Abstract

Introduction

Many resources are required to provide postoperative care to patients who receive a cochlear implant. The implant service commits to lifetime follow-up. The patient commits to regular adjustment and rehabilitation appointments in the first year and annual follow-up appointments thereafter. Offering remote follow-up may result in more stable hearing, reduced patient travel expense, time and disruption, more empowered patients, greater equality in service delivery and more freedom to optimise the allocation of clinic resources.

Methods and analysis

This will be a two-arm feasibility randomised controlled trial (RCT) involving 60 adults using cochlear implants with at least 6 months device experience in a 6-month clinical trial of remote care. This project will design, implement and evaluate a person-centred long-term follow-up pathway for people using cochlear implants offering a triple approach of remote and self-monitoring, self-adjustment of device and a personalised online support tool for home speech recognition testing, information, self-rehabilitation, advice, equipment training and troubleshooting. The main outcome measure is patient activation. Secondary outcomes are stability and quality of hearing, stability of quality of life, clinic resources, patient and clinician experience, and any adverse events associated with remote care. We will examine the acceptability of remote care to service users and clinicians, the willingness of participants to be randomised, and attrition rates. We will estimate numbers required to plan a fully powered RCT.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was received from North West—Greater Manchester South Research Ethics Committee (15/NW/0860) and the University of Southampton Research Governance Office (ERGO 15329).

Results

Results will be disseminated in the clinical and scientific communities and also to the patient population via peer-reviewed research publications both online and in print, conference and meeting presentations, posters, newsletter articles, website reports and social media.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN14644286; Pre-results.

Keywords: OTOLARYNGOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This will be the first randomised controlled trial (RCT) of a triple approach to remote care for people using cochlear implants.

No formal power calculations were performed as this is the first study of its kind and acts as a feasibility RCT.

The generic Patient Activation Measure (PAM) may not be sensitive enough to show change in people with cochlear implants: a condition-specific empowerment measure may be required.

People using cochlear implants who volunteer to take part may not be representative of the population of people with implants.

Introduction

Cochlear implants are the most successful of all neural prostheses;1 they can provide hearing to people with severe to profound deafness. Approximately 1200 people receive a cochlear implant in the UK each year.2 The total number of people with implants is ∼14 000 in the UK and 600 000 worldwide.3 Numbers are likely to increase rapidly: only ∼5% of eligible people in the UK have received an implant,3 and the number of people of retirement age is projected to increase by 28% by 20354 meaning a further increase in the number of hearing-impaired people. Cochlear implant care in the UK is provided at 1 of 19 tertiary centres involving assessment, surgery, and a resource-intensive acute phase of device adjustment and rehabilitation. These centres may be several hours away from the patient's home necessitating travel expense, time off work and family disruption. Currently UK implant centres review patients on a clinic-led schedule; this means that review appointments can occur that provide little benefit to the patient. Conversely when some patients attend a routine appointment, there is hearing deterioration which the patient had not noticed. This is often remedied by replacing equipment that the patient could have done at home. Making this care pathway patient-centred instead may provide a more efficient and effective service and allow more timely identification of issues.

When a patient attends a long-term follow-up appointment, the following tasks may be performed: speech recognition testing, device adjustment, rehabilitation, equipment check and troubleshooting, and provision of replacement or upgraded equipment. We propose that at least some of these tasks could be performed by the patient themselves at home, and that people using cochlear implants should only attend the clinic when there is clinical need (no more routine appointments). Potential benefits for the patient are:

More stable hearing (problems identified and resolved quicker);

Better hearing (ability to fine tune when away from clinic);

Convenience of not travelling to routine appointments;

Reduction of travel cost and time, time off work and disruption to family life;

Increased confidence to manage own hearing;

Greater equality in service delivery (same level of service regardless of distance from clinic).

It may also mean that the clinic has greater resources (time, money, space) to see complex cases and the expanding population of new patients, although health economics analysis will not occur in this trial. People using cochlear implants and their families would generally like to take a more active role in their care and welcome the use of technology to assist self-care.5 6 The National Health Service (NHS) has a strong commitment to supporting self-care for people with long-term conditions7 with ‘the vision of a citizen-centred, digitally enabled, health and social care system’.8 Evidence shows a significant improvement in outcomes when patients use self-management tools9 and those who are activated and involved in their care tend to have better health outcomes.10 11

The standard clinical care pathway

Speech recognition testing

The main speech recognition measure used in UK clinics is Bamford-Kowal-Bench (BKB) sentences12 in quiet and noise; these are usually performed in a sound-treated room in the clinic by experienced clinicians, although there are some reports of testing remotely using an assistant at a remote location and video conferencing facilities.13 14 Speech perception in noise testing using digits has been developed;15 digits are highly familiar stimuli and are usually known by people with even basic language skills. Digit testing requires a closed set response and thus is suitable for self-testing over the telephone or internet16 17 and has a minimal learning effect.18 The test correlates well with speech recognition in noise with sentences in people using cochlear implants.19–22 A digit test in English is freely available online at the Action on Hearing Loss website23 and also as an application for mobile devices (Action on Hearing Loss Hearing Check).

