Abstract

A 16-month-old intact female Maltese dog was referred for examination of depression and vomiting. Ultrasonography revealed dilated right renal pelvis containing echogenic fluid with free gas. A hyperechoic material suspected of urolith was identified in the right ureter. Computed tomography revealed emphysematous change of the right kidney associated with ureteral obstruction and extrahepatic portosystemic shunt (EHPSS). Ureteronephrectomy and surgical correction were performed for the EHPSS. Escherichia coli was isolated from pus from the right kidney. Quantitative analysis revealed that the urolith was an ammonium urate stone. After 5 months follow-up, no complication was observed. This is the first report of emphysematous pyonephrosis associated with EHPSS in a dog.

Keywords: ammonium urate, canine, portosystemic shunt, pyonephrosis

Pyonephrosis defined as infected hydronephrosis associated with suppurative destruction of the parenchyma of the kidney may cause septic shock [6, 18]. Almost all dogs with pyonephrosis have conspicuous obstruction in the renal collecting system [5, 13, 20]. Animals with portosystemic shunt (PSS) may show urinary tract signs. These signs can be associated with ureteral obstruction caused by ammonium urate ulolith and bacterial upper urinary tract infections (UTIs) [7, 14, 17]. Here, we report emphysematous pyonephrosis associated with PSS in a dog.

A 16-month-old intact female Maltese was referred for examination of depression and vomiting within an hour after eating high-protein food. Its rectal temperature was 39.8°C. No other abnormality was noted on physical examination. Complete blood cell counts (CBC) showed anemia (hematocrit 25%, reference 37–55%), leukocytosis (27.06 × 109/l, reference 0.6–17.0 × 109/l) and thrombocytopenia (134 × 109/l, reference 200–500 × 109/l). On biochemical profiling, the following abnormalities were noted: elevated alkaline phosphate (994 U/l, reference 20–150 U/l), hypoalbuminemia (1.8 g/dl, reference 2.5–4.4 g/dl) and hypoglycemia (38 mg/dl, reference 74–143 mg/dl). Serum urea nitrogen level and creatinine level were within the normal range. Serum bile acid (SBA) was elevated over 30 µmol/l on preprandial (reference 0.2–4.3 µmol/l) and two-hour postprandial (reference 0.6–24.2 µmol/l). Urinalysis showed proteinuria (protein level of 2+), glycosuria (glucose level of 1+) and normal urine specific gravity (1.025) with dipstick analysis. There were rod-shaped bacteria and neutrophils in the urine aspirated on sediment examination with Diff-Quick stain.

