Abstract

Although one-third of children of immigrants have undocumented parents, little is known about their early development. Using data from the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey and decennial census, we assessed how children’s cognitive skills at ages 3 to 5 vary by ethnicity, maternal nativity, and maternal legal status. Specifically, Mexican children of undocumented mothers were contrasted with Mexican children of documented mothers and Mexican, white, and black children with U.S.-born mothers. Mexican children of undocumented mothers had lower emergent reading skills than all other groups and lower emergent mathematics skills than all groups with U.S.-born mothers. Multilevel regression models showed that differences in reading skills are explained by aspects of the home environment, but the neighborhood context also matters. Cross-level interactions suggest that immigrant concentration boosts emergent reading and mathematics skills for children with undocumented parents, but does not similarly benefit children whose parents are native born.

Keywords: Children, cognitive skills, Mexican, immigrants, undocumented, neighborhood

1. Introduction

The changing composition of the child population of the United States has drawn attention to new sources of diversity in children’s outcomes. Immigration has contributed to well-known shifts in the ethnic landscape and the nativity of parents (Frey, 2011), but it has also driven changes that are less readily observable but potentially critical to children’s life chances. One such change that is of widespread interest is the growing share of children with undocumented parents (Glick, 2010). Nearly one in every four U.S. children has at least one immigrant parent and one-third of children in immigrant families have undocumented parents (Guerrero et al., 2013; Nwosu, Batalova, and Auclair, 2014).

Although knowledge about the children of immigrants has accumulated rapidly in recent years, much less is known about the roughly 5.5 million children with undocumented parents (Passel and Cohn, 2011). Research on these children has been severely limited by the lack of information on the legal status of immigrants in the vast majority of large-scale surveys. The scarcity of such data is particularly problematic for studies of Mexican-origin children, who currently comprise about 17% of all U.S. children but about 40% of children with immigrant parents and 70% of children with unauthorized immigrant parents (Passel and Cohn, 2011; U.S. Census Bureau, 2013).

A key issue for understanding the life chances of Mexican children of immigrants is whether having unauthorized parents negatively affects early development (Yoshikawa and Kholoptseva, 2013). As noted, this issue is understudied because few data sources include measures of parental legal status, and even fewer also assess child development (Yoshikawa and Kalil, 2011). Apart from ethnographic research, the existing literature is based on studies that draw inferences from comparisons of: (a) ethnic groups that differ with respect to the proportion of immigrants that are undocumented and (b) citizens and non-citizens. Such studies provide useful information, but fail to demonstrate whether and how children with undocumented parents differ from children with documented or U.S.-born parents. Thus, scholars increasingly argue that more systematic collection and analysis of data from direct questions about the legal status of immigrant parents is necessary to address how this relatively neglected dimension of diversity affects child development (Glick, 2010; Yoshikawa and Kalil, 2011).

Young children’s cognitive skills are fundamental building blocks for later success. In particular, extensive research demonstrates that reading and mathematics skills at the point of school entry are critical to later academic achievement (Duncan et al., 2007; Entwisle and Alexander, 2002). Prior studies also document that Mexican-origin children are disadvantaged with respect to early cognitive development and those with immigrant parents have lower cognitive skills than their counterparts with U.S.-born parents (Fuller et al., 2009; Guerrero et al., 2013; Padilla et al., 2002). In addition, indirect evidence from one study suggests that early cognitive achievement is lower among children with undocumented versus documented immigrant parents (Yoshikawa, 2011). However, this issue has not been investigated with representative survey data and direct measurement of parental legal status.

Using one of the few representative data sources with detailed questions on the legal status of immigrants, the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey (L.A. FANS), this research focuses on the cognitive skills of children ages 3 to 5. We first examine whether and how emergent reading and mathematics skills vary by ethnicity, maternal nativity, and maternal legal status. This involves contrasts between Mexican children with undocumented, documented (permanent resident and naturalized), and U.S.-born mothers. Although we focus primarily on Mexican-origin children, white and black children with U.S.-born mothers are also incorporated into the analysis as benchmarks for assessing relative standing.1 Several potential explanations for the observed associations are evaluated and discussed.

2. Background

2.1. Immigration Status

Approximately 91% of children under the age of six who have undocumented parents are American citizens by birth (Yoshikawa and Kholoptseva, 2013). Nonetheless, these children face unique disadvantages as a result of a constellation of factors related to their parents’ unauthorized status. Immigration statuses reflect hierarchical positions established by institutions through laws, rules and administrative procedures. Among the foreign born, naturalized citizens are at the top of this hierarchy. Petitioners for naturalization must meet a strict set of requirements, including continuous residence in the United States, knowledge of English and civics, compliance with laws, and evidence of “good moral character,” before taking an oath of allegiance. Lawful permanent residents (LPRs) are in a middle position; they are authorized to live and work in the United States and to receive public benefits after a probationary period. These documented immigrants are issued “green cards” that verify their legal status. At the bottom of the hierarchy are undocumented residents without a green card or a visa permitting temporary residence (Romero, 2009).

These legal status distinctions both influence and are influenced by the characteristics of immigrants. For example, immigrants with lower human capital (education, skills and abilities valued by employers) are more likely to enter the United States without legal authorization than those with higher levels of human capital. In turn, lack of documentation reinforces disadvantage because it limits access to desirable jobs and benefits that are restricted to legal residents (Flippen, 2012).

Among Mexicans, undocumented immigrants have very low human capital and often work in low-wage jobs with little security (Flippen, 2012; Hall, Greenman and Farkas, 2010; Massey and Gentsch, 2014). Consequently, children with undocumented parents have a high rate of poverty, relative to children with documented or citizen parents. In addition, unauthorized parents are ineligible for federal benefits for adults that might improve family well-being (Yoshikawa and Kholoptseva, 2013). While their citizen children are eligible for public benefits, undocumented parents’ unfamiliarity with public programs and fear of detection may decrease their likelihood of accessing these benefits for their children. These disadvantages may be compounded by psychological distress resulting from perceived social exclusion and a lack of legal rights (Louie, 2012).

The relatively low human capital and earnings of undocumented immigrants, a desire to remain unnoticed, and preferences for living near Spanish-speaking co-ethnics also may influence the types of neighborhoods in which the undocumented settle. One recent study (Hall and Greenman, 2013) of subjective assessments of neighborhood quality in a nationally-representative sample suggests that Mexican and Central American undocumented immigrants live in less-advantaged neighborhoods than their documented counterparts. In unadjusted comparisons, undocumented immigrants ranked at or near the bottom on multiple dimensions of neighborhood quality in comparisons with documented Mexican/Central American immigrants and U.S.-born Latinos, whites and blacks. In multivariate models that controlled for various socioeconomic and immigration-related characteristics, lacking authorization to live in the United States continued to be associated with poor neighborhood quality, including lack of services and environmental problems.

