Abstract

Purpose of the Study:

Recent evidence shows that engaging in learning new skills improves episodic memory in older adults. In this study, older adults who were computer novices were trained to use a tablet computer and associated software applications. We hypothesize that sustained engagement in this mentally challenging training would yield a dual benefit of improved cognition and enhancement of everyday function by introducing useful skills.

Design and Methods:

A total of 54 older adults (age 60-90) committed 15 hr/week for 3 months. Eighteen participants received extensive iPad training, learning a broad range of practical applications. The iPad group was compared with 2 separate controls: a Placebo group that engaged in passive tasks requiring little new learning; and a Social group that had regular social interaction, but no active skill acquisition. All participants completed the same cognitive battery pre- and post-engagement.

Results:

Compared with both controls, the iPad group showed greater improvements in episodic memory and processing speed but did not differ in mental control or visuospatial processing.

Implications:

iPad training improved cognition relative to engaging in social or nonchallenging activities. Mastering relevant technological devices have the added advantage of providing older adults with technological skills useful in facilitating everyday activities (e.g., banking). This work informs the selection of targeted activities for future interventions and community programs.

Keywords: Cognitive intervention, Engagement, Cognitive training, Cognitive aging, Technology, iPad

As the proportion of older adults increases in society, it is of increasing economic and social importance to understand how to maintain the health of the aging mind. In 2010, the Alzheimer’s Association reported that an intervention that delays progression toward Alzheimer’s disease by five years would reduce the rate of national diagnosis by nearly 45%, resulting in very significant health and financial benefits (Alzheimer’s Association, 2010). Although both cognitive training (e.g., Anguera et al., 2013; Basak, Boot, Voss, & Kramer, 2008; Schmiedek, Lovden, & Lindenberger, 2010) and engaging in cognitively challenging activities (e.g., Carlson et al., 2008; Stine-Morrow, Parisi, Morrow, & Park, 2008; Tranter & Koutstaal, 2008) have been linked to cognitive improvement, most of the research to date has focused on cognitive training. Cognitive training and lifestyle engagement have differing approaches to cognitive facilitation: cognitive training targets specific domains with the expectation that improvements will be observed in that domain, and potentially transfer to other cognitive tasks and domains. In contrast, cognitive engagement interventions rely on the stimulation provided by activities that are novel for an individual and are broadly demanding of executive function, episodic memory, and reasoning (Park, Gutchess, Meade, & Stine-Morrow, 2007).

One reason for the limited research on engagement compared with cognitive training has been the cost and complexity of testing participants for prolonged periods in experimentally controlled real-world environments. Additionally, it is difficult to randomly assign participants to different experimental conditions not of their choosing and retain them over prolonged periods of time. Nevertheless, it is critical that we begin to understand what types and amounts of activities constitute “healthy behavior for the mind,” particularly given the urgency of the problem as baby boomers are reaching old age.

The notion that cognitive engagement is protective or supportive of cognition with age is supported by evidence that individuals who report high participation in mentally stimulating activities (e.g., reading, chess) show less age-related cognitive decline (Wilson et al., 2003, 2005) and have a decreased risk of Alzheimer’s disease than those who participate less (Wilson, Scherr, Schneider, Tang, & Bennett, 2007). However, it is difficult to disentangle causal relationships in these studies. It is not clear whether engagement enhances cognition or alternatively, if individuals who are cognitively healthy engage in activities that are more cognitively demanding. There are only a few studies that have attempted to disentangle this issue by experimentally manipulating engagement level. For example, Tranter and Koutstaal (2008) introduced a group of older adults between the ages of 60 and 75 years to a wide range of mentally stimulating activities that involved social group meetings, reading, music, and problem solving. They found that, when compared with a control group, the experimental group showed greater gains on a measure of fluid intelligence, suggesting that engaging in mentally stimulating activities for a short period is indeed beneficial to cognition.

In a study by Stine-Morrow and colleagues (2008), older adults participated in the Senior Odyssey program, which fostered an engaged lifestyle for 20 weeks by facilitating team-based problem-solving competitions that relied on cognitive processes such as working memory, processing speed, visuospatial processing, and reasoning in a community setting. When compared with a control group, participants in the program showed improvement on a composite measure of fluid cognitive ability. Another program, Experience Corps, had older adults partner with elementary school students, to whom they taught literacy skills, library support, and classroom etiquette (Carlson et al., 2008). Not only could the older adults benefit from the newly established relationships with students, but they also evidenced improvements in executive functioning and memory. Both Senior Odyssey and Experience Corps are community-based programs that include the potential for social, personal, and cognitive benefits, and thus have the potential to enrich lives as well as enhance cognitive function.