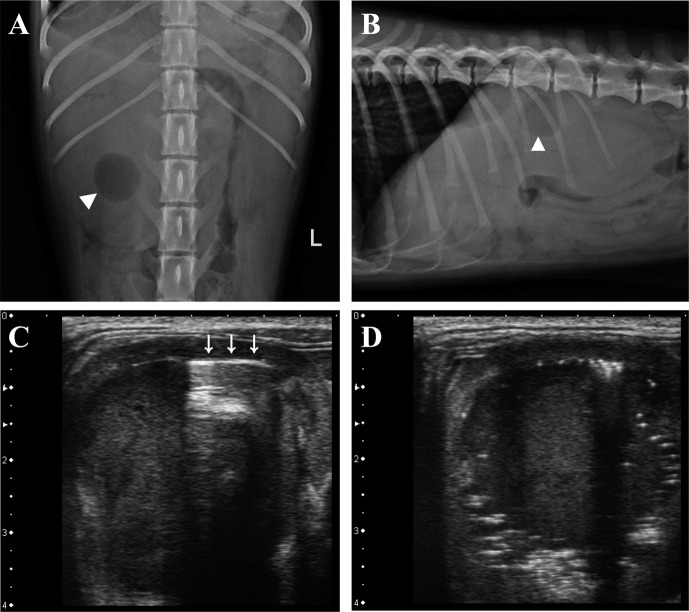

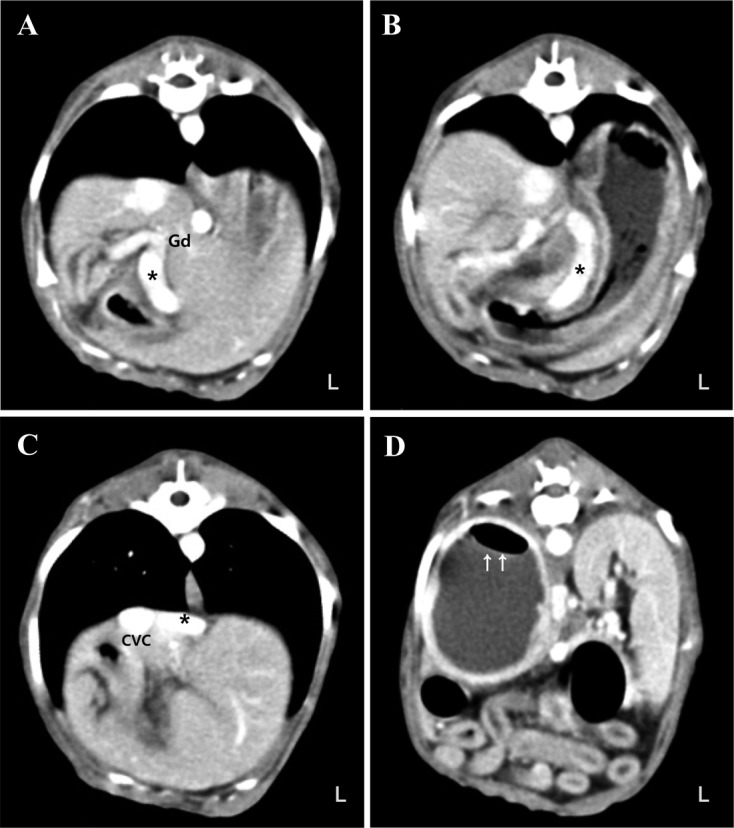

On radiographs, right-sided renomegaly and microhepatica were identified. A well-defined round shaped gas opacity was superimposed with enlarged right kidney (Fig. 1). On ultrasonography (Xario SSA-660A, Toshiba Medical Systems Corp., Otawara, Japan), the right renal pelvis was dilated containing echogenic fluid. Reverberation and bright speckles with dirty shadowing were found just below the medial interface of the diverticuli consistent with free gas (Fig. 1). An 18.1 mm-wide spindle-shaped and hyperechoic structure with distal shadowing was identified. It was consistent with cranial ureteral dilation. Urinary bladder was thickened irregularly. It was filled with echogenic sludge. Its liver was diffusely hyperechoic. The main portal vein was small in diameter. The extrahepatic portal flow was reduced. A dual-phase computed tomographic angiogram (CTA) was performed (Somatom Emotion, Siemens, Muenchen, Germany). Iodinated contrast medium (Omnipaque, GE healthcare, Cork, Ireland) was administered (814 mgI/kg) at 1 ml/sec into a cephalic vein by an automatic angiographic injector (CT 9000ADV, Liebel-Flarsheim, Cincinnati, OH, U.S.A.). Images were acquired from the start of arterial phase at 12 sec and portal phase at 33 sec after administrating the contrast medium in compliance of a previous study [26]. The shunting vessel arose from the gastroduodenal vein and extended ventrally leftward and cranially along the lesser curvature of the stomach. It passed cranial to the liver along the diaphragm and connected to the caudal vena cava from the left side via the phrenic vein (Fig. 2). Right kidney was filled with non-enhancing content with a small amount of gas (Fig. 2). Calculi were identified in the right ureter and the left renal pelvis. Based on these findings, emphysematous pyonephrosis with a congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunt (EHPSS) was the tentative diagnosis.

Fig. 1.

Ventrodorsal view (A) and right lateral view (B) of abdominal radiographs showing gas opacity (arrowhead) superimposed on enlarged right kidney. Small intestine in cranial abdomen is displaced ventrally to kidney with microhepatica (B). A reverberation artifact (C, arrows) and bright speckles with distal acoustic shadowing (D) existed internally interfacing the diverticuli.

Fig. 2.

Computed tomographic angiogram of the abdomen. The shunting vessel (asterisk) arised from the gastroduodenal vein (Gd) and extended ventrally (A), leftward and cranially along the lesser curvature of the stomach (B). It passed cranially to the liver along the diaphragm and connnected to the caudal vena cava (CVC) from the left side via the phrenic vein (C). A small amount of gas (arrows) existed in the right kidney (D).

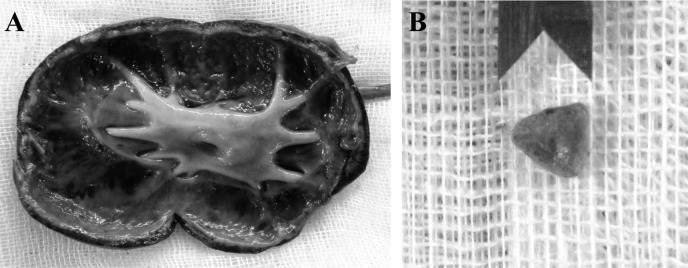

Ureteronephrectomy revealed that the renal pelvis was filled with a large amount of dark brown-colored pus. A yellowish green, 5.8 × 3.2 × 4.2 mm sized, and pyramidal-shaped calculus was presented in the right ureter (Fig. 3). Surgical correction of the EHPSS was performed around the shunt close to the caudal vena cava using surgically placed cellophane bands. Escherichia coli was isolated from the pus. Quantitative analysis of the urolith revealed 50% ammonium acid urate and 50% non-urolithic materials. After the surgical procedure, clinical signs were resolved. At follow-up of 5 months, no complication was observed.