Still, theories of spatial assimilation provide mixed expectations regarding the consequences of immigrant concentration in disadvantaged communities. The classic view regards spatial assimilation as a process that goes hand-in-hand with social and economic mobility. Newcomers initially settle in communities with other immigrants, but over time they and their descendants become more spatially integrated with the native-born population in neighborhoods with greater resources (Waters and Pineau, 2015). Although this perspective is blind to the role of legal status, it implies that residence in poor, predominantly immigrant neighborhoods mainly reflects recency of migration to the United States and any negative impacts on children are likely to be transitory. Other approaches are less sanguine, arguing that economically disadvantaged immigrant communities lack the institutional and community resources needed for socioeconomic progress, thereby greatly reducing the opportunities available to immigrants and their children. In short, poor neighborhood quality may result in isolation and the intergenerational transmission of disadvantage.

On the other hand, it is important to consider the potentially positive aspects of immigrant or ethnic concentration on immigrants and their children. Although immigrant concentration often goes hand-in-hand with inadequate educational, health, and social services, these disadvantages may be offset to some extent by immigrant communities that promote social cohesion and enhance family functioning (Leventhal and Shuey, 2014). There is some evidence (albeit mixed) that living in an immigrant or ethnic enclave may be associated with more abundant social ties and greater social support (Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2013). Neighbors may provide information, assistance with everyday tasks, and emotional support, which may be critical for relatively recent immigrants who otherwise might be isolated (Viruell-Fuentes and Schulz, 2009). This may have positive repercussions for the development of children (see below).

2.2. Cognitive Achievement in Early Childhood

Numerous studies document a strong relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and cognitive development in early childhood, but there is no clear consensus on the specific mechanisms involved (Bornstein and Bradley, 2012). A few scholars argue that this reflects the intergenerational transmission of innate ability (Hernstein and Murray, 1994), but most researchers emphasize the critical role played by the home environment (Anger and Heineck, 2010; Bradley et al, 1993; Crane, 1996; Cunha and Heckman, 2007; Currie and Duncan, 1995; Farkas, 2004). Moreover, the lack of support for genetic explanations of ethnoracial group differences in cognitive test scores suggests that members of disadvantaged groups are less able to develop their full potential because of limited resources, broadly conceived (Fisher et al., 1996; Nisbett et al, 2012). Thus, the well-documented cognitive skill gaps by race-ethnicity at the start of kindergarten are explained in terms of group differences in SES (García, 2015).

Family SES influences young children’s cognitive skills through both the home learning environment and parents’ ability to access high-quality early childhood programs outside the home (García, 2015). As noted, SES is also a key determinant of neighborhood choice, but for preschool children, neighborhood characteristics are likely to influence cognitive development indirectly by affecting parental well-being, the home environment, and child care availability or quality (Sastry and Pebley, 2010). This is because young children’s social lives occur primarily within the family or in other supervised environments (e.g. child care settings) accessed by their parents.

Extensive research links parental education and family income to aspects of the home penvironment that shape development, including the availability of learning materials and cognitively stimulating interactions (Lareau, 2003; Suárez-Orozco, Yoshikawa and Tseng, 2015). The quality of parenting, as reflected in parental responsiveness and family routines, also varies with SES and contributes to early development (Evans, 2004). Additionally, some evidence suggests that economic strain increases parental stress and depression, which in turn may reduce the quality of parenting (Conger, Reuter and Conger, 2000). Finally, access to center-based child care and preschool is constrained by low income, and participation in early education programs is especially beneficial to low-income children and dual-language learners (Duncan and Murnane, 2014; NICHD ECCRN, 2005). Given the marked variation in SES across ethnoracial groups, these processes play a significant role in early cognitive skill gaps by race-ethnicity (García, 2015).

Studies of Mexican children’s early cognitive achievement are consistent with the broader emphasis on SES and the home environment. Based on data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Studies - Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), Fuller et al. (2009) found significant disparities in children’s cognitive growth between 9 months and 24 months of age, as measured by the Bayley mental score. Cognitive growth and Bayley mental scale scores at 24 months were significantly lower for Mexican-origin children than for white children, and the rising gap was partially attributable to their mothers’ lower levels of education, relatively weak pre-literacy practices, and a high ratio of children per resident adult. Guerrero et al. (2013) found that the cognitive gap between Mexican and white children in the ECLS-B persisted at 48 months of age. Using child data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, Padilla et al. (2002) similarly found that the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT-R) scores of Mexican infants ages 3–4 lagged considerably behind those of white children, controlling for socioeconomic and household resource variables. The authors emphasized the low education of Mexican mothers as a key factor, despite its inability to fully explain the test score gap.

Other studies have emphasized country-of-origin differences in cognitive achievement among legal immigrants. Using the New Immigrant Survey, a study based on a nationally representative sample of legal immigrants, Pong and Landale (2012) showed that Mexican children of immigrants had lower test scores at ages 6–12 than non-Hispanic children of immigrants. Pre-migration parental attributes, especially parental education, accounted for the test score disadvantage of Mexican-origin children. Parents’ pre-migration education was also significantly related to the level of cognitive stimulation in the home. In short, this research demonstrated that what parents bring to the United States and their circumstances after arrival jointly influence children’s cognitive development.

2.3. Parental Legal Status and Early Cognitive Achievement

In one of the few studies to draw attention to the cognitive development of preschool children with undocumented parents, Yoshikawa (2011) conducted a qualitative inquiry based on semi-structured interviews and participant observation with 11 Mexican families (10 undocumented) and 9 Dominican families (1 undocumented) in New York City. He also analyzed quantitative data from a birth cohort in the city that included direct measures of cognitive skills but did not include parents’ legal status. In interpreting results from the latter data, Yoshikawa used Mexican ethnicity and the absence of resources requiring identification as proxies for undocumented status.

Yoshikawa (2011) concluded that at 24 months, the lower cognitive skills of children with undocumented parents are attributable to economic hardship and maternal psychological distress or depression. At 36 months, the most important pathways are parental working conditions and the use of center-based child care. Yoshikawa and Kholoptseva (2013) argued that the low wages and poor working conditions of unauthorized parents affect children’s cognitive development because they increase parental distress, which in turn may reduce the quality of parenting.

Although a potentially valuable contribution on an understudied topic, a major drawback of the quantitative analysis was its reliance on a proxy measure of parental legal status. We overcome this limitation with data from the L.A. FANS, a survey that included direct questions on documentation status. These data allowed us to analyze the role of maternal legal status in the cognitive achievement of Mexican children ages 3 to 5. Several specific research questions guide the analysis: (1) Do cognitive skills vary by maternal legal status among Mexican children of immigrants? (2) Are there substantial early test score gaps between Mexican children of undocumented immigrants and Mexican, white and black children of native-born mothers? (3) To what extent can early cognitive skill disparities be explained by group differences in socioeconomic status, family composition, maternal distress, and the home learning environment? (4) To what extent are group differences modified by key attributes of the neighborhood environment, particularly socioeconomic conditions and immigrant concentration?

