Abstract

Objectives

To explore (1) the national trend in population-adjusted prescription rates for glaucoma and ocular hypertension (OHT) in England and (2) any geographical variation in glaucoma/OHT prescribing trends and its association with established risk factors for primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) at the population level.

Design

Observational ecological study.

Setting

Primary care in England 2008–2012.

Participants

All patients who received 1 or more of the 37 778 660 glaucoma/OHT prescription items between 2008 and 2012.

Primary and secondary outcome measure methods

Glaucoma/OHT prescription statistics for England and its constituent primary care trusts (PCTs) between 2008 and 2012 were divided by annual population estimates to give prescription rates per 100 000 population aged ≥40 years. To examine regional differences, prescription rates and the change in prescription rates between 2008 and 2012 for PCTs were separately entered into multivariable linear regression models with the population proportion aged ≥60 years; the proportion of males; the proportion of West African Diaspora (WAD) ethnicity; PCT funding per capita; Index of Multiple Deprivation 2010 score and its domains.

Results

Between 2008 and 2012, glaucoma/OHT prescriptions increased from 28 029 to 31 309 items per 100 000 population aged ≥40 years. Between PCTs, nearly a quarter of the variation in prescription rates in 2008 and 2012 could be attributed to age, WAD ethnicity and male gender. The change in prescription rates between 2008 and 2012 was only modestly correlated with age (p=0.003, β=0.234), and income deprivation (p=0.035, β=−0.168).

Conclusions

Increased population-adjusted glaucoma/OHT prescription rates in the study period were likely due to increased detection of POAG and OHT cases at risk of POAG. Between PCTs, regional variation in overall prescription rates was partly attributable to demographic risk factors for POAG, although the change in prescription rates was only modestly correlated with the same risk factors, suggesting potential variation in practice.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Population-based data for the whole of England over a period of 4 years.

Geographically linked prescription data covered almost 99% of all community glaucoma/ocular hypertension (OHT) prescriptions in public healthcare, allowing analysis of prescription data with relevant demographic and socioeconomic data on a population level.

Prescription data were not linked to individual patient records, which precluded calculation of actual patient numbers and the distinction of prescriptions dispensed for glaucoma from those dispensed for OHT.

Lack of data on glaucoma/OHT prescriptions in private medical care.

Data only allowed comparison of regional differences in prescription rates between primary care trusts but not variation with each trust, with each trust covering a wide geographical area and a large population.

Introduction

Glaucoma, a group of eye conditions with a characteristic type of optic nerve damage (cupping) and visual field defects, accounted for around 8% of registered blindness in England and Wales in 2008, making it the second leading cause of certified visual loss after age-related macular degeneration in these countries.1 Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), characterised by normal appearance of the iridocorneal angle, is the predominant form of glaucoma and accounts for around 74% of all glaucoma cases worldwide.2 POAG as the proportion of all glaucoma cases is likely to be higher in England, where widespread cataract surgery has been associated with a dramatic decline in primary angle closure glaucoma (PACG),3 the second major form of glaucoma.2 Cataract surgery is thought to reduce the incidence of PACG by removing the lens in older individuals and thus preventing ‘angle closure’ due to progressive age-related lens thickening causing occlusion of the iridocorneal angle.3 In absolute terms, POAG is estimated to affect at least 500 000 individuals in the UK.4

Two developments in England in the past decade might have led to an increase in the number of people who receive treatment for POAG. First, an ageing population profile due to rising life expectancy in the UK would result in a proportion of the population at risk of POAG.5 Denmark, a similarly developed country with an ageing population profile, was indeed found to have a rising prevalence of glaucoma in a recent study.6 Second, the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published a set of clinical guidelines in April 2009 concerning the diagnosis and management of POAG and ocular hypertension (OHT) to address uncertainty and variation in clinical practice.4 ‘OHT’ is a term commonly used to describe a condition in which the intraocular pressure (IOP) is elevated above 21 mm Hg without clinical evidence of glaucomatous optic nerve damage or visual field deficits,4 although a significant proportion of patients with OHT progress to develop POAG.7 The NICE guidelines4 recommended treatment of OHT in patients deemed at high risk of progression to POAG with IOP-lowering medications that are also used to treat POAG, as this approach has been shown to be cost-effective in reducing progression to POAG.7 8 Since the introduction of the NICE guidelines, local increases in glaucoma referrals9–11 and in glaucoma case detection have been reported.10 11 It has also been observed that the annual total number of glaucoma/OHT prescriptions in England had increased by 67% between 2000 and 2012.12 However, the changes in prescription rates relative to the underlying population, which would indicate any change in the population prevalence of treated glaucoma and OHT, have not been examined.

Any increase in rates of glaucoma/OHT prescriptions, however, might not be equally shared between the different regions in England. Malik et al13 has shown a nearly fivefold variation in outpatient ophthalmology expenditure in the fiscal year 2009/2010 between different regions in England, even after adjusting for age, sex and socioeconomic deprivation. The rates of trabeculectomy, the mainstay of surgical treatment for POAG, were also shown to have widespread geographical variation.14 It is not known whether any geographical variation in glaucoma/OHT treatment was associated with differences in populations at risk between these regions.