Fig. 3.

Dorsal section of right kidney (A). Dilated renal pelvis with a destruction of the parenchyma is marked. A pyramidal-shaped calculus is in the right ureter (B).

Ammonium acid urate calculi are common in PSS patients. They can be associated with bacterial upper urinary tract infections [14, 17]. Patients with PSS often show hematologic changes, including nonregenerative anemia, leukocytosis, hypoalbuminemia, hypocholesterolemia, hypoglycemia and elevated serum liver enzyme [8, 24]. Although normal Maltese dogs have been reported to have elevated SBA, increases in postprandial SBA are sensitive markers to detect PSS in dogs [1,2,3, 8, 23]. In this case, ammonia tolerance test was excluded, because all clinical signs and hematologic changes indicated that the patient might have PSS. Septicemia was also suspected due to suppurative destruction of the right kidney consistent with hematologic abnormalities.

If the kidney is unilaterally enlarged on radiography, hydronephrosis, renal tumor and subcapsular hematoma or abscess could be considered [22]. Although ureteral calculi are often radiopaque, urate stones are usually radiolucent [22]. According to previous reports, almost all dogs with pyonephrosis have conspicuous obstruction in the renal collecting system [5, 13, 20]. In this case, the right kidney was dilated with pus due to urinary obstruction by urate stone and UTIs. In addition, the pyramidal shape of the stone suggested that urolith could have formed in the renal pelvis and dislodged into the ureter. Imaging for the portal and hepatic vasculature is essential for diagnosis of PSS in a dog. Dual-phase CTA is a minimally invasive imaging modality. It provides excellent anatomic details of the hepatic and portal vasculature [26]. In this case, dynamic scan was not performed, because we were concerned about the nephrotoxicity related to iodinated contrast media [15]. Based on available literatures, this case was similar to right gastric-phrenic type [9, 11, 16, 21].

In animals with PSS, urinary disorders can be associated with bacterial UTIs [12, 14]. Detection of bacteria on urine sediment examination can strongly suggest bacterial UTIs [19]. Rod-shaped bacteria and neutrophils were identified in this case. Based on available literatures, E. coli is the most common offending organism in the kidney of dogs [12]. Although emphysematous change of kidney is usually associated with E. coli in humans, it has been discussed in dogs only in a few cases [4, 10, 12, 13, 20, 25]. In this case, free gas was identified in the right kidney, and E.coli was isolated from the pus in the right renal collecting system.

Emphysematous pyonephrosis with EHPSS is very rare in veterinary medicine, although a similar case has reported that ammonium urate urolith has resulted in hydronephrosis in a PSS dog [7]. In this case, more severe progression with obstructive lesion and UTIs complicated with suppurative and emphysematous change was found compared to the previous report. In addition, we cultured the bacteria and identified the causative organism.

In most cases, clinicians may consider UTIs and/or ureteral obstruction, if emphysematous and purulent change of kidney is identified. However, it is possible that the causes of obstructive ureter stone, such as EHPSS, are overlooked due to the severity of clinical symptoms. Therefore, detailed investigation using US and CT should be considered for cases with obstructive ureter stones. This report is unique due to the severe progression of pyonephrosis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of emphysematous pyonephrosis associated with congenital PSS in a dog.

