Abstract

Objectives

This study examines the cross-sectional associations of cognitive and physical function with life satisfaction in middle-class, community-dwelling adults aged 60 and older.

Study Design

Participants were 632 women and 410 men who had cognitive function tests (CFT) and physical function tasks (PFT) assessed at a clinic visit between 1988 and 1992, and who responded in 1992 to a mailed survey that included life satisfaction measures. Cognitive impairment was defined as ≤24 on MMSE, ≥132 on Trails B, ≤12 on Category Fluency, ≤13 on Buschke long-term recall, and ≤7 on Heaton immediate recall. Physical impairment was defined as participants’ self-reported difficulty (yes/no) in performing 10 physical functions. Multiple linear regression examined associations between life satisfaction and impairment on ≥1 CFT or difficulty with ≥1 PFT.

Main Outcome Measures

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; range:0–26) and Life Satisfaction Index-Z (LSI-Z; range:5–35).

Results

Participants’ average age was 73.4 years (range=60–94). Categorically defined cognitive impairment was present in 40% of men and 47% of women. Additionally, 30% of men and 43% of women reported difficulty performing any PFT. Adjusting for age and impairment on ≥1 CFT, difficulty performing ≥1 PFT was associated with lower LSI-Z and SWLS scores in men (β=−1.73, −1.26, respectively, p<0.05) and women (β= −1.79, −1.93, respectively, p<0.01). However, impairment on ≥1 CFT was not associated with LSI-Z or SWLS score after adjusting for age and difficulty with ≥1 PFT.

Conclusions

Limited cognitive function was more common than limited physical function; however, limited physical function was more predictive of lower life satisfaction. Interventions to increase or maintain mobility among older adults may improve overall life satisfaction.

Keywords: cognitive function, life satisfaction, physical function, successful aging

NTRODUCTION

The proportion of the U.S. population aged 65 years and older is currently 13% and is expected to increase to 20% by 2050 [1]. With this shifting U.S. demographic, a greater proportion of life years will be spent at older ages, and there has been growing interest in quality of life and successful aging. Knowledge of what defines aging “successfully” has evolved over the years.

According to Rowe and Kahn, successful aging involves three components: low levels of disease and disability; high cognitive and physical function; and active engagement with life [2]. More recent contributions emphasize the concept of life satisfaction [3], which has been suggested to be more important for successful aging than the presence or absence of illness or disability [4].

Previous studies have suggested that cognitive and physical functions are associated with life satisfaction [5–10]. For example, St. John et al. [6] reported lower life satisfaction among individuals with cognitive impairment and physical impairment among a Canadian population-based sample of 1,620 adults aged 65–85 years. Berg et al. [7] found that cognitive and physical function were positively correlated with life satisfaction in a Swedish population-based sample of elderly men and women aged 80 and older, but stepwise regression analyses showed that these measures did not account for a significant amount of variance in life satisfaction scores. Jopp et al. [9] found subjective health and activities of daily living to be predictive for life satisfaction among this sample of community-dwelling New York City adults aged 95–107 years. While these studies demonstrate associations between life satisfaction and cognitive and physical function, all but one were internationally-based, and they were either limited to the oldest old, assessed life satisfaction with a single scale not validated among older populations, or found associations only in bivariate analysis.

The present cross-sectional study examines the associations of cognitive and physical function with life satisfaction in a cohort of middle-class, community-dwelling men and women aged 60 years and older in the United States.

METHODS

Participants

Between 1972–74, 6,629 individuals from Rancho Bernardo, a geographically defined Southern California community, were enrolled in a study of heart disease risk factors. These individuals were followed ever since with periodic research clinic visits and mailed surveys. Participants for the present study consist of men and women who attended a follow-up clinic visit in 1988–92 (n=1,727) when cognitive function and physical function were assessed, and who also completed a mailed survey assessing life satisfaction in 1992. Participants who were younger than age 60 years (n=189), had a history of stroke (n=124) or Parkinson’s disease (n=16), were missing all cognitive (n=2) or physical function variables (n=1), or did not return the mailed questionnaire (n=332) were excluded. Additionally, those missing responses to three or more items on the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), or five or more items on the Life Satisfaction Index-Z (LSI-Z) (n=21) were also excluded, leaving a final sample of 1,042 participants (410 men and 632 women) for analysis. This study was approved by the University of California, San Diego Human Research Protections Program; all participants gave informed consent prior to participation.

Procedures

During the 1988–92 clinic visit, a self-administered survey was used to collect demographic and behavioral information including age, education (some college or more vs. no college), exercise three or more times per week (no/yes), alcohol consumption three or more times per week (no/yes), smoking history (never/past/current, amount smoked per day, years smoked). Individuals were also queried about their medical history, including physician-diagnosed cancer, diabetes, heart attack, arthritis and osteoporosis.