A few risk factors have been well established for POAG. There are likely genetic influences in the development of POAG, although twin studies show only a modest, albeit significant, inheritability index.15 16 Family history is important as having an affected first-degree relative increases the risk of developing POAG by 10 times.15 POAG is more common in people of the West African Diaspora (WAD) including African Caribbean or British West Indian people and African–Americans, compared with Europeans or Asians.17 18 The association of gender with the risk of POAG has been controversial,19 with conflicting results from different studies. Variation in study methods, small sample sizes and differences in the populations studied are likely to account for the inconsistent results seen. An extensive meta-analysis performed by Rudnicka et al19 included 61 267 POAG cases and reported POAG to be around 1.4 times more common in men than that in women, which is consistent with previous prescribing data from the UK.20 Most importantly, the incidence of POAG is known to rise with age. POAG is rare before the age of 4019 21 22 (but more common in people of the WAD) and has an OR of around 2 for every increase of a decade in age from the age of 40,19 with a mean age of onset of around 60 years of age.21 22 The population aged 40 years and over can therefore be considered the primary population at risk.

The objectives of this study were to explore (1) the national trend in population-adjusted prescription rates for glaucoma and OHT in England and (2) any geographical variation in glaucoma/OHT prescribing trends and its association with established risk factors for POAG at the population level.

Methods

Data collection

The National Health Service (NHS) in England, the largest single-payer publicly funded healthcare system in the world, was administered through 10 regional bodies called strategic health authorities (SHAs). SHAs were further subdivided into 151 local bodies called primary care trusts (PCTs) from October 2006 to March 2013. Each PCT responsible for a geographical area commissioned primary, community and secondary health services from providers, including hospitals. PCTs were collectively responsible for spending around 80% of the total NHS budget, accounting for a total expenditure of £164 billion in the financial years 2009/2010 and 2010/2011.23

General population data in England were derived from population census data. In England, the population census is conducted every 10 years, with the most recent census being conducted in 2011. Data from the 2011 census for the English population aged ≥40, ≥60 years, the number of males and the number of people of WAD ethnicity were tabulated for England overall and for each PCT. Mid-year population estimates from the Office of National Statistics were obtained for England and for each PCT to account for the variation in population each year. The number of people of WAD ethnicity was tabulated by the summation of the population counts under the categories ‘African’, ‘Caribbean’, ‘other black’, ‘mixed: white and black African’ and ‘mixed: white and black Caribbean’ in the 2011 census. The measure of each demographic group per 100 000 population was obtained by dividing the total number in the group by the total population and multiplying by 100 000.

The total number of annual prescriptions for glaucoma or OHT dispensed in the community, including those prescribed in hospital and dispensed in the community, was obtained for the whole of England for each of the financial years between 2008/2009 and 2012/2013 from the Health and Social Care Information Centre website.24 Separate annual data on prescriptions for the treatment of glaucoma or OHT, based on the reimbursement to dispensers for supplying products on prescription, were obtained for each PCT for the same period.24 The PCT data covered prescriptions dispensed in the community in the UK that were prescribed by general practitioners, nurses, pharmacists and other prescribers in the community in England. Prescriptions written in hospitals/clinics that were dispensed in the community as well as prescriptions dispensed in hospitals and private prescriptions were not included in the PCT data.

To explore whether the change in glaucoma/OHT prescription rates was associated with socioeconomic factors, the 2010 Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score25 was collected for each PCT. The IMD is a standardised index used in England as a measure of socioeconomic deprivation, and is constructed from seven different domains with the following weightage: (1) income—22.5%; (2) employment—22.5%; (3) health and disability—13.5%; (4) education, skills and training—13.5%; (5) barriers to housing and services—9.3%; (6) crime—9.3%; (7) living environment—9.3%. In general, the higher the IMD or domain score, the more deprived an area is.25 In particular, we investigated specific domain scores of interest including income, employment, health and disability, education, skills and training, as well as barriers to housing and services.

To investigate if overall healthcare funding could account for differences in glaucoma/OHT prescribing rates, total funding allocation and funding allocation per capita for each PCT were obtained for the financial year 2011/2012 from the Department of Health.

Calculation of prescription rates

The prescription rate was adjusted for the underlying population by dividing the number of prescriptions by the corresponding population estimate in the same year, and multiplying by 100 000 to give a prescription rate per 100 000 population. For the purposes of analysis in this study, the prescription rate per 100 000 of population aged ≥40 years was used, as this age group is considered the primary population at risk. The change in number of PCT prescriptions was calculated by subtracting the prescription rate in 2008/2009 from that in 2012/2013. The annual increment in prescription rate, which would indicate the number of new cases treated for glaucoma or OHT each year adjusted for the underlying population at risk, was calculated by subtracting the prescription rate in 1 year from the preceding year.

