 to 30, is wider than has been considered in most studies of the pathways to adulthood (for an exception see Oesterle et al. 2010, 2011). An additional 227 respondents (4 percent) are excluded who did not have valid sample weights, which leaves an analysis sample of 5,099 respondents.

Percentages of missing data ranged from roughly 1 percent for respondent variables (including parent education) to roughly 20 percent for parent/caretaker variables. Missing data were addressed via multiple imputation in which twenty complete data sets, a number recommended to help ensure stable parameter and standard error estimates (Graham, Olchowski, and Gilreath 2007), were constructed using Stata’s implementation of multiple imputation with chained equations (StataCorp 2013). Diagnostic tests of the imputed data indicated that the values did not appreciably depart from the distributions of the variables in the original dataset (Eddings and Marchenko 2012).

Measures

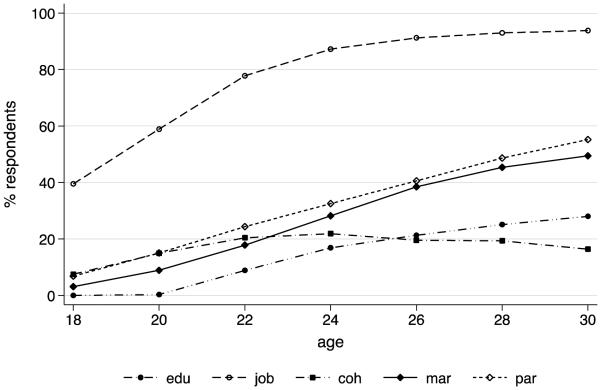

The primary markers of the transition to adulthood include completing one’s education, obtaining a full-time job, establishing an independent household, cohabiting or getting married, and having children. Add Health includes sufficient information to determine the age at which a respondent acquired, if at all, each of these adult roles with the exception of establishing an independent household. Information reported by the respondents at Wave IV was used to construct a person-age dataset in two-year age intervals with indicators for each adult role (see Figure 1).2

Figure 1. Percentage of respondents holding each adult role between the ages of 18 and 30 in two-year age intervals.

Edu = completed a four-year college degree or higher degree; job = obtained a full-time job; coh = cohabited; mar = married; par = had at least one child. Percentages are weighted using Add Health Waves I to IV sample weights.

First Full-time Job

At Wave IV respondents reported the age at which they first worked in a job for 35 or more hours per week. Ideally, it would be possible to determine the types of jobs respondents held in each given two-year age interval as this would allow for a better sense of employment trajectories in early adulthood as well the nature of the work (Mortimer 2003), but Add Health does not include such detailed employment histories. The percentage of respondents who had obtained a full-time job steadily increased from around 40 percent at age 18 to around 90 percent by age 24 and then leveled off around 95 percent by age 30.

Educational Attainment

At Wave IV respondents reported the year in which they obtained any post-secondary degree (associate’s, bachelor’s, or graduate). Given the importance of a four-year degree in the contemporary U.S. (Hout 2012), the education series is constructed around obtaining four-year college/university and higher degrees.3 For respondents with a four-year degree or higher, the education series indicators are set to 0 until the age they completed their highest degree and then set the indicators to 1 for all following ages. By age 30, 29 percent of respondents had obtained a four-year or higher degree.

Cohabitation and Marriage

Wave IV of Add Health captures detailed histories of the relationships of respondents. The data include the dates that each cohabiting or marital relationship began and ended. This information was used to determine for each 2-year age interval whether respondents were married, cohabiting, or neither. For respondents who held more than one role during a given 2-year age interval marriage is privileged over cohabitation and either marriage or cohabitation is privileged over neither. Percentages of cohabitation increase from under 10 percent at age 18 to around 20 percent by age 22. This percentage holds steady through the mid-20s and then falls to around 17 percent at age 30. For marriage, the percentage steadily increases from around 3 percent of respondents at age 18 to around 50 percent of respondents by age 30.

Parenthood

The date of birth of the respondent’s oldest child was used to determine the age at which the respondent first became a parent, if at all. The percentage of respondents who had at least one child steadily increased from around 5 percent at age 18 to 55 percent by age 30.

Adolescent Health Behaviors

The measures of adolescent health behaviors are drawn from the Wave I in-home interviews. Respondents were asked to report their height and weight, which were used to calculate their body mass index (BMI). BMI based on self-reported height and weight has been shown to be highly reliable (r = 0.92) using these same data (Goodman, Hinden, and Khandelwal 2000). Growth charts provided by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention were used to identify respondents who were above the 95th percentile for their age and sex, a threshold for being obese (Kuczmarski et al. 2002). Respondents also reported their frequency of drinking during the past 12 months (responses ranged from 0 “never” to 6 “nearly every day”) and whether or not they had ever smoked at least one cigarette per day for a period of 30 days (i.e., ever had a period of daily smoking). A little over 10 percent of the respondents were obese in adolescence, close to a third had ever smoked daily, and the average frequency of drinking fell between drinking 1 or 2 days in the past month and once a month (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Weighted means/proportions for parental health behaviors, adolescent health behaviors, and other covariates; N = 5099.

| Mean/Proportion | |

|---|---|

| Adolescent Health Behaviors | |

| Adolescent obese | 0.11 |

| Adolescent ever smoked daily | 0.30 |

| Adolescent drinking | 1.60 |

| Parental Health Behaviors | |

| Parent obese | 0.25 |

| Parent smokes | 0.28 |

| Parent drinking | 1.97 |

| Other Covariates | |

| Wave IV age | 30.62 |

| Female | 0.46 |

| Race: White | 0.63 |

| Race: Black | 0.18 |

| Race: Hispanic | 0.12 |

| Race: Other | 0.06 |

| Two biological parents | 0.51 |

| Parent education | 5.78 |

| Parent income (log) | 4.15 |

| Living environment | 6.68 |

| Adolescent GPA | 2.77 |

| Adolescent college aspirations | 4.26 |

Notes: Means/proportions are weighted using the Add Health Waves I to IV sample weights and are averaged across 20 complete data sets. Adolescent drinking ranges from 0 = never to 6 = nearly every day. Parental drinking ranges from 1 = never to 6 = nearly every day. Parent education ranges from 0 = less than 8th grade to 9 = some education beyond a four-year degree. Living environment ranges from 2 to 8 and is coded such that higher values indicate a better environment. Adolescent college aspirations range from 1 = low to 5 = high.