During an interview, physical function was assessed by asking whether participants had difficulty performing a variety of physical movements, including bending down to pick up lightweight items from the floor; lifting a ten-pound object up from the floor; reaching for an object above their head; getting into and out of an automobile; walking 2 or 3 blocks outside on level ground; climbing up 10 steps without stopping; and walking down 10 steps. Participants were also asked about functional tasks, including putting socks or stockings on either foot; doing heavy housework, such as scrubbing floors, washing windows, and yard work; and shopping for groceries or clothes.

Trained nurses measured height and weight with participants wearing light clothing and no shoes; body mass index (BMI), calculated as weight in kilograms (kg)/height in meters (m)2, was used as an estimate of obesity. Information on medication use, including estrogen replacement in women, was obtained and validated with pill containers and prescriptions brought to the clinic for that purpose.

Cognitive function was assessed by trained interviewers during a battery of standardized tests. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was used to assess orientation, registration, attention, calculation, language and recall [11]. Sub-tests of the MMSE included Serial 7s, which was calculated by having participants count backwards from 100 by increments of seven, and spelling the word “world” backwards, which assessed attention. Category Fluency was used to evaluate verbal memory by asking participants to name as many animals as possible in one minute [12]. The Trail-Making Test, Part B from the Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery (Trails B) tested visuomotor tracking and attention by having participants scan a page for 300 seconds to identify numbers and letters in specified sequences [13]. The Buschke-Fuld Selective Reminding Test was used to examine short- and long-term storage and retrieval of spoken words [14]. The Heaton Visual Reproduction Test was used to assess memory for geometric forms and included components of immediate recall, delayed recall and copying [15]. Concentration was evaluated using items from the Blessed Information Memory Concentration Test [16]. For Trails B and the Buschke-Fuld short-term memory test, higher scores indicate worse performance; for all other tests, higher scores indicate better performance. Previously defined cut-offs as provided by the UCSD Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) were available to categorically defined poor performance for five tests; specifically, participants were classified as having poor cognitive performance if scored ≤24 on total MMSE, ≥132 on Trails B, ≤12 on the Category Fluency test, ≤13 on the Buschke long term recall, and ≤7 on Heaton immediate recall.

Life satisfaction was assessed by response to a mailed survey using the LSI-Z [17] and SWLS[18]. The LSI-Z consists of 13 statements for which participants responded either “agree,” “disagree,” or “don’t know.” A response of “agree” to eight of the statements and “disagree” to the remaining five indicate satisfaction. Participants received two points for each response indicating satisfaction, one point for a response of “don’t know”, and zero points for each response indicating dissatisfaction. Scores range from 0–26 with higher values indicative of greater life satisfaction. The SWLS consists of five statements for which participants indicate their level of agreement on a seven-point Likert scale with one being “strongly disagree” and seven being “strongly agree.” Scores range from 5–35 with higher values indicating greater life satisfaction. Cronbach’s alpha for both men and women was 0.81 for LSI-Z and 0.88 for SWLS.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables, including means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous measures, and percentages for categorical measures. Pack-years of smoking was calculated as (the number of cigarettes smoked per day/20) × (the number of years smoked). Comparisons between men and women were performed using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square analysis for categorical variables; because of the significant differences found, all further analyses were stratified by sex. Differences in mean LSI-Z and SWLS scores by categories of covariates were examined using t-tests and ANOVA; covariates significantly associated with life satisfaction at p<0.15 were included in multivariable models. Multiple linear regression modeling was used to examine the association of cognitive function and physical function with life satisfaction while adjusting for age, education, exercise, alcohol use and history of chronic disease. Separate models were run examining each of the 12 continuous cognitive function variables, the five dichotomized variables that classify individuals as cognitively impaired or not impaired, as well as the 12 individual physical movement and functional task variables. In addition, to determine if a relatively low level of impairment makes a difference in life satisfaction, and whether that difference varies by type of impairment, participants were categorized on whether they had impairment on one or more cognitive function test (CFT) and whether they had difficulty on one or more physical movement or functional task (PFT). Finally, to assess the relative contributions of physical and cognitive function to life satisfaction, regression modeling was used to examine the associations of ≥1 CFT with life satisfaction adjusted for the impairment on ≥1 PFT and the association of ≥1 PFT with life satisfaction adjusted for impairment on ≥1 CFT. Tolerance values were calculated to assess collinearity among independent variables. Data were analyzed using SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC); all analyses were two-tailed with p<0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