Most recently, Park and colleagues (2013) had older adults participate in cognitively demanding leisure activities such as learning to quilt and learning digital photography for 15hr a week for more than three months. The study (referred to later in this article as the “Synapse Project”) was based on a theoretical distinction between “productive” and “receptive” engagement (Park et al., 2007). Productive engagement involves activities that require significant cognitive challenge and self-initiated processing, resulting in sustained activation of working memory, episodic memory, and reasoning. For example, learning new computer software, learning a new language, or engaging in acquiring dance routines would be productive engagement. Park and Reuter-Lorenz (2009) have proposed that engagement in such active mental challenge for a sustained period promotes the formation of “neural scaffolds,” that is, supportive neural circuitry that provides a source of additional neural resource compensating for age-related brain shrinkage and neural degradation. There is a large literature suggesting that older adults indeed show such compensatory neural activity compared with young, particularly in frontal cortex (e.g., Gutchess et al., 2005). Although this study does not include brain imaging, the scaffolding model provides a strong conceptual framework for understanding the mechanism that operates when productive engagement improves cognition.

The Synapse Project (Park et al., 2013) had three productive engagement groups: learning to quilt, learning digital photography, or learning a combination of both. In contrast to productive engagement, receptive engagement involves activities that rely on existing knowledge and familiar activities that have low knowledge acquisition demands, such as completing word stems or playing games of chance. The Synapse Project had two receptive engagement groups: a Placebo group, where participants worked alone on activities low on working memory and episodic memory demand by doing tasks that required only knowledge or low cognitive effort; and a Social group that engaged in social, group-based activities but no formal learning or training. At the end of the three-month Synapse Project intervention, the three productive groups showed significant improvement in episodic memory relative to the receptive groups (Park et al., 2013), providing experimental evidence for this theoretical distinction.

This Study

As noted, there are few studies of engagement and cognition in older adults. In this study, we focused on the impact of training older adults in a novel technology that required sustained cognitive challenge to further test the hypothesis that productive engagement enhances cognitive function in older adults. Specifically, older adults who were computer novices were trained to become proficient users of a tablet computer using the iPad, which can be flexibly employed to perform many tasks associated with daily living. Training in new technology was chosen because mastery in technology among older adults has been shown to increase independence in old age and improve perceived life quality (e.g., Czaja, Guerrier, Nair, & Landauer, 1993; Mynatt & Rogers, 2001). Therefore, the goal of the iPad intervention was to investigate a novel form of engagement not previously studied in the literature that had high cognitive demands. Given the scant literature that exists, we wanted to determine if a qualitatively different task from those studied earlier, that nevertheless met the criteria for productive engagement, would show facilitation effects relative to receptive engagement conditions. In addition, iPad training had the added advantage of providing older adults with new ways to accomplish tasks that are relevant for maintaining independence in older adulthood, such as shopping, banking, communication, and securing medical care. Specifically, the wide range of available software applications (apps) for the iPad and their diverse uses provides a nearly endless way for older adults not only to learn challenging new activities, but to tailor the learning to an individual’s real-life needs. The portability and usability (e.g., touch screen, adjustable font, or icon size) of tablet computers provide easy access to computer technology for older adults who have a wide range of motor and visual abilities.

In this study, we recruited participants with little or no computer experience to commit at least 15hr each week to a combination of group classes, homework assignments, and other activities using the iPad. Participants were exposed to a structured curriculum for 5hr each week in a learning environment with a highly knowledgeable instructor and were required to spend an additional minimum of 10hr each week working on detailed assignments related to the weekly curriculum. The intervention required these novice users who were learning this new technology to engage in sustained activation of reasoning, executive function, and memory with a new task or learning challenge presented as soon as a particular skill was mastered.

We designed the iPad activity schedule to mirror the structure of activities from the Synapse Project, which, as noted earlier, included digital photography, quilting, social, and placebo groups (Park et al., 2013). Because of the cost and time demand inherent in engagement intervention studies, data from the two receptive engagement groups (Social and Placebo) in Park et al., 2013, were also used in this study as comparison control groups (see Methods section). The dual use of the receptive groups was planned a priori for both this study as well as for the Synapse Project (Park et al., 2013).

Methods

Participants

The full sample across the three conditions (iPad and two control groups) consisted of 54 older adults. Eighteen of these participants comprised the iPad intervention group, and there were 18 participants included from each of the Synapse control groups, which were matched on age, education, and gender to the iPad participants. All participants were community dwelling and were between the ages of 60 and 90 years with a high school education or greater. In addition, the participants were fluent in English, spent less than 10hr a week outside the home on volunteer or work activities, and also had limited experience with computers and no experience with tablet computers. Additional eligibility requirements included a minimum score of 20/40 on the Snellen eye chart (Snellen, 1863) after correction, a score of 26 or greater on the Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975), and no history of major psychiatric or neurologic disorders.

Recruitment

The participants for the iPad intervention were recruited simultaneously with the Synapse Project. An eligible applicant for both projects was randomly assigned to either the iPad intervention or the Synapse Project. The Synapse Project was a very large intervention with more than 250 participants and six different experimental groups, and had been an ongoing project for almost three years when the iPad intervention was initiated in 2011. As noted earlier, the iPad intervention was designed with a nearly identical structure to the Synapse groups, which allowed control participants in Synapse to also serve as control participants for the iPad intervention. Importantly, the recruitment procedures and screening criteria were the same across the two studies. Recruitment was conducted via advertisements, mass mailings, and community postings. All participants attended an enrollment meeting where details of the study were explained and the requirement of random assignment to conditions was explained to them.