Parental Health Behaviors

The analysis draws on a number of measures of parental health behaviors taken from the parent/caretaker interview conducted at Wave I. The parent/caretaker reported whether or not s/he smoked at the time of the survey and his/her frequency of drinking over the last year (responses ranged from 1 “never” to 6 “nearly every day”). The parent/caretaker also reported whether or not the respondent’s biological mother and/or father was obese. Around 25 percent of respondents had an obese parent, close to 30 percent had a parent/caretaker who smoked, and parent/caretaker drinking averaged close to once a month (see Table 1). The polychoric correlations between parent and adolescent health behaviors range from .21 for frequency of drinking to .24 for smoking and .38 for obesity. These correlations suggest a modest to moderate degree of intergenerational transmission of health behaviors that is broadly consistent with findings from past studies (Chassin et al. 1998; Crossman, Sullivan, and Benin 2006; Kandel and Wu 1995; Wickrama et al. 1999).

Additional Covariates

Parental and adolescent health behaviors are known to be associated with socioeconomic resources, adolescent academic performance, and college aspirations, as is the likelihood of different paths to adulthood (Amato, Landale, Havasevich-Brooks, Booth, Eggebeen, Schoen, and McHale 2008; Oesterle, Hawkins, Hill, and Bailey 2010; Osgood, Ruth, Eccles, Jacobs, and Barber 2005; Sandefur, Eggerling-Boeck, and Park 2005). Socioeconomic resources as well as values that are partially encoded in measures such as college aspirations both provide opportunities and inform choices concerning different pathways to adulthood. Parent education (ranges from 0 “less than 8th grade” to 9 “some education beyond a four-year degree), log family income, condition of the living environment (the sum of interviewer ratings of the physical condition of the household and the neighborhood with high scores indicating better conditions), family structure (an indicator for whether the respondent lived with both biological parents), self-reported grade point average, and college aspirations (ranges from 1 “low” to 5 “high”) are included in the models as potential confounders. The models also adjust for sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white as the referent, non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, and other racial/ethnic groups) and age at Wave IV.

Statistical Models

Numerous studies of the transition to adulthood have drawn on latent class models to help identify different pathways people take (Amato et al. 2008; Janus 2009; Macmillan and Copher 2005; Macmillan and Eliason 2003; Oesterle et al. 2010, 2011; Osgood et al. 2005; Sandefur et al. 2005). Latent class models are particularly suitable for these analyses because they specify the relationships among a set of categorical observed variables (indicators of adopting adult roles) as dependent on an unobserved (latent) categorical variable that captures different pathways. This class of models also allows researchers to simultaneously estimate associations between covariates and latent class membership (i.e., membership on a given pathway) within a multinomial regression framework (Collins and Lanza 2010; Magidson and Vermunt 2001; Muthen 2001).

Following Collins and Lanza’s (2010) notation, the conditional latent class models are given by

| (1) |

| (2) |

where j = 1, …, 28 adult role measures, rj = 0, 1 response categories for the adult role measures (rj = 0, 1, 2 for the relationship measures), y is a vector of responses to the adult role measures, x is a vector of predictors of membership on a given pathway (latent class), γc(x) is the probability that the categorical latent variable L equals a given pathway (class) c conditional on x, I(.) is an indicator function that equals 1 when the response to adult role measure j equals rj, and ρj,rj|C is the item-response probability for role indicator j with response rj given membership in pathway c. In the second equation, β is a vector of parameter estimates giving the association between the covariates and membership in a given pathway. The conditional item-response probabilities allow one to characterize the pathways with respect to the probability of adopting each of the adult roles (Goal 1), the assignment of respondents to pathways based on the highest probability of class membership allows one to assess the distribution of pathways (Goal 1), and the estimates for β allow one to examine associations with membership in a given pathway (Goals 2 and 3).

Parameters for the conditional latent class models were estimated using Mplus 7.2 (Muthén and Muthén 2012). The parameter estimates were obtained from averaging over the 20 complete data sets. Mplus uses a maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors. Given the complexity of the model, 500 initial stage random starts and 10 final state optimizations were used to avoid local solutions. All models incorporate the Add Health Waves I to IV sample weights. All of the Stata and Mplus code for the analysis is available for replication and further analysis at the following github archive ([identifying web link omitted]).

One challenge with latent class models lies in determining the optimal number of classes. Various model fit statistics are available, but in many cases improvements in model fit continue to be detected as the number of classes increases. Furthermore, recent research suggests that focusing on a precise estimate of the number of classes can lead to misleading results (Warren et al. forthcoming). This study relies on the following strategy for the analysis. First, models are estimated allowing for between 2 and 7 pathways. Second, the log likelihood and the BIC are assessed to identify either a minimum or an inflection point where further improvements are relatively small. Third, the Lo-Mendell-Rubin test statistic is assessed (Lo, Mendell, and Rubin 2001; Nylund and Masyn 2008). The Lo-Mendell-Rubin test statistic, however, is invalid when using multiply imputed data. Therefore, the test statistic is obtained for unconditional latent class models that do not include covariates and thus do not have missing data. The distributions and characterizations of pathways that emerge from the unconditional latent class models are very similar to those that emerge with the conditional latent class models, which suggests that the Lo-Mendell-Rubin test statistic for the unconditional latent class models should be informative for the conditional latent class models. Fourth, a measure of entropy that provides a summary of the degree of uncertainty in the classification of respondents to classes is considered. Finally, the interpretability of the pathways that emerge is considered. To reflect the uncertainty regarding the optimal number of pathways results are reported for the two best-fitting models.

RESULTS

Pathways to Adulthood

Goal 1 is to identify the pathways to adulthood that emerge among the Add Health respondents. Table 2 reports the fit statistics for models allowing between 2 and 7 pathways (classes). The log-likelihood and the BIC continue to improve (i.e., become smaller) through models allowing for seven pathways, but there is an inflection point at 5 pathways where improvements in the BIC trail off at 3 percent. The Lo-Mendell-Rubin test statistic indicates that the model allowing for 5 pathways is not a significant improvement over the model allowing for 4 pathways and thus supports the 4-pathway model. The measure of entropy indicates that both the models allowing for 4 and 5 pathways do an excellent job of classifying respondents into the pathways. Based on the combination of the BIC and the Lo-Mendell-Ruben test statistic, the analysis proceeds with the models allowing 4 and 5 pathways.