At the 1988–92 visit, the average age of participants was 73.4 ±7.6 years (range=60–94); 70% had completed some college or more (Table 1). Men had higher LSI-Z and SWLS scores than women, but these differences were not statistically significant. As shown in Table 1, sex differences were observed in many CFT scores whereby women had significantly lower scores than men on serial 7’s, category fluency, and Heaton immediate recall and delayed recall (p’s <0.01), but higher scores on MMSE (p <0.01), “world” backwards (p <0.05), and Buschke total and long-term recall (p’s<0.01). Additionally women had higher scores on Trails B indicating poorer performance and lower scores on Buschke short-term recall indicating better performance than men (p’s<0.01). For most physical movements and functional tasks, more women than men reported difficulties in performance (p’s<0.01). Compared to men, significantly more women had impairment on ≥1 CFT (40% vs. 47%; p<0.05) and reported difficulty on ≥1 PFT (30% vs. 43%; p<0.01). Comparisons of men and women on other characteristics are shown in Table 1. Further analyses to examine effect-measure modification by age and gender were conducted. It was found that for LSI-Z, age was an effect modifier (P<0.05) for Heaton immediate recall, lifting a 10-lb object from the floor, shopping, and impairment on ≥ 1 cognitive function test; and gender was an effect modifier for Mini-Mental total score and getting in/out of automobile. For SWLS, age was an effect modifier for getting in/out of automobile, housework, and shopping; and gender was an effect modifier (P<0.05) Heaton copying (date not shown).

TABLE 1.

Comparisons of men and women by selected characteristics; Rancho Bernardo, 1988 – 1992

| CHARACTERISTIC; mean (SD) |

WOMEN (n = 632) |

MEN (n = 410) |

pa | ||

| Age (years) | 73.6 | (7.5) | 73.2 | (7.7) | 0.469 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.8 | (3.9) | 26.1 | (3.2) | <0.001 |

| Pack-years of smoking | 13.9 | (21.9) | 22.4 | (25.3) | <0.001 |

| LIFE SATISFACTION; mean score (SD) | |||||

| LSI-Z | 19.4 | (4.8) | 19.7 | (4.9) | 0.365 |

| SWLS | 25.1 | (6.0) | 25.8 | (5.7) | 0.075 |

| CHARACTERISTIC; n (% yes) | pc | ||||

| Some college or more | 399 | (63.6) | 322 | (79.9) | <0.001 |

| Exercise ≥ 3 times/week | 445 | (70.4) | 332 | (81.0) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol use ≥ 3 times/week | 268 | (42.4) | 226 | (55.1) | <0.001 |

| History of chronic diseased | 470 | (74.4) | 282 | (68.8) | 0.049 |

| Current estrogen use | 234 | (37.0) | -- | -- | |

| COGNITIVE FUNCTION; n (% poor performancee) | |||||

| MMSE | 26 | (4.1) | 36 | (8.8) | 0.002 |

| Category fluency | 78 | (12.3) | 40 | (9.8) | 0.198 |

| Trails B | 256 | (40.5) | 112 | (27.3) | <0.001 |

| Heaton immediate recall | 209 | (33.1) | 102 | (24.9) | 0.005 |

| Buschke long term recall | 47 | (7.4) | 72 | (17.6) | <0.001 |

| Impairment on ≥ 1 cognitive function test | 297 | (47.0) | 162 | (39.5) | 0.018 |

| PHYSICAL MOVEMENTS; n (% difficulty) | |||||

| Bending to pick up items from floor | 87 | (13.8) | 48 | (11.7) | 0.320 |

| Lifting a 10-lb object from floor | 78 | (13.1) | 16 | (4.0) | <0.001 |

| Reaching an object above the head | 65 | (10.3) | 18 | (4.4) | <0.001 |

| Walking 2 – 3 blocks on level ground | 49 | (7.8) | 11 | (2.7) | <0.001 |

| Walking down 10 steps | 36 | (5.8) | 15 | (3.7) | 0.129 |

| Climbing up 10 steps | 56 | (9.0) | 15 | (3.7) | 0.001 |

| Getting in/out of automobile | 83 | (13.1) | 29 | (7.1) | 0.002 |

| FUNCTIONAL TASKS; n (% difficulty) | |||||

| Putting on socks/stockings | 89 | (14.1) | 45 | (11.0) | 0.138 |

| Doing heavy house work | 147 | (27.4) | 31 | (8.3) | <0.001 |

| Shopping | 16 | (2.5) | 2 | (0.5) | 0.014 |

| Difficulty on ≥ 1 physical movement or functional task | 271 | (42.9) | 121 | (29.5) | <0.001 |

P-values are based on t-tests and demonstrate significant differences between men and women by each characteristic;

Higher scores suggests poorer performance;

P-values are based on chi-square tests and demonstrate significant differences between men and women by each characteristic;

Includes cancer, diabetes, heart attack, arthritis and osteoporosis;

Poor performance: MMSE ≤ 24; Category fluency ≤ 12; Trails B ≥132; Buschke ≤ 13; Heaton ≤ 7