Participants communicated freely with one another within each of the three study groups, but had no communication or exposure across groups. Since the Synapse Project was designed to be a much larger project than the iPad intervention, there were more participants in the Synapse control groups than in the iPad intervention. There were 39 participants in the original Synapse Placebo control condition and 36 in the Synapse Social control condition compared with the 18 participants in the iPad intervention. To equate the numbers for the three groups, the 18 participants from the iPad intervention who completed the program were matched on age, education, and gender to 18 participants from the Social and Placebo control conditions in the Synapse Project (Park et al., 2013). Participants for the three resulting groups did not differ in their demographic characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Information

| Total | iPad | Placebo | Social | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 54 | 18 | 18 | 18 | — |

| Age | 74.74 (6.13) | 74.89 (6.49) | 74.50 (5.79) | 74.83 (6.44) | ns |

| Years of education | 15.63 (2.40) | 15.28 (2.67) | 15.44 (2.31) | 16.17 (2.23) | ns |

| Female, % | 79.6 | 72.2 | 83.3 | 83.3 | ns |

| Minority, % | 18.5 | 27.8 | 16.7 | 11.1 | ns |

| Total program hours | — | 219.88 (27.58) | 226.22 (28.04) | 226.97 (24.92) | ns |

Note: Mean differences were tested with analysis of variance for continuous variables, and with Chi-square tests for categorical variables. Standard deviation is in parentheses. ns = not significant.

Attrition

Of the original 25 participants who were recruited for the iPad intervention, 7 participants failed to complete the full intervention and posttesting: 6 dropped out due to serious health or personal issues (e.g., new diagnosis of cancer, seriously ill spouse) and 1 was excluded due to insufficient hours logged in the program despite reminders. Those who dropped out did not significantly differ from the retained sample in age (t = 1.043, p = .315) and education (t = −0.451, p = .664). Note that those who dropped out were not from a specific age group (age range = 67–80 years) or education level (education in years range = 13–18). Of the original Synapse participants in the Placebo condition, all participants were retained. For the Social condition, 12 dropped out, and of those, 7 of them withdrew from the study due to health reasons, and 5 due to an inability to commit enough time.

Study Overview

The iPad intervention program consisted of planned activities that required continuous cognitive challenge by engaging novice tablet computer users in structured lessons and assignments, which involved constant new learning in the use of numerous applications for the device. In contrast, both the Placebo and Social group engaged in receptive activities that required no structured learning or training, and minimal cognitive challenge. The three conditions—the iPad, Placebo, and Social groups—are fully described in the Productive Engagement and Receptice Engagement Condition section below.

Productive Engagement Condition

iPad group

Participants attended a 10-week program, where they were required to spend at least 15hr each week learning a new set of skills associated with the iPad. This included two 2.5-hr training classes that were held at the Synapse site each week, while the remaining 10hr were spent working on homework assignments. All classes were taught by the same instructor and the activities followed a detailed curriculum. The instructor was available during business hours at the Synapse site and students could consult with the instructor as well as work with one another in the space. The first week of classes focused on learning the basic functions and navigation of the iPad (e.g., hardware controls, software settings, volume) and discovering the variety of apps available. Subsequent weeks were organized by theme, where participants learned the function and use of apps related to that theme for 1 week. For example, for one theme, “Connectivity and Social Networking,” participants learned how to “follow” each other on Twitter (Twitter Inc., 2012), upload photos, and play games that use social networks as platforms, such as Words with Friends (Zynga Inc., 2009). Another theme, “Health and Finance,” focused on having participants explore apps that could provide tips and resources on health and track different types of financial resources. Besides interacting with fellow participants in the iPad intervention, participants learned how they could use apps to connect with their grandchildren and friends as well. Throughout the program, participants chronicled their experiences with entries in journaling apps such as ScrapPad (Album tArt LLC, n.d.). To maintain participation and monitor program adherence, participants filled in a log documenting the amount of time they spent on the iPad each week. A detailed curriculum can be found in the Supplementary Appendix. The participants in the iPad intervention spent a mean total of 219.76hr over the 10-week period (standard deviation [SD] = 27.67), averaging considerably more than the 15hr per week minimum. The instructor was available to the participants all week during business hours, and participants frequently spent time working with the instructor and each other outside of training hours.

Receptive Engagement Conditions

Placebo group

Participants completed cognitive activities for 15hr per week that were low in cognitive demand, frequently relied on world knowledge, and involved no active skill acquisition. Activities included playing games of chance, watching movies, completing knowledge-based word puzzles, reading popular articles from informative magazines, and listening to classical music or to National Public Radio (NPR) shows. All activities were performed at home, so this group received minimal social stimulation. Participants in this condition came to the research site once a week and met with a group leader. They were assigned 5hr of activities from a “core curriculum” that were common to all participants in the Placebo group. Then, each participant selected 10 additional hours of similar activities from what we called the “brain library.” This library contained a wide variety of DVDs, CDs, and magazines that were comprised of five categories: humor (e.g., comedy DVD), learning (e.g., magazines), music (CDs), puzzles and games (e.g., crossword puzzles), and classic movies. Participants were told that the activities were designed to facilitate cognitive improvement with resources that were readily available (e.g., TV, radio, and the library). Participants logged the time they spent in a diary and also completed descriptive questions about the tasks they completed to verify compliance. We note that this group (and other groups from the Synapse Project) completed 12 weeks of participation and were then tested during Weeks 13 and 14. They spent a total of 226.22hr across the 12 weeks (SD = 28.04).