REFERENCES

- 1.Center S. A., Erb H. N., Joseph S. A.1995. Measurement of serum bile acids concentrations for diagnosis of hepatobiliary disease in cats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 207: 1048–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center S. A., ManWarren T., Slater M. R., Wilentz E.1991. Evaluation of twelve-hour preprandial and two-hour postprandial serum bile acids concentrations for diagnosis of hepatobiliary disease in dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 199: 217–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Center S. A.1993. Serum bile acids in companion animal medicine. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 23: 625–657. doi: 10.1016/S0195-5616(93)50310-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi J., Jang J., Choi H., Kim H., Yoon J.2010. Ultrasonographic features of pyonephrosis in dogs. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 51: 548–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2010.01702.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christiansen J. S., Hottinger H. A., Allen L., Phillips L., Aronson L. R.2000. Hepatic microvascular dysplasia in dogs: a retrospective study of 24 cases (1987–1995). J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 36: 385–389. doi: 10.5326/15473317-36-5-385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colemen B. G., Arger P. H., Mulhern C. B., Jr, Pollack H. M., Banner M. P.1981. Pyonephrosis: sonography in the diagnosis and management. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 137: 939–943. doi: 10.2214/ajr.137.5.939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.da Silva Curiel J. M., Pope E. R., O’brien D. P., Schmidt D. A.1990. Ammonium urate urolith resulting in hydronephrosis and hydroureter in a dog with a congenital portosystemic shunt. Can. Vet. J. 31: 116–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ettinger S. J., Feldman E. C.2009. Liver and pancreatic diseases. pp. 1649–1654. In: Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 7th ed. (Duncan, L., Rudolph, P. and Harms, L. eds.), Saunders, St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukushima K., Kanemoto H., Ohno K., Takahashi M., Fujiwara R., Nishimura R., Tsujimoto H.2014. Computed tomographic morphology and clinical features of extrahepatic portosystemic shunts in 172 dogs in Japan. Vet. J. 199: 376–381. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang J. J., Tseng C. C.2000. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: clinicoradiological classification, management, prognosis, and pathogenesis. Arch. Intern. Med. 160: 797–805. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraun M. B., Nelson L. L., Hauptman J. G., Nelson N. C.2014. Analysis of the relationship of extrahepatic portosystemic shunt morphology with clinical variables in dogs: 53 cases (2009–2012). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 245: 540–549. doi: 10.2460/javma.245.5.540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ling G. V., Norris C. R., Franti C. E., Eisele P. H., Johnson D. L., Ruby A. L., Jang S. S.2001. Interrelations of organism prevalence, specimen collection method, and host age, sex, and breed among 8,354 canine urinary tract infections (1969–1995). J. Vet. Intern. Med. 15: 341–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madewell B. R., Creed J. E., Hopkins J. B.1975. Hydronephrosis and pyelonephritis in a dog. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 167: 377–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marretta S. M., Pask A. J., Greene R. W., Liu S.1981. Urinary calculi associated with portosystemic shunts in six dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 178: 133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morcos S. K., Thomsen H. S.2001. Adverse reactions to iodinated contrast media. Eur. Radiol. 11: 1267–1275. doi: 10.1007/s003300000729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson N. C., Nelson L. L.2011. Anatomy of extrahepatic portosystemic shunts in dogs as determined by computed tomography angiography. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 52: 498–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2011.01827.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson R. W., Couto C. G.2009. Hepatobiliary and exocrine pancreatic disorders. pp. 535–537. In: Small Animal Internal Medicine, 4th ed. (Duncan, L., and Winkel, A. eds.), Mosby, St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramanyam B. R., Raghavendra B. N., Bosniak M. A., Lefleur R. S., Rosen R. J., Horii S. C.1983. Sonography of pyonephrosis: a prospective study. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 140: 991–993. doi: 10.2214/ajr.140.5.991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swenson C. L., Boisvert A. M., Kruger J. M., Gibbons-Burgener S. N.2004. Evaluation of modified Wright-staining of urine sediment as a method for accurate detection of bacteriuria in dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 224: 1282–1289. doi: 10.2460/javma.2004.224.1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szatmári V., Ösi Z., Manczur F.2001. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous drainage for treatment of pyonephrosis in two dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 218: 1796–1799, 1778–1779. doi: 10.2460/javma.2001.218.1796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szatmári V., van Sluijs F. J., Rothuizen J., Voorhout G.2004. Ultrasonographic assessment of hemodynamic changes in the portal vein during surgical attenuation of congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunts in dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 224: 395–402. doi: 10.2460/javma.2004.224.395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thrall D. E.2013. The abdominal cavity: canine and feline. pp. 711–730. In: Textbook of Veterinary Diagnostic Radiology, 6th ed. (Duncan, L. ed.), Saunders, St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tisdall P. L. C., Hunt G. B., Bellenger C. R., Malik R.1994. Congenital portosystemic shunts in Maltese and Australian cattle dogs. Aust. Vet. J. 71: 174–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1994.tb03382.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tobias K. M., Besser T. E.1997. Evaluation of leukocytosis, bacteremia, and portal vein partial oxygen tension in clinically normal dogs and dogs with portosystemic shunts. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 211: 715–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong Y., Suh B., Parsons R., Telivala B., Haas N., Chen D., Greenberg R.2009. Emphysematous pyelonephritis caused by Pasteurella multocida. Infect. Med. 26: 60. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zwingenberger A. L., Schwarz T.2004. Dual-phase CT angiography of the normal canine portal and hepatic vasculature. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 45: 117–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2004.04019.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]