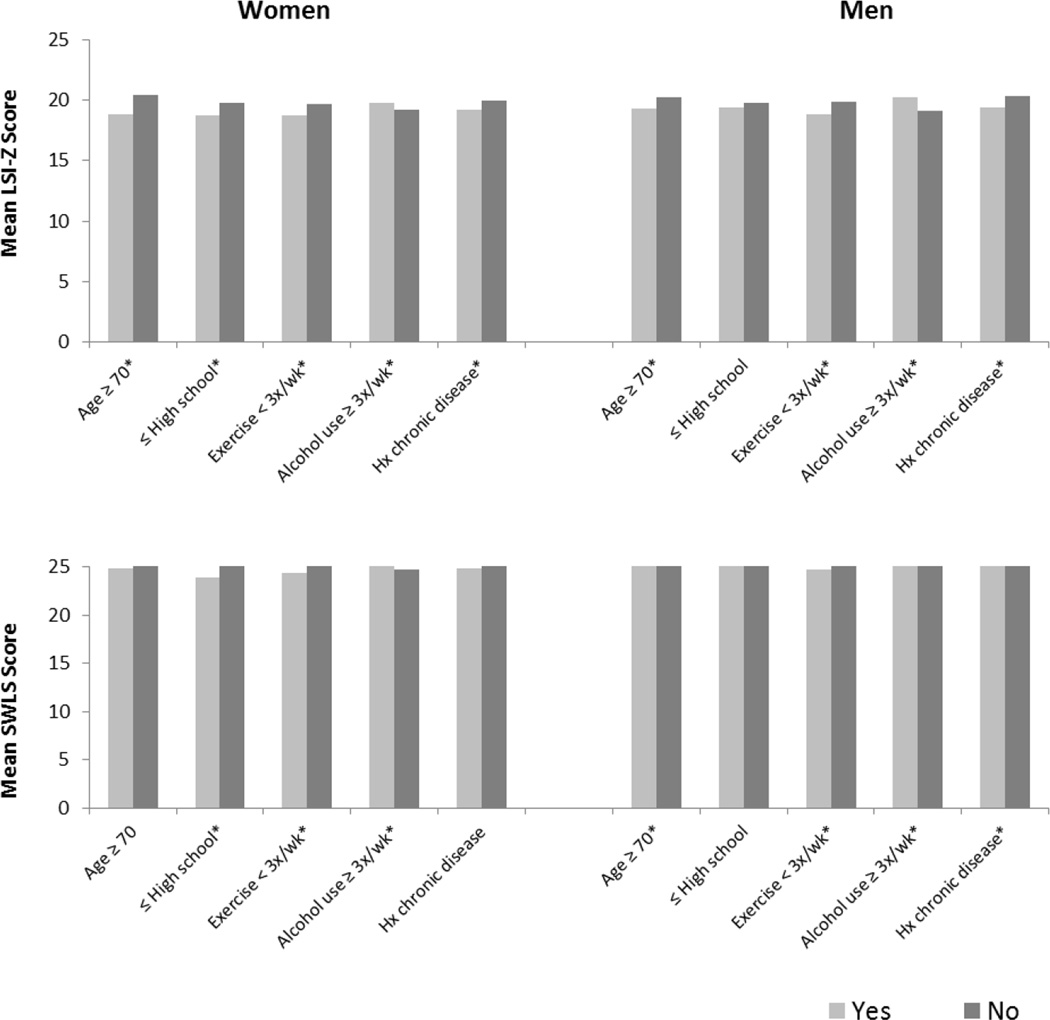

Figure 1 shows comparisons of mean life satisfaction scores by categorical covariates in men and women. As shown, life satisfaction scores (LSI-Z or SWLS) differed by age, education, exercise, alcohol use, and history of chronic disease (p<0.15); these values were therefore included in the multivariate analysis. Life satisfaction scores did not differ by BMI, pack-years of smoking, or current estrogen use among women (data not shown). Tolerance values were >0.10 for all independent variables.

FIGURE 1.

Comparisons of age and age-adjusted LSI-Z and SWLS scores by selected characteristics in women and men; Rancho Bernardo, 1988 – 1992

*p <0.15; p-values are based on t-tests or ANCOVA and demonstrate significance of differences between mean values of life satisfaction scores by age category or by each characteristic; History of chronic disease includes history of cancer, diabetes, heart attack, arthritis and osteoporosis

Associations of each cognitive function score with life satisfaction after adjustment for covariates are shown in Table 2. In women, better performance on MMSE, category fluency, Trails B, Heaton immediate and delayed recall, and Buschke total recall, long-term recall, and short-term recall were each associated with significantly higher life satisfaction scores (p’s<0.05). In men, higher scores on category fluency, Trails B, Heaton immediate recall, delayed recall and copying, and Buschke total and long-term recall were each associated with significantly higher life satisfaction scores (p’s<0.05). However, for both men and women, examination of the beta weights indicated that even statistically significant differences in life satisfaction scores were very small, amounting to less than a one point increase in life satisfaction per unit increase (or 20 unit increase for Trails B) in cognitive function. After adjustment for covariates, Serial 7’s, “World” backwards and Blessed were not significantly associated with either measure of life satisfaction (p’s>0.05).