Device adjustment

In order to provide benefit to a hearing-impaired person, the levels of electrical stimulation need to be individually adjusted for soft and loud sounds on up to 22 electrode contacts in the cochlea. The levels can change as the person using a cochlear implant becomes more used to listening, more experienced at doing the task and as physiological changes occur. Most cochlear implant centres offer frequent appointments in the first few months following implantation and annual adjustment appointments thereafter.24 Device adjustment usually occurs in the clinic in a sound-treated room, led by an experienced clinician. Several centres are now offering remote device programming.13 25–32 However, these reports continue to use a clinician-centred model involving the patient attending a centre closer to their home where an assistant is present, and the cochlear implant centre clinician leading the session using video conferencing and remote desktop connection.

People using cochlear implants have commented that they would like to be able to adjust their device parameters in their own home or work environment, rather than just in the sound-treated clinic room.5 The company Cochlear have introduced a self-fitting paradigm (Remote Assistant Fitting) using the speech processor remote control that patients already have. This allows adjustment of programming to be done by the patient at anytime and anywhere with equivalent hearing outcomes to audiologist-led sessions.33

Rehabilitation

Many clinical resources are devoted to rehabilitation after people receive a cochlear implant; the new sound can be difficult to get used to. Rehabilitation appointments are frequent in the first year and may be offered annually thereafter.34 Computer-based auditory training completed by the patient at home can significantly improve their speech recognition.35

Equipment troubleshooting/repairs/spares provision/upgrades

Cochlear implant speech processors are complex; some parts need regular replacement in order to keep the device in optimum condition.36 No reminder is given on the device. Many NHS cochlear implant centres offer an upgraded speech processor approximately every 5 years, requiring a clinic visit.34

The intervention

This paper describes the protocol for a feasibility project to design, introduce and evaluate a patient-centred remote care approach for adults using cochlear implants long term. This is necessary preparatory work for a fully powered randomised controlled trial (RCT) that will be extended across the UK. It is a prospective RCT whereby 60 patients will be randomised to either a control group (usual clinical care) or a remote care group where they are given access to new remote care tools. The patients in the remote care group will monitor their hearing at home, and some can fine tune their hearing to suit their own real-world environment. Their other needs will be met through a personalised online support tool. Assessment of front-line staff perceptions of remote care will also be formally evaluated using repeated interviews with 10 staff members at the start, midpoint and end of the project. Empowering the patient to self-care at home could enable better and more stable hearing and a more convenient and accessible service.