Social group

The Social group was designed to replicate the camaraderie and social interactions that occurred in a group learning setting such as that experienced by the iPad group, while excluding an active learning environment. Similar to the other two groups, the Social group was required to spend a minimum of 15hr in social activities, with 5hr prescribed for all, and 10 that were selected by participants. The prescribed activities were organized around weekly structured topics, such as travel, art, or history, and were heavily reliant on existing knowledge rather than learning new or novel information. Like the iPad group, participants in the Social group attended 2.5-hr structured sessions twice a week. These sessions involved discussion of the weekly topic and included sharing memories, stories, and possessions that were related to the topic, and sometimes a field trip to a local community facility related to the topic (e.g., art museum). In addition to the two weekly sessions, participants were given a list of activities to choose from each week and selected a minimum of 10hr in activities that were relatively low in cognitive demand and included things like recipe exchanges, covered dish luncheons, watching situation comedies together, and playing games with low level of cognitive challenge. The activities were designed to be respectful of the older adults’ maturity and function but minimized activities that had high working memory, reasoning, or episodic memory requirements (e.g., playing bridge or chess). Like the Placebo group, these participants had 12 weeks of participation and then were tested in Weeks 13 and 14. They spent a mean total of 226.97hr in the study (SD = 24.92).

We note here that although the iPad group had a 10-week intervention compared with the 12 weeks for the Placebo and Social group, the total hours spent during the entire program was comparable for both groups (iPad: M = 219.76, SD = 27.67; Placebo: M = 226.22, SD = 28.04; Social: M = 226.97, SD = 24.92). The difference in weeks was a result of constraints on space and the availability of the iPad instructor. Nevertheless, total time in the intervention was equated as participants in the iPad group spent more time per week for fewer weeks.

Cognitive Testing

All participants completed the same battery of cognitive and psychosocial testing both before and after the training period. The participants were compensated $100 for completing pretesting and $140 for completing posttesting. The assessment protocol was the same for pretest and posttest and, whenever possible, posttesting for each participant was administered by the same tester, on the same day of the week, and at the same time of day as their pretest session. Testing included both paper-and-pencil and computerized tasks. All computer tasks were conducted on Dell desktop computers running Windows XP, using a Wacom touch-screen monitor. Each testing session was conducted by a trained tester who was not involved in the intervention training and was blind to group assignment.

The tasks included in the analysis are organized by constructs that were derived from the original Synapse Project (Park et al., 2013), which had a large enough sample size to verify both construct reliability and test-retest reliability of the grouped cognitive measures. A summary of the four constructs and the tasks associated with them are as follows:

1. Processing speed was measured using the Digit Comparison Task (Salthouse & Babcock, 1991). Participants made same/different judgments in a fixed interval about digit strings. There were three levels of task difficulty, with number of correct comparisons at each level as indicators of the speed construct.

2. Mental control was measured using the Cogstate Identification Task (http://www.cogstate.com) and three modified versions of the Flanker task: Flanker Center Letter, Flanker Center Symbol, and Flanker Center Arrow (Eriksen & Eriksen, 1974). The Cogstate Identification Task measures attention and the three Flanker tasks measure the ability to suppress or inhibit attention to a salient feature of the presented stimuli.

3. Episodic memory was measured using the Modified Hopkins Verbal Learning Task (HVLT; Brandt, 1991) and the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) Verbal Recognition Memory (Robbins et al., 1994). For both tasks, participants studied lists of words. Three measures of recall were used as indicators of the construct (immediate recall from HVLT and CANTAB, and delayed 20-min recall from HVLT).

4. Visuospatial processing was measured by a shortened version of the Raven’s Progressive Matrices (Raven, Raven, & Court, 1998), CANTAB Stockings of Cambridge (Robbins et al., 1994), and CANTAB Spatial Working Memory (Robbins et al., 1994). The first two are measures of visuospatial reasoning and the third task measures visuospatial working memory.

Results

Overview of Analyses

The aim of the analyses was to determine whether cognitive performance, as a result of the iPad intervention, improved more from pretest to posttest than performance in the two control conditions (Social and Placebo).