Statistical analysis

PCTs were anonymised by converting PCT names into serial numbers before data analysis. Glaucoma/OHT prescription rates and the change in glaucoma/OHT prescription rates of PCTs were separated into quintiles and plotted on choropleth maps of England PCT boundaries using the Quantum Geographical Information System (QGIS) V.2.4 for Macintosh OS. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics software V.21.0 for Macintosh OS. Any missing data were excluded from analysis by pairwise deletion. Pairwise correlations of continuous variables were carried out using Spearman's rank correlation. Correlation between multiple continuous variables and prescription rates were examined using multivariable linear regression. Multivariable linear regression was conducted in a forward conditional fashion, and variables fitted in the final model were examined for collinearity using their tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) values. Tolerance values of >0.1 and VIF values of <10 were taken to indicate the non-redundancy of variables and the consequent stability of the model(s). p Values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

There were no missing data. The total population in England increased from 49.1 million in the 2001 census to 53.0 million in the 2011 census (table 1). In the same period, the population aged ≥40 years rose from 22.9 to 26.0 million (an increase from 46.6% to 49.1% of total population), while the population aged ≥60 years rose 10.2–11.8 million (an increase from 20.1% to 22.3% of the total population). The population of WAD ethnicity rose from 1.4 to 2.4 million (an increase from 2.9% to 4.5% of total population).

Table 1.

England population statistics in 2001 and 2011

| 2001 census (% of total) | 2011 census (% of total) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age ≥40 years | 22 940 410 (46.7) | 25 995 642 (49.0) |

| Age ≥60 years | 10 199 830 (20.8) | 11 832 806 (22.3) |

| WAD ethnicity | 1 440 430 (2.93) | 2 423 780 (4.57) |

| Males | 23 922 144 (49.0) | 26 069 148 (49.2) |

| Total population | 49 138 831 (100) | 53 012 456 (100) |

WAD, West African Diaspora.

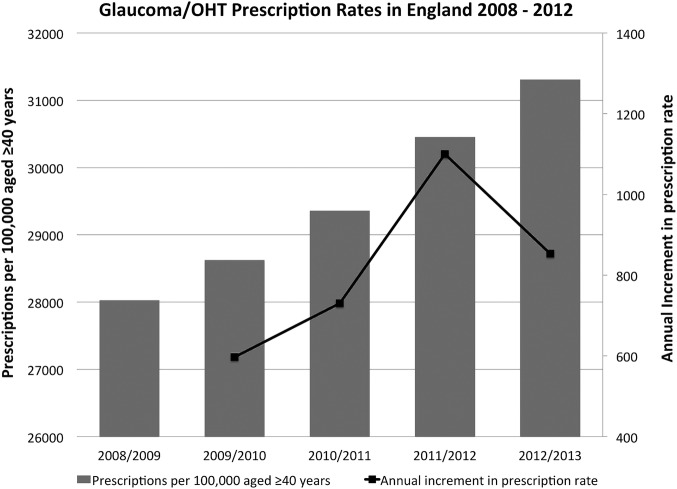

The total number of prescription items for glaucoma/OHT in England increased from 7.03 million items at a net cost of £97.6 million in 2008/2009 to 8.23 million items at a net cost of £105.2 million in 2012/2013. PCT prescriptions for glaucoma/OHT medications accounted for 98.7% of all community glaucoma/OHT prescriptions in 2008/2009 and for 99.0% in 2012/2013. When adjusted for population using mid-year estimates for the corresponding financial year, the number of prescription items increased from 28 029 to 31 309 items per 100 000 of the population aged ≥40 years during this period (figure 1). There was a year-on-year increase in the annual increment in prescription rates from 2009/2010 to 2011/2012 but the annual increment tailed off in 2012/2013 (figure 1). Between 2009/2010 and 2011/2012, the annual increment increased from 597 to 1100 per 100 000 of population aged ≥40 years, suggesting an increase in the annual incidence of new patients being treated for glaucoma or OHT in these years.

Figure 1.

Glaucoma/OHT prescriptions in England 2008–2012. Glaucoma/OHT prescriptions per 100 000 population aged 40 years and over are plotted as bar graphs and annual increment in glaucoma/OHT prescription rate is plotted as a line graph. OHT, ocular hypertension.

In the 2011 census, the median population in each PCT was 288 283, and the median population aged ≥40 years in each PCT was 129 634. Across PCTs, the median prescription rates per 100 000 population aged ≥40 years were 26 792 (IQR=7222) and 30 006 (IQR=8827) in 2008/2009 and 2012/2013, respectively. Between 2008/2009 and 2012/2013, there was an increase in the absolute number of prescription items for glaucoma/OHT for every PCT, with a median increase of 5900 items per PCT. When adjusted for population aged ≥40 years, there was an increase in the number of prescription items in all but six PCTs. The median increase per PCT was 2875 items per 100 000 population aged ≥40 years (IQR=2849).