Methods and analysis

Trial design

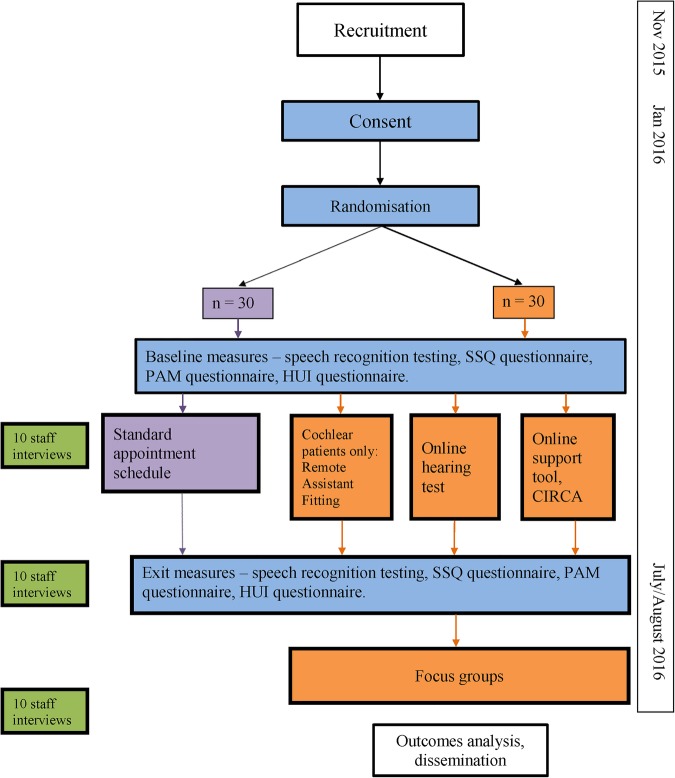

This will be a two-arm feasibility RCT involving 60 adults with cochlear implants with at least 6 months device experience in a 6-month clinical trial of remote care (see figure 1 flow chart). This feasibility trial will inform a later fully powered RCT and will be used to estimate characteristics of the outcome measures, follow-up rates, adherence, willingness of participants to be randomised, and the number of eligible and willing participants. The later substantive RCT will aim to answer the question ‘Is remote care an acceptable and effective method of caring for adults using cochlear implants?’ using more participants and a longer time scale.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of project. Items in blue apply to all enrolled cochlear implant users, purple: control group only, orange: remote care group only, green: staff. CIRCA, Cochlear Implant Remote Care; HUI, Health Utilities Index; PAM, Patient Activation Measure; SSQ, Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing.

Setting and participants

The trial will be conducted at the University of Southampton Auditory Implant Service (USAIS): a tertiary treatment centre mostly funded by NHS referrals. The study sponsor is the University of Southampton. The funder (The Health Foundation) and sponsor have not contributed towards the study protocol. Some anonymised data will be analysed at the University of Nottingham. Participants will not necessarily be USAIS patients.

Proposed sample size

No formal power calculations were performed as this is a feasibility trial to plan a later RCT. The literature suggests sample sizes between 30 and 50 for a feasibility trial.36 37 Sixty participants was selected (30 in each group) in order to gather a range of different service users’ experiences of the remote care tools and to estimate the effect size on the primary outcome measure.

Recruitment

Potential participants will be sent a covering letter and the Participant Information Sheet several weeks before consenting. The clinical trial will begin in January 2016. There has been much interest in the project among people using cochlear implants in the UK, so adequate enrolment to reach target size is not of concern.

The principal investigator (PI; HC) will access the USAIS clinical database and contact patients who fulfil the inclusion criteria, excepting those who have indicated that they do not wish to receive research invitations. Information will also be placed in the USAIS waiting room.

An advertisement will be placed on the USAIS website (http://www.AIS.southampton.ac.uk)

from the date of ethical approval to the end of recruitment. A link will be tweeted from @UoS_AIS and @CIRemoteCare once a week from study ethical approval to end of recruitment. Details of the study will be placed on the National Cochlear Implant Users’ Association website.

Patients from other centres may respond to the advertisement; we will obtain participants’ permission to notify individual teams if their patients are involved.

Inclusion criteria

Person using cochlear implant (any device, unilateral or bilateral) for at least 6 months.

Living in the UK.

Aged 18 years or more.

Able to give informed consent.

Sufficient English to understand study documentation and participate in testing.

Access to a computer or device with internet access.

Exclusion criteria

Those that do not fulfil the inclusion criteria plus any medical condition or known disability that would limit their capacity to use the online support tool.

Randomisation

Participants who consent to the study will be allocated to the remote care pathway or the standard care pathway at the baseline visit by the PI using minimisation software.37 Minimisation seeks to achieve a balance across the arms of a trial on one or more predefined patient characteristics.38 39 The minimisation will balance the following factors:

CI user less than a year or more than a year;

Gender;

Distance from the clinic (local or non-local, ie, within 20 miles or more than 20 miles away);

Device (Cochlear or not);

Ability to use Cochlear Remote Assistant Fitting (or not).

The approach will use biased coin minimisation with a base probability of 0.7. Imbalance between the groups will be quantified using the marginal balance method.40

Blinding

It will not be possible to blind participants to which group they are in. Baseline measures will be completed before allocation. Efforts will be made to blind clinicians to which group the participant belongs when they perform exit measures. Where possible, blinded measures will be passed to the University of Nottingham for analysis.

Interventions

Control group: standard clinical care pathway

Participants in the control group will continue with their usual care pathway; they will not have access to remote care. They will be asked to attend twice for this project: baseline and exit measures.

Intervention group: remote care

Those randomised into the treatment group (remote care group) will receive cochlear implant care remotely for 6 months. Clinic appointments will be given if required, and participants must still adhere to any medical check-ups with the cochlear implant surgeon. Participants may access the tools as often as they wish (minimum twice required for project) and can use them wherever they wish (at home, at a friend's house, at the library, etc). Remote care will comprise:

Remote and self-monitoring: Remote care trial participants will access a password-protected online speech recognition test based on the Triple Digit Test (TDT). The site is provided and maintained by Action on Hearing Loss. Participants will listen to sets of three digits in background noise and type in the numbers they hear. Participants will be required to do self-testing at least in months 1 and 6, but can do it at any time during the 6 months. They will be advised that they can do the hearing test using a direct connection from the computer sound card to their speech processor (with the advantage of excluding distracting home environmental noise) or they can listen via speakers (with the advantage of testing their whole hearing system including the microphone). Participants will be encouraged to experiment with different processor settings and programs and redo the test whenever they want. Although the number of times participants take the test will be recorded, the data captured will be qualitative only: participants’ preference and experience of being able to test their hearing at home.