Cognitive Constructs

To create the four cognitive constructs, we followed the procedures described in The Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly trial (Ball et al., 2002) by first creating a normalized distribution of the target dependent variables from each measure by pooling together pretest and posttest scores and then applying a rank-ordered Blom transformation (Blom, 1958). Then, a composite score for each construct was created by averaging the transformed scores associated with the appropriate construct measures. Cronbach’s alpha (α) was calculated to test the internal consistency of each construct, and all showed high consistency as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reliability for Cognitive Construct Measure

| Cognitive construct | Measure | Dependent variable | Composite reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Processing speed | Digit Comparison | Total correct on trials with three items | .86 |

| Total correct on trials with six items | |||

| Total correct on trials with nine items | |||

| Mental control | Cogstate Identification | Log RT to a 2-forced choice decision | .81 |

| Flanker Center Letter | RT for incongruent trials that follow congruent trials | ||

| Flanker Center Symbol | RT for incongruent trials that follow congruent trials | ||

| Flanker Center Arrow | RT for incongruent trials that follow congruent trials | ||

| Episodic memory | CANTAB Verbal Recall Memory | Total correct on immediate free recall | .75 |

| Hopkins Verbal Learning Task (HVLT; immediate) | Total correct on trials 1, 2, and 3 | ||

| Hopkins Verbal Learning Task (HVLT; delayed) | Total correct after a 20-min delay | ||

| Visuospatial processing | Modified Raven’s Progressive Matrices | Accuracy out of 18 items | .69 |

| CANTAB Stockings of Cambridge | Problems solved in the minimum amount of moves | ||

| CANTAB Spatial Working Memory | Between errorsa | ||

| Strategy scorea |

Notes: Composite reliabilities were calculated using Cronbach’s alpha (α).

aDenotes scores where higher scores reflect worse performance. RT = reaction time.

Intervention Analysis

Initial pretest performance of the three groups did not significantly differ across all four constructs, all F < 1.9, p = ns (see Table 3 for pretest analysis of variances [ANOVAs]). To evaluate the effects of the interventions on cognitive performance, we conducted a mixed ANOVA on each cognitive construct with Group as a between-subjects variable (iPad, Social, and Placebo) and Time (pretest or posttest) as the within-subject variable. After the overall mixed ANOVA was completed, additional follow-up testing was performed to further evaluate constructs, where a significant Group × Time interaction was observed. In addition to the ANOVAs, we calculated the net effect size of each of the intervention groups as conducted by Ball and colleagues (2002). Specifically, the net effect is represented by the gain in performance (from pretest to posttest) normalized by pretest sample variance using the following formula:

Table 3.

Pretest and Posttest Cognitive Construct Scores, and Pretest ANOVA

| Cognitive construct | Time | Groups | Pretest ANOVA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iPad | Placebo | Social | F | p | ||

| Processing speed | Pre | −0.065 (1.04) | 0.154 (0.801) | −0.088 (0.831) | 0.401 | .671 |

| Post | 0.205 (1.15) | 0.097 (0.718) | −0.201 (0.761) | |||

| Mental control | Pre | 0.066 (0.510) | 0.011 (0.880) | −0.076 (0.945) | 0.147 | .863 |

| Post | 0.111 (0.508) | 0.169 (0.885) | 0.241 (0.804) | |||

| Episodic memory | Pre | −0.258 (0.592) | 0.020 (0.945) | 0.238 (0.840) | 1.72 | .190 |

| Post | 0.397 (0.460) | 0.165 (0.826) | 0.471 (0.700) | |||

| Visuospatial processing | Pre | 0.231 (0.708) | −0.232 (0.684) | 0.013 (0.751) | 1.89 | .161 |

| Post | 0.415 (0.640) | 0.029 (0.730) | 0.064 (0.683) | |||

Note: Mean Blom-transformed score (SD). ANOVA = analysis of variance.

is the standard deviation at pretest, and and represent pre- and post-Blom transformation scores for the intervention groups, respectively. and represent pre- and post-Blom transformation scores for the control group, respectively.

Although no detectable differences were observed in pretest cognition scores, we further evaluated the impact of pretest scores on gains by conducting analysis of covariances (ANCOVAs), with cognitive change scores (pretest – posttest) as the dependent variable, groups as the between-subject variable, and the pretest score as the covariate. This allowed us to observe group differences in change score while controlling for cognition differences at pretest.

Results

The results yielded evidence for greater improvement over time in the iPad intervention compared with the control groups for processing speed and episodic memory. Specifically, the overall ANOVA on processing speed resulted in a main effect of Time (F(1,51) = 7.43, p = .009) and a Group × Time interaction (F(2,51) = 4.35, p = .018). Follow-up comparisons yielded evidence that the iPad group improved performance in processing speed more over time than both the Placebo group (F(1,34) = 5.80, p = .022) and the Social group (F(1,34) = 8.35, p = .007). We found similar significant effects for episodic memory, with a main effect of Time (F(1,51) = 42.23, p < .001) and a Group × Time interaction (F(2,51) = 7.31, p = .002). Again, the interaction was significant because the iPad group improved more over time than both the Placebo group (F(1,34) = 10.44, p = .003) and the Social group (F(1,34) = 12.22, p = .001). The Placebo group and Social group did not differ in their change over time in processing speed or episodic memory (F < 2.32, p = ns). These effects, except for processing speed between iPad and Placebo, remained significant after correcting for multiple comparisons with a Bonferroni correction. No significant effects were observed for the mental control or visuospatial processing constructs.