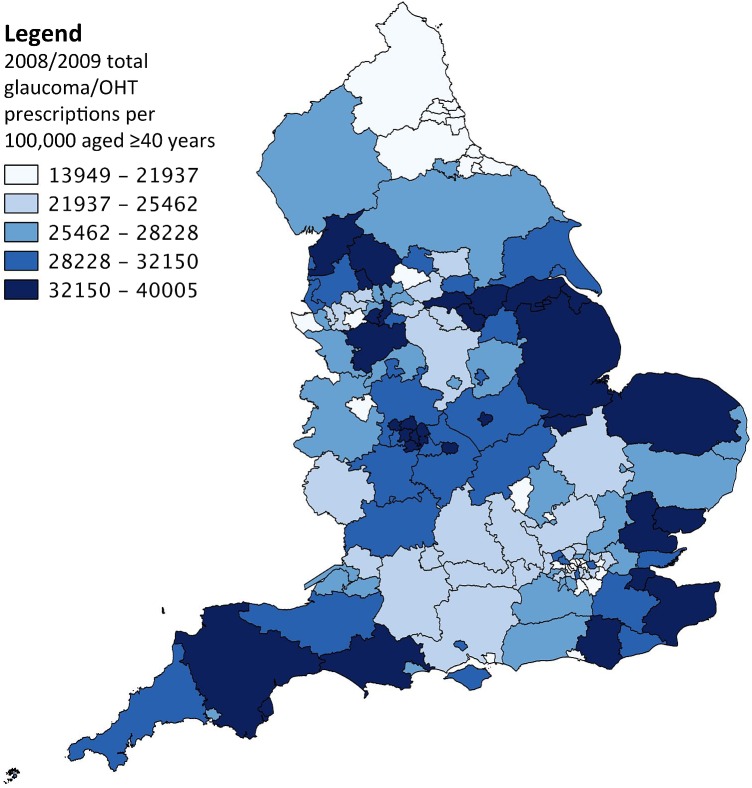

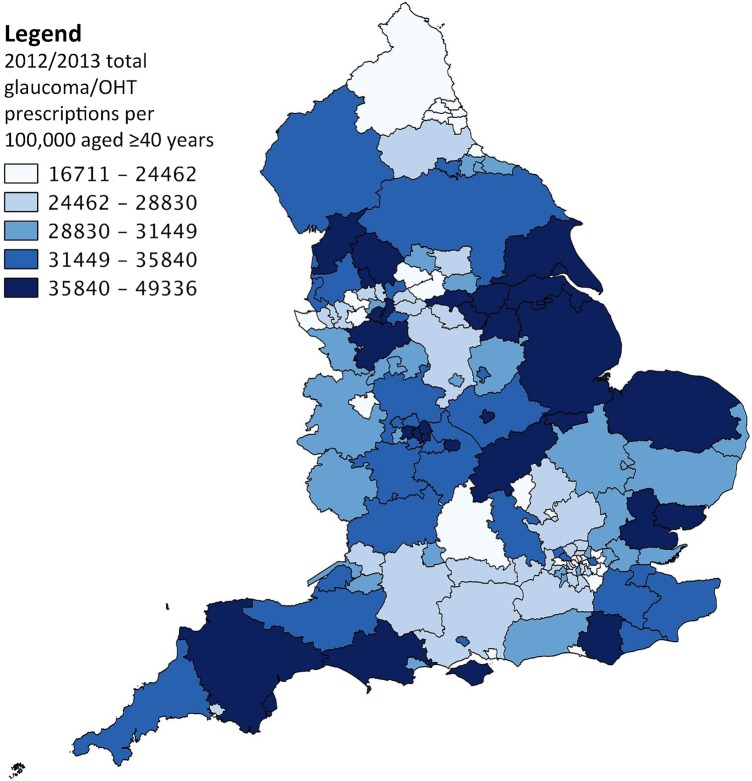

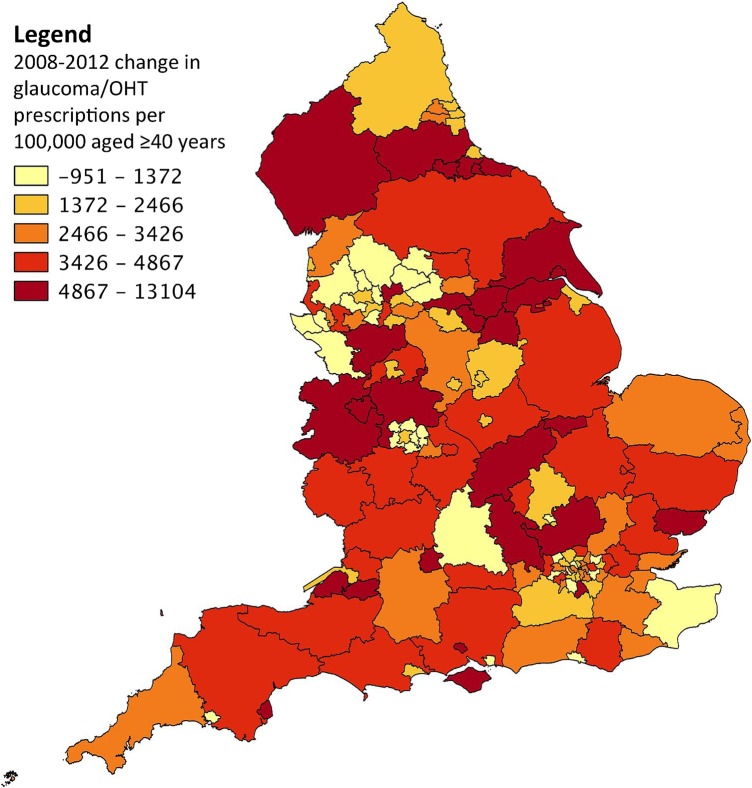

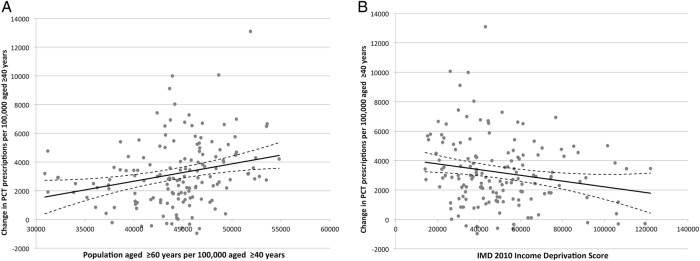

Regional differences in prescriptions per 100 000 population aged ≥40 years were apparent between PCTs in 2008/2009 (figure 2) and 2012/2013 (figure 3) with a nearly 3fold variation between the top and bottom quintiles. The change in prescription items per 100 000 of population aged ≥40 years showed even more pronounced regional differences with a nearly tenfold variation between the top and bottom quintiles (figure 4). The prescription rate per 100 000 population aged ≥40 years in 2008/2009 and 2012/2013 as well as the change in prescription rates between these 2 years for each PCT were separately correlated to the population aged ≥60 years per 100 000 aged ≥40 years, the number of males per 100 000 population, the number people of WAD ethnicity per 100 000 population, IMD 2010 score and its domains of interest and the total PCT fund allocation per capita using forward multivariable linear regression models. Prescriptions per 100 000 population aged ≥40 years in 2008/2009 (table 2) were positively correlated with the population aged ≥60 years per 100 000 aged ≥40 years (p<0.001, β=0.776), IMD 2010 income deprivation score (p=0.013, β=0.186), WAD ethnicity per 100 000 population (p=0.006, β=0.349) and males per 100 000 population (p=0.023, β=0.197). Prescriptions per 100 000 population aged ≥40 years in 2012/2013 (table 3) were positively correlated with the population aged ≥60 years per 100 000 aged ≥40 years (p<0.001, β=0.842), WAD ethnicity per 100 000 population (p=0.003, β=0.403) and males per 10 000 population (p=0.010, β=0.184). The change in prescriptions per 100 000 population aged ≥40 years between 2008/2009 and 2012/2013 (table 4) was positively correlated with the population aged ≥60 years per 100 000 aged ≥40 years (p=0.003, β=0.234), and negatively correlated