Self-adjustment of device (Remote Assistant Fitting): Only those people using cochlear implants with newer Cochlear devices (CI500 series, CI422 or CI24RE devices using CP800 or CP900 series processors) will be able to participate in the self-adjustment of device; the other manufacturers do not have these tools yet. Participants will use Remote Assistant Fitting to adjust their device programming at any time anywhere. Patients will be required to do self-adjustment at least in months 1 and 6, but can do it at any time during the 6 months.

Those patients in the trial who are eligible for a processor upgrade will receive the upgrade at home rather than coming into the clinic. This will apply to users of all devices.

Online support tool: The research team will design a new online support tool for adults with cochlear implants using LifeGuide.41 LifeGuide is an open source software platform that allows the development and trialling of interactive web-based interventions. This will be an iterative process incorporating feedback from service users at all stages, including focus groups of adults with cochlear implants. The online support tool (Cochlear Implant Remote Care, CIRCA) will incorporate personalised equipment help and information, troubleshooting, rehabilitation, goal setting, help with music and telephone use, and a method of ordering replacement equipment in an easy format to people who may be inexperienced internet users. It will also store the TDT speech recognition test result entered by the participant and provide a comparison with the baseline test and appropriate feedback (no significant change or significantly worse: contact the centre). Participants will be given a unique user name to log in to this support tool; they can access it at any time. They will have the option to include a mobile phone number if they wish to receive reminder text messages for speech processor maintenance and study information.

The participant will enter the following:

Name they would like to be called;

Email address;

Main speech processor;

Month and year of first implant surgery;

Date microphone cover and rechargeable batteries were changed (if appropriate);

Year of birth (optional);

First part of postcode (optional);

Born deaf or lost hearing (optional);

Mobile phone number (optional).

Staff change management assessment

Moving to remote care represents a significant change to cochlear implant centre staff; feedback will be obtained throughout from clinicians using a SharePoint (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA) feedback site, discussions at centre meetings, the project Steering Group and informal discussions. A formal change evaluation will also occur. Interviews will be conducted with 10 members of the multidisciplinary team at 3-month intervals over a period of 6 months (ie, 0, 3, 6 months). Capturing data near the beginning, middle and end of the project will enable us to better capture the ongoing and iterative relationships between perceptions and learning and how these change in response to leadership, social context and decision-making processes over time.42 Interviews will be carried out in the work place or over the phone in accordance with the guidelines and codes of conduct recommended by the British and American Psychological Societies.43 44 Repeated interviews with the same individuals will provide insights into how the nature and content of challenges of telehealth implementation and acceptance are changing and evolving as part of a dynamic process. Examining and understanding staff responses to the change will optimise the chance of the change being sustainable.

The following information will be collected from staff:

Age (in 10-year age bands);

Gender;

Role in team;

Number of years working in cochlear implant centre.

Staff recruitment

Ten staff members who work with adults using cochlear implants at USAIS will be recruited. An email will be sent to all eligible staff enclosing the Staff Participant Information Sheet. This information will also be placed on the staff SharePoint site. Any staff member working at USAIS in a clinical role with adults with implants will be eligible to take part, including staff who support patient equipment needs. A sample size of 10 was chosen in order to provide a variety of differing professions and viewpoints. If more than 10 people want to take part, participants will be selected in order to provide a balance of different clinical roles.

Outcome measures

Baseline measures

All participants will undergo the following baseline measures after signing the consent form:

Speech recognition testing (BKB sentences in quiet and noise and TDT);

PAM;

The Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing (SSQ) questionnaire;

Quality of life questionnaire: Health Utilities Index (HUI) mark 3.

The speech recognition testing is described under the earlier section ‘Standard clinical care pathway’. The PAM is a well-validated generic measure of patient activation that evaluates the knowledge, skills, beliefs and behaviours that patients have for self-management of their long-term condition.45 46 It has been used extensively in over 200 peer-reviewed published studies.47 The SSQ is a 49-item questionnaire measuring self-reported hearing disability over three domains: difficulties understanding speech in different situations, localising and tracking sounds, and ease of listening and naturalness of sound.48 The HUI mark 3 (HUI3) is a multiattribute health status classification system evaluating eight domains of vision, hearing, speech, ambulation, dexterity, emotion, cognition and pain.49

The following information will be collected on the control group and remote care group during the clinical trial:

Number and nature of clinic contacts and visits (including non-attendance);

Repair logs;

Age;

Gender;

Postcode (to calculate distance to clinic)—postcode data will be used once only in order to calculate the distance to the clinic and will then be destroyed;

Cochlear implant device and speech processor;

Highest formal educational qualifications;

Which cochlear implant centre takes care of the participant.