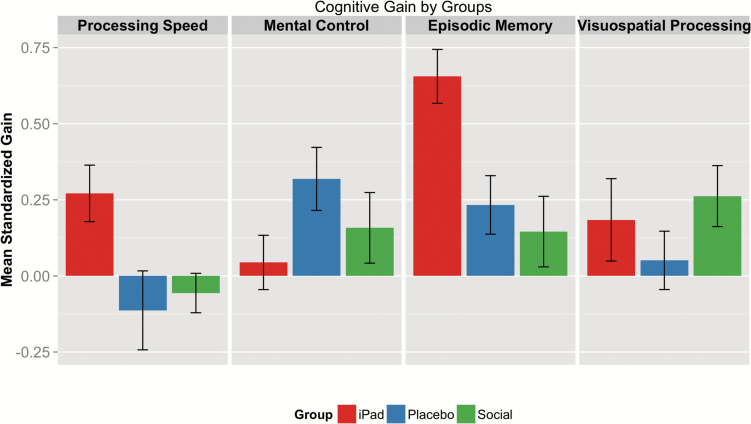

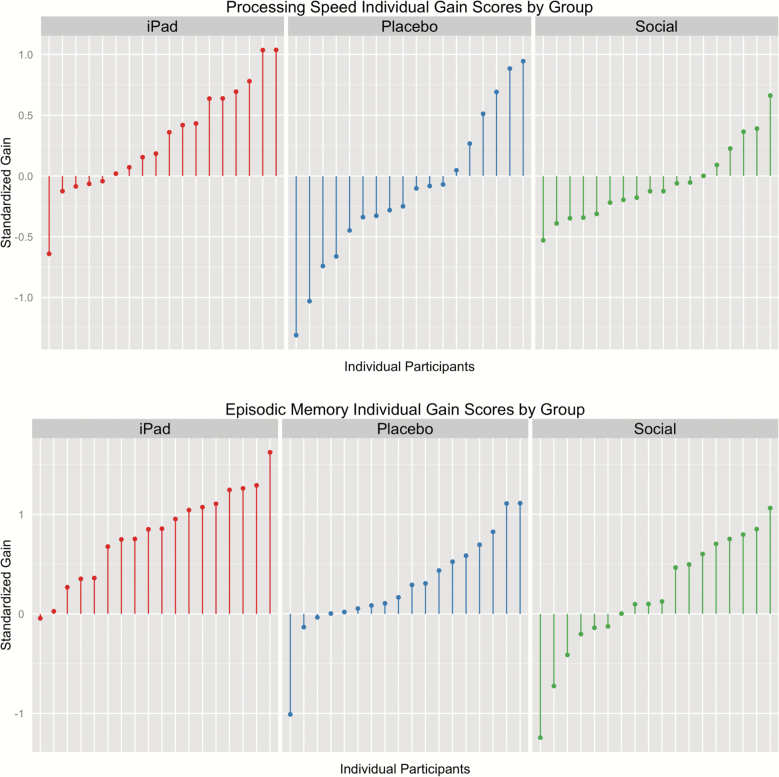

Supplementing the results from the ANOVAs, the net effect sizes associated with speed and episodic memory in the iPad group were congruent with the statistical results. The net effect sizes for the four constructs with the appropriate group contrasts (iPad vs. Placebo; iPad vs. Social; Placebo vs. Social) are reported in Table 4. The mean normalized gains scores of all four constructs between the three groups are shown in Figure 1. In addition, to further explicate the facilitation effects, that we observed in the iPad condition for processing speed and episodic memory, we present individual gain scores for each participant as a function of Group in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Net Effect Sizes of Cognitive Constructs

| Net effect sizes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive construct | iPad vs. Placebo | iPad vs. Social | Placebo vs. Social |

| Processing speed | .43 | .37 | −.06 |

| Mental control | −.35 | −.14 | .20 |

| Episodic memory | .52 | .62 | .11 |

| Visuospatial processing | .18 | −.11 | −.29 |

Note: Net effect sizes represent gain in performance (from pretest to posttest) normalized by pretest sample variance.

Figure 1.

Mean standardized gain scores for iPad, Placebo, and Social. Error bars: ±1 SE.

Figure 2.

Individual gain score (pretest adjusted to 0) for tasks with significant differences.

In a final analysis, ANCOVAs were performed for each cognitive construct with pretest score as the covariate. Like the earlier analysis, we found a significant effect for processing speed (F(2,50) = 4.34, p = .018) and episodic memory (F(2,50) = 6.279, p = .004), but not for mental control or visuospatial processing (F < 1.7, p = ns). These results confirmed that differences in pretest scores did not drive the observed Group × Time interactions we reported previously.

Discussion

The main finding from this study was that participation in the iPad intervention resulted in enhanced performance on two cognitive constructs—processing speed and episodic memory—compared with both a Social control and a Placebo control. The results showed that productive engagement, which requires sustained mental effort, is more supportive of two major cognitive constructs in older adults than receptive engagement, which consists of less cognitively demanding activities in which little new learning and skill acquisition takes place. Although some individuals in the two receptive control groups also experienced some cognitive improvements (Figure 2), the iPad group showed significantly more improvement over time. The increases in the control groups could be due to repeated testing effects, but it is also possible that the control intervention groups experienced slight cognitive enhancements.