with the IMD 2010 income deprivation score (p=0.035, β=−0.168). All tolerance values were above 0.1 and VIF values were <10, indicating that the models were stable. Univariable linear regression plots of the change in prescriptions per 100 000 population aged ≥40 years between 2008/2009 and 2012/2013 against the population aged ≥60 years per 100 000 aged ≥40 years (figure 5A) and the IMD 2010 income deprivation score (figure 5B) are shown. There was no correlation between the change in prescription items per 100 000 of population aged ≥40 years and prescriptions per 100 000 of population aged ≥40 years in 2008/2009 (Spearman r=0.073, p=0.373).

Figure 2.

Choropleth map of England PCTs showing glaucoma/OHT prescriptions per 100 000 population aged ≥40 years in 2008/2009, divided into quintiles. OHT, ocular hypertension; PCT, primary care trust.

Figure 3.

Choropleth map of England PCTs showing glaucoma/OHT prescriptions per 100 000 population aged ≥40 years in 2012/2013, divided into quintiles. OHT, ocular hypertension; PCT, primary care trust.

Figure 4.

Choropleth map of England PCTs showing change in glaucoma/OHT prescriptions per 100 000 population aged ≥40 years between 2008/2009 and 2012/2013, divided into quintiles. OHT, ocular hypertension; PCT, primary care trust.

Table 2.

Multivariable linear regression model for glaucoma/OHT prescription rate per 100 000 population aged ≥40 years in 2008/2009

| Variable | Β (95% CI) | β | p Value | R2 change | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of population aged ≥60 years per 100 000 aged ≥40 years | 0.931 (0.609 to 1.254) | 0.776 | <0.001 | 0.143 | 0.275 | 3.639 |

| Income deprivation | 0.047 (0.010 to 0.084) | 0.186 | 0.013 | 0.059 | 0.929 | 1.076 |

| WAD ethnicity per 100 000 | 0.297 (0.088 to 0.507) | 0.349 | 0.006 | 0.028 | 0.329 | 3.037 |

| Males per 100 000 | 1.691 (0.233 to 3.148) | 0.197 | 0.023 | 0.027 | 0.690 | 1.449 |

R2=0.257, adjusted R2=0.236.