All staff will be reminded to document all contact with patients as usual. Additionally in the remote care group, logs of their interaction with the remote care tools will be stored to assess adherence and utility.

Exit measures (summer 2016)

All participants will undergo the following exit measures:

Speech recognition testing (BKB sentences in quiet and noise and TDT);

PAM;

SSQ questionnaire;

HUI3.

Travel expenses will be paid for baseline and exit measure visits. The day of the exit measures will be considered to be the day the participants exit from the trial.

Participants in the remote care group will be asked to attend a focus group on the day of their exit measures in order to collect qualitative preference and experience data. Focus groups will be audio recorded and transcribed. A small number of participants in the remote care group will be asked if they would be willing to be videoed talking about remote care. These videos will be stored securely on a University of Southampton password-protected network using just the participant's ID. They will be used in presentations to report and promote the research.

Primary outcome measure

Change (from day of entry into study to 6 months after remote care introduced) in patient activation measured using the PAM.

Secondary outcome measures

Stability of hearing measured by change (from day of entry into study to 6 months after remote care introduced) in speech recognition measured using BKB sentences, the TDT, the SSQ questionnaire in the control and treatment arms.

Stability of quality of life measured by change (from day of entry into study to 6 months after remote care introduced) in quality of life measured using the HUI3 in the control and treatment arms.

Patient preference for and experience of remote care in treatment arm reported qualitatively from feedback in online support tool and focus groups.

Clinician preference for and experience of remote care measured qualitatively from three interviews with up to 10 members of clinical staff.

Feasibility outcomes

Recruitment (number of eligible and willing participants);

Attrition (drop-out) and bias;

Adherence to protocol;

Acceptability of randomisation to service users;

Willingness and ability to use remote care tools (hearing test, Remote Assistant Fitting, online support tool).

Hypotheses

Primary

The remote care group will show a greater increase in patient engagement over the 6-month remote care trial period than the control group, measured using the PAM.

Secondary

There will be no more deterioration in hearing in the remote care group compared with the control group, measured using speech recognition (BKB, TDT) and the SSQ questionnaire.

There will be no more deterioration in quality of life in the remote care group compared with the control group, measured using the HUI3.

Service users (patients) will feel positive about remote care, measured qualitatively from feedback in online support tool and in focus groups.

Clinicians will feel positive about remote care, measured qualitatively from interviews with clinical staff.

Data handling

Data will be managed according to the University of Southampton Research Data Management Policy (RDMP). An individual study data management plan is stored on the University network. Stored data will be coded and anonymised, will not include name or address information and will be stored securely: all electronic data will be password protected. Hard copy data will be stored in a locked filing cabinet in a secure office. The University provides secure storage for all active research data (http://library.soton.ac.uk/researchdata/unistorage). The data are regularly backed up and a copy of the backup is regularly off-sited to a secure location for disaster recovery purposes. Research data will be kept for at least 10 years in line with University of Southampton policy.

Metadata records for the data (and published outputs) will also be maintained on the University of Southampton Institutional Research Repository (ePrints). Each deposit can be assigned a unique digital object identifier via the DataCite scheme, allowing it to be cited in publications. No personal data or identifiable data will be included in the data stored in the repository. This will be in accordance with the University's data security policy (http://www.calendar.soton.ac.uk/sectionIV/dppolicy.pdf) and the requirements of the Data Protection Act (1998).

The terms of the PAM licence specify that up to 250 participants can be tested until August 2016. Non-personally identifiable individual data must be shared with Insignia. The data shared shall include individual-level data records containing answers to each of the PAM questions, and if captured (1) demographic variables, health status and condition variables; (2) specific outcome variables including health behaviours, self-management behaviours and whether patients using PAM improved the self-management aspects of their healthcare and (3) the PAM materials’ effect on or relationship to patient healthcare utilisation and costs. Such data shall be reported to Insignia in an electronic format in approximately September 2016.

A data monitoring committee is not required due to the short period of follow-up and minimal project risks.

Trial organisation and monitoring

The trial is led by the PI (HC). Monthly research team meetings will be held. We have formed a Steering Group, with the remit of reflecting on the process and governance of the project including adverse events monitoring. The Steering Group comprises three USAIS clinicians, the USAIS Director, the PI, a consultant on change management (NC) and two service users (patients). It will meet at least three times.