Table 2.

Model fit statistics for models allowing for 2 to 7 pathways.

| # pathways |

LL | BIC | % reduction in BIC |

LMR p-value |

Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | −66800 | 134352 | 61% | 0.000 | 0.96 |

| 3 | −59888 | 120979 | 10% | 0.000 | 0.98 |

| 4 | −56201 | 114058 | 6% | 0.000 | 0.98 |

| 5 | −54133 | 110376 | 3% | 0.182 | 0.98 |

| 6 | −52305 | 107171 | 3% | 0.098 | 0.97 |

| 7 | −50374 | 103761 | 3% | 0.037 | 0.97 |

Notes: The percent reduction in BIC is based on the model allowing one fewer class. The LMR p-value refers to the p-value from the Lo-Mendell-Rubin test statistic from the unconditional latent class model. The test statistic concerns whether the model with a given number of classes has a significantly better fit with the data than the model with one fewer class.

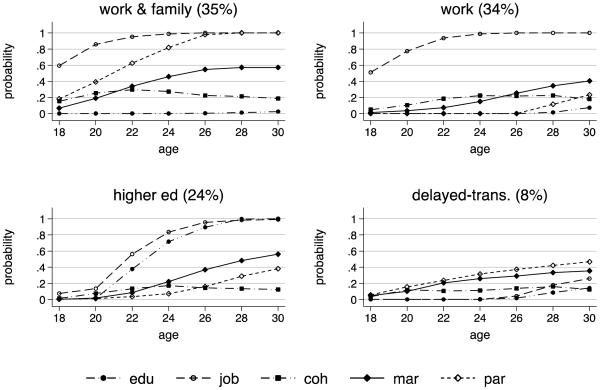

Figure 2 provides a characterization of the pathways that emerge in the models allowing 4 pathways. The subpanels portray the item response probabilities conditional on membership in a given latent pathway for each two-year age interval. For this analysis the item response probabilities capture the estimated probability of occupying a given adult role for each pathway and thus allow one to describe and interpret the pathways. The percentage of respondents associated with each pathway based on having the highest probability of membership in the given pathway is noted in parentheses. Consistent with the high entropy measures, the average classification probabilities for the most likely pathway membership among the respondents are all quite high (i.e., above 0.95).

Figure 2. Characterization of pathways based on conditional item response probabilities for the 4-pathway model.

Edu = completed a four-year college degree or higher degree; job = obtained a full-time job; coh = cohabited; mar = married; par = had at least one child. Percentage of respondents with the given pathway as the most likely pathway in parentheses.

Beginning with the 4-pathway model (Figure 2), the first pathway is characterized by a relatively high probability of obtaining a full-time job by ages 18 and 20 (around .6 at age 18 and over .8 by age 20), a steadily increasing probability of having a child in the early 20s (around .2 at age 18 and increasing to .8 by age 24), and a moderate probability of marriage and/or cohabitation in the early 20s (around .2 for both at age 20 and around .4 for marriage and .3 for cohabitation by age 24). In the later 20s the probability of marriage stabilizes around .6 while the probability of cohabitation drops to around .2. This pathway is also characterized by a near 0 probability of completing a four-year college degree or higher degree. We refer to this pathway as the work & family pathway and it is the best fit for 35 percent of the respondents. (The labels are meant only to simplify discussion of the results and are not intended to capture the full complexity of the groups.)

The second pathway that emerges has a slightly delayed trajectory of work and a much lower likelihood of family formation relative to the work & family pathway. This pathway is characterized again by a relatively high probability of finding a full-time job in the early 20s (around .5 at age 18 rising to over .9 by age 22), but relatively low probabilities of all other adult roles. The probability of being married begins to increase at age 22 and reaches .4 by age 30. The probability of cohabitation remains steady at around .2 from ages 22 to 30. This pathway is also characterized by a low probability of having a child (.2 by age 30) and also a near 0 probability of completing a four-year college degree or higher. We refer to this pathway as the work pathway and it is the best fit for 34 percent of the respondents.

The third pathway that emerges is quite distinct from the previous two. This pathway is characterized by a delayed entry into full-time work and an investment in higher education. The probability of completing a four-year or higher degree increases from around .4 at age 22 to around .9 by age 26. Similarly, the probability of finding a full-time job jumps from around .1 at age 20 to more than .8 by age 24. In this pathway, family formation lags education and work. In the mid-to late-20s the probability of being married increases from around .2 at age 24 to close to .6 at age 30. The probability of cohabitation peaks around age 24 at .2 and then declines to around .15 by age 30. Finally, the probability of having a child begins to increase in the late-20s and reaches .4 by age 30. We refer to this pathway as the higher education pathway and it is the best fit for 24 percent of respondents.

The fourth and final pathway that emerges reflects a delayed transition to adulthood. This pathway is characterized by relatively low probabilities of occupying any adult role through the mid-to late-20s. The probability of finding a full-time job remains low through the mid-20s and only reaches around .25 by age 30. The most likely role is parenthood, which steadily increases from about .05 at age 18 to a little over .4 by age 30. This pathway also comes with a relatively low probability of cohabitation (hovers around .15 throughout the 20s) and also a relatively low probability of marriage (slowly increases from around .2 at age 22 to a little under .4 at age 30). We refer to this pathway as the delayed-transition pathway and it is the best fit for 8 percent of respondents.