OHT, ocular hypertension; VIF, variance inflation factor; WAD, West African Diaspora.

Table 3.

Multivariable linear regression model for glaucoma/OHT prescription rate per 100 000 population aged ≥40 years in 2012/2013

| Variable | Β (95% CI) | β | p Value | R2 change | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of population aged ≥60 years per 100 000 aged ≥40 years | 1.110 (0.760 to 1.459) | 0.842 | <0.001 | 0.190 | 0.281 | 3.557 |

| WAD ethnicity per 100 000 | 0.345 (0.120 to 0.569) | 0.403 | 0.003 | 0.033 | 0.344 | 2.905 |

| Males per 100 000 | 2.076 (0.505 to 3.648) | 0.184 | 0.010 | 0.034 | 0.712 | 1.405 |

R2=0.257, adjusted R2=0.242.

OHT, ocular hypertension; VIF, variance inflation factor; WAD, West African Diaspora.

Table 4.

Multivariable linear regression model for change in glaucoma/OHT prescription rate per 100 000 population aged ≥40 years from 2008/2009 to 2012/2013

| Variable | β (95% CI) | β | p Value | R2 change | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of population aged ≥60 years per 100 000 aged ≥40 years | 0.112 (0.038 to 0.187) | 0.234 | 0.003 | 0.064 | 0.989 | 1.012 |

| Income deprivation | − 0.017 (−0.033 to −0.001) | −0.168 | 0.035 | 0.028 | 0.989 | 1.012 |

R2=0.092, adjusted R2=0.079.

OHT, ocular hypertension; VIF, variance inflation factor.

Figure 5.

Univariable linear regression plots showing correlation between (A) change in glaucoma/OHT prescriptions per 100 000 aged ≥40 years with population aged ≥60 years per 100 000 aged ≥40 years; (B) change in glaucoma/OHT prescriptions per 100 000 aged ≥40 years with income deprivation. Ninety-five per cent CIs of the regression lines are indicated by broken lines. IMD, Index of Multiple Deprivation; OHT, ocular hypertension; PCT, primary care trust.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that the number of prescriptions for glaucoma/OHT medications had increased almost universally in England between 2008 and 2012 even after accounting for the increase in the primary population at risk of POAG (age ≥40 years). Moreover, the year-on-year increase in annual increment of prescription rates adjusted for the population at risk between 2008 and 2012 suggests an increase in the annual incidence of new patients being treated for glaucoma or OHT in these years. Assuming a constant population risk, this increase would suggest an increase in detection, rather than the true incidence, of predominantly POAG and OHT cases at risk of POAG. We also showed widespread geographical variation in population-adjusted glaucoma/OHT prescription rates which could be partially accounted for by risk factors for POAG, although the change in population-adjusted glaucoma/OHT prescription rates between 2008 and 2012 was only modestly correlated with the same risk factors.

The rise in the total number of glaucoma/OHT prescriptions in England over the past decade has been well documented.12 There were likely multiple factors underlying the change in glaucoma/OHT prescribing in such a large population, such as an ageing population, lower IOP targets and polypharmacy. An ageing population due to rising life expectancy, as evidenced by an increase in the population aged ≥40 years, was likely to drive a long-term increase in the prevalence of glaucoma and OHT. However, assuming a constant population at risk would mean that the population-adjusted incidence of new glaucoma/OHT cases should stay roughly constant over the span of a few years, unless there was a significant change in practice. Owing to our study period and the temporal trends in annual population-adjusted prescription rates as discussed above, we could not exclude the possible impact of the NICE 2009 guidelines on glaucoma/OHT treatment. The NICE guidelines were the first national guidelines in England on specifying the threshold, timing and mode of treatment in glaucoma and OHT. Following the publication of the NICE guidelines, previous studies have demonstrated an increase in the number of local glaucoma referrals.9–11 Rather than purely due to a direct impact of the NICE guidelines themselves, this increase might be partly due to the recommendation by the Association of Optometrists (AOP) in response to the NICE guidelines that all patients with a single measurement of IOP over 21 mm Hg should be referred to an ophthalmologist regardless of the type of tonometer used for measurement.26 The usefulness of this recommendation has been questioned,9 as it has led to an increased number of referrals for an isolated finding of an IOP >21 mm Hg since 2009 associated with a higher number of false positives.9 10 Subsequent studies have found a small increase in the absolute number of detected glaucoma cases at the expense of a fall in case detection rate.10 11 Our finding of an increase in the annual increment of prescription rates would suggest that there was a rise in the annual number of detected glaucoma and OHT cases across England in the study period, although our data could not examine the false-positive rate.