Data analysis plan

To comply with recommendations, analysis will be mainly descriptive.50 Scores on the PAM (primary outcome), quality of life and hearing results will be compared between the two groups (control and remote care group), although statistical analysis of any differences will be interpreted with caution as no formal power calculation was in place, and will primarily be used to estimate effect sizes. Analysis will focus on whether the generic PAM is sensitive enough to show change, or whether a condition-specific empowerment measure needs to be developed. Clinician and participant feedback, use of clinic resources (number and type of appointments) and feasibility outcomes will be reported and analysed qualitatively. IBM SPSS Statistics V.21 will be used.

Public and patient involvement

The research team has a strong commitment to public and patient involvement (PPI); a member of the research team is a service user. This service user was known to the PI to be interested in remote care, and has served on the USAIS Governance Group. The research team contains representatives from the main stakeholders: patient, clinician, cochlear implant company. Two additional service users are on the project Steering Group. Local and national publicity (website, twitter, presentation to National Cochlear Implant Users’ Association, newsletter articles, letters, emails, Yahoo group) have already invited help in designing the research.

Ethics

Participation is entirely voluntary and it has been stressed to patients that if they do not participate, this will not affect their usual clinical care in any way. Written informed consent will be taken from all participants by the PI who has regular Good Clinical Practice (GCP) training. Participants are free to withdraw at any point without giving a reason. A risk analysis has been approved by the University of Southampton.

The PI will inform participants during the trial if any new information comes to light which may affect their willingness to participate.

Confidentiality

Linked anonymity will be used. Participants will be assigned a unique identifier on enrolment. All results will be stored using only this ID. The lookup table will be stored on a password-protected University of Southampton network in a password-protected file separate from the study results, and will be accessible only to the research team.

Adults with cochlear implants are still rare in the general population (∼0.01% of the UK population). BMJ reporting guidelines will be followed: we will not report three or more indirect identifiers (eg, place of treatment, sex, rare disease or treatment, age) for any individuals.51

Dissemination

Research results will be presented locally, nationally and internationally. Dissemination will include but not be limited to peer-reviewed research publications both online and in print, conference and meeting presentations, posters, newsletter articles, website reports, and social media. In order to inform people with cochlear implants of the results, information will be sent to the National Cochlear Implant Users’ Association and other patient groups, and the USAIS patient newsletter. Participants will be offered the opportunity to receive a summary of the findings.

Conclusion

This will be the first RCT of a triple approach to remote care for people using cochlear implants. The study results will inform further work on a larger scale roll out of cochlear implant remote care in the UK.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the people with cochlear implants who give so freely of their time and experience in order to further cochlear implant research. Marta Glowacka and Jin Zhang have provided great expertise in LifeGuide programming. The authors also thank Dean Parker from Action on Hearing Loss for providing the Triple Digit Test interface. They thank Mike Firn from Springfield Consultancy for his support.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Helen Cullington at @CIRemoteCare and Padraig Kitterick at @padraig_hearing

Contributors: HC, PK, LD, MW, NC, EN and LA made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, revised it critically for intellectual content and approved the final manuscript. They agree to be accountable for their work. HC leads the work and takes overall responsibility for the manuscript. PK was involved in all aspects. LD and LA were responsible for the incorporation of the parts of the protocol specific to Cochlear devices; MW worked especially on the LifeGuide parts; EN gave particular input to PPI; NC was responsible for the staff assessment components.

Funding: This work was supported by The Health Foundation Innovating for Improvement Award grant number 1959.

Competing interests: The PI, HC, performs occasional private consultancy work for the cochlear implant company Cochlear Europe. HC reports grants from The Health Foundation, during the conduct of the study; other from Cochlear Europe, other from Advanced Bionics, grants from British Society of Audiology, grants from Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership, other from Cochlear Europe, other from MED-EL, other from Advanced Bionics, grants from Oticon, personal fees from Maney publishers, outside the submitted work. PK reports grants from The Health Foundation during the conduct of this study; grant from Cochlear Europe, grant from Phonak, grant from British Society of Audiology.