In light of the large body of evidence that even healthy older adults experience age-related declines across multiple facets of cognition (Park & Shaw, 1992; Park et al., 1996; Salthouse, 1996; Salthouse & Babcock, 1991), one major goal of interventions is to improve or maintain cognition in order to promote independence and quality of life. The results of this study add to the sparse body of literature suggesting that engagement in mentally challenging everyday activities can be supportive of cognition. Specifically, previous studies such as Experience Corps (Carlson et al., 2008) and the Synapse Project (Park et al., 2013) have both found that older adults experience enhanced performance in memory post-intervention, which is also the strongest finding of this study. Importantly, this study was driven by the theoretical distinction of productive versus receptive engagement, which predicts that not all types of engagement are equally beneficial to cognition (Park et al., 2007). Interventions that rely on sustained cognitive challenge (and typically novelty) will be more facilitative than noncognitively challenging activities. Park and colleagues (2013) previously demonstrated two other forms of productive engagement—learning digital photography and/or quilting—were facilitative of enhanced episodic memory performance. The iPad intervention differed considerably in format and substance from quilting or photography, but had in common the requirement that individuals engage in considerable new learning, mental challenge, and self-initiated processing. One important direction for future research is to assess whether an increasing degree of cognitive challenge facilitates greater cognitive improvement. Some measures of rated difficulty of engaging activity or manipulation of load during engagement would be an important next step in evaluating the role of mental challenge in facilitating cognitive health.

Another direction or future research would be to determine whether engagement promotes neural scaffolding. As noted earlier, the Scaffolding Theory of Aging and Cognition (STAC) model (Park & Reuter-Lorenz, 2009) proposes that neural scaffolding—recruitment of additional neural circuits to compensate for declining brain structures—develops in response to continuous engagement associated with novel and cognitively challenging tasks. As an example, recent evidence demonstrated that older adults who experienced cognitive gains after video game training also showed more efficient neural function through enhancement of electroencephalography (EEG) signal in regions associated with cognitive control (Anguera et al., 2013). We recognize that more research is needed to confirm the underlying brain mechanisms that may facilitate cognitive improvements observed in this study, but note that the STAC model provides a theoretical framework for understanding cognitive changes that resulted from the engagement intervention. Future studies incorporating neuroimaging are likely to provide evidence of the mechanisms underlying enhancement effects associated with productive engagement.

Importantly, we note that programs similar to the iPad intervention, which focus on a broad lifestyle engagement approach, could be easily implemented in a community setting. In this study, participants met for group classes in a research site resembling a community center. The program not only consisted of a core curriculum organized by themes and related apps, but also encouraged participants to discover and interact with apps that were personally relevant. As shown in a recent evaluation of a community-based computer training program (Czaja, Lee, Branham, & Remis, 2012), the advantage of programs similar to iPad intervention is that it can be effectively implemented with community volunteers.

Finally, we note that the overall experience of those who participated in the iPad intervention was extremely positive, and, according to the postcompletion survey, all 18 participants obtained a tablet device after the completion of the program (either by purchase or as a gift). Therefore, facilitation effects could be maintained or enhanced following the iPad training; however, future research using longitudinal data from follow-up cognitive testing should be administered to quantify the long-term retention of benefits after the intervention.

Conclusion

In sum, the iPad intervention was designed to facilitate cognitive improvements and offer comprehensive training on a cutting-edge technology that could be easily implemented among community-dwelling older adults. Participants were able to access the wide variety of services and activities available through the apps, both during and after the completion of the program. Thus, the program was successful at improving cognitive performances through productive engagement and provided an added benefit of technological mastery.

Supplementary Material

Please visit the article online at http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institute on Aging (5R01AG026589-02): Active Interventions for the Aging Mind and National Institute on Aging American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) Administrative Supplement grant (RFA NOT-OD-09-056 to D. C. Park).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Katie Berglund, for serving as the training instructor in the project, and Michele Sauerbrei and Carol Fox for assisting her. The authors also thank Janice Gebhard, Whitley Aamodt, Carol Bardhoff, and Marcia Wood, for testing participants, and Joanne Pratt, for her assistance in project discussions and meetings.

References

- Album tArt LLC. (n.d.). ScrapPad - Scrapbook for iPad Retrieved from https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/scrappad-scrapbook-for-ipad/id353143273?mt=8