TABLE 2.

Adjusteda associations of cognitive function scores with life satisfaction in men and women; Rancho Bernardo, 1988 – 1992

| Cognitive function test | Women | Men | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSI-Z | SWLS | LSI-Z | SWLS | |||||

| β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | |

| Mini-Mental: Total score | 0.25 | 0.040 | 0.03 | 0.838 | 0.03 | 0.742 | −0.04 | 0.747 |

| Mini-Mental: Serial 7’s | 0.11 | 0.402 | 0.01 | 0.939 | 0.01 | 0.986 | 0.12 | 0.620 |

| Mini-Mental: “World” backwards | 0.23 | 0.481 | 0.34 | 0.438 | 0.22 | 0.397 | 0.25 | 0.426 |

| Category fluency | 0.10 | 0.019 | 0.13 | 0.019 | 0.10 | 0.048 | 0.07 | 0.249 |

| Trails Bb (per 20 second) | −0.14 | 0.035 | −0.14 | 0.113 | −0.40 | <0.001 | −0.01 | 0.018 |

| Blessed items | 0.27 | 0.098 | 0.26 | 0.224 | −0.08 | 0.685 | −0.33 | 0.130 |

| Heaton Visual: Immediate recall | 0.23 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 0.049 | 0.19 | 0.011 | 0.19 | 0.036 |

| Heaton Visual: Delayed recall | 0.23 | <0.001 | 0.18 | 0.012 | 0.17 | 0.009 | 0.13 | 0.086 |

| Heaton Visual: Copying | 0.06 | 0.590 | −0.11 | 0.431 | 0.33 | 0.020 | 0.16 | 0.346 |

| Bushke: Total recall | 0.07 | 0.006 | 0.02 | 0.603 | 0.07 | 0.030 | 0.04 | 0.307 |

| Bushke: Long-term recall | 0.05 | 0.008 | 0.01 | 0.597 | 0.05 | 0.040 | 0.03 | 0.289 |

| Bushke: Short-term recallb | −0.10 | 0.042 | −0.03 | 0.624 | −0.07 | 0.207 | −0.05 | 0.447 |

| MMSE ≤ 24 | −1.67 | 0.079 | −0.24 | 0.851 | 0.53 | 0.553 | 0.19 | 0.855 |

| Category fluency ≤ 12 | 0.17 | 0.773 | 0.96 | 0.202 | −0.49 | 0.568 | −0.60 | 0.56 |

| Trails Bb ≥ 132 | −0.26 | 0.525 | −0.70 | 0.193 | −1.21 | 0.037 | −0.84 | 0.222 |

| Heaton immediate recall ≤ 7 | −1.04 | 0.014 | −0.82 | 0.140 | −1.02 | 0.092 | −0.82 | 0.252 |

| Buschke long term recall ≤13 | −0.67 | 0.355 | 1.06 | 0.265 | −0.62 | 0.375 | 0.09 | 0.909 |

| Impairment on ≥ 1 cognitive function test |

−0.36 | 0.379 | −0.47 | 0.383 | −0.96 | 0.084 | −0.95 | 0.148 |

Results of multiple linear regression analyses adjusted for age, education, exercise, alcohol use, and history of chronic disease (cancer, diabetes, heart attack, arthritis and osteoporosis);

Higher scores suggest poorer performance

Comparisons of life satisfaction by categorically defined poor performance on CFT are also shown in Table 2. After adjusting for covariates, men who had poor performance on Trails B (≥132) (p=0.04), and women who had poor performance on Heaton immediate recall (≤7) (p=0.01) had significantly lower LSI-Z scores. As above, although significant, differences in life satisfaction scores were very small. There were no other differences in life satisfaction by categorical performance on CFT or on impairment of one or more CFT.

Table 3 shows adjusted associations of difficulty in performing physical movements and functional tasks with life satisfaction. After controlling for covariates, women who reported difficulty lifting a 10 pound object from the floor had significantly lower LSI-Z scores (p<0.05), and those reporting difficulty reaching an object above their head, performing heavy housework, and shopping had significantly lower LSI-Z and SWLS scores (p’s<0.05) compared to those who did not report difficulty; differences ranged from 1.26 to 3.52 points on LSI-Z and from 2.00 to 5.42 points on SWLS. Men who reported difficulty bending to pick up items from the floor, walking down 10 steps, getting into or out of an automobile, and doing heavy house work had significantly lower LSI-Z scores (p’s<0.05) compared to those who did not report difficulty, with differences ranging from 1.72 to 3.11 points. In addition, among those who reported difficulty on ≥1 PFT, women had significantly lower LSI-Z and SWLS scores (p’s<0.01) and men had significantly lower LSI-Z scores (p<0.01) No other physical movements or functional tasks were significantly associated with life satisfaction.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted associations of difficulty performing physical movements and functional tasks with life satisfaction in men and women; Rancho Bernardo, 1988 – 1992