The 5-pathway model (see Figure A1, online Appendix) exhibits a high degree of consistency with the 4-pathway model. The work, higher education, and delayed-transition pathways all have virtually the same distributions and characterizations with respect to the conditional item response probabilities as with the 4-pathway model. The difference between the 4- and 5-pathway models lies in the work & family pathway, which splits into two pathways with different trajectories of family formation in the 5-pathway model. The first pathway is characterized by steadily increasing probabilities of marriage and parenthood from less than .2 at age 18 to close to .9 by age 26. This pathway also includes an elevated probability of cohabiting in the early 20s that drops to close to 0 by age 26. We continue to refer to this pathway as the work & family pathway and it is the best fit for 22 percent of respondents. The second pathway maintains the high probability of having a child but with a low probability of being married (around .1 to .15 for most ages). Compared to all other pathways, this pathway is characterized by the highest probabilities of cohabitation. The probability of cohabitation steadily increases from less than .2 at age 18 to over .4 at age 24, but then it levels off and finally dips a little bit to under .4 by age 30. We refer to this pathway as the work & children pathway and it is the best fit for 14 percent of respondents.

Correlates of Pathways to Adulthood

Table 3 reports odds ratios from the 4-pathway model. Panel A reports the contrasts with the higher education pathway as the referent group, Panel B reports contrasts with the work pathway as the referent group, and Panel C reports the final remaining contrast between the work & family and delayed-transition pathways.

Table 3.

Odds ratios from multinomial logistic regression predicting pathway membership.

| Panel A: Higher Edu [ref] | Panel B: Work [ref] | Panel C: Delayed-

trans. [ref] |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wrk & Fam | Work | Delayed-trans. | Wrk & Fam | Delayed-trans. | Wrk & Fam | |

| Wave IV age | 1.36 (0.14) ** | 1.43 (0.14) *** | 2.27 (0.33) *** | 0.95 (0.13) | 1.59 (0.28) ** | 0.60 (0.11) ** |

| Female | 1.50 (0.19) ** | 0.59 (0.08) *** | 1.80 (0.39) ** | 2.53 (0.46) *** | 3.04 (0.77) *** | 0.83 (0.21) |

| Race: Black | 1.34 (0.25) | 0.84 (0.16) | 1.85 (0.49) * | 1.58 (0.41) | 2.19 (0.71) * | 0.72 (0.23) |

| Race: Hispanic | 1.27 (0.28) | 1.14 (0.24) | 1.60 (0.56) | 1.11 (0.34) | 1.40 (0.57) | 0.79 (0.33) |

| Race: Other | 0.90 (0.21) | 0.92 (0.22) | 0.97 (0.34) | 0.98 (0.32) | 1.05 (0.45) | 0.93 (0.40) |

| Two bio parents | 0.53 (0.07) *** | 0.66 (0.09) ** | 0.50 (0.12) ** | 0.80 (0.15) | 0.76 (0.20) | 1.05 (0.29) |

| Par. education | 0.74 (0.03) *** | 0.76 (0.03) *** | 0.76 (0.04) *** | 0.97 (0.05) | 0.99 (0.07) | 0.98 (0.07) |

| Par. income (log) | 0.96 (0.03) | 0.96 (0.04) | 1.01 (0.05) | 1.00 (0.05) | 1.05 (0.07) | 0.96 (0.06) |

| Living environment | 0.75 (0.04) *** | 0.82 (0.05) ** | 0.83 (0.07) * | 0.90 (0.08) | 1.00 (0.10) | 0.90 (0.09) |

| GPA | 0.34 (0.04) *** | 0.37 (0.04) *** | 0.48 (0.08) *** | 0.93 (0.14) | 1.32 (0.26) | 0.70 (0.14) |

| College aspirations | 0.53 (0.05) *** | 0.59 (0.05) *** | 0.41 (0.05) *** | 0.89 (0.11) | 0.70 (0.11) * | 1.27 (0.19) |

| Obese | 0.90 (0.22) | 1.17 (0.28) | 1.54 (0.57) | 0.76 (0.26) | 1.31 (0.58) | 0.58 (0.26) |

| Ever daily smoker | 3.78 (0.62) *** | 2.67 (0.44) *** | 2.55 (0.63) *** | 1.41 (0.33) | 0.96 (0.28) | 1.48 (0.44) |

| Drinking | 0.90 (0.04) * | 0.96 (0.04) | 0.85 (0.07) * | 0.94 (0.06) | 0.89 (0.08) | 1.06 (0.09) |

| Par. obese | 1.18 (0.21) | 1.32 (0.23) | 0.97 (0.26) | 0.90 (0.22) | 0.74 (0.24) | 1.21 (0.38) |

| Par. smokes | 1.82 (0.34) ** | 1.46 (0.26) * | 1.76 (0.46) * | 1.25 (0.32) | 1.20 (0.38) | 1.04 (0.33) |

| Par. drinking | 0.90 (0.05) | 1.05 (0.06) | 0.79 (0.08) * | 0.86 (0.07) | 0.75 (0.09) * | 1.14 (0.14) |

Notes:

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001.

Estimates averaged across 20 multiply imputed datasets. Standard errors in parentheses obtained via the delta method. The model incorporates Add Health wave 1 to 4 longitudinal sample weights.

Before turning to adolescent and parental health behaviors, we consider the sociodemographic correlates of the pathways. Females are associated with an increased likelihood of being members of the work & family and delayed-transition pathways relative to the higher education pathway (ORs = 1.50 and 1.80 respectively), a decreased likelihood of being a member of the work relative to the higher education pathway (OR = .59), and an increased likelihood of being a member of the work & family or the delayed-transition pathways relative to the work pathway (ORs = 2.53 and 3.04 respectively). Relatively few significant associations emerge among the racial/ethnic groups. Living with two biological parents, parent education, and the living environment are all consistently associated with an increased likelihood of membership in the higher education pathway relative to all other pathways.

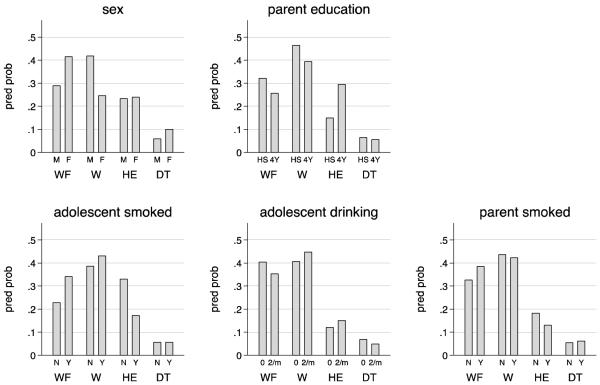

An examination of predicted probabilities aids interpretation of the differences in likelihood of pathway membership.4 The top row of Figure 3 illustrates the predicted probabilities of pathway membership for men and women and for parents with a high school degree versus parents with a four-year degree. Women have higher predicted probabilities of being members of the work & family and delayed-transition pathways than men, but conversely men have a higher predicted probability of being a member of the work pathway than women. In addition, the predicted probabilities of being members of the work & family and work pathways are higher for respondents whose parents earned a high school degree relative to those who earned a four-year degree. In contrast, as one would expect, respondents whose parents earned a four-year degree have a higher predicted probability of being a member of the higher education pathway than respondents whose parents earned a high school degree.