3. Data and Methods

Our analysis draws from two data sources. Data on children and their families are from the first wave of the L.A. FANS, which was administered to families living in Los Angeles County in 2000–2002. The survey was based on a stratified random sample of 65 neighborhoods (identified via census tract), with 50 households from each. Within each selected household, one adult was sampled at random to answer an adult survey and one child was sampled at random for a child-focused module (Peterson et al., 2004). To report on sampled children, a primary caregiver (almost always the mother) was selected to answer caregiver and parent modules. These individuals also completed the adult survey if they had not already done so as the randomly selected adult in the household. In addition, one sibling of the focal child was randomly selected for inclusion among those in the household who were under age 18 and had the same mother and primary caregiver. All survey components were available in English and Spanish. In addition, contextual data measured at the census tract level were drawn from the 2000 decennial census and merged to the L.A. FANS to describe the neighborhood of residence.

Our analytic sample is restricted to children ages 3 to 5, including Mexican children with undocumented or naturalized/documented foreign-born mothers and Mexican, white, and black children with U.S.-born mothers. Starting with all 3- to 5-year-olds in the child sample (N=687), we first restricted our sample to those who were matched to a primary caretaker who completed an adult questionnaire, a parent questionnaire, and a primary caregiver questionnaire (N=570). After excluding 8 children who had missing values on the sample stratification variable, 20 children who had missing values on the geographic identifier, and 146 children in groups other than those identified above, 396 children remained for analysis.

The mi impute procedure in Stata was used for missing data. Twenty-five imputed datasets were created and the results for each were combined to take uncertainties associated with incomplete information into account in the estimation of coefficients and standard errors (see Rubin 1987).

3.1. Variables

3.1.1. Dependent variables

The L.A. FANS measured the cognitive skills of children ages 3 to 5 with two subtests of the Woodcock Johnson-Revised Test of Achievement (WJ-R): the Letter-Word Identification (LWI) and Applied-Problems (AP) assessments. The LWI test measures emergent reading skills through activities such as identifying letters and simple words as well as matching pictures with words. The AP test measures emergent mathematics skills by assessing how well children can solve numerical or spatial problems presented verbally with accompanying illustrations. These tests were administered in English or Spanish depending on the language ability and preference of the test taker. Age-standardized scores with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15 are analyzed here (McGrew and Woodcock, 2001).

3.1.2. Race-ethnicity, nativity, and legal status

The primary independent variable was constructed from information on ethnicity, parental nativity and legal status. All foreign-born adult sample members were asked a series of questions to determine their legal status at the time of the survey. The first was whether they were naturalized citizens. Those who were not citizens were then asked whether they had a “green card” or permanent resident status. Immigrants who were not citizens and did not have a green card were next asked whether they had refugee, asylee, or Temporary Protected Status. Finally, those who did not have one of these statuses were asked if they had a valid visa for temporary residence. These questions were used to identify those who were authorized (naturalized citizen or documented) and those who were not authorized (undocumented) to live in the United States. Immigrants who were not naturalized, not permanent residents, not refugees/asylees and not in possession of a valid visa were coded as undocumented. Bachmeier, Van Hook and Bean (2014) demonstrate that respondents to the L.A. FANS were willing to answer these questions and the profile of undocumented immigrants resulting from these procedures is consistent with profiles produced from other sources.

Our primary interest is in the roles of parental nativity and legal status in the cognitive achievement of Mexican-origin children, but white and black children with U.S.-born mothers provide useful comparison groups. Thus, we distinguished five groups based on the status of mothers, including children of: (a) Mexican undocumented immigrants, (b) Mexican naturalized or documented immigrants, (c) U.S.-born Mexicans, (d) U.S.-born whites, and (j) U.S.-born blacks. Due to sample size limitations it was not possible to differentiate Mexican children with naturalized citizen mothers from those with mothers who were legal permanent residents.

3.1.3. Individual and family variables

Other demographic and family characteristics serve as explanatory or control variables. The sex of the child was controlled in all multivariate models (1=female, 0=male). SES and family composition were measured with maternal education, poverty, single parenthood, and the number of children in the household. Maternal education was coded ‘1’ if the mother did not complete high school and ‘0’ if she completed high school or more. Family poverty was measured using the federal poverty thresholds for 2001. In addition, a continuous measure of the number of children in the household is included.

Maternal depression is a dichotomous variable that was constructed from scores on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-Form (CIDI-SF) depression inventory. The CIDI-SF yields a score that ranges from 0.0 to 1.0 and represents the probability that a respondent would meet the criteria for major depression if given the full CIDI interview. Respondents were coded as depressed (1) if their probability of depression was greater than 0.5, and not depressed (0) otherwise.2

Several measures of the cognitive environment in the home were included. The mother’s cognitive skills were measured with the single assessment administered to primary caregivers, the WJ-R Passage Comprehension (PC) assessment. Administered in Spanish or English according to the preference of the mother, the PC assessment requires the test taker to point to the picture represented by a phrase or to read short passages and identify missing key words. Standard scores were used in this study. Although these scores are undoubtedly related to educational attainment, the mother’s passage comprehension (PC) score more directly gauges verbal skills and thus may be considered an indirect measure of the verbal stimulation in the home environment. Nisbett et al. (2012) indicate that parents who have high SES—who also have relatively high cognitive test scores—are likely to use a larger and more diverse vocabulary in the home and to engage in more frequent verbal interaction with their young children than parents with low SES. Additional measures of the cognitive home environment are learning materials in the home and how often the mother reads to the child. Learning materials in the home is an additive index constructed from four dichotomized measures that are not specific to children: whether the family regularly gets at least one magazine, whether the family subscribes to a newspaper, whether there are more than 20 books in the home, and whether there is a computer in the home that the child uses. In addition, we included an ordinal measure of how often the mother reads to the child, which has six values ranging from ‘never’ to ‘every day.’ Another key predictor is whether the child is currently enrolled in center-based child care (1=yes, 0=no). 3

3.1.4. Neighborhood characteristics

In keeping with previous studies that have assessed neighborhood effects (Sampson, Morenoff, and Gannon-Rowley, 2002), we conducted a principal component factor analysis of eight structural characteristics of Los Angeles county census tracts drawn from the 2000 decennial census to create measures of the neighborhood environment. This culminated in the creation of factor scores that reflect the three underlying factors that emerged from this procedure: concentrated disadvantage, concentrated affluence, and immigrant concentration. Concentrated disadvantage and concentrated affluence measure the socioeconomic characteristics of neighborhoods (Browning et al., 2013). Our measure of concentrated disadvantage is based on the percentages of individuals below the poverty line, on public assistance, and unemployed. Concentrated affluence is based on the percentage of individuals with at least a bachelor’s degree; the percentage in professional, administrative, or managerial positions; and the percentage of families with an annual income greater than $75,000. Immigrant concentration is measured from the percentage Hispanic and the percentage who were not citizens. Needless to say, higher scores reflect higher levels of each neighborhood attribute.4

3.2. Analytic strategy

To adjust for the complex sample design and nested structure of the L.A. FANS, we used survey data analysis procedures in Stata and hierarchical linear modeling. These procedures adjust standard errors for sample design features, including stratification and clustering. Our data are structured hierarchically, with children nested within neighborhoods. Thus, we employed a two-level hierarchical linear model with random intercepts to obtain the parameter estimates and standard errors for the analyses of children’s Letter-Word Identification (LWI) and Applied Problems (AP) scores. All null multilevel models had statistically significant variance of the intercept indicating that the multilevel modeling approach was a superior alternative to ordinary least squares (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Thus, neighborhood context may contribute substantially to variation at the individual level.