| Physical movement, difficulty with | Women | Men | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSI-Z | SWLS | LSI-Z | SWLS | |||||

| β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | |

| Bending to pick up items from floor | −0.48 | 0.386 | −0.79 | 0.269 | −1.72 | 0.022 | −0.83 | 0.453 |

| Lifting a 10-lb object from floor | −1.26 | 0.031 | −1.01 | 0.181 | −0.38 | 0.770 | −1.18 | 0.453 |

| Reaching an object above the head | −1.76 | 0.004 | −2.00 | 0.013 | −1.92 | 0.120 | −1.51 | 0.325 |

| Walking 2 – 3 blocks on level ground | −1.32 | 0.065 | −1.60 | 0.089 | −2.49 | 0.097 | 2.76 | 0.114 |

| Walking down 10 steps | −0.25 | 0.760 | −0.81 | 0.470 | −3.03 | 0.019 | −0.51 | 0.737 |

| Climbing up 10 steps | −1.05 | 0.125 | −1.55 | 0.094 | −1.20 | 0.352 | −0.15 | 0.920 |

| Getting in/out of automobile | −0.34 | 0.551 | −0.08 | 0.918 | −3.11 | <0.001 | −2.12 | 0.057 |

| Functional task, difficulty with | ||||||||

| Putting on socks/stockings | −0.26 | 0.635 | −0.41 | 0.569 | −0.42 | 0.586 | −0.41 | 0.658 |

| Doing heavy house work | −1.98 | <0.001 | −2.50 | <0.001 | −2.39 | 0.012 | −0.63 | 0.568 |

| Shopping | −3.52 | 0.003 | −5.42 | 0.001 | −− | −− | −− | −− |

| Difficulty on ≥ 1 physical movement or functional task |

−1.55 | <0.001 | −1.93 | <0.001 | −1.46 | 0.008 | −0.83 | 0.202 |

Results of multiple linear regression analyses adjusted for age, education, exercise, alcohol use, and history of chronic disease (cancer, diabetes, heart attack, arthritis and osteoporosis)

After controlling for all covariates and for cognitive impairment, women who had physical impairment on one or more physical or functional tasks had significantly lower LSI-Z and SWLS scores and men had significantly lower LSI-Z scores (p’s<0.05) (Table 4). However, after controlling for all covariates and physical impairment, cognitive impairment was no longer statistically associated with life satisfaction.

TABLE 4.

Adjusteda associations of cognitive function (CFT) and physical function (PFT) with life satisfaction in men and women; Rancho Bernardo Study, 1988 – 1992

| Women | Men | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSI-Z | SWLS | LSI-Z | SWLS | |||||

| Β | p | Β | p | Β | p | Β | p | |

| Impairment on ≥ 1 CFT | −0.36 | 0.379 | −0.47 | 0.383 | −0.96 | 0.084 | −0.95 | 0.148 |

| Difficulty on ≥ 1 PFT | −1.55 | <0.001 | −1.93 | <0.001 | −1.46 | 0.008 | −0.83 | 0.202 |

Results of multiple linear regression analyses adjusted for age, education, exercise, alcohol use, and history of chronic disease (cancer, diabetes, heart attack, arthritis and osteoporosis) and other variables shown.

Analyses to evaluate survival bias comparing individuals who did and did not return the mailed survey revealed participants who did not return the survey were significantly older, had lower CFT scores, and reported more difficulty performing PFT (p’s<0.05; data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Given the aging of the U.S. population, there is increasing interest in understanding factors associated with good life satisfaction. This analysis of community-dwelling men and women aged 60 years and older indicates that lower cognitive function and increased difficulty performing physical movements and functional tasks were both associated with decreased life satisfaction. Decrements in physical functioning had larger independent effects on life satisfaction than decrements in cognitive function.

Results of this study are consistent with those of a Canadian study by St. John et al. [6], which showed that among community-dwelling men and women aged 85 years and older, there were only slightly lower life satisfaction scores reported among participants with dementia and those with cognitive impairment no dementia (CIND), than among those with normal cognitive function based on MMSE scores. However, impairment of instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) was strongly predictive of overall life satisfaction among these Canadian community-dwelling older adults, along with education, income security, and depressive symptoms. Another study by Jopp et al. [9] among New York City elderly adults found personal activities of daily living and subjective health to be predictive of life satisfaction; however, cognitive function was not.