Figure 3. Predicted probabilities of pathway membership.

WF = work & family, W = work, HE = higher education, DT = delayed-transition. For sex M = male and F = female. For parent education HS = high school and 4Y = four-year college degree. For adolescent ever smoked daily and parent smoked N = no and Y = yes. For adolescent drinking 0 = never and 2/m = 2-3 times per month. The predicted probabilities were calculated using the estimates from the 4-pathway model within each complete data set and then averaged over the 20 complete data sets.

As noted above, the difference between the 4-pathway model and the 5-pathway model is that the work & family pathway is divided into two pathways, the work & family pathway and the work & children pathway. Roughly the same pattern of results emerges for the 5-pathway model for family structure, parent socioeconomic resources, and GPA and college aspirations (see Table A1, online Appendix). There are, however, some differences, in the associations for women and blacks. In the 5-pathway model women are more likely to be members of the work & family and work & children pathways relative to the work pathway (ORs = 2.82 and 2.33 respectively). In addition, in the 5-pathway model blacks are associated with a decreased likelihood of being members of the work & family pathway relative to both the delayed-transition pathway (OR = .34) and the work & children pathway (OR = .18). Blacks are associated with an increased likelihood of being a member of the work & children pathway relative to the delayed-transition pathway (OR = 1.86).

Goals 2 and 3 involve an assessment of adolescent and parental health behaviors. Adolescent daily smoking, net of the sociodemographic factors as well as GPA and college aspirations, is consistently associated with an increased likelihood of being a member of any pathway relative to higher education pathway (OR = 3.78 for work & family; OR = 2.67 for work; and OR = 2.55 for delayed-transition). In addition, adolescent drinking is associated with a slightly decreased likelihood of being member of the work & family and delayed-transition pathways relative to the higher education pathway (ORs = .90 and .85 respectively). No significant associations were observed with adolescent obesity.5 The associations for adolescent daily smoking and drinking are largely replicated in the model that allows for 5 pathways. In addition to the associations related to the higher education pathway, adolescent smoking is associated with an increased likelihood of being a member of the work & children pathway relative to the delayed-transition pathway (OR = 1.87). An auxiliary analysis examined interactions between respective adolescent and parental health behaviors with the idea that the co-occurrence of certain health behaviors (e.g., parental and adolescent smoking) might have a stronger association with pathway membership, but no significant interactions were observed.

The bottom row of Figure 3 illustrates predicted probabilities of pathway membership for adolescents who ever smoked daily and those who did not, and adolescents who reported never drinking versus those who reported drinking 2 to 3 times per month. Adolescents who ever smoked daily had noticeably lower predicted probabilities of being on the higher education pathway (pr = .17) than adolescents who did not smoke (pr = .33), while adolescents who ever smoked daily had higher predicted probabilities of being on the work & family (pr = .34 vs. pr = .23) and the work pathways relative to non-smokers (pr = .43 vs. pr = .39). For adolescent drinking a comparison of the predicted probabilities for respondents who never drink versus those who drink 2 to 3 times per month reveals that drinkers have slightly higher predicted probabilities of being members of the work (pr = .45 vs. pr = .41) and higher education pathways (pr = .15 vs. pr = .12) and slightly lower predicted probabilities of being members of the work & family (pr = .35 vs. pr = .40) and delayed-transition pathways (pr = .05 vs. pr = .07).

A similar pattern of associations is observed among the parental health behaviors. Parental smoking is associated with an increased likelihood of being a member of any other pathway relative to the higher education pathway (OR = 1.82 for work & family; OR = 1.46 for work; and OR = 1.76 for delayed-transition). In addition, parental drinking is associated with a decreased likelihood of being a member of the delayed-transition pathway relative to the higher education pathway (OR = .79) and a member of the delayed-transition pathway relative to the work pathway (OR = .75). It is particularly notable that these associations are net of both socioeconomic resources and adolescent health behaviors.

The predicted probabilities illustrated in Figure 3 summarize the patterns for parent smokers and non-smokers. For respondents whose parents smoked, a similar, albeit muted, pattern in the predicted probabilities of pathway membership emerges as observed for respondents who smoked in adolescence. Respondents of parents who smoked had a decreased likelihood of higher education (pr = .13 vs. pr = .18) and an increased likelihood of work & family (pr = .39 vs. pr = .33) relative to respondents who parents did not smoke.

A similar pattern of associations is obtained in the 5-pathway model with the following exceptions. For parental smoking, the association with an increased likelihood remains for the work & children pathway relative to the higher education pathway (OR = 2.16), but not for the work & family relative to the higher education pathway (OR = 1.67 n.s.). For parental drinking, the association with an increased likelihood for the delayed-transition pathway relative to the higher education pathway is no longer statistically significant (OR = .85 n.s.). In both cases, though, the estimates are in the same direction and roughly the same magnitude as observed in the 4-pathway model.

A comparison of the predicted probabilities for the sociodemographic correlates with the predicted probabilities for the adolescent and parental health behaviors provides a sense of the sizes of the associations. The differences in predicted probabilities for adolescents who ever smoked daily (e.g., pr = .17 for higher education pathway) versus non-smokers (e.g., pr = .33 for higher education pathway) are comparable to the differences between having a parent with a high school (e.g., pr = .15 for higher education pathway) versus a four-year college degree (e.g., pr = .29 for higher education pathway)—a notable effect size. By contrast, the gaps in the predicted probabilities for never (e.g., pr = .40 for work & family pathway) versus occasional drinking among adolescents (e.g., pr = .35 for work & family pathway) are roughly half the size of the gaps between having a parent with a high school versus a four-year college degree. Similarly, the differences in predicted probabilities for parent smokers (e.g., pr = .18 for higher education pathway) versus non-smokers (e.g., pr = .13 for higher education pathway) are not as large as the differences for adolescent daily smokers versus non-smokers, which suggest that parental smoking is comparatively distal compared to adolescent smoking with respect to pathways to adulthood.