After showing the bivariate associations, results from six multivariate models are presented for each dependent variable. The first four models focus on the individual-level measures, proceeding sequentially from a baseline multivariate model that includes the main predictor of interest along with socioeconomic and demographic covariates (Model 1) to models that add measures of maternal depression (Model 2), the cognitive home environment (Model 3), and enrollment in center-based child care (Model 4). The last two models demonstrate the role of neighborhood characteristics by showing the direct effect of each neighborhood characteristic (Model 5) and results from the one cross-level interaction that achieved significance (Model 6). All analyses are weighted using the child sample weight. Contextual-level weights were created and rescaled to remove the unequal probabilities of selection for the neighborhoods (West, Welch and Galecki, 2014). One-tailed tests were used to assess statistical significance because our expectations for all relationships are directional.

4. Findings

4.1. Descriptive

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for all variables by ethnicity and mother’s immigration status, with significant differences between Mexican children of undocumented mothers and each other group identified. These results reveal substantial similarities in maternal characteristics, home environments, and child care use between Mexican children with undocumented and documented mothers. But these groups differ with respect to two variables that potentially play key roles in cognitive development: mother’s education and mother’s Passage Comprehension (PC) score. On each of these variables, children with undocumented mothers are significantly more likely to be disadvantaged than children with documented mothers.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics by Ethnicity/Mother’s Immigration Status, Ages 3–5

| Variable | Mexican Undocumented | Mexican Naturalized or Documented | Mexican U.S. Born | White U.S. Born | Black U.S. Born |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woodcock Johnson Standardized Test Score | |||||

| Letter-Word Identification | 92.26 | 97.27 a | 97.23 a | 103.63 a | 99.44 a |

| Applied Problems | 89.17 | 91.96 | 92.18 | 108.78 a | 98.96 a |

| Child/Mother/Family Characteristics | |||||

| Child female (%) | 51.1% | 54.5% | 60.4% | 47.7% | 54.5% |

| Mother’s education < high school (%) | 81.7% | 64.0%a | 28.4% a | 5.6% a | 21.9% a |

| Poor family (%) | 66.4% | 54.2% | 37.6% a | 35.9% a | 35.5% a |

| Single parent (%) | 40.1% | 37.0% | 41.5% | 23.7% a | 83.4% a |

| Number of children in household | 2.87 | 3.05 | 2.54 a | 2.21 a | 3.04 |

| Mother depressed (%) | 9.2% | 15.0% | 22.7% a | 16.9% | 31.3% a |

| Mother’s Passage Comprehension | 71.10 | 76.33 a | 85.53 a | 99.24 a | 83.46 a |

| Learning materials in home | 0.86 | 1.21 | 1.47 a | 2.26 a | 1.91 a |

| How often mother reads to child | 3.85 | 4.10 | 4.56 a | 5.03 a | 4.54 a |

| Attends center-based child care (%) | 5.2% | 5.9% | 18.4% a | 39.0% a | 32.0% a |

| Neighborhood Characteristics | |||||

| Concentrated Disadvantage | 0.82 | 0.63 | 0.24 a | −0.40 a | 0.83 |

| Concentrated Affluence | −0.79 | −0.71 | −0.54 a | 0.40 a | −0.56 a |

| Immigrant Concentration | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.49 a | −0.63 a | 0.22 a |

| Unweighted N=396 | 106 | 111 | 73 | 70 | 36 |

Data Source: Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey; 2000 decennial census

Significantly different from Mexican undocumented, p<.05 (one-tailed test)

The former group also faces markedly different circumstances than children with U.S.-born mothers. As expected, children of the undocumented are especially likely to live below the poverty line (66%) and have mothers with less than a high school education (82%). Moreover, undocumented mothers have relatively low scores on the cognitive skill test and their children are relatively less likely to have learning materials in the home, to be read to, and to attend center-based child care. The difference in center care is especially striking. Only 5% of 3- to 5-year-old Mexican children with undocumented mothers attended center-based child care centers. Among children with U.S.-born mothers, the comparable figures are 18% for Mexicans, 39% for whites, and 32% for blacks. In contrast to this constellation of disadvantages, children with undocumented mothers may benefit from relatively low levels of maternal depression—9% compared to 23% for Mexican and 32% for black children with native-born mothers.

4.2. Hierarchical linear models

4.2.1. Letter-word identification

Table 2 provides results from hierarchical linear models of children’s emergent reading (LWI) test scores. The first column shows the bivariate relationships between each predictor and the standard LWI score. The pattern for ethnicity and immigration status shows that Mexican children with naturalized or documented immigrant mothers have significantly higher test scores than Mexican children with undocumented mothers. Children with Mexican, white or black U.S.-born mothers also have LWI test scores that are significantly higher than those of Mexican youth with undocumented mothers.5 With the exception of the child’s gender and maternal depression, all predictors are significantly related to children’s LWI scores in the bivariate models. As for socioeconomic and family circumstances, low maternal education, poverty, single parenthood, and a larger number of children in the household are negatively related to LWI scores. Among the home environment and parenting variables, the mother’s PC test score, learning materials in the home, and more frequent reading to the child are associated with higher LWI test scores, as is attending center-based child care.

Table 2.