On the contrary, some recent international studies of life satisfaction did not find associations between cognitive or physical function and life satisfaction [19]. Most prior studies of life satisfaction were conducted in specific patient populations, such as spinal cord injury [20, 21], or cancer [22–24]. Others examining adults living outside of the U.S. [6, 7, 10, 19, 25–30] were not restricted to older age groups [31], or were published more than 30 years ago [32–35]. Most prior studies conducted among older populations did not assess the association of life satisfaction with cognitive function or physical function [36–38].

The finding that decrements in physical functioning have a stronger effect than cognitive function on life satisfaction is plausible. Individuals who have physical restrictions preventing them from completing everyday tasks or who require assistance to complete these tasks may suffer more than those who do not require assistance but may have mild cognitive impairment. Health-related quality of life has been studied extensively, with studies reporting that poor health and physical limitations are related to decreased well-being and quality of life [39–42].

Results of this study are in contrast with other studies which found life satisfaction and cognitive functions were associated with other factors that were not available for analysis in this data. For instance, Berg et al. reported that life satisfaction in Swedish adults was more influenced by factors such as quality of social network, self-rated overall health, and internal locus of control among women, and quality of social network, internal locus of control and being a widower among men [7]. Mhaoláin et al. in a sample of 466 community-dwelling men and women 65 years and older in Ireland found no association of MMSE or instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) with life satisfaction, but personality and mental health characteristics such as loneliness, neuroticism, extroversion, and exhaustion were associated with life satisfaction [25].

Several study limitations were considered. The cross-sectional nature of our study prevents the temporal association of cognitive and physical function with life satisfaction from being determined. In addition, generalizability may be limited because our study cohort consisted of relatively well-educated, Caucasian, middle-class adults who moved to southern California for the weather and who had good access to medical care and health insurance. The homogeneity of our cohort provided an opportunity to examine associations of physical function and cognitive function with life satisfaction in the absence of potential confounding from variables such as race, socioeconomic status, and lack of access to healthcare. Reporting or response biases are potential limitations here because life satisfaction measures were self-reported by a mail survey. Those who did not return the mail survey were older, had lower cognitive function scores, and reported more difficulty performing physical movements and functional tasks (data not shown), suggesting that the observed CFT-life satisfaction and PFT-life satisfaction associations are likely conservative.

This study also has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first U.S. study of community-dwelling men and women with information allowing the simultaneous examination of both cognitive and physical function with life satisfaction in both sexes. Additionally, multiple measures of cognitive function as well as physical function were used offering insight into specific factors that may influence overall life satisfaction and the contributions of cognitive and physical function to life satisfaction.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, physical function may play a larger role in life satisfaction than cognitive function, and this association appears to be stronger among woman than men. Community interventions to increase physical activity and programs to sustain or improve mobility among older adults may enhance overall life satisfaction with aging.

Highlights.

In a sample of middle-class, community-dwelling adults aged over 60 years, limited cognitive function was more common than limited physical function

Physical function may play a larger role in life satisfaction than cognitive function

Impairment of physical function was associated with life satisfaction

Impairment of cognitive function was not associated with life satisfaction

More women than men had impairment of cognitive and physical functions

Acknowledgments

Funding

The Rancho Bernardo Study was funded by the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, grant number DK31801, and the National Institute on Aging, grants number AG07181 and AG028507. The funding sources had no involvement in the study design; collection, analysis or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

AR led the design, analysis, and manuscript writing of the study.

DK-S oversaw the design, analysis, and manuscript writing of the current study.

EB-C is the principal investigator on the Rancho Bernardo Study and supervised the design, analysis and writing of the study.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the University of California, San Diego Human Research Protections Program; all participants gave informed consent prior to participation.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Census Bureau. Statistical Abstract of the United States. [August, 19, 2012];2012 Available from: http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s0009.pdf.