DISCUSSION

This paper examines whether parental and adolescent health behaviors are associated with pathways to adulthood. Prior research is especially suggestive with respect to parental and adolescent drinking and smoking, which are thought to diminish cognitive, emotional, and social skills. In turn, young people who exhibit such behaviors will experience distinct patterns of school, the workplace, and with respect to family formation. Some evidence also suggests that adolescent BMI can limit educational careers because of stigma and social disapproval encountered in the high school. This study tests these ideas using nationally representative data and latent class models.

With respect to Goal 1, identification of pathways to adulthood, the pathways that emerge among the Add Health respondents are broadly consistent with pathways found in other studies of the transition to adulthood. The 4-pathway model, a pathway characterized by investment in higher education and later family formation, is consistent with similar pathways identified in past studies (Amato et al. 2008; Oesterle et al. 2010; Osgood et al. 2005). In contrast to Osgood et al. (2005), though, this study did not differentiate a pathway involving higher education with respect to the timing of family formation even when considering models allowing for 5 (or 6) pathways.

In the 4-pathway model, a pathway was also identified that involves a transition into work and family formation soon after completing high school. This work & family pathway is akin to the “fast starters” identified by Osgood et al. (2005). In the 5-pathway model, however, the work & family pathway is bifurcated into one pathway that remained similar to the “fast starters” and another that did not involve marriage but rather a degree of cohabitation. This study identified two pathways that involved either working and a low probability of adopting other adult roles or a low probability of adopting all adult roles. The latter pathway, especially, is consistent with the “slow starters” identified by Osgood et al. (2005) and the “inactive” pathway identified by Amato et al. (2008). The identification of the delayed-transition pathway is the primary difference with the pathways that emerge in Oesterle et al.’s (2010) analysis. Finally, this analysis did not identify the pathways involving cohabiting with and without children that emerged in Amato et al.’s (2008) analysis of young women. The few differences may reflect a combination of specific aspects of the samples, a focus on specific subgroups and different age ranges in some past studies, and the slightly different operationalization of the measures of different adult roles across studies. Nevertheless, despite these few differences, these diverse samples yielded largely similar pathways to adulthood when compared to those that we obtained using nationally representative data.

With respect to Goals 2 and 3, sizable associations emerge for adolescent daily smoking and parental smoking and a reduced likelihood of being a member of the higher education pathway as opposed to all other pathways. These findings are noteworthy, especially the magnitude of the associations involving adolescent daily smoking and parental smoking, in that they are net of each other, socioeconomic resources, and other correlates of educational attainment (e.g., GPA and college aspirations). The fact that adolescent daily smoking and parental smoking have independent associations with the higher education pathway suggests that different mechanisms may be operable. The entrance into work prior to or instead of college denotes the transition most strongly predicted by smoking.

It is also noteworthy that the interaction between parental smoking and adolescent daily smoking did not have a significant association with any of the pathways. There is a large body of research showing that health behaviors have genetic origins and a growing number of studies have used Add Health data to show that smoking (Boardman et al. 2008), drinking (Daw et al. 2013), and obesity (North et al. 2010) are all heritable or influenced by specific genetic polymorphisms. There is also an increasingly large body of research demonstrating comparably sized estimates for socioeconomic outcomes such as education (Branigan, McCallum, and Freese 2013; Domingue et al. 2015). Together with work linking socioeconomic and health outcomes to common genetic influences (Boardman, Domingue, and Daw 2015) it is important to consider that some of the links between parental health behaviors, the health behaviors of their children during adolescence, and their subsequent life transitions are mediated through genetic factors shared by parents and their children. Because behaviorally concordant parent-adolescent dyads are more likely to have pairs in which genetic causes of health behaviors are evident, the fact that the interaction term was statistically non-significant suggests that shared genotypes are not the primary mechanism linking these behaviors. Or, rather, that genetic selection into shared health behaviors among parents and children does not affect life transitions any differently than social selection into common health behaviors.

These conclusions may be unique to the birth cohorts covered by Add Health. For example, the prevalence of smoking used to be significantly higher among the most educated when smoking first emerged; it was a socially desirable behavior. But over time, this association has reversed and now the least educated are far more likely to smoke than those with a college degree (Escobedo and Peddicord 1996). Link and Phelan (1995) point to this pattern as evidence of socioeconomic status (SES) as a “fundamental cause” of health for a number of reasons (e.g., exposure to information about health; access to care, prevention, and treatment; and changing patterns of associating with others who smoke).

Pampel (2005) borrows from the work of Simmel (1971) when he describes the way in which upper classes have a need to innovate their styles in order to distinguish themselves from other social classes. A similar process is happening, Pampel (2005) argues, with health behaviors such as smoking, exercise, nutrition, and other health lifestyle behaviors. Thus, cohort becomes fundamental to our understanding of the links between specific health behaviors and education, or more generally, the transition to adulthood. An evaluation of these same transitions with earlier cohorts would provide additional perspective on our findings.

Parental smoking—regardless of timing with respect to pregnancy or much later—is widely thought to adversely affect the physical health of children by way of diverse mechanisms, ranging from prenatal epigenetic modifications to adolescent asthma and other respiratory complications (Been et al. 2014; Knopik et al. 2012). Adolescent daily smoking likely influences socioeconomic attainments through similar but also different processes: it is strongly associated with cognitive impairments in adulthood and this association appears to reflect its effects on the prefrontal cortex, which shows impairments during attentional and working memory tasks (for a review, see Poorthuis et al. (2009)). In other words, prenatal and peri-natal exposures to nicotine and second-hand smoke likely create lasting behavior and health problems, and adolescent daily smoking appears to directly affect skills associated with cognitive performance and very likely emotional self-regulation. That these diverse aspects of smoking could have potentially strong implications for status attainment has not been previously noted and clearly deserves further study.