HLM Analysis of Woodcock Johnson Letter-Word Identification Standard Scores, Ages 3–5

| Variable | Bivariate | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity/Mother’s Immigration Status | |||||||

| Mexican undocumented | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) |

| Mexican naturalized/documented | 5.15 * | 4.74 * | 4.88* | 3.61 | 3.63 | 3.92 | 6.76 * |

| Mexican U.S. born | 7.45 ** | 5.40 * | 5.68 * | 2.40 | 2.40 | 3.35 | 8.94 ** |

| White U.S. born | 11.96 *** | 8.71 *** | 8.93 *** | 2.46 | 2.44 | 2.21 | 7.03 * |

| Black U.S. born | 8.43 ** | 9.52 ** | 9.85 ** | 4.81 | 4.64 | 6.30 | 9.97 * |

| Child/Mother/Family Characteristics | |||||||

| Child female | 0.74 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.78 |

| Mother’s education < high school | −6.03 *** | −0.95 | −0.95 | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.81 | 1.32 |

| Poor family | −6.40 *** | −1.76 | −1.74 | −0.88 | −0.83 | −0.55 | −0.95 |

| Single parent | −5.44 ** | −4.78 ** | −4.61 ** | −3.17 * | −3.16 | −2.93 | −2.46 |

| Number of children in household | −2.02 ** | −1.62 ** | −1.61 ** | −1.63 ** | −1.62 ** | −1.37 * | −1.16 * |

| Mother depressed | −2.01 | −2.14 | −1.68 | −1.64 | −1.34 | −1.20 | |

| Mother’s Passage Comprehension | 0.25 *** | 0.14 ** | 0.13 * | 0.11 * | 0.11 * | ||

| Learning materials in home | 4.31 *** | 2.29 * | 2.25 * | 1.59 | 1.59 | ||

| How often mother reads to child | 2.11 *** | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.20 | ||

| Attends center-based child care | 4.82 * | 0.96 | 0.56 | 0.80 | |||

| Neighborhood Characteristics | |||||||

| Concentrated Disadvantage | −4.00 *** | 0.31 | 0.45 | ||||

| Concentrated Affluence | 5.96 *** | 5.72 ** | 5.45 ** | ||||

| Immigrant Concentration | −3.74 *** | 2.91 * | 8.18 ** | ||||

| Cross-level Interactions | |||||||

| Mexican documented * immigrant | −3.25 | ||||||

| Mexican U.S. born * immigrant | −9.22 ** | ||||||

| White U.S. born * immigrant | −5.73 * | ||||||

| Black U.S. born * immigrant | −10.25 ** | ||||||

| ICC | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.54 |

| Log-likelihood | −1701 | −1691 | −1691 | −1685 | −1685 | −1677 | −1671 |

| Unweighted N=396 | |||||||

Data Source: Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey; 2000 decennial census

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001 (one-tailed test)

In addition to the combined ethnicity/immigration status variable, Model 1 in Table 2 includes key socioeconomic (mother’s education, poverty) and demographic (child gender, family structure, number of children in the household) covariates. Controlling for these variables has little effect on the overall pattern shown in the bivariate results; Mexican children with undocumented mothers have significantly lower emergent reading scores than their co-ethnic counterparts with documented/naturalized mothers and Mexican, white and black children with U.S.-born mothers. However, the coefficients for all groups except black children of U.S.-born mothers are attenuated. For example, the estimate for whites declines from 11.96 to 8.71. As regards the other variables, maternal education and poverty are nonsignificant in Model 1, but living in a single-parent family and with more children in the household are negatively related to children’s LWI scores. These patterns do not change when maternal depression is added in Model 2, and depression is not significantly associated with LWI scores.

Model 3 builds upon Model 2 by adding measures of the cognitive home environment. After inclusion of these variables, none of the group contrasts remain significant. Among the cognitive home environment measures, the mother’s PC score and the presence of learning materials are noteworthy predictors. These relationships remain the same with the addition of center-based child care in Model 4. In contrast to the bivariate level, center-based child care is not significant in Model 4, but its inclusion reduced the coefficient for family structure to nonsignificance (p=0.056).

The role of neighborhood context is addressed in Models 5 and 6. When the contextual measures are considered together to test for their direct effects on LWI scores in Model 5, both concentrated affluence and immigrant concentration are positively related to children’s reading skills. At the same time, neighborhood context matters in another way. Tests for cross-level interactions between each neighborhood variable and ethnicity/immigration status revealed a significant interaction for neighborhood immigrant concentration. This interaction is included in Model 6 and illustrated in Figure 1. At low levels of immigrant concentration, all groups have significantly higher test scores than Mexican children with undocumented mothers. At higher levels of immigrant concentration, these differences are greatly reduced. Stated differently, immigrant concentration is positively related to LWI scores among Mexican children of undocumented mothers and negatively related to test scores among children of U.S. born mothers, regardless of ethnicity. Among Mexican children with foreign-born mothers, the association between immigrant concentration and LWI scores does not differ by the mother’s legal status. As is evident in Figure 1, Mexican children of undocumented mothers have consistently lower test scores than Mexican children with documented mothers, but the benefits associated with living among immigrants and Hispanics extend to both groups.

Figure 1.

Cross-level interaction between neighborhood immigrant concentration and mother’s ethnicity/immigration status, HLM model of Letter-Word Identification score

4.2.2. Applied problems

Table 3 provides a similar analysis for the Applied Problems (AP) test scores. In contrast to the previous results for the LWI test scores, the bivariate estimates indicate that Mexican children of undocumented and documented immigrant mothers do not differ with respect to emergent mathematics skills. Nonetheless the results are consistent with those for emergent reading skills in that all groups of children of U.S.-born mothers have higher test scores than Mexican children of undocumented mothers. The coefficient for white children is especially high at 20.64, or 1.4 standard deviations higher than the reference group. All other variables except for child sex and maternal depression are significantly related to children’s AP scores in the expected direction.

Table 3.

HLM Analysis of Woodcock Johnson Applied Problems Standard Scores, Ages 3–5

| Variable | Bivariate | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity/Mother’s Immigration Status | |||||||

| Mexican undocumented | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) |

| Mexican naturalized/documented | 4.11 | 3.51 | 3.41 | 2.29 | 2.34 | 2.65 | 6.04 |

| Mexican U.S. born | 7.78 ** | 5.71 * | 5.49 | 2.82 | 2.90 | 3.27 | 10.08 * |

| White U.S. born | 20.64 *** | 17.84 *** | 17.67 *** | 12.64 ** | 12.73 ** | 11.22 ** | 14.51 ** |

| Black U.S. born | 14.29 *** | 15.85 *** | 15.61 *** | 11.61 * | 11.64 * | 12.70 * | 17.79 ** |

| Child/Mother/Family Characteristics | |||||||

| Child female | 2.66 | 2.35 | 2.34 | 2.77 | 2.83 | 2.84 | 2.60 |

| Mother’s education < high school | −9.18 *** | 0.87 | 0.88 | 2.20 | 2.26 | 2.75 | 2.92 |

| Poor family | −10.67 *** | −4.64 * | −4.66 * | −4.17 * | −4.14 | −3.50 | −3.92 |

| Single parent | −7.85 *** | −5.87 ** | −6.00 ** | −4.78 * | −4.77 * | −4.31 * | −3.56 |

| Number of children in household | −2.28 * | −1.36 * | −1.37 * | −1.20 | −1.19 | −0.95 | −0.71 |