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2010). Changing the trajectory of Alzheimer’s disease: A national imperative. Chicago, IL: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Anguera J. A. Boccanfuso J. S. Rintoul J. L. Al-Hashimi O. Faraji F. Janowich J., …Gazzaley A (2013). Video game training enhances cognitive control in older adults. Nature, 501, 97–101. doi:10.1038/nature12486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K. Berch D. B. Helmers K. F. Jobe J. B. Leveck M. D. Marsiske M., … Willis S. L (2002). Effects of cognitive training interventions with older adults. Journal of the American Medical Association, 288, 2271–2281. doi:10.1001/jama.288.18.2271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basak C. Boot W. R. Voss M. W., & Kramer A. F (2008). Can training in a real-time strategy video game attenuate cognitive decline in older adults? Psychology and Aging, 23, 765–777. doi:10.1037/a0013494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom G. (1958). Statistical estimates and transformed beta-variables. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J. (1991). The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test: Development of a new memory test with six equivalent forms. Clinical Neuropsychologist, 5, 125–142. doi:10.1080/13854049108403297 [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M. C. Saczynski J. S. Rebok G. W. Seeman T. Glass T. A. McGill S., …Fried L. P (2008). Exploring the effects of an “everyday” activity program on executive function and memory in older adults: Experience Corps. The Gerontologist, 48, 793–801. doi:10.1093/geront/48.6.793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaja S. J. Guerrier J. H. Nair S. N., & Landauer T. K (1993). Computer communication as an aid to independence for older adults. Behaviour & Information Technology, 12, 197–207. doi:10.1080/01449299308924382 [Google Scholar]

- Czaja S. J. Lee C. C. Branham J., & Remis P (2012). OASIS connections: Results from an evaluation study. The Gerontologist, 52, 712–721. doi:10.1093/geront/gns004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen B. A., & Eriksen C. W (1974). Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Perception & Psychophysics, 16, 143–149. doi:10.3758/BF03203267 [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M. F., Folstein S. E., McHugh P. R. (1975). “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutchess A. H. Welsh R. C. Hedden T. Bangert A. Minear M. Liu L. L., & Park D. C (2005). Aging and the neural correlates of successful picture encoding: Frontal activations compensate for decreased medial-temporal activity. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 17, 84–96. doi:10.1162/0898929052880048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mynatt E. D., & Rogers W. A (2001). Developing technology to support the functional independence of older adults. Ageing International, 27, 24–41. doi:10.1007/s12126-001-1014-5 [Google Scholar]

- Park D. C., Gutchess A. H., Meade M. L., Stine-Morrow E. A. (2007). Improving cognitive function in older adults: Nontraditional approaches. The Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62, 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D. C. Lodi-Smith J. Drew L. Haber S. Hebrank A. Bischof G. N., & Aamodt W (2013). The impact of sustained engagement on cognitive function in older adults: The Synapse Project. Psychological Science, 25, 103–112. doi:10.1177/0956797613499592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D. C., Reuter-Lorenz P. (2009). The adaptive brain: Aging and neurocognitive scaffolding. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 173–196. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D. C., & Shaw R. J (1992). Effect of environmental support on implicit and explicit memory in younger and older adults. Psychology and Aging, 7, 632–642. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.7.4.632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D. C. Smith A. D. Lautenschlager G. Earles J. L. Frieske D. Zwahr M., & Gaines C. L (1996). Mediators of long-term memory performance across the life span. Psychology and Aging, 11, 621–637. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.11.4.621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven J. Raven J. C., & Court J. H (1998). Manual for Raven’s Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary Scale. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins T. W. James M. Owen A. M. Sahakian B. J. McInnes L., & Rabbitt P (1994). Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB): A factor analytic study of a large sample of normal elderly volunteers. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 5, 266–281. doi:10.1159/000106735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse T. A. (1996). The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychological Review, 103, 403–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse T. A., & Babcock R. L (1991). Decomposing adult age differences in working memory. Developmental Psychology, 27, 763–776. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.27.5.763 [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedek F. Lovden M., & Lindenberger U (2010). Hundred days of cognitive training enhance broad cognitive abilities in adulthood: Findings from the COGITO Study. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 2, 27. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2010.00027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snellen H. (1863). Probebuchstaben zur Bestimmung der Sehschaerfe. Utrecht, Netherlands: PW van de Weijer. [Google Scholar]

- Stine-Morrow E. A. L. Parisi J. M. Morrow D. G., & Park D. C (2008). The effects of an engaged lifestyle on cognitive vitality: A field experiment. Psychology and Aging, 23, 778–786. doi:10.1037/a0014341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranter L. J., & Koutstaal W (2008). Age and flexible thinking: An experimental demonstration of the beneficial effects of increased cognitively stimulating activity on fluid intelligence in healthy older adults. Neuropsychology, Development, and Cognition, 15, 184–207. doi:10.1080/13825580701322163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twitter Inc. (2012). Twitter (Version 4.1.3). Retrieved from https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/twitter/id333903271?mt=8 [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R. S. Barnes L. L. Krueger K. R. Hoganson G. Bienias J. L., & Bennett D. A (2005). Early and late life cognitive activity and cognitive systems in old age. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 1, 400–407. doi:10.1017/S1355617705050459 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R. S. Bennett D. A. Bienias J. L. Mendes De Leon C. F. Morris M. C., & Evans D. A (2003). Cognitive activity and cognitive decline in a biracial community population. Neurology, 61, 812–816. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000083989.44027.05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R. S. Scherr P. A. Schneider J. A. Tang Y., & Bennett D. A (2007). Relation of cognitive activity to risk of developing Alzheimer disease. Neurology, 69, 1911–1920. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000271087.67782.cb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zynga Inc. (2009). Words with Friends (Version 4.12). Retrieved from https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/words-with-friends-free/id321916506?mt=8

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.