In addition to smoking, adolescent drinking is associated with an increased likelihood of being a member of the higher education and also the work pathways, and a decreased likelihood of membership in work & family and delayed-transition pathways. The association between drinking and college attendance has been noted previously (Crosnoe and Riegle-Crumb 2007). Intriguingly, adolescent daily smoking does not interfere with family formation, but adolescent drinking does. This pattern of results suggests that the detrimental effects of adolescent drinking on family formation may be especially salient among working young adults who are not pursuing higher education.

Alcohol use among parents and adolescent BMI did not differentiate pathways, contrary to expectations. With respect to alcohol use, the null findings may reflect measurement: alcohol use was self-reported by the parent respondent, and perhaps parents are unlikely to report heavy usage. Additionally, mothers are frequently the parental respondent, and heavy drinking is more common among men than women. Given the vast literature on the deleterious consequences of parental drinking for children, the present findings should be viewed in terms of these limits of measurement. With respect to BMI, alternative operationalizations were examined (i.e., different BMI thresholds as well as linear and non-linear continuous BMI measures) and there is no evidence that BMI predicts pathways. It may be that obesity and overweight status are now sufficiently common that they evoke less social disapproval than was experienced by prior cohorts – yet another reason why studies of earlier cohorts would be provide perspective to the present study.

CONCLUSIONS

A few limitations should be noted. First, analyses that rely on the modeling of latent classes—such as the pathways to adulthood in this paper—are not intended to suggest that the population is definitely composed of these distinct groups or that individuals clearly belong to one pathway. Rather, the purpose of these analyses is to generate and test hypotheses about different causes and consequences of different pathways (Nagin and Odgers 2010), which are heuristic types that simplify substantial complexity. In the present case, the analyses have simplified the complexity inherent in the timing and combinations of five different adult roles to a set of pathways similar to those observed in other samples. Latent class analysis is clearly a useful heuristic tool, but one that is not, in itself, definitive.

Second, because the analyses are based on observational data, one needs to be cautious in interpreting the associations as causal. On the one hand, the results demonstrate associations between parental and adolescent health behaviors and subsequent pathways to adulthood, associations that were hypothesized based on well-studied mechanisms. On the other hand, the modeling strategy does not allow one to rule out the possibility that the associations may be biased due to omitted variables. For instance, it is possible that to some extent parental smoking serves as a proxy for poor parenting behaviors more generally. Indeed, the challenge of disentangling these issues of timing—and highly correlated environment risks—is notoriously difficult in smoking research.

Third, there are limitations related to the availability of measures in Add Health. More complete information on employment trajectories and the types of jobs respondents held is unavailable. Such data would allow for a better characterization of the transition into work. Also, more complete information about enrollment in school and whether respondents were living with any children is also unavailable. It is notable, however, that despite these limitations the pathways that emerge are consistent with those found in past studies. Finally, the data are also limited in that health behaviors of parents and adolescents are only available at one point in time. Ideally one would like information about parents’ and children’s health behaviors extending from birth (and even parent health behaviors while carrying the child) through late adolescent prior to the period of the transition to adulthood. Such data would help untangle different mechanisms, such as cumulative exposure and multiple forms of health-behavior related disadvantage, linking, for instance, parental and adolescent smoking to pathways involving higher education and also help establish how trajectories of health behaviors relate to the transition to adulthood.

Despite these limitations, the joining of life course distinctions, health behaviors, and the transition to adulthood offers exciting possibilities for the study of health-related mechanisms by which socioeconomic status is reproduced across the generations. This analysis suggests the important roles of both parental and adolescent daily smoking in shortening educational careers; such youth then engage in the workplace and family formation. Further, adolescent drinking may come with delayed family formation among workers. When combined, parental/adolescent smoking and adolescent drinking may be associated with displacement from the basic institutions of school, work, and family. An abundance of evidence suggests that parental drinking could also be implicated, although the present measure is not ideal. These associations are descriptive and future research should examine how social, psychological, and biological levels of analysis conjoin to create such patterns over many years of childhood and adolescence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis. This paper was supported by the NICHD (R01 HD061622-01, Shanahan PI).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

See Harris et al. (2009) for a detailed discussion of the construction of the Add Health sample.

Indicators for every other age, rather than every age, are used to reduce the number of measures used in the estimation of the latent classes. This helps mitigate issues with data sparseness that arise when using a large number of measures (Collins and Lanza 2010).

Preliminary analyses examined the possibility of including 2-year degrees as a separate category or including 2-year degrees in the higher education series. Among the respondents only a small percentage (9 percent) reported a 2-year degree as their highest level of education, thus it was not feasible to construct a separate series and incorporating them into the higher education series did not alter the results.

Predicted probabilities were computed by setting the focal covariate to a given value (e.g., 1 for females, 0 for males) while allowing all other covariates to maintain the values of the individual cases in the data.

Auxiliary analyses (not reported) tested whether adolescent obesity had a stronger association with pathways to adulthood for women than for men by including an interaction term (female X adolescent obesity) in the model. None of the interactions were statistically significant.

Contributor Information

Shawn Bauldry, University of Alabama-Birmingham.

Michael J. Shanahan, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill

Ross Macmillan, Universita Commerciale Luigi Bocconi, Italy.

Richard A. Miech, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Jason D. Boardman, University of Colorado-Boulder

Danielle Dean Veronica Cole, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

REFERENCES

- Amato Paul R., et al. Precursors of Young Women’s Family Formation Pathways. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:1271–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato Paul R., Kane Jennifer B. Life-Course Pathways and the Psychosocial Adjustment of Young Adult Women. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73(1):279–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00804.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averett, Susan and Sanders Korenman The Economic Reality of the Beauty Myth. Journal of Human Resources. 1994;31:304–30. [Google Scholar]