Overall, there was a threefold variation in population-adjusted glaucoma/OHT prescription rates across different PCTs. In multivariable linear regression models, up to a quarter of this variation could be accounted for by known risk factors for POAG in 2008/2009 and 2012/2013. These factors were namely age, WAD ethnicity and male gender. Unsurprisingly, age, as measured by proportion aged ≥60 years per 100 000 population aged ≥40 years, accounted for the most variation in these models—14.3% and 19.0% of the variation between PCTs in 2008/2009 and 2012/2013, respectively. The rise in contribution of age to the variation between PCTs during the study period was also reflected in the positive correlation of age with the change in prescription rates between 2008/2009 and 2012/2013. The positive correlation of male gender with glaucoma/OHT prescription rates is consistent with a previous extensive study on glaucoma prescribing in England20 but is contrary to the findings in a recent nationwide study of glaucoma prevalence and treatment in Denmark.6 The discrepancy in the association of gender in this instance is likely to be due to differences in the underlying population.

The possible reasons for the small positive correlation between income deprivation and population-adjusted glaucoma/OHT prescription rates between PCTs in 2008/2009 as well as the subsequent small negative correlation between income deprivation and the change in prescription rates between 2008/2009 and 2012/2013 remain unclear. Socioeconomic deprivation has been associated with late presentation to clinical services and visual loss in patients with glaucoma,27–30 but the impact of these findings on overall prescription rates is unknown.

Across England, there was a nearly 10-fold variation in the change in glaucoma/OHT prescriptions between PCTs in the top and bottom quintiles between 2008/2009 and 2012/2013. Compared with the variation in overall population-adjusted prescription rates, only a small fraction (around 8%) of the variation in this change in prescription rates could be explained by the variables examined in this study, indicating that demographic factors were not the predominant drivers behind the change in prescription rates across PCTs in our study period. This supports the notion that changes in practice were more likely responsible for the change in prescription rates.

Other factors which might have contributed further to variation in prescription rates as well as the change in prescription rates are more likely to relate to actual individual risk, such as family history and genetics, which are difficult to assess at a population level. Variation in practices of eye-care professionals between regions were also likely to have contributed to regional variations in prescriptions.

A major limitation of this study was that data on prescription items were not linked to individual patient records, which precluded the possibility of calculating the actual number of treated patients with glaucoma/OHT. As such, we were unable to exclude one-time prescriptions of IOP-lowering medications that could follow certain ocular surgeries (eg, cataract surgery, retina detachment surgery), although the contribution of such prescriptions to the total number of prescriptions was likely to be small. We also could not distinguish prescription items dispensed for glaucoma from those dispensed for OHT since the same medications are prescribed for both conditions. Another limitation was the lack of data on glaucoma/OHT prescriptions in private medical care. Having private prescription data would allow the elucidation of the actual burden of medical treatment for glaucoma/OHT in England. Finally, our study method was designed to examine regional differences in prescription rates between PCTs, but not variation within each PCT, which had a median population of over 200 000 in the 2011 census.

In conclusion, our study showed that population-adjusted glaucoma/OHT prescription rates in England were increasing. We also showed that although geographical variation in overall prescription rates was partially correlated with known demographic risk factors for POAG, the change in prescription rates in the study period was only modestly correlated with the same demographic risk factors. With an ageing population profile, the increasing healthcare burden of glaucoma is a formidable one. The total cost of medical treatment currently stands at £105.2 million in the financial year 2012/2013—an increase of £7.6 million since 2008/2009. The total cost of medical treatment would have been higher except for a decrease in the unit cost of the most commonly prescribed glaucoma medication, latanoprost, due to the expiry of its patent in January 2012.12 The actual costs of managing glaucoma in the National Health System, however, are likely to be much higher with the increased number of referrals, monitoring for an increased number of patients, and surgery for selected patients,31 32 which have not been calculated in this study. It is likely that variations in practice exist, which may impede the efficient allocation of resources for glaucoma treatment. Further investigation into such variation in practice is warranted, such that practice can be standardised to deliver uniform and equitable healthcare for all patients with glaucoma.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Office of National Statistics (ONS) for providing population data, the Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) for providing NHS administrative data and the Department of Health (DH) for providing statistics on funding and workforce.

Footnotes

Contributors: JSH performed data collection and statistical analysis. JSH, RW and PTK contributed to the drafting, editing and proof-reading of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. RW and PTK were supported in part by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Original prescription data available from http://www.hscic.gov.uk/prescribing.