| Mother depressed | 1.84 | 1.55 | 1.95 | 1.99 | 2.38 | 2.81 | |

| Mother’s Passage Comprehension | 0.38 *** | 0.13 * | 0.12 * | 0.08 | 0.08 | ||

| Learning materials in home | 5.86 *** | 1.13 | 1.11 | 0.21 | 0.01 | ||

| How often mother reads to child | 3.03 *** | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.45 | ||

| Attends center-based child care | 6.80 * | 0.34 | −0.57 | −0.65 | |||

| Neighborhood Characteristics | |||||||

| Concentrated Disadvantage | −6.49 *** | −0.76 | −1.24 | ||||

| Concentrated Affluence | 9.41 *** | 4.85 * | 3.16 | ||||

| Immigrant Concentration | −7.38 *** | 0.98 | 7.75 * | ||||

| Cross-level Interactions | |||||||

| Mexican documented * immigrant | −3.96 | ||||||

| Mexican U.S. born * immigrant | −10.7 ** | ||||||

| White U.S. born * immigrant | −13.2 ** | ||||||

| Black U.S. born * immigrant | −12.7 ** | ||||||

| ICC | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.47 |

| Log-likelihood | −1819 | −1807 | −1807 | −1805 | −1804 | −1797 | −1791 |

| Unweighted N=396 | |||||||

Data Source: Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey; 2000 decennial census

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001 (one-tailed test)

Model 1 in Table 3 shows that the higher AP scores of Mexican, white and black children with U.S.-born mothers (relative to the reference group) cannot be explained by socioeconomic and demographic covariates. Yet, poverty, living in a single-parent household, and living in a household with a greater number of children are negatively associated with children’s AP test scores. These differences remain largely unchanged when maternal depression is added in Model 2, although the contrast between Mexican children with undocumented and U.S.-born mothers becomes nonsignificant. Maternal depression is not significant net of the included variables.

Model 3 adds measures of the cognitive home environment. The major patterns are unchanged except that the coefficients for children with U.S.-born mothers are attenuated. The mother’s cognitive (PC) score is the only significant predictor of children’s AP scores among the cognitive home environment variables. Children of mothers who score well on cognitive tests tend to do well themselves on tests that measure applied problems skills. Similarly, the addition of the indicator of participation in center-based child care (Model 4), which is nonsignificant, changes the model only slightly.

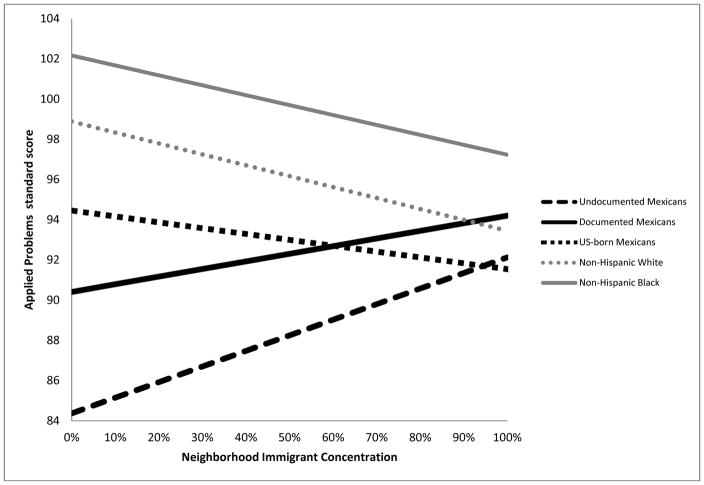

Models 5 and 6 provide insight into the role of the neighborhood context. Although children’s applied problems skills are higher across all groups when they live in an area of concentrated affluence (Model 5), the relationship between neighborhood immigrant concentration and children’s AP scores varies by ethnicity/immigration status (Model 6; illustrated in Figure 2). As was the case for children’s LWI scores, AP scores are higher among Mexican children with undocumented mothers when they live in a neighborhood characterized by high immigrant concentration. Residing in a neighborhood with high immigrant concentration does not similarly benefit children with U.S.-born mothers, regardless of their ethnicity. Again, the role of neighborhood immigrant concentration is similar for Mexican children of undocumented and documented immigrant mothers. Controlling for other variables in the model, including neighborhood disadvantage and affluence, group differences are largest at low levels of immigrant concentration.

Figure 2.

Cross-level interaction between neighborhood immigrant concentration and mother’s ethnicity/immigration status, HLM model of Applied Problems score

5. Discussion

The overall goal of this study was to provide new insights into the role of parental legal status in Mexican-origin children’s early cognitive skill development. Prior studies have drawn attention to this issue, but their conclusions are tentative due to an inability to separate differences in children’s cognitive achievement by parental nativity from differences by parental documentation status. This shortcoming is widely recognized, as is suggested by calls for measurement of the legal status of immigrant parents from direct questions (Yoshikawa and Kalil, 2011). We have responded to this call with the analysis of a survey administered to a representative sample of Los Angeles residents that permits the direct measurement of legal status.

The primary issue addressed here was whether (and how) the cognitive skills of young Mexican children differ by maternal nativity and documentation status. We also made comparisons with white and black children of U.S.-born mothers for additional benchmarks. Overall, the analysis showed that emergent reading skills—but not emergent mathematics skills—are significantly higher for Mexican children of documented versus undocumented mothers. In contrast, both types of scores are higher for children with U.S.-born mothers (regardless of ethnicity) than for those with undocumented mothers.

Drawing on research that emphasizes the importance of family socioeconomic status, the home environment, and the neighborhood context for cognitive development, we examined these disparities in a multivariate framework. Results from multilevel models suggest that early reading skill disparities are better explained by the socioeconomic, demographic, and home environment variables than early mathematics skill disparities. In fact, the emergent reading skill disparities were fully explained by these variables, with the number of children in the household, the mother’s passage comprehension score, and the learning materials in the home playing the largest role. This was not the case for applied problem-solving skills, where the test score advantage of white and black children of native-born mothers persisted across all models.

The inclusion of neighborhood characteristics (concentrated disadvantage, concentrated affluence, and immigrant concentration) did not change the basic patterns of cognitive skill disparities across groups. However, cross-level interaction tests revealed that the influence of neighborhood immigrant concentration varies across groups. Immigrant concentration is positively associated with early reading and mathematics test scores among Mexican children of both undocumented and documented immigrants, but is not similarly protective of children with U.S.-born parents. This is inconsistent with theories that emphasize the overwhelmingly negative impact of living in neighborhoods with large concentrations of disadvantaged immigrants, and consistent with the idea that immigrant enclaves can benefit immigrants and their children (Portes and Rumbaut, 2001).