- Averett Susan L., Sikora Asia, Argys Laura M. For Better or Worse: Relationship Status and Body Mass Index. Economics & Human Biology. 2008;6(3):330–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsa Ana I., Giuliano Laura M., French Michael T. The Effects of Alcohol Use on Academic Achievement in High School. Economics of Education Review. 2011;30:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A Developmental Perspective on Adolescent Drug Abuse. Advances in Alcohol & Substance Abuse. 1985;4(3-4):41–66. doi: 10.1300/J251v04n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker Gary S. A Treatise on the Family. Harvard university press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Been Jasper V., et al. Effect of Smoke-Free Legislation on Perinatal and Child Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Lancet. 2014;383(9928):1549–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boardman Jason D., Alexander Kari B., Miech Richard A, MacMillan Ross, Shanahan Michael J. The Associated between Parent’s Health and the Educational Attainment of Their Children. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;75:932–39. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boardman Jason D., Domingue Benjamin W., Daw Jonathan. What Can Genes Tell Us about the Relationship Between Education and Health? Social Science & Medicine. 2015;127:171–80. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boardman Jason D., Saint Onge Jarron M., Haberstick Brett C., Timberlake David S., Hewitt John K. Do Schools Moderate the Genetic Determinants of Smoking? Behavior Genetics. 2008;38(3):234–46. doi: 10.1007/s10519-008-9197-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branigan Amelia R., McCallum Kenneth J., Freese Jeremy. Variation in the Heritability of Educational Attainment: An International Meta-Analysis. Social forces. 2013;92(1):109–40. [Google Scholar]

- Brook Judith S., Richter Linda, Whiteman Martin, Cohen Patricia. Consequences of Adolescent Marijuana Use: Incompatibility with the Assumption of Adult Roles. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 1999;125(2):193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bublitz Margaret H., Stroud Laura R. Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy and Offspring Brain Structure and Function: Review and Agenda for Future Research. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;14(4):388–97. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case Anne, Fertig Angela, Paxson Christina. The Lasting Impact of Childhood Health and Circumstance. Journal of Health Economics. 2005;24:365–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maternal Socialization of Adolescent Smoking: The Intergenerational Transmission of Parenting and Smoking. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34(6):1189. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins Linda M., Lanza Stephanie T. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis: With Applications in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Conley Dalton, Glauber Rebecca. Gender, Body Mass, and Socioeconomic Status: New Evidence from the PSID. Advances in health economi1cs and health services research. 2007;17:253–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius Marie D., Day Nancy L. Developmental Consequences of Prenatal Tobacco Exposure. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2009;22:121–25. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328326f6dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe Robert. The Connection Between Academic Failure and Adolescent Drinking in Secondary School. Sociology of Education. 2006;79(1):44–60. doi: 10.1177/003804070607900103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe Robert. Gender, Obesity, and Education. Sociology of Education. 2007;80:241–60. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe Robert, Muller Chandra. Body Mass Index, Academic Achievement, and School Context: Examining the Educational Experiences of Adolescents at Risk of Obesity. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2004;45(4):393–407. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe Robert, Riegle-Crumb Catherine. A Life Course Model of Education and Alcohol Use. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007;48:267–82. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossman Ashley, Sullivan Deborah Anne, Benin Mary. The Family Environment and American Adolescents’ Risk of Obesity as Young Adults. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63(9):2255–67. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daw Jonathan, et al. Genetic Sensitivity to Peer Behaviors 5HTTLPR, Smoking, and Alcohol Consumption. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2013;54(1):92–108. doi: 10.1177/0022146512468591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingue Benjamin W., Belsky Daniel W., Conley Dalton, Harris Kathleen Mullan, Boardman Jason D. Polygenic Influence on Educational Attainment: New Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. AERA Open. 2015;1(3):1–13. doi: 10.1177/2332858415599972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan Greg J., Wilkerson Bessie, England Paula. Cleaning Up Their Act: The Effects of Marriage and Cohabitation on Licit and Illicit Drug Use. Demography. 2006;43:691–710. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddings Wesley, Marchenko Yulia. Diagnostics for Multiple Imputation in Stata. Stata Journal. 2012;12(3):353–67. [Google Scholar]

- Eide Eric R., Showalter Mark H. Estimating the Relation Between Health and Education: What Do We Know and What Do We Need to Know? Economics of Education Review. 2011;30:778–91. [Google Scholar]

- Escobedo Luis G., Peddicord John P. Smoking Prevalence in US Birth Cohorts: The Influence of Gender and Education. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(2):231–36. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Haishan, Goldman Noreen. Incorporating Health into Models of Marriage Choice: Demographic and Sociological Perspectives. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996:740–58. [Google Scholar]

- Glass Christy M., Haas Steven A., Reither Eric N. The Skinny on Success: Body Mass, Gender and Occupational Standing across the Life Course. Social Forces. 2010;88(4):1777–1806. doi: 10.1353/sof.2010.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göhlmann Silja, Schmidt Christopher M., Tauchmann Harald. Smoking Initiation in Germany: The Role of Intergenerational Transmission. Health economics. 2010;19:227–42. doi: 10.1002/hec.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman Noreen. Marriage Selection and Mortality Patterns: Inferences and Fallacies. Demography. 1993;30:189–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman Elizabeth, Hinden Beth R., Khandelwal Seema. Accuracy of Teen and Parental Reports of Obesity and Body Mass Index. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1):52–58. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham John W., Olchowski Allison E., Gilreath Tamika D. How Many Imputations Are Really Needed? Some Practical Clarifications of Multiple Imputation Theory. Prevention Science. 2007;8(3):206–13. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas Steven A., Glymour M. Maria, Berkman Lisa F. Childhood Health and Labor Market Inequality over the Life Course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2011;52:298–313. doi: 10.1177/0022146511410431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris Kathleen Mullan, et al. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research Design. 2009 Retrieved ( http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design)

- Harris Kathleen Mullan. An Integrative Approach to Health. Demography. 2010;47:1–22. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill Shirley Y., Lowers Lisa, Locke-Wellman Jeannette, Shen SA. Maternal Smoking and Drinking during Pregnancy and the Risk for Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2000;61(5):661. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Hippel Paul T., Lynch Jamie L. Why Are Educated Adults Slim— Causation or Selection? Social Science & Medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan Dennis P. The Variable Order of Events in the Life Course. American Sociological Review. 1978;43(4):573–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hout Michael. Social and Economic Returns to College Education in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology. 2012;38:379–400. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong Andrea M., et al. Characterizing the Life Stressors of Children of Alcoholic Parents. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:819–32. doi: 10.1037/a0013704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson Margot I. Understanding Links Between Adolescent Health and Educational Attainment. Demography. 2009;46:671–94. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]