Ethics approval: North West—Greater Manchester South Research Ethics Committee (15/NW/0860) and University of Southampton Research Governance Office (ERGO 15329).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data will be managed according to the University of Southampton Research Data Management Policy. Metadata records for the data (and published outputs) will also be maintained on the University of Southampton Institutional Research Repository (ePrints). The ePrints Research Data Repository offers a means for the University's researchers to openly share non-confidential research data, without the need for external data users to undergo any form of authentication. Each deposit is accompanied by appropriate metadata and can be assigned a unique digital object identifier (DOI) via the DataCite scheme, allowing it to be cited in publications. This will be in accordance with the University's data security policy (http://www.calendar.soton.ac.uk/sectionIV/dppolicy.pdf) and the requirements of the Data Protection Act (1998). The terms of the PAM licence specify that up to 250 participants can be tested until August 2016. Non-personally identifiable individual data must be shared with Insignia. The data shared shall include individual-level data records containing answers to each of the PAM questions, and if captured (1) demographic variables, health status and condition variables; (2) specific outcome variables including health behaviours, self-management behaviours and whether patients using PAM improved the self-management aspects of their healthcare; and (3) the PAM materials’ effect on or relationship to patient healthcare utilisation and costs. Such data shall be reported to Insignia in an electronic format in approximately September 2016.

References

- 1.Wilson BS, Dorman MF. Cochlear implants: current designs and future possibilities. J Rehabil Res Dev 2008;45:695–730. 10.1682/JRRD.2007.10.0173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.BCIG. Annual update 2014–2015 2015. http://www.bcig.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/CI-activity-2015.pdf

- 3.Ear Foundation. Cochlear implants. http://www.earfoundation.org.uk/files/download/1221 In: Ear Foundation information sheet, ed., 2016.

- 4.Office for National Statistics. [Archived content] National population projections, 2010-based statistical bulletin. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160105160709/http://ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/npp/national-population-projections/2010-based-projections/index.html 2011.

- 5.Cullington HE. What do our service users really want? [poster]. Ayrshire: British Cochlear Implant Group Annual Conference, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsay IA. Using a patient-driven software tool for programming multiple cochlear implant patients simultaneously in a telemedicine setting [PhD Thesis]. University of Colorado at Denver, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.NHS. Five year forward view. In: NHS, ed., 2014.

- 8.National Information Board. Personalised Health and Care 2020. Work stream 1.1: Enable me to make the right health and care choices: providing patients and the public with digital access to health and care information and transactions. http://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/442834/Work_Stream_1_1.pdf 2015.

- 9.Panagioti M, Richardson G, Small N et al. Self-management support interventions to reduce health care utilisation without compromising outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:356 10.1186/1472-6963-14-356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hibbard JH, Greene J, Shi Y et al. Taking the long view: how well do patient activation scores predict outcomes four years later? Med Care Res Rev 2015;72:324–37. 10.1177/1077558715573871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mosen DM, Schmittdiel J, Hibbard J et al. Is patient activation associated with outcomes of care for adults with chronic conditions? J Ambul Care Manage 2007;30:21–9. 10.1097/00004479-200701000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bench J, Kowal A, Bamford J. The BKB (Bamford-Kowal-Bench) sentence lists for partially-hearing children. Br J Audiol 1979;13:108–12. 10.3109/03005367909078884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes ML, Goehring JL, Baudhuin JL et al. Use of telehealth for research and clinical measures in cochlear implant recipients: a validation study. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2012;55:1112–27. 10.1044/1092-4388(2011/11-0237) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goehring JL, Hughes ML, Baudhuin JL et al. The effect of technology and testing environment on speech perception using telehealth with cochlear implant recipients. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2012;55:1373–86. 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0358) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smits C, Kapteyn TS, Houtgast T. Development and validation of an automatic speech-in-noise screening test by telephone. Int J Audiol 2004;43:15–28. 10.1080/14992020400050004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smits C, Houtgast T. Results from the Dutch speech-in-noise screening test by telephone. Ear Hear 2005;26:89–95. 10.1097/00003446-200502000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smits C, Merkus P, Houtgast T. How we do it: the Dutch functional hearing-screening tests by telephone and internet. Clin Otolaryngol 2006;31:436–40. 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2006.01195.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smits C, Theo Goverts S, Festen JM. The digits-in-noise test: assessing auditory speech recognition abilities in noise. J Acoust Soc Am 2013;133:1693–706. 10.1121/1.4789933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahafzah M. The Triple Digit Test: a self-test of speech perception in cochlear implant users [Thesis (MSc)]. University of Southampton, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aidi T. The Triple Digit Test: A validity and feasibility study [Thesis (MSc)]. University of Southampton, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaandorp MW, Smits C, Merkus P et al. Assessing speech recognition abilities with digits in noise in cochlear implant and hearing aid users. Int J Audiol 2015;54:48–57. 10.3109/14992027.2014.945623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agyemang-Prempeh A. Telemedicine in cochlear implants: a new way of conducting long term patient follow-up [Thesis (MSc)]. University of Southampton, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Action on Hearing Loss. Check your hearing 2015. http://www.actiononhearingloss.org.uk/your-hearing/look-after-your-hearing/check-your-hearing/take-the-check.aspx.