The present study cannot ascertain the specific mechanisms through which neighborhood immigrant concentration shapes children’s test scores, but it seems most likely that the influence is indirect through parental well-being for pre-school children (Sastry and Pebley, 2010). Immigrant parents in co-ethnic environments may be able to access community resources tailored to their needs or form stronger social ties than immigrants in neighborhoods with low levels of immigrant concentration. They may thereby have greater social support, be less stressed, and be more able to engage in effective parenting than immigrants in environments that leave them more isolated. A potentially fruitful topic for future research is how the day-to-day experiences of immigrants and their children are influenced by the neighborhood and community contexts (Waters and Pineau, 2015). This work may require new data collection efforts that are designed to provide rich information on social networks and involvement in community institutions.

Homing in on the question of whether parental legal status per se plays a role in young children’s cognitive development requires a more singular focus on children of foreign-born mothers. As noted, maternal legal status matters for Mexican-origin children’s early reading skills, but not for their emergent mathematics skills. Children of undocumented mothers experience a constellation of risk factors that play a role in this pattern. First, undocumented mothers have very low levels of education: four of every five do not have a high school degree. This largely reflects education received in the home country, as 88% of the undocumented Mexican mothers in our sample never attended school in the United States. 6 This very low level of education underlies undocumented mothers’ relatively low passage comprehension test scores, which in turn have implications for the verbal stimulation in the home. Overall, these patterns reinforce the conclusion that immigrant parents’ pre-migration characteristics play an important role in their children’s outcomes in the destination society (Pong and Landale, 2012; Suárez-Orozco, Yoshikawa and Tseng, 2015). Although both documented and undocumented Mexican immigrants are disadvantaged, those without authorization to live in the United States are less advantaged upon arrival and have fewer opportunities to advance than those who are documented.

In summary, this research has provided new insights into the early development of a growing segment of the child population—Mexican-origin children with undocumented parents. While our findings suggest that it is not parental documentation status per se that accounts for the relatively low cognitive test scores of these children, further research on other domains of child development and other age groups is needed to illuminate how this understudied aspect of the immigrant experience affects the outcomes of children with immigrant parents.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) through grant 5P01HD062498-05 and R24HD041025. NICHD provided salary support to Dr. Landale, Dr. Oropesa, and Dr. Hillemeier. The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funding agency.

Footnotes

For ease of presentation, non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks are referred to as whites and blacks throughout this article.

Preliminary analyses included a parenting strain scale based on the level of agreement with four statements: “Being a parent is harder than I thought it would be,” “I feel trapped by my responsibilities as a parent,” “I find that taking care of my child/children is much more work than pleasure,” and “I often feel tired, worn out, or exhausted from raising a family” (Carpiano and Kimbro, 2012). The scores on this scale did not differ across the subgroups and the variable was nonsignificant in all models. We therefore omitted it from further analysis.

In preliminary models, we also considered multiple measures related to language: the language of test administration (Spanish versus English) for the child and his/her mother, household language, and linguistic isolation. Regardless of model specification, these variables were not significant and were therefore dropped from the analysis. We also assessed whether children in Spanish-only households who took the test in English scored lower than children who took the test in the language spoken in the home. This variable was also nonsignificant. For a detailed analysis of the role of language of test administration in Woodcock Johnson achievement test scores among children of Hispanic immigrants, see Akresh and Akresh (2011). Using unique data from the New Immigrant Survey in which the test language (Spanish versus English) was randomly assigned, their analysis of 3- to 12-year old children’s test scores shows rapid assimilation of English, even among foreign-born children.

We tested for multi-collinearity using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) (Scott, Simonoff, and Marx, 2013). In the models for both Letter-Word Identification (LWI) scores and Applied Problems (AP) scores, the VIF values for all variables were well below the commonly used cutoff of 10 (O’Brien, 2007).

Since the dependent variable is a standardized score with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15, the magnitude of the coefficients can be understood in terms of standard deviation units. For example, the unadjusted difference in LWI test scores between Mexican children with undocumented mothers and their counterparts with documented mothers is about one-third of a standard deviation (5.15/15). Mexican children of U.S.-born mothers score about one-half of a standard deviation (7.45/15) higher than children with undocumented mothers.

About 46% of the undocumented mothers had lived in the United States for less than 10 years, compared to 15% of the documented mothers. Even so, mother’s duration of residence in the United States was not a significant predictor of children’s letter-word identification or applied problems test scores.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

R.S. Oropesa, Email: rso1@psu.edu.

Aggie J. Noah, Email: ajn164@psu.edu.

Marianne M. Hillemeier, Email: mmh18@psu.edu.

References

- Akresh Richard, Akresh Ilana Redstone. Using Achievement Tests to Measure Language Assimilation and Language Bias among the Children of Immigrants. The Journal of Human Resources. 2011;46:647–667. [Google Scholar]

- Anger Steve, Heineck Guido. Do Smart Parents Raise Smart Children? The Intergenerational Transmission of Cognitive Abilities. Journal of Population Economics. 2010;23:1255–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmeier James D, Van Hook Jennifer, Bean Frank D. Can We Measure Immigrants’ Legal Status? Lessons from Two Surveys. International Migration Review. 2014;48:538–566. doi: 10.1111/imre.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein Marc H, Bradley Robert H. Socioeconomic Status, Parenting, and Child Development. New York: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley Robert H, Whiteside Leanne, Caldwell Bettye M, Casey Patrick H, Kelleher Kelly, Pope Sandra, Swanson Mark, Barrett Kathleen, Cross David. Maternal IQ, the Home Environment, and Child IQ in Low Birthweight, Premature Children. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1993;16(1):61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Soller B, Gardner M, Brooks-Gunn J. Feeling Disorder” as a Comparative and Contingent Process: Gender, Neighborhood Conditions, and Adolescent Mental Health. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 2013;54(3):296–314. doi: 10.1177/0022146513498510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano Richard M, Kimbro Rachael T. Neighborhood Social Capital, Parenting Strain, and Personal Mastery among Female Primary Caregivers of Children. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2012;52:232–247. doi: 10.1177/0022146512445899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger KJ, Rueter MA, Conger RD. The Role of Economic Pressure in the Lives of Parents and their Adolescents: The Family Stress Model. In: Crockett LJ, Silbereisen RK, editors. Negotiating Adolescence in Times of Social Change. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 201–223. [Google Scholar]

- Crane Jonathan. Effects of Home Environment, SES, and Maternal Test Scores on Mathematics Achievement. The Journal of Educational Research. 1996;89:305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha Flavio, Heckman James. The Technology of Skill Formation. The American Economic Review. 2007;97(2):31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Currie Janet, Thomas Duncan. Race, Children’s Cognitive Achievement, and the Bell Curve. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 5240 1995 [Google Scholar]