References

- 1.Bunce C, Xing W, Wormald R. Causes of blind and partial sight certifications in England and Wales: April 2007–March 2008. Eye (Lond) 2010;24:1692–9. 10.1038/eye.2010.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90:262–7. 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keenan TDL, Salmon JF, Yeates D et al. Trends in rates of primary angle closure glaucoma and cataract surgery in England from 1968 to 2004. J Glaucoma 2009;18:201–5. 10.1097/IJG.0b013e318181540a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute of Clinical Excellence. Glaucoma—diagnosis and management of chronic open angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension. NICE Clinical Guideline 85, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuck MW, Crick RP. The projected increase in glaucoma due to an ageing population. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2003;23:175–9. 10.1046/j.1475-1313.2003.00104.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolko M, Horwitz A, Thygesen J et al. The prevalence and incidence of glaucoma in Denmark in a fifteen year period: a nationwide study. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0132048 10.1371/journal.pone.0132048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ et al. The ocular hypertension treatment study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:701–13; discussion 829–30 10.1001/archopht.120.6.701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kymes SM, Kass MA, Anderson DR et al. Management of ocular hypertension: a cost-effectiveness approach from the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;141:997–1008. 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah S, Murdoch IE. NICE—impact on glaucoma case detection. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2011;31:339–42. 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2011.00843.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ratnarajan G, Newsom W, French K et al. The effect of changes in referral behaviour following NICE guideline publication on agreement of examination findings between professionals in an established glaucoma referral refinement pathway: the Health Innovation & Education Cluster (HIEC) Glaucoma Pathways project. Br J Ophthalmol 2013;97:210–14. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Silva SR, Riaz Y, Purbrick RMJ et al. There is a trend for the diagnosis of glaucoma to be made at an earlier stage in 2010 compared to 2008 in Oxford, United Kingdom. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2013;33:179–82. 10.1111/opo.12030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connor AJ, Fraser SG. Glaucoma prescribing trends in England 2000 to 2012. Eye (Lond) 2014;28:863–9. . 10.1038/eye.2014.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malik ANJ, Cassels-Brown A, Wormald R et al. Better value eye care for the 21st century: the population approach. Br J Ophthalmol 2013;97:553–7. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keenan TDL, Salmon JF, Yeates D et al. Trends in rates of trabeculectomy in England. Eye (Lond) 2009; 23:1141–9. 10.1038/eye.2008.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolfs RC, Klaver CC, Ramrattan RS et al. Genetic risk of primary open-angle glaucoma. Population-based familial aggregation study. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116:1640–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teikari JM. Genetic factors in open-angle (simple and capsular) glaucoma. A population-based twin study. Acta Ophthalmol 1987;65:715–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tielsch JM, Sommer A, Katz J et al. Racial variations in the prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma. The Baltimore Eye Survey. JAMA 1991;266:369–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Racette L, Wilson MR, Zangwill LM et al. Primary open-angle glaucoma in blacks: a review. Surv Ophthalmol 2003;48:295–313. 10.1016/S0039-6257(03)00028-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rudnicka AR, Mt-Isa S, Owen CG et al. Variations in primary open-angle glaucoma prevalence by age, gender, and race: a Bayesian meta-analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006;47:4254–61. 10.1167/iovs.06-0299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owen CG, Carey IM, De Wilde S et al. The epidemiology of medical treatment for glaucoma and ocular hypertension in the United Kingdom: 1994 to 2003. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90:861–8. 10.1136/bjo.2005.088666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leske MC, Connell AM, Wu SY et al. Incidence of open-angle glaucoma: the Barbados Eye Studies. The Barbados Eye Studies Group. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mukesh BN, McCarty CA, Rait JL et al. Five-year incidence of open-angle glaucoma: the visual impairment project. Ophthalmology 2002;109:1047–51. 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01040-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson G. Primary care trusts: Funding and expenditure. Standard Note: SN/SG/5719, House of Commons Library. 2010;http://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN05719/SN05719.pdf (accessed 1 July 2015).

- 24.Prescribing - Health & Social Care Information Centre. Hscic.gov.uk. 2015. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/prescribing (accessed 1 July 2015).

- 25.McLennan D, Barnes H, Noble M et al. The English indices of deprivation 2010. London: Department for Communities and Local Government 2011. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/6320/1870718.pdf (accessed 1 July 2015).

- 26.Edgar D, Romanay T, Lawrenson J et al. Referral behaviour among optometrists: Increase in the number of referrals from optometrists following the publication of the April 2009 NICE guidelines for the diagnosis and management of COAG and OHT in England and Wales and its implications. Optom Pract 2010;11:33–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fraser S, Bunce C, Wormald R et al. Deprivation and late presentation of glaucoma: case-control study. BMJ 2001;322:639–43. 10.1136/bmj.322.7287.639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Day F, Buchan JC, Cassells-Brown A et al. A glaucoma equity profile: correlating disease distribution with service provision and uptake in a population in Northern England, UK. Eye (Lond) 2010;24:1478–85. 10.1038/eye.2010.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng WS, Agarwal PK, Sidiki S et al. The effect of socio-economic deprivation on severity of glaucoma at presentation. Br J Ophthalmol 2010;94:85–7. 10.1136/bjo.2008.153312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buys YM, Jin YP, Canadian Glaucoma Risk Factor Study Group. Socioeconomic status as a risk factor for late presentation of glaucoma in Canada. Can J Ophthalmol 2013;48:83–7. 10.1016/j.jcjo.2012.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung SD, Ho JD, Lin HC et al. Incremental healthcare service utilization for open-angle glaucoma: a population-based study. J Glaucoma 2015;24:e116–20. 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahman MQ, Beard SM, Discombe R et al. Direct healthcare costs of glaucoma treatment. Br J Ophthalmol 2013;97:720–4. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]