- 24.Vaerenberg B, Smits C, De Ceulaer G et al. Cochlear implant programming: a global survey on the state of the art. Sci World J 2014;2014:501738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eikelboom RH, Jayakody DM, Swanepoel DW et al. Validation of remote mapping of cochlear implants. J Telemed Telecare 2014;20:171–7. 10.1177/1357633X14529234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuzovkov V, Yanov Y, Levin S et al. Remote programming of MED-EL cochlear implants: users’ and professionals’ evaluation of the remote programming experience. Acta Otolaryngol 2014;134:709–16. 10.3109/00016489.2014.892212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McElveen JT Jr, Blackburn EL, Green JD Jr, et al. Remote programming of cochlear implants: a telecommunications model. Otol Neurotol 2010;31:1035–40. 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181d35d87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramos A, Rodriguez C, Martinez-Beneyto P et al. Use of telemedicine in the remote programming of cochlear implants. Acta Otolaryngol 2009;129:533–40. 10.1080/00016480802294369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodríguez C, Ramos A, Falcon JC et al. Use of telemedicine in the remote programming of cochlear implants. Cochlear Implants Int 2010;11(Suppl 1):461–4. 10.1179/146701010X12671177204624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wesarg T, Wasowski A, Skarzynski H et al. Remote fitting in Nucleus cochlear implant recipients. Acta Otolaryngol 2010;130:1379–88. 10.3109/00016489.2010.492480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wasowski A, Skarzynski PH, Lorens A et al. Remote fitting of cochlear implant system. Cochlear Implants Int 2010;11(Suppl 1):489–92. 10.1179/146701010X12671177318105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samuel PA, Goffi-Gomez MV, Bittencourt AG et al. Remote programming of cochlear implants. Codas 2014;26:481–6. 10.1590/2317-1782/20142014007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Botros A, Banna R, Maruthurkkara S. The next generation of Nucleus(®) fitting: a multiplatform approach towards universal cochlear implant management. Int J Audiol 2013;52:485–94. 10.3109/14992027.2013.781277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Müller J, Raine CH. Quality standards for adult cochlear implantation. Cochlear Implants Int 2013;14(Suppl 2):S6–12. 10.1179/1467010013Z.00000000097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu QJ, Galvin J, Wang X et al. Effects of auditory training on adult cochlear implant patients: a preliminary report. Cochlear Implants Int 2004;5(Suppl 1):84–90. 10.1179/cim.2004.5.Supplement-1.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cochlear.com. Nucleus 6 care and maintenance accessed 01/03/2016. http://www.cochlear.com/wps/wcm/connect/us/recipients/nucleus-6/nucleus-6-basics/care-and-maintenance

- 37.Saghaei M, Saghaei S. Implementation of an open-source customizable minimization program for allocation of patients to parallel groups in clinical trials. J Biomed Sci Eng 2011;4:734–9. 10.4236/jbise.2011.411090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taves DR. Minimization: a new method of assigning patients to treatment and control groups. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1974;15:443–53. 10.1002/cpt1974155443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics 1975;31:103–15. 10.2307/2529712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han B, Enas NH, McEntegart D. Randomization by minimization for unbalanced treatment allocation. Stat Med 2009;28:3329–46. 10.1002/sim.3710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yardley L, Osmond A, Hare J et al. Introduction to the LifeGuide: software facilitating the development of interactive behaviour change internet interventions. Edinburgh: The Society for the Study of Artificial Intelligence and Simulation of Behaviour, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pettigrew AM. Context and action in the transformation of the firm. J Manage Stud 1987;24:649–70. 10.1111/j.1467-6486.1987.tb00467.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Pyschological Association. Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct Am Psychol 2002;57:1060–73.12613157 [Google Scholar]

- 44.British Psychological Society. Code of ethics and governance. The Ethics Committee of the British Psychological Society, 2009.

- 45.Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J et al. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res 2005;40(Pt 1):1918–30. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00438.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER et al. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 2004;39(Pt 1):1005–26. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Insignia Health. http://www.insigniahealth.com/products/pam-survey

- 48.Gatehouse S, Noble W. The Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ). Int J Audiol 2004;43:85–99. 10.1080/14992020400050014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feeny D, Furlong W, Boyle M et al. Multi-attribute health status classification systems. Health Utilities Index. Pharmacoeconomics 1995;7:490–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lancaster GA, Dodd S, Williamson PR. Design and analysis of pilot studies: recommendations for good practice. J Eval Clin Pract 2004;10:307–12. 10.1111/j.2002.384.doc.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hrynaszkiewicz I, Norton ML, Vickers AJ et al. Preparing raw clinical data for publication: guidance for journal editors, authors, and peer reviewers. BMJ 2010;340:c181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]