- Duncan Greg J, Dowsett Chantelle J, Claessens Amy, Magnuson Katherine, Huston Aletha C, Klebanov Pamela, Pagani Linda S, Feinstein Leon, Engel Mimi, Brooks-Gunn Jeanne, Sexton Holly, Duckworth Kathryn, Japel Crista. School Readiness and Later Achievement. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1428–1446. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan Greg J, Murane Richard. The Crisis of Inequality and the Challenge for American Education. Cambridge, MA and New York, NY: Harvard Education Press and Russell Sage Foundation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle Doris J, Alexander Karl L. The First Grade Transition in Life Course Perspective. In: Mortimer Jeylan, Shanahan Michael., editors. Handbook of the Life Course. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2002. pp. 229–250. [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW. The Environment of Childhood Poverty. American Psychologist. 2004;59:77–92. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas George. The Black-White Test Score Gap. Contexts. 2004;3(2):12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher Claude S, Hout Michael, Jankowski Martín Sánchez, Lucas Samuel R, Swidler Ann, Voss Kim. Inequality by Design: Cracking the Bell Curve Myth. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Flippen CA. Laboring Underground: The Employment Patterns of Hispanic Immigrant Men in Durham, NC. Social Problems. 2012;59:21–42. doi: 10.1525/sp.2012.59.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey William H. State of Metropolitan America: Race and Ethnicity. Brookings; 2011. America’s Diverse Future: Initial Glimpses at the U.S. Child Population from the 2010 Census. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller Bruce, Bridges Margaret, Bein Edward, Jang Heeju, Jung Sunyoung, Rabe-Hesketh Sophia, Halfon Neal, Kuo Alice. The Health and Cognitive Growth of Latino Toddlers: At Risk or Immigrant Paradox? Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2009;13:755–768. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0475-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Emma. Inequalities at the Starting Gate: Cognitive and Noncognitive Skill Gaps between 2010–2011 Kindergarten Classmates. Economic Policy Institute Report. 2015 Jun 17; [Google Scholar]

- Glick JE. Connecting Complex Processes: A Decade of Research on Immigrant Families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:498–515. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero Alma D, Fuller Bruce, Chu Lynna, Kim Anthony, Franke Todd, Bridges Margaret, Kuo Alice. Early Growth of Mexican–American Children: Lagging in Preliteracy Skills but not Social Development. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2013;7:1701–1711. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall Matthew, Greenman Emily, Farkas George. Wage Disparities for Mexican Immigrants in Low-Skill Labor Markets. Social Forces. 2010;89(2):491–513. doi: 10.1353/sof.2010.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall Matthew, Greenman Emily. Housing and Neighborhood Quality among Mexican and Central American Immigrants. Social Science Research. 2013;42:1712–1725. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernstein Richard J, Murray Charles. The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life. New York: The Free Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau Annette. Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal Tama, Shuey Elizabeth A. Neighborhood Context and Immigrant Young Children’s Development. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50:1771–1787. doi: 10.1037/a0036424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie Vivian. Keeping the Immigrant Bargain: The Costs and Rewards of Success in America. New York: The Russell Sage Foundation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Gentsch Kerstin. Undocumented Migration to the United States and the Wages of Mexican Immigrants. International Migration Review. 2014;48:482–499. doi: 10.1111/imre.12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrew Kevin S, Woodcock Richard W. Woodcock-Johnson III. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing; 2001. Technical Manual. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Childcare Research Network. Early Child Care and Children’s Development in the Primary Grades: Follow-up Results from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care. American Educational Research Journal. 2005;42:537–570. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett Richard E, Aaronson Joshua, Blair Clancy, Dickens William, Flynn James, Halpern Diane F, Turkheimer Eric. Intelligence: New Findings and Theoretical Developments. American Psychologist. 2012;67:130–159. doi: 10.1037/a0026699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwosu Chiamaka, Batalova Jeanne, Auclair Gregory. Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States. [Accessed September 19, 2011];Migration Information Source. 2014 Apr 28; ( http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states)

- O’Brien RM. A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors. Quality & Quantity. 2007;41(5):673–690. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla Yolanda C, Hummer Robert A, Boardman Jason, Espitia Marilyn. Is the Mexican American ‘Epidemiological Paradox’ Advantage at Birth Maintained Through Early Childhood? Social Forces. 2002;80:1101–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Passel Jeffrey S, Cohn D’Vera. Unauthorized Immigrant Population: National and State Trends, 2010. Pew Hispanic Center; 2011. [Accessed April 11, 2014]. ( http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/reports/133.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Peterson Christine E, Sastry Narayan, Pebley Anne R, Ghosh-Dastidar Bonnie, Williamson Stephanie, Lara-Cinisomo Sandraluz. The Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey Codebook. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pong Suet-ling, Landale Nancy S. Academic Achievement of Legal Immigrants’ Children: The Roles of Parents’ Pre- and Post-migration Characteristics in Origin-group Differences. Child Development. 2012;83(5):1543–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01790.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro, Rumbaut Rubén G. Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush Stephen W, Bryk Anthony S. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Romero VC. Everyday Law for Immigrants. Boulder, CO: Paradigm; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin Donald B. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson Robert J, Morenoff Jeff D, Gannon-Rowley Thomas. Assessing “Neighborhood Effects”: Social Processes and New Directions in Research. American Review of Sociology. 2002;28:443–478. [Google Scholar]

- Sastry Narayan, Pebley Anne R. Family and Neighborhood Sources of Socioeconomic Inequality in Children’s Achievement. Demography. 2010;47:777–800. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott Marc A, Simonoff Jeffrey S, Marx Brian D., editors. The SAGE Handbook of Multilevel Modeling. London: Sage Publications LTD; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco Carola, Yoshikawa Hirokazu, Tseng Vivian. A William T. Grant Foundation Inequality Paper. 2015. Intersecting Inequalities: Research to Reduce Inequality for Immigrant-Origin Children and Youth. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement, 2012. 2013. Internet release date: December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes Edna A, Schulz Amy J. Toward a Dynamic Conceptualization of Social Ties and Context: Implications for Understanding Immigrant and Latino Health. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:2167–2175. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.158956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes Edna A, Morenoff Jeffrey D, Williams David R, House James S. Contextualizing Nativity Status, Social Ties, and Ethnic Enclaves: Implications for Understanding Immigrant and Latino Health Paradoxes. Ethnicity & Health. 2013;6:586–609. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2013.814763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa Hirokazu. Immigrants Raising Citizens: Undocumented Parents and their Young Children. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa Hirokazu, Kalil Ariel. The Effects of Parental Undocumented Status on the Developmental Contexts of Young Children in Immigrant Families. Child Development Perspectives. 2011;5:291–297. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa Hirokazu, Kholoptseva Jenya. Unauthorized Immigrant Parents and Their Children’s Development: A Summary of the Evidence. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Waters Mary C, Pineau Marisa Gerstein., editors. The Integration of Immigrants into American Society. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- West Brady T, Welch Kathleen B, Galecki Andrzej T. Linear Mixed Models: A Practical Guide Using Statistical Software. CRC Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]