- 2.Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging. Gerontologist. 1997;37(4):433–440. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 2006;14(1):6–20. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192501.03069.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montross LP, et al. Correlates of self-rated successful aging among community-dwelling older adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 2006;14(1):43–51. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192489.43179.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones TG, et al. Cognitive and psychosocial predictors of subjective well-being in urban older adults. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2003;17(1):3–18. doi: 10.1076/clin.17.1.3.15626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.St John PD, Montgomery PR. Cognitive impairment and life satisfaction in older adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 2010;25(8):814–821. doi: 10.1002/gps.2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg AI, et al. What matters for life satisfaction in the oldest-old? Aging Ment. Health. 2006;10(3):257–264. doi: 10.1080/13607860500409435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melendez JC, et al. Psychological and physical dimensions explaining life satisfaction among the elderly: A structural model examination. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2009;48(3):291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jopp DS, et al. Physical, cognitive, social and mental health in near-centenarians and centenarians living in New York City: findings from the Fordham Centenarian Study. BMC geriatrics. 2016;16(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0167-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allerhand M, Gale CR, Deary IJ. The dynamic relationship between cognitive function and positive well-being in older people: a prospective study using the English Longitudinal Study of Aging. Psychology and aging. 2014;29(2):306–318. doi: 10.1037/a0036551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The mini-mental-state-examination - a comprehensive review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1992;40(9):922–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borkowsk Jg, Benton AL, Spreen O. Word fluency and brain damage. Neuropsychologia. 1967;5(2):135–140. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reitan RM. Validity of the trail making test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buschke H, Fuld PA. Evaluating storage, retention, and retrieval in disordered memory and learning. Neurology. 1974;24(11):1019–1025. doi: 10.1212/wnl.24.11.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell EW. Multiple scoring method for assessment of complex memory functions. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1975;43(6):800–809. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blessed G, Tomlinso.Be, Roth M. Association between quantiative measures of dementia and of senile change in cerebral grey matter of elderly subjects. Br J Psychiatry. 1968;114(512):797–811. doi: 10.1192/bjp.114.512.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood V, Wylie ML, Sheafor B. An analysis of a short self-report measure of life satisfaction: Correlation with rater judgements . J. Gerontol. 1969;24(4):465–469. doi: 10.1093/geronj/24.4.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diener E, et al. The satisfaction with life scale J. Pers. Assess. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campos AC, et al. Aging, Gender and Quality of Life (AGEQOL) study: factors associated with good quality of life in older Brazilian community-dwelling adults. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2014;12:166. doi: 10.1186/s12955-014-0166-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dijkers M. Correlates of life satisfaction among persons with spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1999;80(8):867–876. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Putzke JD, et al. Predictors of life satisfaction: A spinal cord injury cohort study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2002;83(4):555–561. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.31173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanda MG, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358(12):1250–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tate DG, Forchheimer M. Quality of life, life satisfaction, and spirituality - Comparing outcomes between rehabilitation and cancer patients. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2002;81(6):400–410. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morton RP. Life-satisfaction in patients with head and neck cancer. Clin. Otolaryngol. 1995;20(6):499–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1995.tb01588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mhaolain AMN, et al. Subjective well-being amongst community-dwelling elders: what determines satisfaction with life? Findings from the Dublin Healthy Aging Study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(2):316–323. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211001360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Enkvist A, Ekstrom H, Elmstahl S. What factors affect life satisfaction (LS) among the oldest-old? Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2012;54(1):140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han WJ, Shibusawa T. Trajectory of physical health, cognitive status, and psychological well-being among Chinese elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;60(1):168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerstorf D, et al. Secular changes in late-life cognition and well-being: Towards a long bright future with a short brisk ending? Psychology and aging. 2015;30(2):301–310. doi: 10.1037/pag0000016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gana K, et al. Does life satisfaction change in old age: results from an 8-year longitudinal study. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. 2013;68(4):540–552. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomás JM, et al. Predicting Life Satisfaction in the Oldest-Old: A Moderator Effects Study. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013;117(2):601–613. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strine TW, et al. The associations between life satisfaction and health-related quality of life, chronic illness, and health behaviors among US community-dwelling adults. J. Community Health. 2008;33(1):40–50. doi: 10.1007/s10900-007-9066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmore E, Kivett V. Change in life satisfaction – Longitudinal study of persons aged 46–70. J. Gerontol. 1977;32(3):311–316. doi: 10.1093/geronj/32.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palmore E, Luikart C. Health and social factors related to life satisfaction. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1972;13(1):68–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clemente F, Sauer WJ. Life satisfaction in United States. Soc. Forces. 1976;54(3):621–631. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edwards JN, Klemmack DL. Correlates of life satisfaction - Re-examination. J. Gerontol. 1973;28(4):497–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gueldner SH, et al. A comparison of life satisfaction and mood in nursing home residents and community-dwelling elders. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2001;15(5):232–240. doi: 10.1053/apnu.2001.27020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guerriero Austrom M, et al. Predictors of life satisfaction in retired physicians and spouses. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38(3):134–141. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0610-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis NC, Friedrich D. Knowledge of aging and life satisfaction among older adults. Int. J. Aging Human Dev. 2004;59(1):43–61. doi: 10.2190/U9WD-M79K-9HB8-G9JY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stewart AL, et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions - Results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA. 1989;262(7):907–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borglin G, et al. Self-reported health complaints and their prediction of overall and health-related quality of life among elderly people. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2005;42(2):147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Netuveli G, et al. Quality of life at older ages: evidence from the English longitudinal study of aging (wave 1) J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2006;60(4):357–363. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.040071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michalos AC, et al. Health and quality of life of older people, a replication after six years. Soc. Indic. Res. 2007;84(2):127–158. [Google Scholar]